Abstract

Digital technologies ranging from biosensors to virtual reality have revolutionized the healthcare landscape by offering innovations that hold great promise in addressing the challenges posed by rapidly aging populations. To optimize healthcare experiences for older people, it is crucial to understand their user experience (UX) with digital health technologies. This systematic review, covering articles published from 2013 to 2023, aimed to explore frequently used questionnaires for assessing digital healthcare UX among older people. The inclusion criteria were original studies assessing UX in digital health for individuals aged ≥65 years. Of 184 articles identified, 17 were selected after rigorous screening. The questionnaires used included the System Usability Scale (SUS), the User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ), and the Post-Study System Usability Questionnaire. Customized questionnaires based on models such as the Technology Acceptance Model and the Almere model were developed in some studies. Owing to its simplicity and effectiveness in assessing digital health UX among older people, the SUS emerged as the go-to tool (52.9%). Combining the SUS with the UEQ provided comprehensive insights into UX. Specialized questionnaires were also used, but further research is needed to validate and adapt these tools for diverse cultural contexts and evolving technologies.

1. Introduction

The healthcare landscape has undergone a profound transformation with the advent of digital technologies. These advancements encompass a wide spectrum of innovations, including biosensors, wearables [1,2], digital healthcare applications such as health apps [3,4,5,6] and chatbots [7,8], remote clinical management tools [9,10,11,12,13], integrated machine learning algorithms aiding decision-making [14,15], and immersive experiences such as virtual reality [16,17,18,19] and augmented reality [20,21,22]. Moreover, electronic medical records [23,24] and visual analytics/dashboards [25,26,27,28] have become integral components of modern healthcare, forming a digital ecosystem that presents unprecedented opportunities to enhance patient care and monitoring [22]. As far as we know, there is no general system for digital health technology, but it includes the components outlined in Table 1 from our previous research. Amidst the challenges posed by global aging, these digital health solutions hold promise in addressing issues associated with reduced physical and cognitive function, multiple chronic conditions, and shifts in social networks [29]. The application of digital technologies has the potential to not only improve quality of life and well-being, but also foster independent living among older people.

Table 1.

General system components of digital healthcare technologies.

In light of advancements in digital health technologies and demographic shifts, it has become imperative to comprehensively investigate the user experience (UX) of these technological innovations. UX is defined as a “person’s perception and responses resulting from the use and/or anticipated use of a product, system, or service” [30]. UX includes all of the user’s emotions, beliefs, preferences, perceptions, physical and psychological responses, behaviors, and accomplishments that occur before, during, and after use. Usability, when interpreted from the perspective of the user’s personal goals, can include the kind of perceptual and emotional aspects typically associated with UX [30]. The UX investigation of digital health technologies is a crucial step toward understanding specific needs, such as those of older people, and achieving optimal healthcare experiences.

Various methods have been used to investigate the UX of digital health technologies, encompassing questionnaires, interviews, and observations [31]. The focus of this systematic review is on questionnaires as a method for investigating the UX of digital health technologies among older people. Questionnaires provide structured and quantifiable data which can help gather a comprehensive overview of the experiences of older people with digital health technologies. Moreover, validity and reliability are crucial factors in ensuring the scientific rigor of such investigations. Original questionnaires are vital when evaluating specific aspects of digital health technologies [32]. Consequently, both standardized and custom-designed questionnaires tailored to the nuances of digital health technologies play a crucial role in uncovering the UX of older people.

Given this background, the present study aimed to review and introduce the questionnaires frequently used to assess the UX of older people when using digital healthcare technologies and to explore the contents of original or customized questionnaires. The outcomes of this study are expected to provide guidance for designing and implementing future research endeavors. Moreover, these findings are anticipated to be useful for people in the industry to assess the UX of older people. This, in turn, will significantly contribute to the development of user-centric healthcare technologies.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodology employed in this systematic review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [33]. This systematic review has been registered in the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (registration number: CRD42023418271). This systematic review of the literature was conducted in April 2023, utilizing data from PubMed, Google Scholar, and the Ichushi Web of Japanese journal databases. To ensure the inclusion of the latest evidence in the field, the present review analyzed manuscripts and articles published from 1 January 2013 to 31 March 2023. The selection of this time period was based on the progress and innovation observed in the field of digital health technology, as well as the corresponding brush-up on UX research methods. In formulating the inclusion criteria, the PICOS (P = population, I = interventions, C = comparator, O = outcome, S = study design) format was adopted.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) original research papers that utilized questionnaires to assess the UX of digital health technologies among older people; (2) papers describing the content of original or customized questionnaires used for UX evaluation; (3) papers with main targets aged ≥65 years. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) review articles, protocols, conference papers, and reports; (2) papers lacking full-text availability; (3) papers that employed interviews for UX assessment; and (4) papers that assessed the UX of technologies related to specific diseases, such as cancer, surgical and radiological technologies, and oral hygiene. The targeted population for this review had no specific income-based restrictions.

The search strategy employed four categories of keywords (Table 2), with the keywords within each category combined using the “OR” Boolean operator. Subsequently, to retrieve relevant papers, the results of these searches were combined using the “AND” Boolean operator. The search was limited to the Title/Abstract search field and filtered for articles available only in English or Japanese.

Table 2.

Keywords used for the search strategy.

Following the initial search, a total of 174 articles were identified from PubMed, with an additional 6 from Google Scholar and 4 from Ichushi Web. These findings underwent analysis and screening conducted by three experts from the research team, consisting of a rehabilitation medicine researcher and two engineering researchers. This collaborative effort allowed us to consider both geriatric and technical perspectives. The initial screening was based on the titles and abstracts of the identified articles. Subsequently, the same experts evaluated the full text of selected papers. In the case of conflicting opinions, consensus was reached through discussion among the three experts. Finally, a list of included papers was compiled.

Data extraction involved collecting the following information from included papers: the first author’s name, year of publication, evaluation questionnaire, details of the original or customized questionnaire employed, and the digital health technology under assessment. The collected data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, including frequency and frequency percentages. Additionally, an investigation was conducted to determine whether the reliability and validity of the extracted questionnaires had been verified, whether manuals for these questionnaires were available, and whether benchmarks had been established.

3. Results

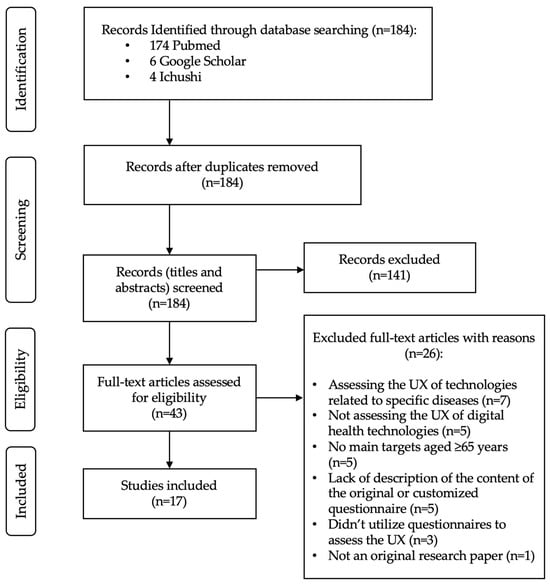

The comprehensive search of the PubMed, Google Scholar, and Ichushi Web databases initially yielded 184 papers. A thorough screening of the titles and abstracts led to the exclusion of 141 papers. Subsequently, the full texts of the remaining 43 papers underwent meticulous review. In the final analysis, 17 papers were considered suitable for data extraction [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of search strategy.

The System Usability Scale (SUS) emerged as the most frequently used standardized questionnaire for assessing digital health technologies among older people (n = 9, 52.9%) [35,38,39,42,44,45,48,49,50]. Other commonly utilized questionnaires included the User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ) and its short version (n = 5, 29.4%) [35,37,42,44,45], the Post-Study System Usability Questionnaire (PSSUQ; n = 2, 11.8%) [34,42], the Quebec User Evaluation of Satisfaction with Assistive Technology (QUEST; n = 2, 11.8%) [46,48], the Facilitators and Barriers Survey/Mobility (FABS/M; n = 1, 5.9%) [46], the Psychosocial Impact of Assistive Devices Scale (PIADS; n = 1, 5.9%) [46], the Telehealth Satisfaction Questionnaire for Wearable Technology (TSQ-WT; n = 1, 5.9%) [47], and the User Satisfaction Evaluation Questionnaire (USEQ; n = 1, 5.9%) [38]. Eight studies utilized multiple standardized questionnaires [35,38,39,42,44,45,46,48] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Descriptive analyses of the 17 papers included in the present review.

Table 4 describes the standardized questionnaires used to assess the UX of digital health technologies among older people and provides information on their reliability and validity, the presence of manuals, and benchmarks.

Table 4.

The standardized questionnaires used to assess the user experience of digital health technologies among older people.

Among the seventeen studies identified, seven utilized original or customized questionnaires [36,38,40,41,43,44,45], of which four relied exclusively on customized questionnaires. [6,10,11,13]. Of the six original or customized questionnaires, four were developed based on the Technology Acceptance Model (TMT) [38,43,44,45], one was created incorporating elements of both the TMT and the Almere model [40], another was derived from the Tilburg Frailty Indicator (TFI) [36], and one was created using relevant literature related to healthcare services, mobile services, and information communication services [41] (Table 3).

4. Discussion

According to the findings of this review, the SUS emerged as the most used standardized questionnaire to assess the UX of digital health technologies among older people, and it was used without modifications in its standard form. Despite being a self-described “quick and dirty” usability scale, the SUS has garnered widespread popularity in usability assessments [51,68,69]. It comprises 10 items, each offering five scale steps, and includes relevant questions that produce findings useful in understanding UX, with odd-numbered items conveying a positive tone and even-numbered items expressing a negative tone. Participants are instructed to complete the SUS immediately after interacting with the digital health technologies, recording their prompt responses to each item. The SUS generates an overall score range from 0 to 100 in 2.5-point increments, and online tools for calculating SUS scores are freely available. No license fee is required for using the SUS; the only prerequisite is acknowledgment of the source. Various translations of the SUS exist, but only a few have undergone psychometric evaluation [70]. Recent studies have consistently demonstrated high reliability for the SUS (approximately 0.90) and established its validity and sensitivity in discerning usability disparities, interface types, task accomplishment, UX, and business success indicators [53]. Furthermore, its concise 10-item format makes it user-friendly, especially for older people. Additionally, the global average score for overall SUS is 68.0 ± 12.5 [53]. The grading scale is as follows: F, SUS score < 60; D, 60 ≤ score < 70; C, 70 ≤ score < 80; B, 80 ≤ score < 90; A, score ≥ 90 [52]. This grading scale is structured in a way that considers a SUS score of 68 as the center of the range for the ‘C’, such as grading on a curve. Furthermore, the high correlation between the SUS and the UEQ (r between 0.60 and 0.82, p < 0.0001) [57] could further emphasize its potential as a standard tool for evaluating usability and UX in digital healthcare technologies for older people.

The UEQ was the second most frequently employed standardized questionnaire. Furthermore, the UEQ was utilized in conjunction with the SUS in four of the five studies it was employed in [35,42,44,45]. The UEQ and SUS serve similar purposes in assessing the UX and usability of digital products, but have some differences and unique advantages. The UEQ includes six aspects—attractiveness, perspicuity, efficiency, dependability, stimulation, and novelty [54]—and offers a more comprehensive and detailed assessment of UX, including emotional and experiential aspects. On the other hand, the SUS is a simple and effective tool for assessing overall usability [51,68,69]. It focuses on the usability aspect of UX, providing a single score that indicates overall usability [51]. Bergquist et al. [35] assessed the usability of three smartphone app-based self-tests of physical function in home-based settings using the SUS and UEQ, and reported that the participants experienced high levels of perceived ease of use when using the apps. Macis et al. [45] employed the SUS and UEQ to assess the usability and UX of a novel mobile system to prevent disability; in particular, the UEQ was included as an evaluation tool to complement the domains addressed by the SUS. Thus, combining both the UEQ and SUS might provide a more holistic understanding of UX.

The following additional questionnaires were also used: PSSUQ, QUEST, FABS/M, PIADS, TSQ-WT, and USEQ. Only TSQ-WT was used individually. The PSSUQ focuses on assessing system usability and measures factors such as system performance, reliability, and overall satisfaction [58,59]. The QUEST evaluates user satisfaction with assistive technology specifically and considers factors such as the device’s effectiveness, ease of use, and impact on daily life [60]. The FABS/M is designed to assess mobility-related assistive devices and examines the facilitators and barriers that users encounter when using these devices [61]. The PIADS measures the psychosocial impact of assistive devices, focusing on how these devices affect users’ self-esteem, well-being, and participation in daily activities [63]. The TSQ-WT is tailored for assessing user satisfaction with wearable telehealth technologies, considering factors such as ease of use and satisfaction with remote health monitoring [66]. The USEQ is a general questionnaire for evaluating user satisfaction without focusing on specific domains [67]. These questionnaires are specialized for different purposes, such as system usability, assistive technology, mobility devices, psychosocial impact, telehealth, and overall user satisfaction. Researchers choose the more relevant ones based on study objectives and the technology being assessed.

The findings of this review indicate that six customized questionnaires have been developed based on the TMT, Almere model, and TFI. The TAM, initially formulated by Davis in 1989 [71], is a widely recognized theoretical framework in the field of technology adoption and user acceptance. It aims to clarify the factors that influence an individual’s decision to accept and use a new technology or information system. Its core components are perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use, and these factors directly influence a user’s intention to use technology, which in turn affects their actual usage behavior [71]. It has been used as a basis for developing questionnaires to assess user perceptions of new technologies [38,40,43,44,45]. These questionnaires, which aim to measure perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use, help predict whether users will adopt a technology.

On the other hand, the Almere model functions as a conceptual framework in the field of UX design and research. It is designed to provide a structured approach to understanding and enhancing the UX of digital products and services, especially concerning users’ acceptance of socially assistive robots [72]. It encompasses 12 constructs, as stated in the introduction part [72]. The present review reveals that the Almere model has been used to measure attitudes toward robot assistance in regard to activities of daily living among older people living independently [40].

The TFI is an instrument used to quantify the frailty of older adults from their own perspective across three domains: physical, psychological, and social [73]. Borda et al. [36] employed the TFI to gain insights into health self-management requirements, frailty, age-related changes, and the health information support provided by consumer wearable devices, particularly among older adults living independently.

Additionally, Lee et al. [41] adapted the survey questionnaire items from relevant literature on healthcare, mobile, and information communication services to explain the intentions of consumers regarding the use of mHealth applications. This comprehensive assessment encompassed seven key constructs, each measured with multiple items. The scale items for health stress and the epistemic value as contextual personal values were adapted from Sheth et al. [74], while the measurement items for emotion (enjoyment) and intention to adopt were developed based on the work of Davis et al. [71]. In addition, the items measuring reassurance were taken from O’Keefe and Sulanowski [75] and modified for the study. The convenience value was borrowed from Berry et al. [76] and developed in the study. Finally, the measurement items for the usefulness value were developed with reference to Davis’s items [71]. All of the measurement items were modified to emphasize health-related events and behaviors based on personal values with respect to mHealth [77,78]. They also included the contents of mHealth services. Each item was measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree”.

Customized questionnaires have been developed based on the theoretical frameworks of the TMT, Almere model, and TFI. These frameworks primarily focus on understanding the acceptability of digital technology rather than the user experience. This distinction is crucial because acceptability assessments primarily investigate factors influencing the decision to adopt and use technology, such as perceived usefulness and ease of use, which are essential for technology adoption. On the other hand, user experience assessments delve deeper into the subjective aspects of interaction with technology, including emotional responses, satisfaction, and usability. Seknoh et al. (2022) reported that they developed a generic theoretical framework of acceptability questionnaires that can be adapted to assess the acceptability of any healthcare intervention [79]. Assessing acceptability might help identify characteristics of interventions that may be improved.

In conclusion, this systematic review highlights the prevalent use of standardized questionnaires for evaluating the UX of digital health technologies among older people. In these questionnaires, the SUS emerged as the most frequently employed tool, underscoring its popularity and effectiveness in assessing usability. Its simplicity, wide applicability, and availability of benchmarks make it a valuable choice for evaluating digital healthcare technologies. Additionally, the high correlation observed between the SUS and UEQ suggests their complementary use for a comprehensive understanding of UX. Furthermore, several other specialized questionnaires were utilized, each tailored to assess specific aspects of usability and user satisfaction, including user acceptability as a main focus based on theoretical frameworks. These tailored approaches emphasize the importance of aligning UX assessment with theoretical frameworks and considering user acceptability, providing a holistic approach to evaluating digital health technologies for older people.

This study has several limitations. First, the scope of this review was limited to studies published in English or Japanese, potentially excluding valuable research conducted in other languages. Moreover, the exclusion of papers lacking a full text and those employing interviews for UX assessment might have led to the omission of relevant studies. Second, the focus on older people might limit the generalizability of the findings to younger populations. Third, the evolving landscape of digital health technologies necessitates continued research and updates to encompass the latest developments. Finally, the psychometric properties of some questionnaires and their applicability to diverse cultural contexts require further investigation to enhance their validity and reliability in assessing UX among older people.

Author Contributions

E.T. designed this study, conducted the data collection, and drafted the manuscript. H.M. performed the data analysis and provided critical revisions to the manuscript. T.T., K.N. and K.M. assisted in the data collection, conducted the literature review, and contributed to the manuscript editing. Y.M., T.F. and I.K. provided expertise in digital health technologies and reviewed and edited the manuscript for subject-specific content. Y.I. reviewed and critiqued the manuscript, provided valuable intellectual input, and supervised the project. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is based on data collected for a project funded by the “Knowledge Hub Aichi”, Priority Research Project IV from the Aichi Prefectural Government in September 2022.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kim, J.; Campbell, A.S.; de Ávila, B.E.; Wang, J. Wearable biosensors for healthcare monitoring. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Badea, M.; Tiwari, S.; Marty, J.L. Wearable Biosensors: An Alternative and Practical Approach in Healthcare and Disease Monitoring. Molecules 2021, 26, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almalki, M.; Giannicchi, A. Health Apps for Combating COVID-19: Descriptive Review and Taxonomy. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2021, 9, e24322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connolly, S.L.; Kuhn, E.; Possemato, K.; Torous, J. Digital Clinics and Mobile Technology Implementation for Mental Health Care. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2021, 23, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Singh, R.P.; Suman, R. Telemedicine for healthcare: Capabilities, features, barriers, and applications. Sens. Int. 2021, 2, 100117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKay, F.H.; Cheng, C.; Wright, A.; Shill, J.; Stephens, H.; Uccellini, M. Evaluating mobile phone applications for health behaviour change: A systematic review. J. Telemed. Telecare 2018, 24, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, F.; Potts, C.; Bond, R.; Mulvenna, M.; Kostenius, C.; Dhanapala, I.; Vakaloudis, A.; Cahill, B.; Kuosmanen, L.; Ennis, E. A Mental Health and Well-Being Chatbot: User Event Log Analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2023, 11, e43052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudor Car, L.; Dhinagaran, D.A.; Kyaw, B.M.; Kowatsch, T.; Joty, S.; Theng, Y.L.; Atun, R. Conversational Agents in Health Care: Scoping Review and Conceptual Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e17158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, H.S.; Sharma, S.; Verma, S. Smartphone app in self-management of chronic low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. Spine J. 2018, 27, 2862–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Stengel, S.; Szecsenyi, J.; Peters-Klimm, F. Health care professionals’ perspectives on the utilisation of a remote surveillance and care tool for patients with COVID-19 in general practice: A qualitative study. BMC Prim. Care 2022, 23, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omboni, S.; Caserini, M.; Coronetti, C. Telemedicine and M-Health in Hypertension Management: Technologies, Applications and Clinical Evidence. High Blood Press. Cardiovasc. Prev. 2016, 23, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens, A.P.; Krebs, C.; Kuruppu, S.; Brem, A.K.; Kowatsch, T.; Aarsland, D.; Klöppel, S. Broadened assessments, health education and cognitive aids in the remote memory clinic. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1033515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trenfield, S.J.; Awad, A.; McCoubrey, L.E.; Elbadawi, M.; Goyanes, A.; Gaisford, S.; Basit, A.W. Advancing pharmacy and healthcare with virtual digital technologies. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2022, 182, 114098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Martinez, S.; Camara, O.; Piella, G.; Cikes, M.; González-Ballester, M.; Miron, M.; Vellido, A.; Gómez, E.; Fraser, A.G.; Bijnens, B. Machine Learning for Clinical Decision-Making: Challenges and Opportunities in Cardiovascular Imaging. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 765693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tack, C. Artificial intelligence and machine learning | applications in musculoskeletal physiotherapy. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 2019, 39, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Zhao, X.; Guan, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, K. The effect of virtual reality technology on anti-fall ability and bone mineral density of the elderly with osteoporosis in an elderly care institution. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2023, 28, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quay, C.; Ramakrishnan, A. Innovative Use of Virtual Reality to Facilitate Empathy Toward Older Adults in Nursing Education. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2023, 44, 300–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.B. In older adults with frailty, virtual reality exercise training improves walking speed and balance. Ann. Intern. Med. 2023, 176, Jc106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Lin, C.H.; Wu, W.R.; Chiu, H.Y.; Huang, H.C. Virtual reality exercise programs ameliorate frailty and fall risks in older adults: A meta-analysis. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2023, 71, 2946–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, A. Microsoft HoloLens 2 in Medical and Healthcare Context: State of the Art and Future Prospects. Sensors 2022, 22, 7709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piatkowski, M.; Taylor, E.; Wong, B.; Taylor, D.; Foreman, K.B.; Merryweather, A. Designing a Patient Room as a Fall Protection Strategy: The Perspectives of Healthcare Design Experts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bond, R.; Peace, A. Towards a digital health future. Eur. Heart J. Digit. Health 2021, 2, 60–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janett, R.S.; Yeracaris, P.P. Electronic Medical Records in the American Health System: Challenges and lessons learned. Cien. Saude Colet. 2020, 25, 1293–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kataria, S.; Ravindran, V. Electronic health records: A critical appraisal of strengths and limitations. J. R. Coll. Physicians Edinb. 2020, 50, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caban, J.J.; Gotz, D. Visual analytics in healthcare—Opportunities and research challenges. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2015, 22, 260–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, L.; Sikora, A. Clinician-Designed Dashboards. Hosp. Pharm. 2023, 58, 225–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siette, J.; Dodds, L.; Sharifi, F.; Nguyen, A.; Baysari, M.; Seaman, K.; Raban, M.; Wabe, N.; Westbrook, J. Usability and Acceptability of Clinical Dashboards in Aged Care: Systematic Review. JMIR Aging 2023, 6, e42274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpao, A.F.; Ahumada, L.M.; Gálvez, J.A.; Rehman, M.A. A review of analytics and clinical informatics in health care. J. Med. Syst. 2014, 38, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharani, A.; Pendleton, N.; Leroi, I. Hearing impairment, loneliness, social isolation, and cognitive function: Longitudinal analysis using English Longitudinal Study on Ageing. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2019, 27, 1348–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 9241-210:2010(en); Ergonomics of Human-System Interaction—Part 210: Human-Centred Design for Interactive Systems. Online Browsing Platform (OBP): London, UK, 2010. Available online: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:9241:-210:ed-1:v1:en (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Maqbool, B.; Herold, S. Potential effectiveness and efficiency issues in usability evaluation within digital health: A systematic literature review. J. Syst. Softw. 2024, 208, 111881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, H. Validity and reliability in qualitative research. Curationis 1993, 16, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Int. J. Surg. 2010, 8, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakogiannis, C.; Tsarouchas, A.; Mouselimis, D.; Lazaridis, C.; Theofillogianakos, E.K.; Billis, A.; Tzikas, S.; Fragakis, N.; Bamidis, P.D.; Papadopoulos, C.E.; et al. A patient-oriented app (ThessHF) to improve self-care quality in heart failure: From evidence-based design to pilot study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2021, 9, e24271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergquist, R.; Vereijken, B.; Mellone, S.; Corzani, M.; Helbostad, J.L.; Taraldsen, K. App-based self-administrable clinical tests of physical function: Development and usability study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020, 8, e16507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borda, A.; Gilbert, C.; Gray, K.; Prabhu, D. Consumer wearable information and health self management by older adults. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2018, 246, 42–61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Tang, Q.; Xu, S.; Leng, P.; Pan, Z. Design and evaluation of an augmented reality-based exergame system to reduce fall risk in the elderly. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingos, C.; Costa, P.; Santos, N.C.; Pêgo, J.M. Usability, acceptability, and satisfaction of a wearable activity tracker in older adults: Observational study in a real-life context in northern Portugal. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e26652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J.; Murphy, E.; Gavin, S.; Pascale, A.; Deparis, S.; Tommasi, P.; Smith, S.; Hannigan, C.; Sillevis Smitt, M.; van Leeuwen, C.; et al. A digital platform to support self-management of multiple chronic conditions (ProACT): Findings in relation to engagement during a one-year proof-of-concept trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e22672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Huang, C. Attitudes of the elderly living independently towards the use of robots to assist with activities of daily living. Work 2021, 69, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Han, S.; Jo, S.H. Consumer choice of on-demand mHealth app services: Context and contents values using structural equation modeling. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2017, 97, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macis, S.; Loi, D.; Ulgheri, A.; Pani, D.; Solinas, G.; Manna, S.; Cestone, V.; Guerri, D.; Raffo, L. Design and usability assessment of a multi-device SOA-based telecare framework for the elderly. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2020, 24, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyle, W.; Pu, L.; Murfield, J.; Sung, B.; Sriram, D.; Liddle, J.; Estai, M.; Lion, K. Consumer and provider perspectives on technologies used within aged care: An Australian qualitative needs assessment survey. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2022, 41, 2557–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Rodríguez, R.; Moreno-Sánchez, P.A.; Valdés-Aragonés, M.; Oviedo-Briones, M.; Divan, S.; García-Grossocordón, N.; Rodríguez-Mañas, L. FriWalk robotic walker: Usability, acceptance and UX evaluation after a pilot study in a real environment. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2020, 15, 718–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Rodríguez, R.; Villalba-Mora, E.; Valdés-Aragonés, M.; Ferre, X.; Moral, C.; Mas-Romero, M.; Abizanda-Soler, P.; Rodríguez-Mañas, L. Usability, user experience, and acceptance evaluation of CAPACITY: A technological ecosystem for remote follow-up of frailty. Sensors 2021, 21, 6458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salatino, C.; Andrich, R.; Converti, R.M.; Saruggia, M. An observational study of powered wheelchair provision in Italy. Assist. Technol. 2016, 28, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, L.I.; Jansen, C.P.; Depenbusch, J.; Gabrian, M.; Sieverding, M.; Wahl, H.W. Using wearables to promote physical activity in old age: Feasibility, benefits, and user friendliness. Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2022, 55, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stara, V.; Harte, R.; Di Rosa, M.; Glynn, L.; Casey, M.; Hayes, P.; Rossi, L.; Mirelman, A.; Baker, P.M.A.; Quinlan, L.R.; et al. Does culture affect usability? A trans-European usability and user experience assessment of a falls-risk connected health system following a user-centred design methodology carried out in a single European country. Maturitas 2018, 114, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Aldunate, R.G.; Paramathayalan, V.R.; Ratnam, R.; Jain, S.; Morrow, D.G.; Sosnoff, J.J. Preliminary evaluation of a self-guided fall risk assessment tool for older adults. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2019, 82, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Velsen, L.; Frazer, S.; N’Dja, A.; Ammour, N.; Del Signore, S.; Zia, G.; Hermens, H. The reliability of using tablet technology for screening the health of older adults. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2018, 247, 651–655. [Google Scholar]

- Brooke, J. SUS: A quick and dirty usability scale. In Usability Evaluation in Industry; Jordan, P.W., Ed.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 1996; pp. 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Bangor, A.; Kortum, P.; Miller, J. Determining what individual SUS scores mean: Adding an adjective rating scale. J. Usability Stud. 2009, 4, 114–123. [Google Scholar]

- Bangor, A.; Kortum, P.T.; Miller, J.T. An empirical evaluation of the system usability scale. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Int. 2008, 24, 574–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laugwitz, B.; Held, T.; Schrepp, M. Construction and evaluation of a user experience questionnaire. In Proceedings of the Symposium of the Workgroup Human-Computer Interaction and Usability Engineering of the Austrian Computer Society, Graz, Austria, 20–21 November 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schrepp, M. User Experience Questionnaire Handbook; User Experience Questionnaire: Weyhe, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadros, J.; Serrano, V.; García-Zubía, J.; Hernandez-Jayo, U. Design and evaluation of a user experience questionnaire for remote labs. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 50222–50230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Kortum, P.; Oswald, F. Psychometric evaluation of the USE (usefulness, satisfaction, and ease of use) questionnaire for reliability and validity. Hum. Fac. Erg. Soc. Ann. 2018, 62, 1414–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.R. Psychometric evaluation of the Post-Study System Usability Questionnaire: The PSSUQ. Hum. Fac. Erg. Soc. Ann. 1992, 2, 1259–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.R. Psychometric evaluation of the PSSUQ using data from five years of usability studies. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Int. 2002, 14, 463–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demers, L.; Weiss-Lambrou, R.; Ska, B. The Quebec User Evaluation of Satisfaction with Assistive Technology (QUEST 2.0): An overview and recent progress. Technol. Disabil. 2002, 14, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, D.B.; Hollingsworth, H.H.; Stark, S.; Morgan, K.A. A subjective measure of environmental facilitators and barriers to participation for people with mobility limitations. Disabil. Rehabil. 2008, 30, 434–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, D.B.; Hollingsworth, H.H.; Stark, S.L.; Morgan, K.A. Participation survey/mobility: Psychometric properties of a measure of participation for people with mobility impairments and limitations. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2006, 87, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jutai, J.; Day, H. Psychosocial Impact of Assistive Devices Scale (PIADS). Technol. Disabil. 2002, 14, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, H.; Jutai, J. Measuring the psychosocial impact of assistive devices: The PIADS. Can. J. Rehabil. 1996, 9, 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Day, H.; Jutai, J.; Campbell, K.A. Development of a scale to measure the psychosocial impact of assistive devices: Lessons learned and the road ahead. Disabil. Rehabil. 2002, 24, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiari, L.; Van Lummel, R.; Becker, C.; Pfeiffer, K.; Lindemann, U.; Zijlstra, W. Classification of the user’s needs, characteristics and scenarios—Update. In Report from the EU Project (6th Framework Program, IST Contract No. 045622) Sensing and Action to Support Mobility in Ambient Assisted Living; Crown Copyright: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Gómez, J.A.; Manzano-Hernández, P.; Albiol-Pérez, S.; Aula-Valero, C.; Gil-Gómez, H.; Lozano-Quilis, J.A. USEQ: A short questionnaire for satisfaction evaluation of virtual rehabilitation systems. Sensors 2017, 17, 1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooke, J. SUS: A retrospective. J. Usability Stud. 2013, 8, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Zviran, M.; Glezer, C.; Avni, I. User satisfaction from commercial web sites: The effect of design and use. Inform. Manag. 2006, 43, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blažica, B.; Lewis, J.R. A Slovene translation of the system usability scale: The SUS-SI. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Int. 2015, 31, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quart. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerink, M.; Kröse, B.; Evers, V.; Wielinga, B. Assessing acceptance of assistive social agent technology by older adults: The Almere model. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2010, 2, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbens, R.; Assen, M.; Luijkx, K.; Wijnen-Sponselee, M.; Schols, J.M.G.A. The Tilburg Frailty Indicator: Psychometric properties. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2010, 11, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Newman, B.I.; Gross, B.L. Why we buy what we buy: A theory of consumption values. J. Bus. Res. 1991, 22, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, G.J.; Sulanowski, B.K. More than just talk: Uses, gratifications, and the telephone. J. Mass Commun. Q. 1995, 72, 922–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, L.L.; Seiders, K.; Grewal, D. Understanding service convenience. J. Mark. 2002, 66, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Han, S.; Chung, Y. Internet use of consumers aged 40 and over: Factors that influence full adoption. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2014, 42, 1563–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Han, S. Determinants of adoption of mobile health services. Online Inform. Rev. 2015, 39, 556–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhon, M.; Cartwright, M.; Francis, J.J. Development of a theory-informed questionnaire to assess the acceptability of healthcare interventions. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).