Complexation of Terpenes for the Production of New Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Molecules and Their Encapsulation in Order to Improve Their Activities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Healthcare-Associated Infections Related to Adherent Bacteria and Their Biofilms

3. Food Poisoning Related to Adherent Bacteria and Their Biofilms

4. Biofilm

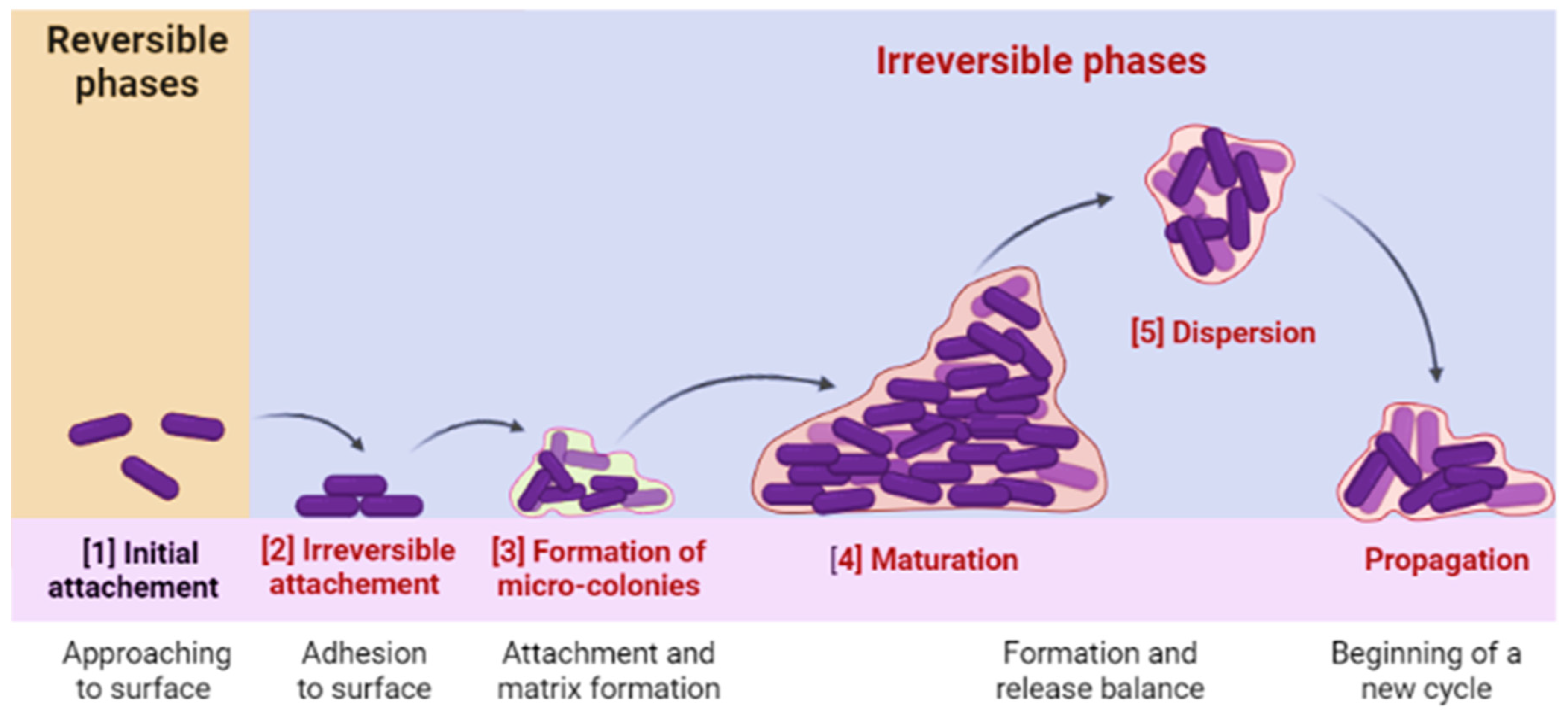

4.1. Biofilm Formation

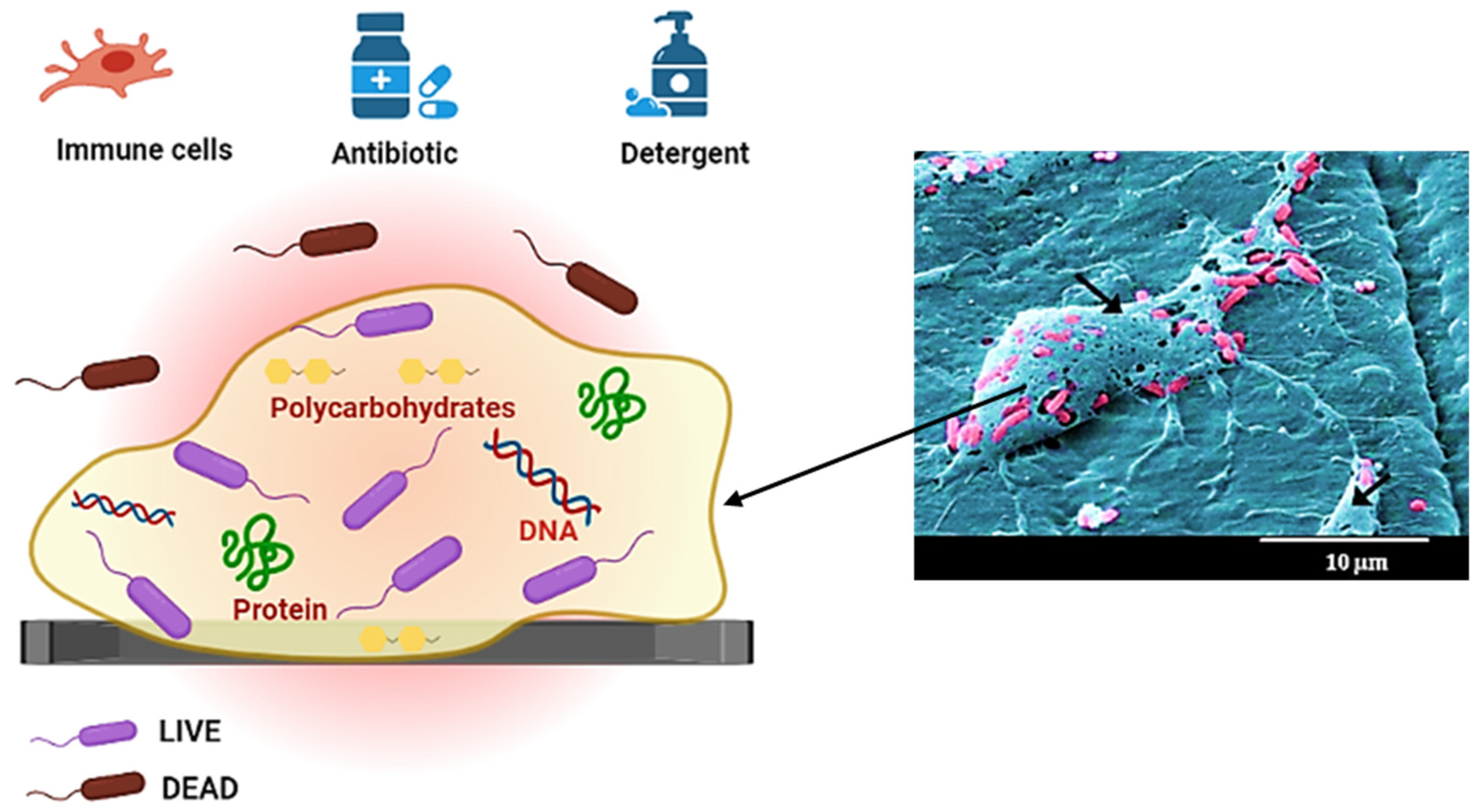

4.2. Biofilm Matrix

5. Terpenes and Their Derivatives as Good Candidates to Fight against Adherent Bacterial Cells and Biofilm (Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Effect)

| Terpene Derivative | Structure | Bacteria | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limonene |  | Staphylococcus aureus | [187] |

| Escherichia coli | [188] | ||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa Staphylococcus aureus | [189] | ||

| Enterococcus faecalis | [190] | ||

| Escherichia coli Staphylococcus aureus Enteroccocus faecalis Listeria monocytogenes | [21] | ||

| Myrcene |  | Escherichia coli Salmonella enterica Staphylococcus aureus | [191] |

| α-Pinene |  | Staphylococcus aureus Escherichia coli | [192] |

| Borneol |  | Staphylococcus aureus Escherichia coli Pseudomonas aeruginosa | [193] |

| Menthol |  | Escherichia coli Pseudomonas aeruginosa Klebsiella pneumonia Staphylococcus aureus | [194] |

| Escherichia coli Staphylococcus aureus Listeria innocua, Saccharomyces cervicea | [195] | ||

| Thymol |  | Enterobacter sakazakii | [196] |

| Salmonella Enteritidis | [10] | ||

| Aeromonas hydrophila | [197] | ||

| Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | [198] | ||

| Carvacrol |  | Escherichia coli Pseudomonas aeruginosa Salmonella spp. | [199] |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa Enterococcus faecalis | [200] | ||

| Eugenol |  | Listeria monocytogenes CECT 933 Escherichia coli ATCC 35218 Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538 | [201] |

| Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 Escherichia coli Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 9027 Pseudomonas aeruginosa Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 Staphylococcus aureus Streptococcus mutans ATCC 0446 | [202] |

6. Metal Complexes Based on Terpene Ligands and Their Biological Activities

6.1. The Reactivity of Terpenes

6.2. Oligodynamic Effect

6.3. Antimicrobial Activity of Metal Complexes Based on Terpene Ligands

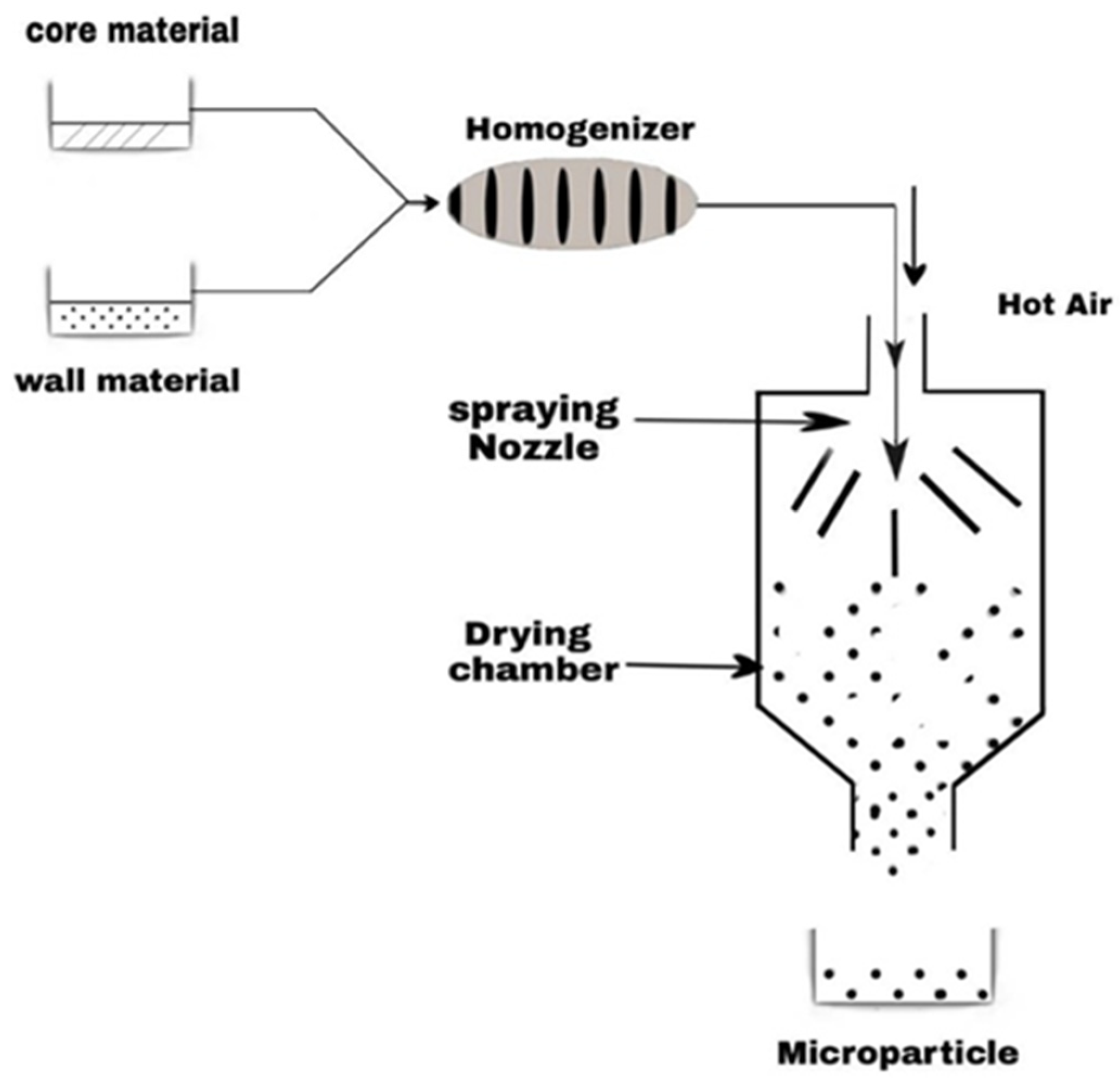

7. Encapsulation of Terpene Derivatives to Improve Their Stability and Antimicrobial Activity

8. Conclusions

9. Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Russotto, V.; Cortegiani, A.; Raineri, S.M.; Giarratano, A. Bacterial contamination of inanimate surfaces and equipment in the intensive care unit. J. Intensive Care 2015, 3, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, S.; Heyndrickx, M.; Vackier, T.; Steenackers, H.; Verplaetse, A.; Reu, K.D. Identification and Spoilage Potential of the Remaining Dominant Microbiota on Food Contact Surfaces after Cleaning and Disinfection in Different Food Industries. J. Food Prot. 2019, 82, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripolles-Avila, C.; Ríos-Castillo, A.G.; Rodríguez-Jerez, J.J. Development of a peroxide biodetector for a direct detection of biofilms produced by catalase-positive bacteria on food-contact surfaces. CyTA J. Food 2018, 16, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-Y.; Dickter, J.K. Nosocomial Infections: A History of Hospital-Acquired Infections. Gastrointest. Endosc. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 30, 637–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haque, M.; Sartelli, M.; McKimm, J.; Abu Bakar, M. Health care-associated infections—An overview. Infect. Drug Resist. 2018, 11, 2321–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyepong, N.; Govinden, U.; Owusu-Ofori, A.; Essack, S.Y. Multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections in a teaching hospital in Ghana. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2018, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, A.; Assadian, O. Survival of Microorganisms on Inanimate Surfaces. In Use of Biocidal Surfaces for Reduction of Healthcare Acquired Infections; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Healthcare-Associated Infections. Data Portal. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hai/data/portal/index.html (accessed on 7 November 2022).

- Khatun, M.F.; Khan, M.A.S.; Ahmed, M.F.; Rahman, M.M.; Rahman, S.R. Assessment of foodborne transmission of Salmonella enteritidis in hens and eggs in Bangladesh. Vet. Med. Sci. 2022, 8, 2032–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yammine, J.; Gharsallaoui, A.; Fadel, A.; Mechmechani, S.; Karam, L.; Ismail, A.; Chihib, N.-E. Enhanced antimicrobial, antibiofilm and ecotoxic activities of nanoencapsulated carvacrol and thymol as compared to their free counterparts. Food Control 2023, 143, 109317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hage, M.; Khelissa, S.; Abdallah, M.; Akoum, H.; Chihib, N.-E.; Jama, C. Cold plasma assisted deposition of organosilicon coatings on stainless steel for prevention of adhesion of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis. Biofouling 2021, 37, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abderrahmane, R.; Hafssa, H.; Nabila, S.; Guido, F.; Roberta, A.; Hichem, B. Comparative study of the variability of chemical composition and antibacterial activity between two Moroccan endemic species essential oils: Origanum grosiiPau & Font Quer and Origanum elongatum (Bonnet) Emberger & Maire. Egypt. J. Chem. 2021, 64, 4773–4782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Lao, Y.; Pan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, H.; Gong, L.; Xie, N.; Mo, C.-H. Synergistic Antimicrobial Effectiveness of Plant Essential Oil and Its Application in Seafood Preservation: A Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, W.; Cheong, K.; Teng, B. Characterization of seaweed polysaccharide-based bilayer films containing essential oils with antibacterial activity. LWT 2021, 150, 111961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalerandi, E.; Flores, G.A.; Palacio, M.; Defagó, M.T.; Carpinella, M.C.; Valladares, G.; Bertoni, A.; Palacios, S.M. Understanding Synergistic Toxicity of Terpenes as Insecticides: Contribution of Metabolic Detoxification in Musca domestica. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal-Mercado, A.T.; Juarez, J.; Valdez, M.A.; Ayala-Zavala, J.F.; Del-Toro-Sánchez, C.L.; Encinas-Basurto, D. Hydrophobic Chitosan Nanoparticles Loaded with Carvacrol against Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms. Molecules 2022, 27, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenkranz, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, P.; Vlot, A.C. Volatile terpenes—Mediators of plant-to-plant communication. Plant J. 2021, 108, 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.A.R.; Silva, L.P.; Ferreira, O.; Schröder, B.; Coutinho, J.A.P.; Pinho, S.P. Terpenes solubility in water and their environmental distribution. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 241, 996–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benabdelouahab, Y.; Muñoz-Moreno, L.; Frik, M.; de la Cueva-Alique, I.; El Amrani, M.A.; Contel, M.; Bajo, A.M.; Cuenca, T.; Royo, E. Hydrogen Bonding and Anticancer Properties of Water-Soluble Chiral p-Cymene RuII Compounds with Amino-Oxime Ligands. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 2015, 2295–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibn El Alami, M.S.; El Amrani, M.A.; Dahdouh, A.; Roussel, P.; Suisse, I.; Mortreux, A. α-Amino-Oximes Based on Optically Pure Limonene: A New Ligands Family for Ruthenium-Catalyzed Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation: A New Ligands Family for ruthenium-catalyzed asymmetric transfer hydrogenation. Chirality 2012, 24, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khelissa, S.; El Fannassi, Y.; Mechmechani, S.; Alhuthali, S.; El Amrani, M.A.; Gharsallaoui, A.; Barras, A.; Chihib, N.-E. Water-Soluble Ruthenium (II) Complex Derived From Optically Pure Limonene and Its Microencapsulation Are Efficient Tools Against Bacterial Food Pathogen Biofilms: Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Enteroccocus faecalis, and Listeria monocytogenes. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 711326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chohan, Z.H.; Munawar, A.; Supuran, C.T. Transition Metal Ion Complexes of Schiff-bases. Synthesis, Characterization and Antibacterial Properties. Met.-Based Drugs 2001, 8, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boughougal, A. Synthesis and Characterization of Antimicrobial Coordination Compounds. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Lyon, Université Abbès Laghrour (Algeria), 2018. Available online: https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03228256 (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Mittapally, S.; Taranum, R.; Parveen, S. Metal ions as antibacterial agents. J. Drug Deliv. Ther. 2018, 8, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezealigo, U.S.; Ezealigo, B.N.; Aisida, S.O.; Ezema, F.I. Iron oxide nanoparticles in biological systems: Antibacterial and toxicology perspective. JCIS Open 2021, 4, 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Ebers Papyrus (or Thebes Papyrus). Available online: http://ceed-diabete.org/blog/le-papyrus-debers-ou-papyrus-de-thebes/ (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Imran, M.; Iqbal, J.; Iqbal, S.; Ijaz, N. In Vitro Antibacterial Studies of Ciprofloxacin-imines and Their Complexes with Cu(II),Ni(II),Co(II), and Zn(II). Turk. J. Biol. 2007, 31, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-López, F.; Martínez-Meléndez, A.; Garza-González, E. How Does Hospital Microbiota Contribute to Healthcare-Associated Infections? Microorganisms 2023, 11, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, A.; McCallum, J.; Kimmel, S.D.; Venkataramani, A.S. Resident Mortality and Worker Infection Rates From COVID-19 Lower In Union Than Nonunion US Nursing Homes, 2020–2021. Health Aff. 2022, 41, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNicholl, A.G.; O’Morain, C.A.; Megraud, F.; Gisbert, J.P.; As Scientific Committee of the Hp-Eureg on Behalf of the National Coordinators. Protocol of the European Registry on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection (Hp-EuReg). Helicobacter 2019, 24, e12630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Healthcare-Associated Infections. HAIC Activities, HAI and Antibiotic Use Prevalence Survey. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hai/eip/antibiotic-use.html (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- 13.3: Pathogens in the Normal Flora. Available online: https://bio.libretexts.org/Courses/Mansfield_University_of_Pennsylvania/BSC_3271%3A_Microbiology_for_Health_Sciences_Sp21_(Kagle)/13%3A_The_Human_Microbiota/13.03%3A_Pathogens_in_the_Normal_Flora (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- O’Malley, C.A. Infection Control in Cystic Fibrosis: Cohorting, Cross-Contamination, and the Respiratory Therapist. Respir. Care 2009, 54, 641–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motbainor, H.; Bereded, F.; Mulu, W. Multi-drug resistance of blood stream, urinary tract and surgical site nosocomial infections of Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa among patients hospitalized at Felegehiwot referral hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhakar, C. Infection Control: Updates; BoD—Books on Demand: Norderstedt, Germany, 2012; ISBN 978-953-51-0055-3. [Google Scholar]

- Khelissa, S.O.; Abdallah, M.; Jama, C.; Faille, C.; Chihib, N.-E. Bacterial contamination and biofilm formation on abiotic surfaces and strategies to overcome their persistence. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2017, 21, 3326–3346. [Google Scholar]

- Jamal, M.; Ahmad, W.; Andleeb, S.; Jalil, F.; Imran, M.; Nawaz, M.A.; Hussain, T.; Ali, M.; Rafiq, M.; Kamil, M.A. Bacterial biofilm and associated infections. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2018, 81, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebeaux, D.; Ghigo, J.-M. Biofilm-associated infections: Therapeutic prospects from basic research? Méd. Sci. 2012, 28, 727–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Moser, C.; Wang, H.-Z.; Høiby, N.; Song, Z.-J. Strategies for combating bacterial biofilm infections. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2015, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane Biotech. Biofilm—Problem Areas. Available online: https://kanebiotech.com/fr/biofilm-problem-areas/ (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Gilmore, B.F.; Denyer, S.P. Hugo and Russell’s Pharmaceutical Microbiology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; ISBN 978-1-119-43455-9. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, K.; Li, J.; Kong, Q.; Wang, C.; Ye, N.; Xia, G. Risk factors for surgical site infection in a teaching hospital: A prospective study of 1138 patients. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2015, 9, 1171–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lastinger, L.M.; Alvarez, C.R.; Kofman, A.; Konnor, R.Y.; Kuhar, D.T.; Nkwata, A.; Patel, P.R.; Pattabiraman, V.; Xu, S.Y.; Dudeck, M.A. Continued increases in the incidence of healthcare-associated infection (HAI) during the second year of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2022, 44, 997–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.X.; Butler, D.S.; Hamblin, M.; Monack, D.M. One species, different diseases: The unique molecular mechanisms that underlie the pathogenesis of typhoidal Salmonella infections. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2023, 72, 102262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scallan, E.; Hoekstra, R.M.; Angulo, F.J.; Tauxe, R.V.; Widdowson, M.-A.; Roy, S.L.; Jones, J.L.; Griffin, P.M. Foodborne Illness Acquired in the United States—Major Pathogens. Emerg. Infect. Dis. J. 2011, 17, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Guo, X.; Tian, L.; Wang, N.; Li, Y.; Kushmaro, A.; Marks, R.; Sun, Q. Antibiofilm activity of 3,3’-diindolylmethane on Staphylococcus aureus and its disinfection on common food-contact surfaces. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2022, 11, 1222–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, E.; Gugsa, G.; Ahmed, M. Review on Major Food-Borne Zoonotic Bacterial Pathogens. J. Trop. Med. 2020, 2020, e4674235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Five Keys to Safer Food Manual; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, B.; Otta, S.K.; Karunasagar, I.; Karunasagar, I. Biofilm formation by Salmonella spp. on food contact surfaces and their sensitivity to sanitizers. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2001, 64, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.K.; Song, M.G.; Park, S.Y. Impact of Quercetin against Salmonella Typhimurium Biofilm Formation on Food-Contact Surfaces and Molecular Mechanism Pattern. Foods 2022, 11, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Yang, C.; Bao, X.; Chen, F.; Guo, X. Strategies for controlling biofilm formation in food industry. Grain Oil Sci. Technol. 2022, 5, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tang, B.; Gu, Q.; Yu, X. Elimination of the formation of biofilm in industrial pipes using enzyme cleaning technique. MethodsX 2014, 1, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechmechani, S.; Khelissa, S.; Gharsallaoui, A.; Omari, K.E.; Hamze, M.; Chihib, N.-E. Hurdle technology using encapsulated enzymes and essential oils to fight bacterial biofilms. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 2311–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechmechani, S.; Gharsallaoui, A.; El Omari, K.; Fadel, A.; Hamze, M.; Chihib, N.-E. Hurdle technology based on the use of microencapsulated pepsin, trypsin and carvacrol to eradicate Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterococcus faecalis biofilms. Biofouling 2022, 38, 903–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yammine, J.; Chihib, N.-E.; Gharsallaoui, A.; Dumas, E.; Ismail, A.; Karam, L. Essential oils and their active components applied as: Free, encapsulated and in hurdle technology to fight microbial contaminations. A review. Heliyon 2022, 8, e12472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blot, K.; Hammami, N.; Blot, S.; Vogelaers, D.; Lambert, M.-L. Gram-negative central line-associated bloodstream infection incidence peak during the summer: A national seasonality cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddadin, Y.; Annamaraju, P.; Regunath, H. Central Line Associated Blood Stream Infections. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nakaya, Y.; Imasaki, M.; Shirano, M.; Shimizu, K.; Yagi, N.; Tsutsumi, M.; Yoshida, M.; Yoshimura, T.; Hayashi, Y.; Nakao, T.; et al. Peripherally inserted central venous catheters decrease central line-associated bloodstream infections and change microbiological epidemiology in adult hematology unit: A propensity score-adjusted analysis. Ann. Hematol. 2022, 101, 2069–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanikolopoulou, A.; Maltezou, H.C.; Gargalianos-Kakolyris, P.; Michou, I.; Kalofissoudis, Y.; Moussas, N.; Pantazis, N.; Kotteas, E.; Syrigos, K.N.; Pantos, C.; et al. Central-line-associated bloodstream infections, multi-drug-resistant bacteraemias and infection control interventions: A 6-year time-series analysis in a tertiary care hospital in Greece. J. Hosp. Infect. 2022, 123, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan, K.A.; Cousins, S.M.; Porter, D.D.; O’Brien, M.; Rudkin, S.; Lambertson, B.; Hoang, D.; Dangodara, A.A.; Huang, S.S. Electronic health record solutions to reduce central line-associated bloodstream infections by enhancing documentation of central line insertion practices, line days, and daily line necessity. Am. J. Infect. Control 2016, 44, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.K.; Gohil, S.K.; Quan, K.; Huang, S.S. Marked reduction in compliance with central line insertion practices (CLIP) when accounting for missing CLIP data and incomplete line capture. Am. J. Infect. Control 2016, 44, 242–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebrolu, P.; Colombo, R.E.; Baer, S.; Gallaher, T.R.; Atwater, S.; Kheda, M.; Nahman, N.S.; Kintziger, K.W. Bacteremia in hemodialysis patients with hepatitis C. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 349, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinclair, M.R.; Souli, M.; Ruffin, F.; Park, L.P.; Dagher, M.; Eichenberger, E.M.; Maskarinec, S.A.; Thaden, J.T.; Mohnasky, M.; Wyatt, C.M.; et al. Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia Among Patients Receiving Maintenance Hemodialysis: Trends in Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2022, 79, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štefánek, M.; Wenner, S.; Borges, V.; Pinto, M.; Gomes, J.P.; Rodrigues, J.; Faria, I.; Pessanha, M.A.; Martins, F.; Sabino, R.; et al. Antimicrobial Resistance and Biofilms Underlying Catheter-Related Bloodstream Coinfection by Enterobacter cloacae Complex and Candida parapsilosis. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arthur, N.; Kaur, I.; Carey, A.J. Evaluation of the applicability of the current CDC pediatric ventilator-associated events (PedVAE) surveillance definition in the neonatal intensive care unit population. BMC Pediatr. 2022, 22, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chomton, M.; Brossier, D.; Sauthier, M.; Vallières, E.; Dubois, J.; Emeriaud, G.; Jouvet, P. Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia and Events in Pediatric Intensive Care: A Single Center Study. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 19, 1106–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edzards, M.J.; Jacobs, M.B.; Song, X.; Basu, S.K.; Hamdy, R.F. Polymyxin flushes for endotracheal tube suction catheters in extremely low birth-weight infants: Any benefit in preventing ventilator-associated events? Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2023, 44, 1345–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iosifidis, E.; Coffin, S. Ventilator-associated Events in Children: Controversies and Research Needs. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2020, 39, e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karandikar, M.V.; Coffin, S.E.; Priebe, G.P.; Sandora, T.J.; Logan, L.K.; Larsen, G.Y.; Toltzis, P.; Gray, J.E.; Klompas, M.; Sammons, J.S.; et al. Variability in antimicrobial use in pediatric ventilator-associated events. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2019, 40, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-López, Y.; Campins-Martí, M.; Slöcker-Barrio, M.; Bustinza, A.; Alejandre, C.; Jordán-García, I.; Ortiz-Álvarez, A.; López-Castilla, J.D.; Pérez, E.; Schüffelmann, C.; et al. Ventilator-associated events in children: A multicentre prospective cohort study. Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain Med. 2022, 41, 101072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassetti, M.; Mularoni, A.; Giacobbe, D.R.; Castaldo, N.; Vena, A. New Antibiotics for Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia and Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 43, 280–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Domenico, E.G.; Oliva, A.; Guembe, M. The Current Knowledge on the Pathogenesis of Tissue and Medical Device-Related Biofilm Infections. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, T.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Li, C.; Worthington, H.V.; Hua, F. Oral hygiene care for critically ill patients to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 12, CD008367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chenoweth, C.E. Urinary Tract Infections: 2021 Update. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 35, 857–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Yuan, Q.; Gao, J.; Liu, Y.; Jin, X.; Tang, L.; Cao, Y. Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in the diagnosis of urinary tract infection in patients undergoing cutaneous ureterostomy. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 991011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubi, H.; Mudey, G.; Kunjalwar, R. Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection (CAUTI). Cureus 2022, 14, e30385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q.; Wu, C.; Yu, X.; Chen, X.; Pan, G.; Chen, B. Current material engineering strategies to prevent catheter encrustation in urinary tracts. Mater. Today Bio 2022, 16, 100413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, R.; Mao, X.; Xu, Y.; Qiu, X.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Y.; Pang, B.; Chen, M.; Cao, S.; Bao, L.; et al. Polysaccharides from Vaccaria segetalis seeds reduce urinary tract infections by inhibiting the adhesion and invasion abilities of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1004751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubitzsch, H.; Tarar, W.; Claus, B.; Gabbieri, D.; Falk, V.; Christ, T. Risks and Challenges of Surgery for Aortic Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis. Heart Lung Circ. 2018, 27, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanz, J.; Reardon, M.J.; Pilgrim, T.; Stortecky, S.; Deeb, G.M.; Chetcuti, S.; Yakubov, S.J.; Gleason, T.G.; Huang, J.; Windecker, S. Incidence and Outcomes of Infective Endocarditis After Transcatheter or Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e020368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangner, N.; del Val, D.; Abdel-Wahab, M.; Crusius, L.; Durand, E.; Ihlemann, N.; Urena, M.; Pellegrini, C.; Giannini, F.; Gasior, T.; et al. Surgical Treatment of Patients with Infective Endocarditis After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 79, 772–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, M.P.; DeSantis, A.J.; Janjua, H.M.; Kulshrestha, S.; Kuo, P.C.; Lozonschi, L. Outcomes of Transcatheter and Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement in Distressed Socioeconomic Communities. Cureus 2022, 14, e23643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Ali, A.; Schnackenburg, P.; Horke, K.M.; Oberbach, A.; Schlichting, N.; Sadoni, S.; Rizas, K.; Braun, D.; Luehr, M.; et al. Surgery for Aortic Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis in the Transcatheter Era. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serna-Gallegos, D.; Sultan, I. Aortic root replacement: What is in your wallet? Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2022, 62, ezac280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talha, K.M.; McHugh, J.W.; DeSimone, D.C.; Fischer, K.M.; Eleid, M.F.; St Sauver, J.; Sohail, M.R.; Baddour, L.M. Bloodstream infections in patients with transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2021, 101, 115456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aluru, J.S.; Barsouk, A.; Saginala, K.; Rawla, P.; Barsouk, A. Valvular Heart Disease Epidemiology. Med. Sci. 2022, 10, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomström-Lundqvist, C.; Traykov, V.; Erba, P.A.; Burri, H.; Nielsen, J.C.; Bongiorni, M.G.; Poole, J.; Boriani, G.; Costa, R.; Deharo, J.-C.; et al. European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) international consensus document on how to prevent, diagnose, and treat cardiac implantable electronic device infections-endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), the Latin American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS), International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious Diseases (ISCVID) and the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur. Heart J. 2020, 22, 515–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesdachai, S.; Baddour, L.M.; Sohail, M.R.; Palraj, B.R.; Madhavan, M.; Tabaja, H.; Fida, M.; Lahr, B.D.; DeSimone, D.C. Evaluation of European Heart Rhythm Association consensus in patients with cardiovascular implantable electronic devices and Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Heart Rhythm 2022, 19, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dilsizian, V.; Budde, R.P.J.; Chen, W.; Mankad, S.V.; Lindner, J.R.; Nieman, K. Best Practices for Imaging Cardiac Device-Related Infections and Endocarditis: A JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging Expert Panel Statement. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 15, 891–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ashry, A.H.; Hussein, M.S.A.; Saad, K.; El Elhoufey, A. Clinical utility of sonication for diagnosing infection and colonization of cardiovascular implantable electronic devices. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2021, 210, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khubrani, R.; Alghamdi, A.S.; Alsubaie, A.A.; Alenazi, T.; Almutairi, A.; Alsunaydi, F. Rate of Cardiovascular Implantable Electronic Device-Related Infection at a Tertiary Hospital in Saudi Arabia: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Cureus 2022, 14, e27078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranick, S.; Mishra, N.; Theertham, A.; Vo, H.; Hiltner, E.; Coromilas, J.; Kassotis, J. A Survey of Antibiotic Use During Insertion of Cardiovascular Implantable Devices Among United States Implanters. Angiology 2022, 74, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narui, R.; Nakajima, I.; Norton, C.; Holmes, B.B.; Yoneda, Z.T.; Phillips, N.; Schaffer, A.; Tinianow, A.; Aboud, A.A.; Stevenson, W.G.; et al. Risk Factors for Repeat Infection and Mortality After Extraction of Infected Cardiovascular Implantable Electronic Devices. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2021, 7, 1182–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, R.; Mark, G.E.; El-Chami, M.F.; Biffi, M.; Probst, V.; Lambiase, P.D.; Miller, M.A.; McClernon, T.; Hansen, L.K.; Knight, B.P.; et al. Process mapping strategies to prevent subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator infections. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2022, 33, 1628–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Arriba-Fernández, A.; Molina-Cabrillana, J.; Serra-Majem, L.; García-de Carlos, P. Assessment of the surgical site infection in colon surgery and antibiotic prophylaxis adequacy: A multi-center incidence study. Cir. Esp. 2022, 100, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rud, V.O.; Salmanov, A.G.; Vitiuk, A.D.; Hrynchuk, S.Y.; Bober, A.S.; Hrynchuk, O.B.; Berestooy, O.A.; Chernega, T.V. Vaginal cuff infection after hysterectomy in Ukraine. Wiadomosci Lek. Wars. Pol. 2021, 74, 196–201. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, C.; Enns, J.; Bennett, C.; Sangi-Haghpeykar, H.; Lundeen, S.; Eppes, C. Reducing abdominal hysterectomy surgical site infections: A multidisciplinary quality initiative. Am. J. Infect. Control 2020, 48, 1292–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhu, C.; Yi, H.; Sun, H.; Ma, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, K.; Ai, F.; Wu, Z.; Yin, Q.; et al. Incidence and management of surgical site infection in the cervical spine following a transoral approach. Int. Orthop. 2022, 46, 2329–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, G.A.; O’Shea, E.; Nazir, S.F.; Hanniffy, R.; Chawke, G.; Rothwell, A.; Gilsenan, F.; MacIntyre, A.; Meenan, A.M.; O’Sullivan, N.; et al. Reducing Caesarean Section Surgical Site Infection (SSI) by 50%: A Collaborative Approach. J. Healthc. Qual. 2021, 43, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, M.P.; Song, A.T.W.; Oshiro, I.C.V.; Andraus, W.; D’Albuquerque, L.A.C.; Abdala, E. Surgical site infection after liver transplantation in the era of multidrug-resistant bacteria: What new risks should be considered? Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2021, 99, 115220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grammatico-Guillon, L.; Miliani, K.; Banaei-Bouchareb, L.; Solomiac, A.; Sambour, J.; May-Michelangeli, L.; Astagneau, P. A computerized indicator for surgical site infection (SSI) assessment after total hip or total knee replacement: The French ISO-ORTHO indicator. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2022, 43, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, N.; Begier, E.; Lin, K.J.; Yu, H. Culture-Confirmed Staphylococcus aureus Infection after Elective Hysterectomy: Burden of Disease and Risk Factors. Surg. Infect. 2020, 21, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auñón, Á.; Tovar-Bazaga, M.; Blanco-García, A.; García-Cañete, J.; Parrón, R.; Esteban, J. Does a New Antibiotic Scheme Improve the Outcome of Staphylococcus aureus-Caused Acute Prosthetic Joint Infections (PJI) Treated with Debridement, Antibiotics and Implant Retention (DAIR)? Antibiotics 2022, 11, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, B.P.; Heim, C.E.; West, S.C.; Chaudhari, S.S.; Ali, H.; Thomas, V.C.; Kielian, T. Role of Staphylococcus aureus Formate Metabolism during Prosthetic Joint Infection. Infect. Immun. 2022, 90, e0042822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espíndola, R.; Vella, V.; Benito, N.; Mur, I.; Tedeschi, S.; Zamparini, E.; Hendriks, J.G.E.; Sorlí, L.; Murillo, O.; Soldevila, L.; et al. Rates and Predictors of Treatment Failure in Staphylococcus aureus Prosthetic Joint Infections According to Different Management Strategies: A Multinational Cohort Study-The ARTHR-IS Study Group. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2022, 11, 2177–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herry, Y.; Lesens, O.; Bourgeois, G.; Maillet, M.; Bricca, R.; Cazorla, C.; Karsenty, J.; Chroboczek, T.; Bouaziz, A.; Saison, J.; et al. Staphylococcus lugdunensis prosthetic joint infection: A multicentric cohort study. J. Infect. 2022, 85, 652–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papalini, C.; Pucci, G.; Cenci, G.; Mencacci, A.; Francisci, D.; Caraffa, A.; Antinolfi, P.; Pasticci, M.B. Prosthetic joint infection diagnosis applying the three-level European Bone and Joint Infection Society (EBJIS) approach. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2022, 41, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathy, S.; Shah, S.; Raja Sager, A.; Rangan, A.; Durugu, S. Staphylococcus lugdunensis: Review of Epidemiology, Complications, and Treatment. Cureus 2020, 12, e8801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, V.; Washburn, F.; Barouni, B.; Saeed, M. A Rare Case of Prosthetic Joint Infection with Streptococcus gordonii. Am. J. Case Rep. 2022, 23, e937271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prié, H.; Meyssonnier, V.; Kerroumi, Y.; Heym, B.; Lidove, O.; Marmor, S.; Zeller, V. Pseudomonas aeruginosa prosthetic joint-infection outcomes: Prospective, observational study on 43 patients. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 1039596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wouthuyzen-Bakker, M.; Sebillotte, M.; Huotari, K.; Escudero Sánchez, R.; Benavent, E.; Parvizi, J.; Fernandez-Sampedro, M.; Barbero, J.M.; Garcia-Cañete, J.; Trebse, R.; et al. Lower Success Rate of Débridement and Implant Retention in Late Acute versus Early Acute Periprosthetic Joint Infection Caused by Staphylococcus spp. Results from a Matched Cohort Study. Clin. Orthop. 2020, 478, 1348–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Kong, Y.; Ye, J.; Wang, A.; Si, W. Microbiological pattern of prosthetic hip and knee infections: A high-volume, single-centre experience in China. J. Med. Microbiol. 2021, 70, 001305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zardi, E.M.; Franceschi, F. Prosthetic joint infection. A relevant public health issue. J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 1888–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwirzitz, B.; Wetzels, S.U.; Dixon, E.D.; Fleischmann, S.; Selberherr, E.; Thalguter, S.; Quijada, N.M.; Dzieciol, M.; Wagner, M.; Stessl, B. Co-Occurrence of Listeria spp. and Spoilage Associated Microbiota During Meat Processing Due to Cross-Contamination Events. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 632935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakrzewski, A.J.; Kurpas, M.; Zadernowska, A.; Chajęcka-Wierzchowska, W.; Fraqueza, M.J. A Comprehensive Virulence and Resistance Characteristics of Listeria monocytogenes Isolated from Fish and the Fish Industry Environment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolocan, A.S.; Oniciuc, E.A.; Alvarez-Ordóñez, A.; Wagner, M.; Rychli, K.; Jordan, K.; Nicolau, A.I. Putative Cross-Contamination Routes of Listeria monocytogenes in a Meat Processing Facility in Romania. J. Food Prot. 2015, 78, 1664–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake, F.B.; van Overbeek, L.S.; Baars, J.J.P.; Abee, T.; den Besten, H.M.W. Variability in growth and biofilm formation of Listeria monocytogenes in Agaricus bisporus mushroom products. Food Res. Int. 2023, 165, 112488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Sun, Y.; Hou, W.; Zhao, W.; Wang, P.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, X.; Wang, D. Infection behavior of Listeria monocytogenes on iceberg lettuce (Lactuca sativa var. capitata). Food Res. Int. 2023, 165, 112487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dortu, C.; Huch, M.; Holzapfel, W.H.; Franz, C.M.A.P.; Thonart, P. Anti-listerial activity of bacteriocin-producing Lactobacillus curvatus CWBI-B28 and Lactobacillus sakei CWBI-B1365 on raw beef and poultry meat. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 47, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katla, T.; Møretrø, T.; Sveen, I.; Aasen, I.M.; Axelsson, L.; Rørvik, L.M.; Naterstad, K. Inhibition of Listeria monocytogenes in chicken cold cuts by addition of sakacin P and sakacin P-producing Lactobacillus sakei. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2002, 93, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghalfi, H.; Benkerroum, N.; Doguiet, D.D.K.; Bensaid, M.; Thonart, P. Effectiveness of cell-adsorbed bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus curvatus CWBI-B28 and selected essential oils to control Listeria monocytogenes in pork meat during cold storage. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 44, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, A.N.; Gibson, K.E. Efficacy of Manufacturer Recommendations for the Control of Salmonella Typhimurium and Listeria monocytogenes in Food Ink Capsules Utilized in 3D Food Printing Systems. J. Food Prot. 2023, 86, 100030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, E.N.; Van Doren, J.M.; Leonard, C.L.; Datta, A.R. Prevalence of Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella spp., Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli, and Campylobacter spp. in raw milk in the United States between 2000 and 2019: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Food Prot. 2023, 86, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen Trang, P.; Thi Anh Ngoc, T.; Masuda, Y.; Hohjoh, K.-I.; Miyamoto, T. Biofilm Formation from Listeria monocytogenes Isolated From Pangasius Fish-processing Plants. J. Food Prot. 2023, 86, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, S.Y.; Cho, T.J.; Yu, H.; Park, S.G.; Kim, S.-R.; Kim, S.A.; Rhee, M.S. Efficacy of combined caprylic acid and thymol treatments for inactivation of Listeria monocytogenes on enoki mushrooms in household and food-service establishments. Food Res. Int. 2023, 166, 112601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marouani-Gadri, N.; Augier, G.; Carpentier, B. Characterization of bacterial strains isolated from a beef-processing plant following cleaning and disinfection—Influence of isolated strains on biofilm formation by Sakaï and EDL 933 E. coli O157:H7. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2009, 133, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thévenot, D.; Delignette-Muller, M.L.; Christieans, S.; Vernozy-Rozand, C. Prevalence of Listeria monocytogenes in 13 dried sausage processing plants and their products. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2005, 102, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csadek, I.; Vankat, U.; Schrei, J.; Graf, M.; Bauer, S.; Pilz, B.; Schwaiger, K.; Smulders, F.J.M.; Paulsen, P. Treatment of Ready-To-Eat Cooked Meat Products with Cold Atmospheric Plasma to Inactivate Listeria and Escherichia coli. Foods 2023, 12, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bywater, A.; Alexander, K.; Eifert, J.; Strawn, L.K.; Ponder, M.A. Survival of Inoculated Campylobacter jejuni and Escherichia coli O157:H7 on Kale During Refrigerated Storage. J. Food Prot. 2023, 86, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalchayanand, N.; Wang, R.; Brown, T.; Wheeler, T.L. Efficacy of Short Thermal Treatment Time Against Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Salmonella on the Surface of Fresh Beef. J. Food Prot. 2023, 86, 100040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, R.; Bloomfield, S.; Adley, C.C. A study of cross-contamination of food-borne pathogens in the domestic kitchen in the Republic of Ireland. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2002, 76, s0168–s1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peles, F.; Wagner, M.; Varga, L.; Hein, I.; Rieck, P.; Gutser, K.; Keresztúri, P.; Kardos, G.; Turcsányi, I.; Béri, B.; et al. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from bovine milk in Hungary. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007, 118, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadat, A.; Shata, R.R.; Farag, A.M.M.; Ramadan, H.; Alkhedaide, A.; Soliman, M.M.; Elbadawy, M.; Abugomaa, A.; Awad, A. Prevalence and Characterization of PVL-Positive Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Raw Cow’s Milk. Toxins 2022, 14, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekhloufi, O.A.; Chieffi, D.; Hammoudi, A.; Bensefia, S.A.; Fanelli, F.; Fusco, V. Prevalence, Enterotoxigenic Potential and Antimicrobial Resistance of Staphylococcus aureus and Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Isolated from Algerian Ready to Eat Foods. Toxins 2021, 13, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heydari-Majd, M.; Shadan, M.R.; Rezaeinia, H.; Ghorani, B.; Bameri, F.; Sarabandi, K.; Khoshabi, F. Electrospun plant protein-based nanofibers loaded with sakacin as a promising bacteriocin source for active packaging against Listeria monocytogenes in quail breast. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 391–393, 110143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, H.; Pei, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, R.; Lu, S.; Li, B.; Dong, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, X.; Ji, H. Construction of a dynamic model to predict the growth of Staphylococcus aureus and the formation of enterotoxins during Kazak cheese maturation. Food Microbiol. 2023, 112, 104234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deddefo, A.; Mamo, G.; Asfaw, M.; Amenu, K. Factors affecting the microbiological quality and contamination of farm bulk milk by Staphylococcus aureus in dairy farms in Asella, Ethiopia. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, M.C.D.P.B.; Campos, M.R.H.; Borges, L.J.; Kipnis, A.; Pimenta, F.C.; Serafini, Á.B. Comparison of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from food handlers, raw bovine milk and Minas Frescal cheese by antibiogram and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis following SmaI digestion. Food Control 2008, 19, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Tang, W.; Li, Y.; Han, Y.; Cui, L.; Sun, S. Comparative Analysis between Salmonella enterica Isolated from Imported and Chinese Native Chicken Breeds. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deliephan, A.; Dhakal, J.; Subramanyam, B.; Aldrich, C.G. Use of Organic Acid Mixtures Containing 2-Hydroxy-4-(Methylthio) Butanoic Acid (HMTBa) to Mitigate Salmonella enterica, Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli (STEC) and Aspergillus flavus in Pet Food Kibbles. Animals 2023, 13, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deliephan, A.; Dhakal, J.; Subramanyam, B.; Aldrich, C.G. Mitigation of Salmonella on Food Contact Surfaces by Using Organic Acid Mixtures Containing 2-Hydroxy-4-(methylthio) Butanoic Acid (HMTBa). Foods 2023, 12, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumaningrum, H.D.; Van Asselt, E.D.; Beumer, R.R.; Zwietering, M.H. A Quantitative Analysis of Cross-Contamination of Salmonella and Campylobacter spp. Via Domestic Kitchen Surfaces. J. Food Prot. 2004, 67, 1892–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topalcengiz, Z.; Friedrich, L.M.; Danyluk, M.D. Salmonella transfer potential between tomatoes and cartons used for distribution. J. Food Prot. 2023, 86, 100016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oscar, T.P. Poultry Food Assess Risk Model for Salmonella and Chicken Gizzards: I. Initial Contamination. J. Food Prot. 2023, 86, 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabin, N.; Zheng, Y.; Opoku-Temeng, C. Biofilm formation mechanisms and targets for developing antibiofilm agents. Future Med. Chem. 2015, 7, 493–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauer, K.; Stoodley, P.; Goeres, D.M.; Hall-Stoodley, L.; Burmølle, M.; Stewart, P.S.; Bjarnsholt, T. The biofilm life cycle: Expanding the conceptual model of biofilm formation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 608–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resch, A.; Leicht, S.; Saric, M.; Pásztor, L.; Jakob, A.; Götz, F.; Nordheim, A. Comparative proteome analysis of Staphylococcus aureus biofilm and planktonic cells and correlation with transcriptome profiling. Proteomics 2006, 6, 1867–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, P. Extracellular polymeric substances, a key element in understanding biofilm phenotype. AIMS Microbiol. 2018, 4, 274–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seviour, T.; Derlon, N.; Dueholm, M.S.; Flemming, H.-C.; Girbal-Neuhauser, E.; Horn, H.; Kjelleberg, S.; van Loosdrecht, M.C.M.; Lotti, T.; Malpei, M.F.; et al. Extracellular polymeric substances of biofilms: Suffering from an identity crisis. Water Res. 2019, 151, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Hu, W.; Tian, Z.; Yuan, D.; Yi, G.; Zhou, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Zhu, J.; Li, M. Developing natural products as potential anti-biofilm agents. Chin. Med. 2019, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouyahya, A.; Chamkhi, I.; Balahbib, A.; Rebezov, M.; Shariati, M.A.; Wilairatana, P.; Mubarak, M.S.; Benali, T.; El Omari, N. Mechanisms, Anti-Quorum-Sensing Actions, and Clinical Trials of Medicinal Plant Bioactive Compounds against Bacteria: A Comprehensive Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, C.; Feng, F.; Tang, J.; Tang, X.; Wu, D.; Xiao, R.; Min, X.; Tang, C.-J. A review of quorum sensing regulating heavy metal resistance in anammox process: Relations, mechanisms and prospects. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Lian, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, L. The role and mechanism of quorum sensing on environmental antimicrobial resistance. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 322, 121238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Cao, B.; Yang, L.; Gu, J.-D. Biofilm control by interfering with c-di-GMP metabolism and signaling. Biotechnol. Adv. 2022, 56, 107915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rather, M.A.; Saha, D.; Bhuyan, S.; Jha, A.N.; Mandal, M. Quorum Quenching: A Drug Discovery Approach Against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiol. Res. 2022, 264, 127173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Chen, W.-J.; Bhatt, K.; Zhou, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, L.-H.; Chen, S.; Wang, J. Innovative microbial disease biocontrol strategies mediated by quorum quenching and their multifaceted applications: A review. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1063393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, H.; Choo, S.; Rajeswari Mahalingam, S.R.; Adisuri, D.S.; Madhavan, P.; Md. Akim, A.; Chong, P.P. Approaches for Mitigating Microbial Biofilm-Related Drug Resistance: A Focus on Micro- and Nanotechnologies. Molecules 2021, 26, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, A.; Ghigo, J.-M. Bacterial biofilms. Bull. Fr. Vet. Acad. 2006, 159, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markova, J.A.; Anganova, E.V.; Turskaya, A.L.; Bybin, V.A.; Savilov, E.D. Regulation of Escherichia coli Biofilm Formation (Review). Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2018, 54, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemming, H.-C.; Wingender, J. Relevance of microbial extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs)—Part I: Structural and ecological aspects. Water Sci. Technol. 2001, 43, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemming, H.-C.; Wingender, J. The biofilm matrix. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, N.; Fatima, S.W.; Kumar, S.; Sinha, R.; Khare, S.K. Antimicrobial resistance in biofilms: Exploring marine actinobacteria as a potential source of antibiotics and biofilm inhibitors. Biotechnol. Rep. 2021, 30, e00613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdallah, M.; Khelissa, O.; Ibrahim, A.; Benoliel, C.; Heliot, L.; Dhulster, P.; Chihib, N.-E. Impact of growth temperature and surface type on the resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus biofilms to disinfectants. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 214, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rather, M.A.; Gupta, K.; Mandal, M. Microbial biofilm: Formation, architecture, antibiotic resistance, and control strategies. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2021, 52, 1701–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gedefie, A.; Demsis, W.; Ashagrie, M.; Kassa, Y.; Tesfaye, M.; Tilahun, M.; Bisetegn, H.; Sahle, Z. Acinetobacter baumannii Biofilm Formation and Its Role in Disease Pathogenesis: A Review. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 3711–3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciofu, O.; Moser, C.; Jensen, P.Ø.; Høiby, N. Tolerance and resistance of microbial biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houin, R.; Euzéby, J. Grand Dictionnaire illustré de Parasitologie médicale et vétérinaire Editions Médicales Internationales—Lavoisier éditeurs, 2008. Bull. Académie Vét. Fr. 2009, 162, 187. [Google Scholar]

- Horváth, I.T.; Anastas, P.T. Innovations and Green Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 2169–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessel, V.; Tran, N.N.; Asrami, M.R.; Tran, Q.D.; Long, N.V.D.; Escribà-Gelonch, M.; Tejada, J.O.; Linke, S.; Sundmacher, K. Sustainability of green solvents—Review and perspective. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 410–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, R.K.; Ranjit, A.; Sharma, K.; Prasad, P.; Shang, X.; Gowda, K.G.M.; Keum, Y.-S. Bioactive Compounds of Citrus Fruits: A Review of Composition and Health Benefits of Carotenoids, Flavonoids, Limonoids, and Terpenes. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, B.B.; Gruissem, W.; Jones, R.L. (Eds.) Biochemistry & Molecular Biology of Plants; American Society of Plant Physiologists: Rockville, MD, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-943088-37-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ciriminna, R.; Lomeli-Rodriguez, M.; Carà, P.D.; Lopez-Sanchez, J.A.; Pagliaro, M. Limonene: A versatile chemical of the bioeconomy. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 15288–15296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.S.; Lim, Y.; Lee, K.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, I.-S. Terpenes from Forests and Human Health. Toxicol. Res. 2017, 33, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guimarães, A.C.; Meireles, L.M.; Lemos, M.F.; Guimarães, M.C.C.; Endringer, D.C.; Fronza, M.; Scherer, R. Antibacterial Activity of Terpenes and Terpenoids Present in Essential Oils. Molecules 2019, 24, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terpenes: A Source of Novel Antimicrobials, Applications and Recent Advances. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.1201/9781003243700-14/terpenes-source-novel-antimicrobials-applications-recent-advances-nawal-al-musayeib-amina-musarat-farah-maqsood (accessed on 6 June 2023).

- Mancuso, M.; Catalfamo, M.; Laganà, P.; Rappazzo, A.C.; Raymo, V.; Zampino, D.; Zaccone, R. Screening of antimicrobial activity of citrus essential oils against pathogenic bacteria and Candida strains. Flavour Fragr. J. 2019, 34, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paduch, R.; Kandefer-Szerszeń, M.; Trytek, M.; Fiedurek, J. Terpenes: Substances useful in human healthcare. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 2007, 55, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trindade, L.A.; de Araújo Oliveira, J.; de Castro, R.D.; de Oliveira Lima, E. Inhibition of adherence of C. albicans to dental implants and cover screws by Cymbopogon nardus essential oil and citronellal. Clin. Oral Investig. 2015, 19, 2223–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sil, A.; Pramanik, K.; Samantaray, P.; Mondal, F.; Yadav, V. Essential oils: A boon towards eco-friendly management of phytopathogenic fungi. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2020, 8, 1884–1891. [Google Scholar]

- Zengin, H.; Baysal, A.H. Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activity of Essential Oil Terpenes against Pathogenic and Spoilage-Forming Bacteria and Cell Structure-Activity Relationships Evaluated by SEM Microscopy. Molecules 2014, 19, 17773–17798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, Y.; Shiraishi, A.; Hada, T.; Hirose, K.; Hamashima, H.; Shimada, J. The antibacterial effects of terpene alcohols on Staphylococcus aureus and their mode of action. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2004, 237, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, H.; Ulrich-Merzenich, G. Synergy research: Approaching a new generation of phytopharmaceuticals. Phytomedicine Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2009, 16, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, J.-P. Research into the Mechanisms of Action of Biologically Active Molecules Derived from Natural Products. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Corse Pascal Paoli, Corte, France, 2018. Available online: https://www.theses.fr/2018CORT0017 (accessed on 6 June 2023).

- Bouank, H.; Kerouaz, M.; Bekka, F. (Encadreur) Study of the Antibacterial Activity of Essential Oils from Several Lamiaceae Species and the Effect of their Association with Antibiotics. Master’s Thesis, University of Jijel, Jijel, Algeria, 2016. Available online: http://dspace.univ-jijel.dz:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/8589 (accessed on 6 June 2023).

- Mahizan, N.A.; Yang, S.-K.; Moo, C.-L.; Song, A.A.-L.; Chong, C.-M.; Chong, C.-W.; Abushelaibi, A.; Lim, S.-H.E.; Lai, K.-S. Terpene Derivatives as a Potential Agent against Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Pathogens. Molecules 2019, 24, 2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adoui, M.; Lahouel, M. Characterization of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Strains and Assessment of their Sensitivity to Propolis. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Frères Mentouri—Constantine 1, Constantine, Algeria, 2019. Available online: http://depot.umc.edu.dz/handle/123456789/5096 (accessed on 6 June 2023).

- Han, Y.; Sun, Z.; Chen, W. Antimicrobial Susceptibility and Antibacterial Mechanism of Limonene against Listeria monocytogenes. Molecules 2019, 25, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.; Jeyakumar, E.; Lawrence, R. Strategic approach of multifaceted antibacterial mechanism of limonene traced in Escherichia coli. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambino, E.; Maione, A.; Guida, M.; Albarano, L.; Carraturo, F.; Galdiero, E.; Di Onofrio, V. Evaluation of the Pathogenic-Mixed Biofilm Formation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa/Staphylococcus aureus and Treatment with Limonene on Three Different Materials by a Dynamic Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seker, I.D.; Alacam, T.; Akca, G.; Yilmaz, A.; Takka, S. The antimicrobial effect of R-limonene and its nanoemulsion on Enterococcus faecalis—In vitro study. Preprint 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Chen, Y.-W.; Hou, C.-Y. Antioxidant and antibacterial activity of seven predominant terpenoids. Int. J. Food Prop. 2019, 22, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Eduardo, L.; Farias, T.C.; Ferreira, S.B.; Ferreira, P.B.; Lima, Z.N.; Ferreira, S.B. Antibacterial Activity and Time-kill Kinetics of Positive Enantiomer of α-pinene Against Strains of Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2018, 18, 917–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite-Sampaio, N.F.; Gondim, C.N.F.L.; Martins, R.A.A.; Siyadatpanah, A.; Norouzi, R.; Kim, B.; Sobral-Souza, C.E.; Gondim, G.E.C.; Ribeiro-Filho, J.; Coutinho, H.D.M. Potentiation of the Activity of Antibiotics against ATCC and MDR Bacterial Strains with (+)-α-Pinene and (−)-Borneol. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, e8217380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ProQuest. Antibacterial Efficacy of Thymol, Carvacrol, Eugenol and Menthol as Alternative Agents to Control the Growth of Nosocomial Infection-Bacteria. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/8dae1af2641433966a2b4dfa1b01570a/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=54977 (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Jahdkaran, E.; Hosseini, S.E.; Mohammadi Nafchi, A.; Nouri, L. The effects of methylcellulose coating containing carvacrol or menthol on the physicochemical, mechanical, and antimicrobial activity of polyethylene films. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 2768–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, R.; Zhang, D.; Wang, X.; Sun, R.; Guo, W.; Yang, S.; Li, H.; Gong, G. Antibacterial mechanism of thymol against Enterobacter sakazakii. Food Control 2021, 123, 107716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Huang, S.; Geng, Y.; Huang, X.; Chen, D.; Lai, W.; Guo, H.; Deng, H.; Fang, J.; Yin, L.; et al. A Study on the antibacterial mechanism of thymol against Aeromonas hydrophila in vitro. Aquac. Int. 2022, 30, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valliammai, A.; Selvaraj, A.; Yuvashree, U.; Aravindraja, C.; Karutha Pandian, S. sarA-Dependent Antibiofilm Activity of Thymol Enhances the Antibacterial Efficacy of Rifampicin Against Staphylococcus aureus. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta Felício, I.; Limongi de Souza, R.; de Oliveira Melo, C.; Gervázio Lima, K.Y.; Vasconcelos, U.; Olímpio de Moura, R.; Eleamen Oliveira, E. Development and characterization of a carvacrol nanoemulsion and evaluation of its antimicrobial activity against selected food-related pathogens. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 72, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechmechani, S.; Gharsallaoui, A.; Fadel, A.; Omari, K.E.; Khelissa, S.; Hamze, M.; Chihib, N.-E. Microencapsulation of carvacrol as an efficient tool to fight Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterococcus faecalis biofilms. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALrashidi, A.A.; Noumi, E.; Snoussi, M.; Feo, V.D. Chemical Composition, Antibacterial and Anti-Quorum Sensing Activities of Pimenta dioica L. Essential Oil and Its Major Compound (Eugenol) against Foodborne Pathogenic Bacteria. Plants 2022, 11, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.C.; Pereira, R.L.S.; de Freitas, T.S.; Rocha, J.E.; Macedo, N.S.; de Fatima Alves Nonato, C.; Linhares, M.L.; Tavares, D.S.A.; da Cunha, F.A.B.; Coutinho, H.D.M.; et al. Evaluation of antibacterial and toxicological activities of essential oil of Ocimum gratissimum L. and its major constituent Eugenol. Food Sci. 2022, 50, 102128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousnina, H.; Ghedeir ali, S. Literature Review on the Search for Local Bacterial Strains Producing Antimicrobial Substances in the Ouargla Region. Master’s Thesis, University of Kasdi Merbah Ouargla, Ouargla, Algeria, 2020. Available online: http://dspace.univ-ouargla.dz/jspui/handle/123456789/24951 (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Jose, J. Bioanalysis in medicinal chemistry: From assay development to evolutionary drug design. Ann. Pharm. Fr. 2009, 67, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Blum, S.E.; Barba-Behrens, N. Coordination chemistry of some biologically active ligands. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2000, 196, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, N.; Mislow, K. On chirality measures and chirality properties. Can. J. Chem. 2000, 78, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hentschel, M.; Schäferling, M.; Duan, X.; Giessen, H.; Liu, N. Chiral plasmonics. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1602735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrino, T.D.; de Medeiros, T.D.M.; Ruiz, A.L.T.G.; Favaro, D.C.; Pastore, G.M.; Bicas, J.L. Structural properties and evaluation of the antiproliferative activity of limonene-1,2-diol obtained by the fungal biotransformation of R-(+)- and S-(−)-limonene. Chirality 2022, 34, 887–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida Batista, S.A.; Vandresen, F.; Falzirolli, H.; Britta, E.; de Oliveira, D.N.; Catharino, R.R.; Gonçalves, M.A.; Ramalho, T.C.; La Porta, F.A.; Nakamura, C.V.; et al. Synthesis and comparison of antileishmanial and cytotoxic activities of S-(−)-limonene benzaldehyde thiosemicarbazones with their R-(+)-analogues. J. Mol. Struct. 2019, 1179, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, J.O.; Kumar, R.P.; Ma, A.C.; Patterson, M.; Krauss, I.J.; Oprian, D.D. Mechanism Underlying Anti-Markovnikov Addition in the Reaction of Pentalenene Synthase. Biochemistry 2020, 59, 3271–3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löser, P.S.; Rauthe, P.; Meier, M.A.R.; Llevot, A. Sustainable catalytic rearrangement of terpene-derived epoxides: Towards bio-based biscarbonyl monomers. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2020, 378, 20190267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malko, M.; Wróblewska, A. The importance of R-(+)-limonene as the raw material for organic syntheses and for organic industry. CHEMIK 2016, 70, 198–202. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Kamens, R.M. Particle nucleation from the reaction of α-pinene and O3. Atmos. Environ. 2005, 39, 6822–6832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- α-Pinene. Wikipedia. 30 July 2023. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=%CE%91-Pinene&oldid=1167931345 (accessed on 25 August 2023).

- Obafunmi, T.; Ocheme, J.; Gajere, B. Oligodynamic Effect of Precious Metals on Skin Bacteria. FUDMA J. Sci. 2020, 4, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, P.; Wang, W.; Duan, H.; Wang, Z. Synthesis, Characterization and Antimicrobial Studies of Ti-40Nb-10Ag Implant Biomaterials. Metals 2022, 12, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, R.J.C.; Hussain, A.A.; Sayer, M.; Vincent, P.J.; Hughes, D.J.; Smith, T.J.N. Antibacterial activity of multilayer silver–copper surface films on catheter material. Can. J. Microbiol. 1993, 39, 895–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, K.; Slay, B.; Knackstedt, M.; Gaharwar, A.K. Antimicrobial Activity of Metal and Metal-Oxide Based Nanoparticles. Adv. Ther. 2018, 1, 1700033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, A.; Cibik, S. The Evaluation of the Antibacterial Effect of Silver Anode Treatment on Raw Milk. SSRN 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhidime, I.D.; Saubade, F.; Benson, P.S.; Butler, J.A.; Olivier, S.; Kelly, P.; Verran, J.; Whitehead, K.A. The antimicrobial effect of metal substrates on food pathogens. Food Bioprod. Process. 2019, 113, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frei, A.; Verderosa, A.D.; Elliott, A.G.; Zuegg, J.; Blaskovich, M.A.T. Metals to combat antimicrobial resistance. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2023, 7, 202–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobman, J.L.; Crossman, L.C. Bacterial antimicrobial metal ion resistance. J. Med. Microbiol. 2015, 64, 471–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moustakas, M. The Role of Metal Ions in Biology, Biochemistry and Medicine. Materials 2021, 14, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aher, Y.; Jain, G.; Patil, G.; Savale, A.; Ghotekar, S.; Pore, D.; Pansambal, S.; Deshmukh, K. Biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using leaves extract of Leucaena leucocephala L. and their promising upshot against the selected human pathogens. Int. J. Mol. Clin. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 776–786. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnaraj, C.; Jagan, E.G.; Rajasekar, S.; Selvakumar, P.; Kalaichelvan, P.T.; Mohan, N. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Acalypha indica leaf extracts and its antibacterial activity against water borne pathogens. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2010, 76, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasser, G.; Metzler-Nolte, N. The potential of organometallic complexes in medicinal chemistry. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2012, 16, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, S.R.; Piccoli, P.M.B.; Schultz, A.J.; Todorova, T.K.; Gagliardi, L.; Girolami, G.S. Synthesis and Properties of a Fifteen-Coordinate Complex: The Thorium Aminodiboranate [Th(H3BNMe2BH3)4]. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 3379–3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, K.; Urbank, C.; Patzschke, M.; März, J.; Kaden, P.; Weiss, S.; Schmidt, M. MOFs with 12-Coordinate 5f-Block Metal Centers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 2879–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, R. Chirality in Biology. In Reviews in Cell Biology and Molecular Medicine; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-3-527-60090-8. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Yue, X.; Ding, Q.; Lin, H.; Xu, C.; Li, S. Chiral inorganic nanomaterials for biological applications. Nanoscale 2023, 15, 2541–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyakin, V.V. Fundamental Cause of Bio-Chirality: Space-Time Symmetry—Concept Review. Symmetry 2023, 15, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, P.S.S.; Lucchese, A.M.; Araújo-Filho, H.G.; Menezes, P.P.; Araújo, A.A.S.; Quintans-Júnior, L.J.; Quintans, J.S.S. Inclusion of terpenes in cyclodextrins: Preparation, characterization and pharmacological approaches. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 151, 965–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Matos, S.P.; Teixeira, H.F.; de Lima, Á.A.N.; Veiga-Junior, V.F.; Koester, L.S. Essential Oils and Isolated Terpenes in Nanosystems Designed for Topical Administration: A Review. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalevskaya, O.; Gur’eva, Y.; Kuchin, A. Terpene ligands in coordination chemistry: Synthesis of metal complexes, stereochemistry, catalytic properties, biological activity. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2019, 88, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frei, A.; Zuegg, J.; Elliott, A.G.; Baker, M.; Braese, S.; Brown, C.; Chen, F.; Dowson, C.G.; Dujardin, G.; Jung, N.; et al. Metal complexes as a promising source for new antibiotics. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 2627–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudel, M.; Schwarte, J.V.; Fromm, K.M. New Antimicrobial Strategies Based on Metal Complexes. Chemistry 2020, 2, 849–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Yang, X.; He, J.; Cai, S.; Xiao, K.; Zhu, L. Enhanced antioxidant activity, antibacterial activity and hypoglycemic effect of luteolin by complexation with manganese(II) and its inhibition kinetics on xanthine oxidase. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 53385–53395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, D.; Joo, S.-W.; Shinde, V.V.; Cho, E.; Jung, S. Carbohydrate-Based Host-Guest Complexation of Hydrophobic Antibiotics for the Enhancement of Antibacterial Activity. Molecules 2017, 22, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollo, G.; Corre, P.L.; Chollet, M.; Chevanne, F.; Bertault, M.; Burgot, J.; Verge, R.L. Improvement in solubility and dissolution rate of 1,2-dithiole-3-thiones upon complexation with β-cyclodextrin and its hydroxypropyl and sulfobutyl ether-7 derivatives. J. Pharm. Sci. 1999, 88, 889–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möhler, J.S.; Kolmar, T.; Synnatschke, K.; Hergert, M.; Wilson, L.A.; Ramu, S.; Elliott, A.G.; Blaskovich, M.A.T.; Sidjabat, H.E.; Paterson, D.L.; et al. Enhancement of antibiotic-activity through complexation with metal ions—Combined ITC, NMR, enzymatic and biological studies. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2017, 167, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naureen, B.; Miana, G.A.; Shahid, K.; Asghar, M.; Tanveer, S.; Sarwar, A. Iron (III) and zinc (II) monodentate Schiff base metal complexes: Synthesis, characterisation and biological activities. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1231, 129946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, N.; Buldurun, K.; Adiguzel, R.; Aras, A.; Turkan, F.; Bursal, E. Investigation of spectroscopic, thermal, and biological properties of FeII, CoII, ZnII, and RuII complexes derived from azo dye ligand. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1244, 130989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rundstadler, T.K.; Eskandari, A.; Norman, S.M.; Suntharalingam, K. Polypyridyl Zinc(II)-Indomethacin Complexes with Potent Anti-Breast Cancer Stem Cell Activity. Molecules 2018, 23, 2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakr, S.H.; Elshafie, H.S.; Camele, I.; Sadeek, S.A. Synthesis, Spectroscopic, and Biological Studies of Mixed Ligand Complexes of Gemifloxacin and Glycine with Zn(II), Sn(II), and Ce(III). Molecules 2018, 23, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draoui, Y.; Radi, S.; Tanan, A.; Oulmidi, A.; Miras, H.N.; Benabbes, R.; Ouahhoudo, S.; Mamri, S.; Rotaru, A.; Garcia, Y. Novel family of bis-pyrazole coordination complexes as potent antibacterial and antifungal agents. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 17755–17764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oulmidi, A.; Radi, S.; Idir, A.; Zyad, A.; Kabach, I.; Nhiri, M.; Robeyns, K.; Rotaru, A.; Garcia, Y. Synthesis and cytotoxicity against tumor cells of pincer N-heterocyclic ligands and their transition metal complexes. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 34742–34753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fandzloch, M.; Jaromin, A.; Zaremba-Czogalla, M.; Wojtczak, A.; Lewińska, A.; Sitkowski, J.; Wiśniewska, J.; Łakomska, I.; Gubernator, J. Nanoencapsulation of a ruthenium(II) complex with triazolopyrimidine in liposomes as a tool for improving its anticancer activity against melanoma cell lines. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 1207–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Hoff, D.D.; Rozencweig, M. cis-Diamminedichloroplatinum (II): A Metal Complex with Significant Anticancer Activity. In Advances in Pharmacology; Garattini, S., Goldin, A., Hawking, F., Kopin, I.J., Schnitzer, R.J., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979; Volume 16, pp. 273–298. [Google Scholar]

- Zehra, S.; Gómez-Ruiz, S.; Siddique, H.R.; Tabassum, S.; Arjmand, F. Water soluble ionic Co(II), Cu(II) and Zn(II) diimine–glycinate complexes targeted to tRNA: Structural description, in vitro comparative binding, cleavage and cytotoxic studies towards chemoresistant prostate cancer cells. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 16830–16848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senthilkumar, G.; Sankarganesh, M.; Raja, D.; Jose, P.A.; Sakthivel, A.; Christopher, T.; Asha, R.N.; Raj, P.; Christopher Jeyakumar, T. Water soluble Cu(II) and Zn(II) complexes of bidentate-morpholine based ligand: Synthesis, spectral, DFT calculation, biological activities and molecular docking studies. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 40, 1074–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shwiniy, W.H.; Abbass, L.M.; Sadeek, S.A.; Zordok, W.A. Synthesis, Structure, and Biological Activity of Some Transition Metal Complexes with the Mixed Ligand of Metformin and 1,4-Diacetylbenzene. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2020, 90, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Dief, A.M.; Abdel-Rahman, L.H.; Abdelhamid, A.A.; Marzouk, A.A.; Shehata, M.R.; Bakheet, M.A.; Almaghrabi, O.A.; Nafady, A. Synthesis and characterization of new Cr(III), Fe(III) and Cu(II) complexes incorporating multi-substituted aryl imidazole ligand: Structural, DFT, DNA binding, and biological implications. Spectrochim. Acta. A. Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020, 228, 117700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soayed, A.A.; Refaat, H.M.; Noor El-Din, D.A. Metal complexes of moxifloxacin–imidazole mixed ligands: Characterization and biological studies. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2013, 406, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcillo-Parra, V.; Tupuna-Yerovi, D.S.; González, Z.; Ruales, J. Encapsulation of bioactive compounds from fruit and vegetable by-products for food application—A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 116, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, N.; Meghwal, M.; Das, K. Microencapsulation: An overview on concepts, methods, properties and applications in foods. Food Front. 2021, 2, 426–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñón-Balderrama, C.I.; Leyva-Porras, C.; Terán-Figueroa, Y.; Espinosa-Solís, V.; Álvarez-Salas, C.; Saavedra-Leos, M.Z. Encapsulation of Active Ingredients in Food Industry by Spray-Drying and Nano Spray-Drying Technologies. Processes 2020, 8, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, M.R.; Veena, N.; Watharkar, R.B. Novel Processing Methods for Plant-Based Health Foods: Extraction, Encapsulation, and Health Benefits of Bioactive Compounds; Apple Academic Press: Palm Bay, FL, USA, 2023; ISBN 9781774910740. [Google Scholar]

- Halahlah, A.; Piironen, V.; Mikkonen, K.S.; Ho, T.M. Polysaccharides as wall materials in spray-dried microencapsulation of bioactive compounds: Physicochemical properties and characterization. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.A.; Ellenberger, D.; Porfirio, T.; Gil, M. Spray-Drying Technology. In Formulating Poorly Water Soluble Drugs; Williams, R.O., III, Davis, D.A., Jr., Miller, D.A., Eds.; AAPS Advances in the Pharmaceutical Sciences Series; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 377–452. ISBN 978-3-030-88719-3. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, G.G.; Guterres, K.B.; Bonez, P.C.; da Silva Gundel, S.; Aggertt, V.A.; Siqueira, F.S.; Ourique, A.F.; Wagnerd, R.; Klein, B.; Santos, R.C.V.; et al. Antibiofilm activity of nanoemulsions of Cymbopogon flexuosus against rapidly growing mycobacteria. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 113, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciamponi, F.; Duckham, C.; Tirelli, N. Yeast cells as microcapsules. Analytical tools and process variables in the encapsulation of hydrophobes in S. cerevisiae. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 95, 1445–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donsì, F.; Annunziata, M.; Sessa, M.; Ferrari, G. Nanoencapsulation of essential oils to enhance their antimicrobial activity in foods. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 44, 1908–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ré, M.I. Microencapsulation by Spray Drying. Dry. Technol. 1998, 16, 1195–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Luo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Zhou, B.; Liu, H. Ginger essential oil-based microencapsulation as an efficient delivery system for the improvement of Jujube (Ziziphus jujuba Mill.) fruit quality. Food Chem. 2020, 306, 125628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chasquibol, N.; Gonzales, B.F.; Alarcón, R.; Sotelo, A.; Gallardo, G.; García, B.; Pérez-Camino, M. del C. Co-Microencapsulation of Sacha Inchi (Plukenetia huayllabambana) Oil with Natural Antioxidants Extracts. Foods 2023, 12, 2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carneiro, H.C.F.; Tonon, R.V.; Grosso, C.R.F.; Hubinger, M.D. Encapsulation efficiency and oxidative stability of flaxseed oil microencapsulated by spray drying using different combinations of wall materials. J. Food Eng. 2013, 115, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zhang, M.; Adhikari, B.; Wang, M. Microencapsulation of Sichuan pepper essential oil in soybean protein isolate-Sichuan pepper seed soluble dietary fiber complex coacervates. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 125, 107421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, G.A.; Fávaro-Trindade, C.S.; Grosso, C.R.F. Microencapsulation of lycopene by spray drying: Characterization, stability and application of microcapsules. Food Bioprod. Process. 2012, 90, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujur, A.; Kiran, S.; Dubey, N.K.; Prakash, B. Microencapsulation of Gaultheria procumbens essential oil using chitosan-cinnamic acid microgel: Improvement of antimicrobial activity, stability and mode of action. LWT 2017, 86, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Hernández, E.; Regalado-González, C.; Vázquez-Landaverde, P.; Guerrero-Legarreta, I.; García-Almendárez, B.E. Microencapsulation, Chemical Characterization, and Antimicrobial Activity of Mexican (Lippia graveolens H.B.K.) and European (Origanum vulgare L.) Oregano Essential Oils. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, e641814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arana-Sánchez, A.; Estarrón-Espinosa, M.; Obledo-Vázquez, E.N.; Padilla-Camberos, E.; Silva-Vázquez, R.; Lugo-Cervantes, E. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Mexican oregano essential oils (Lippia graveolens H. B. K.) with different composition when microencapsulated inβ-cyclodextrin. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 50, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarda, A.; Rubilar, J.F.; Miltz, J.; Galotto, M.J. The antimicrobial activity of microencapsulated thymol and carvacrol. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 146, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetta, A.; Kegere, J.; Mamdouh, W. Comparative study of encapsulated peppermint and green tea essential oils in chitosan nanoparticles: Encapsulation, thermal stability, in-vitro release, antioxidant and antibacterial activities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 126, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asensio, C.; Paredes, A.; Martin, M.; Allemandi, D.; Nepote, V.; Grosso, N. Antioxidant Stability Study of Oregano Essential Oil Microcapsules Prepared by Spray-Drying. J. Food Sci. 2017, 82, 2864–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Healthcare-Associated Infection Types | Microorganisms | References |

|---|---|---|

| Central line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) | Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase-negative staphylococci, Candida spp., methicillin-resistant Staphylococci (MRSA), Enterococci, Klebsiella, Enterobacter, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, Acinetobacter, and Candida species | [44,45,46,47,48,49] |

| CVC/hemodialysis catheter infection | Enterobacter cloacae complex (ECC), Candida parapsilosis, Staphylococcus aureus, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) | [50,51,52] |

| Pediatric ventilator-associated events (PedVAEs) | Candida albicans, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Haemophilus infuenzae | [53,54,55,56,57,58] |

| Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Enterobacterales | [59,60,61] |

| Catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI) | Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterococcus faecalis, and Candida | [62,63,64,65,66] |

| Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) infection | Streptococcus and Staphylococcus aureus | [67,68,69,70,71,72,73] |

| Cardiovascular devices | Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, and Staphylococcus aureus | [74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82] |

| Surgical site infection (SSI) | Escherichia coli, Enterobacter spp., Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus spp., Klebsiella pneumoniae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterococcus faecalis, Proteus spp., and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) CoNS | [83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90] |

| Prosthetic joint infection (PJI) | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus, Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus lugdunensis, Staphylococcus spp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Streptococcus gordonii | [91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101] |

| Foodborne Pathogen | Food Environment Processes | Food Equipment Isolation | Food Product | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Listeria spp. | Fine cutting of loin | Apron Conveyor belt Loin ripping board | Meat | [114] |

| Packaging film Hooks | ||||

| Meat cutting | Saw Conveyor belt | |||

| Drains Floors Freezers Aprons Door handles Taps | Smoked salmon Raw salmon | [115] | ||

| Knives Mincing machine Deriding machine Bowl cutter Vacuum packaging machine Slicing machine Scales Stainless-steel tables Sticks for hanging the products Cutting boards Stainless steel trolley | Pork, beef, chicken, and sheep meat | [116] | ||

| Mushroom | [117] | |||

| Iceberg lettuce | [118] | |||

| Poultry meat Raw beef | [119] | |||

| Chicken cold cuts | [120] | |||

| Cold storage | Pork meat | [121] | ||

| 3D Food Printing Systems | Food ink capsules | [122] | ||

| Bulk tank milk Milk filter | Raw milk | [123] | ||

| Fish processing plants | [124] | |||

| Food service establishments | Enoki mushrooms | [125] | ||

| Cutting room | Meat | [126] | ||

| Floor Mixing trough Separating machines Cutter Transport belt Mixing machine Dicing machine Knives | Saucisse Saucisson Rosette Chorizo | [127] | ||

| Escherichia coli | Sliced cooked and cured ham Sliced cooked and cured sausage Sliced cooked meats Veal pie and calf liver pâté | [128] | ||

| Refrigerated storage | Kale | [129] | ||

| Fresh beef | [130] | |||

| Countertop Draining board | Chicken | [131] | ||

| Staphylococcus spp. | Milk | [132,133] | ||

| Pastries Cereals | [134] | |||

| Quail breast | [135] | |||

| Kazak cheese | [136] | |||

| Dairy farms | Hand Bulk farm milk Pooled udder milk Milking container Bulk container Teat Overall | Milk Water for cleaning teat and hands | [137] | |

| Dish cloth Hands Refrigerator handle Oven handle Countertop Draining board | Chicken | [131] | ||

| Slaughter hall cutting room | Meat | [126] | ||

| Dairy staff | Hands Anterior nares | Raw milk Minas Frescal cheese Food handlers | [138] | |

| Salmonella spp. | Chicken breeds | [139] | ||

| Pet food | [140] | |||

| Plastic (tote) Plastic (bucket elevator) Stainless steel Concrete Rubber (belt) Rubber (tire) | [141] | |||

| Domestic kitchen surfaces | - | Chicken carcasses | [142] | |

| Tomatoes | [143] | |||

| Individual production chains | Poultry food Chicken gizzards | [144] | ||

| 3D food printing systems | Food ink capsules | [122] | ||

| Bulk tank milk Milk filter | Raw milk | [123] | ||

| Fresh beef | [130] | |||

| Dish cloth Countertop | Chicken | [131] |

| EPS Elements | Role |

|---|---|

| Polycarbohydrates, proteins, and DNA | Adhesion |

| Neutral and charged polycarbohydrates, proteins (such as amyloids and lectins), and DNA | Cohesion |

| Polycarbohydrates and proteins | Barrier of defense |

| Potentially all the components of EPS * | Source of nutrients |

| Hydrophilic polycarbohydrates and eventually proteins | Water retention |

| Extracellular DNA | Genetic information exchange |

| Metal | Ligand | Activity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ru (II) | Based on limonene | Antibacterial Anticancer | [21] |

| Zn (II) Fe (III) | Monodentate Schiff base | Antifungal Antioxidant Antibacterial | [241] |