Abstract

The objective was to assess physical exercise programs (individualized and group) targeting postural correction in Parkinson’s disease patients. A total of 29 Parkinson’s disease patients performed an individualized (12 patients) or group exercise program (17 patients) for 6 months. After 6 months of therapy, all patients received a self-made questionnaire that assessed the benefits of exercise programs for their health status and the compliance to therapy. Patients also completed the Movement Disorder Society–Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) questionnaire (patients’ section) at the inclusion in the study and after 6 months. All patients considered that the physical exercise program had benefits and was important for their functioning and health status. There were no significant differences in what concerns the mental and physical status during the physical exercise program, and the improvement in quality of life after physical exercise program in the two groups. After the 6 month physical exercise program, a significantly improved functional status was recorded in both groups (MDS-UPDRS scores for individualized therapy: 1.90 ± 1.05 vs. 2.30 ± 1.04, p = 0.001; for group therapy: 1.79 ± 0.85 vs. 2.13 ± 1.02, p = 0.005). The proposed questionnaire for assessment of physical exercise programs for patients with Parkinson’s disease represents a valuable and easy-to-use tool.

1. Introduction

Parkinson’s disease is the second most frequent neurodegenerative disease after Alzheimer dementia. After stroke, it is the second most common cause of motor disability in elderly people. Parkinson’s disease affects 1% to 2% of the global population. Incidence rate is estimated to 20 at 100,000 persons; prevalence is 150 at 100,000 persons [1]. The disease appears when the grey matter from the brain and spinal cord diminishes and the nervous cells that control a body area affects the movement while not receiving a normal command for a certain action [1,2]. When Parkinson’s disease appears, between 70–80% of the cells that produce dopamine are deteriorated or destroyed and the messages to the musculature are not transmitted correctly [3]. Thus, the patients’ activities and actions are hindered; instability, loss of the center of gravity, fine movement disorders and, in the case of younger people with Parkinson’s disease, even professional retirement are the disease consequences [4]. If there is insufficient dopamine, nerve cells cannot function correctly and transmit messages from the brain. Symptoms frequently appear insidious; however, progressive disease is present. Motor symptoms contribute to positive diagnosis; tremor, rigidity (in 80% of the patients), bradykinesia, and postural instability are common. All these symptoms contribute to postural changes [5,6]. Moreover, in Parkinson’s disease, the non-motor symptoms that appear before the motor ones are equally present. They contribute to alteration of the physical and emotional status of the patients due to fatigue, excessive diaphoresis, hypersalivation, alteration of the voice tone, anosmia, and frequent enuresis. Patients can experience confusion, anxiety, or depression [7].

The specific posture of the patients with Parkinson’s disease results from the loss of postural reflexes, decrease in muscle function through excessive rigidity, and reduced mobility. A particular feature in patients suffering from Parkinson’s disease can be noticed kyphosis, anteriorly bent shoulders, semi-flexed elbows, and semi-flexed knees. These distinct postures produce a muscle imbalance, changes during standing and walking, contributing, thus, to frequent falls and limitations in activities of daily living [5,7,8,9]. The severity of postural deformities was associated with a lower age-controlled standardized behavioral assessment of the dysexecutive syndrome score and executive dysfunction [10].

Exercise is an essential component in the overall management of patients with Parkinson’s disease [11]. López-Liria et al. [12] pointed out that the studies included in their systematic review considered that specific trunk exercises (for improvement of trunk mobility, trunk strengthening, or central stabilization) and balance training should be a complement to pharmacological treatment for improving balance and postural instability in Parkinson’s disease patients. The study of Gandolfi et al. [13] showed that the four-week trunk-specific rehabilitation training (consisting of active self-correction exercises with visual and proprioceptive feedback, passive and active trunk stabilization exercises, and functional tasks) decreased the forward trunk flexion severity and increased postural control in this category of patients. Yitayeh and Teshome in their review [14] state that muscle strengthening, range of movement exercises, and balance training have comparable outcomes for balance and postural stability.

The main objective of the current pilot study was to assess the physical exercise programs (individualized and group program) targeting the postural correction in Parkinson’s disease patients. The envisaged outcomes of the physical exercise programs were the improvements in the physical and mental status, and quality of life. The assessment implied the use of a self-made questionnaire and of a standardized tool (Movement Disorder Society–Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale). The motivation for investigating the outcomes of 6 month rehabilitation for posture improvement is the fact that postural control, balance, and stability are essential for this category of patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Patients suffering from Parkinson’s disease took part in the study. They were included in physical exercise programs in day care social integration/reintegration for people in difficulty. The participants started physical exercise one to five years from the diagnosis; they also followed a specialty medical treatment as recommended by the neurologist. The substance and dose vary depending on symptoms, age, associated pathologies, and the therapeutic response. The medical treatment is administered orally and transdermically at recommended hours. The treatments of the patients are from levodopa class, dopaminergic agonists, B-monoaminooxidase inhibitors, and dopa-decarboxidrase inhibitors.

The inclusion criteria were patients diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease under medical treatment. The exclusion criteria were the following: stage 4 or 5 of Parkinson’s disease (according to the Hoehn and Yahr scale [15]), other neurological disorders (stroke, etc.), ankylosing spondylitis, and psychiatric disorders.

A total of 29 patients (55% men and 45% women) diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease were included in the study. Patients’ characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Parkinson’s disease patients.

2.2. Physical Exercise Programs

The physical exercise program was either individualized or performed as a group therapy. In the individualized program, the patients received a series of exercises for the correction of posture and body alignment. In the group program, the participants performed exercises in pairs (two or more participants) using different objects (balls, canes, dumbbells, elastic bands). The patients were asked before the group inclusion what type of program they were willing to participate. At the beginning, they took part in the individualized program and afterwards in the group therapy. After both experiences, each patient chose a type of therapy.

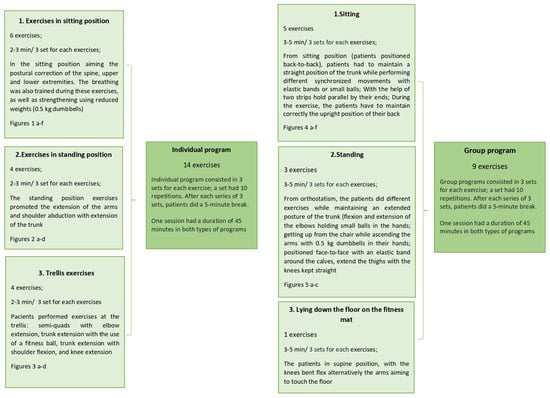

The frequency and intensity of exercises were established after the evaluation of the effort capacity. Both programs consisted of 3 sets for each exercise; a set had 10 repetitions. After each series of 3 sets, patients had a 5 min break. The exercises were of a moderate level of intensity in order to avoid overload and fatigue. At the end of the program, the patients performed stretching for relaxation. The exercises were diverse, with emphasize on those for postural correction. Stability, ability, force, and mobility exercises were also included. One session had a duration of 45 min in both types of programs (individual or group program). The frequency of sessions depended on the patients’ availability and physical status. All the participants participated in the physical exercise programs one, twice, or three times per week.

The exercises aimed to correct the posture and to increase range-of-motion of the upper and lower limbs joints. With the help of dumbbells, bands, and weights, the muscle strengthening was also obtained, thus, improving the upright posture. The exercises performed in standing position increased stability and ability while standing and walking. The exercises with the fitness ball and from the supine position promoted mobility through stretching.

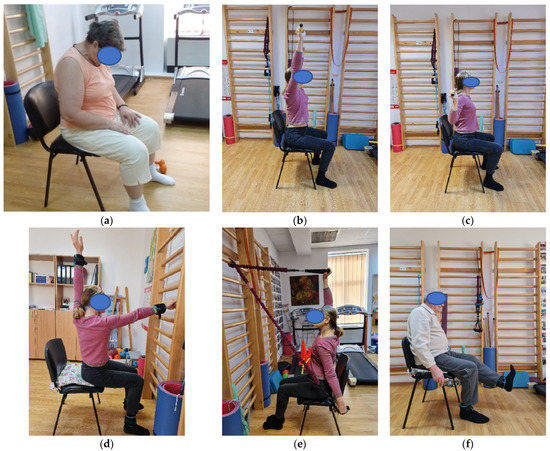

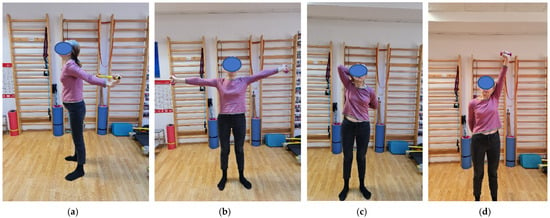

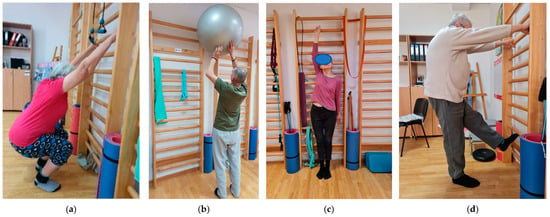

For the individualized program, the exercises started with those in the sitting position, aiming the postural correction of the spine, and upper and lower extremities. The breathing was also trained during these exercises, as well as muscle strengthening using low weights (0.5 kg dumbbells) (Figure 1a–f). The exercises in standing position promoted the extension of the arms and shoulder abduction with extension of the trunk (Figure 2a–d). Patients also performed exercises at the trellis (semi-quads with elbow extension, trunk extension with the use of a fitness ball, trunk extension with shoulder flexion, and knee extension) (Figure 3a–d).

Figure 1.

(a–f) Individual program: exercises in sitting position (flexion and extension of the cervical spine, flexion, and extension of the shoulders with trunk extension, knee extension).

Figure 2.

(a–d) Individual program: exercises in standing position (extension, abduction and rotations of the shoulders with trunk extension).

Figure 3.

(a–d) Individual program: trellis exercises (semi-quads, shoulder flexion with trunk extension, knee extension).

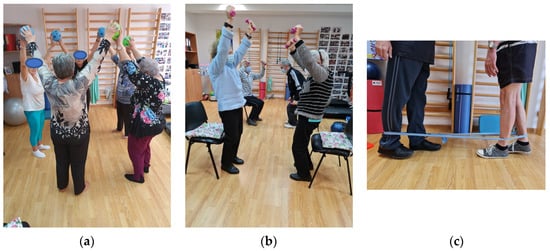

For the group program, the exercises were performed in different positions (sitting, standing, and lying down on the fitness mat). In the sitting position (patients positioned back-to-back), patients had to maintain a straight position of the trunk while performing different synchronized movements with elastic bands or small balls (Figure 4a–c). The two partners positioned face-to-face, with a fitness ball between them, performed forward bending of the trunk (Figure 4d). With the help of two strips hold parallel by their ends, the therapist placed a ball on the strips and the partners had to incline the ball from one to another in order to make it move without falling down. During these exercises, the patients had to correctly maintain the upright position of the trunk (Figure 4e). In Figure 4f, the patients, holding two sticks, raised the arms with inhalation, maintained the position for 5–8 s, and then lowered the arms with exhalation. While standing, the patients performed different exercises while maintaining an extended posture of the trunk (flexion and extension of the elbows holding small balls in the hands; getting up from the chair while ascending the arms with 0.5 kg dumbbells in their hands; positioned face-to-face with an elastic band around inferior part of the calves, extended the thighs with the knees kept straight) (Figure 5a–c). The patients in supine position, with the knees bent, flexed their arms alternatively, aiming to touch the floor.

Figure 4.

(a–f) Group program: exercises in sitting position (shoulder range of motion exercises and strengthening exercises with trunk extension).

Figure 5.

(a–c) Group program: exercises in standing position (shoulder range of motion exercises and strengthening exercises with trunk extension, stability exercise).

The two types of exercise programs are systematically presented as a flow chart (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Flow chart of the individual and group programs.

2.3. Assessment

For assessment, 6 months after performing either individual or group exercise program, all patients received a self-made questionnaire (designed by the authors) consisting of 14 questions. The questionnaire addressed the following items: period of time the patient benefitted from physical exercise program; frequency of participation in the physical exercise program; difficulty level of the physical exercise program; mental status during the physical exercise program; physical status during the physical exercise program; information about the type of exercises (if they were clearly explained by the physical therapist); benefits after performing the physical exercise program; change in the quality of life after performing the physical exercise program; self-esteem; necessity of continuing the exercises at home; persistence in performing the exercises at home; level of satisfaction with the physical exercise program; type of therapy most appropriate for the patient; and if the patient followed the instructions of the physical therapist during the physical exercise program. The scores for the difficulty level of the physical exercise program were rated from 1 (no difficulty) to 4 (unable to complete). The mental and physical status during the physical exercise program were scored from 1 (very good) to 4 (worse). The scores for improvement in the quality of life after physical exercise program ranged between 1 (significant improvement) to 4 (worsening).

Patients also completed the Movement Disorder Society–Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) questionnaire (the section for patients) at the inclusion in the study and after 6 months. This section assesses the following: non-motor aspects of the physical activity—pain and other sensations; motor aspects of daily activities—hygiene, hobbies, and other activities, getting out of bed, a car, or a deep chair, gait and balance; and motor examination—postural stability. These items were included in the analysis after the patients’ clinical examination. These specific items were taken into consideration as they related to overall functioning. Each item had a score ranging from 0 (normal) to 4 (severely affected) [16].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The data were processed in SPSS Statistics 23.0. Descriptive statistics were calculated for patients’ characteristics (mean and standard deviation). The sample size for the pilot study was considered to be at least 9% of the main trial sample size [17]. The main trial sample size was calculated on the basis of results of Min-Jae and Dae-Sung using G*Power 3.1.9.7 (Universitat Kiel, Kiel, Germany). The effect size was 0.5, the type I error was α = 0.05, and power was 0.95. A total sample size of the pilot study of 16 patients was required, 8 patients for each group.

Parametric tests were used as the data had a normal distribution. The normality of continuous data were tested by D’Agostino skewness test and Anscombe–Glynn kurtosis test. The t-test was used for intergroup and intragroup comparisons. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Over half of the participants are, according to the Hoehn and Yahr standardization [15], in stage 3 of the disease. Patients have bilateral symptoms that involve the extremities. They have difficulties in maintaining balance during standing and walking, as well when going upstairs and downstairs.

The results of the questionnaire are included in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of the questionnaire assessment.

A total of 68% of patients have been previously involved in an exercise program for Parkinson’s disease (not focusing on postural correction). Almost half patients believe the program is not difficult or of a mild difficulty. A small percentage (4 out of 29 patients) are not able to complete the entire program.

Most of the patients (24 out of 29) consider that they have obtained from the physical therapist the necessary information about the exercises. A total of 25 patients (86%) follow the physical therapist’s instructions during the physical exercise program. A total of 85% of patients are very satisfied with their physical therapist. They appreciate the respect, collaboration, openness, and availability of the physical therapist. All patients express the same opinion about the physical therapist’s capacity of listening to them, of empathizing, and understanding their problems.

All the patients consider that the physical exercise program brings benefits and is important for their functioning and health status. After performing a physical exercise program, patients describe an improved functionality and feeling more secure when performing the activities of daily living. They are more confident; however, the lack of activity in an organized framework could be a factor for discontinuing the exercises at home. In the current study, 45% of patients do not continue the recommended physical exercise program at home. Only 31% are persistent in performing the exercises at home; 24% occasionally (once per week) perform the recommended program.

There are no significant differences in what concerns the mental and physical status during the physical exercise program, and the improvement in the quality of life after physical exercise program in the two groups (individual therapy versus group therapy) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Group comparison of the influence of physical exercise programs on health status of Parkinson’s disease patients.

Table 4 includes the MDS-UPDRS scores of each of the assessed items (for all the patients). The higher scores of the MDS-UPDRS reflect a strongly changed/severe functional status (the effects of the symptoms are clear to a great extent), and the lower scores reflect a normal functionality with a mild change in the functional status. The MDS-UPDRS (the combined score of the seven assessed items) improves significantly after the 6 month physical exercise program (initial assessment 2.20 ± 1.01; 6-month assessment 1.83 ± 0.92; p = 0.001). When assessing the intragroup MDS-UPDRS (the combined score), there are statistically significant improvements for both groups after 6 months of the exercise program (Table 5).

Table 4.

MDS-UPDRS scores at first assessment and after 6 months (all patients included).

Table 5.

MDS-UPDRS scores at first assessment and after 6 months for each group.

4. Discussion

In the current study, we aimed to point out the importance of long-term rehabilitation (6 months) for overall functioning in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Two different types of physical exercise programs (individualized and group program) were assessed. The sequences of exercises and the adaptations to Parkinson’s disease patients were proposed by the authors. The patients were assessed in terms of benefits of the exercise programs and compliance to therapy.

The patients’ compliance to physical exercise programs is extremely important for achieving the best rehabilitation outcomes. This has to be taken into account when establishing the objectives and the most appropriate physical therapy. The study of Borrero et al. [18] emphasized the importance of patients’ exercise history when making recommendations for physical activity. The group-based exercise was crucial for adherence and motivation in those without a strong history of participation in exercise prior to Parkinson’s disease diagnosis.

Two randomized controlled trials proved an attenuation of motor symptoms measured in the off-medication state in patients who had performed high-intensity aerobic exercise [19,20]. These studies pointed out that a sufficient dose of exercise together with a good compliance to exercise are important. The review of Schootemeijer et al. [21] states that long-term compliance is crucial for patients’ expectations, including the hope that extended engagement in regular exercise might help to change the progression of Parkinson’s disease.

In our pilot study, a questionnaire was used to identify what type of therapy was suitable and more efficient for the patient. This implies compliance to a certain type of therapy. The physical therapist also has an important role in transmitting the information requested by the patient about physical exercise influence on the disease progression. By using this self-made instrument, the perception of the patient about the physical exercise program was targeted, and if the patient considered the therapy important for the physical and mental health. After analyzing the answers of the questionnaire, the physical therapist can engage the patient in the most appropriate therapy, and modify the intensity and difficulty of the physical exercise program. The questionnaire is easy to complete; it takes a maximum of 5 minutes.

Multidisciplinary approaches in neurodegenerative diseases represent a modern concept, justified by the final therapeutic objective of every single patient with a chronic disease [2]. The guideline of Zippenfening [2] points out the particularities of different practical aspects of individualized and group therapy, and shows the importance of physical exercise programs for postural correction. The same author applied these programs in the current study, with a special target on assessing the Parkinson’s disease patients’ compliance to exercise.

David and Russel [22] showed the role of group therapies in Parkinson’s disease. The way patients again feel the sense of normality offers them more security and motivates them to take part in other community events. This last aspect encourages the patient to socialize, to share life experiences in order to tackle the symptoms differently, and to perform activities with people suffering from the same disease. In our study, there is a slightly higher preference for the group therapy. A total of 59% of patients prefer group therapy versus 41% who prefer individual therapy.

The role of compliance questionnaires assessing the physical exercise programs is extremely important, as this tool helps to understand the perception of the patient in relation to rehabilitation [23]. By using the self-made questionnaire, we also obtained relevant data related to the difficulty level of the physical exercise program, benefits for the health status, and improvement in the quality of life after the physical exercise program. Persistence in performing the exercises at home and continuation of the recommended physical exercise program at home are features related to patients’ compliance.

Regarding the analysis of functionality through the interview method, after filling in the MDS-UPDRS questionnaire, Sangarapillai et al. [24] evaluated the disease management and the severity grade of the motor symptoms. This scale brings important data about the way symptoms affect the patient’s physical state and shows the particularities of the disease progression. The study of Lo et al. [25] combined MDS-UPDRS with Purdue pegboard test to offer a greater sensitivity in detecting the motor changes in Parkinson’s disease. In our research, we chose to combine MDS-UPDRS with a questionnaire in order to assess the patients’ perception on the physical exercise programs in relation to overall functionality. The review of Mak et al. [26] states that clinically meaningful improvements in UPDRS-III scores are obtained after a training period longer than 12 weeks. Our study showed significant improvements of MDS-UPDRS scores after 6 months of exercise programs.

The small sample size and the fact that the two therapy groups were unequal are limitations of our study. The lack of validation of the self-made questionnaire can be considered a weak point of the current research. However, we consider this study as a pilot one and we aim to continue the assessment of longer term physical exercise programs (one year after the start of physical exercise programs). The implications of the current study are related to rehabilitation importance for postural correction in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Our intention was not to make a comparison between the two exercise programs, but to point out their benefits for this category of patients. The present study is the starting point for future directions of our research with the inclusion of a higher number of patients and the validation of the proposed questionnaire. We also aim to include an objective posture analysis (for example, using the GaitOn posture analysis system) for patients with Parkinson’s disease that have followed different physical exercise programs.

5. Conclusions

The proposed questionnaire for assessment of physical exercise programs in patients with Parkinson’s disease represents a valuable and easy-to-use tool. According to their preferences, the patients in our study followed either the individual or group program. The data collected helped the physical therapist in adapting the physical exercise programs to patients’ needs and objectives. Moreover, the questionnaire analysis offered information about the patients’ perception of the difficulties in performing the physical exercises, as well as the awareness of the role of physical exercise in the management of Parkinson’s disease. After a 6 month physical exercise program (either individual or group type), all patients had a significantly improved functional status.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.A.Z. and E.A.; methodology, H.A.Z.; formal analysis, M.R.R.; investigation, H.A.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, H.A.Z.; writing—review and editing, H.A.Z., E.A. and M.R.R.; visualization, E.A. and M.R.R.; supervision, E.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

In conformity with the ethical standards, the participation at this study was voluntary, and the patients were informed of the procedure of testing. All the participants at this study consented in writing for the work of data and utilizing them scientifically. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of “Victor Babes” University of Medicine and Pharmacy Timișoara, Romania (No. 49/15 September 2022) and it is in conformity with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Supplementary data available at request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jagadeesan, A.J.; Murugesan, R. Currents trends in etiology, prognosis and therapeutic aspects of Parkinson’s disease: A review. Acta Bio Medica Atenei Parm. 2017, 88, 249–262. [Google Scholar]

- Zippenfening, H.A.; Alexoi, I. Kinetoterapie și Nutriție Destinată Bolii Parkinson GHID; Mirton: Timișoara, Romania, 2021; pp. 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- The Michael, J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. Available online: https://www.michaeljfox.org/parkinsons-101 (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Foster, E.R.; Carson, L.G.; Archer, J.; Hunter, E.G. Occupational Therapy Interventions for Instrumental Activities of Daily Living for Adults with Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2021, 75, 7503190030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zippenfening, H.A.; Răican, D. Broșură—Recomandări Pentru cei Apropiați Persoanelor cu Boala Parkinson; Asociația de Parkinson: București, Romania, 2015; pp. 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Durner, J.; Fickert, G.; Kröner, W.; Stadler, B. Training fȕr das Leben im Alltag—Physio-und ergotherapeutische Anleitng zum Eigentraining fȕr Parkinson-Patienten; Fachklinik: Ichenhausen, Germany, 1998; pp. 40–61. [Google Scholar]

- Varadi, C. Clinical Features of Parkinson’s Disease: The Evolution of Critical Symptoms. Biology 2020, 9, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iordan, D.A.; Munteanu, C.; Constantin, G.B.; Onu, I.; Nechifor, A. Age-Related Sport-Specific Dysfunctions of the Shoulder and Pelvic Girdle in Athletes Table Tennis Players. Observational Study. Balneo PRM Res. J. 2021, 12, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etoom, M.; Alwardat, M.; Aburub, A.S.; Lena, F.; Fabbrizo, R.; Modugno, N.; Centonze, D. Therapeutic interventions for Pisa syndrome in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. A Scoping Systematic Review. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2020, 198, 106242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ninomiya, S.; Morita, A.; Teramoto, H.; Akimoto, T.; Shiota, H.; Kamei, S. Relationship between Postural Deformities and Frontal Function in Parkinson’s Disease. Park. Dis. 2015, 2015, 462143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Warburton, D.E.; Nicol, C.W.; Bredin, S.S. Health benefits of physical activity: The evidence. CMAJ 2006, 174, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Liria, R.; Vega-Tirado, S.; Valverde-Martínez, M.Á.; Calvache-Mateo, A.; Martínez-Martínez, A.M.; Rocamora-Pérez, P. Efficacy of Specific Trunk Exercises in the Balance Dysfunction of Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sensors 2023, 23, 1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandolfi, M.; Tinazzi, M.; Magrinelli, F.; Busselli, G.; Dimitrova, E.; Polo, N.; Manganotti, P.; Fasano, A.; Smania, N.; Geroin, C. Four-week trunk-specific exercise program decreases forward trunk flexion in Parkinson’s disease: A single-blinded, randomized controlled trial. Park. Relat. Disord. 2019, 64, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yitayeh, A.; Teshome, A. The effectiveness of physiotherapy treatment on balance dysfunction and postural instability in persons with Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2016, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opara, J.; Małecki, A.; Małecka, E.; Socha, T. Motor assessment in Parkinson’ s disease. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2017, 24, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MDS-UPDRS. The MDS-Sponsored Revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale. Official MDS Romanian Translation. 2018 International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society. Available online: https://www.movementdisorders.org/MDS-Files1/PDFs/MDS-UPDRS-Rating-Scales/MDS_UPDRS_Romanian_OfficialTranslation_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Cocks, K.; Torgerson, D.J. Sample size calculations for pilot randomized trials: A confidence interval approach. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2013, 66, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borrero, L.; Miller, S.A.; Hoffman, E. The meaning of regular participation in vigorous-intensity exercise among men with Parkinson’s disease. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 2385–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Kolk, N.M.; de Vries, N.M.; Kessels, R.P.C.; Joosten, H.; Zwinderman, A.H.; Post, B.; Bloem, B.R. Effectiveness of home-based and remotely supervised aerobic exercise in Parkinson’s disease: A double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 998–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schenkman, M.; Moore, C.G.; Kohrt, W.M.; Hall, D.A.; Delitto, A.; Comella, C.L.; Josbeno, D.A.; Christiansen, C.L.; Berman, B.D.; Kluger, B.M.; et al. Effect of high-intensity treadmill exercise on motor symptoms in patients with de novo Parkinson disease: A phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2018, 75, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schootemeijer, S.; van der Kolk, N.M.; Ellis, T.; Mirelman, A.; Nieuwboer, A.; Nieuwhof, F.; Schwarzschild, M.A.; de Vries, N.M.; Bloem, B.R. Barriers and Motivators to Engage in Exercise for Persons with Parkinson’s Disease. J. Park. Dis. 2020, 10, 1293–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, Z.; Russel, J. Delay the Disease—Exercises and Parkinson’s Disease, 2nd ed.; OhioHealth: Columbus, OH, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Falup-Pecurariu, C. Boala Parkinson și alte Tulburări de Mișcare- de la Diagnostic la Tratament. Habilitation Thesis, Universitatea Transylvania University of Brasov, Brasov, Romania, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sangarapillai, K.; Norman, B.M.; Almeida, Q.J. An equation to calculate UPDRS motor severity for online rural assessments of Parkinson’s. Park. Relat. Disord. 2022, 94, 96–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, C.; Arora, S.; Lawton, M.; Barber, T.; Quinnell, T.; Dennis, G.J.; Ben-Shlomo, Y.; Hu, M.T. A composite clinical motor score as a comprehensive and sensitive outcome measure for Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2022, 93, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mak, M.K.; Wong-Yu, I.S.; Shen, X.; Chung, C.L. Long-term effects of exercise and physical therapy in people with Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2017, 13, 689–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).