An Evaluation of the Effects of a Virtual Museum on Users’ Attitudes towards Cultural Heritage

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

- A change in attitudes depends on the person that receives the information.

- In particular, how he/she cognitively responds towards it in positive–negative, good–bad, or favorable–unfavorable terms.

- When people take time to think, the direction of what is thought leads to consistent attitudes.

- When attitudes are formed from mechanisms of much thought, they are related to behavior.

2.1. The Relationship between Digital Products and Attitudes

2.2. Virtual Museum

2.3. Interactive Website

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Procedure and Design

3.3. Instruments

3.3.1. Independent Variables and Measurements

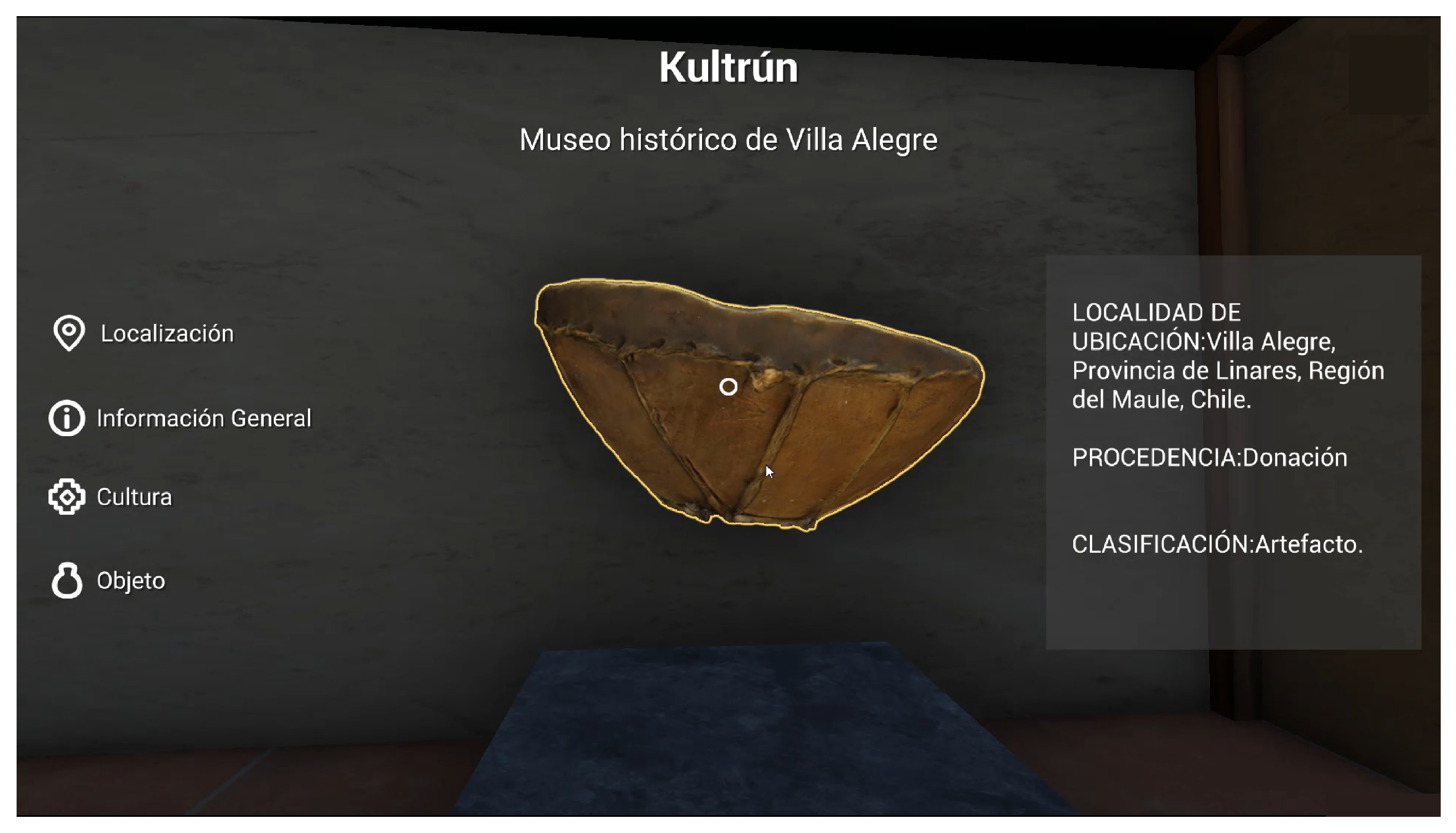

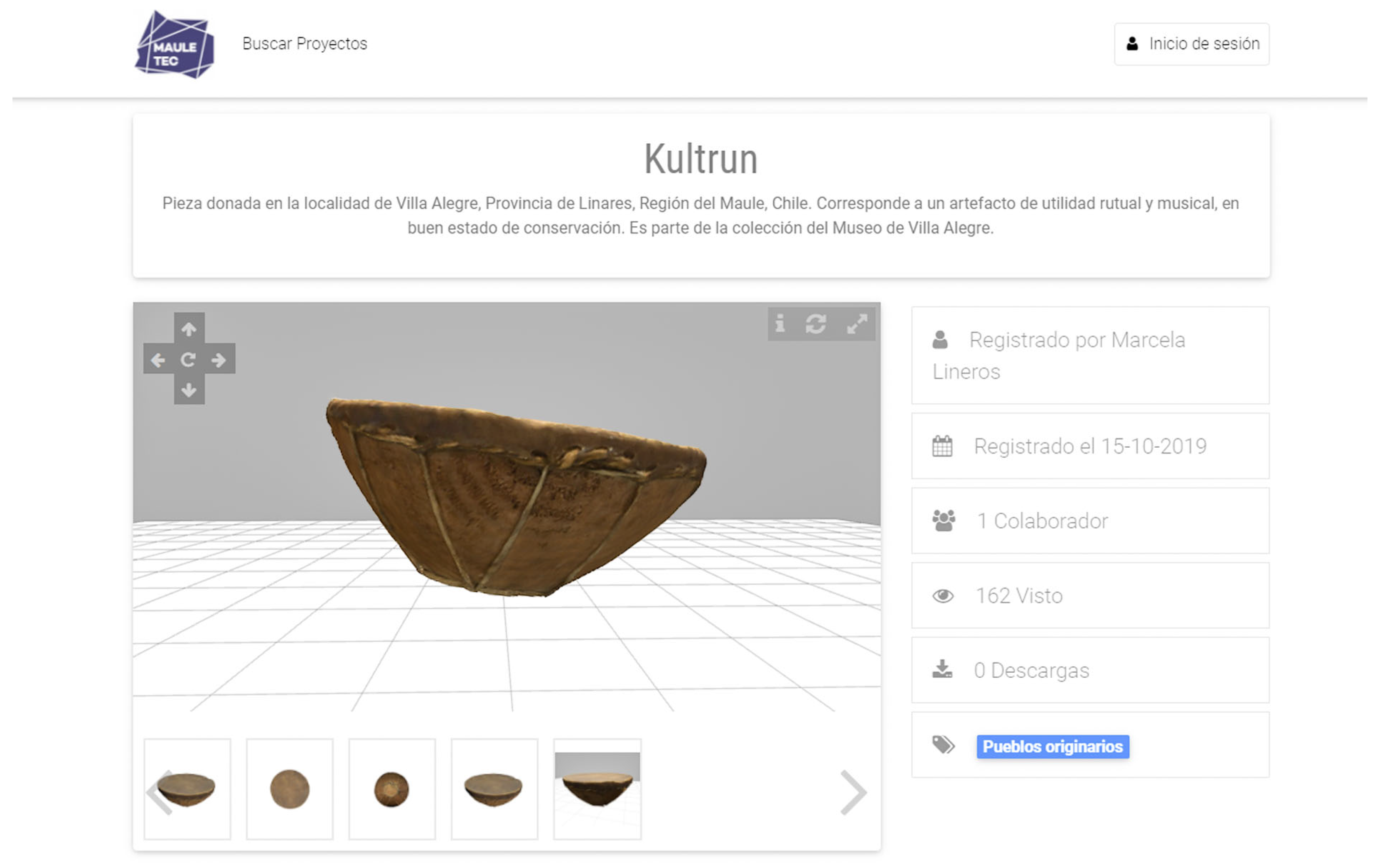

- Type of multimedia experience: As a means of controlling the type of multimedia experience that participants took part in, half of them were provided with a Windows Store download link for a 3D simulator containing a variety of virtual copies of real life cultural heritage objects from the Maule region [7]. The other half of the participants received a link to an interactive website hosted on the University’s website. This web page contained the same objects as the simulator but, in this case, presented through photographs.

- Thought favorability: Participants received a web questionnaire with ten open-ended question blocks for them to list their thoughts about the multimedia experience. They were asked to write one thought for each block (examples on the use of the thought-listing technique can be found on [39,40,41,42] Two independent judges who did not know about the conditions and experimental hypotheses subsequently codified these thoughts as positive, negative, or neutral toward the experience and resolved their disagreements through discussion. Some examples of positive and negative thoughts are, respectively: “I think it’s innovative and fun” and “The place causes me anxiety”. Using only the thoughts that related to the experience, an index of favorability of thoughts was created, subtracting the number of negative thoughts from the number of positive ones and dividing by the sum of both quantities.

- Presence index: We used the SUS scale of presence [33,43,44]. This instrument was answered in a seven-point Likert format (e.g., “Please rate your sense of being present in the multimedia experience, on a scale of 1 to 7, where 1 represents your normal experience of being in a place”; “To what extent were the times when the multimedia experience was the reality for you?”). A reliability analysis including the six items was performed, showing an appropriate but low reliability (a = 0.67). This improved when discarding item 6 (“During the experience, did you often think that you actually were in the multimedia experience?”). Due to this change, a sole index was created using only the first five items (a = 0.76).

3.3.2. Dependent Variables

- Attitudes: Participants answered a series of semantic differential items (e.g., “I think the multimedia experience is pleasant/unpleasant”) to assess their attitudes toward the multimedia experience. Four indexes of attitudes toward different elements measured by the questionnaire were generated. These were index of attitudes toward the multimedia experience, index of attitudes toward cultural heritage, index of attitudes toward visiting a virtual museum, and index of attitudes toward visiting a museum in person. Due to the high internal consistency within and between the different items (a = 0.84 for the index of attitudes toward cultural heritage being the lowest value), we decided to group items by indexes of attitudes. Each index was composed by the average of six semantic differential items (“pleasant–unpleasant”, “good–bad”, “necessary–unnecessary”, “negative–positive”, “I like it–I do not like it”, and “favorable–unfavorable”), rated on a scale of 1 to 7. Items were inverted to make it so that more positive values indicated more favorable attitudes. This procedure has been adapted from previous research [45]. Finally, due to the high consistency of the four indexes of attitudes toward the multimedia experience, we derived them from them an overall index of attitudes toward the heritage (a = 0.79).

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analysis

4.2. Attitudes

4.2.1. Overall Index of Attitudes

4.2.2. Attitudes towards the Multimedia Experience

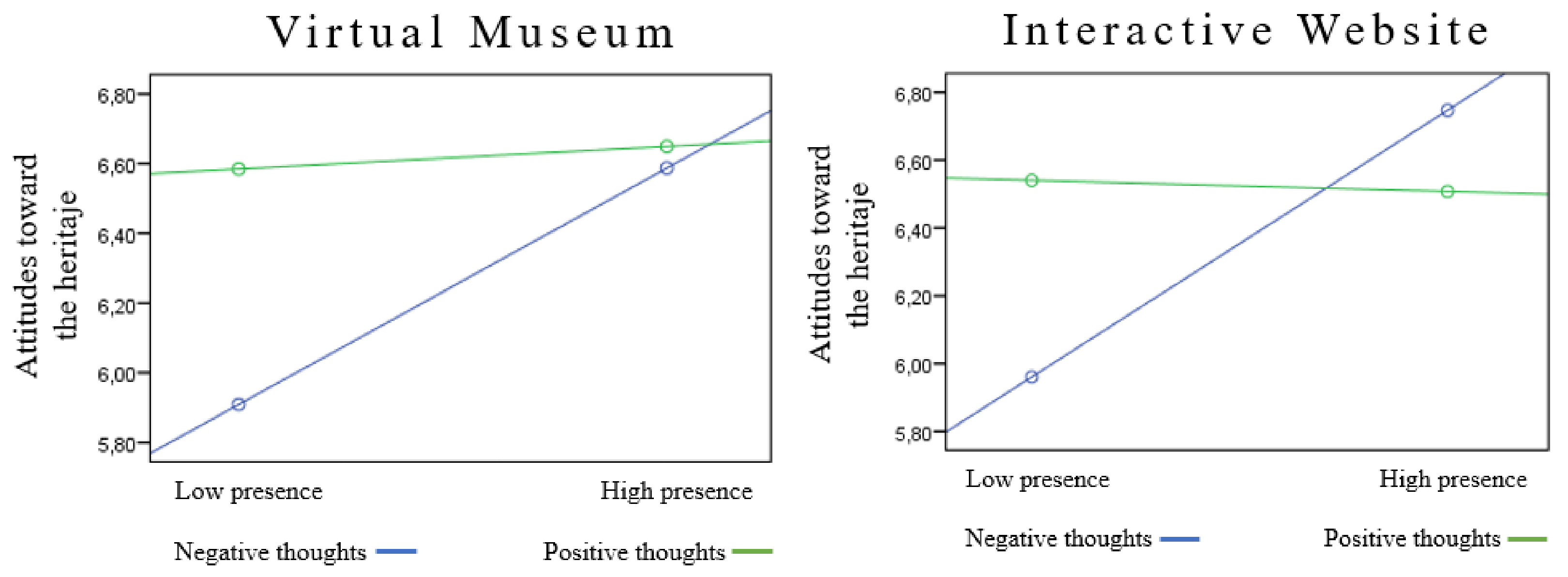

4.2.3. Attitudes towards Heritage

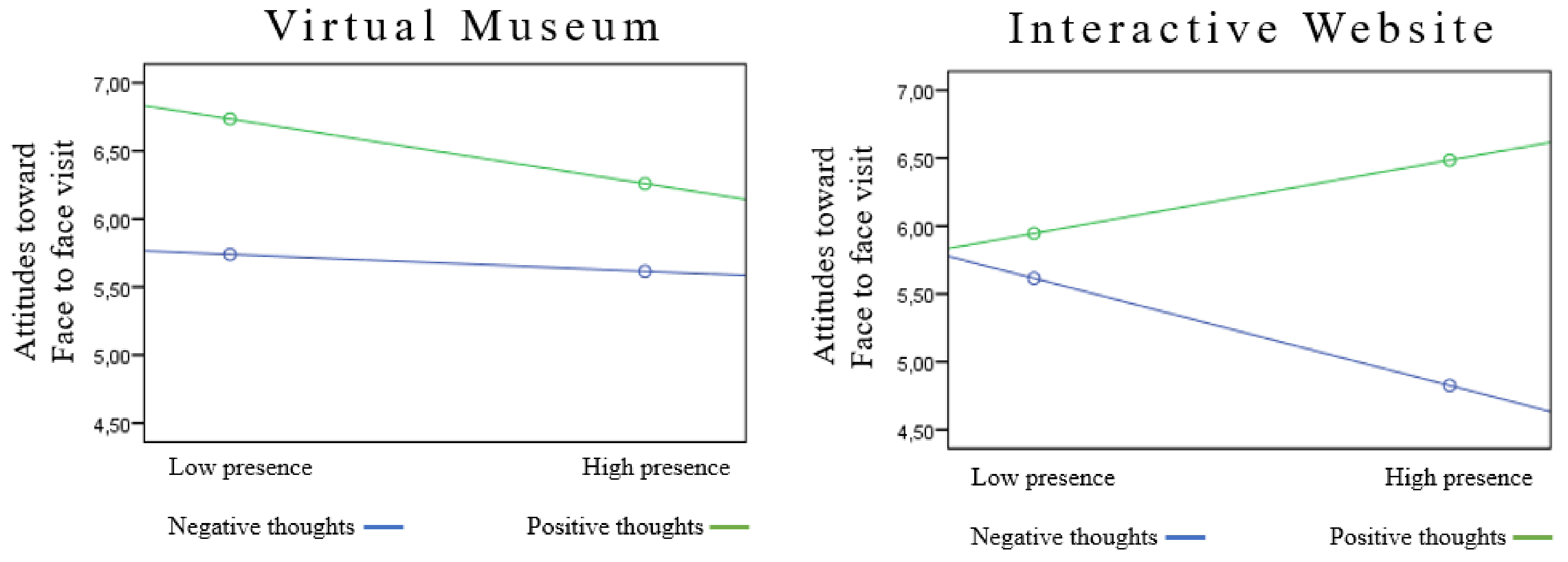

4.2.4. Attitudes towards Face-to-Face Visits

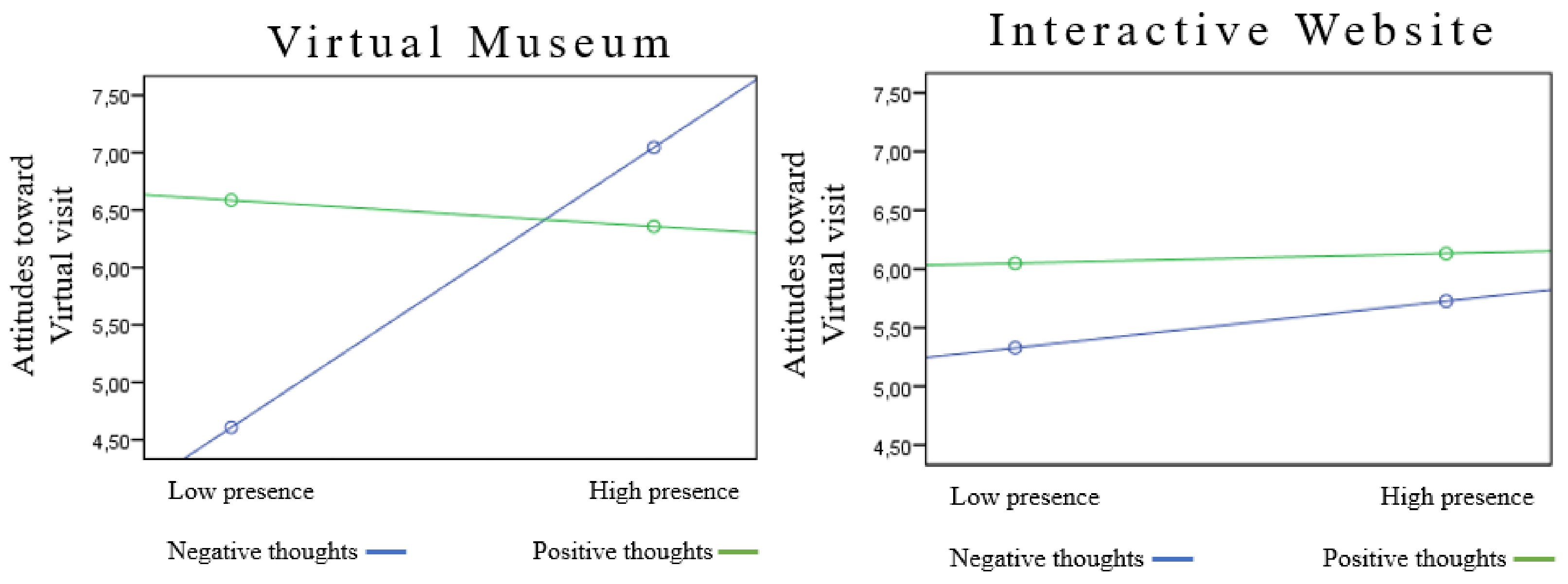

4.2.5. Attitudes towards a Virtual Visit

5. Discussion

Limitations and Future Work

- The time that participants dedicated to each condition of the test (virtual museum and interactive website): as the simulator and the website were hosted on different servers, we were not able to measure time of observation, which is associated with more capacity to analyze the information as people invest more time [21]. It might be the case that a certain multimedia experience is related to the investment of more time, affecting the results.

- Other demographic variables: we did not include other demographic variables besides gender and age because we do not have any hypothesis regarding alternative variables to understand potential differences between the types of systems and attitudes. Since participants were randomly assigned, the potential bias from those demographics is constant across conditions. Nevertheless, we analyzed if there were any differences in the percentage of men and women or age between conditions. A chi-square analysis showed no significant differences between gender ((2) = 4.18; p = 0.12) and age (t(96) = 0.95; p = 0.34), suggesting that potential differences in sample distribution are not responsible for our results.

- Controlling the time investment and including a new and more immersive multimedia experience: this could be applied using the VR version of the virtual museum with Oculus devices (i.e., HMD). More importantly, the results of this study allow for a discussion about the potential reasons that underlie the shown effects. For example, if the multimedia experience does not lead to more presence, what is the role of those types of experiences? Some research showed that the effect of different devices or experiences on attitudes are based on immersion (an objective measure of a virtual device) rather than presence [32]. Then, how can presence be enhanced? Research on transportation [47] showed that a feeling of “being there” is enhanced when a story precedes the experience, inviting the user to imagine the place. In our case, both experiences have the same story, which might be the reason for the absence of differences.

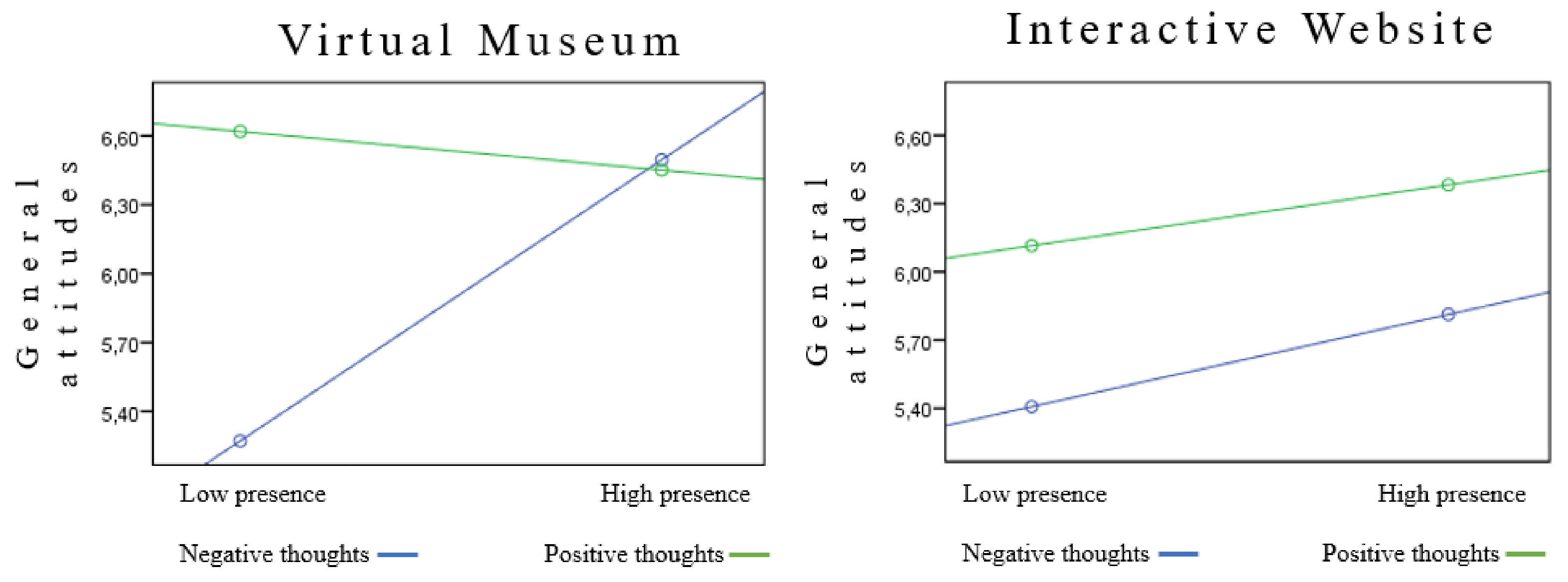

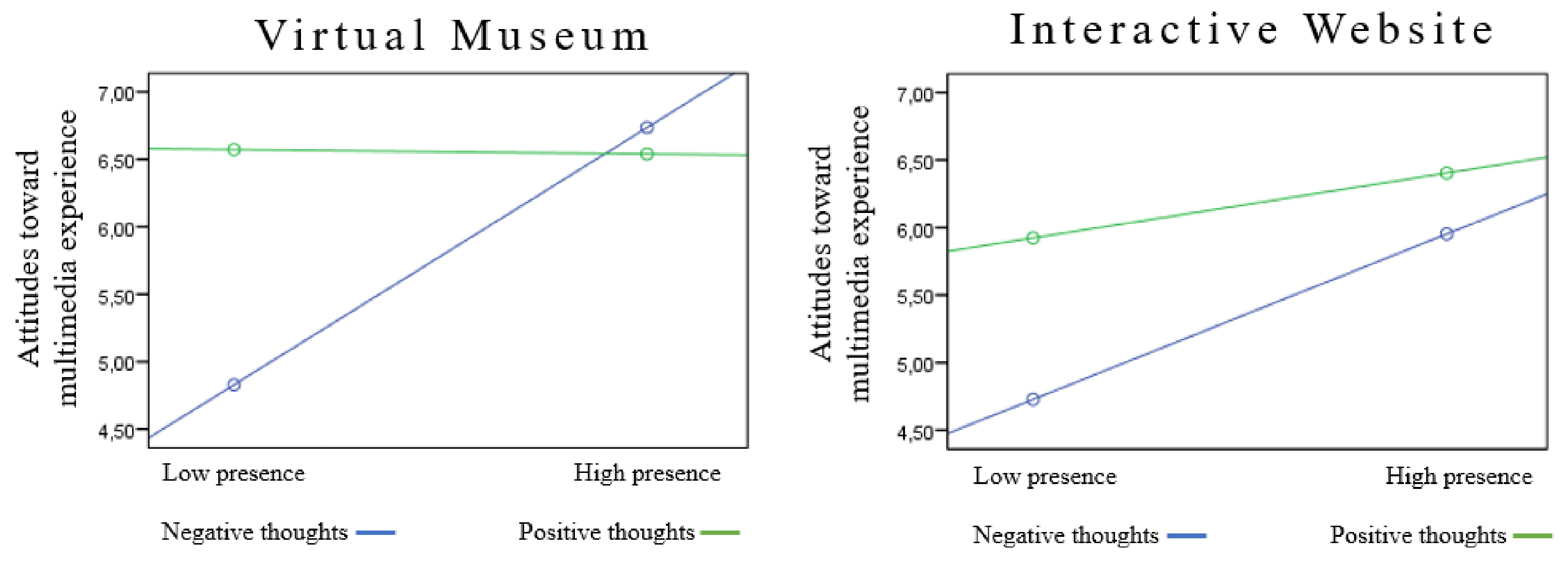

- Exploring different objects and simulated situations to replicate the pattern of results of the present study: this includes several factors such as integrating presence and thought favorability, along with other variables such as changes in the level of detail (LoD) of the software. Traditionally, an increase in LoD tends to enhance attitudes by itself. However, based on our results, LoD might lead to positive or negative attitudes depending on the variable that it interacts with. Moreover, it might be the case that LoD has no influence at all when the story behind the software is interesting and engaging [47]. Thus, a software with a very low LoD might lead to positive attitudes if it is based on a good story (i.e., lead to favorable thoughts), in a similar vein that reading a good book (a very low LoD) leads to satisfaction when it is finished. This pattern of predictions is observed in Figure 4, right panel (pag. 8). However, depending on the attitudinal object, the previous pattern might change on interacting with presence and thought favorability (as in attitudes toward face-to-face visits). Finally, it could be interesting to analyze changes in other attitudinal objects related to heritage when individuals explore a simulated or a web-based museum. For example, attitudes toward local entrepreneurship, hand-crafting, or rural tourism could change if they are psychologically linked to the primary object, leading to an indirect change in attitudes (e.g., [48]).

- Continuing research on attitude change: Figure 4 shows that, regarding general attitudes, positive and negative thoughts lead to similar results on attitudes as presence increases but to main effects when there is low presence. Following the elaboration likelihood model of persuasion (ELM, [21]), it could be that high presence in a virtual experience, since it is a positive feeling, might reduce the motivation to think and the effect of thought direction. It also might be the case that presence affects the validity of thoughts [28], reducing their impact on attitudes, especially with the negative ones (“I thought that museums are bad, but after the experience, I seriously doubt that”). In any case, our results show that the analysis of the effect of a virtual museum on attitudes toward cultural heritage is not derived only by simple effects, but especially for interactions that can guide some theoretical explanations for the observed consequences. In the future, the study of cultural heritage can benefit from interventions observing thoughts and feelings of presence, providing new insights for understanding attitude change in the ICT context.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| HDM | Head-Mounted Display |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technologies |

References

- Cuetos, M.P.G. El Patrimonio Cultural. Conceptos Básicos; Universidad de Zaragoza: Zaragoza, Spain, 2012; Volume 207. [Google Scholar]

- The Criteria for Selection-UNESCO. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/criteria/ (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Almeida, F.; Duarte Santos, J.; Augusto Monteiro, J. The Challenges and Opportunities in the Digitalization of Companies in a Post-COVID-19 World. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2020, 48, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augmented (AR), Virtual Reality (VR), and Mixed Reality (MR) Market Size Worldwide from 2021 to 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/591181/global-augmented-virtual-reality-market-size/ (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Russo, M. AR in the Architecture Domain: State of the Art. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, M.K.; Champion, E.; McMeekin, D.A.; Rahaman, H. The Influence of Collaborative and Multi-Modal Mixed Reality: Cultural Learning in Virtual Heritage. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2021, 5, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besoain, F.; Jego, L.; Gallardo, I. Developing a Virtual Museum: Experience from the Design and Creation Process. Information 2021, 12, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jego, L.; Gallardo, I.; Besoain, F. Developing a Virtual Reality Experience with Game Elements for Tourism: Kayak Simulator. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE CHILEAN Conference on Electrical, Electronics Engineering, Information and Communication Technologies (CHILECON), Valparaiso, Chile, 13–27 November 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, H. Photogrammetry: What, How, and Where. In Virtual Heritage: A Guide; Champion, E.M., Ed.; Ubiquity Press: London, UK, 2021; pp. 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegó, L.; Aliaga, C.; Besoain, F. A framework for digitizing historical pieces for the development of interactive software. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE CHILEAN Conference on Electrical, Electronics Engineering, Information and Communication Technologies (CHILECON), Valparaiso, Chile, 13–27 November 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Museo Nacional de Historia Natural Digitaliza Colecciones en 3D. Available online: https://www.patrimoniocultural.gob.cl/noticias/museo-nacional-de-historia-natural-digitaliza-colecciones-en-3d (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Sketchfab|MNHN Chile. Available online: https://sketchfab.com/MNHNcl (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Champion, E. (Ed.) Virtual Heritage; Ubiquity Press: London, UK, 2021; p. 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loaiza Carvajal, D.A.; Morita, M.M.; Bilmes, G.M. Virtual museums. Captured reality and 3D modeling. J. Cult. Herit. 2020, 45, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzima, S.; Styliaras, G.; Bassounas, A. Revealing Hidden Local Cultural Heritage through a Serious Escape Game in Outdoor Settings. Information 2021, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweibenz, W. The virtual museum: An overview of its origins, concepts, and terminology. Mus. Rev. 2019, 4, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Oculus Go: Standalone VR Headset|Oculus. Available online: http://web.archive.org/web/20190607051256/https://www.oculus.com/go/ (accessed on 7 July 2019).

- Oculus Quest 2|Oculus. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20210217103845/https://www.oculus.com/quest-2/ (accessed on 7 July 2019).

- Slater, M. A note on presence terminology. Presence Connect. 2003, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, D.A.; McMahan, R.P. Virtual reality: How much immersion is enough? Computer 2007, 40, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. In Communication and Persuasion; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1986; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Killeya, L.A.; Johnson, B.T. Experimental induction of biased systematic processing: The directed-thought technique. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 24, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fabrigar, L.R.; MacDonald, T.K.; Wegener, D.T. The Structure of Attitudes. In The Handbook of Attitudes; Albarracín, D., Johnson, B.T., Zanna, M.P., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Albarracín, D.; Johnson, B.T.; Zanna, M.P. The Handbook of Attitudes; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Briñol, P.; Petty, R.E. Persuasion: Insights from the self-validation hypothesis. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 41, 69–118. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly, A.H.; Chaiken, S. The Psychology of Attitudes; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College: San Diego, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly, A.H.; Chaiken, S. The advantages of an inclusive definition of attitude. Soc. Cogn. 2007, 25, 582–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinol, P.; Petty, R.E. Self-Validation Theory: An Integrative Framework for Understanding When Thoughts Become Consequential. Psychol. Rev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, A.G. Cognitive learning, cognitive response to persuasion, and attitude change. In Psychological Foundations of Attitudes; Academic Press Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1968; pp. 147–170. [Google Scholar]

- Briñol, P.; Petty, R.E.; Guyer, J.J. A historical view on attitudes and persuasion. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology; Oxford University Press (OUP): Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tussyadiah, I.P.; Wang, D.; Jia, C.H. Virtual reality and attitudes toward tourism destinations. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2017; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 229–239. [Google Scholar]

- Mütterlein, J.; Hess, T. Immersion, presence, interactivity: Towards a joint understanding of factors influencing virtual reality acceptance and use. In Proceedings of the 23rd Americas Conference on Information Systems (AMCIS), Boston, MA, USA, 10–12 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Witmer, B.G.; Jerome, C.J.; Singer, M.J. The factor structure of the presence questionnaire. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 2005, 14, 298–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steuer, J. Defining virtual reality: Dimensions determining telepresence. J. Commun. 1992, 42, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P.; Wang, D.; Jung, T.H.; tom Dieck, M.C. Virtual reality, presence, and attitude change: Empirical evidence from tourism. Tour. Manag. 2018, 66, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Museo Virtual del Maule|Laboratorio Mauletec Chile. Available online: https://www.microsoft.com/es-cl/p/museo-virtual-del-maule/9pk32gvfkr2h (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Briñol, P.; Petty, R.E.; Tormala, Z.L. Self-validation of cognitive responses to advertisements. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 30, 559–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. Attitude and attitude change. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1981, 32, 357–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briñol, P.; Horcajo, J.; Becerra, A.; Falces, C.; Sierra, B. Cambio de actitudes implícitas. Psicothema 2002, 14, 771–775. [Google Scholar]

- Briñol, P.; Horcajo, J.; Becerra, A.; Falces, C.; Sierra, B. Equilibrio cognitivo implícito. Psicothema 2003, 15, 375–380. [Google Scholar]

- Falces, C.; Briñol, P.; Sierra, B.; Becerra, A.; Alier, E. Validación de la escala de necesidad de cognición y su aplicación al estudio del cambio de actitudes. Psicothema 2001, 13, 622–628. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, E. Introducing the Thought-Listing Technique to Measure Affective Factors Influencing Attitudes toward Science. Univ. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 8, 2245–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, M.; Usoh, M.; Steed, A. Depth of presence in virtual environments. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 1994, 3, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witmer, B.G.; Singer, M.J. Measuring presence in virtual environments: A presence questionnaire. Presence 1998, 7, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briñol, P.; Becerra, A.; Gallardo, I.; Horcajo, J.; Valle, C. Validación del pensamiento y persuasión. Psicothema 2004, 16, 606–610. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 2018, 85, 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.C.; Brock, T.C. The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horcajo, J.; Briñol, P.; Petty, R.E. Consumer persuasion: Indirect change and implicit balance. Psychol. Mark. 2010, 27, 938–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Besoain, F.; González-Ortega, J.; Gallardo, I. An Evaluation of the Effects of a Virtual Museum on Users’ Attitudes towards Cultural Heritage. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1341. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031341

Besoain F, González-Ortega J, Gallardo I. An Evaluation of the Effects of a Virtual Museum on Users’ Attitudes towards Cultural Heritage. Applied Sciences. 2022; 12(3):1341. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031341

Chicago/Turabian StyleBesoain, Felipe, Jorge González-Ortega, and Ismael Gallardo. 2022. "An Evaluation of the Effects of a Virtual Museum on Users’ Attitudes towards Cultural Heritage" Applied Sciences 12, no. 3: 1341. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031341

APA StyleBesoain, F., González-Ortega, J., & Gallardo, I. (2022). An Evaluation of the Effects of a Virtual Museum on Users’ Attitudes towards Cultural Heritage. Applied Sciences, 12(3), 1341. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031341