Abstract

This paper proposes an emotion recognition method for tweets containing emoticons using their emoticon image and language features. Some of the existing methods register emoticons and their facial expression categories in a dictionary and use them, while other methods recognize emoticon facial expressions based on the various elements of the emoticons. However, highly accurate emotion recognition cannot be performed unless the recognition is based on a combination of the features of sentences and emoticons. Therefore, we propose a model that recognizes emotions by extracting the shape features of emoticons from their image data and applying the feature vector input that combines the image features with features extracted from the text of the tweets. Based on evaluation experiments, the proposed method is confirmed to achieve high accuracy and shown to be more effective than methods that use text features only.

1. Introduction

Emoticons are nonverbal expressions that are composed by combining characters. They are typically embedded in text and are widely used in multibyte character languages that have many character types, such as Japanese. By adding emoticons to text, it is possible to flexibly express emotions and intentions that are otherwise difficult to convey using only character information. Presently, in addition to emoticons, various other forms of nonverbal expressions, such as emojis and stamps, are used in text-based communications.

However, because there are very few other expressions that can be used with the same ease and versatility as emoticons, it is expected that they will be used extensively in the future. However, emoticons have a higher degree of polysemy than emojis, and their meanings often change when combined with sentences. Hence, it is difficult to ascertain emotions and intentions using only emoticons. In this study, to ascertain the emotions expressed by entire sentences from tweets including emoticons, we focus on the shape features of the emoticons and propose a method to combine these extracted features with textual features.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses previous studies related to emoticons and explains how they differ from this study. Section 3 describes the proposed method for estimating emotions from text with emoticons. Section 4 outlines the experiments conducted to evaluate the validity of the proposed method. Section 5 analyzes the experimental results obtained. Section 6 presents concluding remarks.

2. Related Work

This section introduces previous studies on emotion estimation from emoticons, emotion estimation from sentences containing emoticons, and emotion estimation from sentences containing pictograms, and describes how they differ from the present study.

2.1. Emotion Estimation from Emoticons

To estimate emotions from emoticons, Fujisawa et al. [1] focused on the appearance of the emoticons as cues. Emoticons are generally composed of character strings. Therefore, when considering emoticons as research objects, we often focus on each character individually. Fujisawa et al. proposed a method to obtain shape information from the entire emoticon by converting its text data to image data and classifying the corresponding emotions using shape information as features. This method allows the capturing of the entire image of the emoticon as a feature, rather than focusing on the individual characters. In addition, this method was shown to be effective for unknown emoticons that were not included in the training data.

Yu et al. [2] proposed a new system, called AZEmo, which extracts emoticons from Chinese social media and other sources and classifies them into seven emotional categories. The system is based on a kinesics model that divides emoticons into semantic regions (eyes, mouth, etc.). This model has been modified to adapt to the Chinese context.

Takishita et al. [3] focused on emoticons and onomatopoeia in documents to extract the emotions associated with the contents of the entire documents. In their work, Takishita et al. investigated the effects of onomatopoeia on the emotions expressed using emoticons; accordingly, they estimated the emotions implied by emoticons. In the case of a combination of an emoticon and onomatopoeia, each of which express different emotions, Takishita et al. considered both the possible precedence of only one of the emotions over the others as well as the expression of a completely new emotion.

Ptaszynski et al. [4] identified the correspondences between emoticons and their corresponding linguistic expressions, such as onomatopoeia, and estimated the degree of ambiguity in the general meaning of emoticons. They surveyed users regarding the meanings of emoticons, and applied the results of the survey to quantify the understandability (meaning ambiguity) of emoticons. Based on their results, they applied emotions that can be expressed in everyday vocabulary to identify the ambiguity of emoticons’ meanings.

Matsumoto et al. [5] proposed a method for emotion estimation that learns the character features of emoticons with a convolutional neural network. In their method, the characters of emoticons are converted into character variance representation by word2vec, and their weights are used as initial parameters that are input to a one-dimensional convolutional neural network. They targeted the five emotions Joy, Surprise, Anger, Sorrow, and Neutral. However, because it is more difficult to capture the meaning of character variants than word variants and because it depends on the quality and quantity of the unsupervised text data, it is necessary to capture the prerequisite knowledge of how each character is used in emoticons.

Several studies have been conducted with the objective of estimating the emotions of individual emoticons [6]. On the one hand, emoticons are used to express a variety of emotions. On the other hand, when emoticons appear as part of a sentence, it is very difficult to estimate the emotion of the sentence and the emoticon.

2.2. Emotion Estimation from Sentences Containing Emoticons

Jiang et al. [7] investigated the effects of emoticons on the emotions implied by tweets on Twitter; they compared tweets with and without emoticons and formulated relationships between them and the expected emotions. Furthermore, they quantitatively assessed the emotions of not only sentences but also each of the emoticons individually. They concluded that using the emotions implied by the emoticons is effective for improving the accuracy of emotion estimation from short sentences such as tweets.

Wegrzyn-Wolska et al. [8] investigated the effects of emoticons on the entire sentence by estimating emotions from tweets under various scenarios, such as when emoticons were removed from the sentences and when binary labels (positive/negative) were assigned in the absence of emotion labels. However, the emoticons used by Wegrzyn-Wolska et al. were of the western style, which are slightly different from the Japanese-style emoticons considered in this present study. Table 1 shows examples of each type of emoticon. In this manner, according to the various types of emoticons used in different countries, it is important to use different analysis methods that are appropriate for each type of emoticon.

Table 1.

Examples of emoticons (Western vs. Japanese).

In addition to the studies cited above, many others have been conducted with the objective of estimating emotions in sentences containing emoticons [9,10]. In existing research, dictionary-based matching has been the main method for estimating the emotions of emoticons. First, the emotions expressed by the emoticons are estimated based on dictionary data, and then the emotions of the entire sentence are estimated based on the estimated emotions of the emoticons. However, we believe that there is a shortcoming in the creation of the dictionary data. Emoticons are expressions created by combining symbols, and the variety of emoticons is enormous. In addition, depending on the language in which the emoticons are used, the applicable characters and symbols may differ even if they look the same (e.g., ellipsis: “-“; ruled: “–––”; dash: “-”, etc.). In the case of character-based emoticons, if the parts of the emoticon are different, we need to register each part as a different emoticon. Consequently, in our approach, in addition to character-based recognition, we use a method that treats emoticons as images. In this way, we can estimate the emotions of unknown emoticons by referring to the existing dictionary data if they are composed of visually similar parts. Table 2 shows the differences and advantages of our method in relation to existing emotion estimation methods that include emoticons.

Table 2.

Comparison of the proposed method with existing methods.

2.3. Emotion Estimation from Sentences Containing Emojis

Similar to emoticons, emojis are nonverbal expressions that are also used inline in text. Emojis are generally created in image format or using Unicode characters and used to express emotions and responses.

Ahanin et al. [11] used fuzzy clustering to group emojis into one or more emotion classes; then, they developed pretrained embeddings for these emojis. By comparing the embeddings for emojis with existing word embeddings excluding emojis, Ahanin et al. determined the effectiveness of emojis for tasks involving sentiment and emotion analyses. More studies are available on the subject of emojis than on emoticons. The main difference between emojis and emoticons is that they are either image or text data. In addition, emojis cannot be used without predesigned system items supported by a system, and there are only 20 to 30 types of facial expressions. Emoticons, however, are generated by combining characters and symbols such that we can freely create expressions depending on a situation. Thus, emoticons are available in a wider variety and allow more flexibility.

Cherbonnier et al. [12] compared the recognition of human emotions based on their new emoji with other forms of expression (facial expressions and Facebook and iOS emojis). Their new emojis are designed to convey six basic emotions (Anger, Disgust, Happiness, Surprise, Fear, Sadness). Their experimental results revealed that the new emojis are more likely than other expressive techniques to recognize disgust and sadness. Although their research focuses solely on the recognition of emotions in pictograms, and does not include a method for automatically recognizing emotions from pictogram information, it shows that depending on the type of pictogram, the sender and receiver may not be able to accurately recognize emotions.

Fujino et al. [13] constructed a neural network-based emotion estimation model for each gender of the speaker by constructing a pseudo-emotion-labeled speech corpus using tweets containing emoji and automatically expanding the corpus. Their work is based on Emoji2vec [14], which vectors pictograms and assigns labels to four types of emotions—Joy, Anger, Sorrow, and Surprise—based on their similarity. Although their proposed method can compensate for the lack of a corpus, it is difficult to improve the accuracy because it contains noise.

In addition to Japanese texts, research has been conducted on texts containing pictograms in Chinese, Turkish, Arabic, and other languages. There are many other studies that use emojis as a cue for emotion estimation, and many have also evaluated the effectiveness of emojis experimentally [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. The number of studies on emoticons is small compared to those on pictograms. However, emoticons and pictograms are similarly used for emotional expression. Therefore, we believe that both emoticons and pictograms can provide effective clues for sentiment analysis.

3. Proposed Method

In this study, we primarily focus on the shape features of emoticons. Fujisawa et al. [1] proposed a method to estimate emotions expressed by emoticons by converting them into images and extracting some shape features. Their method achieved highly accurate emotion classification by dividing the emoticons into character units and synthesizing features from each character unit. However, the positions of the characters are important for emoticons. In many cases, a certain shape is formed by a sequence of letters. Therefore, to improve the estimation accuracy, it is necessary to use methods such as the edit distance by considering the character arrangements and the relatively high calculation costs of machine-learning methods such as recurrent neural networks.

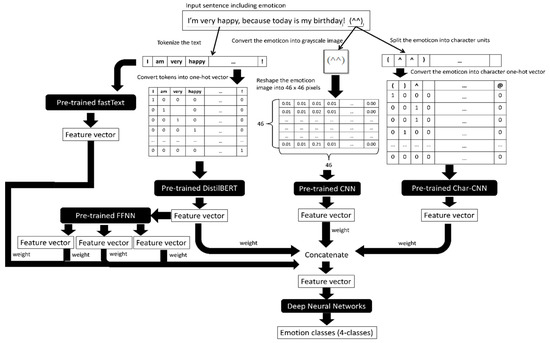

Methods that use character n-grams as features and character-level convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have also been proposed. CNNs are popular for image recognition tasks, and AlexNet [23] and ResNet [24] are typical models. In terms of using CNN for text data, Character-Level CNN (CLCNN) has been proposed in the field of natural language processing. CLCNN is a one-dimensional CNN that is used in text classification or detecting words [25,26]. In our proposed method, we extract emoticon features from emoticon images using CNNs. This allows us to consider the positional relationships between the characters to handle the shape features of emoticons well. Figure 1 shows the flow of our proposed method.

Figure 1.

Overview of the proposed method.

3.1. Extraction of Emoticon Features (ev) Based on Deep Learning

Our proposed method extracts the image features of emoticons and converts them into 64-dimensional feature vectors using a prelearned model. The pretrained model is an emotion classifier trained using a deep CNN based on an emoticon dictionary. In addition, to compensate for the shortage of emoticon data during pretraining, image data were augmented using multiple character fonts as one of the data-augmentation methods. Most of the existing pretrained networks are applicable to color images; however, monochrome images are generally out of scope of such models. Because emoticons do not have any color information, we designed and trained a new model from scratch.

Figure 2 shows the network configuration used in this study for pretraining of the CNN. The emotion labels are predicted using the convolution and max-pooling layers with SoftMax as the activation function in the output layer. In this model, the emotions are recognized solely via the image features of the emoticons, such that learning progression allows the overfitting caused by the emotions that are associated with the emoticon units only. Thus, robustness to unknown emoticons is lost, and so a dropout function is placed after the fully connected layer.

Figure 2.

Deep convolutional neural networks employed for emotion estimation from emoticons.

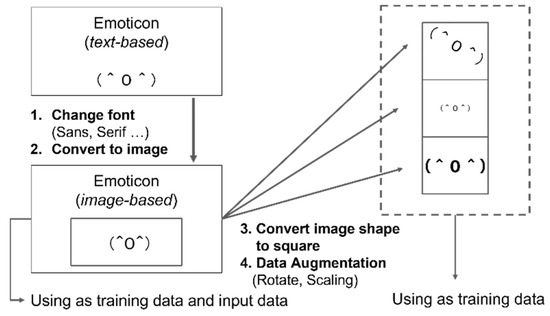

In addition, because emoticons are created by connecting multiple characters horizontally, their widths are greater than their heights. If the aspect ratio of the emoticon image is converted as is, the characters are crushed, and the original shape information will be lost. As this would affect the feature learning process, we considered appropriate margins at the tops and bottoms of the images and converted them into square-shaped images without changing the aspect ratios of the emoticons themselves. This enables easier handling during convolution in the CNN. Specifically, the input emoticon image is grayscale, with vertical and horizontal dimensions of 46 pixels each.

Figure 3 shows the process of converting the emoticon to image data. In the proposed method, we treat emoticons as image data as well. When converting text to images, the same character can look different if the character font is different. Therefore, in this study, we prepared emoticons in text format in various fonts and converted them to image data.

Figure 3.

The emoticons to images conversion process.

The CNN then learns from the abovementioned data-augmented training images, and the image features of the emoticons are input to the trained CNN to obtain the output of the hidden layer (fully connected layer). This output 64-dimensional vector is used as the shape feature of the emoticon. In subsequent explanations, we will refer to this feature as ev.

3.2. Distributed Features of Text; dh1, dh2, and dh3

In this study, features are also extracted from the textual sentences with the emoticons. Herein, we obtained features from tweets containing emoticons to be able to extract semantic features that take into account the positions of the emoticons in the text. Various methods have been proposed in the literature for extracting linguistic features from sentences, such as word n-grams, a method using semantic features of words, those that use sentence syntax patterns, and those that use word semantic distribution expressions. In these methods, the sentences are decomposed into certain units and features are extracted thereof. Therefore, in many cases, the positional relationships between the elements in the sentence cannot be used.

In recent years, methods considering the order of appearance of words in a sentence have often been used. For example, the methods using recurrent neural networks that can handle time-series information and a method that can efficiently handle word position information based on transformer and self-attention mechanisms are being used. The natural language model BERT [27] developed by Google in 2018 is a general-purpose model that trains a large-scale network model from large-scale training data by combining transformer and attention. Many methods that improve upon BERT are still being proposed. However, BERT is a very large model, so retraining for dedicated tasks can be costly. When applied to an actual task, it is often finetuned by relearning only the layer close to the output layer using a small amount of task-specific training data.

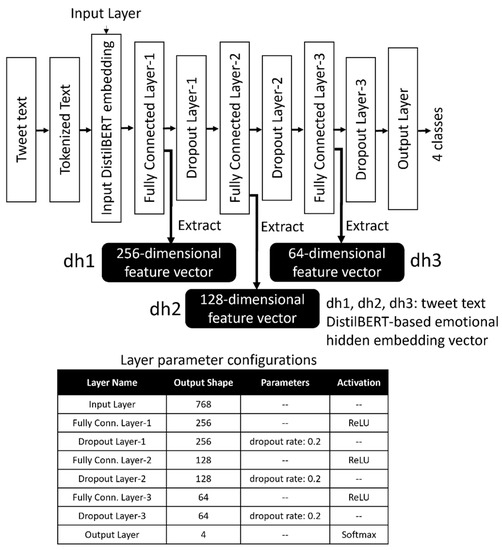

In the present study, we extract features from tweet sentences using DistilBERT [28], which can infer at high speeds without significantly compromising accuracy by reducing the training parameters. In the proposed method, the emotion label classifier is trained by applying distributed expressions obtained from the trained DistilBERT model as the inputs and using the tweet-sentence corpus with emotions labeled by hand as the learning data. Tweet sentences are input to the constructed trained model, and features specialized for emotion estimation are extracted from the three hidden layers. The configuration of the network used is shown in Figure 4, where DistilBERT obtains features with the same number of dimensions (768) as regular BERT. Using this 768-dimensional feature vector as the input, we learn a model that predicts four emotions: “joy”, “anger”, “surprise”, and ”sorrow”. Using this pretrained model, we extract the outputs (256, 128, and 64 dimensions) of the three hidden, fully connected layers, respectively. In the following description, these feature vectors output from the hidden layers are denoted as dh1, dh2, and dh3, respectively.

Figure 4.

Deep neural networks for sentence emotion estimation using DistilBERT-based embedding.

3.3. Emotion Estimation Using Emoticons and Sentences

We combine five types of vectors; namely feature vectors extracted by a CNN feature extractor using face image features as inputs, intermediate vectors obtained through a pretraining model using the distributed representation of DistilBERT extracted from text as the input, and distributed representation using pretrained DistilBERT. These vectors are then fused to build a model that estimates four types of emotions.

In addition, features based on CLCNN and the average vector of the word distributed representations using fastText [29] are used for comparison as baseline features. To combine these features, we use the method of horizontally concatenating each feature vector. The labeled corpus considering both emoticons and sentences is used for the training and evaluation data. The network configuration used for learning is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Deep neural networks for emotion estimation based on emoticons and sentences (using five types of features).

4. Experiment Evaluation

In this section, we evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed method by comparing the proposed method based on the constructed learning model with the baseline method using existing features.

4.1. Dataset

In this experiment, we used a corpus of emoticon images and another corpus of sentences with sentiment labels for pretraining, and a corpus of sentences with emoticon labels for the evaluations. The details regarding the data are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Datasets used for training and evaluation (training:validation = 8:2).

Because the quantity of evaluation data is small, we used five-fold cross-validation to predict and evaluate all examples. Furthermore, as the number of examples is uneven, the synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE) [30] was adopted for oversampling.

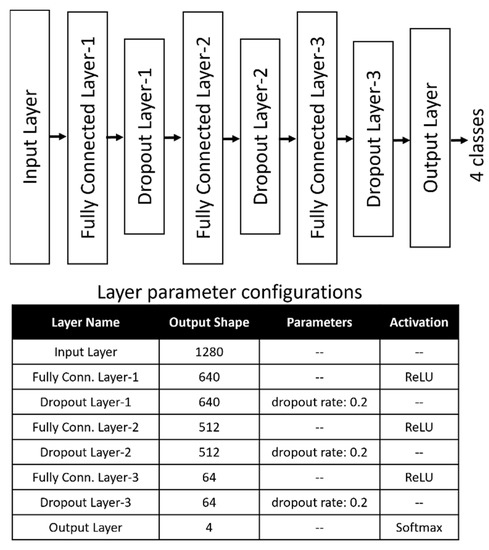

4.2. Baseline Method

Three methods were primarily used as the baseline in this study: a method based on a character-based deep CNN for emoticons, a text classification method based on a distributed representation of words using fastText, and a method that outputs results by combining both of the above methods (mixed method). The character-based CNN comprised two convolutional layers, a maximum pooling layer, and a one-hot vector of up to 15 characters as the input. A model of this network is shown in Figure 4.

For the fastText approach we used the python API, which could also be used for supervised learning of the distributed representations; therefore, when we pretrained a corpus of sentences with emotion labels, we used the emotion labels as the teacher labels. In the following description, we denote the feature extracted using fastText as ft, and the 64-dimensional features extracted from the seventh fully connected layer of the network in Figure 6 as ecv.

Figure 6.

Network configuration of character-level CNN.

4.3. Parameters and Conditions

In this section, we describe the pretraining and training parameters of the experiments. In addition, we compare the case of concatenating the input features by assigning different weights to each feature with the case of assigning uniform weights to each feature. Table 4 shows the parameters of the training models and algorithms. The features used in the evaluation experiments are summarized in Table 5.

Table 4.

Parameters used for pretraining and training.

Table 5.

Features list.

4.4. Results

In this section, we describe the results of our evaluation experiments. In Section 4.4.1, we show the results of the three baseline methods in graph form. In Section 4.4.2, we show the results of the method combining the image features of emoticons with the distributed representation features of the sentences.

4.4.1. Results-1: Baseline Method

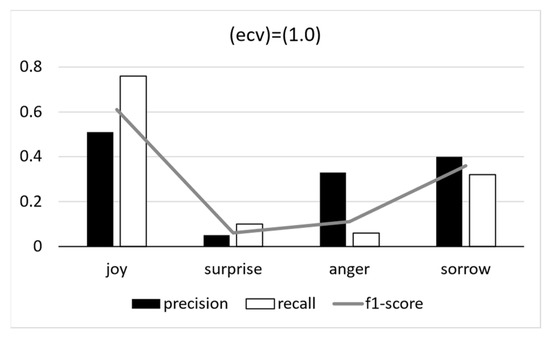

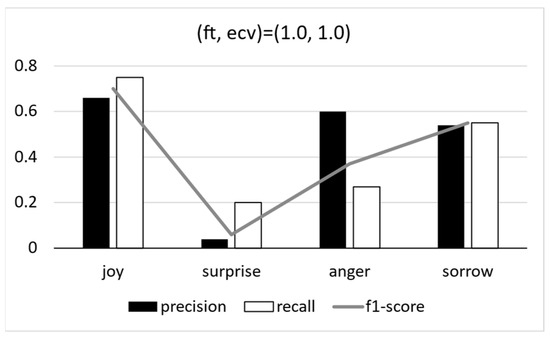

Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9 show the experimental results of the baseline methods using ft, ecv, and combined ft with ecv; these features are presented in Table 4.

Figure 7.

Result of baseline method; (ft) = (1.0).

Figure 8.

Result of baseline method; (ecv) = (1.0).

Figure 9.

Result of baseline method; (ecv) = (1.0).

These results show that using the features of the emoticons in the character units together with the mean vector of word embeddings improves the accuracy of “surprise” estimation compared with that using only one of the features.

4.4.2. Results-2: Proposed Method

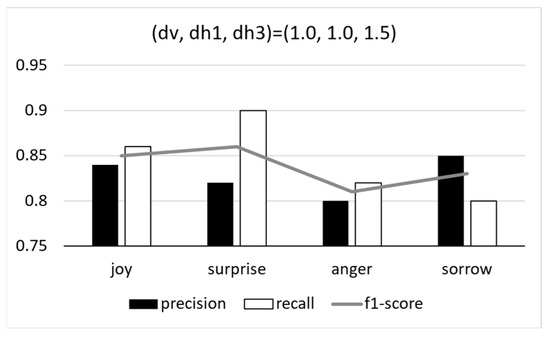

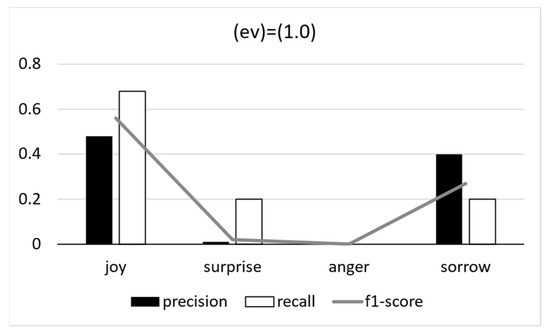

The results for each of the proposed methods are shown in Table 6. The results of the two methods with the highest accuracies and the method with the lowest accuracy are also shown graphically (Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12).

Table 6.

F-score and accuracy (top seven accuracy values).

Figure 10.

Evaluation results; (dv, dh3, ev) = (1.0, 1.5, 0.01).

Figure 11.

Evaluation results; (dv, dh1, dh3) = (1.0, 1.0, 1.5).

Figure 12.

Evaluation results; (ev) = (1.0).

5. Discussion

The experimental results of the proposed method show that the highest accuracy was obtained when three types of features were concatenated: features extracted from the middle layer pretrained with DistilBERT (dh3), distributed representation of DistilBERT, and features extracted from the model pretrained by CNN based on the image features of emoticons. In short sentences such as tweets, we expect that the emotions expressed using only emoticons would be important, but the emotion estimation model trained with the character-level CNNs showed low accuracy for estimating the emotion “anger”.

Focusing only on the number of examples, the number of cases labeled “surprise” was the lowest, and the next lowest was the number of cases labeled “anger”, suggesting that SMOTE, which is an oversampling method, was able to control the effects of sample size bias to some extent. Although there were few examples in which the emoticons had a strong effect on the sentence emotion in the evaluation data used in this study, the addition of features based on the image features of the emoticons resulted in higher accuracies, suggesting that the addition of emoticons’ features had an improvement effect.

Table 7 shows an example of a sentence that was classified correctly using only the proposed method as compared with that using all features with the baseline method. When reading these sentences without considering the emoticons, we felt that these sentences did not include words to express emotions.

Table 7.

Example of sentence classified correctly using only the proposed method.

Therefore, it was difficult to estimate the emotion of the sentence. In such cases, the sentence was assigned an emotion using emoticons. We also considered the reasons why emotions could be correctly estimated with only the proposed method; this was attributed to the fact that using image features could help classify individual emoticons with high accuracies. For sentences that are heavily influenced by the emoticons, we considered that accurately recognizing and classifying the emoticons would result in correct estimation of the emotion of the sentence.

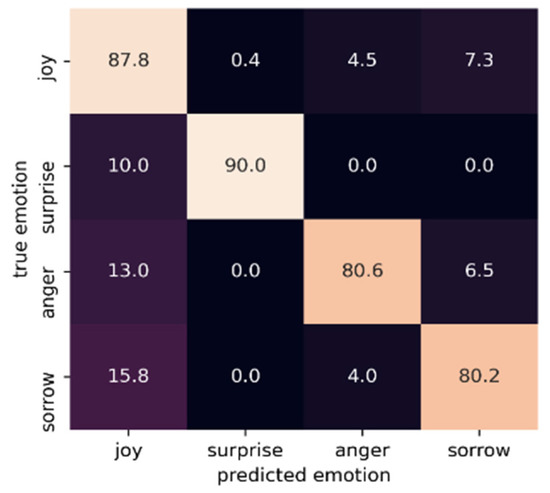

In addition, we considered that the proposed method had a certain improvement effect for accurately recognizing and classifying emoticons. Figure 13 and Figure 14 show the confusion matrices of (dv, hv1, hv2, hv3, ev) and (dv, hv1, hv2, hv3, ecv) generated from the respective results. The horizontal axis is the emotion label estimated by the classifier, and the vertical axis is the correct emotion label. The lighter the color of each cell, the higher is the accuracy. As seen from these figures, the results are better for (dv, hv3, ev) using the image features of emoticons, although their accuracies are almost equal. When training CNNs on images of emoticons, we augmented the training data of the pretraining model and used large-scale data; hence, we were able to create a feature extractor with high versatility. On the other hand, the results show that even when using only a small emoticon dictionary, we can effectively obtain emoticon features.

Figure 13.

Confusion matrix (dv, hv3, ev).

Figure 14.

Confusion matrix (dv, hv1, hv2, hv3, ecv).

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we proposed a more accurate method than existing approaches for estimating emotions from tweets containing emoticons by extracting features from the images of the emoticons, in addition to distributed expressions extracted from the text of the tweets. The effectiveness of the proposed method was confirmed by comparisons with a method using a combination of CLCNN and distributed representation with fastText as the baseline methods.

The results of the evaluation experiments show that the method using a combination of DistilBERT, hidden layer output vector from the pretrained models, and feature expressions extracted from the image features of the emoticons produced the highest accuracy for emotion estimation. We believe that this is because using the images of emoticons enabled a more detailed analysis and capturing of local shape features than existing methods that decompose text at the character level.

On the other hand, if the initial weights for the emoticons are not reduced, the benefit of combining information from them is not available. This suggests that in the case of the evaluation dataset prepared herein, the influence of the emoticons on the overall sentence may have been small for many cases.

To clarify the effects of the emoticons on emotion estimation, we plan to conduct further experiments with sentences wherein the emotions expressed by the emoticons have a higher level of importance (e.g., longer or shorter sentences).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.F. and K.M.; methodology, K.M.; software, K.M.; validation, A.F., K.M. and M.Y.; formal analysis, A.F.; investigation, A.F.; resources, K.M.; data curation, K.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.F.; writing—review and editing, K.M.; visualization, K.M.; supervision, K.K.; project administration, K.M.; funding acquisition, K.M. and M.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by JSPS KAKENHI, grant numbers JP20K12027 and JP21K12141.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fujisawa, A.; Matsumoto, K.; Yoshida, M.; Kita, K. Facial Expression Classification Based on Shape Feature of Emoticons. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Machine Learning and Data Engineering (iCMLDE2017), Sydney, Australia, 20–22 November 2017; pp. 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S.; Zhu, H.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Xing, C.; Chen, H. Emoticon analysis for Chinese social media and e-commerce: The AZEmo system. ACM Trans. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2019, 9, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takishita, S.; Okumura, N. An Extraction of Emoticon based on Documents including Kaomoji and Onomatopeia. In Proceedings of the 77th National Convention of IPSJ, Kyoto, Japan, 17 March 2015; pp. 255–256. (In Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Ptaszynski, M.; Masui, F.; Ishii, N. A method for automatic estimation of meaning ambiguity of emoticons based on their linguistic expressibility. Cogn. Syst. Res. 2020, 59, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, K.; Fujisawa, A.; Yoshida, M.; Kita, K. Emotion recognition of emoticons based on character embedding. J. Softw. 2017, 12, 849–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kwon, J.; Kobayashi, N.; Kamigaito, H.; Takamura, H.; Okumura, M. Bridging Between Emojis and Kaomojis by Learning Their Representations from Linguistic and Visual Information. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/WIC/ACM International Conference on Web Intelligence (WI), Thessaloniki, Greece, 14–17 October 2019; pp. 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Kumamoto, T. Influence of emoticons on the emotions of writers based on their tweets—Focusing on writers’ emotions inferred by readers. Trans. Jpn. Soc. Kansei Eng. 2019, 19, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegrzyn-Wolska, K.M.; Bougueroua, L.; Yu, H.; Zhong, J. Explore the Effects of Emoticons on Twitter Sentiment Analysis. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Computer Science & Engineering, Sydney, Australia, 23–24 December 2016; pp. 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, M.A.; Marium, S.M.; Begum, S.A.; Dipa, N.S. An algorithm and method for sentiment analysis using the text and emoticon. ICT Express 2020, 6, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiritchenko, S.; Zhu, X.; Mohammad, S.M. Sentiment analysis of short informal texts. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2014, 50, 723–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahanin, Z.; Ismail, M.A. Feature extraction based on fuzzy clustering and emoji embeddings for emotion classification. Int. J. Technol. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2020, 2, 102–112. [Google Scholar]

- Cherbonnier, A.; Michinov, N. The recognition of emotions beyond facial expressions: Comparing emoticons specifically designed to convey basic emotions with other modes of expression. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 118, 105589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujino, N.; Matsumoto, K.; Yoshida, M.; Kita, K. Emotion estimation adapted to gender of user based on deep neural networks. Int. J. Adv. Intell. IJAI 2018, 10, 121–133. [Google Scholar]

- Eisner, B.; Rocktschel, T.; Augenstein, I.; Bošnjak, M.; Riedel, S. Emoji2vec: Learning Emoji Representations from their Description. In Proceedings of the 4th International Workshop on Natural Language Processing for Social Media at EMNLP, New York, NY, USA, 9–15 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Rzepka, R.; Ptaszynski, M.; Araki, K. Emoticon-Aware Recurrent Neural Network Model for Chinese Sentiment Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2018 9th International Conference on Awareness Science and Technology (iCAST), Fukuoka, Japan, 19–21 September 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Chen, L.; Guo, B.; Li, W. Featuring, detecting, and visualizing human sentiment in Chinese micro-blog. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data 2016, 10, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhai, C.; Rongrong, J.; Jinsong, S.; Donglin, C.; Yue, G. Predicting microblog sentiments via weakly supervised multimodal deep learning. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2017, 20, 997–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Riza, V.; Tugb, Y.; Savas, Y. Sentiment Analysis Using Learning Approaches Over Emojis for Turkish Tweets. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Computer Science and Engineering (UBMK), Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 20–23 September 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegdan, A.H.; Yahya, M.T.; Mahmod, A.; Mohammed, N.A. Are Emoticons Good Enough to Train Emotion Classifiers of Arabic Tweets. In Proceedings of the 2016 7th International Conference on Computer Science and Information Technology (CSIT), Amman, Jordan, 13–14 July 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, F.; Qion, T.; Ji, D. Emoji-based sentiment analysis using attention networks. ACM Trans. Asian Low-Resour. Lang. Inf. Process. 2020, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Cao, Y.; Yao, H.; Lu, X.; Peng, X.; Mei, H.; Liu, X. Emoji-powered sentiment and emotion detection from software developers’ communication data. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2021, 30, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiremath, S.; Manjula, S.H.; Venugopal, K.R. Unsupervised Sentiment Classification of Twitter Data using Emoticons. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Emerging Smart Computing and Informatics (ESCI), Pune, India, 5–7 March 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the NIPS 2012, Reno, NV, USA, 3–8 December 2012. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, J.; LeCun, Y. Character-level convolutional networks for text classification. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2015, 28, 649–657. [Google Scholar]

- Saxe, J.; Berlin, K. eXpose: A character-level convolutional neural network with embeddings for detecting malicious URLs, file paths and registry keys. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1702.08568. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, Y.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the NAACL-HLT 2019, Minneapolis, MI, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Sanh, V.; Debut, L.; Chaumond, J.; Wolf, T. DistilBERT: A distilled version of BERT: Smaller, faster, cheaper and lighter. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.01108. [Google Scholar]

- Joulin, A.; Grave, E.; Bojanowski, P.; Mikolov, T. Bag of Tricks for Efficient Text Classification. In Proceedings of the 15th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Valencia, Spain, 3–7 April 2017; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: Synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2002, 16, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).