The Use of Collaborative Practices for Climate Change Adaptation in the Tourism Sector until 2040—A Case Study in the Porto Metropolitan Area (Portugal)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Adaptation of Urban Tourism to Climate Change Based on Policy-Making Trends Emerging during the COVID-19 Period

3. Methods and Data

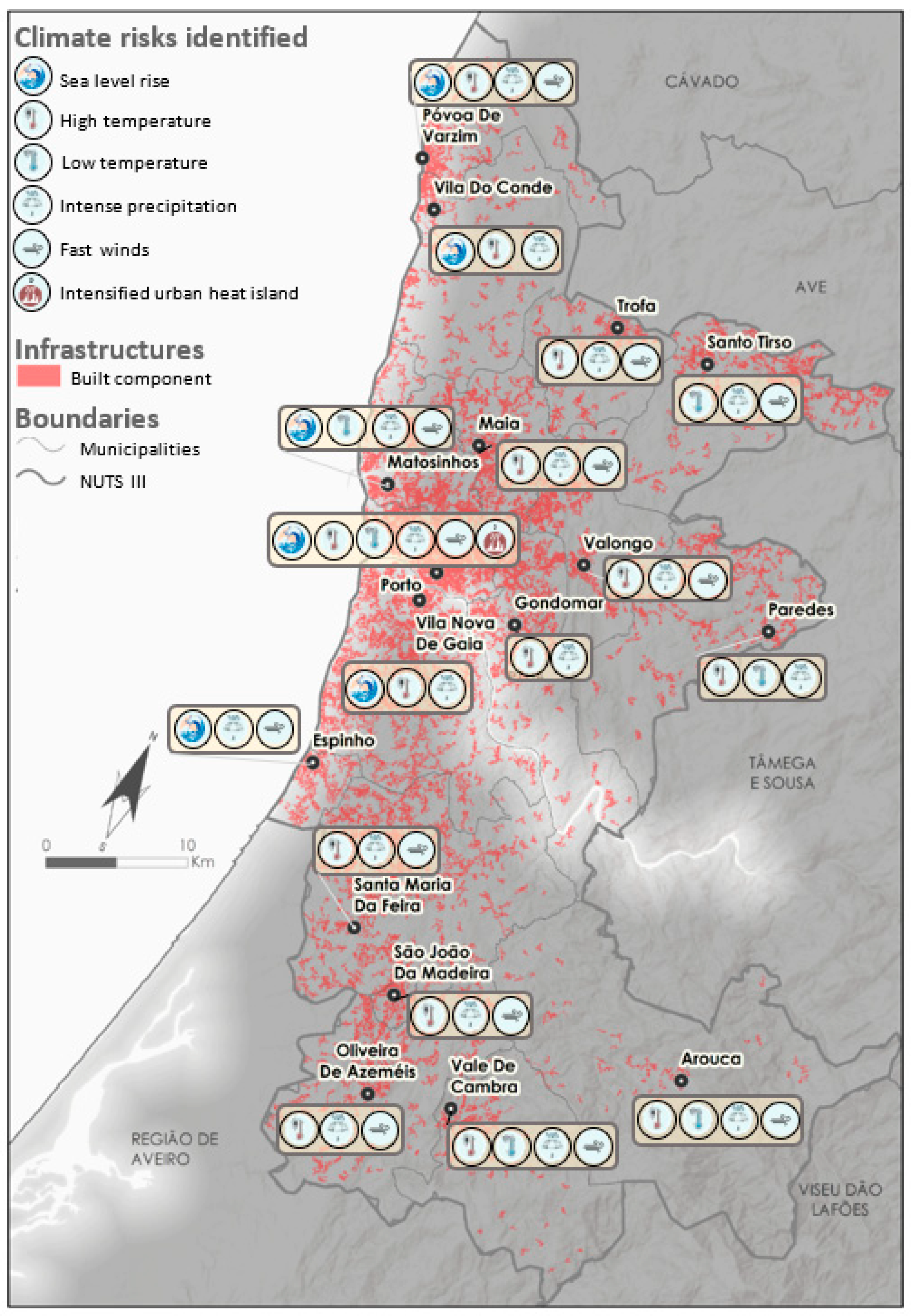

3.1. Study Area

- (a)

- Increase in the number of hot days (between 23 to 62 days) and very hot days (between 5 to 15 days);

- (b)

- Higher frequency of heat waves and increased temporal duration;

- (c)

- Increase in the number of tropical nights, which can reach 21 nights;

- (d)

- Increase of 5 days per year of drought for each increase of 100 ppm of CO2.

3.2. The Use of Participatory-Based Methodologies

- (i)

- The opinion of undergraduate students in Geography and Planning, from the University of Minho (Portugal), about tourism strategies for coping with climate change.

- (ii)

- The views of experts on tourism, town planning, and climate change regarding important decisions as well as a strategy closer to the needs of the territory through a Modified Delphi Approach (MDA);

- (iii)

- A workshop with a view to design a final strategy to be delivered to decision-makers.

- (1)

- The diagnosis—where a survey of the particularities of the territory under analysis was made;

- (2)

- The assessment—which has been considered a key element in the establishment of research priorities and potential measures since the start;

- (3)

- The dissemination practices—building solutions for territorial context, based on measures and actions to be developed to cope with climate change.

3.2.1. Strategies Design Based on the Opinion of Undergraduate Students in Geography and Planning

- What can be done in the short-term?

- What innovative solutions can be developed?

- How do they mitigate the effects of climate change? And how to improve the thermal comfort of those who visit the urban destination?

- The students also considered the following objectives for the purposes of the method:

- Identify the positive and negative aspects of urban tourism;

- Assess the comfort of public space to be used by tourists;

- Point out some solutions to mitigate the negative aspects of tourism in a climate change framework.

3.2.2. Delphi’s Approach to Addressing Climate Change Challenges

3.2.3. The Workshop as the Final Stage of Research—The Launch of an Intervention Agenda for Urban Tourism

- (1)

- Two were online sessions about the impacts of climate change on urban tourism in the Mediterranean and the need of public policies, as well as a communication agenda to address the problem;

- (2)

- One was an in-person session, with all relevant issues being discussed in a ‘World Café’ (Appendix D).

- (i)

- Identify good practices developed at international level;

- (ii)

- Analyze the results of research carried out in PMA;

- (iii)

- Contribute to innovative tourism solutions capable of fostering guidelines for urban design in areas of growth and priority of action for the bioclimatic rehabilitation of public space in a climate change context.

4. Results

4.1. First Contributions to the Definition of the Strategy—The Territorial Dimension

- (i)

- Physical–natural conditions—oceanic proximity and weather conditions favorable to the elimination of the effect of pollutants; proximity to natural parks and other green areas;

- (ii)

- Economic conditions—the existence of good economic indicators associated with the growth of the tourism sector in PMA; although there is a decline in the tourism sector due to COVID-19, adaptation and resilience measures in the tourism sector can reduce the consequences caused by the pandemic;

- (iii)

- Sociodemographic and housing conditions—young people predominate in age groups, contributing to increased public awareness of climate change and mitigation measures;

- (iv)

- Political–sectoral conditions—the articulation capacity between the mayors of the different municipalities in various matters of community interest and in a framework of interaction between several institutional figures and sectoral entities is not to be neglected.

4.2. Identification of Problems, Opportunities and Potential Measures Related to Climate Change—The Intervention of Experts and Stakeholders

- (1)

- Disseminate knowledge on sustainable solutions for the adaptation of urban tourism to climate change;

- (2)

- Build evidence-based strategies with a focus on specific and achievable objectives;

- (3)

- Put the need for adaptation to climate change on the urban tourism agenda (which includes training, public policies, public–private partnerships, licensing of activities and tourism scrutiny);

- (4)

- Define criteria and recovery systems for the recognition of good practices and recapitalization of organizations with funds for climate resilience;

- (5)

- Promote projects that integrate local communities and tourists and ensure the return of social, cultural, economic, and environmental capital, motivating tourism among the community (not necessarily tourist promoters);

- (6)

- Educate for active citizenship and climate literacy;

- (7)

- Control mass tourism, polluting transport, and the effects of seasonality on tourism activity (controlling peaks and low seasons);

- (8)

- Activate empowerment of tourism stakeholders (where tourists are included) as climate change mitigating agents.

4.3. Practical Dissemination of the Proposed Lines of Action for Urban Tourism—The Proposal

- (1)

- The lack of subsidiarity between policy instruments and climate action, namely, between regional, sub-regional and local scale;

- (2)

- The absence of a scale-up of adaptation and mitigation policies and strategies in the urban and city operations domain; and

- (3)

- The late action in solving problems related to climate change, namely, when the risk is communicated and how it reaches the players (e.g., climate resilience of local communities).

- (1)

- Scheduling activities—in case weather and climate conditions are favorable, programming can be intensified, especially in the short term, through the provision of activities and complementary products; if conditions are not favorable, programming should be reconsidered by outlining several alternatives;

- (2)

- Marketing and promotional campaigns—once again, in case of favorable conditions, it is necessary to further promote the destination, with the inclusion of weather forecasts; in case of adverse weather conditions the promotional planning strategy should be changed in the medium and long term; bear in mind that planning should be changed in a period no shorter than 5 years, and no longer than 30 years;

- (3)

- Economy growth (employment and services)—depending on the conditions, it will be possible to generate jobs and services, or the offer will have to be redirected with adjustments in staff service and provisioned offer;

- (4)

- Adaptation, mitigation, and resilience plan—under beneficial conditions to cope with climate change adaptation, preventive measures that are granted to this purpose should be made; nevertheless, in unfavorable situations it will be useful to implement an emergency plan (set up a priori, with assessment and monitoring of resources over time, resilience in the face of damage).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Main Conclusions

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

- (1)

- A holistic assessment is essential to address other sectors directly or indirectly related (e.g., transport, agriculture, and energy); in addition, more information on the impacts of climate change on urban tourism is needed during the various seasons;

- (2)

- There are still not enough innovative services capable of translating and adapting complex climate information from decision-makers to decision-making related to urban tourism; market and feasibility studies of the measures, with guidance on how to interpret the results and how to prepare and adapt to climate change can benefit the destination;

- (3)

- We should work the several data from this research to account for the effects of some of the measures, solutions and resources identified;

- (4)

- New workshops should be held, bringing together the academic community, politicians and decision-makers, municipal council technicians, tourism company workers and members of the civil community; previous insights into the review and application of methodologies have already been validated and other requirements and needs of end-users (tourists) have been discussed, but this approach deserves continuous adaptation;

- (5)

- Creation of a web platform where the data resulting from this research project is disseminated and fed with other additional initiatives.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

Appendix D

Appendix E

References

- IPCC. AR6 Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis-Working Group I contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, G.A.; Vargas-Chaves, I. Participation in environmental decision making as an imperative for democracy and environmental justice in Colombia. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2018, 9, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meisch, S.P.; Bremer, S.; Young, M.T.; Funtowicz, S.O. Extended Peer Communities: Appraising the contributions of tacit knowledges in climate change decision-making. Futures 2022, 135, 102868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Hove, S. Participatory approaches to environmental policy-making: The European Commission Climate Policy Process as a case study. Ecol. Econ. 2000, 33, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, H.; Remoaldo, P.C.; Ribeiro, V.; Martín-Vide, J. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Tourist Risk Perceptions—The Case Study of Porto. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depledge, J.; Saldivia, M.; Peñasco, C. Glass half full or glass half empty: The 2021 Glasgow Climate Conference. Clim. Policy 2022, 22, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFRC. 2018 World Disasters Report: Leaving No One behind; IFRC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Whyte, W.H. The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces; Academia: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J. Life between Buildings; Van Nostrand Reinhold; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1987; Volume 23. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J. A Vida Entre Edifícios: Usando o Espaço Público; Livraria Tigres de Papel: Lisboa, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, M. Place value: Place quality and its impact on health, social, economic and environmental outcomes. J. Urban Des. 2019, 24, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kakderi, C.; Komninos, N.; Panori, A.; Oikonomaki, E. Next City: Learning from Cities during COVID-19 to Tackle Climate Change. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A.; Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R. The COVID-19 pandemic: Impacts on cities and major lessons for urban planning, design, and management. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 749, 142391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honey-Rosés, J.; Anguelovski, I.; Chireh, V.K.; Daher, C.; Konijnendijk van den Bosch, C.; Litt, J.S.; Mawani, V.; McCall, M.K.; Orellana, A.; Oscilowicz, E. The impact of COVID-19 on public space: An early review of the emerging questions–design, perceptions and inequities. Cities Health 2020, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amundsen, H.; Berglund, F.; Westskog, H. Overcoming barriers to climate change adaptation—a question of multilevel governance? Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2010, 28, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penning-Rowsell, E.; Johnson, C.; Tunstall, S. ‘Signals’ from pre-crisis discourse: Lessons from UK flooding for global environmental policy change? Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urwin, K.; Jordan, A. Does public policy support or undermine climate change adaptation? Exploring policy interplay across different scales of governance. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2008, 18, 180–191. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.W.; Rowan, B. Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 83, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martínez-Ibarra, E. Tipos de tiempo para el turismo de sol y playa en el litoral alicantino. Estud. Geográficos 2008, 69, 135–155. [Google Scholar]

- Susskind, L.; Kim, A. Building local capacity to adapt to climate change. Clim. Policy 2021, 22, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriopedro, D.; Fischer, E.M.; Luterbacher, J.; Trigo, R.M.; García-Herrera, R. The hot summer of 2010: Redrawing the temperature record map of Europe. Science 2011, 332, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Giorgi, F.; Coppola, E. Does the model regional bias affect the projected regional climate change? An analysis of global model projections. Clim. Change 2010, 100, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoerling, M.; Eischeid, J.; Perlwitz, J.; Quan, X.; Zhang, T.; Pegion, P. On the increased frequency of Mediterranean drought. J. Clim. 2012, 25, 2146–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ng, E. Policies and technical guidelines for urban planning of high-density cities–air ventilation assessment (AVA) of Hong Kong. Build. Environ. 2009, 44, 1478–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, C.; Honrado, J.P.; Cerejeira, J.; Sousa, R.; Fernandes, P.M.; Vaz, A.S.; Alves, M.; Araújo, M.; Carvalho-Santos, C.; Fonseca, A. On the development of a regional climate change adaptation plan: Integrating model-assisted projections and stakeholders’ perceptions. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 805, 150320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J.; Gordon, I.J. Adaptive heritage: Is this creative thinking or abandoning our values? Climate 2021, 9, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, H.; Remoaldo, P.C.; Ribeiro, V.; Martín-Vide, J. Perceptions of human thermal comfort in an urban tourism destination—A case study of porto (Portugal). Build. Environ. 2021, 205, 108246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Lopes, H.; Remoaldo, P.; Sánchez-Fernández, M.D.; Ribeiro, J.C.; Silva, S.; Ribeiro, V. The Role of Residents and Their Perceptions of the Tourism Industry in Low-Density Areas: The Case of Boticas, in the Northeast of Portugal. In The Impact of Tourist Activities on Low-Density Territories; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 203–225. [Google Scholar]

- Geneletti, D.; Zardo, L. Ecosystem-based adaptation in cities: An analysis of European urban climate adaptation plans. Land Use Policy 2016, 50, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berke, P.; Kates, J.; Malecha, M.; Masterson, J.; Shea, P.; Yu, S. Using a resilience scorecard to improve local planning for vulnerability to hazards and climate change: An application in two cities. Cities 2021, 119, 103408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. URBAN ACUPUNCTURE Transforming Vacant Urban Spaces for Community Gathering Suwon, South Korea. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Washington, Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.D.; Farmer, J.R.; Dickinson, S.L.; Robeson, S.M.; Fischer, B.C.; Reynolds, H.L. Climate change impacts and urban green space adaptation efforts: Evidence from US municipal parks and recreation departments. Urban Clim. 2021, 39, 100962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.P.; De Sousa, J.F.; Silva, M.M.; Nouri, A.S. Climate change adaptation and urbanism: A developing agenda for Lisbon within the twenty-first century. Urban Des. Int. 2014, 19, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Onete, M.; Pop, O.G.; Gruia, R. Plants as indicators of environmental conditions of urban spaces from central parks of Bucharest. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2010, 9, 1639–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Önder, D.E.; Gigi, Y. Reading urban spaces by the space-syntax method: A proposal for the South Haliç Region. Cities 2010, 27, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Molina, A.; Williamson, K.; Dupont, W. Thermal Comfort Assessment of Stone Historic Religious Buildings in A Hot and Humid Climate During Cooling Season. A Case Study. Energy Build. 2022, 262, 111997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.P. Urbanismo e Adaptação às Alterações Climáticas: As Frentes de Água; Livros Horizonte: Lisbon, Portugal, 2013; ISBN 9722417673. [Google Scholar]

- Nouri, A.S.; Costa, J.P. Addressing thermophysiological thresholds and psychological aspects during hot and dry mediterranean summers through public space design: The case of Rossio. Build. Environ. 2017, 118, 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Project for Public Spaces. How to Turn a Place Around: A Handbook for Creating Successful Public Spaces; Project for Public Spaces Incorporated: New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 0970632401. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 052543285X. [Google Scholar]

- Nouri, A.S.; Costa, J.P. Placemaking and climate change adaptation: New qualitative and quantitative considerations for the “Place Diagram”. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2016, 10, 356–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- INE População Residente (N.°) por Local de Residência (Resultados Preliminares Censos 2021) e Sexo; Decenal-INE, Recenseamento da População e Habitação-Censos 2021. Available online: https://ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_indicadores&indOcorrCod=0010745&contexto=pi&selTab=tab0 (accessed on 21 February 2022).

- Yasmeen, R. Top 100 City Destination: 2019 Edition; Euromonitor Internacional: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, A.; Madureira, H.; Fonseca, L.; Gonçalves, P. METROCLIMA: Plano Metropolitano de Adaptação às Alterações Climáticas-Área Metropolitana do Porto; Área Metropolitana do Porto: Porto, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2013-The Physical Science Basis; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 1542, pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- IPCC. Global Warming of 1.5 C; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jevrejeva, S.; Moore, J.C.; Grinsted, A. Sea level projections to AD2500 with a new generation of climate change scenarios. Glob. Planet. Change 2012, 80, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, H.; Remoaldo, P.; Silva, M.; Ribeiro, V.; Vide, J.M. Climate in tourism’s research agenda: Future directions based on literature review. Boletín Asoc. Geógrafos Españoles 2021, 90, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, H.S.; Remoaldo, P.; Ribeiro, V.; Martín-Vide, J. Análise do Ambiente Térmico Urbano e Áreas Potencialmente Expostas ao Calor Extremo no município do Porto (Portugal). Cuad. Geogr. Rev. Colomb. Geogr. 2022, 31, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Stringer, E.T.; Aragón, A.O. Action Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2020; ISBN 1544355912. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, L. The impact of paper versus digital map technology on students’ spatial thinking skill acquisition. J. Geogr. 2018, 117, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, C.P.; Oberle, A.; Sugumaran, R. Implementing a high school level geospatial technologies and spatial thinking course. J. Geog. 2011, 110, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalkey, N.C. The Delphi Method: An Experimental Study of Group Opinion; RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Garrod, B. Understanding the relationship between tourism destination imagery and tourist photography. J. Travel Res. 2009, 47, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrod, B.; Fyall, A. Revisiting Delphi: The Delphi Technique in Tourism Research. In Tourism Research Methods: Integrating Theory with Practice; CABI International: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kattirtzi, M.; Winskel, M. When experts disagree: Using the Policy Delphi method to analyse divergent expert expectations and preferences on UK energy futures. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 153, 119924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, C.O.; Santos, N. Tourism qualitative forecasting scenario building through the Delphi Technique. Cuad. Tur. 2020, 46, 423–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeller, G.H.; Shafer, E.L. The Delphi technique: A tool for long-range tourism and travel planning. In Travel, Tourism, and Hospitality Research. A Handbook for Managers and Researchers; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 417–424. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Xi, Z. Application of Delphi method in screening of indexes for measuring soil pollution value evaluation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 6561–6571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Bergner, N.M.; Lohmann, M. Future challenges for global tourism: A Delphi survey. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baláž, V.; Dokupilová, D.; Filčák, R. Participatory multi-criteria methods for adaptation to climate change. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2021, 26, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, C.O. Turismo, Território e Desenvolvimento: Competitividade e Gestão Estratégica de Destinos; Universidade de Coimbra: Coimbra, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- De Loe, R.C. Exploring complex policy questions using the policy Delphi: A multi-round, interactive survey method. Appl. Geogr. 1995, 15, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Loë, R.C.; Melnychuk, N.; Murray, D.; Plummer, R. Advancing the state of policy Delphi practice: A systematic review evaluating methodological evolution, innovation, and opportunities. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2016, 104, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiko, A. Consensus measurement in Delphi studies: Review and implications for future quality assurance. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2012, 79, 1525–1536. [Google Scholar]

- Sossa, J.W.Z.; Halal, W.; Zarta, R.H. Delphi method: Analysis of rounds, stakeholder and statistical indicators. Foresight 2019, 21, 525–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Travel Comission Tourism and Climate Change Mitigation-Embracing the Paris Agreement; European Travel Commission: Bruxelas, Belgium, 2018.

- Lerner, J. Urban Acupuncture; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; ISBN 1610915836. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal, D.G.; Fernandes, C.O.; Viterbo, L.M.F.; Vilaça, H.; Barros, N.; Maia, R.L. Combining an evaluation grid application to assess ecosystem services of urban green spaces and a socioeconomic spatial analysis. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2021, 28, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, D.G.; Dias, R.C.; Teixeira, C.P.; Fernandes, C.O.; Filho, W.L.; Barros, N.; Maia, R.L. Clustering public urban green spaces through ecosystem services potential: A typology proposal for place-based interventions. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 132, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; de Freitas, C.; Matzarakis, A. Adaptation in the Tourism and Recreation Sector. In Biometeorology for Adaptation to Climate Variability and Change; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 171–194. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, H.; Remoaldo, P.; Ribeiro, V.; Martín-Vide, J. Pathways for adapting tourism to climate change in an urban destination–Evidences based on thermal conditions for the Porto Metropolitan Area (Portugal). J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 315, 115161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, F.; Lopes, A.; Ambrósio, V. Tourists’ Perceptions on Climate Change in Lisbon Region. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patterson, J.J. More than planning: Diversity and drivers of institutional adaptation under climate change in 96 major cities. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2021, 68, 102279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madureira, H.; Monteiro, A.; Cruz, S. Where to Go or Where Not to Go—A Method for Advising Communities during Extreme Temperatures. Climate 2021, 9, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madureira, H.; Pacheco, M.; Sousa, C.; Monteiro, A.; De’-Donato, F.; De-Sario, M. Evidences on adaptive mechanisms for cardiorespiratory diseases regarding extreme temperatures and air pollution: A comparative systematic review. Geogr. Sustain. 2021, 2, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Câmara Municipal do Porto. ClimAdaPT. Local-Estratégia Municipal de Adaptação às Alterações Climáticas do Porto; Câmara Municipal do Porto: Porto, Portugal, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Valls, J.; Sardá, R. Tourism expert perceptions for evaluating climate change impacts on the Euro-Mediterranean tourism industry. Tour. Rev. 2009, 64, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiricka-Pürrer, A.; Brandenburg, C.; Pröbstl-Haider, U. City tourism pre-and post-COVID-19 pandemic–Messages to take home for climate change adaptation and mitigation? J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2020, 31, 100329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megahed, N.A.; Ghoneim, E.M. Antivirus-built environment: Lessons learned from Covid-19 pandemic. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 61, 102350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; Gössling, S.; de Freitas, C.R. Preferred climates for tourism: Case studies from Canada, New Zealand and Sweden. Clim. Res. 2008, 45, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jopp, R.; DeLacy, T.; Mair, J.; Fluker, M. Using a regional tourism adaptation framework to determine climate change adaptation options for Victoria’s Surf Coast. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 18, 144–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eriksen, S.H.; Nightingale, A.J.; Eakin, H. Reframing adaptation: The political nature of climate change adaptation. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 35, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, G. What makes climate change adaptation effective? A systematic review of the literature. Glob. Environ. Change 2020, 62, 102071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemonsu, A.; Viguié, V.; Daniel, M.; Masson, V. Vulnerability to heat waves: Impact of urban expansion scenarios on urban heat island and heat stress in Paris (France). Urban Clim. 2015, 14, 586–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandy, W.R.; Rogerson, C.M. Urban tourism and climate change: Risk perceptions of business tourism stakeholders in Johannesburg, South Africa. Urbani Izziv. 2019, 30, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteucci, X.; Nawijn, J.; von Zumbusch, J. A new materialist governance paradigm for tourism destinations. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 30, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeppel, H. Collaborative governance for low-carbon tourism: Climate change initiatives by Australian tourism agencies. Curr. Issues Tour. 2012, 15, 603–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamukcu-Albers, P.; Ugolini, F.; La Rosa, D.; Grădinaru, S.R.; Azevedo, J.C.; Wu, J. Building green infrastructure to enhance urban resilience to climate change and pandemics. Landsc. Ecol. 2021, 36, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willems, J.J.; Kenyon, A.V.; Sharp, L.; Molenveld, A. How actors are (dis) integrating policy agendas for multi-functional blue and green infrastructure projects on the ground. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2021, 23, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Lacueva, R.; Velasco Gonzalez, M. Policy coherence between tourism and climate policies: The case of Spain and the Autonomous Community of Catalonia. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1708–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Climatic Variable | Tendency | Projected Changes | Influence on the Tourism Sector (Level and Direction) |

|---|---|---|---|

Temperature  |  Annual average temperature rise, in particular

Annual average temperature rise, in particularmaximum temperatures | Annual and seasonal average Annual average temperature rise, between 1 °C and 4 °C at the end of the century. Significant increase in Tmax in autumn (between 1.3 °C and 3.6 °C) and summer (between 1.3 °C and 4.1 °C). Very hot days Increase in the number of days with very high temperatures (≥35 °C) and tropical nights, with minimum temperatures ≥20 °C. Heat waves More frequent and intense heat waves. | Level  |

Direction  | |||

Precipitation  |  Annual average precipitation decrease Annual average precipitation decrease(increase in droughts and decrease in water reserves) | Annual and seasonal average Decrease in annual average rainfall at the end of the 21st century, ranging from 5.0% to 12%. In the winter months, the trend is for a slight increase in precipitation, ranging from 0.0% to 17.0%. In the remaining intra-anual period, a decrease is expected, which can vary between 9.0% and 25.0% in spring, between 13.0% and 51.0% in summer and between 14.0% and 22.0% in autumn. Most frequent and intense droughts Decrease in the number of days with precipitation, between 11 and 25 days per year. Increased frequency and intensity of droughts in southern Europe [1,45,46] [IPCC, 2014; 2018; 2021]. | Level  |

Direction  | |||

Sea rise  |  Average seawater level rise Average seawater level rise | Average Average sea level increase between 0.17 m and 0.38 m for 2050, and between 0.26 and 0.82 by the end of the 21st century (global projections) [45]. Other authors indicate an increase that could reach 1.10 m in 2100 (global projections) [47]. Extreme events Average sea level rise with more severe impacts, when combined with the rise in sea level associated with storms (storm surge). | Level  |

Direction  | |||

Extreme events  |  Increase in extreme precipitation phenomena Increase in extreme precipitation phenomena | Extreme events An increase in two extreme phenomena, in particular, intense or very intense precipitation (results evidenced in national projections—Soares et al., 2015), with consequences on the fast and intense floods (mainly by the location on the coast and next to riverside areas—e.g., Ribeira do Porto). More intense winter storms, accompanied by rain and strong wind. | Level  |

Direction  |

Decrease,

Decrease,  Increase; Level: Little

Increase; Level: Little  Very much; Direction:

Very much; Direction:  Positive,

Positive,  Negative. Source: Authors’ own elaboration, considering the various Municipal Strategies for Adaptation to Climate Change (EMAAC) of the Porto Metropolitan Area (PMA).

Negative. Source: Authors’ own elaboration, considering the various Municipal Strategies for Adaptation to Climate Change (EMAAC) of the Porto Metropolitan Area (PMA).| Topic | Brief Description | Phase | Basic Collaborative Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elements of adaptation in study area | Establish the conditions of the study area to address climate change and concerns around tourism. To be included: 1—The relevance of the consideration of urban tourism as a critical factor for local climate resilience. 2—Local examples. 3—Experts selected to guide the planning process (theoretical sessions with case studies presented). | Diagnosis | Opinions of undergraduate students in Geography and Planning, from the University of Minho. |

| Introduction to the planning structure | Introduction to the planning structure by guiding participants through an active process for identifying tourism resources and preparing a plan to protect local resources. | Diagnosis | Opinions of undergraduate students in Geography and Planning, from the University of Minho. Delphi panel with experts on tourism, town planning, and climate change. |

| Identify tourism resources in the study area | Characteristics and identification of existing resources important for adaptation to climate change. | Diagnosis | Opinions of undergraduate students in Geography and Planning, from the University of Minho. |

| Involvement of Stakeholders | Identification of relevant stakeholders to meet the challenge of climate change in the tourism sector. | Diagnosis | Opinions of undergraduate students in Geography and Planning, from the University of Minho. |

| Vulnerability assessment of identified tourism resources | Identification of the basic components of vulnerability, types of assessment and how they are used to address climate change. | Assessment | Delphi panel with experts on tourism, town planning, and climate change. |

| Definition of a mitigation, adaptation and resilience plan in the face of changes | Application of the planning process to protect resources. The process includes prioritizing actions, developing an implementation plan, and making commitments for implementation progress. Setting the agenda for intervention. | Assessment and pratical dissemination | Delphi panel with experts on tourism, town planning, and climate change workshop and final strategy to be delivered to decision-makers. |

| Variables | Features | Round 1 (n = 47) Type: Relevance and Preparation | Round 2 (n = 35) Type: Priority and Predictability | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Gender | Male | 30 | 63.8 | 18 | 51.4 |

| Female | 17 | 36.2 | 17 | 48.6 | |

| Education | Degree | 7 | 14.9 | 5 | 14.3 |

| Master’s | 4 | 8.5 | 3 | 8.6 | |

| Doctorate | 36 | 76.6 | 27 | 77.1 | |

| Age | 25–34 | 6 | 12.8 | 5 | 14.3 |

| 35–44 | 5 | 10.6 | 3 | 8.6 | |

| 45–54 | 19 | 40.4 | 14 | 40.0 | |

| 55–64 | 15 | 31.9 | 12 | 34.3 | |

| ≥65 | 2 | 4.3 | 1 | 2.9 | |

| Work experience (in years) | ≤5 | 3 | 6.4 | 3 | 8.6 |

| 6–10 | 8 | 17.0 | 6 | 17.1 | |

| 11–15 | 4 | 8.5 | 3 | 8.6 | |

| 16–20 | 10 | 21.3 | 9 | 25.7 | |

| 21–25 | 12 | 25.5 | 8 | 22.9 | |

| 26–30 | 4 | 8.5 | 2 | 5.7 | |

| >30 | 6 | 12.8 | 4 | 11.4 | |

| Type of employment | University | 36 | 76.6 | 27 | 77.1 |

| Government | 5 | 10.6 | 4 | 11.4 | |

| NGO | 2 | 4.3 | 1 | 2.9 | |

| Companies and businesses | 4 | 8.5 | 3 | 8.6 | |

| Measure | Priority of Action | Stakeholders Enrolled | Measurement Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short term(in 2/3 years) | |||

| Restrict building in areas susceptible to collapse with potential damage to people and property. | Level 1 (Top Priority) | Public administration | Regulatory |

| Mapping of climate risk areas. | Level 1 (Top Priority) | Public administration | Regulatory |

| Use more sustainable tourism practices. | Level 1 (Top Priority) | Tourists and visitors | Soft and Market oriented |

| Assess the carrying capacity of sensitive areas—urban and natural areas (e.g., management of tourist movements/entries (in monuments,…)). | Level 2 (High Priority) | Tourists and visitors | Soft |

| Promote the use of soft modes during the visit (e.g., bicycle use). | Level 2 (High Priority) | Tourists and visitors | Soft and Market oriented |

| Incentives to change the energy system. | Level 2 (High Priority) | Local community | Soft |

| Medium term(until 2030) | |||

| Planning depending on the carrying capacity. | Level 1 (Top Priority) | Public administration | Regulatory |

| Increase and improvement of public transport. | Level 1 (Top Priority) | Public administration | Soft and regulamentar |

| Expansion and improvement of pedestrian network and provision of cycle paths. | Level 1 (Top Priority) | Public administration | Soft and regulamentar |

| Privileging the maintenance and/or implementation of permeable surfaces through NBS (Nature Based Solutions). | Level 2 (High Priority) | Public administration | Soft and regulamentar |

| Creating new regulations for urban areas that promote more sustainable practices. | Level 2 (High Priority) | Public administration | Regulatory |

| Adapt urban spaces according to environmental indicators. | Level 2 (High Priority) | Public administration | Regulatory |

| Encourage stakeholders’ participation in adaptation measures from the early stage of the planning process. | Level 2 (High Priority) | Public administration | Soft |

| Promote the use of electric vehicles, bicycles, and soft modes among tourists. | Level 2 (High Priority) | Public administration | Soft |

| Make the use of renewable energy a priority. | Level 1 (Top Priority) | Tourism sector companies | Regulatory |

| Introduce circular practices in the management of water cycle. | Level 1 (Top Priority) | Tourism sector companies | Soft |

| Sensitize the tourism sector to the efficient management of resources. | Level 2 (High Priority) | Tourism sector companies | Soft |

| Requiring tour operators to provide less pollutant mobility and passenger transport solutions. | Level 2 (High Priority) | Tourism sector companies | Regulatory |

| Increase the emphasis on climate change within mandatory training and education programs for higher technicians. | Level 2 (High Priority) | Tourism sector companies | Regulatory |

| Promote the use of soft modes during the visit (e.g., bicycle use). | Level 2 (High Priority) | Local community | Soft |

| Reduce car use. | Level 2 (High Priority) | Local community | Soft |

| Sensitize tourists to more sustainable tourist practices. | Level 2 (High Priority) | Local community | Soft |

| Sectoral Groups | Needs | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Public administration |

|

|

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| Universities and research centers |

|

|

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| Tourism companies |

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lopes, H.S.; Remoaldo, P.; Ribeiro, V.; Martín-Vide, J. The Use of Collaborative Practices for Climate Change Adaptation in the Tourism Sector until 2040—A Case Study in the Porto Metropolitan Area (Portugal). Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5835. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12125835

Lopes HS, Remoaldo P, Ribeiro V, Martín-Vide J. The Use of Collaborative Practices for Climate Change Adaptation in the Tourism Sector until 2040—A Case Study in the Porto Metropolitan Area (Portugal). Applied Sciences. 2022; 12(12):5835. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12125835

Chicago/Turabian StyleLopes, Hélder Silva, Paula Remoaldo, Vítor Ribeiro, and Javier Martín-Vide. 2022. "The Use of Collaborative Practices for Climate Change Adaptation in the Tourism Sector until 2040—A Case Study in the Porto Metropolitan Area (Portugal)" Applied Sciences 12, no. 12: 5835. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12125835

APA StyleLopes, H. S., Remoaldo, P., Ribeiro, V., & Martín-Vide, J. (2022). The Use of Collaborative Practices for Climate Change Adaptation in the Tourism Sector until 2040—A Case Study in the Porto Metropolitan Area (Portugal). Applied Sciences, 12(12), 5835. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12125835