Autonomous Vehicles: An Analysis Both on Their Distinctiveness and the Potential Impact on Urban Transport Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. State of Art: An Overview on Safety for AVs (Risks, Drawbacks, and Benefits)

4. AVs Critical Issues: Aspects Related to Specific Infrastructures Components

4.1. Autonomous Vehicles Detection Capability at Intersection and for Horizontal Road Markings

4.2. AVs Effects on Roadway Pavement

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arvin, R.; Khattak, A.J.; Kamrani, M.; Rio-Torres, J. Safety evaluation of connected and automated vehicles in mixed traffic with conventional vehicles at intersections. J. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 25, 170–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burghardt, T.E.; Mosböck, H.; Pashkevich, A.; Fiolić, M. Horizontal road markings for human and machine vision. Transp. Res. Procedia 2019, 48, 3622–3633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trubia, S.; Severino, A.; Curto, S.; Arena, F.; Pau, G. Smart Roads: An Overview of What Future Mobility Will Look Like. Infrastructures 2020, 5, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagloee, S.A.; Tavana, M.; Asadi, M.; Oliver, T. Autonomous vehicles: Challenges, opportunities, and future implications for transportation policies. J. Mod. Transp. 2016, 24, 284–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanna, A.; Crispino, M.; Giustozzi, F.; Toraldo, E. Deterioration trends of asphalt pavement friction and roughness from medium-term surveys on major Italian roads. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2017, 10, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świderski, A.; Jóżwiak, A.; Jachimowski, R. Operational quality measures of vehicles applied for the transport services evaluation using artificial neural networks. Ekspolatacja Niezawodn. Maint. Reliab. 2018, 20, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trubia, S.; Severino, A.; Curto, S.; Arena, F.; Pau, G. On BRT Spread around the World: Analysis of Some Particular Cities. Infrastructures 2020, 5, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, F.; Ratti, C. The Impact of Autonomous Vehicles on Cities: A Review. J. Urban Technol. 2018, 25, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bösch, P.M.; Becker, F.; Becker, H.; Axhausen, K.W. Cost-based analysis of autonomous mobility services. Transp. Policy 2017, 64, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favarò, F.M.; Nader, N.; Eurich, S.O.; Tripp, M.; Varadaraju, N. Examining accident reports involving autonomous vehicles in California. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasiguano, C.; Danny, Z.; Alex, T.; Camacho, O.; Alvaro, P.; Ananganó Alvarado, G. A review of autonomous vehicle technology and its use for the COVID-19 contingency. In Artículo de Investigación. Revista Ciencia e Ingeniería; Universidad de los Andes (ULA): Merida, Venezuela, 2021; Volume 42, pp. 43–52, ISSN 1316-7081; ISSN Elect. 2244-8780. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Liao, Q.H.; Gan, L.; Ma, F.; Cheng, J.; Xie, X.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, S.; et al. The Role of the Hercules Autonomous Vehicle during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Autonomous Logistic Vehicle for Contactless Goods Transportation. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2021, 28, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Taeihagh, A.; De Jong, M. The Governance of Risks in Ridesharing: A Revelatory Case from Singapore. Energies 2018, 11, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taeihagh, A.; Lim, H.S.M. Governing autonomous vehicles: Emerging responses for safety, liability, privacy, cybersecurity, and industry risks. Transp. Rev. 2018, 39, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Wong, Y.D.; Liu, X.; Rau, A. Exploration of an integrated automated public transportation system. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 8, 100275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, K.; Peters, S.; van Wee, B. Transportation technologies, sharing economy, and teleactivities: Implications for built environmentand travel. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 92, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceder, A. Urban mobility and public transport: Future perspectives and review. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2020, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccardo Mariani, R. An Overview of Autonomous Vehicles Safety. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Reliability Physics Symposium (IRPS), Burlingame, CA, USA, 11–15 March 2018; pp. 6A.1-1–6A.1-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trubia, S.; Curto, S.; Barberi, S.; Severino, A.; Arena, F.; Pau, G. Analysis and Evaluation of Ramp Metering: From Historical Evolution to the Application of New Algorithms and Engineering Principles. Sustainability 2021, 13, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjun, P. Comparative Study of Artificial Intelligence Algorithms for Autonomous Vehicle. Int. J. Sci. Res. (IJSR) 2020, 9, 1579–1584. Available online: https://www.ijsr.net/search_index_results_paperid.php?id=ART20204360 (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- Khan, S.K.; Shiwakoti, N.; Stasinopoulos, P.; Chen, Y. Cyber-attacks in the next-generation cars, mitigation techniques, anticipated readiness and future directions. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2020, 148, 105837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.; Islam, M.; Khan, Z. ‘Security of Connected and Automated Vehicles’, The Bridge. Natl. Acad. Eng. 2019, 49, 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Dadashzadeh, N.; Ergun, M. An Integrated Variable Speed Limit and ALINEA Ramp Metering Model in the Presence of High Bus Volume. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Xu, H.; Liu, H.; Wu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, D. Detection and tracking of pedestrians and vehicles using roadside LiDAR sensors. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 100, 68–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.M.; Nam, S.H.; Park, K.R. Enhanced Detection and Recognition of Road Markings Based on Adaptive Region of Interest and Deep Learning. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 109817–109832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Z.; Zhang, Q. Semi-automatic road lane marking detection based on point-cloud data for mapping. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, L.A.; Le, M.H. Robust U-Net-based Road Lane Markings Detection for Autonomous Driving. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on System Science and Engineering (ICSSE), Dong Hoi, Vietnam, 20–21 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, P.; Islam, M.A. Movement of Autonomous Vehicles in Work Zone Using New Pavement Marking: A New Approach. J. Transp. Technol. 2020, 10, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.; Rubenecia, A.; Choi, H.H. Reservation-Based Intersection Crossing Scheme for Autonomous Vehicles Traveling in a Speed Range. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Information Networking (ICOIN), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 9–11 January 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chuprov, S.; Viksnin, I.; Kim, I.; Nedosekin, G. Optimization of Autonomous Vehicles Movement in Urban Intersection Management System. In Proceedings of the 24th Conference of Open Innovations Association (FRUCT), Moscow, Russia, 8–12 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

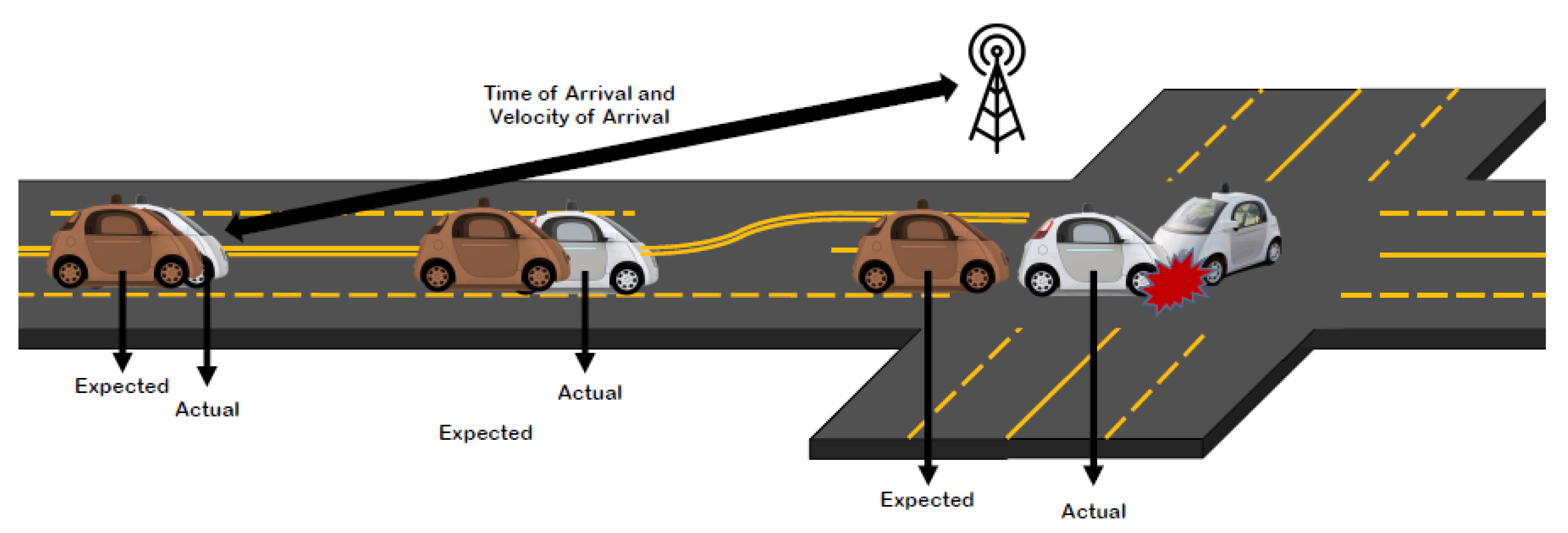

- Dedinsky, R.; Khayatian, M.; Mehrabian, M.; Shrivastava, A. A Dependable Detection Mechanism for Intersection Management of Connected 2 Autonomous Vehicles Aviral Shrivastava. In Workshop on Autonomous Systems Design (ASD 2019); Schloss Dagstuhl-Leibniz-Zentrum fuer Informatik: Wadern, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

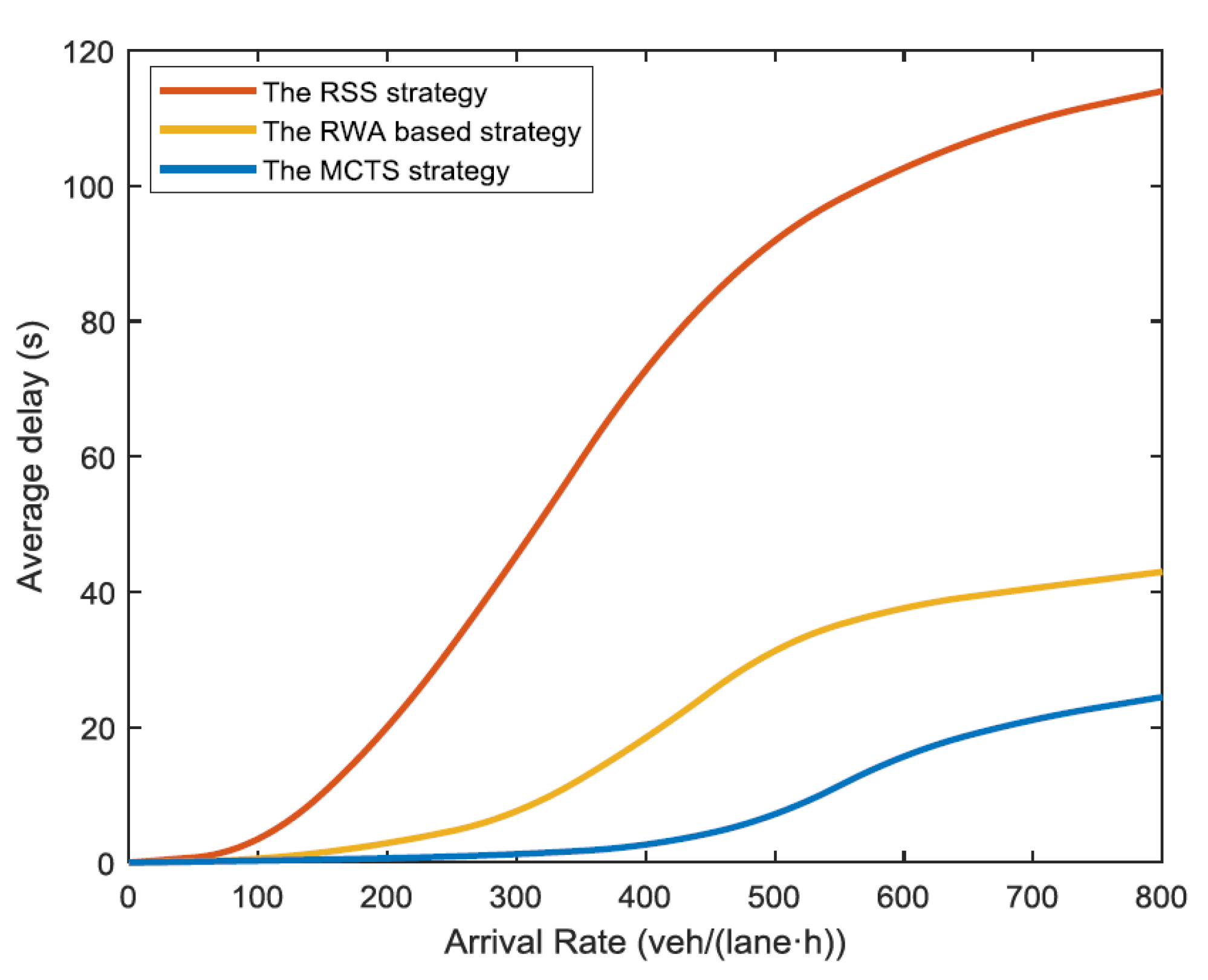

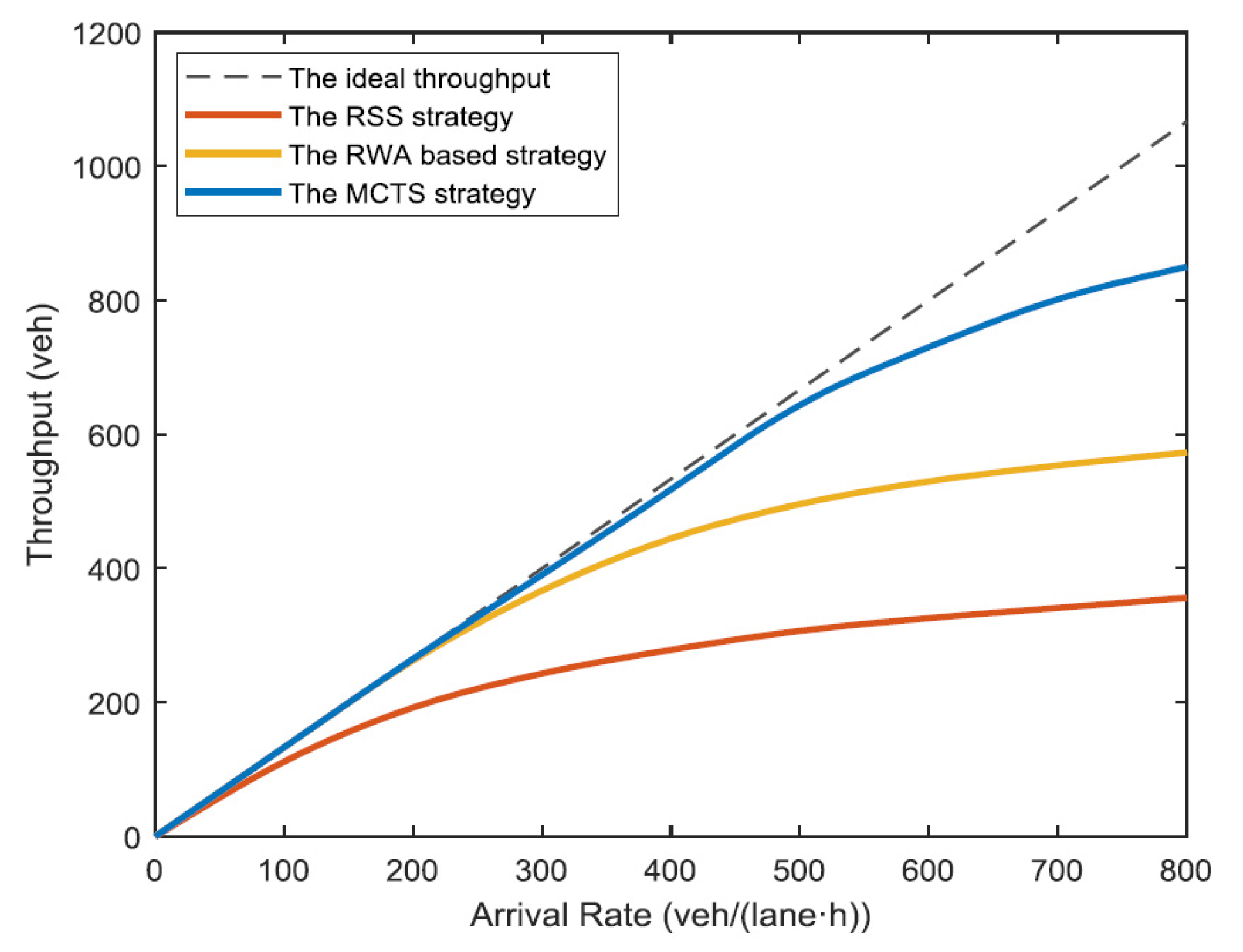

- Xing, Y.; Zhao, C.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, F.Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Su, Y.; Cao, D. A Right-of-Way Based Strategy to Implement Safe and Efficient Driving at Non-Signalized Intersections for Automated Vehicles. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.01150. [Google Scholar]

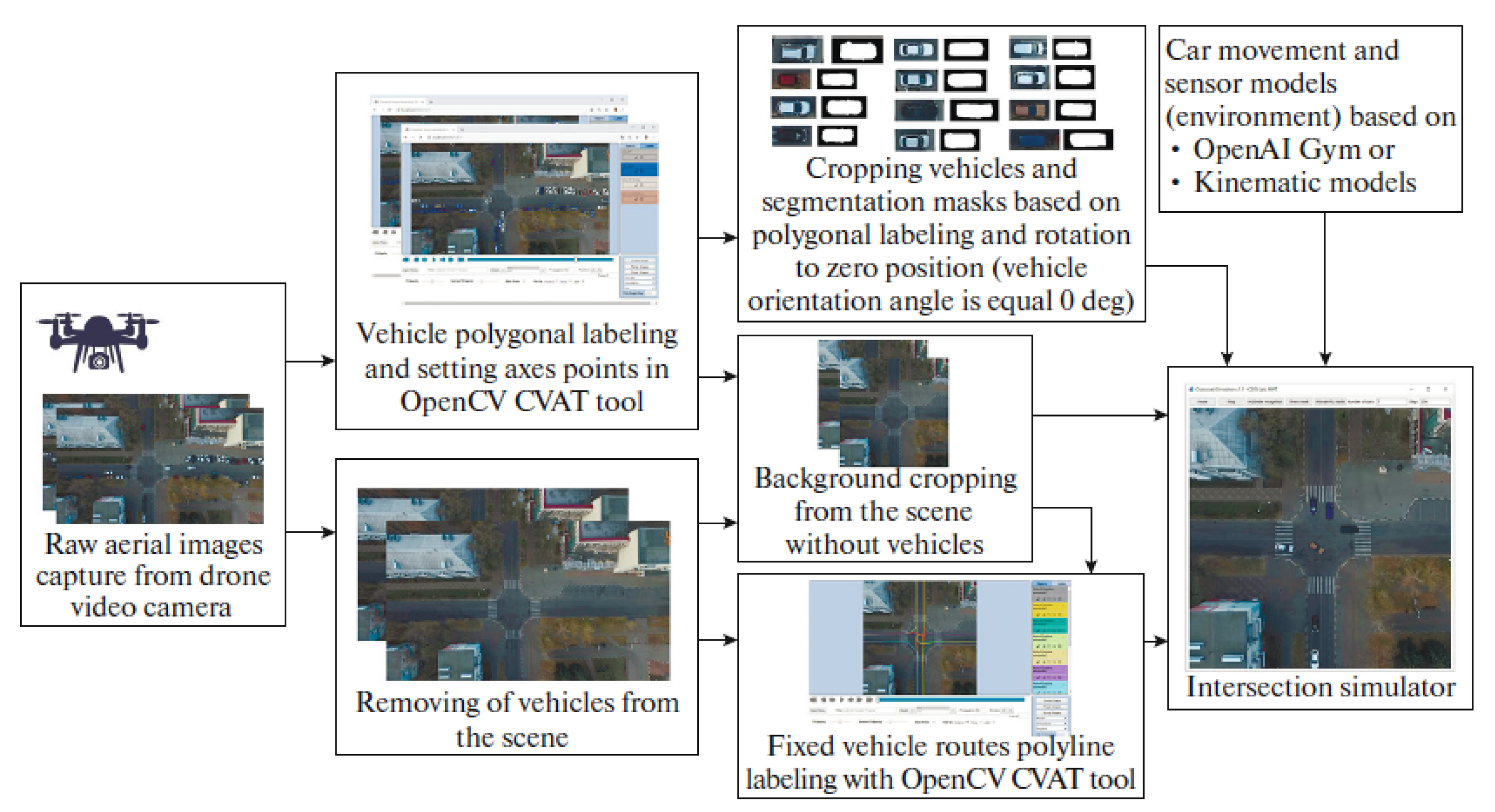

- Yudin, D.A.; Skrynnik, A.; Krishtopik, A.; Belkin, I.; Panov, A.I. Object Detection with Deep Neural Networks for Reinforcement Learning in the Task of Autonomous Vehicles Path Planning at the Intersection. Opt. Mem. Neural Netw. 2019, 28, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isele, D.; Rahimi, R.; Cosgun, A.; Subramanian, K.; Fujimura, K. Navigating Occluded Intersections with Autonomous Vehicles using Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 21–25 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, A.; Shafiee, M.J.; Siva, P.; Wang, X.Y. A Deep-Structured Fully Connected Random Field Model for Structured Inference. IEEE Access 2015, 3, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olayode, O.I.; Tartibu, L.K.; Okwu, M.O. Application of Artificial Intelligence in Traffic Control System of Non-autonomous Vehicles at Signalized Road Intersection. Procedia CIRP 2020, 91, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

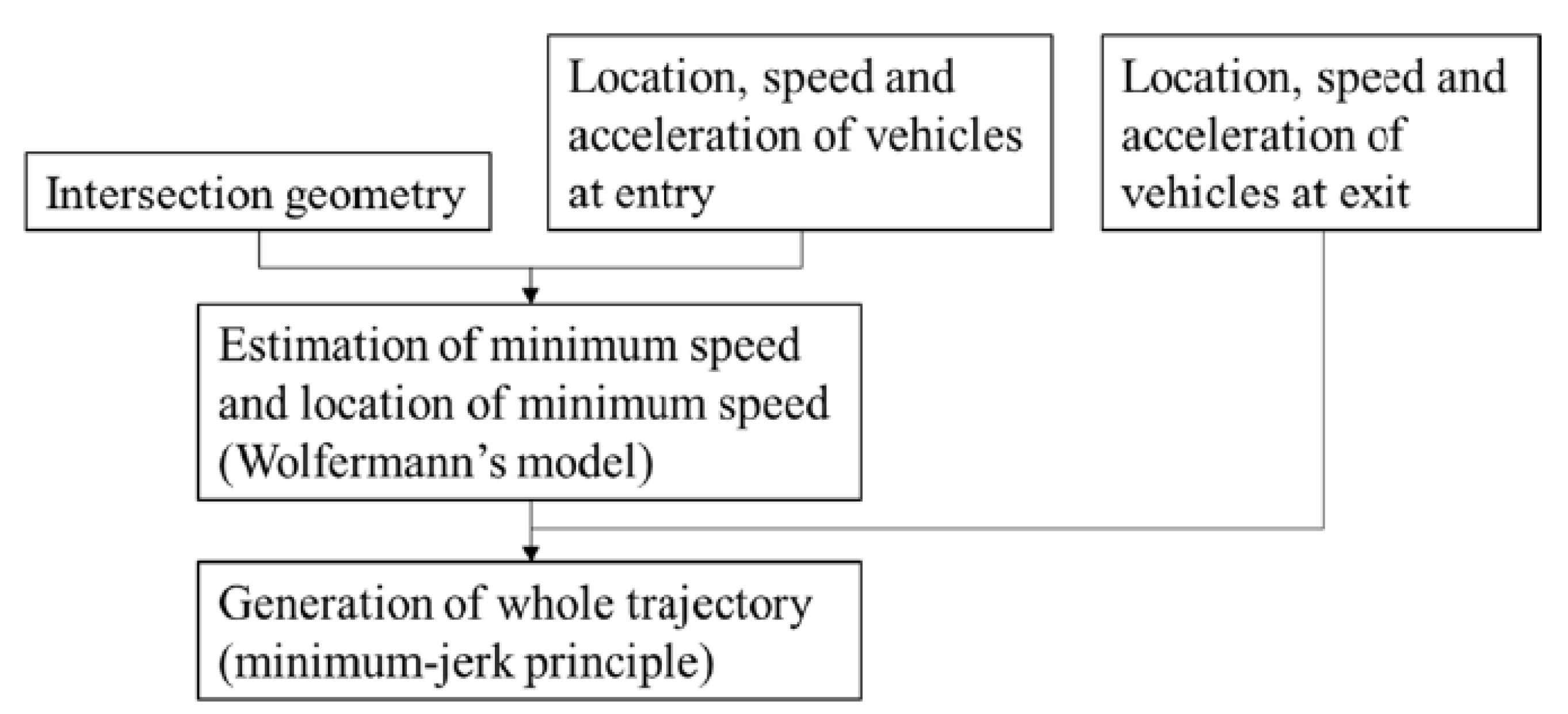

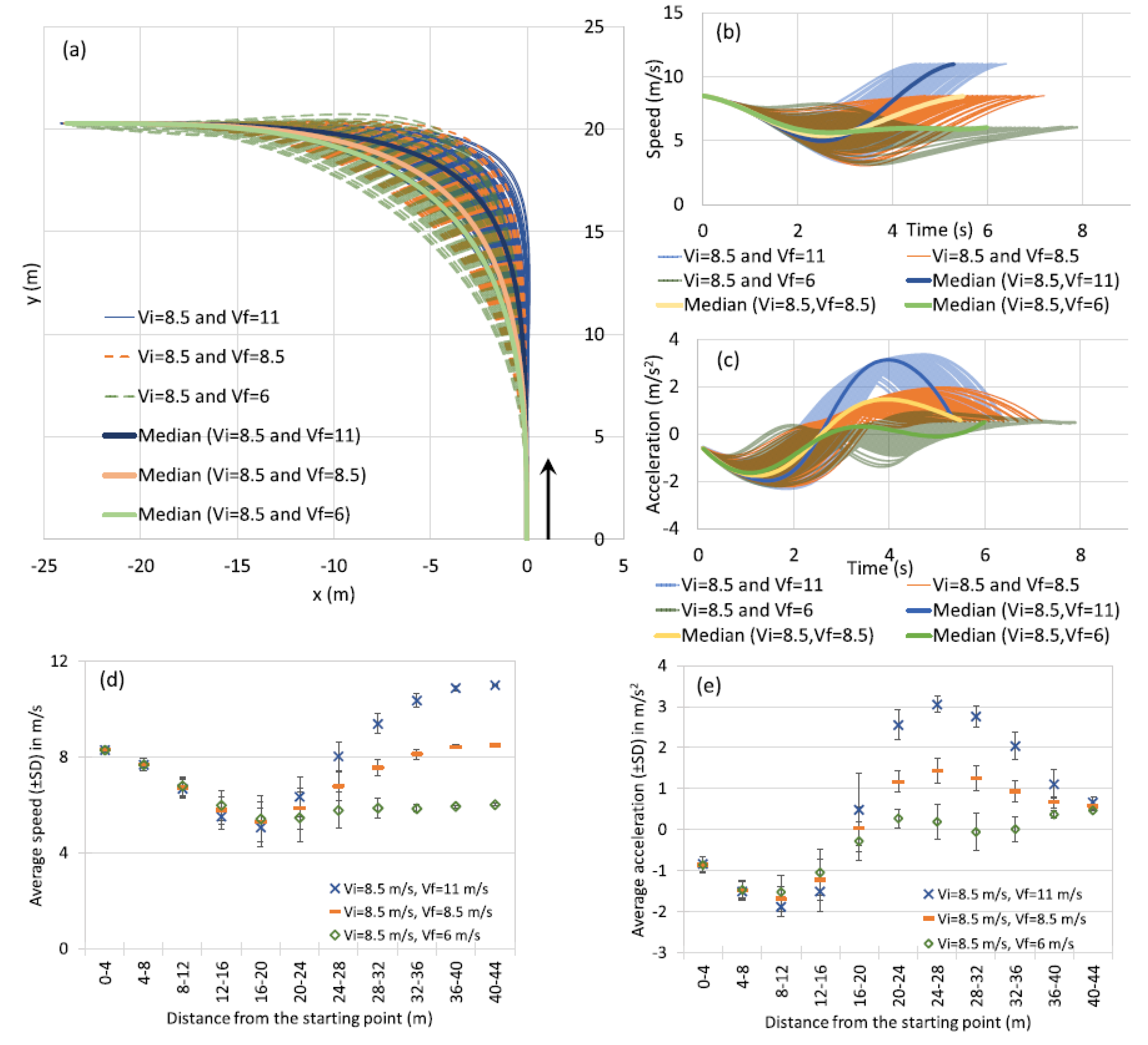

- Dias, C.; Iryo-Asano, M.; Abdullah, M.; Oguchi, T.; Alhajyaseen, W. Modeling Trajectories and Trajectory Variation of Turning Vehicles at Signalized Intersections. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 109821–109834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfermann, A.; Alhajyaseen, W.K.; Nakamura, H. Modeling speed pro_les of turning vehicles at signalized intersections. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Road Safety and Simulation RSS2011, Indianapolis, IN, USA, 14–16 September 2011; Transportation Research Board TRB, 01/01/2011. pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Flash, T.; Hogan, N. The coordination of arm movements: An experimentally confirmed mathematical model. J. Neurosci. 1985, 5, 1688–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berktaş, E. Şentürk; Tanyel, S. Effect of Autonomous Vehicles on Performance of Signalized Intersections. J. Transp. Eng. Part A Syst. 2020, 146, 04019061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, M.W.; Rey, D. Conflict-point formulation of intersection control for autonomous vehicles. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2017, 85, 528–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

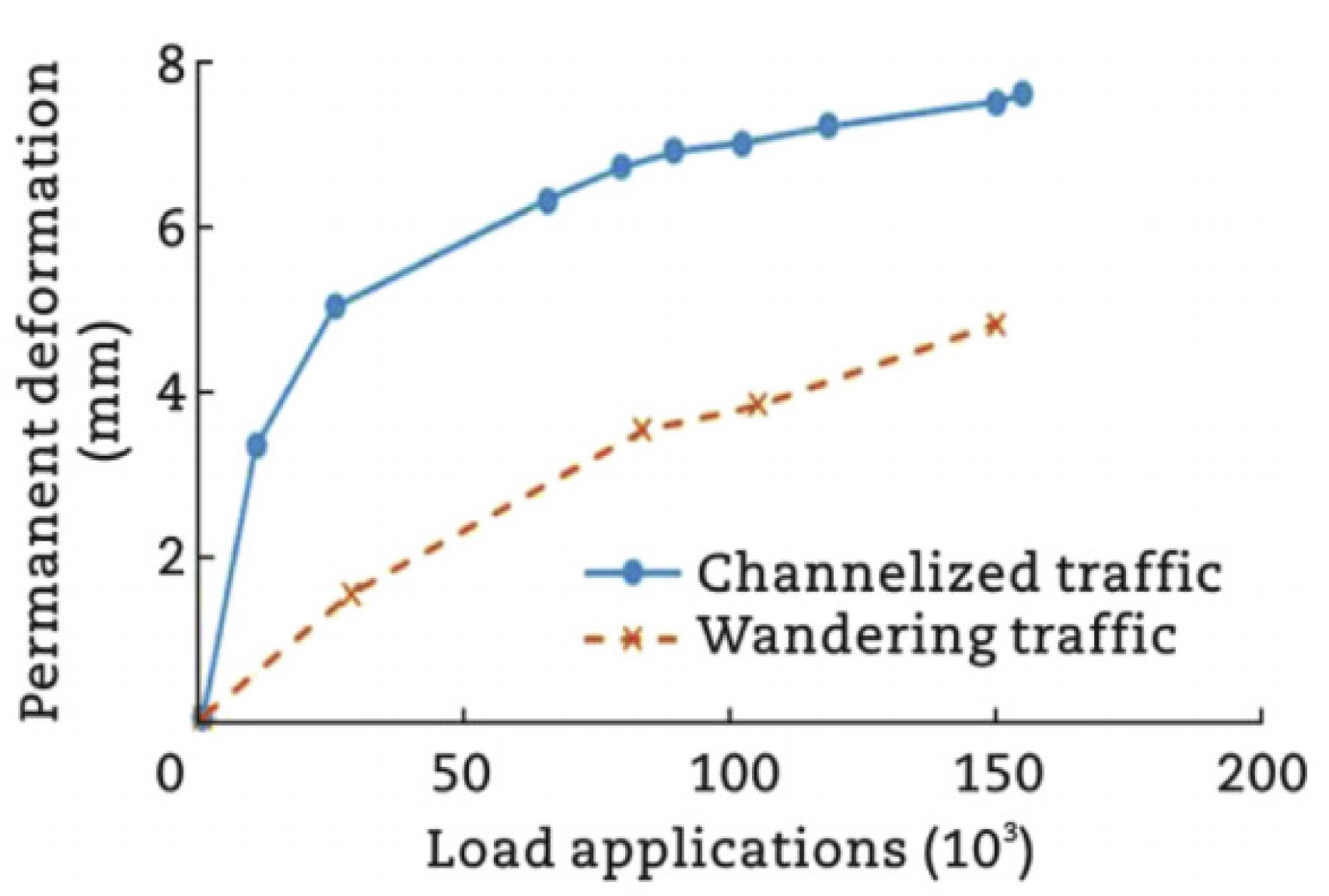

- Chen, F.; Song, M.; Ma, X.; Zhu, X. Assess the impacts of different autonomous trucks’ lateral control modes on asphalt pavement performance. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 103, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gołębiowski, P.; Gołda, I.J.; Izdebski, M.; Kłodawski, M.; Jachimowski, R.; Szczepański, E. The evaluation of the sustainable transport system development with the scenario analyses procedure. J. Vibroeng. 2017, 19, 5627–5638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gungor, O.E.; Al-Qadi, I.L. Wander 2D: A flexible pavement design framework for autonomous and connected trucks. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacyna, M.; Wasiak, M.; Kłodawski, M.; Lewczuk, K. Simulation model of transport system of poland as a tool for developing sustainable transport. Arch. Transp. 2014, 31, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyn, W.J.V.; Maina, J.W. Guidelines for the use of accelerated pavement testing data in autonomous vehicle infrastructure research. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. (Engl. Ed.) 2019, 6, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesoriere, G.; Canale, A.; Severino, A.; Mrak, I.; Campisi, T. The management of pedestrian emergency through dynamic assignment: Some consideration about the “Refugee Hellenism” Square of Kalamaria (Greece). AIP Conf. Proc. 2019, 2186, 160004. [Google Scholar]

- Arena, F.; Pau, G.; Severino, A. An Overview on the Current Status and Future Perspectives of Smart Cars. Infrastructures 2020, 5, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strategy | Description |

|---|---|

| No-Response | No specific actions or dedicated regulations are implemented. An example might be the lack of dedicated national policies to manage AVs acceptance standards, traffic operations, and related consequences. Although this might seem the cheaper option, at first glance, AV-related risks left alone without management can be higher in the end, leading potentially to significant costs arising from the lack of risk management and making it not economically convenient in the long term. |

| Prevention-oriented | Risk is managed by avoidance, i.e., risk is reduced by removing the hazard, trying to prevent negative consequences by eliminating the source that would cause them. An example is the prohibition of AVs for certain times or areas of the road network. |

| Control-oriented | The hazard is here admitted and controlled by making predictions and regulations as an attempt to reduce the probability that consequences would happen. Examples of regulations could involve the mandatory requirements for AVs certified safety standards, dedicated road traffic policies, use of traffic prediction models, and so on. |

| Toleration-oriented | With this approach, governments tend to make sure to be in a strong and solid position when facing risks across diverse situations. An example is the publication of comprehensive lists to describe contingency plans or clarify insurance liabilities while seeking alternative solutions to mitigate risks. |

| Adaptation-oriented | Being an adaptation strategy, the approach consists of improving the reaction caused by an existing source, accepting the hazard and its uncertainties, reducing the impact of consequences, and improving system performances. The aim is to achieve a resilient system. |

| Scenarios | Los | Vehs | Fuel Consumption | Co | Nox | Voc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No-Control | LOS F | 5509.00 | 3770 | 69,613 | 13,544 | 16,133 |

| ALINEA | LOS D | 5759.00 | 2319 | 42,822 | 8332 | 9925 |

| VSL | LOS D | 5692.00 | 2140 | 39,511 | 7687 | 9157 |

| VSL+ALINEA | LOS D | 5741.00 | 1902 | 35,114 | 6832 | 8138 |

| VSL+ALINEA/B | LOS C | 5904.20 | 415 | 29,024 | 5647 | 6726 |

| Marking Type | Pavement Marking |

|---|---|

| Lane Open |  |

| Lane Closed | |

| Right Turn Single Lane Ramp Closure | |

| Right Turn For Single Lane Right Ramp Closure | |

| Merge Right | |

| Left Turn Two-Lane Ramp-Left Lane Closure | |

| Left Turn Two-Lane Ramp-Right Lane Closure | |

| Left Turn Single Lane Ramp Closure | |

| U-Turn | |

| Start Work Zone | |

| End Work Zone | |

| Work Zone Edge Line (Contrast Pavement Marking) |

| Effect | Consequence |

|---|---|

| Channelized traffic flow | Easier forecasting process related to cracking and deformation detection. |

| Speed load frequency | Pavement surface optimization due to higher frequency of load application. |

| Acceleration/deceleration optimization | Reduction of longitudinal pavement surface stress. |

| Stop/start maneuvers reduction at intersection | Incidents reduction, traffic management facilitations. |

| Traffic increase at night | Increased pavement life-cycle due to lower temperature. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Severino, A.; Curto, S.; Barberi, S.; Arena, F.; Pau, G. Autonomous Vehicles: An Analysis Both on Their Distinctiveness and the Potential Impact on Urban Transport Systems. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3604. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11083604

Severino A, Curto S, Barberi S, Arena F, Pau G. Autonomous Vehicles: An Analysis Both on Their Distinctiveness and the Potential Impact on Urban Transport Systems. Applied Sciences. 2021; 11(8):3604. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11083604

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeverino, Alessandro, Salvatore Curto, Salvatore Barberi, Fabio Arena, and Giovanni Pau. 2021. "Autonomous Vehicles: An Analysis Both on Their Distinctiveness and the Potential Impact on Urban Transport Systems" Applied Sciences 11, no. 8: 3604. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11083604

APA StyleSeverino, A., Curto, S., Barberi, S., Arena, F., & Pau, G. (2021). Autonomous Vehicles: An Analysis Both on Their Distinctiveness and the Potential Impact on Urban Transport Systems. Applied Sciences, 11(8), 3604. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11083604