The Effect of Whole-Body Vibration Training on Biomarkers and Health Beliefs of Prefrail Older Adults

Abstract

1. Background

Aims

- To compare the homogeneity of the demographic characteristics, biomarkers, and health beliefs of experimental and control groups in pre-test.

- To investigate differences pre- and post- test in whole-body vibration training and control training regarding their effects on biomarkers and health beliefs, for prefrail community dwelling older persons.

- To investigate differences between experimental (whole-body vibration) group and control group regarding their effects on biomarkers and health beliefs.

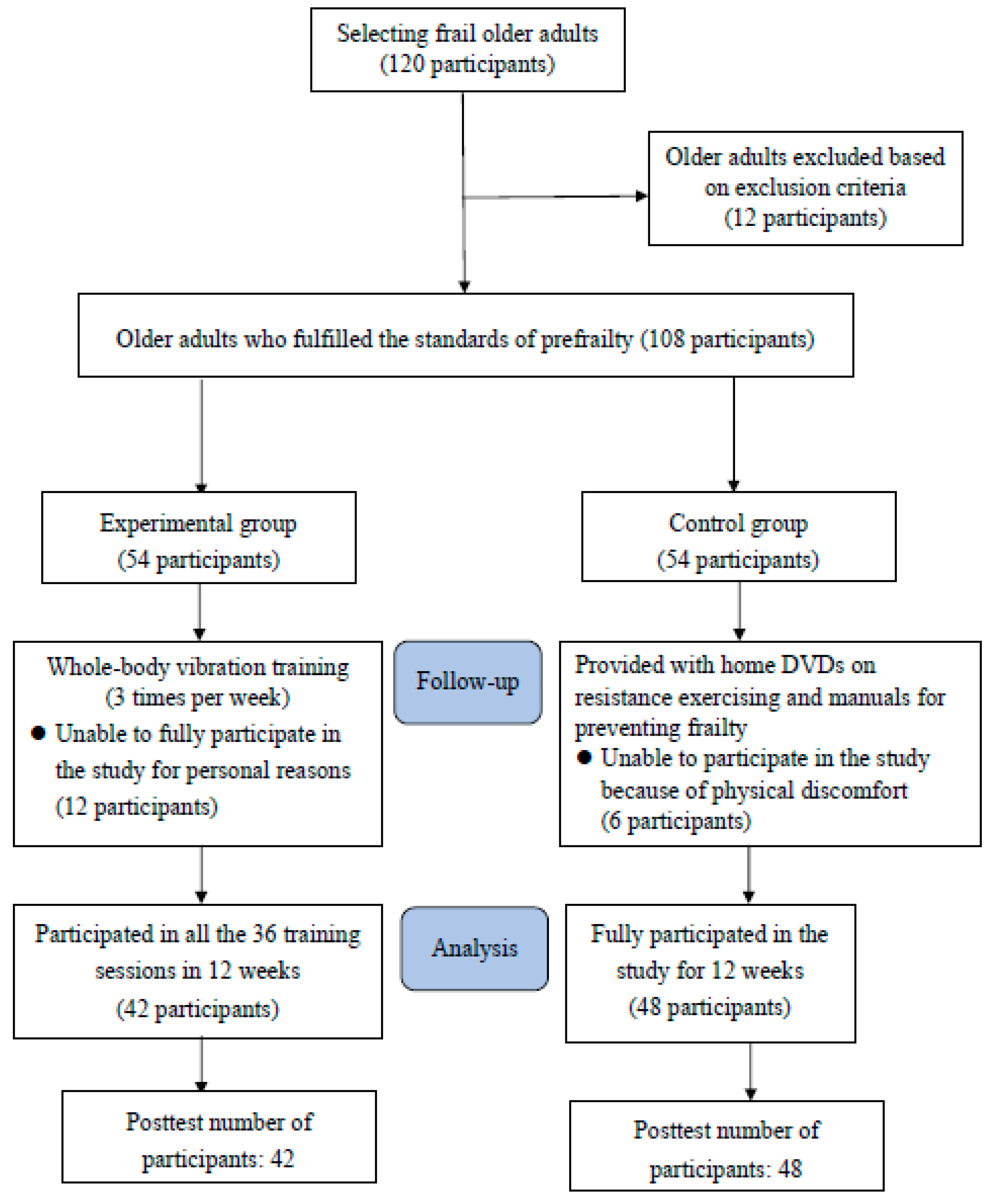

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Sample Size

2.4. Research Assessment

2.4.1. Prefrailty Assessment

2.4.2. Demographic Status

2.4.3. Biomarkers

2.5. Whole-Body Vibration Training

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Homogeneity of the Demographic Characteristics, Biomarkers, and Health Beliefs between Experimental and Control Groups in Pretest

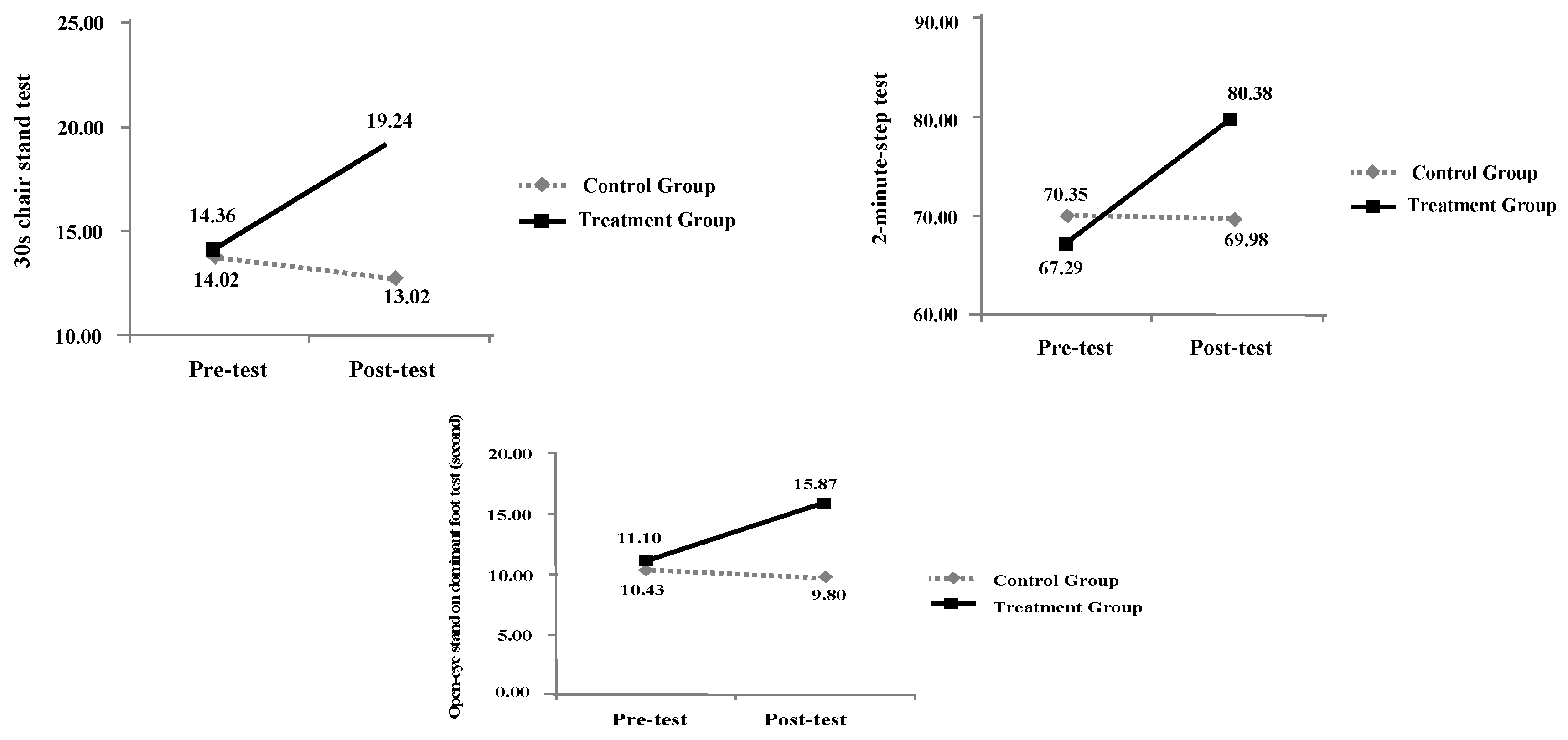

3.2. The Primary Outcome of Pre-Test and Post-Test Results of the Experimental and Control Groups for Biomarkers and Health Beliefs

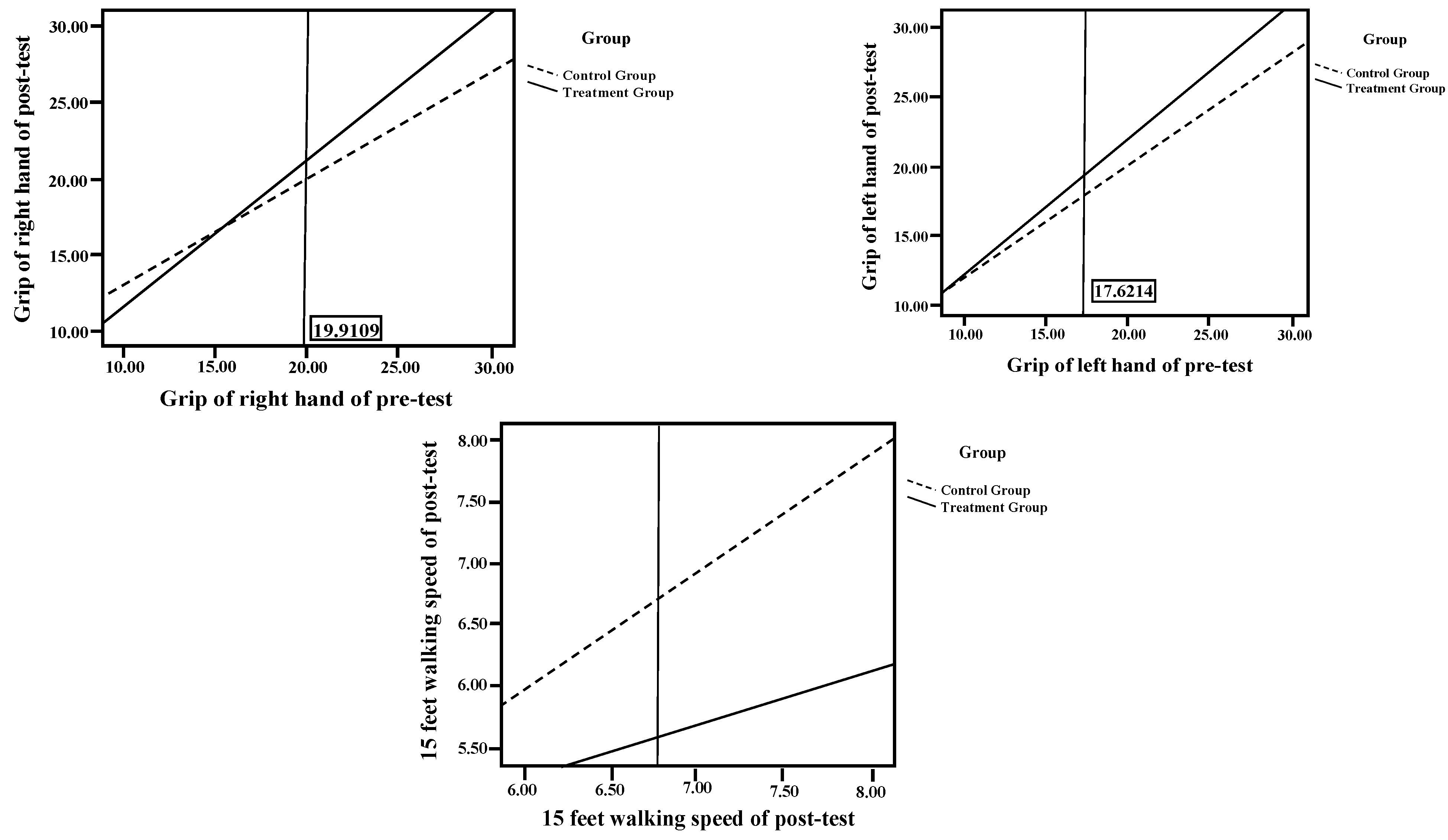

3.3. Effects of Whole-Body Vibration Training between Two Groups on Biomarkers

3.4. Effects of Whole-Body Vibration Training on Health Beliefs

4. Discussion

4.1. Primary Outcome of Pretest and Posttest Results of the Experimental and Control Groups for Biomarkers and Health Beliefs

4.2. Posttest ANCOVA of the Experimental and Control Groups for Biomarkers and Health Beliefs

5. Conclusions

6. Implications for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO (The World Health Organization). Report of the World Health Organization. Active ageing: A policy framework. Aging Male 2002, 5, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Executive Yuan, ROC. Annual Census Report in Taiwan Area 2019; Ministry of Internal Affairs, The Executive Yuan, ROC: Taipei City, Taiwan, 2019. Available online: https://www.moi.gov.tw/stat/news_detail.aspx?sn=13742 (accessed on 19 July 2019).

- Bloom, D.; Canning, D.; Lubet, A. Global population aging: Facts, challenges, solutions & perspectives. Daedalus 2015, 144, 80–92. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, S. Economic and social implications of aging societies. Science 2014, 346, 587–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Lin, P.; Yang, R.; Yang, R. The preliminary effect of whole-body vibration intervention on improving the skeletal muscle mass index, physical fitness, and quality of life among older people with sarcopenia. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fried, L.P.; Tangen, C.M.; Walston, J.; Newman, A.B.; Hirsch, C.; Gottdiener, J.; Seeman, T.; Tracy, R.; Kop, W.J.; Burke, G.; et al. Frailty in older adults evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, M146–M156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-Flores, E.; Romero-Morales, C.; Becerro de Bengoa-Vallejo, R.; Rodríguez-Sanz, D.; Palomo-López, P.; López-López, D.; Calvo-Lobo, C. Sex Differences in Frail Older Adults with Foot Pain in a Spanish Population: An Observational Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.F.; Lin, P.L. Frail phenotype and mortality prediction: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 1362–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Flores, E.; de Bengoa Vallejo, R.B.; Losa-Iglesias, M.E.; Palomo-López, P.; Calvo-Lobo, C.; López-López, D.; Romero-Morales, C. The reliability, validity, and sensitivity of the Edmonton Frail Scale (EFS) in older adults with foot disorders. Aging 2020, 12, 24623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensrud, K.E.; Ewing, S.K.; Taylor, B.C.; Fink, H.A.; Cawthon, P.M.; Stone, K.L.; Hillier, T.A.; Cauley, J.A.; Hochberg, M.C.; Rodondi, N.; et al. Comparison of 2 frailty indexes for prediction of falls, disability, fractures, and death in older women. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008, 168, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, J.E.; Malmstrom, T.K.; Miller, D.K. A simple frailty questionnaire (FRAIL) predicts outcomes in middle aged African Americans. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2012, 16, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Weng, C.S.; Liu, L.M.; Jiao, W.G.; Zhu, C.X. Test-retest reliability of grip strength assessment in bed-ridden Senile patients. Chin. J. Rehabil. Theory Pract. 2009, 15, 259–260. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Academic press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Guralnik, J.; Winograd, C. Physical performance measures in the assessment of older persons. Aging 1994, 6, 303–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Park, I.; Joo Lee, H.; Lee, O. The reliability and validity of gait speed with different walking pace and distances against general health, physical function, and chronic disease in aged adults. J. Exerc. Nutr. Biochem. 2016, 20, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, B.; Marin, R.; Cyhan, T.; Roberts, H.; Gill, N. Normative values for the unipedal stance test with eyes open and closed. J. Geriatr. Phys. Ther. 2007, 30, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazaheri, M.; Salavati, M.; Negahban, H.; Parnianpour, M. Test-retest reliability of postural stability measures during quiet standing in patients with a history of nonspecific low back pain. Biomed. Eng. 2010, 22, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikli, R.E.; Jones, C.J. Development and validation of criterion-referenced clinically relevant fitness standards for maintaining physical independence in later years. Gerontologist 2013, 53, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.F.; Yang, R.S.; Lin, T.C.; Chiu, S.C.; Chen, M.L.; Lee, H.C. The discrimination of using the short physical performance battery to screen frailty for community-dwelling elderly people. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2014, 46, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marín, F.; González-Macías, J.; Díez-Pérez, A.; Palma, S.; Delgado-Rodríguez, M. Relationship between bone quantitative ultrasound and fractures: A meta-analysis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2006, 21, 1126–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.Y.; Gershon, A.S.; Ko, D.T.; Thilen, S.R.; Yun, L.; Beattie, W.S.; Wijeysundera, D.N. Trends in pulmonary function testing before noncardiothoracic surgery. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015, 175, 1410–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chen, K.W.; Chang, S.F.; Lin, P.L. Frailty as a predictor of future fracture in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2017, 14, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Lin, H.; Cheng, C. The relationship of frailty and hospitalization among older people: Evidence from a meta-analysis. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2018, 50, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, N.; Pang, M.; Ng, S.; Ng, G. Optimal frequency/time combination of whole body vibration training for developing physical performance of people with sarcopenia: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2017, 31, 1313–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, P.O.; Neyman, J. Tests of certain linear hypotheses and their application to some educational problems. Stat. Res. Mem. 1936, 1, 57–93. [Google Scholar]

- Furness, T.P.; Maschette, W.E. Influence of whole body vibration platform frequency on neuromuscular performance of community-dwelling older adults. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2009, 23, 1508–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees, S.S.; Murphy, A.J.; Watsford, M.L. Effects of whole body vibration on postural steadiness in an older population. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2009, 12, 440–444. [Google Scholar]

- Bemben, D.; Stark, C.; Taiar, R.; Bernardo-Filho, M. Relevance of whole-body vibration exercises on muscle strength/power and bone of elderly individuals. Dose-Response 2018, 16, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepherd, A.I.; Gilchrist, M.; Winyard, P.G.; Jones, A.M.; Hallmann, E.; Kazimierczak, R.; Rembialkowska, E.; Benjamin, N.; Shore, A.C.; Wilkerson, D.P. Effects of dietary nitrate supplementation on the oxygen cost of exercise and walking performance in individuals with type 2 diabetes: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 86, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrie, K.J.; Rief, W. Psychobiological mechanisms of control and nocebo effects: Pathways to improve treatments and reduce side effects. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 2019, 70, 599–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Experimental Group (n = 42) | Control Group (n = 48) | Number | x2 | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Sex | 5.143 | 0.023 * | ||||||

| Male | 3 | 7.1 | 12 | 25 | 15 | 16.7 | ||

| Female | 39 | 92.9 | 36 | 75 | 75 | 83.3 | ||

| Age | 0.34 | 0.854 | ||||||

| 65–74 | 29 | 69 | 34 | 70.8 | 63 | 70 | ||

| 75 above | 13 | 31 | 14 | 29.2 | 27 | 30 | ||

| Education level | 2.64 | 0.45 | ||||||

| Illiterate | 10 | 23.8 | 15 | 31.3 | 25 | 27.8 | ||

| Primary school | 24 | 57.1 | 20 | 41.7 | 44 | 48.9 | ||

| Elementary school | 5 | 11.9 | 10 | 20.8 | 15 | 16.7 | ||

| High school | 3 | 7.1 | 3 | 6.3 | 6 | 6.7 | ||

| Living arrangements | 0.62 | 0.804 | ||||||

| Living alone | 6 | 14.3 | 6 | 12.5 | 12 | 13.3 | ||

| Living with their families | 36 | 85.7 | 42 | 87.5 | 78 | 86.7 | ||

| Number of chronic diseases | 2.82 | 0.245 | ||||||

| No diseases | 4 | 9.5 | 8 | 16.7 | 12 | 13.3 | ||

| One diseases | 17 | 40.5 | 24 | 50 | 41 | 45.6 | ||

| Two diseases | 21 | 50 | 16 | 33.3 | 37 | 41.1 | ||

| Hospitalization history in the last year | 0.02 | 0.896 | ||||||

| No | 32 | 76.2 | 36 | 75 | 68 | 75.6 | ||

| Yes | 10 | 23.8 | 12 | 25 | 22 | 24.4 | ||

| Falling experience in the last year | 3.21 | 0.073 | ||||||

| No | 24 | 57.1 | 36 | 75 | 60 | 66.7 | ||

| Yes | 18 | 42.9 | 12 | 25 | 30 | 33.3 | ||

| Item | Groups | Number | Mean | SD | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomarkers | ||||||

| Right-hand grip strength | experimental | 42 | 21.79 | 6.03 | −1.398 | 0.166 |

| control | 48 | 21.56 | 8.29 | |||

| Left-hand grip strength | experimental | 42 | 22.04 | 6.27 | −1.528 | 0.13 |

| control | 48 | 21.92 | 7.65 | |||

| 15-foot walking speed | experimental | 42 | 7.3 | 0.66 | 1.344 | 0.182 |

| control | 48 | 7.1 | 0.73 | |||

| 30-sec chair stand | experimental | 42 | 14.35 | 2.25 | 0.61 | 0.543 |

| control | 48 | 14.02 | 2.88 | |||

| One-leg standing | experimental | 42 | 11.09 | 8 | 0.381 | 0.704 |

| control | 48 | 10.43 | 8.59 | |||

| 2-min step | experimental | 42 | 77.28 | 20.17 | −0.871 | 0.387 |

| control | 48 | 70.35 | 11.43 | |||

| Health beliefs | ||||||

| Self-perceived morbidity of frailty | experimental | 42 | 2.55 | 0.37 | 1.315 | 0.192 |

| control | 48 | 2.45 | 0.33 | |||

| Self-perceived severity of frailty | experimental | 42 | 2.28 | 0.46 | −1.087 | 0.28 |

| control | 48 | 2.19 | 0.34 | |||

| Benefits of preventing frailty | experimental | 42 | 2.66 | 0.57 | −0.553 | 0.582 |

| control | 48 | 2.72 | 0.4 | |||

| Self-perceived obstacles to frailty | experimental | 42 | 3.17 | 0.39 | −1.211 | 0.229 |

| control | 48 | 3.26 | 0.31 | |||

| Cues to action | experimental | 42 | 2.45 | 0.4 | 0.106 | 0.916 |

| control | 48 | 2.44 | 0.28 |

| Variable | Group | Pretest | Posttest (Noncalibrated) | Paired t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| Biomarkers | |||||||

| Right-hand grip strength | Control (N = 48) | 21.96 | 8.29 | 21.5 | 7.13 | 0.848 | 0.401 |

| Experimental (N = 42) | 19.8 | 6.04 | 20.81 | 6.49 | −3.36 | 0.002 * | |

| Left-hand grip strength | Control (N = 48) | 21.92 | 7.65 | 21.09 | 7.24 | 1.74 | 0.089 |

| Experimental (N = 42) | 19.65 | 6.27 | 20.56 | 6.52 | −4.79 | <0.001 ** | |

| 15-foot walking speed | Control (N = 48) | 7.10 | 0.73 | 7.06 | 0.78 | 0.93 | 0.36 |

| Experimental (N = 42) | 7.30 | 0.67 | 5.85 | 0.82 | 11.03 | <0.001 ** | |

| 30-sec chair stand | Control (N = 48) | 14.02 | 2.88 | 13.02 | 2.93 | 2.69 | 0.01 * |

| Experimental (N = 42) | 14.36 | 2.25 | 19.24 | 3.29 | −9.28 | <0.001 ** | |

| One-leg standing | Control (N = 48) | 10.43 | 8.59 | 9.80 | 7.7 | 1.99 | 0.051 |

| Experimental (N = 42) | 11.1 | 8.00 | 15.87 | 10.66 | −4.65 | <0.001 ** | |

| 2-min step | Control (N = 48) | 70.35 | 11.43 | 69.98 | 11.35 | 0.49 | 0.62 |

| Experimental (N = 42) | 67.29 | 20.18 | 80.38 | 22.32 | −5.28 | <0.001 ** | |

| Health beliefs | |||||||

| Self-perceived morbidity of frailty | Control (N = 48) | 2.45 | 0.33 | 2.65 | 0.42 | −3.73 | <0.001 ** |

| Experimental (N = 42) | 2.55 | 0.38 | 3.82 | 0.3 | −16.83 | <0.001 ** | |

| Self-perceived severity of frailty | Control (N = 48) | 2.28 | 0.34 | 2.44 | 0.31 | −3.68 | <0.001 ** |

| Experimental (N = 42) | 2.19 | 0.47 | 3.59 | 0.29 | −14.98 | <0.001 ** | |

| Benefits of preventing frailty | Control (N = 48) | 2.72 | 0.4 | 2.75 | 0.37 | −0.66 | 0.51 |

| Experimental (N = 42) | 2.66 | 0.57 | 3.96 | 0.26 | −14.39 | <0.001 ** | |

| Self-perceived obstacles to frailty | Control (N = 48) | 3.27 | 0.32 | 3.26 | 0.34 | 0.07 | 0.94 |

| Experimental (N = 42) | 3.18 | 0.39 | 2.71 | 0.43 | 7.11 | <0.001 ** | |

| Cues to action | Control (N = 48) | 2.44 | 0.28 | 2.77 | 0.37 | −5.57 | <0.001 ** |

| Experimental (N = 42) | 2.45 | 0.41 | 3.47 | 0.27 | −13.19 | <0.001 ** | |

| Source | SS | df | MS | F | p | Post Hoc Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30-sec chair stand | Group | 764.74 | 1 | 764.74 | 98.85 *** | <0.001 | Experimental > Control |

| Error | 665.32 | 86 | 7.74 | ||||

| One-leg standing | Group | 610.5 | 1 | 610.5 | 26.15 *** | <0.001 | Experimental > Control |

| Error | 2007.55 | 86 | 23.34 | ||||

| 2-min step | Group | 3356.86 | 1 | 3356.86 | 25.89 *** | <0.001 | Experimental > Control |

| Error | 11149.38 | 86 | 129.64 | ||||

| Error | 41221014 | 86 | 479314.1 | ||||

| Error | 9.97 | 86 | 0.12 | ||||

| Self-perceived obstacles to frailty | Group | 4.92 | 1 | 4.92 | 39.81 *** | <0.001 | Control > Experimental |

| Error | 10.63 | 86 | 0.12 | ||||

| Cues to action | Group | 10.21 | 1 | 10.21 | 92.96 *** | <0.001 | Experimental > Control |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chu, W.; Yang, H.-C.; Chang, S.-F. The Effect of Whole-Body Vibration Training on Biomarkers and Health Beliefs of Prefrail Older Adults. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3557. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11083557

Chu W, Yang H-C, Chang S-F. The Effect of Whole-Body Vibration Training on Biomarkers and Health Beliefs of Prefrail Older Adults. Applied Sciences. 2021; 11(8):3557. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11083557

Chicago/Turabian StyleChu, Wen, Hui-Chun Yang, and Shu-Fang Chang. 2021. "The Effect of Whole-Body Vibration Training on Biomarkers and Health Beliefs of Prefrail Older Adults" Applied Sciences 11, no. 8: 3557. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11083557

APA StyleChu, W., Yang, H.-C., & Chang, S.-F. (2021). The Effect of Whole-Body Vibration Training on Biomarkers and Health Beliefs of Prefrail Older Adults. Applied Sciences, 11(8), 3557. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11083557