Aromachology Related to Foods, Scientific Lines of Evidence: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

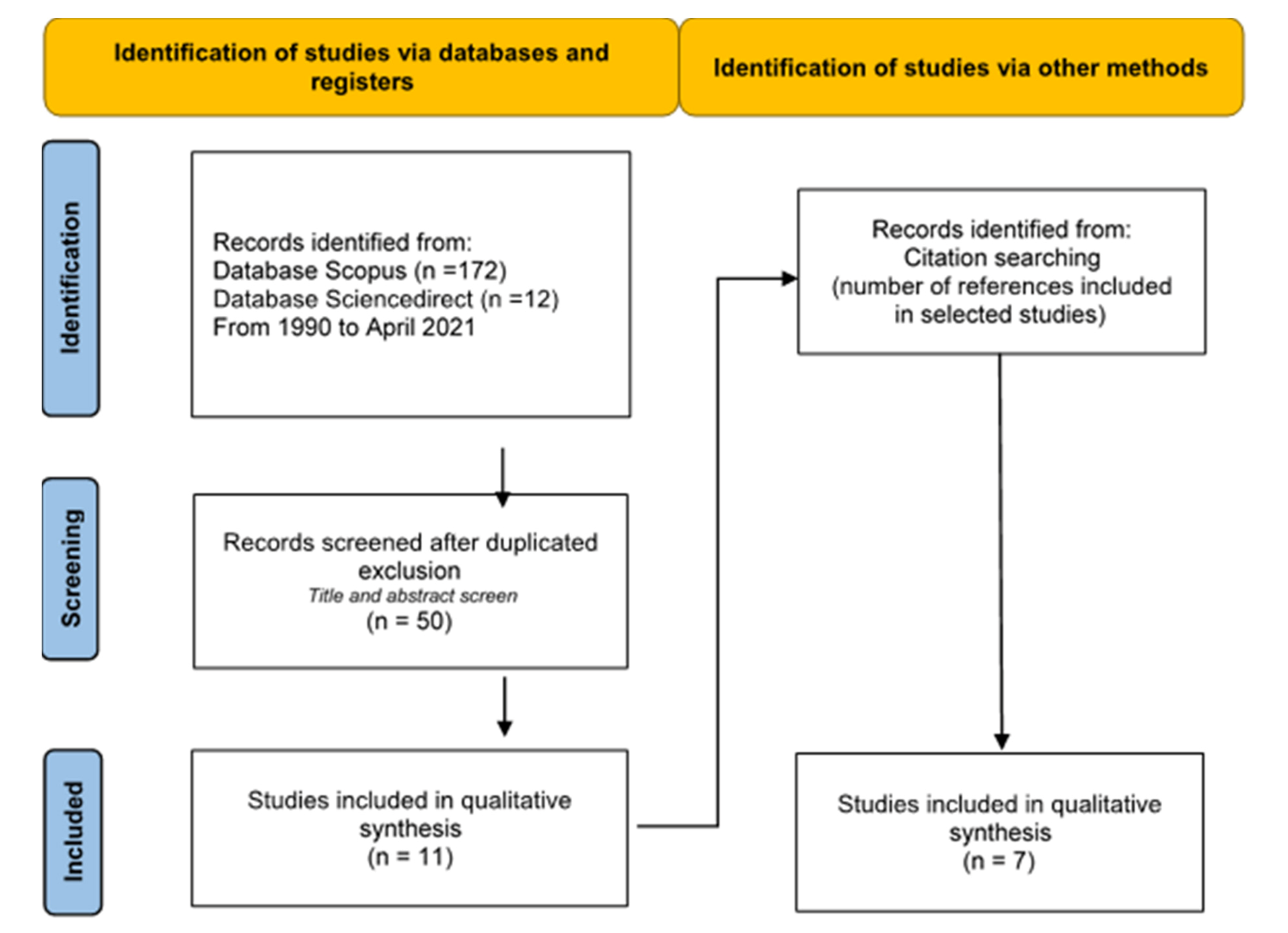

2. Literature Review Methods

2.1. Scientific Literature Review

2.2. Case Studies from Scent Company

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Revision of Scientific Literature

3.2. Case Studies

3.3. Improvements, Trends, and Future Research on Aromachology Related to Food

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lindstrom, M. Brand sense: How to build powerful brands through touch, taste, smell, sight and sound. Strateg. Dir. 2006, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluchová, J.; Berčík, J.; Horská, E. The sense of smell. In Sensory and Aroma Marketing; Sendra-Nadal, E., Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A., Eds.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2017; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Herz, R.S. Aromatherapy facts and fictions: A scientific analysis of olfactory effects on mood, physiology and behavior. Int. J. Neurosci. 2009, 119, 263–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdenzi, C.; Delplanque, S.; Barbosa, P.; Court, K.; Guinard, J.-X.; Guo, T.; Craig Roberts, S.; Schirmer, A.; Porcherot, C.; Cayeux, I.; et al. Affective semantic space of scents. Towards a universal scale to measure self-reported odor-related feelings. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 30, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, A. An integrative review of sensory marketing: Engaging the senses to affect perception, judgment and behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2012, 22, 332–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendlikova, P. Smyslový a Emoční. Master’s Thesis, University of Economics in Prague, Prague, Czechia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, M.; Weitz, A.B.; Grewal, D. Retailing Management, 8th ed.; MC Graw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2021; p. 675. [Google Scholar]

- Peck, J.; Childers, T.L. Effects of sensory factors on consumer behavior: If it tastes, smells, sounds, and feels like a duck, then it must be a... In Handbook of Consumer Psychology; Taylor & Francis Group/Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 193–219. [Google Scholar]

- Schifferstein, H.N.J.; Blok, S.T. The signal function of thematically (in)congruent ambient scents in a retail environment. Chem. Senses 2002, 27, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanlon, M. Citroen Adds a Sense of Smell to the New c4. 2 June 2005. Available online: https://newatlas.com/citroen-adds-a-sense-of-smell-to-the-new-c4/3643/ (accessed on 29 June 2021).

- Clark, P.; Esposito, M. Running Head: Management Overview of Scent as a Marketing Communications Tool; SMC Working Paper; Swiss Management Center: Hong Kong, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Butcher, D. Aromatherapy—Its past and future. Drug Cosmet. Ind. 1998, 162, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Henshaw, V.; Medway, D.; Warnaby, G.; Perkins, C. Marketing the ‘city of smells’. Mark. Theory 2016, 16, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teller, C.; Dennis, C. The effect of ambient scent on consumers’ perception, emotions and behaviour: A critical review. J. Mark. Manag. 2012, 28, 14–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verissimo, J.; Pereira, R.A. The effect of ambient scent on moviegoers’ behavior. Port. J. Manag. Stud. 2013, 18, 67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Niijima, A.; Tanida, M.; Horii, Y.; Maeda, K.; Nagai, K. Olfactory stimulation with scent of lavender oil affects autonomic nerves, lipolysis and appetite in rats. Neurosci. Lett. 2005, 383, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlahos, J. Scent and Sensibility. The New York Times 2007. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2007/09/09/realestate/keymagazine/909SCENT-txt.html (accessed on 29 June 2021).

- Štetka, P. Scent Marketing Alebo Aromamarketing. Útok Predajcov na Ďalší náš Zmysel. Štetka, P. 2012. Available online: https://peterstetka.wordpress.com/2012/12/09/scent-marketing-alebo-aromamarketing-utok-predajcov-na-dalsi-nas-zmysel/ (accessed on 29 June 2021).

- Berčík, J.; Paluchová, J.; Neomániová, K. Neurogastronomy as a tool for evaluating emotions and visual preferences of selected food served in different ways. Foods 2021, 10, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boesveldt, S.; de Graaf, K. The differential role of smell and taste for eating behavior. Perception 2017, 46, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The prisma 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar]

- Guéguen, N.; Petr, C. Odors and consumer behavior in a restaurant. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2006, 25, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, Y.; Inada, Y.; Yang, J.; Kunieda, S.; Masuda, T.; Kimura, A.; Kanazawa, S.; Yamaguchi, M.K. Infant visual preference for fruit enhanced by congruent in-season odor. Appetite 2012, 58, 1070–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berčí-k, J.; Palúchová, J.; Vietoris, V.; Horská, E. Placing of aroma compounds by food sales promotion in chosen services business. Potravin. Slovak J. Food Sci. 2016, 10, 672–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Leenders, M.A.A.M.; Smidts, A.; Haji, A.E. Ambient scent as a mood inducer in supermarkets: The role of scent intensity and time-pressure of shoppers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 48, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, D.; Szocs, C. The smell of healthy choices: Cross-modal sensory compensation effects of ambient scent on food purchases. J. Mark. Res. 2019, 56, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, A.; Morrin, M.; Sayin, E. Smellizing cookies and salivating: A focus on olfactory imagery. J. Consum. Res. 2013, 41, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M. Individual Differences in the Impact of Odor-Induced Emotions on Consumer Behavior. Ph.D. Thesis, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Knasko, S.C. Pleasant odors and congruency: Effects on approach behavior. Chem. Senses 1995, 20, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D.J.; Kahn, B.E.; Knasko, S.C. There’s something in the air: Effects of congruent or incongruent ambient odor on consumer decision making. J. Consum. Res. 1995, 22, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrin, M.; Ratneshwar, S. Does it make sense to use scents to enhance brand memory? J. Mark. Res. 2003, 40, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosmans, A. Scents and sensibility: When do (in)congruent ambient scents influence product evaluations? J. Mark. 2006, 70, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.; Sasaki, K.; Kunieda, S.; Wada, Y. Scents boost preference for novel fruits. Appetite 2014, 81, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firmin, M.W.; Gillette, A.L.; Hobbs, T.E.; Wu, D. Effects of olfactory sense on chocolate craving. Appetite 2016, 105, 700–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoon, H.F.A.; de Graaf, C.; Boesveldt, S. Food odours direct specific appetite. Foods 2016, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaekers, M.G.; Luning, P.A.; Lakemond, C.M.M.; van Boekel, M.A.J.S.; Gort, G.; Boesveldt, S. Food preference and appetite after switching between sweet and savoury odours in women. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spence, C.; Carvalho, F.M. The coffee drinking experience: Product extrinsic (atmospheric) influences on taste and choice. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 80, 103802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, C. Book review: ‘Neurogastronomy: How the brain creates flavor and why it matters’ by gordon m. Shepherd. Flavour 2012, 1, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebat, J.-C.; Michon, R. Impact of ambient odors on mall shoppers’ emotions, cognition, and spending: A test of competitive causal theories. J. Bus. Res. 2003, 56, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaekers, M.G.; Boesveldt, S.; Lakemond, C.M.; van Boekel, M.A.; Luning, P.A. Odors: Appetizing or satiating? Development of appetite during odor exposure over time. Int. J. Obes. 2014, 38, 650–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolls, B.J.; Rolls, E.T.; Rowe, E.A.; Sweeney, K. Sensory specific satiety in man. Physiol. Behav. 1981, 27, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowlis, S.; Shiv, B.; Wadhawa, M. Smelling Your Way to Satiety: Impact of Odor Satiation on Subsequent Consumption Related Behaviors; Angela, Y., Ed.; Advances in Consumer Research Volume 35; Association for Consumer Research; Lee and Dilip Soman: Duluth, MN, USA, 2008; pp. 169–172. [Google Scholar]

- Gaillet-Torrent, M.; Sulmont-Rossé, C.; Issanchou, S.; Chabanet, C.; Chambaron, S. Impact of a non-attentively perceived odour on subsequent food choices. Appetite 2014, 76, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bone, F.P.; Ellen, S.P. Scents in the marketplace: Explaining a fraction of olfaction. J. Retail. 1999, 75, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, K.D.; Desrochers, D.M. The use of scents to influence consumers: The sense of using scents to make cents. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 90, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardes, F.R.; Cronley, M.L.; Cline, T.W. Consumer Behavior, 2nd ed.; Cengage India: Noida, India, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Spangenberg, E.R.; Grohmann, B.; Sprott, D.E. It’s beginning to smell (and sound) a lot like christmas: The interactive effects of ambient scent and music in a retail setting. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 1583–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Morrin, M.; Ratneshwar, S. The impact of ambient scent on evaluation, attention, and memory for familiar and unfamiliar brands. J. Bus. Res. 2000, 49, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarczydɫo, B. Scents and elements of aroma marketing in building of an appropriate brand image. In Proceedings of the International Scentific Conference of the College of Management and Quality Sciences of the Cracow University of Economics, 4–6 June 2014; Andrzej Jaki, B.M., Ed.; Foundation of the Cracow University of Economics: Crakow, Poland, 2014; pp. 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Office, Legal Patent Meyer-Dulheuer MD Legal Patentanwälte PartG mbB U.P.A.T. Protecting Scent Trademarks (1): Practically Possible in the Us—Rather Difficult in the EU. 2012. Available online: https://legal-patent.com/trademark-law/scent-trademark-us-and-eu/ (accessed on 29 June 2021).

- APEX. Scents of Place: Airlines Apply Aromas for Passenger Comfort; The Airline Passenger Experience Association: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://apex.aero/articles/scents-place-airlines-apply-aromas-passenger-comfort/ (accessed on 29 June 2021).

- Zumaya, N.; Reyes, P.A.; Baruch Díaz Ramírez, J. La ciencia de la comida en los aviones. Rev. Cienc. 2021, 68, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; McCauley, C.; Rozin, P. Odor and affect: Individual differences in the impact of odor on liking for places, things and people. Chem. Senses 1999, 24, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Main Objectives | Findings | N | Characteristics of Participants | Material | Data Collected | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OBJECTIVE REAL BEHAVIOUR | |||||||

| 1 | Guéguen and Petr [22] | To know the effect of two classical aromas diffused in a restaurant in order to test their effect on consumers’ behaviour. | Lavender—but not lemon aroma—increased the length of stay of customers and the amount of purchasing, possibly linked to lavender relaxing effect. | 88 | Restaurant customers | Lemon and lavender scents in a pizzeria 17 pizzas, 4 types of meat, 3 fishes, and 4 salads. | Length of time and money spent at the pizzeria |

| 2 | Wada et al. [23] | To explore whether the ability to bind olfactory and visual information in object recognition is developed in infancy. The study explored the ability of infants to recognise the smell of daily foods, including strawberries and tomatoes. | Infants showed a preference for the strawberry picture when they smelled the congruent odour in strawberry season. This olfactory–visual binding effect disappeared while strawberries were out of season. | Study 1: 37 | Babies (6–8 month) | Non food (Digital photos of tomatoes and strawberries were taken for visual stimuli) | Infant looking time as assessed by recording |

| Study 2: 26 | Females | Pieces of chocolate, cake and stroopwafel, beef croquette, cheese cubes and crisps, slice of melon, an apple and strawberries, piece of cucumber, tomato salad and raw carrot, bread, croissants, and pancake. | Infant looking time as assessed by recording | ||||

| 3 | Berčí-k et al. [24] | How aroma influences customer purchasing decision (preferences) in chosen service provider through the tracking of daily sales of baked baguettes (Paninis) with using of aroma equipment; Aroma Dispenser. | The acquired values were baked baguettes sales in a chosen period including aromatic stimulus, as a form of sales promotion, provides only a minimal effect. Nevertheless, an effect of specific odour was noticed on total sale of Paninis but only a small increase, which cannot be considered as economically efficient. | Unknown (real restaurant customers) | Customers of sports bar | Baguettes (Panini) released scents: ‘crunchy bread’ and ‘chicken soup’ | Sales and preference for specific baguettes measured in real conditions |

| 4 | Leenders et al. [25] | To test the effects of a pleasant and congruent ambient scent at different intensity levels in a real supermarket on shoppers’ mood and their evaluations and in-store behaviours. To explore the moderating effects of shopper characteristics such as age and gender. | Shoppers tend to overestimate the amount of time spent shopping at lower intensity levels and underestimate time spent shopping at high scent intensity levels. The nature of the shopping trip is important because shoppers may be more or less aware of the ambiguous scent presence. In this case, grocery shoppers, there was ample variety in time pressure and age. | Unknown (real conditions) | Supermarket customers | Melon scent in a supermarket | Questionnaire: mood, overall evaluation of the store, and store environment. Real time spent in the store. Questionnaire on time pressure and pleasantness of the scent. |

| Study | Main objectives | Findings | N | Characteristics of Participants | Material | Data collected | |

| 5 | Biswas and Szocs [26] | This research examines the effects of food-related ambient scents (indulgent and non-indulgent) on children’s and adults’ food purchases/choices. It aims to evaluate whether the perception of a food scent may induce reward and so reduce the need to seek rewards from gustatory food consumption. | Extended exposure (of more than two minutes) to an indulgent food-related ambient scent (e.g., cookie scent) leads to lower purchases of unhealthy foods compared with no ambient scent or a non-indulgent food-related ambient scent (e.g., strawberry scent). The effects seem to be driven by cross-modal sensory compensation, whereby prolonged exposure to an indulgent/rewarding food scent induces pleasure in the reward circuitry, which in turn diminishes the desire for actual consumption of indulgent foods. Notably, the effects reverse with brief (<30 s) exposure to the scent. | Study 1: 900 | Middle School Students (middle school cafeteria) | Apple scent Pizza scents No scent | Sales of indulgent and non-indulgent foods under the three scenting conditions |

| Study 2: 61 | Laboratory consumer study | Cookies’ scent Strawberry scent | Questionnaire to choose either cookies or strawberries under both scenting conditions | ||||

| Study 3: Unknown | Customers at a supermarket | Chocolate chip cookies scent Strawberry scent | Collecting customer receipts to register items purchased | ||||

| Study 4: Unknown (Students from a major University) | University students | Cookies’ scent Strawberry scent | Questionnaire on food choice between indulgent and non-indulgent food | ||||

| Study 5: Unknown (Students with parental consent) | Middle School Students (middle school cafeteria) | Cookies’ scent Apple scent | Questionnaire about feelings and reward | ||||

| Study 6: Unknown (Students from a major University) | University students | Cookies’ scent Strawberry scent Tested for: high and low exposure time | Questionnaire on food choice between indulgent and non-indulgent food | ||||

| Study 7: Unknown (Students from a major University) | University students | Cookies’ scent Strawberry scent No scent | Scent identification capability Food choice scale between pizza and salad | ||||

| OBJECTIVE PHYSIOLOGICAL DATA | |||||||

| 6 | Krishna et al. [27] | Effect of scent, image, and both in consumer response. Consumer response is measured by salivation change (studies 1 and 2), actual food consumption (study 3), and self-reported desire to eat (study 4). | Imagined odours can enhance consumer response but only when the consumer creates a vivid visual mental representation of the odour referent. The results demonstrate the interactive effects of olfactory and visual imagery in generating approach behaviours to food cues in advertisements. Scents can enhance consumers’ responses. | Study 1: 59 | Undergraduate students | Non food (Advertised food products: chocolate chip cookies) | Salivation. |

| Study 2: 142 | Undergraduate students | Non food (Advertised food products: chocolate chip cookies) | Salivation | ||||

| Study 3: 226 | Undergraduate students | Non food (visual sensory input with a special focus on imagining pictures on food consumption). Cookies provided after the test | Food consumption | ||||

| Study 4: 170 | Undergraduate students | Scent of chocolate chip cookies with a picture of chocolate chip cookies in the print ad. | Self-reported desire to eat | ||||

| Study | Main objectives | Findings | N | Characteristics of Participants | Material | Data collected | |

| 7 | Lin [28] | The focus of this dissertation is to understand the role of olfaction (sense of smell) in consumer behaviour. | Unpleasant odours raised stronger emotions than pleasant ones. Enhanced olfactory sensitivity (Hyperosmics) and normal individuals reacted in different ways to pleasant and unpleasant odours. Odour conditions affected food choices in both groups of individuals. Scenting enhanced preference for healthier food choices. | Study 1: 26 | Students | Scents released from manufactured smell kits, Sniffin Sticks (Burghart, Germany), are utilised as odour stimuli. Twenty different odours are included. | Neuroimagery and questionnaire chemical sensitivity scale |

| Study 2: 60 | Students | 15 pleasant odour-associated pictures, 15 unpleasant odour-associated pictures and 10 non-odour-associated pictures. | Neuroimagery and questionnaire chemical sensitivity scale | ||||

| Study 3: 19 | Students | Non food (images of snacks) | Food choices questionnaire | ||||

| Study 4: 80 | Students | Non food (images of snacks) | Food choices questionnaire | ||||

| SUBJECTIVE DATA COLLECTION (EXPLICIT TEST) | |||||||

| 8 | Knasko [29] | Two hypotheses were proposed: (i) subjects exposed to pleasant odours will spend more time looking at the food slides and give the slides better scores and (ii) when the odour of the room is conceptually congruent with a food slide, the slide will be viewed longer and be given higher ratings. | The thematic relationship between the ambient room–odour and the content of the photographic food slides did not play a role in this study. Rather, the results suggest that pleasant odours may have some general effects on humans due to their hedonic value. Congruency enhances pleasantness. | 120 | Age between 18–35 | Non food (Slides with pictures: 6 chocolate items and 12 control slides of pine trees) | Questionnaires: mood, pleasantness, arousal, health symptoms (hunger and thirst) |

| 9 | Mitchell et al. [30] | To investigate the effects of pleasant ambient odours within two different decision-making contexts: (i) to examine how the congruency of the effects of ambient odour on the brands chosen and the related decision process and (ii) to investigate the effects of scent on multiple decisions. | Experiments 1 and 2 provided that the congruency of the odour with the target product class influences consumer decision making. When ambient odour was congruent with the product class, subjects spent more time processing the data. | 77 | Pennsylvania University Students | Chocolate assortments, and non-food test (flowers) | Questionnaires: memory and choice among chocolate assortments |

| 10 | Morrin and Ratneshwar [31] | To examine the relationship between ambient scent and brand memory in incidental learning task in which subjects were exposed to brand information through digital food photographs on a computer screen. Ambient scent was manipulated and stimulus viewing time was included. | It demonstrates that for studying the effects of ambient scent in marketing and consumer research settings, theory and methodological tools from cognitive psychology can be successfully adapted and applied to brand and product stimuli. | 90 | Students with good English level | Food spices plus non-food (brand recognition, other scents) | Questionnaire on food spices for pleasantness, liking, and appropriateness for food and beverages |

| Study | Main objectives | Findings | N | Characteristics of Participants | Material | Data collected | |

| 11 | Bosmans [32] | To research the effects of pleasant ambient scents on evaluations: (i) the congruence of the scent with the product, (ii) the salience of the scent, and (iii) consumers’ motivation to correct for extraneous influences. | Ambient scents strongly influenced customer evaluations. As long as ambient scents are congruent with the product, scents continue to affect consumers’ evaluations, even when their influence becomes salient or when consumers are sufficiently motivated to correct for extraneous influences. | Study 1: 80 | Undergraduate students | Orange | Questionnaire on product evaluation |

| Study 2: 118 | Undergraduate Students | Orange | Questionnaire on product evaluation | ||||

| Study 3: 75 | Undergraduate students | Banana, apple, or tomato | Questionnaire on product evaluation | ||||

| 12 | Yamada et al. [33] | To investigate whether olfactory information modulates the categorisation of visual objects and whether the preference for visual objects that correspond to olfactory information stems from the categorisation bias. Additionally, to elucidate these issues by using perceptible and imperceptible odour stimuli. | The authors employed morphed images of strawberries and tomatoes combined with their corresponding odorants as stimuli. Visual preference for novel fruits was based on both conscious and unconscious olfactory processing regarding edibility. There is an interaction between visual and olfactory information: odours did not affect categorisation but preference. | 56 | Students | Non food (pictures of tomato and strawberry) and scent release from subliminal to supraliminal | Questionnaire on evaluation and odour detection |

| 13 | Firmin et al. [34] | To assess the effect of the olfactory sense on chocolate craving in college females as influenced by fresh (critamint) or sweet (vanilla) scents | Inhaling a fresh scent reduced females’ craving levels; similarly, when a sweet scent was inhaled, the participants’ craving levels for chocolate food increased. These findings are potentially beneficial for women seeking weight loss. | 92 | Student age 18–22 | Non food (12 digital, coloured photographs of chocolate foods in the categories of chocolate cake, chocolate muffin, chocolate ice cream, and chocolate brownie). Fresh and sweet scents released for the evaluation | Place a ballot indicating craving level for chocolate |

| 14 | Zoon et al. [35] | To replicate the influence of olfactory cues on sensory-specific appetite for a certain taste category and extend those findings to energy-density categories of foods. Additionally, whether the hunger state plays a modulatory role in this effect. | Exposure to food odours increases appetite for congruent products, in terms of both taste and energy density, irrespective of hunger state. Food odours steer towards the intake of products with a congruent macronutrient composition. | 29 | Females | Pieces of chocolate, cake and stroopwafel, beef croquette, cheese cubes and crisps, slice of melon, an apple and strawberries, piece of cucumber, tomato salad and raw carrot, bread, croissants, and pancake. | Study conducted both under hunger and satiety conditions. Rating odour intensity, general appetite, and specific appetite for 15 foods |

| 15 | Ramaekers et al. [36] | To investigate how switching between sweet and savoury odours affects the appetite for sweets and savoury products | The appetite for the smelled food remained elevated during odour exposure, known as sensory-specific appetite, whereas the pleasantness of the odour decreased over time, previously termed olfactory sensory-specific satiety. The first minute of odour exposure may be of vital relevance for determining food preference. | 30 | Women | Cups with banana, meat, or water (no smell). Combinations (odourless/banana, odourless/meat, meat/banana, and banana/meat.) | Sequential exposure to two aromas, followed by appetite questionnaire and food preference |

| REVIEWS | |||||||

| Study | Main objectives | Findings | N | Characteristics of Participants | Material | Data collected | |

| 16 | Krishna [5] | This review article presents an overview of research on sensory perception. The review also points out areas where little research has been conducted; therefore, each additional paper has a greater chance of making a bigger difference and sparking further research. | Still remains a tremendous need for research within the domain of sensory marketing, and such research can be very impactful. | ||||

| 17 | Paluchová [2] | This chapter is a summary of how the smell sense works through odour perception and its impact on consumer emotions and purchase decisions. Smell and memory are close terms, and their relationship is explained. | Either in a laboratory or in real conditions, air quality has to be respected and adapted for research and for spending time in each store. | ||||

| 18 | Spence and Carvalho [37] | Review: To summarise the evidence documenting the impact of the environment on the coffee-drinking experience. To demonstrate how many different aspects of the environment influence people’s choice of what coffee to order/buy as well as what they think about the tasting experience. | The coffee-drinking experience (what we choose to drink and what we think about the experience) are influenced by product-extrinsic factors. There is a need to examine cross-cultural differences in consumers’ choices of coffee to determine motivations for coffee consumption in different cultures. | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Girona-Ruíz, D.; Cano-Lamadrid, M.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A.; López-Lluch, D.; Esther, S. Aromachology Related to Foods, Scientific Lines of Evidence: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6095. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11136095

Girona-Ruíz D, Cano-Lamadrid M, Carbonell-Barrachina ÁA, López-Lluch D, Esther S. Aromachology Related to Foods, Scientific Lines of Evidence: A Review. Applied Sciences. 2021; 11(13):6095. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11136095

Chicago/Turabian StyleGirona-Ruíz, Dámaris, Marina Cano-Lamadrid, Ángel Antonio Carbonell-Barrachina, David López-Lluch, and Sendra Esther. 2021. "Aromachology Related to Foods, Scientific Lines of Evidence: A Review" Applied Sciences 11, no. 13: 6095. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11136095

APA StyleGirona-Ruíz, D., Cano-Lamadrid, M., Carbonell-Barrachina, Á. A., López-Lluch, D., & Esther, S. (2021). Aromachology Related to Foods, Scientific Lines of Evidence: A Review. Applied Sciences, 11(13), 6095. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11136095