The Soundscape Hackathon as a Methodology to Accelerate Co-Creation of the Urban Public Space

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Hackathon Approach

2.1. Definition

2.2. Hackathon Topics

2.3. Hackathon Format

2.4. Benefits and Pitfalls

3. The Soundscape Hackathon Event

3.1. Overview

- select up to three of the environments given;

- create a sound environment that enhances the usability of a place and increases its engaging character through a better soundscape [6];

- assure that their ideas can be implemented and fit in real contexts;

- create their own tools or to use existing tools to generate the modified audiovisual scenes;

- use VR, audio rendering and/or auralization to demonstrate their idea to lay people.

3.2. Teams

3.3. Urban Soundscape Data Set

- R0008 The tranquil lawn on the McGill University Campus serves as a place to relax. Trees and bushes cover the traffic and people that pass by in the background. A constant and monotonous low-frequency noise due to the traffic can be heard, sporadically supplemented by a honking car or whistling birds.

- R0018 The Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway in Boston is a 1.6 km long linear park that encourages the sense of a shared community with gardens, promenades, fountains and art installations [29]. The busy area around the location of the recording is reflected in the audio recording by a constant low frequency traffic noise, honking, squeaky brakes, accelerating cars and talking people.

- R0032 Jinwan Plaza is a spacious square along the borders of the Hai river. The absence of traffic and the calming effect of the water make the spot well suited for a moment to escape from the busy city life. The soundscape mainly consists of low-level noise and some more salient but distant traffic events every once in a while.

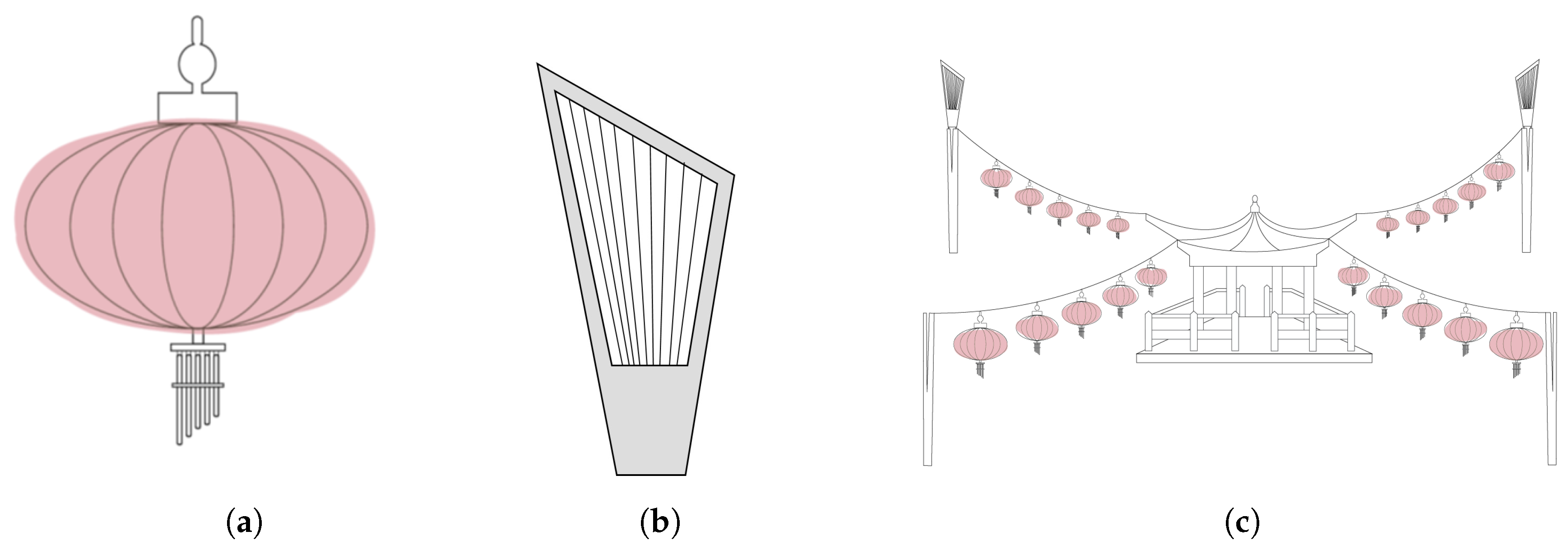

- R0043 Signal Hill Garden is a public park with a lot of natural green, combined with paved pathways, a Chinese pavilion and a panoramic view over Victoria Harbour. Although the garden itself is a calm environment with bird sounds and some periodic noise from garden maintenance, the proximity of industrial cranes and a road creates a rather noisy soundscape.

- R0063 With around 70.000 visitors a day, Potsdamer Platz is a very lively place and a thriving focal point at the heart of Berlin [30]. Inevitable this is reflected in the soundscape with a lot of talking people and a high amount of traffic with typical sounds such as honking, accelerating, motor sounds etc.

- R0064 City Hall Park is a small park alongside Broadway with a fountain, art installations and lots of benches, mainly used by tourists to have some rest in between visiting the 9/11 Memorial and crossing Brooklyn Bridge. Talking people can be heard but the main noise consists of typical traffic noises combined with some ongoing construction works.

- R0092 The Chicago Riverwalk is a public path along the Chicago River. The shade created by some trees and the presence of water attracts people to have a rest or to make a relaxing walk. Traffic noise and talking people can be perceived, but the recording is dominated by the sound of a tourist boat, including a guide providing touristic information.

- AT01 The city of Antwerp recently started the project ‘Tuinstraten’ (‘Garden streets’) in co-operation with the local community. In such a street the goal is to maximally replace existing pavements with trees, lawns, plant boxes, and other greenery as a measure for climate change and to improve the quality of life in the street [31]. The De Brouwerstraat is a small car-free street where the only thing that can be heard are some background noises and bird sounds.

3.4. Equipment

3.4.1. Art-Science-Interaction Lab (ASIL)

3.4.2. Maker Space

3.4.3. Audio Rendering Techniques

3.4.4. VR Systems

3.4.5. Software

3.5. Evaluation Criteria

- Creativity. What concept do the teams use to bring soundscape design to a broad public? Do they use new ideas and concepts, or existing approaches? How do teams cope with the different soundscapes provided? Which one(s) do they select and why?

- Theoretical soundness. Do the implemented adjustments sound correct? Is the modification physically possible and realistic? Do the suggested adjustments adhere to soundscape theory?

- Use of technology. How do the participants make use of the available technology in their designs? How do they use it to present their ideas? Do they combine different technologies? Is the selected technology suitable to present their idea?

3.6. Timeline

4. Results

4.1. Immensive

4.2. Noize Makers

4.3. Trio Akustiko

4.4. URCHI

5. Discussion

5.1. Hackathon Outcomes

5.2. Evaluation of the Event

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Foth, M. Participation, Co-Creation, and Public Space. J. Public Space 2017, 2, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacione, M. Urban liveability: A review. Urban Geogr. 1990, 11, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindvall, T.; Radford, E.P. Measurement of Annoyance Due to Exposure to Environmental Factors. The fourth Karolinska Institue symposium on environmental health. Environ. Res. 1973, 6, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellström, B. Noise Design: Architectural Modelling and the Aesthetics of Urban Acoustic Space. Ph.D. Thesis, Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden, September 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Olafsen, S. Using planning guidelines as a tool to achieve good soundscapes for residents. In Proceedings of the Inter-Noise 2009, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 23–26 August 2009; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- ISO Central Secretary. Acoustics—Soundscape—Part 1: Definition and Conceptual Framework; International Stand ISO 12913-1; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- De Coensel, B.; Bockstael, A.; Dekoninck, L.; Botteldooren, D.; Schulte-Fortkamp, B.; Kang, J.; Nilsson, M.E. The soundscape approach for early stage urban planning: A case study. In Proceedings of the Inter-Noise 2010, Lisbon, Portugal, 13–16 June 2010; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J. A systematic approach towards intentionally planning and designing soundscape in urban open public spaces. In Proceedings of the Inter-Noise 2007, Istanbul, Turkey, 28–31 August 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L.; Muhar, A. An approach to the acoustic design of outdoor space. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2004, 47, 827–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; De Coensel, B.; Filipan, K.; Aletta, F.; Van Renterghem, T.; De Pessemier, T.; Joseph, W.; Botteldooren, D. Classification of soundscapes of urban public open spaces. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 189, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiner, M.; Dalenbäck, B.I.; Svensson, P. Auralization—An Overview. JAES 1993, 41, 861–875. [Google Scholar]

- De Coensel, B.; Sun, K.; Botteldooren, D. Urban Soundscapes of the World: Selection and reproduction of urban acoustic environments with soundscape in mind. In Proceedings of the Inter-Noise 2017, Hong Kong, China, 27–30 August 2017; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Echevarria Sanchez, G.M.; Van Renterghem, T.; Sun, K.; De Coensel, B.; Botteldooren, D. Using Virtual Reality for assessing the role of noise in the audio-visual design of an urban public space. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 167, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffei, L.; Iachini, T.; Masullo, M.; Aletta, F.; Sorrentino, F.; Senese, V.; Ruotolo, F. The Effects of Vision-Related Aspects on Noise Perception of Wind Turbines in Quiet Areas. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 1681–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruotolo, F.; Maffei, L.; Di Gabriele, M.; Iachini, T.; Masullo, M.; Ruggiero, G.; Senese, V.P. Immersive virtual reality and environmental noise assessment: An innovative audio–visual approach. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2013, 41, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topi, H.; Tucker, A. Computing Handbook: Information Systems and Information Technology, 3rd ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-143-989-854-3. [Google Scholar]

- Leckart, S. The hackathon is on: pitching and programming the next killer app. Wired 2012. Available online: https://www.wired.com/2012/02/ff_hackathons/ (accessed on 19 July 2019).

- Jones, G.M.; Semel, B.; Le, A. “There’s no rules. It’s hackathon.”: Negotiating Commitment in a Context of Volatile Sociality. J. Linguist. Anthropol. 2015, 25, 322–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackathons by City. Available online: https://www.hackathon.com/city (accessed on 18 July 2019).

- Briscoe, G.; Mulligan, C. Digital Innovation: The Hackathon Phenomenon. 2014, p. 13. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/cb8e/44ec1bcd6062e5fccafb6837030be334731d.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2019).

- Groen, D.; Calderhead, B. Science hackathons for developing interdisciplinary research and collaborations. eLife 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- First Paper Hackathon on Computational Life Sciences: How Did It Go? Available online: http://www.2020science.net/news/first-paper-hackathon-computational-life-sciences-how-did-it-go.html (accessed on 29 July 2019).

- Groen, D. The First Science Paper Hackathon: How Did It Go? Available online: https://www.software.ac.uk/blog/2016-09-26-first-science-paper-hackathon-how-did-it-go (accessed on 29 July 2019).

- Ghouila, A.; Siwo, G.H.; Entfellner, J.B.D.; Panji, S.; Button-Simons, K.A.; Davis, S.Z.; Fadlelmola, F.M.; The DREAM of Malaria Hackathon Participants; Ferdig, M.T.; Mulder, N. Hackathons as a means of accelerating scientific discoveries and knowledge transfer. Genome Res. 2018, 28, 759–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- About Sana. Available online: https://sana.mit.edu/about (accessed on 29 July 2019).

- Angelidis, P.; Berman, L.; Casas-Perez, M.d.l.L.; Celi, L.A.; Dafoulas, G.E.; Dagan, A.; Escobar, B.; Lopez, D.M.; Noguez, J.; Osorio-Valencia, J.S.; et al. The hackathon model to spur innovation around global mHealth. J. Med. Eng. Technol. 2016, 40, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denis, V. Dark Side of Data Science Hackathons. Available online: https://towardsdatascience.com/dark-side-of-data-science-hackathons-1879b201d40c (accessed on 30 July 2019).

- Immensive. Available online: https://www.immensive.it/ (accessed on 17 July 2019).

- Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rose_Fitzgerald_Kennedy_Greenway (accessed on 3 July 2019).

- Potsdamer Platz. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Potsdamer_Platz (accessed on 4 July 2019).

- Pilootproject Tuinstraten. Available online: https://www.antwerpen.be/nl/info/59d738412d2a3cb90c44ccef/pilootproject-tuinstraten (accessed on 15 July 2019).

- IPEM’s Art-Science-Interaction Lab UGENT. Available online: https://www.ugent.be/lw/kunstwetenschappen/ipem/en/services/asil/overview.html (accessed on 28 June 2019).

- Moens, B. GitHub Repository: ArtScienceLab/ASIL_Documentation. 2020. Available online: https://github.com/ArtScienceLab/ASIL_Documentation (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- Rumsey, F. Audio Networking for the Pros. JAES 2009, 57, 271–275. [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens, J.; Spors, S. Implementation of Directional Sources In Wave Field Synthesis. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE Workshop on Applications of Signal Processing to Audio and Acoustics, New Paltz, NY, USA, 21 October 2007; pp. 66–69. [Google Scholar]

- Gerzon, M.A. Periphony: With-Height Sound Reproduction. JAES 1973, 21, 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens, J.; Wierstorf, H.; Spors, S. Comparison of Higher Order Ambisonics And Wave Field Synthesis With Respect to Spatial Discretization Artifacts in Time Domain. In Proceedings of the AES 40th International Conference, Tokyo, Japan, 8–10 October 2010; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Huygens, C. Traité de la lumière. Où sont expliquées les causes de ce qui luy arrive dans la reflexion, & dans la refraction. Et particulierment dans l’etrange refraction du cristal d’Islande, par C.H.D.Z. Avec un Discours de la cause de la pesanteur; Pierre Vander Aa, Marchand Libraire: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1690. [Google Scholar]

- Gergely, F.; Fiala, P. Spatial Aliasing and Loudspeaker Directivity in Unified Wave Field Synthesis Theory. Presented at the DAGA, Munchen, Germany, 19–22 March 2018; p. 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IOSONO Core. Available online: https://www.barco.com/en/product/iosono-core (accessed on 28 June 2019).

- Mauer, S.; Melchior, F.; Dausel, M. Design and integration of a 3D WFS System in a cinema environment including ceiling speakers—A case study. In Proceedings of the DAGA, Darmstadt, Germany, 19–22 March 2012; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Mauer, S.; Melchior, F. Design and Realization of a Reference Loudspeaker Panel for Wave Field Synthesis. In Proceedings of the 130th AES Convention, London, UK, 13–16 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, C. HTC Vive Pro vs. Oculus Rift: How Much Better Is the New VR Headset? Available online: https://www.windowscentral.com/htc-vive-pro-vs-oculus-rift (accessed on 1 August 2019).

- Ableton Live 10. 2018. Software. Available online: https://www.ableton.com/en/live/ (accessed on 3 April 2019).

- Cycling ’74. Max 7.3.5. Software. 2019. Available online: https://cycling74.com/downloads/older (accessed on 3 April 2019).

- Azkorra, Z.; Pérez, G.; Coma, J.; Cabeza, L.; Bures, S.; Álvaro, J.; Erkoreka, A.; Urrestarazu, M. Evaluation of green walls as a passive acoustic insulation system for buildings. Appl. Acoust. 2015, 89, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinmaster, M. Are Green Walls as “Green” as They Look? An Introduction to the Various Technologies and Ecological Benefits of Green Walls. J. Green Build. 2009, 4, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.Y.; Lee, P.J.; You, J.; Kang, J. Acoustical characteristics of water sounds for soundscape enhancement in urban open spaces. JASA 2012, 131, 2101–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Coensel, B.; Vanwetswinkel, S.; Botteldooren, D. Effects of natural sounds on the perception of road traffic noise. JASA 2011, 129, EL148–EL153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesura, A. The role of urban parks for the sustainable city. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 68, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, K.N.; Devine-Wright, P.; Payne, S.R.; Fuller, R.A.; Painter, B.; Gaston, K.J. Green space, soundscape and urban sustainability: An interdisciplinary, empirical study. Local Environ. 2009, 14, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipan, K.; Boes, M.; De Coensel, B.; Lavandier, C.; Delaitre, P.; Domitrovic, H.; Botteldooren, D. The personal viewpoint on the meaning of tranquility affects the appraisal of the urban park soundscape. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Team | Country | # Members | Affiliation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immensive | Italy | 3 | Immensive |

| Noize Makers | France | 4 | IFFSTAR; freelance |

| Trio Akustiko | Austria | 3 | TU Graz |

| URCHI | Spain | 4 | Universitat Pompeu Fabra; Universitat de Barcelona |

| ID | City (Country) | Location | YouTube Preview |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Coordinates) | |||

| R0008 | Montreal (CA) | McGill University Campus | https://bit.ly/2Nrj9gu |

| (45.504202,−73.576833) | |||

| R0018 | Boston (US) | Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy greenway | https://bit.ly/2XyRUo0 |

| (42.354721, −71.052073) | |||

| R0032 | Tianjin (CN) | Jinwan Plaza | https://bit.ly/2YeMdIZ |

| (39.131835, 117.202969) | |||

| R0043 | Hong Kong (HK) | Signal Hill Garden | https://bit.ly/2YgrDYx |

| (22.296008, 114.174859) | |||

| R0063 | Berlin (DE) | Potsdamer Platz Campus | https://bit.ly/2X9NzYV |

| (52.509192, 13.376332) | |||

| R0064 | New York (US) | City Hall | https://bit.ly/2XEqjS8 |

| (40.712014, −74.007495) | |||

| R0092 | Chicago (US) | River Walk - Arcade | https://bit.ly/2xcrVUy |

| (41.887138, −87.631663) | |||

| AT01 | Antwerp (BE) | De Brouwerstraat | https://bit.ly/2Lt24jD |

| (51.197695, 4.421701) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Winne, J.; Filipan, K.; Moens, B.; Devos, P.; Leman, M.; Botteldooren, D.; De Coensel, B. The Soundscape Hackathon as a Methodology to Accelerate Co-Creation of the Urban Public Space. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1932. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10061932

De Winne J, Filipan K, Moens B, Devos P, Leman M, Botteldooren D, De Coensel B. The Soundscape Hackathon as a Methodology to Accelerate Co-Creation of the Urban Public Space. Applied Sciences. 2020; 10(6):1932. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10061932

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Winne, Jorg, Karlo Filipan, Bart Moens, Paul Devos, Marc Leman, Dick Botteldooren, and Bert De Coensel. 2020. "The Soundscape Hackathon as a Methodology to Accelerate Co-Creation of the Urban Public Space" Applied Sciences 10, no. 6: 1932. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10061932

APA StyleDe Winne, J., Filipan, K., Moens, B., Devos, P., Leman, M., Botteldooren, D., & De Coensel, B. (2020). The Soundscape Hackathon as a Methodology to Accelerate Co-Creation of the Urban Public Space. Applied Sciences, 10(6), 1932. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10061932