Abstract

The city of Naples (Campanian region, Southern Italy) has been hit by the strongest earthquakes located inside the seismogenic areas of the Southern Apennines, as well as by the volcano-tectonic earthquakes of the surrounding areas of the Campi Flegrei, Ischia and Vesuvius volcanic districts. An analysis of the available seismic catalogues shows that in the last millennium, more than 100 earthquakes have struck Naples with intensities rating I to III on the Mercalli–Cancani–Sieberg (MCS) scale over the felt level. Ten of these events have exceeded the damage level, with a few of these possessing an intensity greater than VII MCS. The catastrophic earthquakes of 1456 (I0 = XI MCS), 1688 (I0 = XI MCS) and 1805 (I0 = X MCS) occurred in the Campania–Molise Apennines chain, produced devastating effects on the urban heritage of the city of Naples, reaching levels of damage equal to VIII MCS. In the 20th century, the city of Naples was hit by three strong earthquakes in 1930 (I0 = X MCS), 1962 (I0 = IX MCS) and 1980 (I0 = X MCS), all with epicenters in the Campania and Basilicata regions. The last one is still deeply engraved in the collective memory, having led to the deaths of nearly 3000 individuals and resulted in the near-total destruction of some Apennine villages. Moreover, the city of Naples has also been hit by ancient historical earthquakes that originated in the Campanian volcanic districts of Campi Flegrei, Vesuvio and Ischia, with intensities up to VII–VIII MCS (highest in the Vesuvian area). Based on the intensity and frequency of its past earthquakes, the city of Naples is currently classified in the second seismic category, meaning that it is characterized by “seismicity of medium energy”. In this paper, we determine the level of damage suffered by Naples and its monuments as a result of the strongest earthquakes that have hit the city throughout history, highlighting its repetitiveness in some areas. To this aim, we reconstructed the seismic history of some of the most representative urban monuments, using documentary and historical sources data related to the effects of strong earthquakes of the Southern Apennines on the city of Naples. The ultimate purpose of this study is to perform a seismic macro-zoning of the ancient center of city and reduce seismic risk. Our contribution represents an original elaboration on the existing literature by creating a damage-density map of the strongest earthquakes and highlighting, for the first time, the areas of the city of Naples that are most vulnerable to strong earthquakes in the future. These data could be of fundamental importance to the construction of detailed maps of seismic microzones. Our study contributes to the mitigation of seismic risk in the city of Naples, and provides useful advice that can be used to protect the historical heritage of Naples, whose historical center is a UNESCO World Heritage site.

1. Introduction

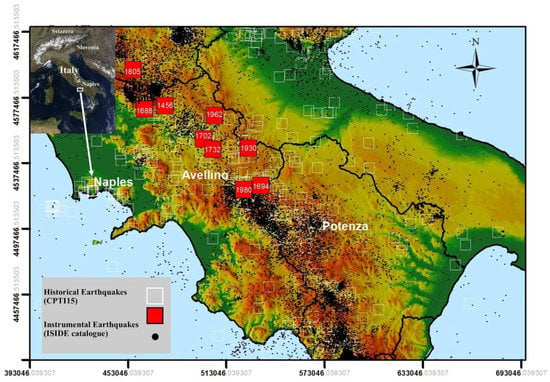

Since historical times, the central-southern Apennines chain has generated the strongest earthquakes in Italy. The epicenters of the most energetic events located along this chain have shown a significant alignment in the northwest-southeast direction, parallel to the main direction of the Apennines (Figure 1). The city of Naples has always been exposed to strong earthquakes, and these repeatedly have hit the Southern Apennines from the 15th century to the present (Appendix A Table A1) [1,2,3,4]. Our analysis of the available earthquake catalogues and relative scientific papers shows that more than 100 earthquakes with intensities of I > III Mercalli–Cancani–Sieberg (MCS) over the felt level hit the city of Naples in the last millennium. Ten of these events far exceeded the damage threshold, with intensities of VII MCS or greater [5,6,7]. The strong historical earthquakes that have struck the city since the 15th century (Figure 1) occurred in 1456 (I0 = XI MCS), 1688 (I0 = XI MCS), 1694 (I0 = X MCS), 1702 (I0 = X MCS), 1732 (I0 = X-XI MCS), 1805 (I0 = X MCS), 1930 (I0 = X MCS), 1962 (I0 = IX MCS) and 1980 (I0 = X MCS) [1,2,3]. Moreover, the city being located between two active volcanic districts, the Somma-Vesuvio to the East, and the Campi Flegrei volcanic field to the West, has been affected also by volcano-tectonic and volcanic earthquakes [8,9,10] even if characterized by low/moderate magnitude and shallow hypocenters (Appendix A Table A1).

Figure 1.

Map of historical earthquake locations (after CPTI15,14). The earthquakes felt in Naples are denoted with a red square, all others are denoted with a white square. The distributions of instrumental quakes from the Italian Seismological Instrumental and Parametric Data-Base (ISIDE) are represented by black dots.

Indeed, in early historical times, the most severe earthquakes to hit Naples originated from the Vesuvian area, including the 62 AD and 79 AD earthquakes [11], which had maximum intensities up to VII–VIII MCS. Naples was also affected by the seismicity related to the eruption of Vesuvio in 1631 [4,12] and more recently by the 9 October 1999 earthquake (Md = 3.6 [13]; Mw = 3.24 [14]). Additionally, Naples suffered from the Campi Flegrei earthquakes preceding and accompanying the eruption of Monte Nuovo in 1538 [5,15], and more recently was affected by the 4 October 1983 earthquake (M = 4.2 [3]) during the 1982–1984 bradyseismic crisis of Campi Flegrei.

In this paper we present an analysis of the damages that have occurred in Naples due to the strongest earthquakes located in Campania–Molise (Southern Apennines), but we do not take into account the damages of earthquakes that occurred in Vesuvio and Campi Flegrei, for which there is not as much detailed information as for the Apennines earthquakes. The aim is mainly to highlight local seismic hazards and potential heavy damage that could threaten the historical center of Naples and its rich architectural heritage. Based on the intensity and frequency of earthquakes that have occurred in the past, the city of Naples is ranked in the second seismic category, ‘average seismicity’ (Deliberazione Giunta Regionale n.5447 of 2012).The structure of this paper includes an introduction describing the most relevant seismic events that have hit the Neapolitan area, the object of the study, as well as geological structure of the city, highlighting its main characteristics and historical and architectural heritage. Section 2 describes the methodology applied in the study, in which the levels of damage to prestigious monuments of the Naples area are determined and then compared with a density map detailing areas of similar damage. Section 3 illustrates in detail the most important Apennines earthquakes that have hit the city of Naples, including detailed data that are collected in the Appendix A. In Section 4 we analyze and discuss the results of our study. Section 5 outlines the conclusions of our analysis.

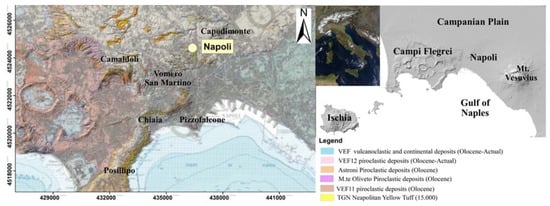

The city of Naples is located inside the Campanian Plain, a very large tectonic depression NW-SE elongated, that originated during the extensional regime following the formation of the Southern Apennines [16,17,18,19]. The Plain includes the Campi Flegrei and Somma-Vesuvio active volcanic districts to the west and southeast of the city, respectively. In particular, the most important explosive eruptions of the Campi Flegrei volcanic field produced the Campanian Ignimbrite (Figure 2) (Ignimbrite Campana (IC)) (39,000 years) and the Neapolitan Yellow Tuff (Tufo Giallo Napoletano (TGN)) (15,000 years) [20] lithoid tuffs that represented the main source rocks for most of the ancient and modern buildings inside the urban area of Naples.

Figure 2.

Geological Map of Naples extracted from the Geological Map of Italy, 1:50,000 (Sheet Naples n. 446–447).

The main reliefs of the urbanized area of Naples include ancient eruptive centers originating the hills of Capodimonte, Vomero, Pizzofalcone, Posillipo and Camaldoli (Figure 2). These were the results of activity from about 70 explosive monogenetic volcanoes as well as down-faulting displacement associated with the collapse of the Campi Flegrei caldera [21,22].

The very intense urbanization of Naples has been almost continuous over time, and architectural development and consequent anthropic activities have nowadays hidden the ancient eruptive centers, making their relative volcanic morphologies rather undetectable.

The stratigraphic setting of the urban area is very complex and mainly characterized by a cover of loose pyroclastic and reworked material lying on Neapolitan Yellow Tuff (TGN) sequence, with lateral and vertical heterogeneities due to the presence of different erupted products, and vertical and lateral variation in lithification grades [23].

The main outcropping deposits in the urban area of Naples, as regards the areal extension, are pyroclastic ashes, lapilli and pumice dating less than 15,000 years, which therefore erupted after the TGN setting, as well as some reworked pyroclastics, as shown on the Geological Map of Naples (Figure 2) [24]. The litified deposits of IC and TGN very rarely outcrop inside the urban area.

As the city of Naples is located next to the western area of the Southern Apennines, it has consistently been exposed to the strong historical earthquakes that repeatedly have hit the mountain chain and its villages. Moreover, as the city is enclosed by two great active volcanic districts (i.e., the Somma-Vesuvio and Campi Flegrei volcanic fields), it has also been affected by the seismic activity (even at low/moderate magnitudes) of volcano-tectonic and volcanic earthquakes, an issue that persists to the present day [20,25,26,27]. In particular, the Campi Flegrei area, near the city, has undergone considerable deformations and almost continuous subsidence due to several bradyseismic phases over the past two millennia [28].

Settlements in the Gulf of Naples date back to a very ancient age due to its mild climate, the fertility of its soil and its abundance of landings and natural harbors.

The city has been influenced in its urban development by the arrival of various peoples and cultures, from its Greek foundations, Roman conquest, Byzantine domination, Norman and Swabian dominations and alternating French and Spanish dynasties to the present era [29,30]. Such multiethnic influence has given Naples a unique reality that is rich in history and culture both in terms of its the urban layout as well as its art and traditions. The historic center of Naples represents an exclusive example of a vertical stratified city, and its architecture is based on overlapping of different architectural styles [31]. It has been possible to reconstruct the historical events of many parts of the city with greater precision due to the numerous archaeological findings that have been found over the years. Parthenope, the first nucleus of the future Naples, was founded by the Cumans in the eighth century BC on Echia Mountain, and is presently known as Pizzofalcone [32].

The harbor was located to the east of the city, near the present-day Municipio Square, and there Castel Nuovo (as known as Maschio Angioino) became the headquarters of the medieval age and one of the most important symbols of the city. At the beginning of the sixth century BC, the city was rebuilt as Neapolis, meaning “new city”, and was conceived similarly to the city of Cuma [32]. Due to the privileged relationship with Athens, Naples became one of the largest ports in the Mediterranean Sea, with unchanged urban development until the middle of the first century BC [33]. Following the influences of Athens and Syracuse, the political and social equilibrium of Naples was compromised towards the end of the fifth century BC by the expansion of the Oscii people, who conquered both the territories of the Etruscans in northern Campania and the territories of the Cumans [32]. In 327 BC, the city of Naples was strongly contended between the Sanniti and Romans. Rome had the strongest influence, reducing the city’s Greek traditions and habits [32]. From the first century BC until approximately the first century AD, Roman high society went to Naples for rest and recreation. It was precisely in this period that Naples was enriched with refined Roman villas. In the Augustan age, Naples was hit with the catastrophic earthquakes of 62 AD and 79 AD and the eruption of Vesuvius [2,34,35].

Many churches were built during the empire of Constantine in the fourth century, such as San Giovanni Maggiore and San Giorgio Maggiore. In 533 AD, the church of Santa Maria Maggiore alla Pietrasanta was built in the historical center of Naples [36,37].

Naples was the attracted the attention of the Byzantine and Gothic peoples following the crisis of the Roman empire. The Byzantines conquered Naples in 534 AD, and thereafter became a Byzantine province for the next six centuries, during which the Duchy of Naples was established. Numerous monasteries were built in the city during this time, including the Greek monastery of San Sebastiano. Moreover, several churches were located on the hills of the interior or on the islands, such as the hill of Monte Echia or the islet of Megaride. Between 780 and 790 AD [37], the Byzantine bishop Stephen II built the church of San Gaudioso [36,37]. In the centuries of ducal government, Naples often found itself in contrast with the Lombards and Saracens and also had to face repeated contrasts with the pontifical state. The defensive wall was enlarged to protect Naples against attacks and heavy population growth. In the 9th and 10th centuries, the churches of Santi Severino e Sossio (10th century) and Santa Maria Donnalbina were built. In 1137, the Duchy was conquered by the Normans who later formed the Kingdom of Sicily.

Guglielmo I of Sicilia was responsible for the construction of Castel Capuano (1176) and for the restoration and expansion of Castel dell’ Ovo by building the tower later known as Normandy.

After the Norman period, Naples was subjected to Swabian domination. Thanks to Federico II of Swabia, Naples regained strong central power, thanks in particular to the establishment of the first State University of History.

During the subsequent Angevin domination, Charles I and Charles II of Anjou reorganized the city of Naples, with urban planning interventions aimed at creating a port city [38].

At the end of the 13th and beginning of the 14th centuries, numerous churches were built as a result of kings’ subsidies [29,30,36,37], including the churches of San Agrippino (1265), San Lorenzo Maggiore (1270), Santa Maria La Nova (1279), San Domenico Maggiore (1283), Sant’ Agostino Maggiore (1287) and San Pietro Martire (1294), the monastery of Santa Chiara (1310) and the Santa Maria Assunta Cathedral (1270–1313). In addition, Charles I of Anjou was responsible for the construction of a new fortress, Castel Nuovo (known as Maschio Angioino) (1279), which was located by the sea, right near the creek that previously hosted the port of Naples. The construction of the Santa Maria del Carmine church dates back to the end of the 13th century, thanks to the contributions of Roberto d’ Angio’ who donated the land in 1270, although historical sources report the date of the start of construction as the 12th century [36,37]. During the Angevin domination, the church of Santissima Annunziata Maggiore (1318, but completely rebuilt and enlarged in 1513), Castel Sant’Elmo (1329–1343), Certosa di San Martino (1325–1368, located at Vomero hill) and Castello del Carmine (1382) were built [36,37].

During the Catalan–Aragonese kingdoms (15th century), the church of Santa Maria di Monteoliveto (Sant’Anna dei Lombardi) was built (1411) and subsequently enlarged during the kingdom of Alfonso V of Aragona. He also restored Castel Nuovo, which had been damaged by continuous wars, and added an exemplary Triumph Arch and the famous throne room. Subsequently, the city of Naples underwent considerable expansion, with the construction of a new wall with 22 cylindrical towers [36,37]. Alfonso V of Aragona made the city of Naples a true capital of the Mediterranean [29,30]. During the Ferdinando kingdom, many monuments were built [39]: Palazzo Carafa d’Andria (in the early 15th century), Porta Capuana (1484), the Como Palace (Museo Filangieri) (1464 and 1490), the Diomede Carafa Palace (1470) and the facade of the San Severino palace (about 1470) of the Salerno princes. The currently facade of the church of Gesù Nuovo was rebuilt in 1584, as well as the actual lower church of Santi Severino e Sossio (1490). The urban situation is described in detail in the Tavola Strozzi dated at the end of 15th century (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Tavola Strozzi: view of Naples depicting the Aragonese fleet re-entering the port on 12 July 1465 after the defeat of the Angevin Navy at Ischia on 7 July. (Attributed to F. Rosselli—Museo Nazionale di San Martino, Naples, Italy.)

Between the 16th and 17th centuries, the fortification walls were built to the south of Naples [29,30]. Under Spanish domination, the kingdom of Carlo V (and the regency of his viceroy Don Pedro de Toledo) subjected Naples to further transformations in which the quarters of Toledo and the present Spanish quarters were built, in order to accommodate the Spanish military garrisons. At the beginning of the 16th century further work of transformation and fortification of Castel Nuovo (Maschio Angioino) and the construction of Palazzo Pignatelli di Monteleone were made by the Bourbons. During the 16th and 17th centuries, the churches of Gesù Vecchio dell’Immacolata di Don Placido (1554), San Tommaso d’Aquino (1567 but destroyed in 1932), San Liguoro/San Gregorio Armeno (1572), San Severo out of the walls (1573), Gesù Nuovo (1584), Madonna della Pietà dei Turchini (1592), San Filippo Neri (Gerolamini) (1592), San Filippo e Giacomo (1593), San Paolo Maggiore (1538–1630), Santa Maria della Sanità or San Vincenzo (1602–1614), Santa Maria della Verità/Sant’Agostino degli Scalzi (1603), Santa Maria ai Monti (1606–1654), Santa Teresa degli Scalzi (1604), San Michele Arcangelo dei Mercedari a Port’Alba (1620), San Nicola alla Carità (1647) and la Croce di Lucca were built [36,37]. Construction of the Regio Arsenal dates back to 1577, but it was destroyed in the early 1900s, while the construction of Palazzo Carafa di Maddaloni is dated to 1580. In the 17th century, the Church of Santa Maria Donnalbina (ninth century) and the Church of Santa Maria Maggiore alla Pietrasanta (sixth century) were rebuilt, and in 1667 the construction of the Presidio di Pizzofalcone began. In 1600, the building of the Palazzo Reale (Royal Palace) took place [39], and was subsequently expanded in 1734 when Naples became the capital of the kingdom with Charles III of Bourbon. The final transformations took place in Ferdinand’s time between 1838 and 1858 with a general restoration of the neoclassical style. In 1919 this was largely dedicated to the National Library, where the oldest wing was used as a Museum of Historic Property.

During the 20th century, many other changes and renovations were carried out, both in the Municipio Square and in the oldest city center [30].

As can be seen from the synthetic historical and architectural excursus reported so far, the uniqueness of Naples and above all of its historical center stems largely from the use of the ancient Greek path of road that has been preserved to the present day. Because of this, the historic center of Naples was declared a human heritage site in 1995 by UNESCO, and was included on its list of protected properties.

Our analysis has allowed us to reconstruct the seismic history of some of the most representative urban monuments of Naples, and to perform a seismic macro-zoning of the ancient center of the city in order to reduce future seismic risk. A methodology already widely tested for assessing the damage level of some cities affected by both historical and relatively more recent earthquakes was adopted [40,41].

2. Methodology

In the last 1000 years, the Southern Apennines have been the source area of strong earthquakes that have had a considerable impact on the city of Naples, exceeding the threshold of damage. In this paper we consider the level of damage suffered by the city of Naples and its monuments as a result of the strongest earthquakes that have affected it throughout its history, highlighting recurrences in some areas. We reconstructed the seismic history of some of the most representative urban monuments in Naples using a methodology already widely tested that assesses the damage level of cities that have been affected both historically and relatively more recently by earthquakes [5]. We determined the level of damage in certain Neapolitan structures relative to historical earthquakes, distinguishing three different classes of damage (Table 1): minor damage (MD) (slight damage; surface cracks, light non-structural damage); serious damage (SD) (large and extensive cracks, moderate structural damage, heavy non-structural damage and occasionally partial collapses); and great damage/collapse (GD) (heavy cracks, very heavy damage, heavy structural damage, partial and in some case total collapse).

Table 1.

Level of damage by historical earthquakes, distinguishing among three different classes of damage.

The classification of damage suffered by buildings of Naples was carried out by means of the expressions and terms used in the historical sources (i.e., “leviter lesa”, “leggiermente lesa” and ”picciola parte patita” for minor damage; “plurimum laceratum” and ”tutto lesionato” for serious damage; and “a fundamentis devastatum”, “gittato a terra” and “totalmente rovinato” for great damage). This analysis was possible thanks to the damage descriptions by several authors who used recurring verbs, adjective and adverbs that defined increasing damage levels [40,41,42,43,44,45].

For each earthquake studied in this paper, tables are presented in the Appendix A that show the original name of the monument whose damage is known, the type of building, the year of construction (and in some cases reconstruction), the level of damage suffered following the earthquake and the geographic coordinates. The damage reported by all buildings was mapped for each earthquake examined (Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6). Moreover, we generated a density map allowing the identification of areas with the same damage value for all examined historical earthquakes. For this purpose, we used the ArcGIS (version 10.8) Silverman algorithm, which calculates a magnitude-per-unit area from point features that fall within a neighborhood around each cell [46].

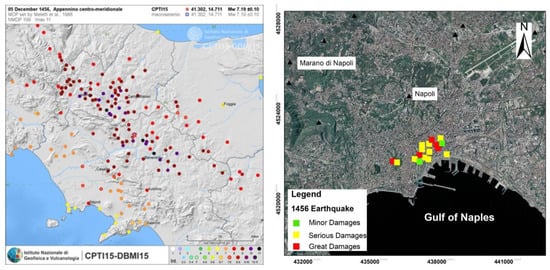

Figure 4.

Map of the 1456 Mercalli-Cancani-Sieberg (MCS) macroseismic intensity (modified from [1]) on the left; map of the damage to Naples from the earthquake of 5 December 1456 on the right.

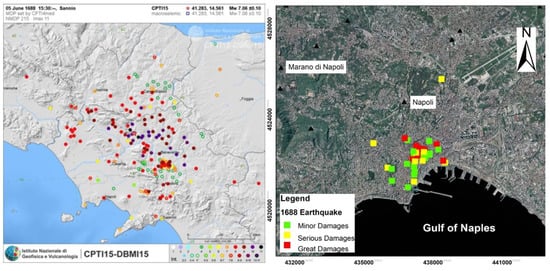

Figure 5.

Map of the 1688 MCS macroseismic intensity (modified from [1]) on the left; map of the damage to Naples from the earthquake of 5 June 1688 on the right.

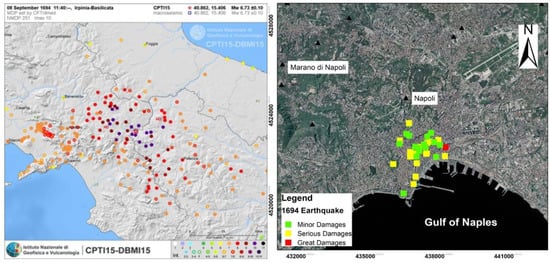

Figure 6.

Map of the 1694 MCS macroseismic intensity (modified from [1]) on the left; map of the damage to Naples from the earthquake of 8 September 1694 on the right.

The final results were interpreted and are commented upon in this paper, with a discussion of the usefulness and value of our study to improving the literature about seismic risk in the city of Naples.

3. Historical Earthquakes of the Southern Apennines Felt in Naples

The strongest historical earthquakes to have struck the city of Naples since the beginning of the 15th century (Figure 1) were in 1456 (I0 = XI MCS), 1688 (I0 = XI MCS), 1694 (I0 = X MCS), 1702 (I0 = X MCS), 1732 (I0 = X-XI MCS), 1805 (I0 = X MCS), 1930 (I0 = X MCS), 1962 (I0 = IX MCS) and 1980 (I0 = X MCS) [1,2,3]. Devastating effects were inflicted upon the historical Neapolitan urban area as a result of these seismic events, and damages reaching levels of up to VIII MCS have been recorded [6,7].

During the 20th century, the city of Naples was hit by three major earthquakes (in 1930, 1962 and 1980) originating in the Southern Apennines. The last of these events is still deeply engraved in the collective memory, due to the high number of casualties, of about 3000, and the almost complete destruction of some nearby Apennines villages.

The main seismological and macroseismic parameters of the earthquakes that hit the city of Naples in the previous centuries are listed in Appendix A Table A1. Between 1293 and 2002, 178 recorded events hit Naples, about ninety of which had an epicentral intensity of I0 >= VII MCS. Ten events struck Naples severely, exceeding a damage level greater than VII MCS [6,7]. The 5 December 1456 earthquake is considered one of the most catastrophic events to have occurred in Italy during historical times, and had an epicentral intensity of XI MCS and a magnitude Mw = 7.2 [14,42]. It was a very complex event, with five main shocks triggered along the axis of the Apennines [47] along a narrow belt ranging from the Abruzzi to Campania regions. The seismogenic area inside Benevento province was the nearest to Naples, and caused high levels of damage. The earthquake’s destruction covered a large region (Figure 4), with an intensity I≥ IX MCS and more than 90 localities affected in Central and Southern Italy, killing at least 60,000 people. In Naples, the earthquake resulted in 100 casualties. Damages were widespread, many buildings were damaged and streets were blocked. Historical sources report that damage occurred above all to the most important castles, fortresses, churches and monasteries of the time (Appendix A Table A2). Great and serious damages were recorded in Naples (Figure 4). In detail, collapses occurred in Castel Sant’Elmo, Castel Capuano and the churches of San Agostino, San Pietro Martire, San Lorenzo, Santa Chiara, San Giovanni Maggiore, Santa Maria Maggiore alla Pietrasanta, San Domenico and San Severino. Moreover, even the bell towers of San Agrippino and the Cathedral fell down; the Certosas of San Martino and Monte Oliveto monasteries, located outside the walls, were severely damage (Appendix A Table A2). The severity of the impact in the city of Naples was estimated to be equal to VIII MCS [5,42,47].

Another devastating earthquake that affected the whole Campania region occurred on 5 June 1688, with its epicenter inside the Sannio area (Figure 5). This earthquake was characterized by an epicentral intensity of I0 = XI MCS, presumably in the Cerreto Sannita and Civitella Licinio villages, and a value of magnitude Mw = 7.06 and I0 = X on the basis of the Environmental Seismic Intensity (ESI-07) scale [48]. The earthquake resulted in a high number of casualties, with some chronicles reporting as many as 10,000 deaths. Moreover, many environmental effects such as fractures, landslides, liquefaction phenomena and hydrological variations were observed that in some cases, together with the diffuse damage to the housing stock, led to total relocation of some Apennines villages like Cerreto Sannita [6,48]. The level of damage was very high throughout Naples (Figure 5), with a number of deaths somewhere between 35 and 50 people. Chronicles have reported severe and widespread damage, especially to the churches of the city (Appendix A Table A3). Of the church of San Paolo, an anonymous contemporary source reported that “in the atrium below the Church of San Paolo dei Teatini … the magnificent arch has dropped together with the large and ancient columns, which they were said to form the famous temple of Castor and Pollux, only four left standing, but almost falling, so far 19 people have been quarried from ruin”.

The collapse of the frames of some private buildings and damages to Castel Sant’Elmo, Castel Capuano, Castel Nuovo, the fortress of Torrione del Carmine, the Sala del Tesoro and the Royal Palace also occurred. The last revision proposed by the authors of DBMI15 [1] assigned a VIII MCS to Naples.

On 8 September 1694, a strong earthquake struck a wide area of Southern Italy between the Campania and Basilicata regions. Unlike the 1456 and 1688 earthquakes, the epicentral area was located between Irpinia and Basilicata (Figure 6), with I0 = X MCS, Mw = 6.73 and I0 = X ESI-07 [43,48,49]. The seismogenic source located in Campania and Basilicata, relatively more distant than the source zones of the 1456 and 1688 earthquakes, caused a lower damage level in Naples (Figure 6), evaluated as VII MCS. The number of deaths was considerable, about 6000 in total, although only one dead and one wounded were reported in Naples. The earthquake caused moderate damage throughout the Neapolitan urban fabric, with only a single collapse at Porta Nolana. Widespread damage occurred to the ecclesiastical buildings (Appendix A Table A4), and more or less serious damages occurred to the Cathedral and the churches of Girolamini, Santa Maria Maggiore, San Paolo Maggiore dei Teatini, Santi Severino e Sossio churches, among others. Much damage to public buildings was observed, including to Castel Nuovo (Maschio Angioino) and Castel Capuano. In the Royal Arsenal, seven arches and its central pillars lanes were damaged, while the Real Presidio of Pizzofalcone, which was already undergoing repairs, suffered damage to some walls that had to be reinforced with iron chains. Moreover, the noble palaces of the Duke Carafa of Maddaloni, the Duke Carafa of Andria and of the Duke Pignatelli of Monteleone suffered considerable damage.

In the following century, the city of Naples was hit by two strong events that took place on 14 March 1702 and 29 November 1732; both these epicenters were located between the Irpinia and Sannio areas, with damage levels evaluated to have an intensities of VI and VII MCS, respectively.

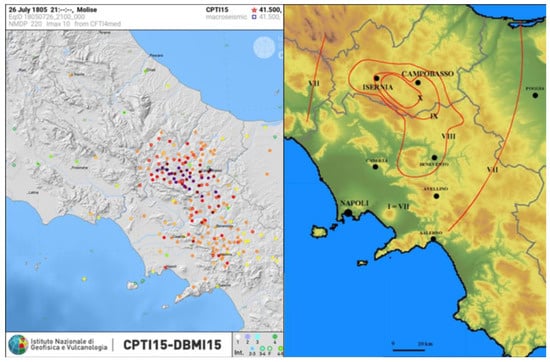

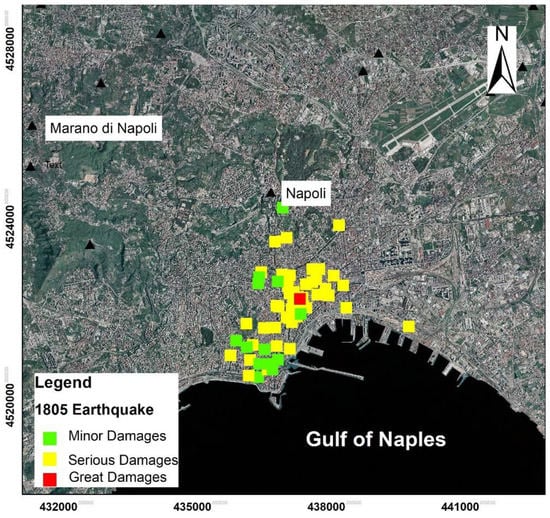

The 26 July 1805 earthquake is also known as “the earthquake of Sant’Anna”, since it occurred on the day dedicated to celebrating this saint. The epicentral area was located in the Molise region (Figure 7), where at least 19 villages suffered almost complete destruction, with epicentral intensity I0 = X MCS, Mw = 6.73 and I0 = X ESI-07 (Figure 7) [48,50]. According to official chronicles, 5573 people died and 1583 were injured. There was widespread damage in Naples (Figure 8), with collapses and deep fractures requiring shoring of housing. The damage level was equal to VII–VIII MCS (Appendix A Table A1). The major damages were related to part of today’s historical center (Appendix A Table A5) [44]. Indeed, Castel Nuovo (Maschio Angioino), the big building of Regj Studj, the Reale Albergo de’ Poveri, the Gesù Vecchio Church and the buildings of the Prince of Angri, of Roccella, of Sangro, of Duca della Regina and many others over the district of Pizzofalcone suffered serious damage. Moreover, some churches like the Cathedral, Sant’Agostino alla Zecca and San Demetrio also suffered severe damages. The strong earthquake produced many environmental effects throughout the whole area hit by the quake, especially in the epicentral area of the Bojano plain, with surface faulting, fractures, landslides and hydrological variations. In the Bay of Naples and along the coastal areas of Gaeta (in Latium) and Sorrento peninsula (in Campania), located very far from the epicentral area, changes in sea level equivalent to a low-energy tsunami were observed [45,48,50,51].

Figure 7.

Map of the 1805 MCS macroseismic intensity (modified from [1]) on the left; isoseismal map of the 1805 Bojano earthquake (modified from [50]) on the right.

Figure 8.

Map of damages caused in Naples by the 26 July 1805 earthquake.

In the 20th century, three catastrophic earthquakes with I0 ≥ IX MCS occurred in one of the main seismogenic zones located in the Southern Apennines. Events on 23 July 1930 and 21 August 1962 occurred in Irpinia; the earthquake of 23 November 1980 occurred at the border between Irpinia and Basilicata.

The 1930 earthquake struck the Campania, Puglia and Basilicata regions. The epicentral area was located between the northern Irpinia and Puglia regions, with I0 = X MCS, 6.67 Mw and I0 = X ESI-07 scale [14,48,51,52,53,54]. The most damaged villages were located along the axis of the Apennines Chain, including Ariano Irpino, Lacedonia, Villanova del Battista, Scampitella, Trevico and Aquilonia, with values of I = IX-X MCS. The earthquake led to the deaths of 1424 people, with 4624 injured and about 100,000 being left homeless in the aftermath.

In Naples, widespread damage occurred to housing stock and, in particular, four houses in the Courts area collapsed as well as the Casanova Bridge, with four casualties. The intensity value in Naples was VII MCS.

On 21 August 1962, a violent earthquake of Mw = 6.15 struck Campania, on the border between the Sannio and Irpinia regions, with an epicentral intensity of IX MCS [14,55]. The most affected towns were Ariano Irpino, Casalbore, Melito Irpino and Montecalvo Irpino in the province of Avellino; and Apice, Ginestra degli Schiavoni, Molinara, Reino and San Giorgio la Molara in the province of Benevento. The event was characterized by some premonitory shocks that deterred people from staying inside of their homes, ultimately reducing the number of deaths to only 17.

In the city of Naples, the earthquake resulted in five deaths, only one of which was a direct consequence of collapse. Moreover, there were collapses in the gutters of some buildings and serious damage to the Duca D’Aosta and Thaon de Revel dam, as well as to the Calata Villa del Popolo and Vittorio Veneto docks. Minor damages were widely observed in the historical center, and in the Vomero hilly zone. The intensity values assigned to Naples were VI–VII MCS.

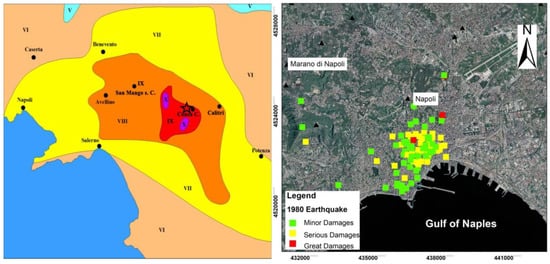

The final catastrophic event to devastate Southern Italy over the past 100 years is known as the Irpinia-Lucania earthquake, and it occurred on 23 November 1980 (Figure 1). It was characterized by an I0 = X MCS (Figure 9), Mw = 6.9 and I = X ESI [14,48,56]. It was felt throughout Italy, from southern Sicily in the South, to Emilia Romagna and Liguria in the North, with the epicenter between the Campania and Basilicata regions, which were the most damaged regions. The number of destroyed homes was 75,000, while about 275,000 were seriously damaged. The earthquake led to a loss of nearly 3000 lives and damage to about 800 villages. Castel Nuovo di Conza, Conza della Campania, Lioni, Santomenna, San Mango sul Calore, San Michele di Serino and Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi were almost completely destroyed. In Naples, this event produced widespread and serious damages (Figure 9), reaching an intensity of VII MCS [56]. About 18,000 stability analyses were carried out throughout the city, equal to 80–85% of the entire housing stock. The most damaged areas were found in the old city (Appendix A Table A6) [5,6,7,56,57,58].

Figure 9.

Isoseismal map of the November 1980 Irpinia-Basilicata earthquake [59] (on the left). The different colors are related to the different values of MCS macroseismic intensity, and the black star is the location of the epicenter. Map of the damage caused in Naples by the earthquake on 23 November 1980 (on the right).

A residential tower collapsed in the Poggioreale area, where 52 people were killed. Among the most important monumental buildings seriously damaged by the earthquake was the Reale Albergo dei Poveri (one of the largest in Europe), where the infirmary, part of the refectory and some of the surrounding rooms on the first and second floor collapsed [56].

4. Results and Discussion

The strongest earthquakes of the Southern Apennines, such as those in 1456 (Imax = XI MCS, Mw = 7.2), 1688 (Imax = X MCS, Mw = 6.7) and 1805 (Imax = X MCS, Mw = 6.7), reached Naples at a maximum macroseismic intensity of I = VIII on the MCS scale, with considerable damage to the architectural heritage of the historical center specifically, as in the case of Castel Nuovo, as well as to to the ecclesiastical heritage more generally. Meanwhile, the earthquakes of 8 September 1694, 23 July 1930 and 23 November 1980 caused a lower damage level of VII MCS in the urban area of Naples (Appendix A Table A1).

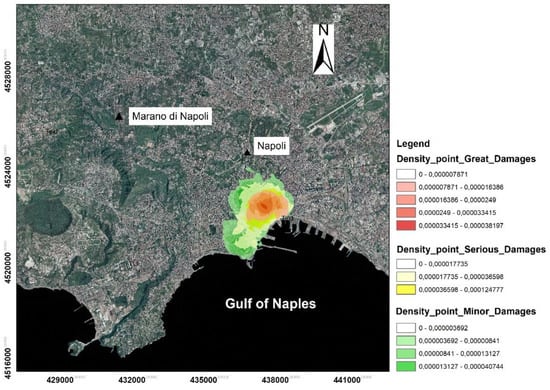

We distinguished the levels of damage relative to historical earthquakes as belonging to three different classes of damage: minor damage (MD), serious damage (SD) and great damage/collapse (GD). In detail, the levels of damage of the 1456 and 1688 earthquakes were great and serious, concentrated in a very restricted area of the historical center of Naples (Figure 4 and Figure 5, respectively). The 1805 earthquake resulted in a serious level of damage spread over a wider area of the historical center of the city (Figure 8), while the 1980 earthquake produced a serious level of damage that was widespread (Figure 9) in the historical center but also included minor damage diffused in the suburban areas (Figure 9). According to the different effects that the earthquakes had on the historical buildings of Naples, an original damage-density map has been elaborated upon in this paper (Figure 10), synthesizing all of the damage data on the architectural heritage that were collected ad hoc for comparison in our study. Figure 10 shows the way in which the damage repeats and overlaps in the same areas, with the greatest damages in the historic center of Naples covering an area of 17 km2 and representing the most vulnerable portion of the city.

Figure 10.

The map shows the areas with the same damage, represented as a density value, for all historical earthquakes felt in the city of Naples.

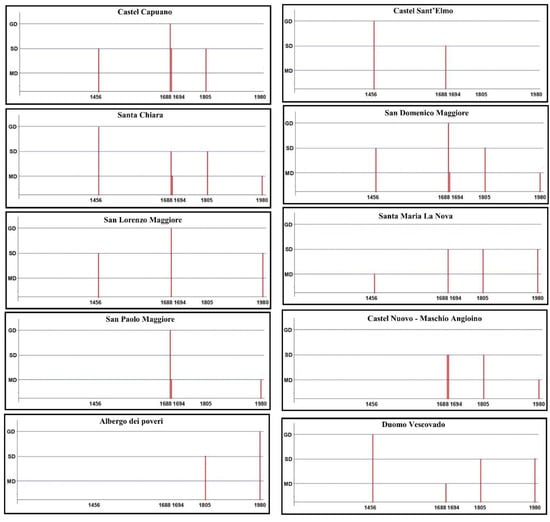

Several pieces of the most famous Neapolitan architectural heritage are located in this area, including the castles/fortresses of Castel Capuano, Castel Nuovo (Maschio Angioino) and Castel Sant’Elmo, and the churches of the Cathedral, Santa Chiara, San Domenico Maggiore, San Lorenzo Maggiore, Santa Maria La Nova, San Paolo Maggiore and the Albergo dei Poveri, all of which suffered the greatest damages s a result of historical earthquakes (Figure 11). In detail, among the castles/fortresses of medieval age between the 11th and 13th centuries, Castel Sant’Elmo is the one that reported the greatest damage due to the earthquake of 1456, while Castel Capuano suffered the most significant damage from the earthquake of 1688. Moreover, Castel Capuano was the most affected by all of the historical earthquakes generally, as it suffered serious damages following the 1456, 1694 and 1805 earthquakes. Castel Nuovo (Maschio Angioino) was seriously damaged by the seismic events of 1688, 1694 and 1805.

Figure 11.

The graphs show the damage that the castles, historical buildings and churches suffered as a result of the historical earthquakes of the Southern Apennines.

Considering the damage suffered by the churches, we observed that the Duomo (13th century), Santa Chiara (14th century), San Domenico Maggiore (13th century), San Lorenzo Maggiore (13th century), Santa Maria La Nova (13th century) and San Paolo Maggiore (16th century) churches suffered damage from almost all of the strong earthquakes under consideration (Figure 11). The Church of San Paolo Maggiore suffered great damage following the earthquake of 1688 and minor damage following the earthquake of 1694. The historical monumental building of the Albergo dei Poveri, among the largest buildings in Europe (18th century), showed a different damage compared to the churches and castles/fortresses as it had severe damage only resulting from the 1805 earthquake, and partial collapses due to the 1980 seismic event.

Our study shows that the vulnerability of buildings repeatedly damaged by earthquakes depends on very complex factors that go beyond the magnitude of the earthquakes themselves, the distance from the epicenter and the condition of the building, but also the geological substrate on which they were built, which in some cases can amplify the shaking due to the earthquake [5,23,59,60].

From this perspective, the seismic history of the recent past teaches us that other major events could also occur in the future and affect the city of Naples and its historical heritage again. Therefore, the “prevention” and preservation of architectural heritage appears to be the correct solution, together with respect for the regulations surrounding the construction of buildings in seismic zones. Accordingly, it is necessary to think about the methods of intervention, especially to reduce the risk of damage and/or the collapse of historical and monumental buildings. Therefore, a collective effort involving interdisciplinary action could address administrations and demand that they take prompt actions in order to protect the historical center of Naples, which was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1995: “… considering that the site is of exceptional value. It is one of the most ancient cities in Europe, whose contemporary urban fabric preserves the elements of its long and eventful history. Its setting on the Bay of Naples gives it an outstanding universal value which has had a profound influence in many parts of Europe and beyond”.

5. Conclusions

The collected documentary and historical sources consulted has allowed us to evaluate the damage suffered by the historical buildings of Naples following the strongest historical earthquakes of the Apennines (Appendix A Table A1), and to perform the seismic macro-zoning of the ancient center of city (Figure 10). The damage level of the historical earthquakes of 5 December 1456, 5 June 1688 and 26 July 1805 have caused the highest level of damage (VIII on the MCS scale) in the historical center of city.

Moreover, we want to emphasize that the methodology used in this paper has allowed us to identify and classify the monumental buildings examined, a seismic history that has never been carried out by other authors. The same methodology can be extended and applied to other socio-cultural contexts globally [61].

The other result of significant scientific interest in this study is the density map of damages (Figure 10), which, for the first time, provides evidence of the areas of the historic center of Naples that are architecturally the most vulnerable to damage from strong earthquakes in the future (Figure 11). These data can be of fundamental importance for the construction of detailed maps of seismic microzonation by the technicians in charge (e.g., engineers, architects and geologists).

In conclusion, our study could be considered to contribute to the mitigation of seismic risk in the city of Naples [23,57,60], and provides useful advice on the protection of the historical heritage of Naples, whose historical center is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P. and G.G.; methodology, S.P.; software, R.N.; validation, R.N., G.A., G.G., E.S. and V.N.; formal analysis, G.G., S.P. and G.A.; investigation, G.G.; resources, R.N.; data curation, R.N. and G.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P., G.G., R.N. and G.A.; writing—review and editing, R.N., G.G. and G.A.; visualization, S.P. and E.S.; supervision, S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the two anonymous referees for their useful suggestions which helped us to improve the original manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The table contains the strong historical earthquakes of the Southern Apennines and the earthquakes of the Neapolitan volcanic areas that were affected in the city of Naples [1, 8, 9, 10, 12).

Table A1.

The table contains the strong historical earthquakes of the Southern Apennines and the earthquakes of the Neapolitan volcanic areas that were affected in the city of Naples [1, 8, 9, 10, 12).

| Date | Epicentral Area | I0 | Mw | I Naples | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1293 09 04 | Sannio-Matese | 8–9 | 5.80 | 7 | 1 |

| 1349 09 09 | Lazio-Molise | 10 | 6.80 | 7–8 | 1 |

| 1386 03 17 | Napoli | 7–8 | 3.75 | 7–8 | 1 |

| 1406 09 16 | Napoli | 5 | 3.12 | 5 | 1 |

| 1456 12 05 | Appennino centro-meridionale | 11 | 7.19 | 8 | 1 |

| 1456 12 30 08 20 | Appennino centro-meridionale | 7 | 1 | ||

| 1457 01 08 | Napoli | 6 | 3.37 | 6 | 1 |

| 1457 02 10 | Capua | 5–6 | 4.40 | 3 | 1 |

| 1466 01 15 02 25 | Irpinia-Basilicata | 8–9 | 5.98 | 5 | 1 |

| 1468 05 26 | Napoli | 4 | 4 | 10 | |

| 1470 01–1472 09 | Pozzuoli | 7 | 10 | ||

| 1475 08 11 | Napoli | 4–5 | 4–5 | 10 | |

| 1496 11 09 | Napoli | 4 | 4 | 10 | |

| 1498 10 07 | Campi Flegrei (Pozzuoli) | 5–6 | 3.25 | 5 | 1; 10 |

| 1498 10 19 | Campi Flegrei (Pozzuoli) | 5–6 | 5 | 10 | |

| 1498 10 20 | Campi Flegrei (Pozzuoli) | 7 | 3.63 | 3 | 1; 10 |

| 1499 03 18 00 45 | Napoli | 4–5 | 4–5 | 10 | |

| 1499 03 18 01 45 | Napoli | 5 | 3.12 | 5 | 1; 10 |

| 1505 05 18 08 55 | Campi Flegrei (Agnano) | 8 [5) | 3.75 | 6 | 1; 10 |

| 1508 01 25 15 20 | Napoli | 4–5 | 4–5 | 10 | |

| 1508 04 25 | Pozzuoli | 8 | 10 | ||

| 1508 07 19 08 55 | Napoli | 5 | 3.12 | 5 | 1; 10 |

| 1517 03 29 19 | Irpinia | 7–8 | 5.33 | 5 | 1 |

| 1520 01 28 23 50 | Campi Flegrei (Pozzuoli) | 6–7 | 3.50 | 5 | 1; 10 |

| 1536 08 07 | Napoli | 5 | 3.12 | 5 | 1; 10 |

| 1537 02 14 | Campi Flegrei (Pozzuoli) | 7–8 [5) | 3.50 | 4 | 1; 10 |

| 1538 04 20 | Napoli | 6 [5) | 3.25 | 6 | 1; 10 |

| 1538 09 20 | Campi Flegrei (Pozzuoli) | 5–6 | 3.25 | 4 | 1; 10 |

| 1538 09 22 | Campi Flegrei (Pozzuoli) | 5–6 | 3.25 | 4 | 1; 10 |

| 1538 09 23 | Campi Flegrei (Pozzuoli) | 5–6 | 3.25 | 4 | 1; 10 |

| 1538 09 24 | Campi Flegrei (Pozzuoli) | 5–6 | 3.25 | 4 | 1; 10 |

| 1538 09 25 | Campi Flegrei (Pozzuoli) | 5–6 | 3.25 | 4 | 1; 10 |

| 1538 09 26 | Campi Flegrei (Pozzuoli) | 5–6 | 3.25 | 4 | 1; 10 |

| 1538 09 27 | Campi Flegrei (Pozzuoli) | 5–6 | 3.25 | 4 | 1; 10 |

| 1538 09 28 06 00 | Campi Flegrei (Pozzuoli) | 5–6 | 3.25 | 4 | 1; 10 |

| 1538 09 28 17 30 | Campi Flegrei (Pozzuoli) | 5–6 | 3.25 | 4 | 1; 10 |

| 1538 09 29 11 00 | Campi Flegrei (Pozzuoli) | 5–6 | 3.25 | 4 | 1; 10 |

| 1538 09 29 18 30 (eruption) | Campi Flegrei (Pozzuoli) | 8 | 3.88 | 5 | 1; 10 |

| 1560 05 11 04 40 | Costa Pugliese centrale | 8 | 5.66 | 3 | 1 |

| 1561 07 31 20 10 | Penisola sorrentina | 8 | 5.56 | 7 | 1 |

| 1561 08 19 15 50 | Vallo di Diano | 10 | 6.72 | 4-5 | 1 |

| 1564 07 | Campi Flegrei | 4–5 (5) | 3.12 | 5–6 | 1; 10 |

| 1566 05 06 22 45 | Napoli | 5 | 3.12 | 5–6 [5) | 1; 10 |

| 1568 12 27 | Campi Flegrei (Pozzuoli) | 6 | 3.37 | 4-5 | 1; 10 |

| 1570 04 30 23 06 | Campi Flegrei (Pozzuoli) | 6–7 | 3.50 | 5 | 1; 10 |

| 1570 06 17 | Pozzuoli | 4–5 | 4 | 10 | |

| 1575 06 05 20 30 | Napoli | 5–6 | 3.25 | 6–7 | 1 |

| 1580 06 09 07 10 | Campi Flegrei (Pozzuoli) | 4–5 | 4 | 10 | |

| 1582 06 05 07 08 | Campi Flegrei (Pozzuoli) | 8 | 3.88 | 5 | 1; 10 |

| 1601 08 10 UT | Napoli | 5 | 3.12 | 5 | 1 |

| 1616 01 12 20 20 UT | Napoli | 5 | - | 5 | 8 |

| 1616 12 07/08 20 05 UT | Napoli | 5 | 5 | 8 | |

| 1620 03 20 UT | Napoli | 5 | 5 | 8 | |

| 1621 08 10 00 40 UT | Napoli | 5 | 5 | 8 | |

| 1622 02 25 05 40 UT | Napoli | 5 | 5 | 8 | |

| 1622 04 10 UT | Napoli | 5 | 5 | 8 | |

| 1622 11 06 18 55 UT | Napoli | 5 | 5 | 8 | |

| 1622 11 06 21 25UT | Napoli | 4 | 4 | 8 | |

| 1626 03 10 00 40 UT | Napoli | 6–7 | 6–7 | 8 | |

| 1626 03 10 22 15 UT | Napoli | 4 | 4 | 8 | |

| 1626 03 15 19 05 UT | Napoli | 4 | 4 | 8 | |

| 1626 03 22 05 15 UT | Napoli | 3 | 3 | 8 | |

| 1626 09 08 04 55 UT | Napoli | 3 | 3 | 8 | |

| 1626 10 21 13 45 UT | Napoli | 3 | 3 | 8 | |

| 1626 10 27 12 40 UT | Napoli | 3 | 3 | 8 | |

| 1626 11 02 23 15 UT | Napoli | 4 | 4 | 8 | |

| 1627 07 30 10 50 | Capitanata | 10 | 6.66 | 5 | 1 |

| 1630 04 02 06 50 UT | Napoli | 5 | 5 | 8 | |

| 1631 12 | Area Vesuviana | 5–6 | 3.25 | 5–6 | 1 |

| 1631 12 15 21UT | Area Vesuviana | 5–6 | 3 | 8 | |

| 1631 12 15 23UT | Area Vesuviana | 7 | 8 | ||

| 1631 12 17 | Area Vesuviana | 7 | 5.17 | 4 | |

| 1638 03 27 15 05 | Calabria centrale | 11 | 7.09 | 3 | 1 |

| 1646 05 31 | Gargano | 10 | 6.72 | 5 | 1 |

| 1657 01 29 02 | Capitanata | 8–9 | 5.96 | 4–5 | 1 |

| 1685 05 | Penisola Sorrentina | 5–6 | 4.73 | 5 | 1 |

| 1687 04 25 00 30 | Penisola Sorrentina | 6 | 4.63 | 5 | 1 |

| 1688 06 05 15 30 | Sannio | 11 | 7.06 | 8 | 1 |

| 1688 07 23 | Capitanata | 7–8 | 5.33 | 3 | 1 |

| 1688 08 14 | Beneventano | 6–7 | 4.86 | 3 | 1 |

| 1692 03 04 22 20 | Irpinia | 8 | 5.88 | 5 | 1 |

| 1694 09 08 11 40 | Irpinia-Basilicata | 10 | 6.73 | 7 | 1 |

| 1694 10 09 | Avellino | 5–6 | 4.40 | 3 | 1 |

| 1702 03 14 04 30 | Sannio-Irpinia | 6–7 | 4.86 | 5 | 1 |

| 1702 03 14 05 | Sannio-Irpinia | 10 | 6.56 | 6 | 1 |

| 1702 04 02 06 20 | Sannio-Irpinia | 6–7 | 4.86 | 4–5 | 1 |

| 1703 01 14 18 | Valnerina | 11 | 6.92 | 3–4 | 1 |

| 1703 01 16 13 30 | Appennino laziale-abruzzese | 3 | 1 | ||

| 1703 02 02 11 05 | Aquilano | 10 | 6.67 | 3 | 1 |

| 1706 11 03 13 | Maiella | 10–11 | 6.84 | 4–5 | 1 |

| 1720 08 28 | Cassinese | 5-6 | 4.35 | 5 | 1 |

| 1731 03 20 03 | Tavoliere delle Puglie | 9 | 6.33 | 5 | 1 |

| 1731 10 17 11 | Tavoliere delle Puglie | 6–7 | 4.86 | 4–5 | 1 |

| 1732 11 29 07 40 | Irpinia | 10–11 | 6.75 | 7 | 1 |

| 1733 05 15 00 30 | Puglia | 3 | 1 | ||

| 1735 01 26 | Casertano | 5 | 4.16 | 3–4 | 1 |

| 1737 03 31 17 20 | Monti di Avella | 7 | 5.10 | 4 | 1 |

| 1739 02 12 21 30 | Tavoliere delle Puglie | 5–6 | 4.40 | 3 | 1 |

| 1739 02 27 04 20 | Benevento | 5–6 | 4.40 | 4 | 1 |

| 1741 08 06 13 30 | Irpinia | 7–8 | 5.44 | 4 | 1 |

| 1742 08 17 | Napoli | 5–6 | 3.25 | 5–6 | 1 |

| 1743 02 20 | Ionio settentrionale | 9 | 6.68 | 4–5 | 1 |

| 1756 10 22 14 | Napoletano | 6–7 | 3.50 | 6–7 | 1 |

| 1760 12 23 | Area vesuviana | 6–7 | 3.50 | 4–5 | 1 |

| 1777 06 06 16 15 | Tirreno meridionale | 4–5 | 1 | ||

| 1779 10 01 00 45 | Napoletano | 6 | 3.37 | 4 | 1 |

| 1779 12 12 | Napoletano | 6 | 3.37 | 3 | 1 |

| 1783 03 28 18 55 | Calabria centrale | 11 | 7.03 | 4 | 1 |

| 1794 06 12 22 30 | Irpinia | 7 | 5.26 | 5 | 1 |

| 1794 06 15 | Area vesuviana | 4 | 2.87 | 3 | 1 |

| 1805 07 26 21 | Molise | 10 | 6.68 | 7–8 | 1 |

| 1805 10 13 22 | Pianura Campana | 7 | 5.10 | 3 | 1 |

| 1806 08 26 07 35 | Colli Albani | 8 | 5.61 | 3–4 | 1 |

| 1814 11 25 | Beneventano | 5–6 | 4.40 | 3 | 1 |

| 1817 04 17 | Potentino | 4–5 | 3.97 | 3 | 1 |

| 1821 11 22 01 15 | Costa molisana | 7–8 | 5.59 | 3 | 1 |

| 1826 02 01 16 | Potentino | 8 | 5.74 | 3 | 1 |

| 1826 10 26 18 | Salento | 6–7 | 5.22 | 3 | 1 |

| 1832 03 08 18 30 | Crotonese | 10 | 6.65 | 3 | 1 |

| 1836 04 25 00 20 | Calabria settentrionale | 9 | 6.18 | 3–4 | 1 |

| 1836 11 20 07 30 | Appennino lucano | 8 | 5.86 | 5 | 1 |

| 1841 02 21 | Gargano | 6–7 | 5.17 | 3 | 1 |

| 1846 08 08 | Potentino | 6–7 | 5.18 | 3 | 1 |

| 1851 08 14 13 20 | Vulture | 10 | 6.52 | 5 | 1 |

| 1851 08 14 14 40 | Vulture | 7–8 | 5.48 | 3–4 | 1 |

| 1853 04 09 12 45 | Irpinia | 8 | 5.60 | 4 | 1 |

| 1857 12 16 21 15 | Basilicata | 11 | 7.12 | 6 | 1 |

| 1858 03 07 14 | Campania meridionale | 7–8 | 5.39 | 3 | 1 |

| 1858 05 24 09 20 | Tavoliere delle Puglie | 4–5 | 4.35 | 3 | 1 |

| 1861 12 09 | Torre del Greco | 5–6 | 3.25 | 3 | 1 |

| 1870 10 04 16 55 | Cosentino | 9–10 | 6.24 | 3 | 1 |

| 1874 12 06 15 50 | Val Comino | 7–8 | 5.48 | 4 | 1 |

| 1875 12 06 | Gargano | 8 | 5.86 | 6–7 | 1 |

| 1881 09 10 07 | Chietino | 7–8 | 5.41 | 3 | 1 |

| 1882 06 06 05 40 | Isernino | 7 | 5.20 | 5 | 1 |

| 1883 07 28 20 25 | Isola d’Ischia | 9–10 | 4.26 | 5 | 1 |

| 1893 01 25 | Vallo di Diano | 7 | 5.15 | 3–4 | 1 |

| 1895 02 01 07 24 3 | Monti del Partenio | 5 | 4.29 | 3–4 | 1 |

| 1895 08 09 17 38 2 | Adriatico centrale | 6 | 5.11 | 3 | 1 |

| 1901 07 31 10 38 3 | Sorano | 7 | 5.16 | 3–4 | 1 |

| 1903 05 04 03 44 | Valle Caudina | 7 | 4.69 | 3 | 1 |

| 1903 12 07 05 58 | Beneventano | 4–5 | 4.14 | 3 | 1 |

| 1905 03 14 19 16 | Avellinese | 6–7 | 4.90 | 4–5 | 1 |

| 1905 08 25 20 41 | Valle Peligna | 6 | 5.15 | 3 | 1 |

| 1905 09 08 01 43 | Calabria centrale | 10–11 | 6.95 | 3–4 | 1 |

| 1905 11 26 | Irpinia | 7–8 | 5.18 | 3–4 | 1 |

| 1907 12 18 19 21 | Monti Picentini | 5–6 | 4.52 | 3 | 1 |

| 1908 12 28 04 20 2 | Stretto di Messina | 11 | 7.10 | 3 | 1 |

| 1910 06 07 02 04 | Irpinia-Basilicata | 8 | 5.76 | 4 | 1 |

| 1913 10 04 18 26 | Molise | 7–8 | 5.35 | 4 | 1 |

| 1915 01 13 06 52 4 | Marsica | 11 | 7.08 | 5 | 1 |

| 1922 12 29 12 22 0 | Val Roveto | 6–7 | 5.24 | 3 | 1 |

| 1923 11 08 12 28 | Appennino campano-lucano | 6 | 4.73 | 3 | 1 |

| 1924 03 26 20 50 | Sannio | 4 | 4.06 | 3 | 1 |

| 1924 05 09 05 48 | Irpinia | 4 | 4.71 | 3–4 | 1 |

| 1927 05 25 02 50 | Sannio | 6 | 4.98 | 4 | 1 |

| 1930 04 27 01 46 | Salernitano | 7 | 4.98 | 4 | 1 |

| 1930 07 23 00 08 | Irpinia | 10 | 6.67 | 7 | 1 |

| 1930 10 30 07 13 | Senigallia | 8 | 5.83 | 3 | 1 |

| 936 04 03 18 42 | Valle Caudina | 5–6 | 4.25 | 3 | 1 |

| 1948 08 18 21 12 2 | Gargano | 7–8 | 5.55 | 3 | 1 |

| 1962 08 21 18 19 | Irpinia | 9 | 6.15 | 6–7 | 1 |

| 1971 05 06 03 45 0 | Irpinia | 6 | 4.83 | 4 | 1 |

| 1973 08 08 14 36 2 | Appennino campano-lucano | 5–6 | 4.75 | 3 | 1 |

| 1975 06 19 10 11 | Gargano | 6 | 5.02 | 4 | 1 |

| 1979 09 19 21 35 3 | Valnerina | 8–9 | 5.83 | 4 | 1 |

| 1980 06 14 20 56 5 | Marsica | 5–6 | 4.96 | 3 | 1 |

| 1980 11 23 18 34 5 | Irpinia-Basilicata | 10 | 6.81 | 7 | 1 |

| 1980 12 03 23 54 2 | Irpinia-Basilicata | 6 | 4.83 | 4 | 1 |

| 1981 01 09 00 12 4 | Irpinia-Basilicata | 5–6 | 4.36 | 3–4 | 1 |

| 1981 02 14 17 27 4 | Monti di Avella | 7–8 | 4.88 | 5–6 | 1 |

| 1982 03 21 09 44 0 | Golfo di Policastro | 7–8 | 5.23 | 4 | 1 |

| 1983 10 04 08 09 | Campi Flegrei | 6 | 4.0 | 5–6 | 9 |

| 1984 05 07 17 50 | Monti della Meta | 8 | 5.86 | 5–6 | 1 |

| 1996 04 03 13 04 3 | Irpinia | 6 | 4.90 | 3 | 1 |

| 1999 10 09 05 41 0 | Area vesuviana | 5 | 3.24 | 4 | 1 |

| 2002 11 01 15 09 0 | Molise | 7 | 5.72 | 3–4 | 1 |

Table A2.

The historical buildings of Naples damaged by the earthquake of 1456 [5,42]. MD = Minor Damage; SD = Serious Damage; GD = Great Damage.

Table A2.

The historical buildings of Naples damaged by the earthquake of 1456 [5,42]. MD = Minor Damage; SD = Serious Damage; GD = Great Damage.

| Original Name | Type of Building | Age of Building (Century) | Damages | Long. Lat. (UTM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Certosa di San Martino | Church/Monastery | 14th | SD | 4521651 436027 |

| Duomo/Vescovado | Cathedral | 13th | GD | 4522649 437588 |

| Sant’ Agostino alla Zecca | Church | 13th | GD | 4522283 437870 |

| Sant’ Agrippino a Forcella | Church | 13th | GD | 4522431 437800 |

| Sant’Anna dei Lombardi/Santa Maria di Monteoliveto | Monastery | 15th | SD | 4521801 436820 |

| Santissima Annunziata Maggiore a Forcella | Church | 13th rebuilt 16th and 18th | MD | 4522498 438049 |

| Santa Chiara | Church/Monastery | 14th | GD | 4521985 437035 |

| San Domenico Maggiore | Church | 13th | SD | 4522232 437151 |

| San Giovanni Maggiore | Church | 4th rebuilt in 6th | SD | 4521869 437242 |

| San Lorenzo Maggiore | Church | 13th | SD | 4522474 437466 |

| Santa Maria del Carmine Maggiore | Church/Monastery | 12th | SD | 4522010 438260 |

| Santa Maria Maggiore alla Pietrasanta | Church | 17th | SD | 4522415 437148 |

| Santa Maria La Nova | 13th | MD | 4521684 437042 | |

| San Pietro Martire | Church | 13th | SD | 4521789 437434 |

| Santi Severino e Sossio | Church /Monastery | 10th | SD | 4522122 437478 |

| Castel Capuano | Fortress Castle | 12th | SD | 4522729 437980 |

| Castel Sant’Elmo | Fortress Castle | 14th | GD | 4521698 435848 |

Table A3.

The historical buildings of Naples damaged by the 1688 earthquake [5,6,7,14]; MD = Minor Damage; SD = Serious Damage; GD = Great Damage.

Table A3.

The historical buildings of Naples damaged by the 1688 earthquake [5,6,7,14]; MD = Minor Damage; SD = Serious Damage; GD = Great Damage.

| Original Name | Type of Building | Age of Building (Century) | Damages | Long./Lat. (UTM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Certosa di San Martino | Church | 14th | MD | 4521651 436027 |

| Croce di Lucca | 16th | SD | 4522364 437090 | |

| Gesù Nuovo (ex palazzo Sanseverino di Salerno) | Church | 16th | GD | 4522111 436931 |

| Gesù Vecchio | Church | 16th rebuilt in 17th | SD | 4522009 437369 |

| Madonna della Pietà/Madonna della Pietà dei Turchini | Church | 16th | MD | 4521402 436995 |

| Sant’Agostino degli Scalzi/Santa Maria della Verità/ | Church | 17th | GD | 4522994 436593 |

| Santissima Annunziata Maggiore a Forcella | Church | 13 rebuilt in 16th and 18th | MD | 4522498 438049 |

| Sant’Antonio delle Monache a Port’alba | Church | 16th | MD | 4522421 436973 |

| Santissimi Apostoli | 5th | MD | 4522875 437657 | |

| Santa Chiara | Church | 14th | SD | 4521985 437035 |

| San Diego all’Ospedaletto/Spedaletto/San Giuseppe Maggiore/ | Church/Monastery | 16th | MD | 4521526 437022 |

| San Domenico Maggiore | Church | 13th | GD | 4522232 437151 |

| San Filippo e Giacomo | Church | 16th | MD | 4522245 437383 |

| San Gaudioso | Church | 8th demolished in 20th | GD | 4522654 437097 |

| San Giorgio Maggiore | Church | 4th–5th rebuilt after 17th | MD | 4522332 437677 |

| San Gregorio Armeno/S. Liguoro | Church | 8th rebuilt in 16th | SD | 4522390 437425 |

| San Lorenzo Maggiore | Church | 13th | GD | 4522474 437466 |

| Santa Maria del Carmine Maggiore | Church/Monastery | 12th rebuilt in 13th | GD | 4522010 438260 |

| Santa Maria Donnalbina | Church | 9th rebuilt 17th | MD | 4521772 436991 |

| Santa Maria Maggiore alla Pietrasanta | 6th rebuilt in 17th | GD | 4522415 437148 | |

| Santa Maria ai Monti/Santa Maria ai Monti dei Pii Operari (Capodimonte) | Church | 17th | SD | 4525595 438190 |

| Santa Maria della Sanità/San Vincenzo | Church | 17th | MD | 4523452 436700 |

| Santa Maria del Soccorso all’Arenella | Church | 17th | SD | 4522767 435228 |

| San Nicola alla Carità | Church | 17th | MD | 4521870 436689 |

| San Paolo Maggiore | Church | 16th | GD | 4522531 437358 |

| Santi Severino and Sossio/San Severino dei Benedettini | Church | 10th | MD | 4522122 437478 |

| San Severo al Pendino | Church | 16th | MD | 4522275 437666 |

| Santa Teresa degli Scalzi | Church | 17th | MD | 4522916 436713 |

| San Tomaso d’Aquino | Church | 16th demolished in 20th | MD | 4522328 436988 |

| Castel Sant’Elmo | Fortress Castle | 14th | SD | 4521698 435848 |

| Castel Capuano | Fortress Castle | 12th | GD | 4522729 437980 |

| Castel Nuovo (Maschio Angioino) | Fortress Castle | 13th | SD | 4521087 436995 |

| Palazzo reale | Palace | 17th | 4520844 436731 | |

| Torrione del Carmine | Fortress | 14th rebuilt in16th | SD | 4521932 438341 |

Table A4.

The historical buildings of Naples damaged by the 1694 earthquake [2,43]. MD = Minor Damage; SD = Serious Damage; GD = Great Damage.

Table A4.

The historical buildings of Naples damaged by the 1694 earthquake [2,43]. MD = Minor Damage; SD = Serious Damage; GD = Great Damage.

| Original Name | Type of Building | Age of Building (Century) | Damages | Long., Lat. (UTM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Certosa di San Martino | Church | 14th | SD | 4521651 436027 |

| Croce di Lucca | Church | 16th | MD | 4522364 437090 |

| Duomo Vescovado | Cathedral | 13th | MD | 4522649 437588 |

| Gesù e Maria | Church/Monastery | 16th | MD | 4522553 436290 |

| Gesù Nuovo (ex palazzo Sanseverino di Salerno | Church | 16th | SD | 4522111 436931 |

| Girolamini/San Filippo Neri | Church | 16th | SD | 4522585 437498 |

| Sant’Agostino degli Scalzi/Santa Maria della Verità | Church | 17th | MD | 4522994 436593 |

| Santissima Annunziata Maggiore a Forcella | Church | 13th rebuilt in 16th and 18th | MD | 4522498 438049 |

| Sant’Antonio delle Monache a Port’Alba | Church | 16th | MD | 4522421 436973 |

| Santa Chiara | Church | 14th | MD | 4521985 437035 |

| San Domenico Maggiore | Church | 13th | MD | 4522232 437151 |

| San Gaudioso | Church | 8th demolished in 20th | SD | 4523476 436706 |

| San Giovanni a Carbonara | Church/Monastery | 14th | MD | 4523037 437661 |

| San Giovanni a Mare | Church | 12th | MD | 4521981 437896 |

| San Gregorio Armeno/San Liguoro | Church | 16th | MD | 4522390 437425 |

| Santa Maria del Carmine Maggiore | Church/Monastery | 12th | SD | 4522010 438260 |

| Santa Maria Donnaregina vecchia | Church | 14th | MD | 4522873 437498 |

| Santa Maria Maddalena dei Pazzi | Church | 17th | SD | 4522697 436312 |

| Santa Maria Maggiore alla Pietrasanta | Church | 6th rebuilt in 17th | SD | 4522415 437148 |

| Santa Maria la Nova | Church | 13th | SD | 4521684 437042 |

| Santa Maria della Pace | Church | 16th | MD | 4522624 437788 |

| Santa Maria della Sanità | Church /Monastery | XVII | MD | 4523452 436700 |

| San Michele Arcangelo | Church | 17th rebuilt in 18th | SD | 4522188 436759 |

| San Paolo Maggiore | Church | 16th | MD | 4522531 437358 |

| Santi Severino e Sossio | Church | 10th | SD | 4522122 437478 |

| Santa Teresa degli Scalzi | Church/Monastery | 17th | MD | 4522916 436713 |

| Castel Capuano | Fortress/Castle | 12th | SD | 4522729 437980 |

| Castel Nuovo (Maschio Angioino) | Fortress/Castle | 13th | SD | 4521087 436995 |

| Regio Arsenale | Fortress | 16th destroyed in the early 20th | SD | 4520755 436908 |

| Casamatta a Porta Nolana | Building | 16th | GD | 4522395 438291 |

| Palazzo Carafa d’Andria | Palace | 15th | SD | 4522105 437447 |

| Palazzo Carafa di Maddaloni | Palace | 16th | SD | 4521980 436753 |

| Palazzo Pignatelli di Monteleone | Palace | 16th | SD | 4522003 436881 |

| Presidio di Pizzofalcone (Caserma Nino Bixio) | Palace | 17th | MD | 4520342 436470 |

Table A5.

The historical buildings of Naples damaged by the 1805 earthquake [1,5,6,7,44,4549,50]. MD = Minor Damage; SD = Serious Damage; GD = Great Damage.

Table A5.

The historical buildings of Naples damaged by the 1805 earthquake [1,5,6,7,44,4549,50]. MD = Minor Damage; SD = Serious Damage; GD = Great Damage.

| Original Name | Building | Age of Building (Century) | Damages | Long., Lat. (UTM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Certosa di San Martino | Church/Monastery | 14th | SD | 4521651 436027 |

| Croce di Lucca | 16th | SD | 4522364 437090 | |

| Divino Amore | Church | 18th | SD | 4522306 437609 |

| Duomo (Vescovado) | Church | 13th | SD | 4522649 437588 |

| Gesù e Maria | Church/Monastery | 16th | MD | 4522553 436290 |

| Gesù vecchio | 16 threbuilt in 17th | SD | 4522009 437369 | |

| Girolamini o San Filippo Neri | 16th | SD | 4522585 437498 | |

| Sant’Agnello Maggiore | Church/Monastery | 9th | SD | 4522738 437000 |

| Sant’Agostino alla Zecca o Sant’Agostino Maggiore | Church/Monastery | 13th rebuilt after 1456 earthquake | SD | 4522283 437870 |

| Sant’ Agrippino a Forcella | 13th | SD | 4522431 437800 | |

| Sant’Anna dei Lombardi/Monteoliveto | Church/Monastery | 15th | SD | 4521801 436820 |

| Sant’Anna di Palazzo/San Rosario di Palazzo | Church/Monastery | 16th | MD | |

| Santissimi Apostoli | Church | 5th | SD | 4522875 437657 |

| Santa Brigida a Toledo | Church/Monastery | 17th | SD | 4521152 436699 |

| San Carlo alle Mortelle | Church/Monastery | 17th | MD | 4521123 436034 |

| Santa Caterina di Siena | Church/Monastery | 16th | SD | 4521177 436169 |

| Santa Chiara | Church/Monastery | 14th | SD | 4521985 437035 |

| San Demetrio e Bonifacio ai Banchi nuovi | Church | 18th | SD | 4521808 437163 |

| San Domenico Maggiore | Church/Monastery | 13th | SD | 4522232 437151 |

| Sant’Efremo nuovo | Church/Monastery | 17th | SD | 4522809 436357 |

| San Francesco delle Monache | Church | 14th | SD | |

| San Geronimo delle Monache | Church | 15th | SD | 4522064 437241 |

| San Giovanni Maggiore | Church | 4th rebuilt in 6th | MD | 4521869 437242 |

| San Luigi a Palazzo | Church/Monastery | MD | 4520747 436555 | |

| Santa Maria degli Angeli a Pizzofalcone | Church/Monastery | 16 threbuilt in 17th | MD | 4520751 436311 |

| Santa Maria Apparente | Church | 16th | MD | 4521269 435796 |

| Santa Maria del Carmine Maggiore | Church/Monastery | 12th | SD | 4522010 438260 |

| Santa Maria Donnalbina | Church/Monastery | 9th rebuilt in 17th | SD | 4521772 436991 |

| Santa Maria Donnaregina vecchia | Church/ | 14th | SD | 4522873 437498 |

| Santa Maria Egiziaca a Pizzofalcone | Church/Monastery | 17th | SD | 4520617 436504 |

| Santa Maria delle Grazie (Monastero dei Teatini di Santa Maria delle Grazie a Toledo) | Church/Monastery | 17th | SD | 4521564 436669 |

| Santa Maria Maddalena dei Pazzi e del SS. Sacramento | Church/Monastery | 17th | MD | 4522697 436312 |

| Santa Maria della Mercede a Montecalvario dell’Ordine Francescano | Church | 16th | SD | 4521557 436418 |

| Santa Maria la Nova | Church/Monastery | 13th | SD | 4521684 437042 |

| Santa Maria della Sapienza; | Church/Monastery | 17th | SD | 4522492 436956 |

| Santa Maria della Solitaria | Church/Monastery | 16th demolished in 19th | MD | 4520622 436612 |

| Santa Maria della Vittoria | Church/Monastery | 16th | SD | 4520482 436077 |

| San Paolo Maggiore | Church/Monastery | 16th | SD | 4522531 437358 |

| San Pietro ad Aram | Church | 12th rebuilt in 17th | SD | 4522511 438192 |

| San Potito | Church/Monastery | 17th | MD | 4522600 436728 |

| San Severo fuori le mura (Conventuali a Capodimonte) | Church | 16th | SD | 4523579 436923 |

| Santissimo Spirito dei padri Verginiani | Church/Monastery | 16th | SD | 4522055 436698 |

| San Tommaso d’Aquino | Church/Monastery | 16th demolished in 20th | SD | 4522328 436988 |

| Castel Capuano | Fortress/Castle | 12th | SD | 4522729 437980 |

| Castel Nuovo (Maschio Angioino) | Fortress /Castle | 13th | SD | 4521087 436995 |

| Castel dell’Ovo | Fortress/Castle | 12th | SD | 4519963 436531 |

| Albergo dei Poveri | Palace | 18th | SD | 4523860 438097 |

| Collegio militare dell’ Annunziatella | Palace | 16th | MD | 4520452 436290 |

| Reggia di Capodimonte | Palace | 18th | MD | 4524258 436839 |

| Palazzo Cellammare/Francavilla | Palace H | 16th | SD | 4520834 436108 |

| Palazzo del Duca della Regina | Palace | 15th | SD | 4522234 437286 |

| Palazzo dei Granili | Palace | 18th | SD | 4521587 439667 |

| Palazzo Salluzzo di Corigliano | Palace | 16th | GD | 4522210 437225 |

| Palazzo del Principe d’Angri (Palazzo Doria d’Angri) | Palace | 18th | SD | 4522029 436745 |

| Palazzo dei Principi di Roccella (Carafa di Roccella) | Palace | 17th | SD | 4520935 435668 |

| Palazzo Reale | Palace | 17th | MD | 4520844 436731 |

| Palazzo dei Regi studi (Museo Archeologico Nazionale) | Palace | 16th | SD | 4522751 436825 |

| Palazzo de Sangro di Sansevero | Palace | 16th | SD | 4522252 437179 |

| Ponte della Maddalena | Bridge | 16th | SD | 4523495 436666 |

Table A6.

The historical buildings of Naples damaged by the 1980 earthquake [5,6,7,14,56,57,58] and the estimated level of damage. (GD Great damage; SD Serious damage; MD Minor damage).

Table A6.

The historical buildings of Naples damaged by the 1980 earthquake [5,6,7,14,56,57,58] and the estimated level of damage. (GD Great damage; SD Serious damage; MD Minor damage).

| Original Name | Type of Building | Age of Building (Century) | Damages | Long., Lat. (UTM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cappella Sansevero/chiesa di Santa Maria della Pietà | 16th- | MD | 4522283 437191 | |

| Compagnia della Disciplina della Croce | Church | 13th | SD | 4522328 437891 |

| Divino Amore/San Camillo | Church | 17th | SD | 4522306 437609 |

| Duomo/Vescovado | Church | 13th | SD | 4522649 437588 |

| Eremo dei Camaldoli | Church | 16th | MD | 4523330 431905 |

| Gesù e Maria | Church | 16th | SD | 4522553 436290 |

| Gesù delle Monache | Church/Monastry | 16th | SD | 4522891 437330 |

| Gesù Nuovo | Church | 16th | MD | 4522111 436931 |

| Girolamini | Church/Monastry | 16th | SD | 4522585 437498 |

| Monte di Pietà | Church | 16th | MD | 4522249 437430 |

| Nunziatella/Santissima Annunziata | Church | 16th | MD | 4520482 436315 |

| Padri della Missione Vincenziani | Church | 17th | MD | 4523166 437203 |

| Pio Monte della Misericordia | Church | 17th | MD | 4522577 437661 |

| Regina Paradisi ai Guantai ai Camaldoli | Church | 19th | MD | 4524483 431849 |

| Sant’Agostino degli Scalzi/Santa Maria della Verità | Church | 17th | SD | 4522994 436593 |

| Sant’Agostino alla Zecca o Maggiore | Church | 13th rebuilt after 1456 earthquake | SD | 4522283 437870 |

| Sant’Anna dei Lombardi/Santa Maria di Monteoliveto | Church | 15th | SD | 4521801 436820 |

| Sant’Anna di Palazzo/San Rosario di Palazzo | Church | 16th | SD | 4521076 436432 |

| Santissima Annunziata Maggiore a Forcella | Church | 13th rebuilt in 16th and 18th | SD | 4522498 438049 |

| Sant’Antonio Abate | Church | 13th | MD | 4523619 438068 |

| Santi Antonio e Alfonso a Tarsia | Church | 16th | MD | 4522261 436453 |

| Santissimi Apostoli | Church | 5th | SD | 4522875 437657 |

| Sant’Aspreno ai Crociferi | Church | 17th | SD | 4523076 437293 |

| San Biagio Maggiore | Church | 17th | MD | 4522311 437484 |

| Santa Caterina a Chiaia | Church | 17th | MD | 4520730 436096 |

| Santa Caterina a Forniello | Church | 16th | SD | 4522860 438026 |

| Santa Chiara | Church | 14th | MD | 4521985 437035 |

| San Demetrio e Bonifacio ai Banchi Nuovi | Church | 18th | SD | 4521808 437163 |

| San Diego all’Ospedaletto o San Giuseppe Maggiore | Church | 16th | MD | 4521526 437022 |

| San Domenico Maggiore | Church | 13th | MD | 4522232 437151 |

| San Domenico Soriano | Church | 17th | SD | 4522281 436745 |

| Santi Filippo e Giacomo | Church | 16th | SD | 4522245 437383 |

| San Gennaro al Vomero | Church | 19th | SD | 4521828 435199 |

| Santa Geltrude | Church | 20th | MD | 4522668 436411 |

| San Giorgio Maggiore | Church | 4th–5th rebuilt after 17th | SD | 4522332 437677 |

| San Giovanni a Carbonara | Church | 14th | SD | 4523037 437661 |

| San Giovanni dei Fiorentini al Vomero | Church | 20th | MD | 4522253 434946 |

| San Giovanni del Sovrano Ordine di Malta o (Santi Bernardo e Margherita) Chiesa dell’Ordine di Malta | Church | 17th–18th | MD | 4522698 436527 |

| San Giuseppe dei Nudi | Church | 17th | MD | 4522690 436613 |

| San Giuseppe dei Vecchi | Church | 17th | MD | 4522587 436500 |

| San Gregorio Armeno | Church | 16th | MD | 4522390 437425 |

| San Lorenzo Maggiore | Church | 13th | SD | 4522474 437466 |

| Santi Marcellino e Festo | Church | Monasterys 7th–8th Church 17th | MD | 4522047 437495 |

| Santa Maria degli Angeli alle Croci | Church | 16th | MD | 4523651 437646 |

| Santa Maria degli Angeli a Pizzofalcone | Church | 16th rebuilt in 17th | MD | 4520751 436311 |

| Santa Maria delle Anime del Purgatorio ad Arco | Church | 17th | MD | 4522436 437262 |

| Santa Maria Avvocata | Church | 16th | MD | 4522410 436664 |

| Santa Maria di Caravaggio | Church | 17th | MD | 4522384 436750 |

| Santa Maria del Carmine Maggiore | Church | 12th | SD | 4522010 438260 |

| Santa Maria della Consolazione (centro storico ) | Church | 16th | MD | 4522854 437270 |

| Santa Maria Donnalbina | Church | 9th rebuilt in 17th | SD | 4521772 436991 |

| Santa Maria Donnaregina nuova | Church | 17th | MD | 4522814 437517 |

| Santa Maria Donnaregina vecchia | Church | 14th | MD | 4522873 437498 |

| Santa Maria Egiziaca a Forcella | Church | 14th | SD | 4522326 437984 |

| Santa Maria Egiziaca a Pizzofalcone | Church | 17th | MD | 4520617 436504 |

| Santa Maria delle Grazie (Monastero dei Teatini di Santa Maria delle Grazie a Toledo) | Church | 17th | MD | 4521564 436669 |

| Santa Maria Incoronata | Church | 14th | MD | 4521399 436946 |

| Santa Maria dei Miracoli | Church | 17th | MD | 4523352 437314 |

| Santa Maria di Montesanto | Church | 17th | MD | 4522124 436398 |

| Santa Maria ai Monti | Church | 17th | GD | 4525595 438190 |

| Santa Maria la Nova | Church | 13th | SD | 4521684 437042 |

| Santa Maria Ognibene | Church | 17th | MD | 4521739 436399 |

| Santa Maria della Pazienza alla Cesarea | Church | 17th | MD | 4522529 436051 |

| Santa Maria a Piazza | Church | 4th | MD | 4522456 437805 |

| Santa Maria del Popolo agli Incurabili | Church | 16th | SD | 4522817 437193 |

| Santa Maria della Provvidenza alla Salute | Church | 18th | SD | 4522921 435893 |

| Santa Maria Regina Coeli | Church | 16th | SD | 4522617 437143 |

| Santa Maria della Sanità | Church | 17th | MD | 4523452 436700 |

| Santa Maria della Stella | Church | 16th | SD | 4523025 436926 |

| San Nicola alla Carità | Church | 17th | MD | 4521870 436689 |

| San Nicola al Nilo | Church | 17th | MD | 4522270 437350 |

| San Nicola di Tolentino | Church | 17th | MD | 4521302 436069 |

| San Paolo Maggiore | Church | 16th | MD | 4522531 437358 |

| San Pasquale a Chiaia | Church | 18th | MD | 4520645 435593 |

| San Pietro ad Aram | Church | 12th rebuilt in 17th | SD | 4522511 438192 |

| San Pietro a Maiella | Church | 13th | SD | 4522321 437031 |

| San Pietro Martire | Church | 13th | SD | 4521789 437434 |

| San Potito | Church | 17th | MD | 4522600 436728 |

| San Raffaele a Materdei | Church | 18th | MD | 4522953 436280 |

| Santa Maria del Rosario alle Pigne/ Rosariello | Church | 17th | SD | 4522925 437068 |

| Santi Severino e Sossio | Church | 10th | SD | 4522122 437478 |

| San Severo fuori le mura a Capodimonte | Church | 16th | MD | 4523579 436923 |

| Santa Teresa dei Carmelitani Scalzi | Church | 17th | SD | 4522916 436713 |

| Santissima Trinità dei Pellegrini | Church | 16th | SD | 4522105 436564 |

| Castel Nuovo (Maschio Angioino) | Fortress Castle | 13th | MD | 4521087 436995 |

| Torre dei Franchi (Soccavo) | Tower | 15th | SD | 4522682 432058 |

| Albergo dei poveri | Palace | 18th | GD | 4523860 438097 |

| Archivio di Stato (Monastero Santi Severino e Sossio) | Palace | 10th | MD | 4522192 437563 |

| Biblioteca Nazionale Vittorio Emanuele III nel Palazzo Reale | Palace | 17th | MD | 4520844 436731 |

| Biblioteca dei Padri Passionisti | Palace | 17th | MD | 4525622 438181 |

| Biblioteca Universitaria (Casa del Salvatore) | Palace | 16th | MD | 4522057 437371 |

| Museo Archeologico Nazionale (Palazzo dei Regi studi) | Palace | 16th | GD | 4522751 436825 |

| Museo Civico Filangieri (Palazzo Como) | Palace | 15th | MD | 4522248 437683 |

| Museo Diego Aragona Pignatelli Cortez (Villa Pignatelli, Riviera di Chiaia) | Palace | 19th | SD | 4520712 435375 |

| Museo Nazionale di San Martino (Certosa di San Martino) | Palace | 14th | SD | 4521620 435988 |

| Palazzo del Principe d’Angri (Palazzo Doria d’Angri) | Palace | 17th | MD | 4522029 436745 |

| Palazzo Cellamare/Francavilla | Palace | 16th | MD | 4520834 436108 |

| Palazzo Sangro di Sansevero | Palace | 16th | SD | 4522283 437191 |

| Palazzo Spinelli di Laurino | Palace | 15th | MD | 4522385 437250 |

| Pinacoteca del Pio Monte della Misericordia | Palace | 17th | MD | 4522577 437661 |

| Villa Patrizi | Palace | 17th | MD | 4520765 433504 |

References

- Locati, M.; Camassi, R.; Rovida, A.; Ercolani, E.; Bernardini, F.; Castelli, V.; Caracciolo, C.H.; Tertulliani, A.; Rossi, A.; Azzaro, R.; et al. DBMI15, the 2015 Version of the Italian Macroseismic Database; Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia: Roma, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidoboni, E.; Ferrari, G.; Mariotti, D.; Comastri, A.; Tarabusi, G.; Sgattoni, G.; Valensise, G. CFTI5Med, Catalogue of Strong Earthquakes in Italy (461 B.C.-1997) and Mediterranean Area (760 B.C.-1500); Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV): Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postpischl, D. Catalogo dei terremoti italiani dall’anno 1000 al 1980; Ed. Quaderni della ricerca Scientifica: Bologna, Italy, 1985; 240p. [Google Scholar]

- Postpischl, D. (Ed.) Atlas of Isoseismal Maps of Italian Earthquakes; Quaderni Della Ricerca Scientifica: Roma, Italy, 1985; 164p. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, E.; Porfido, S.; Luongo, G.; Petrazzuoli, S.M. Damage Scenarios Induced by the Major Seismic Events from XV to XIX Century in Naples City with Particular Reference to the Seismic Response. In Proceedings of the Earthquake Engineering, Tenth World Conference, Madrid, Spain, 19–24 July 1992; Balkema: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1992; pp. 1075–1080. [Google Scholar]

- Porfido, S.; Alessio, G.; Gaudiosi, G.; Nappi, R.; Spiga, E. Analisi dei risentimenti dei forti terremoti appenninici che hanno colpito Napoli. In Grandi Opere di Art Studio Paparo; Ed. Studio Paparo: Napoli, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Porfido, S.; Alessio, G.; Gaudiosi, G.; Nappi, R.; Spiga, E. Centri storici ed hazard sismico: Il caso della città di Napoli. In Proceedings of the Conferenza Nazionale ASITA 2017, Salerno, Italy, 21–23 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Guidoboni, E.; Mariotti, D. Vesuvius: Earthquakes from 1600 up to the 1631 eruption. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2011, 200, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branno, A.; Esposito, E.G.I.; Luongo, G.; Marturano, A.; Porfido, S.; Rinaldis, V. The 4th October 1983—Magnitude 4 earthquake in Phlegraean Fields: Macroseismic survey. Bull. Volcanol. 1984, 47, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]