Reversible Hydrogen Storage Using Nanocomposites

Abstract

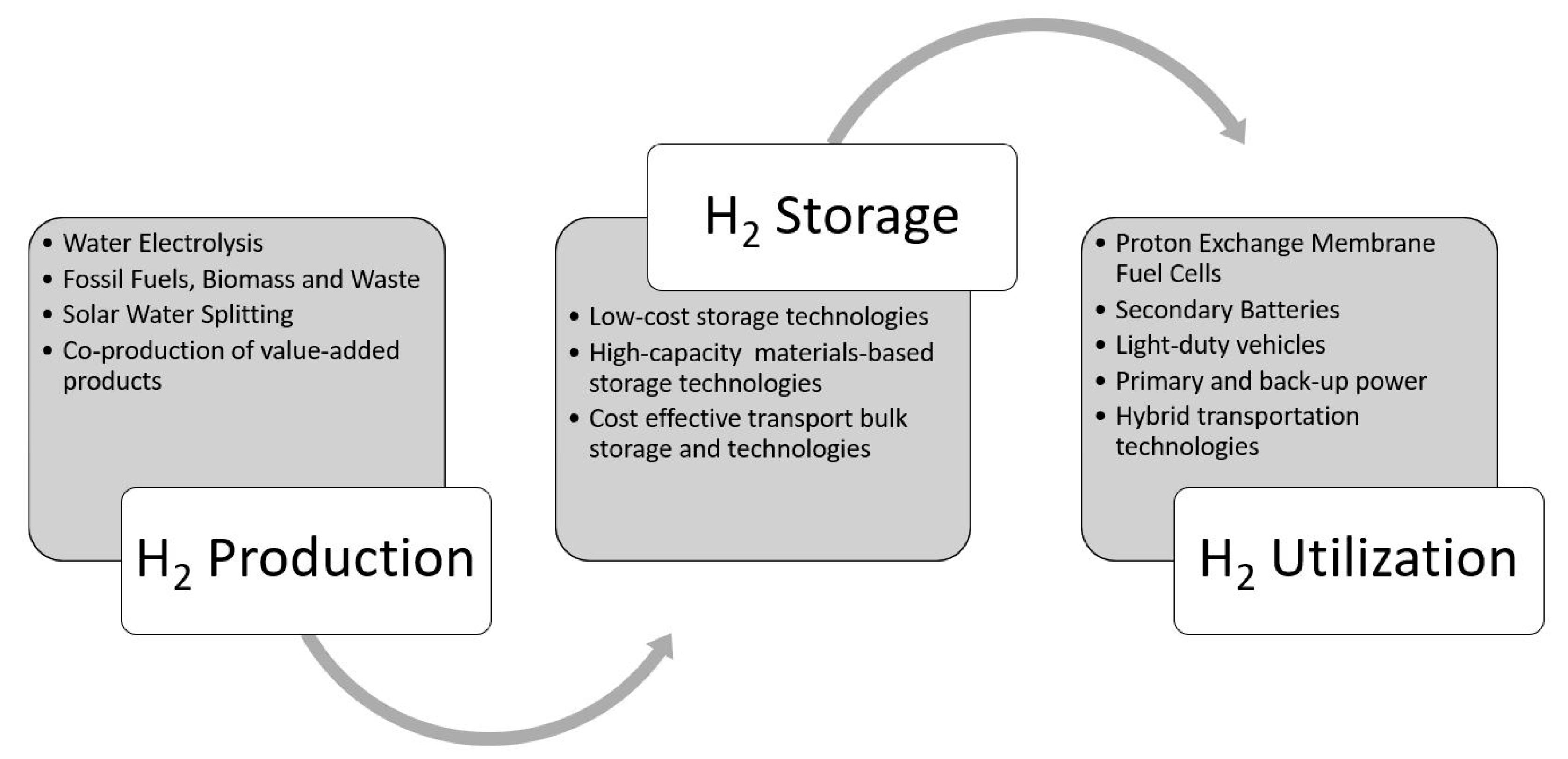

1. Introduction

2. Nanocomposite Materials for Hydrogen Storage

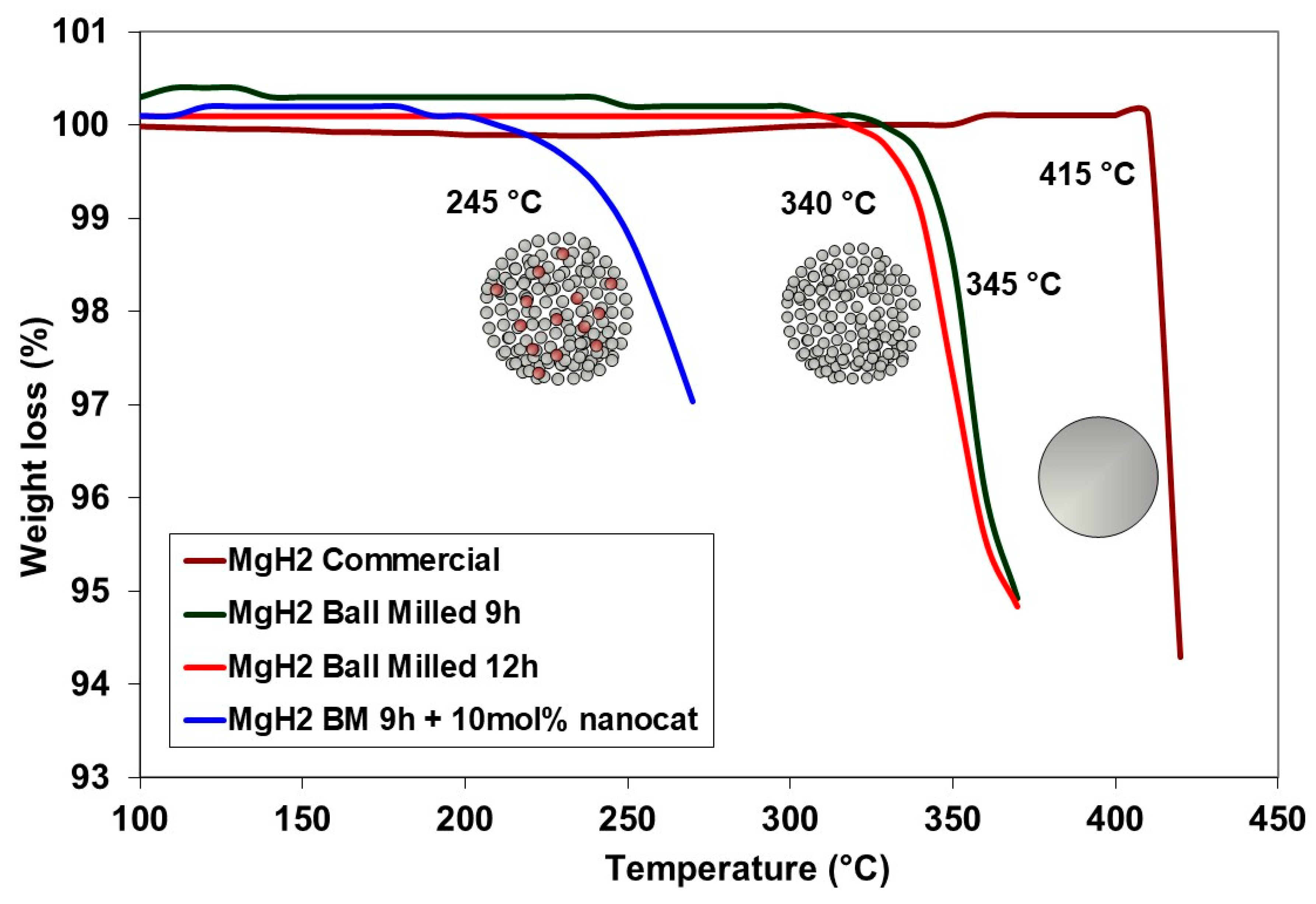

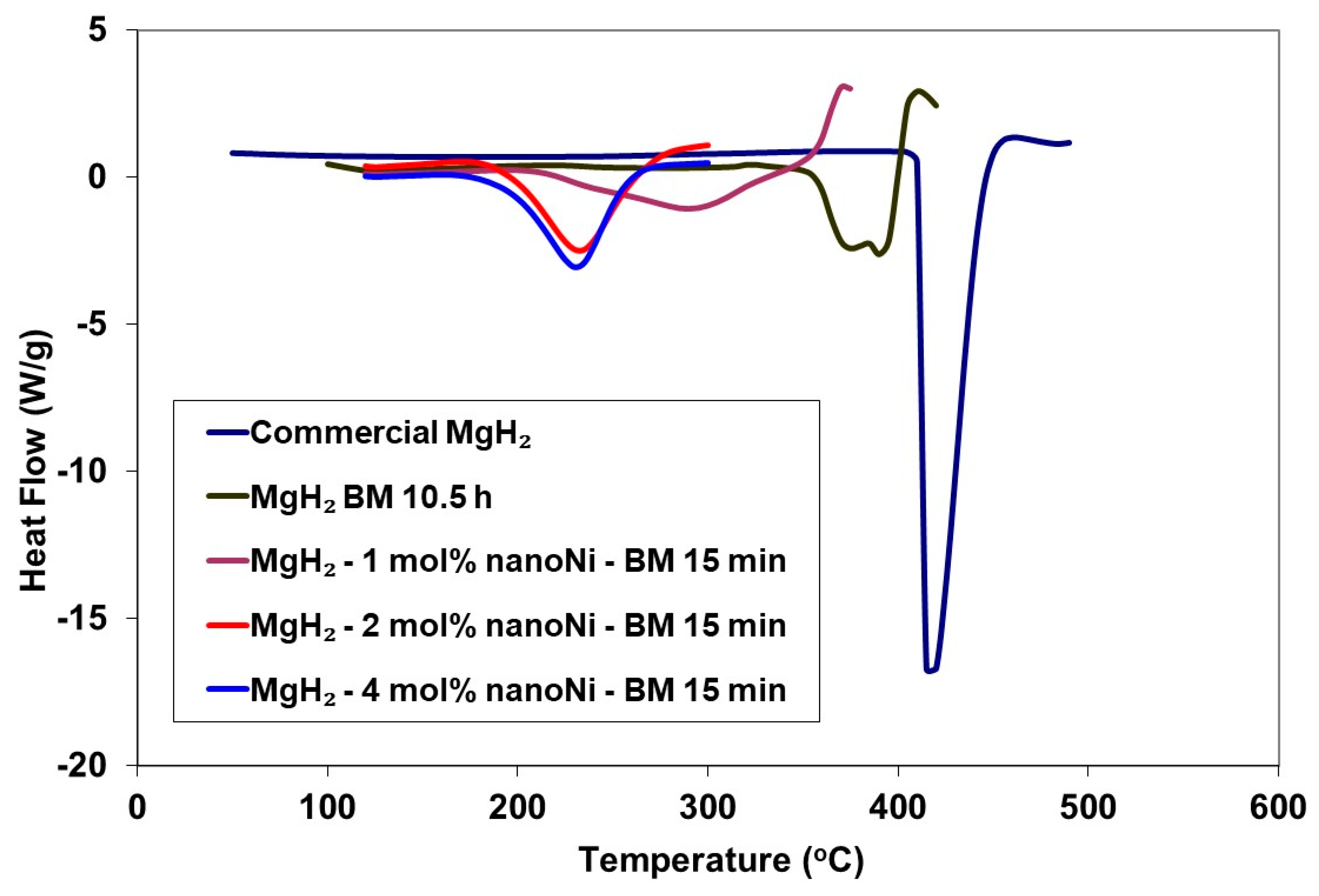

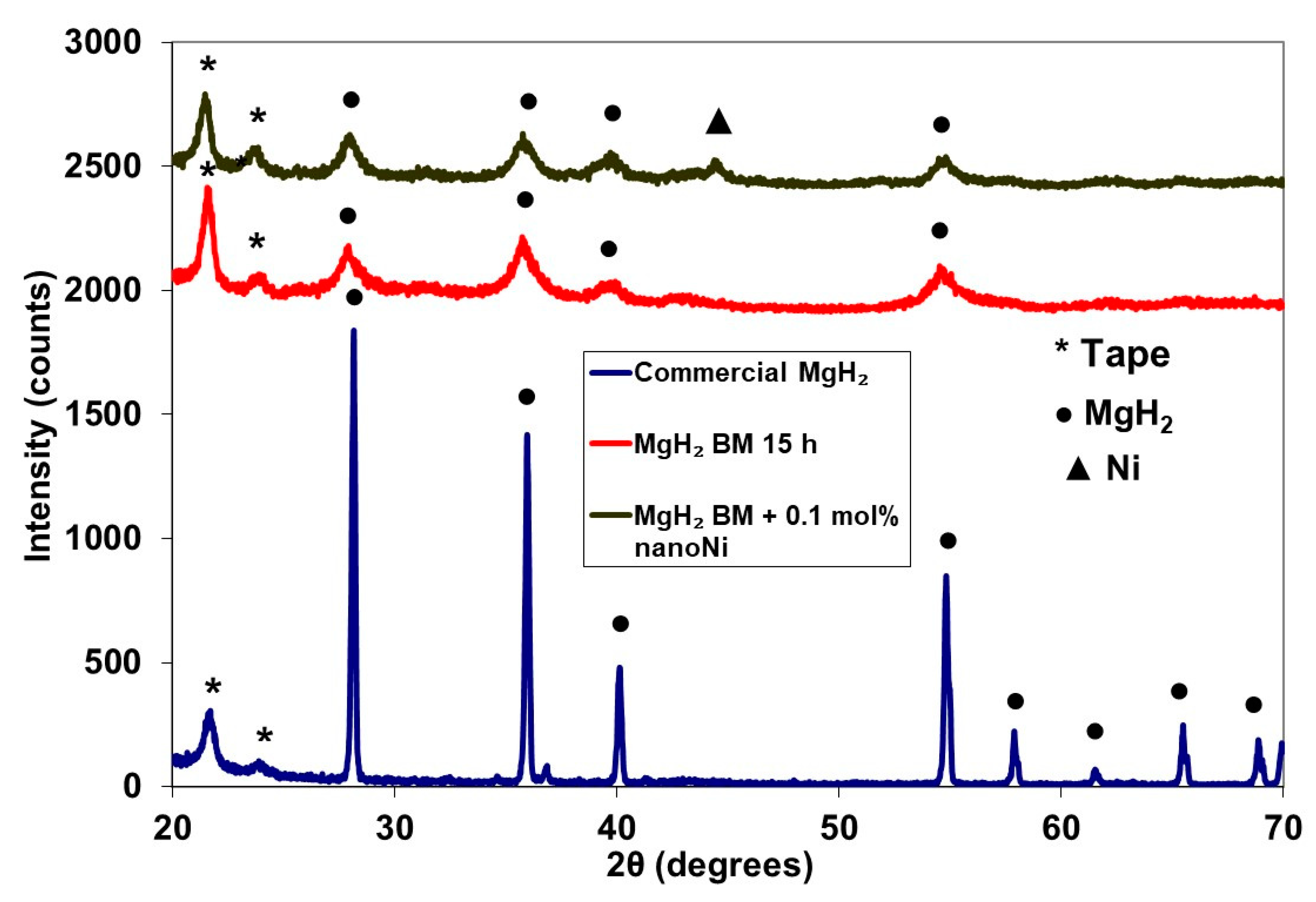

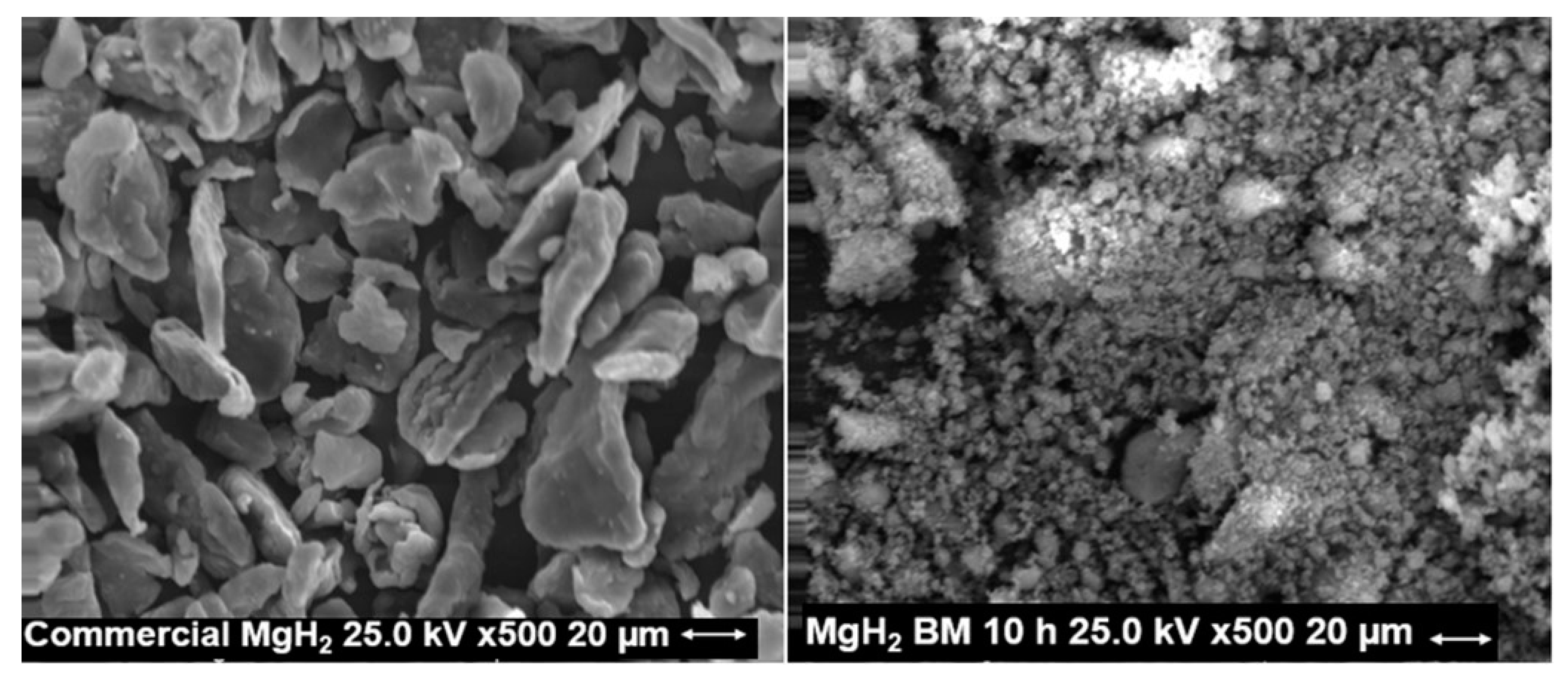

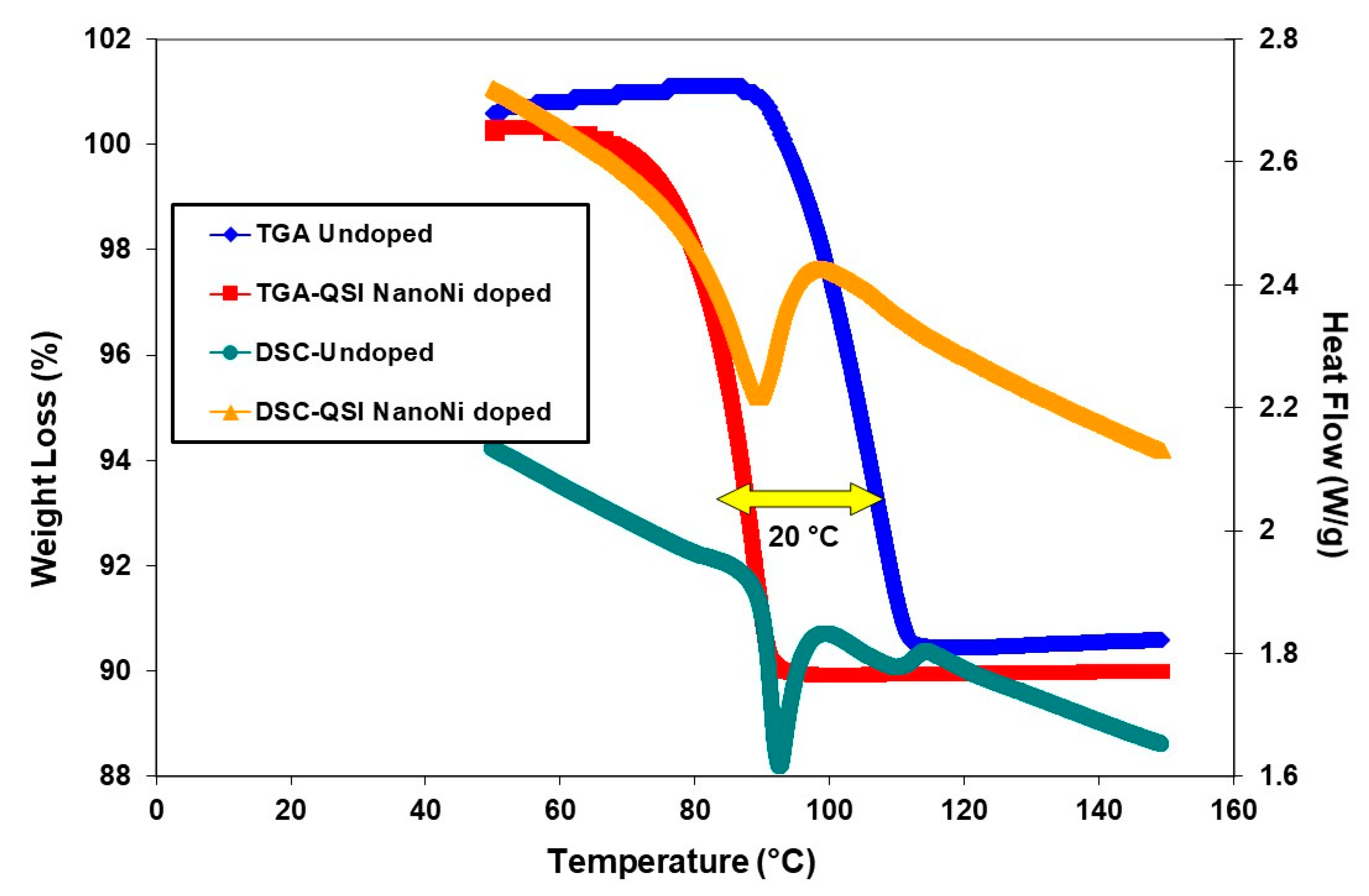

2.1. MgH2

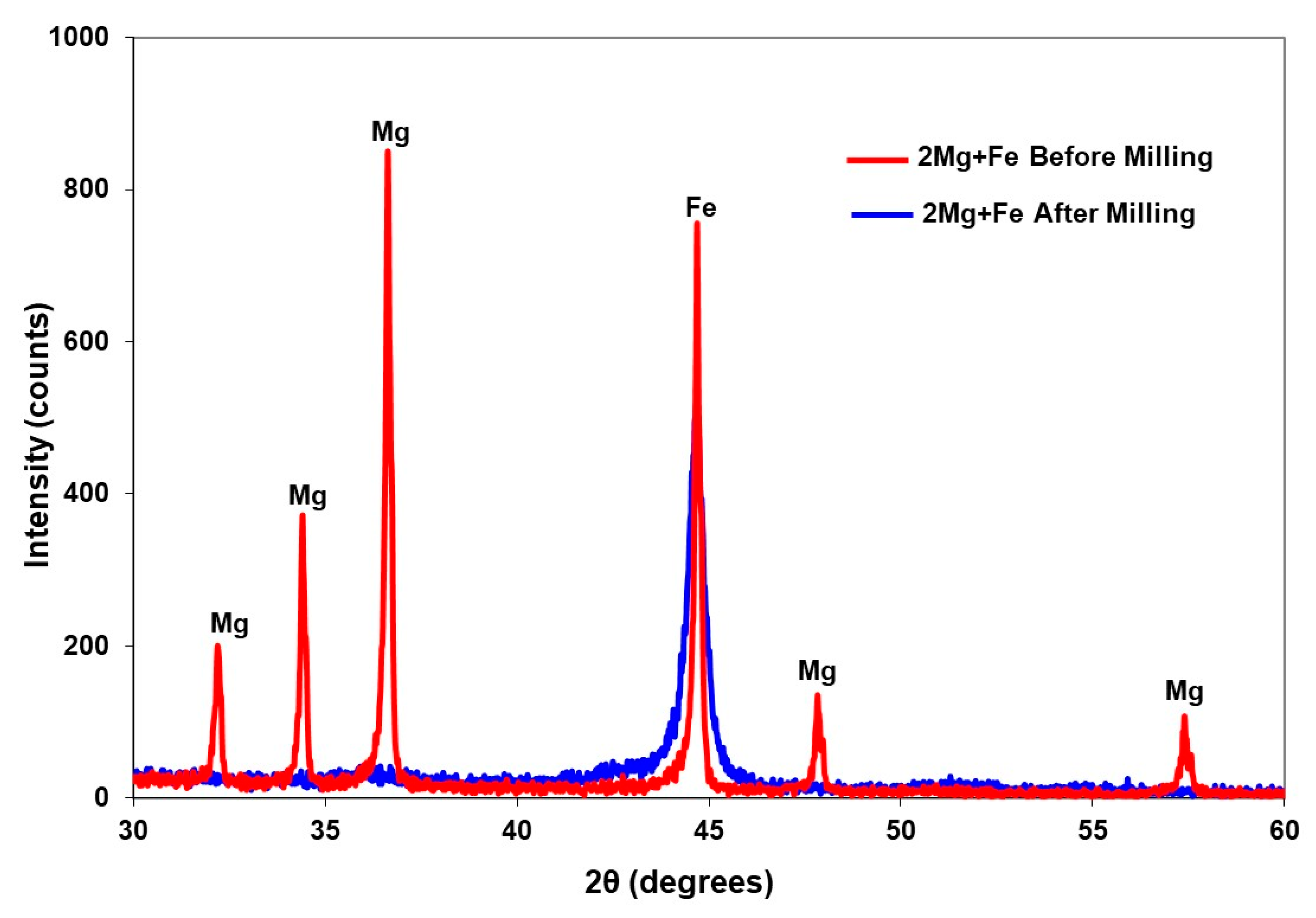

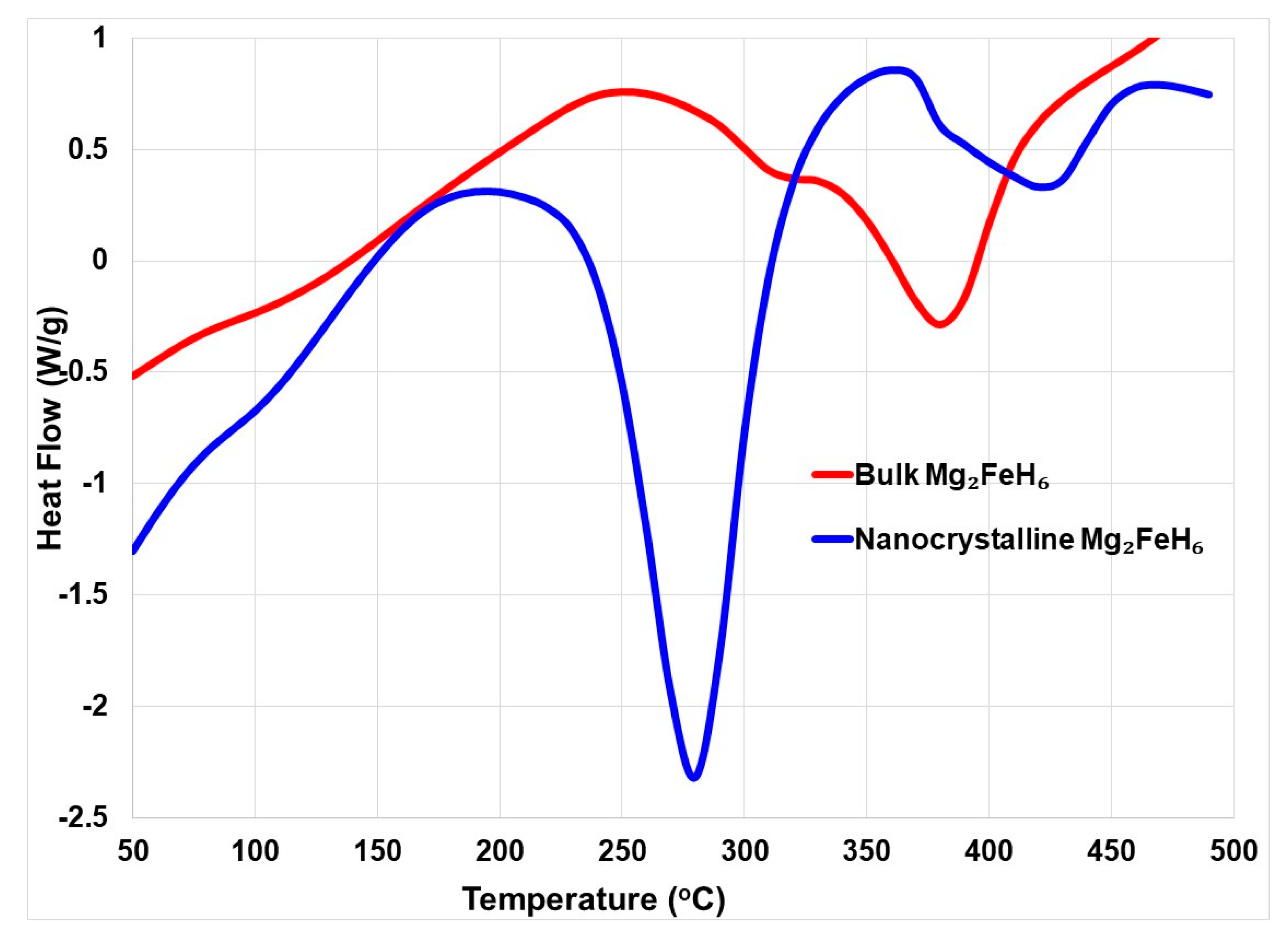

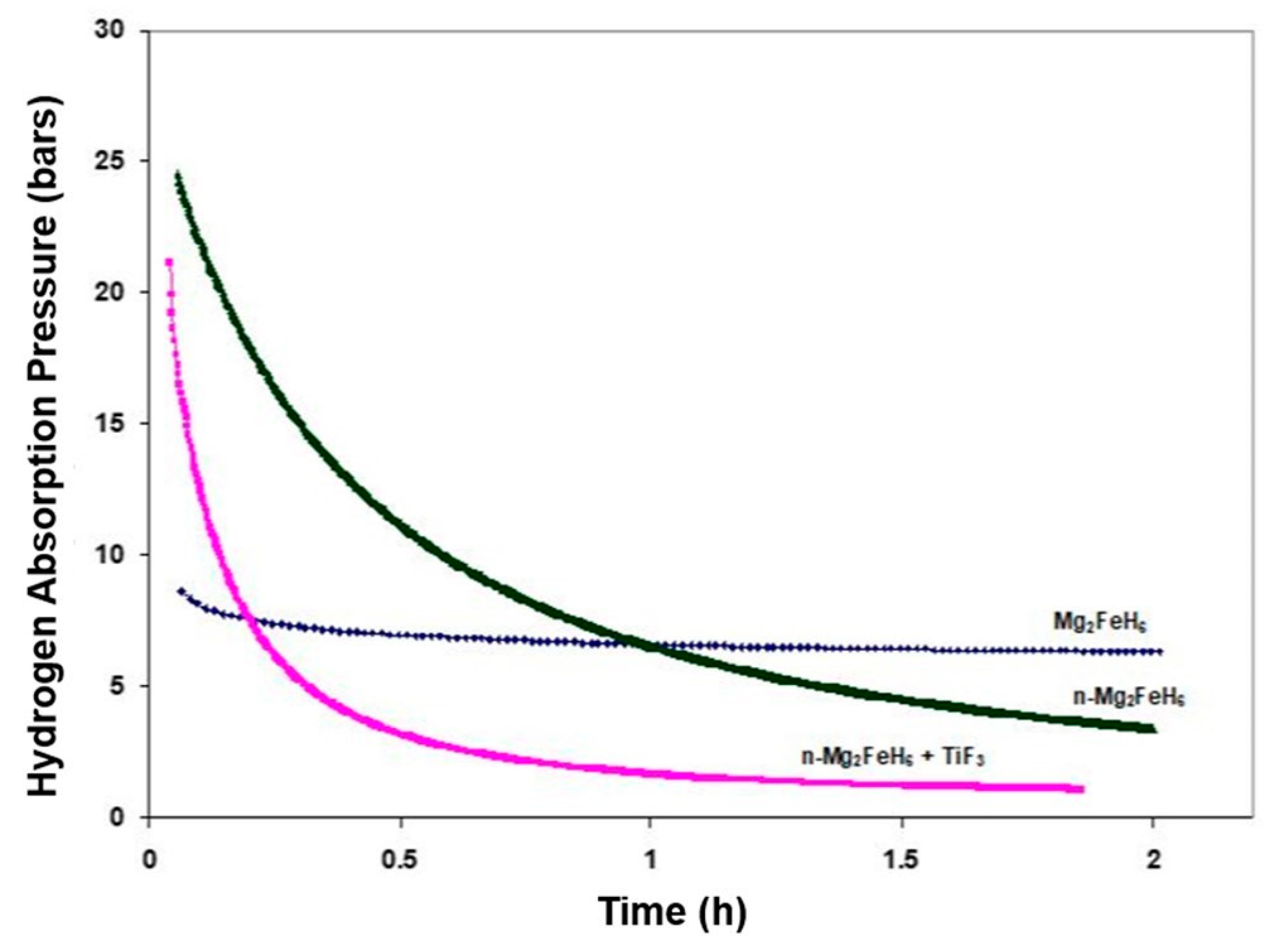

2.2. Mg2FeH6 Complex Hydride

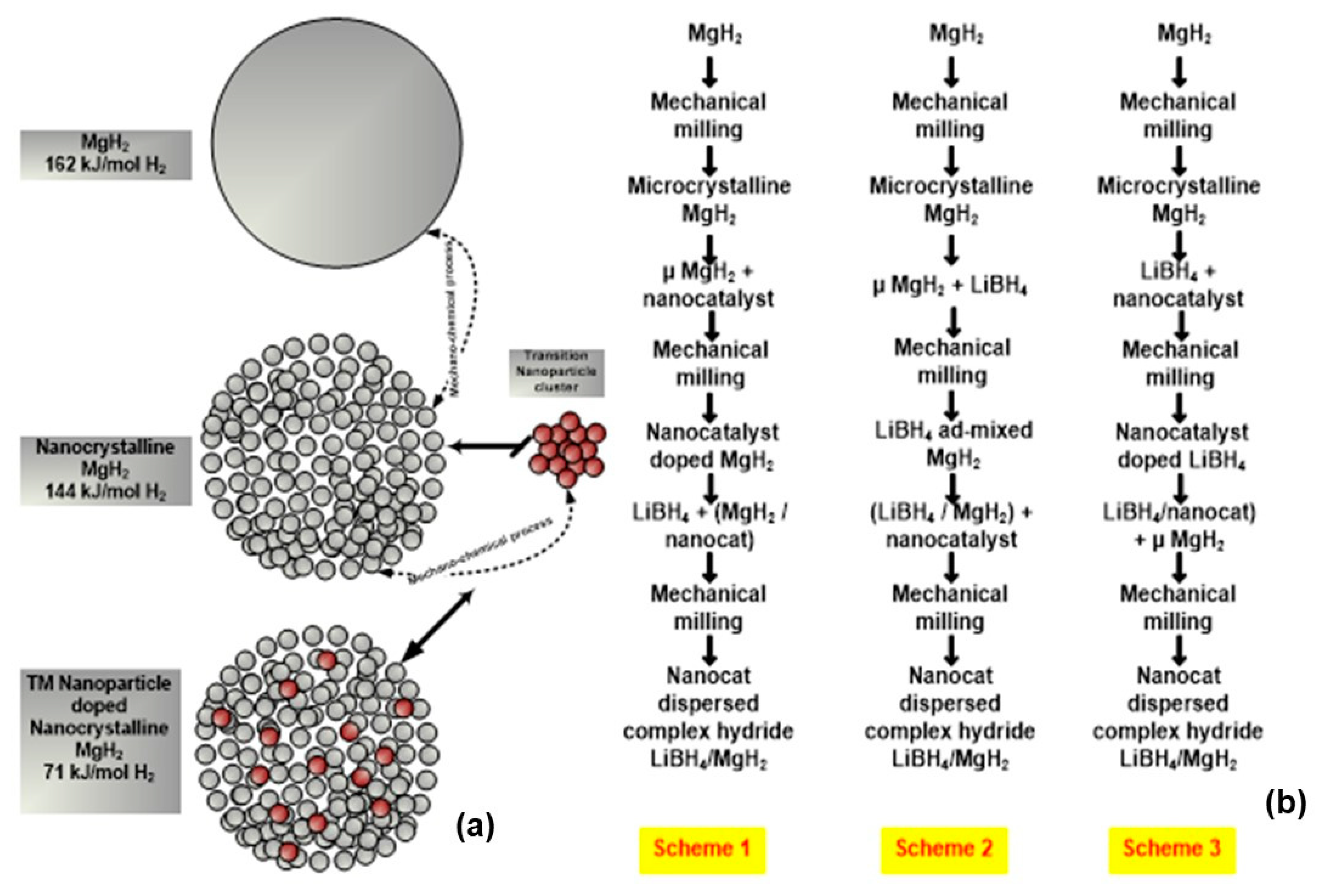

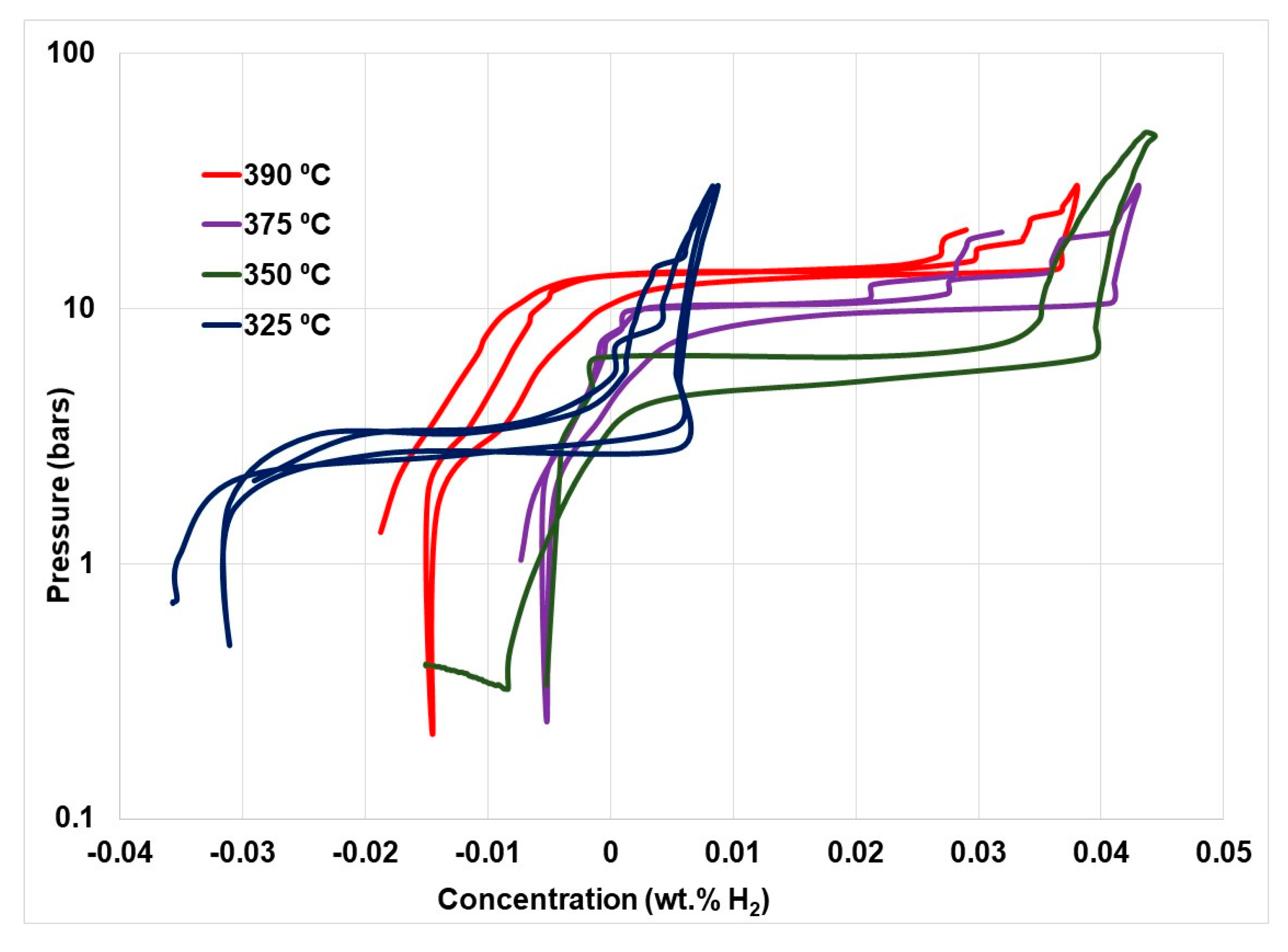

2.3. Nanoengineered Complex Hydrides (LiBH4/MgH2)

2.4. Nanocatalyst Doping in Complex Borohydrides

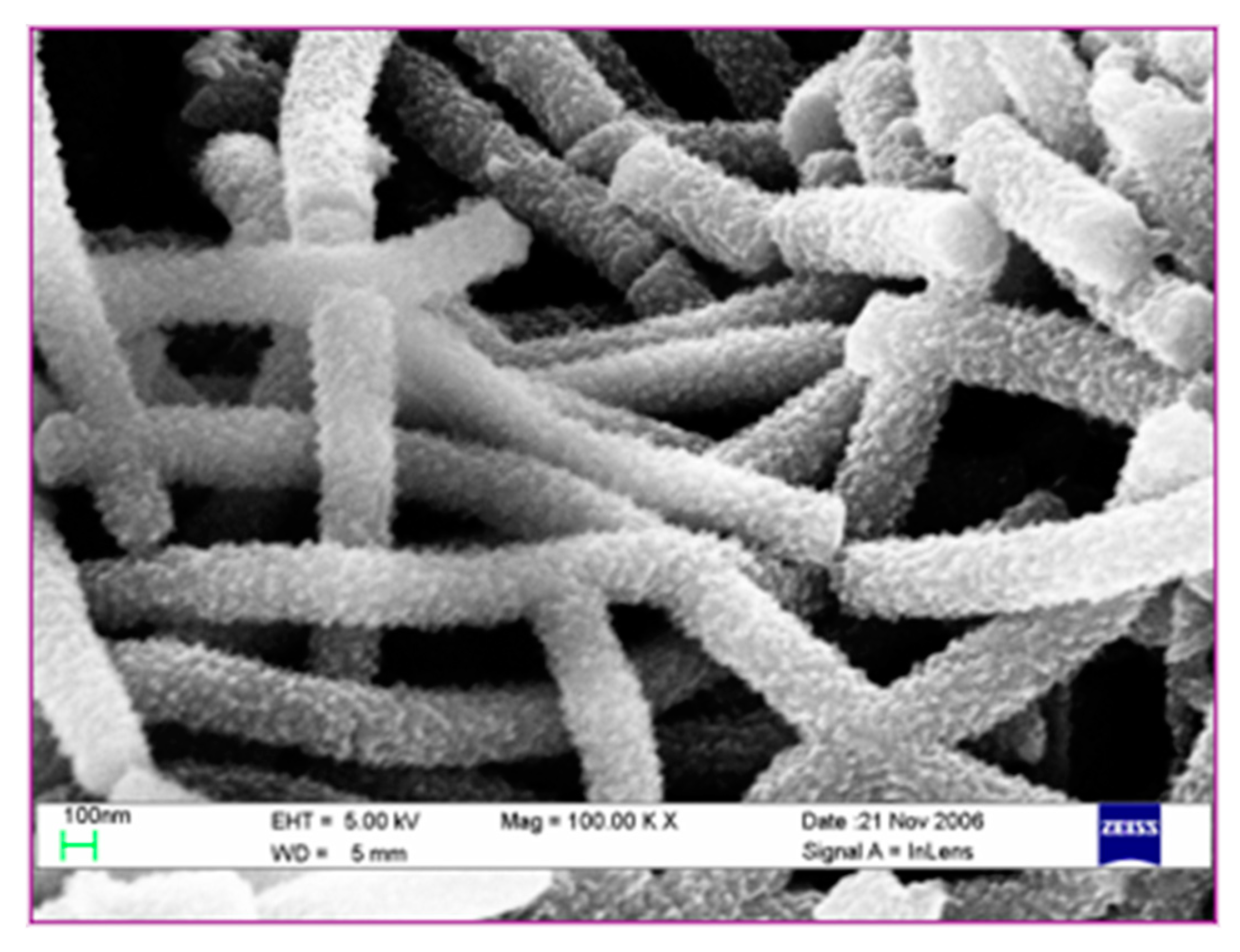

2.5. Carbon based Nanovariants

2.6. Polymeric Nanostructures

2.7. Metal Organic Frameworks (MOF)

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Satyapal, S.; Petrovic, J.; Thomas, G. Gassing up with hydrogen. Sci. Am. 2007, 296, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresselhaus, M.S.; Thomas, I.L. Alternative energy technologies. Nature 2001, 414, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richard, A.K. A Worrying Trend of Less Ice, Higher Seas. Science 2006, 311, 1698. [Google Scholar]

- David, L.G.; Janet, L.H.; Jia, L. Have we run out of fuel yet? Oil peaking analysis from an optimist’s perspective. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 515. [Google Scholar]

- Sakintuna, B.; Lamari-Darkrim, F.; Hirscher, M. Metal hydride materials for solid hydrogen storage: A review. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2007, 32, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.M.; Steeper, R.R.; Lutz, A.E. The Hydrogen-Fueled Internal Combustion Engine: A Technical Review. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2006, 31, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanakos, E.K.; Goswami, D.Y.; Srinivasan, S.S.; Wolan, J. Hydrogen Energy. In Environmentally Conscious Alternative Energy Production; Kutz, M., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; Volume 4, p. 165. [Google Scholar]

- Sherif, S.A.; Barbir, F.; Veziroglu, T.N.; Mahishi, M.; Srinivasan, S.S. Hydrogen Energy Technologies. In Handbook of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy; Kreith, F., Goswami, D.Y., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Granovskii, M.; Dincer, I.; Rosen, M.A. Economic and environmental comparison of conventional, hybrid, electric and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles. J. Power Sources 2006, 159, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontes, E.; Nilsson, E. Modeling the Fuel Cell. Ind. Phys. 2001, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.H.; Thomas, G.J. (Eds.) Materials for the Hydrogen Economy; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008; p. 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argonne National Laboratory. Report of the Basic Energy Science Workshop on Hydrogen Production, Storage and Use; Argonne National Laboratory: Lemont, IL, USA, 2003.

- Schlapbach, L. Hydrogen as a Fuel and its Storage for Mobility and Transport. MRS Bull. 2002, 27, 675–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, C.; Thomas, G.; Ordaz, C.; Satyapal, S. U.S. Department of Energy’s system targets for on-board vehicular hydrogen storage. Mater. Matters 2007, 2, 3. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Energy. H2 Storage Targets, Multi-Year Development and Demonstration Plan. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/eere/fuelcells/doe-technical-targets-onboard-hydrogenstorage-light-duty-vehicles (accessed on 24 June, 2020).

- Gupta, R.B. (Ed.) Hydrogen Fuel: Production, Transport and Storage; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008; p. 624. ISBN 9781420045758. [Google Scholar]

- Hirscher, M. Handbook of Hydrogen Storage: New Materials for Future Energy Storage; Wiley-VCH: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; p. 373. ISBN 978-527-62981-7. [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree, G.W.; Dresselhaus, M.S. The hydrogen fuel alternatives. MRS Bull. 2008, 33, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Züttel, A. Materials for hydrogen storage. Mater. Today 2003, 6, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, D.; Reilly, J.J.; Chellappa, R. Metal hydrides for vehicular applications: The state of the art. JOM 2006, 58, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirocak, D.E. Hydrogen Storage Technologies. In Nanostructured Materials for Next-Generation Energy Storage and Conversion; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 117–142. [Google Scholar]

- Lueking, A.D.; Yang, R.T. Hydrogen spillover to enhance hydrogen storage—Study of the effect of carbon physicochemical properties. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2004, 265, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- .Lam, C.-W.; James, J.T.; McCluskey, R.; Arepalli, S.; Hunter, R.L. A Review of Carbon Nanotube Toxicity and Assessment of Potential Occupational and Environmental Health Risks. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2006, 36, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.H.; Lee, E.J.; Lee, J.H.; So, K.P.; Lee, Y.H.; Bae, G.N.; Lee, S.-B.; Ji, J.H.; Cho, M.H.; Yu, I.J. Monitoring multiwalled carbon nanotube exposure in carbon nanotube research facility. Inhal. Toxicol. 2008, 20, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahluwalia, R.K.; Hua, T.Q.; Peng, J.K.; Lasher, S.; McKenney, K.; Sinha, J.; Gardiner, M. Technical assessment of cryo-compressed hydrogen storage tank systems for automotive applications. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2010, 35, 4171–4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirocak, D.E.; Srinivasan, S.S.; Goswami, D.Y.; Stefanakos, E.K. Synergistic effects of MWCNT and NB2O5 on the hydrogen storage characteristics of Li-nMg-B-N-H system. Am. Ceram. Soc. Mater. Chall. Altern. Renew. Energy 2016, 4, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Seayad, A.M.; Antonelli, D.M. Recent advances in hydrogen storage in metal-containing inorganic nanostructures and related materials. Adv. Mater. 2004, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuth, F. Hydrogen and hydrates. Nature 2005, 434, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuth, F.; Bogdanovic, B.; Felderhoff, M. Light metal hydrides and complex hydrides for hydrogen storage. Chem. Comm. 2004, 36, 2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKeown, N.B.; Gahnem, B.; Msayib, K.J.; Budd, P.M.; Tattershall, C.E.; Mahmood, K.; Tan, S.; Book, D.; Langmi, H.W.; Walton, A. A phthalocyanine clathrate of cubic symmetry containing interconnected solvent-filled voids of nanometer dimensions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 45, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fichtner, M. Nanotechnological aspects in materials for hydrogen storage. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2005, 7, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong-Foy, A.G.; Matzger, A.J.; Yaghi, O.M. Exceptional H2 saturation uptake in microporous metal-organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ströbel, R.; Garche, J.; Moseley, P.T.; Jörissen, L.; Wolf, G. Hydrogen storage by carbon materials. J. Power Sources 2006, 159, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Change, C.-W.; Lueking, A.D. Observation and simulation of hydrogen storage via spillover. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2018, 21, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.-W.; James, J.T.; McCluskey, R.; Hunter, R.L. Pulmonary toxicity of single-wall carbon nanotubes in mice 7 and 90days after intratracheal instillation. Toxicol. Sci. 2004, 77, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Lee, S.B.; Bae, G.N.; Jeon, K.S.; Yoon, J.U.; Sung, J.H.; Lee, B.G.; Lee, J.H.; Yang, J.S.; Kim, H.Y.; et al. Exposure assessment of carbon nanotube manufacturing workplaces. Inhal. Toxicol. 2010, 22, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, A.; Park, C.; Baker, R.T.K.; Rodriguez, N.M. Hydrogen Storage in Graphite Nanofibers. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 4253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heben, M.J.; Dillon, A.C.; Cheng, H.M.; Dresselhaus, M.S. Room temperature hydrogen storage in nanotubes. Science 2000, 287, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X. Polymerized carbon nitrogen nanobells and their field emission. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1999, 75, 3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.Y.; Liao, B.; Liu, M.; Wei, Y.L.; Lu, M.Q.; Chang, H.M. Hydrogen uptake in vapor-grown carbon nanofibers. Carbon 1999, 37, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Wu, X.; Lin, J.; Tan, K.L. High H2 Uptake by Alkali-Doped Carbon Nanotubes Under Ambient Pressure and Moderate Temperatures. Science 1999, 285, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zidan, R.; Rao, A.M. Doped Carbon Nanotubes for Hydrogen Storage; DOE Hydrogen Program, FY 2002 Progress Report 2002:231; US Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2003.

- Baburaj, E.G.; Froes, F.H.; Shutthanandam, V.; Thevuthasan, S. Low Cost Synthesis of Nanocrystalline Titanium Aluminides Interfacial; Chemistry and Engineering, Annual Report: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2000; p. 4-1. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, R.; Boily, S.; Zaluski, L.; Zaluka, A.; Tessier, P.; Strom-Olsen, J.O. Nanocrystalline materials for hydrogen storage. Innov. Met. Mater. 1995, 529. [Google Scholar]

- Varin, R.A.; Czujko, T.; Wronski, Z.S. Nanomaterials for Solid State Hydrogen Storage; Springer Publications: Berlin, Germany, 2009; p. 338. ISBN 978-0-387-77711-5. [Google Scholar]

- Zaluska, A.; Zaluski, L.; Strom-Olsen, J.O. Structure, catalysis and atomic reactions on the nano-scale: A systematic approach to metal hydrides for hydrogen storage. Appl. Phys. A 2001, 72, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, T.C.E.; Grant, D.M.; Walker, G.S. Synergistic effect of LiBH4+MgH2 as a potential reversible high capacity hydrogen storage material. Ceram. Trans. 2009, 202, 97. [Google Scholar]

- Niemann, M.U.; Srinivasan, S.S.; McGrath, K.; Kumar, A.; Goswami, D.Y.; Stefanakos, E.K. Nanocrystalline effects on the reversible hydrogen storage characteristics of complex hydrides. Ceram. Trans. 2009, 202, 111. [Google Scholar]

- Huot, J.; Liang, G.; Boily, S.; Van Neste, A.; Schulz, R. Structural study and hydrogen sorption kinetics of ball-milled magnesium hydride. J. Alloys Comp. 1999, 293–295, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanovic, B.; Schlichte, K.; Reiser, A. Thermodynamic Properties and Cyclic-Stability of the System Mg2FeH6. In Hydrogen Power: Theoretical and Engineering Solutions; Saetre, T.O., Ed.; Kluwer Academic: Dordercht, The Netherlands, 1991; p. 291. [Google Scholar]

- Zuttel, A.; Wenger, P.; Rentsch, S.; Sudan, S.; Mauron, P.; Emmenegger, C. LiBH4 a new hydrogen storage material. J. Power Sources 2003, 118, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandrock, G. A panoramic overview of hydrogen storage alloys from a gas reaction point of view. J. Alloys Comp. 1999, 293–295, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yvon, K.; Bertheville, B. Magnesium based ternary metal hydrides containing alkali and alkaline-earth elements. J. Alloys Comp. 2006, 425, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, K.-J.; Theodore, A.; Wu, C.-Y.; Cai, M. Hydrogen absorption/desorption kinetics of magnesium nano-nickel composites synthesized by dry particle coating technique. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2007, 32, 1860–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Wu, C.Z.; Wang, H.; Cheng, H.M.; Lu, G.Q. Effects of Carbon Nanotubes and Metal Catalysts on Hydrogen Storage in Magnesium Nanocomposites. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2006, 6, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.Z.; Wang, P.; Yao, X.; Liu, C.; Chen, C.M.; Lu, G.Q.; Cheng, H.M. Hydrogen storage properties of MgH2/SWNT composite prepared by ball milling. J. Alloys Comp. 2006, 420, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.R.; Anderson, P.A.; Edwards, P.P.; Gameson, I.; Prendergast, J.W.; Al-Mamouri, M.; Book, D.; Harris, I.R.; Speight, J.D.; Walton, A. Chemical activation of MgH2; a new route to superior hydrogen storage materials. Chem. Comm. 2005, 36, 2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W. (LiNH2-MgH2): A viable hydrogen storage system. J. Alloys Comp. 2004, 381, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vajo, J.J.; Skeith, S.L.; Mertens, F. Reversible Storage of Hydrogen in Destabilized LiBH4. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Huot, S.; Boily, A.; Van Neste, A.; Schultz, R. hydrogen storage properties of the mechanically milled MgH2-V nanocomposite. J. Alloys Compd. 1999, 291, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlapbach, L.; Zuttel, A. Hydrogen-storage materials for mobile applications. Nature 2001, 414, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grochala, W.; Edwards, P.P. Thermal decomposition of the non-interstitial hydrides for the storage and production of hydrogen. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanovic, B.; Schwickardi, M. Ti-doped alkali metal aluminum hydrides as potential novel reversible hydrogen storage materials. J. Alloys Comp. 1997, 253–254, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, C.M.; Zidan, R.A. Hydrogen Storage Materials and Method of Making by Dry Homogenization. U.S. Patent 6,471935, 29 October 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.; Xiong, Z.; Lou, J.; Lin, J.; Tan, K.L. Interaction of hydrogen with metal nitrides and imides. Nature 2002, 420, 302–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.H.; Ruckenstein, E. H2 Storage in Li3N. Temperature-Programmed Hydrogenation and Dehydrogenation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2003, 42, 5135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, M. Destabilized and Catalyzed Alkali Metal Borohydrides for Hydrogen Storage with Good Reversibility. U.S. Patent Application Publication 0194695A1, 31 August 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, S.; Escobar, D.; Jurczyk, M.; Goswami, Y.; Stefanankos, E. Nanocatalyst doping of Zn(BH4)2 for on-board hydrogen storage. J. Alloys Compd. 2008, 462, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Sudik, A.; Siegel, D.J.; Halliday, D.; Drews, A.; Carter, I.I.I.R.O.; Wolverton, C.; Lewis, G.J.; Sachtler, J.W.A.; Low, J.L.; et al. Hydrogen storage properties of 2LiNH2 + LiBH4 + MgH2. J. Alloys Compd. 2007, 446–447, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, G.J.; Sachtler, J.W.A.; Low, J.J.; Lesch, D.A.; Faheem, S.A.; Dosek, P.M.; Knight, L.M.; Halloran, L.; Jensen, C.M.; Yang, J.; et al. High throughput screening of the ternary LiNH2-MgH2-LiBH4 phase diagram. J. Alloys Compd. 2007, 446–447, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuttel, A. Hydrogen Storage Methods. Naturwissenschaften 2004, 91, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, S.H.; Choi, S.J.; Ryoo, R. Ordered nanoporous arrays of carbon supporting high dispersions of platinum nanoparticles. Nature 2001, 412, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, B.; Sankaran, M.; Schibioh, M.A. Carbon Nanomaterials: Are they appropriate candidates for hydrogen storage. Bull. Catal. Soc. India 2003, 2, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Nijkamp, M.G.; Raaymakers, J.E.M.J.; Van Dillen, A.J.; De Jong, K.P. Hydrogen storage using physisorption—Materials demands. Appl. Phys. A 2001, 72, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, A.C.; Jones, K.M.; Bekkedahl, T.A.; Kiang, C.H.; Bethune, D.S.; Heben, M.J. Storage of hydrogen in single-walled carbon nanotubes. Nature 1997, 386, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.M.F.J.; Coleman, K.S.; Green, M.L.J. Influence of catalyst metal particles on the hydrogen sorption of single-walled carbon nanotube materials. Nanotechnology 2005, 16, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroto, H.W.; Heath, J.R.; O’Broem, S.C. Curl RF, Smalley RE. C60: Buckminsterfullerene. Nature 1985, 318, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, Y.; Kawai, Y.; Koiwai, A.; Suzuki, N.; Haga, T.; Hioki, T.; Tange, K. IR characterizations of lithium imide and amide. J. Alloys Compd. 2005, 395, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stejskal, J. Polyaniline. Preparation of a Conducting Polymer; IUPAC Technical Report; International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry: Triangle Park, NC, USA, 2002; Volume 75, p. 857. [Google Scholar]

- MacDiarmid, A.G.; Epstein, A.J. A novel class of conducting polymers. Faraday Discuss. Chem. Soc. 1989, 88, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stejskal, J.; Kratochvil, P.; Jenkins, A.D. The formation of polyaniline and the nature of its structures. Polymer 1996, 37, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, D.C. Handbook of Organic Conductive Molecules and Polymers; Nalwa, H.S., Ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1997; Volume 2, p. 505. [Google Scholar]

- Stejskal, J.; Gilbert, R.G. Preparation of a conducting polymer. Pure Appl. Chem. 2002, 74, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virji, S.; Kaner, R.B.; Weiller, B.H. Hydrogen sensors based on conductivity changes in polyaniline nanofibers. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 22266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusalba, F.; Gouerec, P.; Vellers, D.; Belanger, D.J. Electrochemical characterization of polyaniline in nonaqueous electrolyte and its evaluation as electrode material for electrochemical supercapacitors. Electrochem. Soc. 2001, 148, A1–A6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossberg, K.; Paasch, G.; Dunsch, L.J. The influence of porosity and the nature of the charge storage capacitance on the impedance behaviour of electropolymerized polyaniline films. Electroanal. Chem. 1998, 443, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.J.; Song, K.S.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, T.H.; Choo, K. Hydrogen sorption in HCl treated polyaniline and polypyrrole, new potential hydrogen storage media. Prepr. Symp. Am. Chem. Soc. Div. Fuel Chem. 2002, 47, 790. [Google Scholar]

- Panella, B.; Kossykh, L.; Dettlaff-Weglikowska, U.; Hrischer, M.; Zerbi, G.; Roth, S. Volumetric measurement of hydrogen storage in HCl-treated polyaniline and polypyrrole. Synth. Met. 2005, 151, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeown, N.B.; Budd, P.M.; Book, D. Microporous polymers as potential hydrogen storage materials. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2007, 28, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.J.; Choo, K.; Kim, D.P.; Kim, J.W. H2 sorption in HCl-treated polyaniline and polypyrrole. Catal. Today 2007, 120, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurczyk, M.U.; Kumar, A.; Srinivasan, S.; Stefanakos, E. Polyaniline-based nanocomposite materials for hydrogen Storage. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2007, 32, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germain, J.; Frechet, J.M.J.; Svec, F.J. Hypercrosslinked polyanilines with nanoporous structure and high surface area: Potential adsorbents for hydrogen storage. Mater. Chem. 2007, 17, 4989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitin, A.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Ogasawara, H.; Dai, H.; Nilsson, A. Hydrogen storage in carbon nanotubes through the formation of stable C–H bonds. Nano Lett. 2008, 8, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Sim, K.S.; Kim, J.W. Synthesis and hydrogen storage of carbon nanofibers. Synth. Met. 2002, 126, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jing, X.J. Synthesis and hydrogen storage of carbon nanofibers. Synth. Met. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadek, A.Z.; Trinchi, A.; Wlodarski, W.; Kalantar-zadeh, K.; Galatsis, K.; Baker, C.; Kaner, R.B. A room temperature polyaniline nanofiber hydrogen gas sensor. IEEE Sens. 2005, 3, 207. [Google Scholar]

- Athawale, A.A.; Bhagwat, S.V.J.J. Synthesis and characterization of novel copper/polyaniline nanocomposite and application as a catalyst in the Wacker oxidation reaction. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2003, 89, 2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ouyang, J.; Ma, L.; Tseng, R.J.; Chu, C.W. Electrical Switching and Bistability in Organic/Polymeric Thin Films and Memory Devices. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2006, 16, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huczko, A. Template-based synthesis of nanomaterials. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 2000, 70, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, Y. Synthesis and applications of onedimensional nano-structured polyaniline: An overview. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2006, 134, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 101 Srinivasan, S.S.; Ratnadurai, R.; Niemann, M.U.; Phani, A.R.; Goswami, D.Y.; Stefanakos, E.K. Reversible hydrogen storage in electrospun polyaniline fibers. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2010, 35, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemann, M.U.; Srinivasan, S.S.; Phani, A.R.; Kumar, A.; Goswami, D.Y.; Stefanakos, E.K. Room temperature hydrogen storage in Polyaniline (PANI) nanofibers. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2009, 9, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Fan, L.; Fang, Y.; Yang, S. Electrochemistry of composite films of C60 and multiwalled carbon nanotubes: A robust conductive matrix for the fine dispersion of fullerenes. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2005, 413, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, A.A.S.; Purewal, J.; Wong-Foy, A.G.; Veenstra, M.; Matzger, A.J.; Siegel, D.J. Exceptional hydrogen storage by achieved by screening nearly half a million metal-organic frameworks. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1568. [Google Scholar]

- Roswell, J.L.C.; Spencer, E.C.; Eckert, E.C.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Yaghi, O.M. Effects of Functionalization, Catenation, and Variation of the Metal Oxide and Organic Linking Units on the Low-Pressure Hydrogen Adsorption Properties of Metal−Organic Frameworks. Science 2005, 309, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lukaszczuk, P.; Tripisciano, C.; Rümmeli, M.H.; Srenscek-Nazzal, J.; Pelech, I.; Kalenczuk, R.J.; Borowiak-Palen, E. Enhancement of the structure stability of MOF-5 confined to multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Phys. Status Solidi B 2010, 247, 2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Storage Parameter. | 2020 | 2025 |

|---|---|---|

| Gravimetric Hydrogen Storage Capacity (kg H2∙kg−1 material) | 0.045 | 0.055 |

| Volumetric Hydrogen Storage Capacity (kg H2∙L−1 material) | 0.030 | 0.040 |

| Hydrogen Delivery Temperature (°C) | −40/85 | −40/85 |

| System Fill Time (min; for 5 kg of H2) | 3–5 | 3–5 |

| Cycle Life (1/4 Tank to Full; non-dim) | 1500 | 1500 |

| Sample | Tdec (°C) | ΔHdec (kJ∙mol−1 H2) |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial MgH2 | 415 | 55.98 ± 0.50 |

| MgH2 (MC) | 375 | 46.35 ± 0.50 |

| MgH2 (MC)-nano-Ni | 225 | 36.50 ± 0.50 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Srinivasan, S.; Demirocak, D.E.; Kaushik, A.; Sharma, M.; Chaudhary, G.R.; Hickman, N.; Stefanakos, E. Reversible Hydrogen Storage Using Nanocomposites. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4618. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10134618

Srinivasan S, Demirocak DE, Kaushik A, Sharma M, Chaudhary GR, Hickman N, Stefanakos E. Reversible Hydrogen Storage Using Nanocomposites. Applied Sciences. 2020; 10(13):4618. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10134618

Chicago/Turabian StyleSrinivasan, Sesha, Dervis Emre Demirocak, Ajeet Kaushik, Meenu Sharma, Ganga Ram Chaudhary, Nicoleta Hickman, and Elias Stefanakos. 2020. "Reversible Hydrogen Storage Using Nanocomposites" Applied Sciences 10, no. 13: 4618. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10134618

APA StyleSrinivasan, S., Demirocak, D. E., Kaushik, A., Sharma, M., Chaudhary, G. R., Hickman, N., & Stefanakos, E. (2020). Reversible Hydrogen Storage Using Nanocomposites. Applied Sciences, 10(13), 4618. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10134618