Designing Organizational Eco-Map to Develop a Customer Value Proposition for a “Slow Tourism” Destination

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Business Models, Business Model Innovation, and Customer Value Proposition

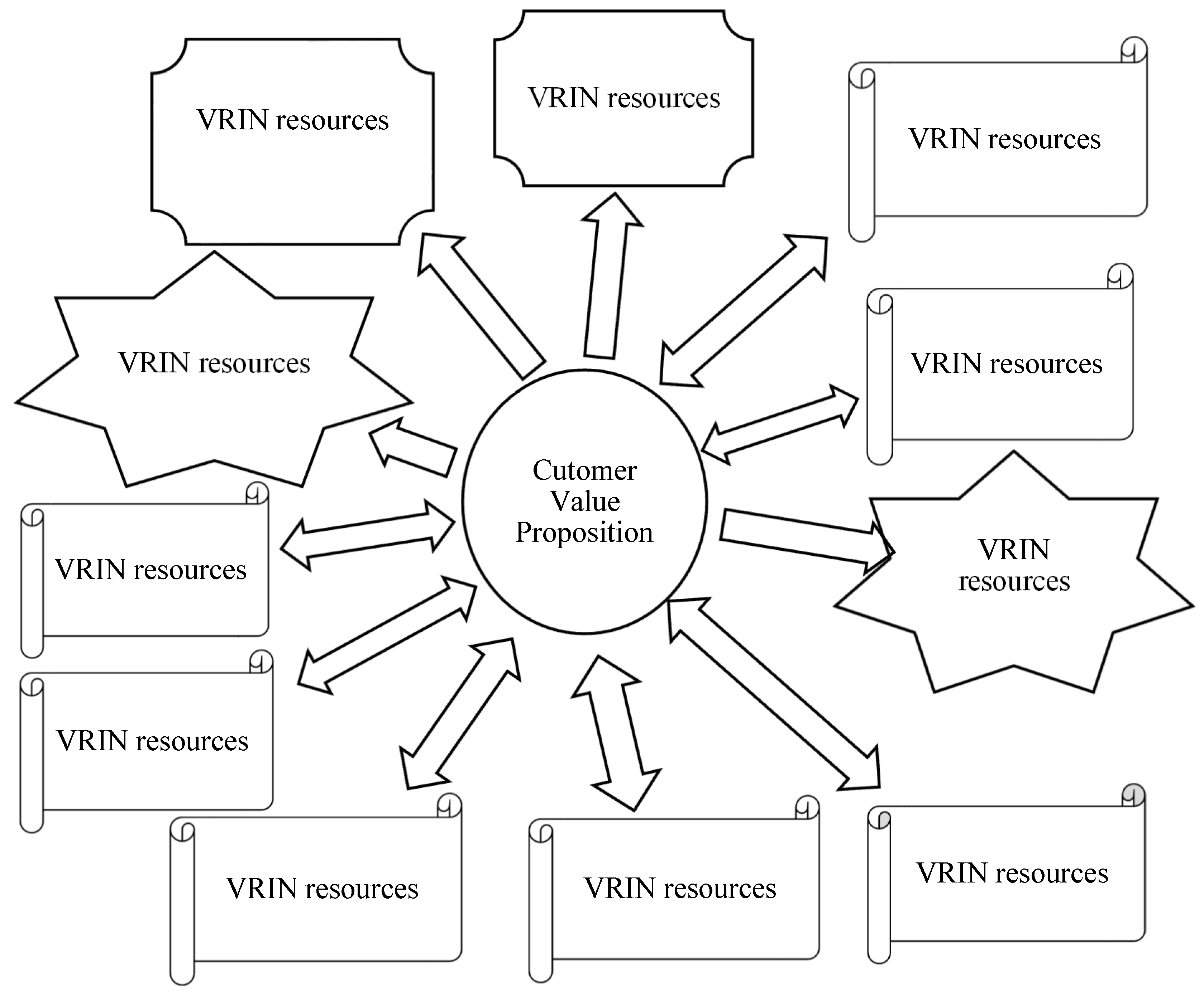

2.2. Resources Based View on Competitive Advantage, Cultural Resources, and the Organizational Eco-Map

2.3. Cultural Heritage Tourism, Food, and Relaxation Are “Slow Tourism” Destination

3. Case Study Research: Delivering New Customer Value Proposition of RCM

3.1. Research Design and Methodology

3.2. Data Analysis and Interpretation

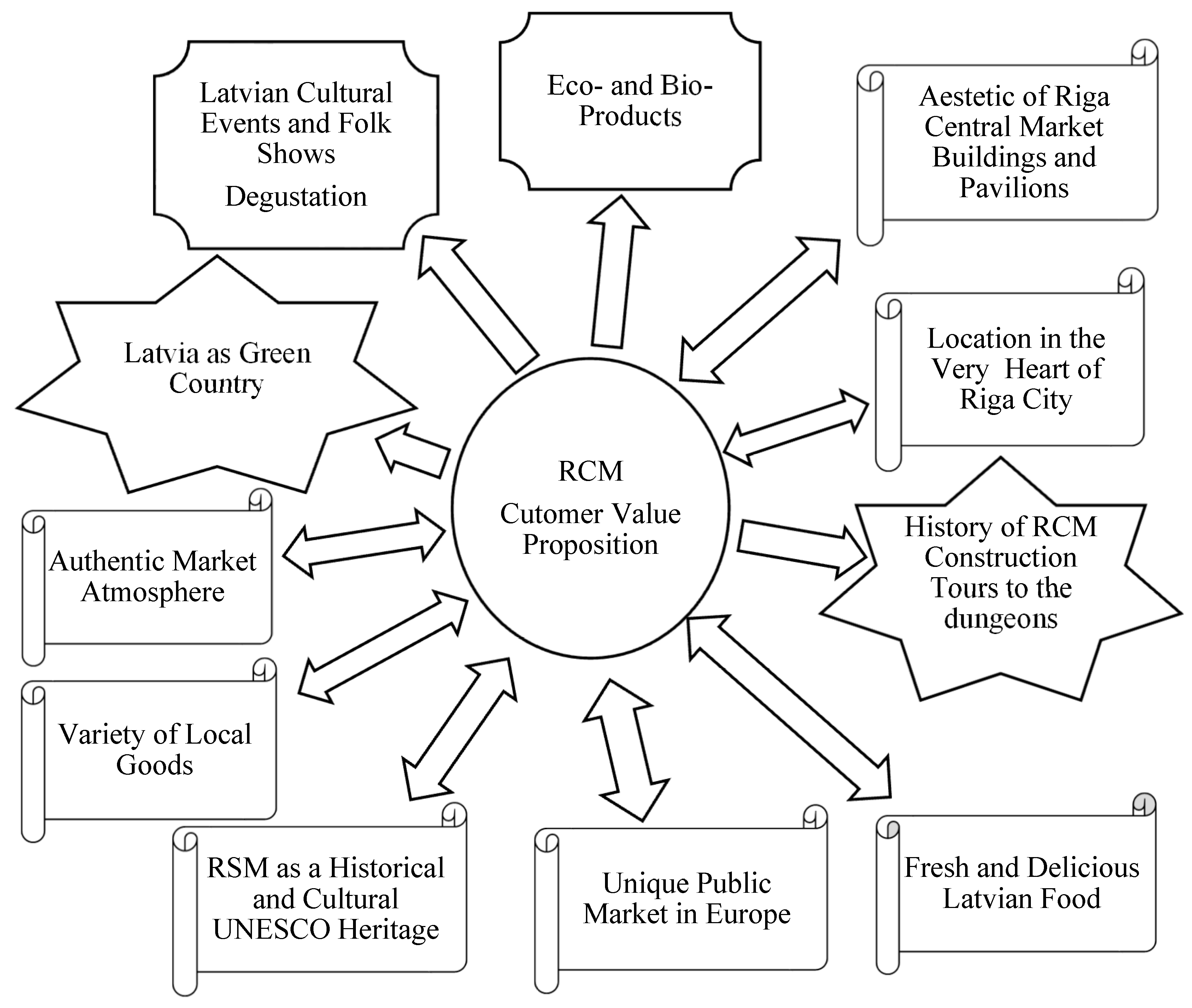

3.3. An Application of Organizational Eco-Map to Develop a Customer Value Proposition of Riga Central Market

4. Conclusions, Limitation of the Research, and Future Work

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adner, Ron. 2017. Ecosystem as Structure: An Actionable Construct for Strategy. Journal of Management 43: 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akama, John S. 2003. Measuring tourist satisfaction with Kenya’s wildlife safari: A case study of Tsavo West National Park. Tourism Management 24: 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, Raphael, and Christoph Zott. 2012. Creating value through business model innovation. MIT Sloan Management Review 53: 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Amit, Raphael, and Christoph Zott. 2016. Business Model Design: A Dynamic Capability Perspective. In The Oxford Handbook of Dynamic Capabilities. Edited by David J. Teece and Sohvi Heaton. Oxford: Oxford Handbooks. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, Jay. 1991. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. Journal of Management 17: 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battistella, Cinza, Maria Rosita Cagnina, Lucia Cicero, and Nadia Preghenella. 2018. Sustainable Business Models of SMEs: Challenges in Yacht Tourism Sector. Sustainability 10: 3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boniface, Priscilla. 2003. Tasting Tourism: Traveling for Food and Drink. Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Caffyn, Alison. 2007. Slow Tourism Alison Caffyn—Tourism Research Consultant. Available online: https://www.slideserve.com/Jimmy/ludlow (accessed on 24 May 2019).

- Capron, Laurence, Pierre Dussauge, and Will Mitchell. 1998. Resource redeployment following horizontal acquisitions in Europe and North America, 1988–1992. Strategic Management Journal 19: 631–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chassan, Jacob Bernard. 1979. Research Design in Clinical Psychology and Psychiatry. New York: Irvington Publishers Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, Henry. 2010. Business model innovation: opportunities and barriers. Long-Range Planning 43: 354–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirjevskis, Andrejs, and Iveta Ludviga. 2009. Managing the Culture of Diversity: National and Cultural Identities as the basis of Sustained Competitive Advantages in Globalised Markets. International Journal of Diversity in Organisations, Communities & Nations 9: 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Čirjevskis, Andrejs. 2016. Designing dynamically “signature business model” that support durable competitive advantage. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 2: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čirjevskis, Andrejs. 2017. Acquisition based dynamic capabilities and reinvention of business models: Bridging two perspectives together. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues 4: 516–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čirjevskis, Andrejs. 2019. The role of dynamic capabilities as drivers of business model innovation in mergers and acquisitions of technology-advanced firms. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 5: 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čirjevskis, Andrejs, and Arina Antonova. 2013. Exploring the Interrelation of Heterogeneous Cultural Resources and Customer Value Proposition: Organizational Eco Map. Paper presented at 2nd International Conference on Social Sciences and Society (ICSSS 2012), San Diego, CA, USA, 1–2 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Clegg, Frances G. 1990. Simple Statistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dallen, Timothy J., and Stephen W. Boyd. 2003. Heritage Tourism. Essex: Pearson Education Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, Janet E., Les M. Lumsdon, and Derrek Robbins. 2010. Slow Travel: Issues for Tourism and Climate Change. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 19: 281–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. 1989. Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review 14: 532–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estonian Word. 2017. The UN Classifies Estonia as a Northern European Country. Available online: https://estonianworld.com/life/un-reclassifies-estonia-northern-european-country/ (accessed on 24 July 2019).

- Foss, Nikolai J., and Tina Saebi. 2018. Business models and business model innovation: Between wicked and paradigmatic problems. Long-Range Planning 51: 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullagar, Simone, Kevin Markwell, and Erica Wilson, eds. 2012. Slow Tourism: Experiences and Mobilities. Bristol: Channel View. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman, Ann. 1995. Diagrammatic Assessment of Family Relationships. Families in Society 76: 111–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høgevold, Nils M., Göran Svensson, and Carmen Padin. 2015. A sustainable business model in services: An assessment and validation. International Journal of Services Sciences 7: 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojman, David, and Pippa Hunter-Jones. 2012. Wine tourism: Chilean wine regions and routes. Journal of Business Research 65: 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay Way Travel. 2016. Riga Central Market. Posted on April 2, by Stephan Delbo. Available online: https://jaywaytravel.com/blog/riga-central-market/ (accessed on 22 July 2019).

- Johnson, Mark W., Clayton M. Christensen, and Henning Kagermann. 2008. Reinventing your business model. Harvard Business Review 86: 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Konrath, Jill. 2006. Selling to Big Companies. Chicago: Dearborn Trade Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Kozak, Metin. 2001. Comparative assessment of tourist satisfaction with destinations across two nationalities. Tourism Management 22: 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejcie, Robert V., and Daryle W. Morgan. 1970. Determine sample size for research activities. Educational and Phycological Measurement 30: 607–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, Susan Ch. 2008. A Conceptual Framework for Business Model Research. Available online: https://domino.fov.uni-mb.si/proceedings.nsf/0/1e893ee544d680fec12574810042ac2d/$file/22lambert.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2019).

- Latvian Tourism Development Agency. 2010. The Latvian Tourism Marketing Strategy 2010–2015. Riga: Latvian Tourism Development Agency. [Google Scholar]

- Lindič, Jaka, and Carlos M Silva. 2011. Value proposition as a catalyst for a customer focused innovation. Management Decision Journal 49: 1694–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Guzman, Tomás, and Sandra Sánchez-Cañizar. 2012. Culinary tourism in Cordoba (Spain). British Food Journal 114: 168–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, Heike, and Paul L. Knox. 2006. Slow Cities: Sustainable Places in a Fast World. Journal of Urban Affairs 28: 321–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, Jennifer. 2007. An Appetite for Travel. Available online: http://www.travelagentcentral.com/niche-special-needs-travel/appetite-travel (accessed on 24 May 2019).

- Mihalič, Tanja, Vesna Žabkar, and Ljubica Knežević Cvelbar. 2012. A hotel sustainability business model: Evidence from Slovenia. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 20: 701–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, Alexander, and Yves Pigneur. 2010. Business Model Generation. Self-Published. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, Edith T. 1959. A Theory of the Growth of the Firm. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, Edith T., and Christos Pitelis. 2009. The Theory of the Growth of the Firm Penrose. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 665. [Google Scholar]

- Ragavan, Neethiahnanthan A., Hema Subramonian, and Saeed P. Sharif. 2014. Tourists’ perceptions of destination travel attributes: An application to International tourists to Kuala Lumpur. Procedia- Social and Behavioral Sciences 144: 403–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhold, Stephan, Florian J. Zach, and Dejan Krizaj. 2018. Business models in tourism—State of the art. Tourism Review. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/TR-02-2018-0027/full/html (accessed on 24 July 2019).

- Rigas Centraltirgus. n.d. Available online: https://www.rct.lv/en (accessed on 24 May 2019).

- Roscoe, John T. 1975. Fundamental Research Statistics for the Behavioural Sciences, 2nd ed. New York: Holt Rinehart & Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Rugman, Alan M., and Alain Verbeke. 2002. Strategic Management Journal, Edith Penrose’s contribution to the resource-based view of strategic management. Strategic Management Journal 23: 769–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, Runa, and Anup Sinha. 2015. The village as a social entrepreneur: Balancing conservation and livelihoods. Tourism Management Perspectives 16: 100–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scapens, Robert W. 1990. Researching management accounting practice: the role of case study. British Accounting Review 22: 259–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, Joseph A. 1936. The Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest, and the Business Cycle. Translated from the German by Redvers Opie. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, p. 255. [Google Scholar]

- Sekaran, Uma, and Roger Bougie. 2016. Research Methods for Business: A Skill-Building Approach. Chester: John Wiley & Sons, p. 420. [Google Scholar]

- Serdane, Zanda. 2017. Slow Tourism in a Slow Country: The Case of Latvia. Ph.D. thesis, Salford Business School, University of Salford, Salford, UK. Available online: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/43513/7/Zanda_Serdane_SLOW_TOURISM_IN_SLOW_COUNTRIES.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2019).

- Sims, Rebbeca. 2009. Food, place and authenticity: local food and the sustainable tourism experience. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 17: 321–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souto, Jaime E. 2015. Business model innovation and business concept innovation as the context of incremental innovation and radical innovation. Tourism Management 51: 142–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szromek, Adam R., and Krzysztof Herman. 2019. A Business Creation in Post-Industrial Tourism Objects: Case of the Industrial Monuments Route. Sustainability 11: 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szromek, Adam R., and Mateusz Naramski. 2019. A Business Model in Spa Tourism Enterprises: Case Study from Poland. Sustainability 11: 2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallman, Stephen, Yadong Luo, and Peter J. Buckley. 2018. Business model in global competition. Global Strategy Journal 8: 517–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, David J. 2018. Business models and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Planning 51: 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terhorst, Julia. 2019. Discovering New Forms of Tourism: Slow Tourism. Breda University of Applied Science. Available online: http://www.tourism-master.com/2013/01/22/discovering-new-forms-of-tourism-slow-tourism/ (accessed on 24 July 2019).

- Tham, Aaron, and Danny Huang. 2018. Game on! A new integrated resort business model. Tourism Review. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/TR-03-2017-0036/full/html?fullSc=1 (accessed on 24 July 2019).

- Weigert, Maxime. 2018. Jumia travel in Africa: Expanding the boundaries of the online travel agency business model. Tourism Review. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/TR-04-2017-0073/full/html (accessed on 24 July 2019).

- Zott, Christoph, Raphael Amit, and Lorenzo Massa. 2011. The Business Model: Recent Developments and Future Research. Journal of Management 37: 1019–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Key Resources | Definition |

|---|---|

| Physical | Assets like manufacturing facilities, buildings, vehicles, machinery, point-of-sales, and distribution networks |

| Intellectual | Brands, proprietary knowledge, patents and copyrights, partnerships, and customer databases |

| Human | Talented management and employees |

| Financial | Cash, lines of credit, or a stock option pool |

| Cultural | Stories and ritual; local food, drinks, and cuisine; historical and cultural heritage, community image and identity, overall unique atmosphere and environment (Chirjevskis and Ludviga 2009). |

| PERFA Framework of CVP | Definition | Relevance for RCM’s CVP |

|---|---|---|

| Performance | The way the organization works intending to serve best their customer while doing so profitably | Cultural and historical heritage, uniqueness and authentic market atmosphere, variety of local goods. |

| Ease of use | The degree to which customers believe using a certain product will be effort-free | Developed infrastructure at RCM, accessibility, and well-developed transport links. |

| Reliability | The ability of a product to deliver according to its expectations | RCM strives to live up to tourists’ expectations, yet some improvements are needed. |

| Flexibility | Organization’s ability to reallocate and reconfiguration its organizational resources, process and strategies as a response to environmental changes | Low level of flexibility, improvements needed. |

| Affectivity | Feeling or emotions associated with using organization products and services | Visiting RCM causes either very positive or very negative emotions, which is considered to be a strong point; improvements needed. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Čirjevskis, A. Designing Organizational Eco-Map to Develop a Customer Value Proposition for a “Slow Tourism” Destination. Adm. Sci. 2019, 9, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci9030057

Čirjevskis A. Designing Organizational Eco-Map to Develop a Customer Value Proposition for a “Slow Tourism” Destination. Administrative Sciences. 2019; 9(3):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci9030057

Chicago/Turabian StyleČirjevskis, Andrejs. 2019. "Designing Organizational Eco-Map to Develop a Customer Value Proposition for a “Slow Tourism” Destination" Administrative Sciences 9, no. 3: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci9030057

APA StyleČirjevskis, A. (2019). Designing Organizational Eco-Map to Develop a Customer Value Proposition for a “Slow Tourism” Destination. Administrative Sciences, 9(3), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci9030057