1. Introduction

The demand for European MBAs is constantly increasing (

Elliott and Soo 2013). This situation may be attributed to the ongoing “globalization” of business, which is creating a growing need for multidisciplinary and internationally-educated managers (

Jain and Stopford 2011). According to

Mercer et al. (

2010), “the effects of globalization are evident in education policy around the world—governments from the USA to China are driving their education systems to produce more skilled, more flexible, more adaptable employees”. The dynamic global business environment requires employees to be innovative and entrepreneurial.

Given this multilayered relevance of entrepreneurship to the world of work and careers, there is a strong interest in the emerging entrepreneurial mindset (

Obschonka et al. 2017). The development of human capital is strongly linked to the entrepreneurial spirit, because it helps to discover, create, and exploit business opportunities (

Jayawarna et al. 2014;

Marvel et al. 2016). Qualifications acquired in postgraduate education also influence entrepreneurial prospects through the acquisition of employment-related skills (

Greene and Saridakis 2008).

Therefore, the sector of MBA courses has grown rapidly in response to the demands of firms that feel they need to improve the training of their managers (

Busing and Palocsay 2016). An increasing number of universities and business schools provide such programs in different forms: full time, part time, executive, general management, distance learning, thematic or industry-focused programs, and so on.

At the same time, there have been questions about the design of their structures and contents with respect to the acquisition of the skills and capacities necessary for today’s labor market (

Warhurst 2011). Universities and business schools need to give a response to the needs of preparing students with the necessary skills to be globally competitive (

Sam and Van der Sijde 2014). However, are MBA programs really designed to foster entrepreneurial minds? This is our main research question.

To this end, universities, business schools, and MBA programs must become more entrepreneurial. Although there is a lack of agreement about the core factors and components (

Guerrero and Urbano 2012;

Rothaermel et al. 2007), some features or practices may be considered good practices in the process to become an entrepreneurial university. According to

Guerrero and Urbano (

2012), these features include formal characteristics like entrepreneurship education, informal characteristics like entrepreneurial climate, resources like human capital, and capabilities like networks or alliances.

Although the presence of some of these entrepreneurial features in several Spanish universities has been analyzed (

Fernández-Nogueira et al. 2018;

Sánchez-García et al. 2013), there is a lack of empirical studies that analyze the presence of these factors in the European MBA programs, so this study is relevant because it analyzes the presence or not of these features in a sample of 99 executive MBA programs at an international level. This study allows us to know the entrepreneurial level of the European business schools and universities, and to analyze what are the main areas of improvement in order to foster entrepreneurial thinking among the students (

Hernández-Sánchez et al. 2019).

The remainder of the paper contains six sections. First, in

Section 2, on the basis of a literature review, we identified the main traits that foster the emergence of entrepreneurial universities, and therefore, entrepreneurial minds.

Section 3 describes the research design and the methodology. In

Section 4, using a database of information from various European countries, we analyzed these characteristics in a sample of 99 executive or part-time MBAs. Discussion is shown in

Section 5 and some conclusions and further research are presented in

Section 6.

2. Theoretical Background

As the global business environment continues to change, MBA programs must adapt to prepare students for the latest trends and challenges in the business world. According to

Martin et al. (

2011), an interdisciplinary approach to education is necessary to enhance entrepreneurial minds; students must develop productive thinking and interpersonal competence, and they must embrace diversity (

Ploum et al. 2018;

RezaeiZadeh et al. 2017). In the literature, some theoretical models try to explain the phenomenon of entrepreneurial universities (

Kirby 2006;

Rothaermel et al. 2007). Entrepreneurial universities need to become entrepreneurial organizations—their members need to become potential entrepreneurs and their interactions with the environment need to follow an entrepreneurial pattern (

Röpke 1998).

Adopting the Institutional Economics and the Resource-Based View,

Guerrero and Urbano (

2012) integrate both factors—formal and informal factors related to the environment and resources and capabilities—involved in the development of entrepreneurial universities. Based on this model, we study some features that can be included in those categories, namely, entrepreneurial subjects, language of instruction and workload (formal features), internationality, international accreditations, lessons at international partner institutions, and students´ prior work (resources and capabilities).

2.1. Entrepreneurship Subjects

The presence and availability of subjects that are linked to entrepreneurship may be important for the generation of a positive entrepreneurial climate (

Bergmann et al. 2018). On this line,

Geissler et al. (

2010) found that the existence and quality of entrepreneurship courses is the most relevant variable affecting the perceived entrepreneurial climate of a university. The offering of specific courses on entrepreneurship in an MBA program not only provides students with capabilities but also generates a positive climate that can foster their entrepreneurial intentions.

2.2. Language of Instruction

Interpersonal skills are core competences that must be developed to foster entrepreneurship (

Ploum et al. 2018;

RezaeiZadeh et al. 2017). Language ability is an essential resource to develop interpersonal skills. Language ability permits communication, dialogue, and information exchange, which affect trust, rapport, and legitimacy. Since global firms demand managers who are able to succeed across national, cultural, and linguistic boundaries, it seems only appropriate for MBA programs intentionally to integrate foreign languages into their courses.

Moreover, nowadays, in landscapes dominated by intensifying internationalization and globalization, English language ability and proficiency are considered to be an essential cultural resource to foster international entrepreneurship (

Hurmerinta et al. 2015;

Isenberg 2008). Language ability functions as a core resource for born-global and firms in the process of internationalization to meet the needs of overseas markets (

Johnstone et al. 2018).

2.3. International Students

2.4. Internationality of Faculty Members

“Being co-taught” by lecturers from other universities and countries is positive, because it enhances students’ global thinking and fosters the sharing of alternative cultural perspectives. Adding faculty members from other countries or taking sabbaticals in various parts of the world may enrich institutions’ teaching. Additionally, faculty members may be actively involved in international business associations to improve their knowledge (

Kedia and Englis 2011) and foster entrepreneurship.

2.5. International Accreditations

Rankings and accreditations provide institutions with a strong quality signal towards the market. Thus, the strong brand image and reputation resulting from international accreditations enable them to acquire the best students (

David et al. 2011;

Gander 2015). Creating social capital with the best students attracts the best students. This climate, due to the presence of the most talented human resources, enhances the opportunities to learn of the best and these in turn enhance entrepreneurship.

Moreover, accreditations increase the commitment of the alumni to the academic institution (

Gallo 2013). The contact of the alumni with the institution can generate resources for the program (

Farrow and Yuan 2011). It may also produce opportunities for collaboration with alumni through technology transfer, content design, or lectures (

Plewa et al. 2015). These factors enhance opportunity identification, which is a component of productive thinking, a core competence of entrepreneurship (

Ploum et al. 2018).

2.6. Lessons at International Partner Institutions

Institutions can arrange lessons from international partner institutions or offer consortial MBA programs, in which two or more business schools run an MBA jointly. Programs in these cases include lessons at partner institutions in different countries (

Tadaki and Tremewan 2013).

These global alliances create opportunities for mutual learning among members, managers, faculty members, and students. Alliances also facilitate interactions among members and create opportunities for the joining and expansion of networks (

Gunn and Mintrom 2013) as well as opportunities to transfer knowledge between the partner universities (

Sutrisno and Pillay 2015).

Lessons at an international partner institution enable students to develop global awareness, global understanding, and global competences (

Kedia and Englis 2011). These enhance their adaptability and the possibility of developing their professional career in diverse industrial, organizational, and cultural contexts. Orientation towards learning, knowledge transfer, and networking are core elements of entrepreneurship (

Baron and Markman 2000;

Byrne and Toutain 2014;

Byrne et al. 2016;

Minniti and Bygrave 2001), so lessons at international partner institutions enhance entrepreneurial capabilities.

2.7. Workload

On the one hand, the greater the number of credits of a course, the greater the development of knowledge and competencies and the opportunity for building valuable relationships with other students and with lecturers (

Prince et al. 2014). On the other hand, the size may extend the duration of the studies, and students might lose interesting business opportunities.

Many MBAs aimed at managers are designed with a high number of credits but concentrate them in short periods of time, with a high workload (in terms of a greater number of credits per month). Although this solution avoids the problem of a lack of training, a heavy workload limits the availability of time for informal contact, a core element of entrepreneurship.

2.8. Prior Work Experience

Early work experience provides students with a variety of resources and skills that are distinct from those acquired via educational attainment. Work experience also enhances multidisciplinary knowledge. Both are positive in fostering an entrepreneurial mindset.

Part-time work provides appropriate human capital for developing an entrepreneurial career later in life (

Hickie 2011). Prior work experience also helps to develop a wider social network, which is an invaluable resource for future entrepreneurial endeavors (

Painter 2010) and fosters the development of personal interrelations, a core competence of entrepreneurship.

Students’ work allows them to gain better knowledge of the interrelationships between different functional areas and foster the development of the interpersonal qualities that they need to progress in the business area. MBAs in which students have longer work experience will facilitate the emergence of business opportunities.

3. Research Design and Methods

To achieve the second purpose of this research, we studied the European MBA program market, analyzing the presence of these characteristics in a sample of European MBAs.

3.1. Research Design

The population under study include executive and part-time MBA programs in five big countries in Western Europe (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK). These programs are targeted at active managers that need to coordinate the scheduling of the MBA with their professional activities. Only offline programs were included, since the characteristics of online programs are too different from those of offline programs. Finally, those MBA programs specialized in an industry or activity (e.g., MBAs in logistics or in banking) were also excluded.

A list of 297 European MBA programs was obtained using several sources of information. The directors or deans of the respective business schools and faculties were contacted by email and invited to take part in this research by filling out an online questionnaire. In those cases in which there were no response, up to two reminder emails were made, as well as telephone calls to increase the final response rate. The final sample consisted of a total of 99 part-time or executive MBA programs; 53 of them were master programs offered by public institutions and 46 were offered by private ones.

3.2. Questionnaire

The questionnaire was structured in three sections. In the first section, objective data about the MBAs was collected: duration, number of credits (total and by types: core, elective, etc.), previous professional experience of the students, cooperation agreements and percentage of credits in the cooperating institutions, price, quality accreditations of the program, performance ratios, and degree of internationalization (number of campuses that the respective MBA program offers, percentage of international students, teaching languages, percentage of international lecturers, percentage of lessons at international partner institutions, whether it is a double-degree MBA program, and percentage of students participating in international exchanges). Since only objective data were required, it was not necessary to use psychometric scales in this block; the respondents were directly asked to give us the corresponding data for each variable. All the variables used in this work were included in this first section.

The second section included several scales concerning the presence or relevance of different attributes of the MBA program. The contact information, along with information about the characteristics of the business school or university (public/private status, size, and so on) was collected in the third section.

4. A Descriptive Analysis of the European MBA Programs’ Characteristics

In this section, we will carry out a descriptive analysis of the characteristics of the European MBA programs in the sample. We will focus on those variables that might foster entrepreneurial behavior, as shown in

Table 1.

4.1. Entrepreneurial Content

Of the MBA programs, 41.4% offer a subject that refers explicitly to entrepreneurship, being—along with corporate finance and marketing/communication—one of the most frequently elected courses offered. Although there are other subjects linked to entrepreneurship that are offered by a few programs in the sample (e.g., leadership, business development, or creativity), most of the programs do not offer specific subjects to cover this area.

4.2. Total CPs

The total credits of an MBA program quantify its total workload, independently of chronological distribution. Most of the examined programs include 90 CPs. The average, however, is 84.12 CPs, as shown in

Table 1. The spread of 75 CPs results from a minimum value of 45 CPs and several MBA programs with 120 CPs. It is worth noting that there are MBA programs that involve 2 to nearly 3 times the workload of some other MBA programs.

4.3. Duration

The planned duration of an MBA program is the period during which a student is bound to the program. The average duration of all the examined programs is 22.35 months, as shown in

Table 1, while most of the programs (the mode) run for 24 months.

The standard deviation of 5.13 months indicates a moderate average deviation from the average duration. The spread in duration of 27 months (a minimum of 9 months and a maximum of 36 months) indicates that there are short and long MBA programs. Most of the MBA programs, however, last between 18 and 24 months.

4.4. Relative Workload (cp/m)

As described above, the relative workload is calculated by dividing the total number of credits of an MBA program by the total duration measured in months. Most of the programs—80 out of 99—require 3 to 5 cp/m. The sample average of the workload per month is 3.89 cp/m, with a low standard deviation of 0.98 cp/month, as shown in

Table 1. However, the total spread of 5.67 cp/month indicates that there are outliers. These outliers can be detected in both directions. The minimum value is 1.83 cp/m and the maximum is 7.50 cp/m, as shown in

Table 1.

4.5. Students’ Prior Work Experience

Students’ prior work experience, measured in years, indicates MBA students’ professional background level and the type of curriculum and content that they require. The arithmetic average of prior professional work experience is 6.56 years, with a large standard deviation of 3.50 years, as shown in

Table 1. The sample includes part-time (PT) MBA programs that accept students with 0 to 1 year of pre-MBA work experience and programs with students who have 14 years’ work experience on average. In addition, the mode is 5 years; thus, the heterogeneity of the pre-MBA work experience among the programs in this study is rather high.

4.6. International Accreditation

International accreditation is one of the most obvious positioning instruments. On average, each business school has 0.84 international accreditations, as shown in

Table 1.

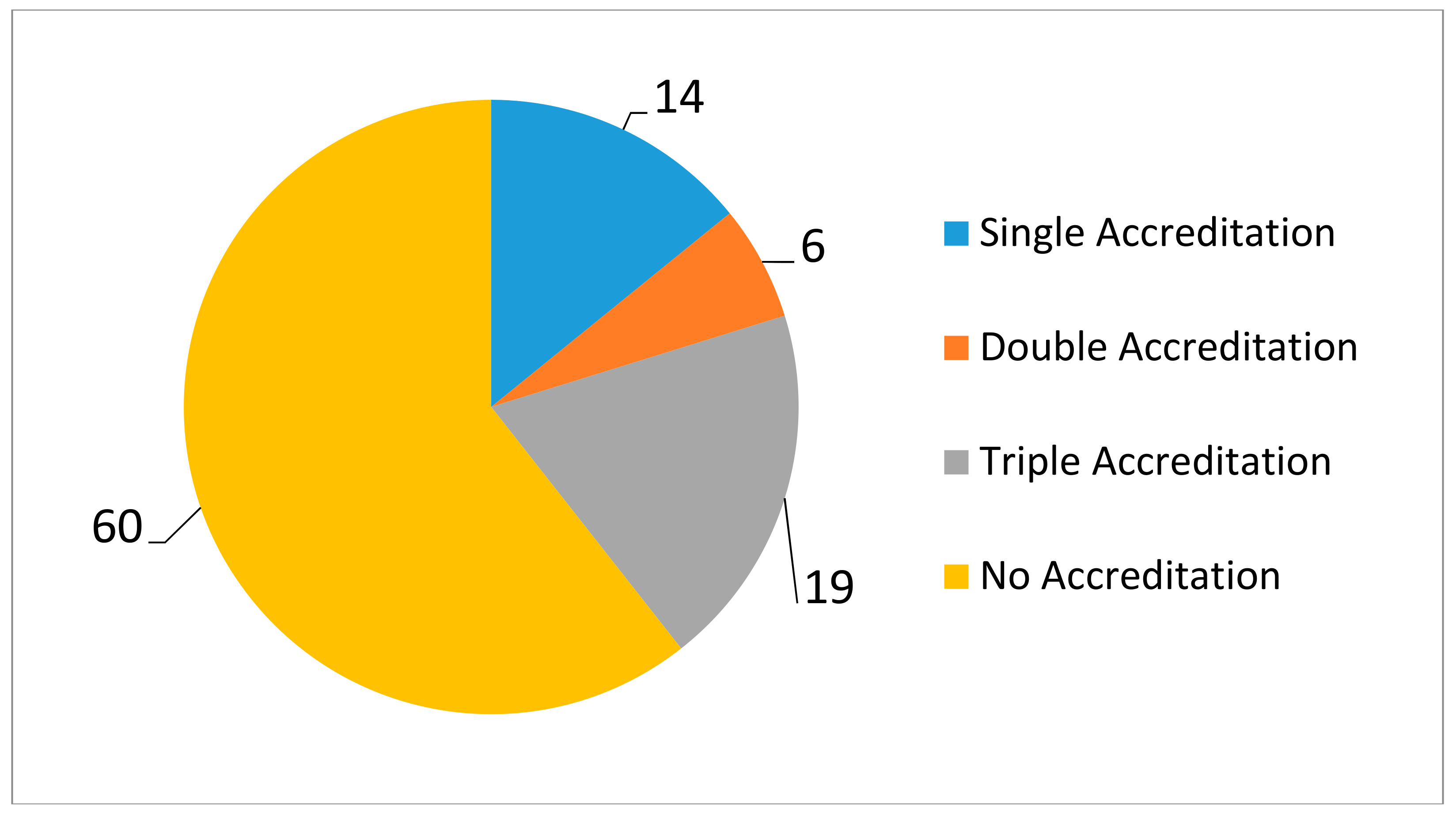

Figure 1 shows the distribution of international accreditation among all 99 PT GM MBA programs that were considered in this study, arranged by the number of international accreditations.

Most of the programs are offered by business schools that are not accredited by one of the three internationally most relevant accreditation agencies: EQUIS, AMBA, and AACSB. However, 39 of the business schools are single, double, or even triple accredited. Business schools can decide which accreditations correspond to their individual purposes. Thus, different types of accreditation combinations may occur.

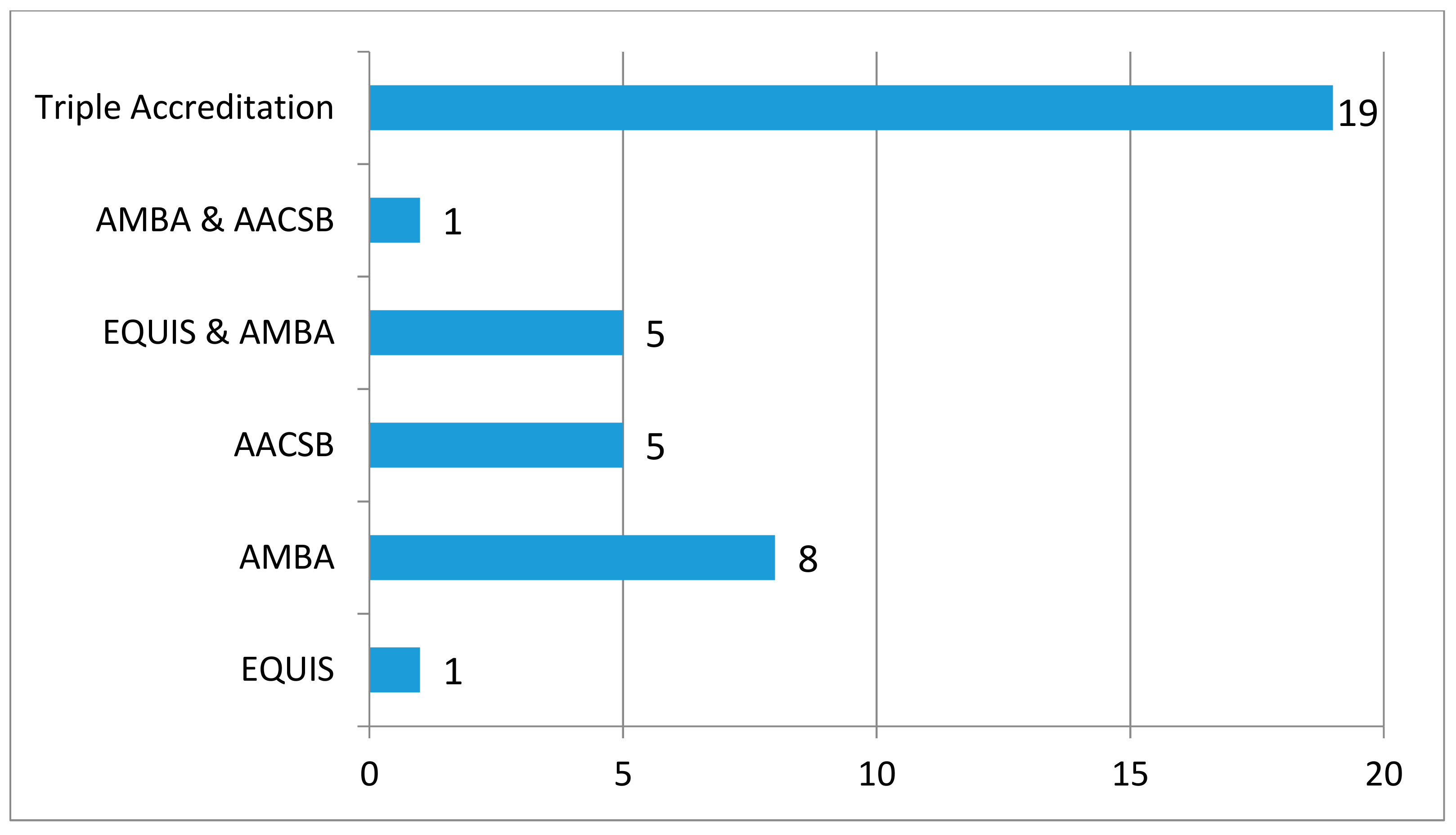

Figure 2 specifies the types of international accreditation combinations that the business schools have.

There are 19 programs with triple accreditation, 6 with double accreditation, and 14 with single accreditation, as shown in

Figure 2. The sample size is small for deducing substantial assumptions; however, it seems that there is a tendency within the group of accredited programs towards either single or triple accreditation. In other words, double-accredited programs have presumably yet to take the additional hurdle of triple accreditation.

4.7. Language of Instruction

The total arithmetic average reaches a level of 65.38% for English as the teaching language, as shown in

Table 1. Three strategies seem to exist for the teaching language. Most of the programs—55 of 99—are run entirely in English, while only 14 programs are taught entirely in the local language, which is not English. The remaining 30 programs are run with a mixture of English and the local language.

The MBA programs located in the United Kingdom, of course, are taught entirely in English. This fact could distort the results, but the intention of this study is to consider the European PT GM MBA market in which the teaching language plays an essential role for MBA program positioning in the United Kingdom and outside the United Kingdom.

4.8. Internationality of Students

The average proportion of international students in the MBAs of the sample is 34.43%, as shown in

Table 1. The standard deviation of 30.01 is high and indicates a large spread around the arithmetic average. Most of the programs include international students.

4.9. Internationality of Faculty Members

On average, 33.82% of faculty members have an international background, as shown in

Table 1. The standard deviation of 27.29 is high when compared with the arithmetic average. However, there are extreme values of 0.00% and 100.0%, while the mode reaches approximately 30.0%.

Programs with faculties that are entirely from international backgrounds may seem dubious. This study, however, includes MBA programs that are offered on a business school’s foreign subsidiary campus. In such cases, native lecturers are often sent to the subsidiary to teach, a situation that may lead to a high percentage of international lecturers.

4.10. Lessons at International Partner Institutions in PT GM MBA Programs

The arithmetic average of lessons at international partner institutions is 12.44%, while the standard deviation amounts to 21.4, as shown in

Table 1. Of the 99 programs, 47 do not include lessons at international partner institutions at all. In contrast, lessons at international partner institutions constitute 5% to 12% of the curricula for a large group of 26 programs. A further 16 programs include 15% to 30% of their curricula at international partner institutions. Of the 99 programs, 10 run 50% or more of their curricula at partner institutions.

In particular, consortial MBA programs, in which two or more business schools jointly run an MBA, may reach higher percentages for this variable. The one program that has 100% of its lessons at partner institutions is a global MBA program that arranges lessons entirely at partner institutions in different countries.

5. Discussion

The essential skills and abilities for entrepreneurial behavior are built up through primary, secondary, and higher education (

Jayawarna et al. 2014). In this study, we explored European MBA programs to determine the extent to which their characteristics are in line with the development of entrepreneurial thinking and entrepreneurial competences.

To this end, we examined several characteristics of the European PT MBA market. In this regard, the research focus was on part-time non-specialized MBA (PT MBA) programs, which represent a subset of MBAs within the bandwidth of MBA programs (full time, part time, distance, online, thematic focus, general management, etc.). Nevertheless, even in this area, the examined PT MBA programs show a heterogeneous configuration in terms of their characteristics. Nearly every examined variable that describes a program characteristic showed wide dispersion.

Are the characteristics of the European PT MBA programs adequate for fostering entrepreneurship? According to the significant heterogeneity, no “typical” European PT MBA program can be defined. The diversity of students and requirements reflects the heterogeneity of the programs. Nevertheless, we can identify the entrepreneurship-promoting characteristics that are more widespread.

Entrepreneurship courses are offered in 41.4% of the MBAs. This finding suggests that, in most of the programs, the entrepreneurial orientation is not a priority. Nevertheless, the lack of this subject does not mean that an MBA program has no interest for potential entrepreneurs or for developing entrepreneurial managers. Most of the subjects and opportunities offered by standard MBA programs are valuable for entrepreneurship. In any case, entrepreneurship education at university level may be the key to success in the development of entrepreneurial competences (

Barba-Sánchez and Atienza-Sahuquillo 2018;

González Moreno et al. 2019;

Hu et al. 2018). This is important not only for future entrepreneurs, but also for employees of entrepreneurial firms. That is why it is necessary to include entrepreneurship education in a higher number of MBA programs.

The statistical results show that the use of English as the teaching language is the most frequent characteristic. More than 50% of the sample use this language as the only teaching language, and more than 75% use it in at least 25% of the lessons. In part, this is caused by the presence of British business schools in our sample; nevertheless, even when excluding these cases (21.1% of MBAs in the sample from the UK), we can see that the use of English as a teaching language is widespread in Europe. Because interpersonal skills are core competences that must be developed to foster entrepreneurship (

Ploum et al. 2018), and ability in a foreign language is an essential resource to develop interpersonal skills in the landscapes dominated by globalization, these figures are positive for fostering entrepreneurial minds.

Internationalization is very salient in the MBA market. At least 25% of students and 30% of faculty members are foreign in the majority of the master’s courses in the sample. This situation enables students to build relationships and network with international students and lecturers, which enhance creativity, innovation, and entrepreneurship (

RezaeiZadeh et al. 2017).

The internationalization of the MBAs is also reflected in the growing existence of international alliances between business schools. We found that, in most of the programs (53%), some lessons are taught at international partner institutions. This fosters the sharing of alternative cultural perspectives and enhances the students’ ability to think globally (

Kedia and Englis 2011), which is important to promote an entrepreneurial spirit.

In contrast, the number of MBA programs and business schools that have been awarded at least one international accreditation (EQUIS, AMBA, or AACSB) is low (39.4%). Accreditations are important, because the quality of education is difficult to evaluate before being experienced, so accreditations serve as critical signal for quality (

Plewa et al. 2016). Moreover, they enhance the commitment of the alumni to the academic institution (

Gallo 2013) and help in attracting the best students. Both are important for creating social capital, which enhances opportunities to learn and productive thinking, essential competences of entrepreneurship (

Ploum et al. 2018). However, the accreditation processes are especially demanding, and not all the business schools are willing to make the necessary efforts and investments to meet the requirements.

Since part-time MBAs are mainly oriented towards professionals, it is not surprising that almost all the MBAs have students with previous work experience. However, there are relevant differences concerning the average experience of the students. Among the MBAs, 72% reach averages of five or more years of students’ previous experience. Early work experience makes the generation of sector-focalized ideas more probable as business opportunities, which are interesting resources for future entrepreneurial endeavors (

Painter 2010).

The effect of the size of the master’s course (measured as the total number of credits or the duration) and the workload (measured as credits per month) on the generation of entrepreneurial intentions is twofold. On the one hand, they foster the development of knowledge and competencies (

Prince et al. 2014) and the opportunity for building relationships. On the other hand, the size may extend the duration of the studies, losing the student interesting business opportunities. A greater workload (in terms of a larger number of credits per month) can compensate for this effect but has the disadvantage that it makes the interactions that favor creativity and entrepreneurship difficult. In any case, only 8% of the sample has a workload of more than five credits per month.

6. Conclusions

Are European MBA programs really designed to foster entrepreneurial minds? This is our main research question. Fostering entrepreneurial minds is linked to the concept of entrepreneurial universities. Entrepreneurial universities have some features that favor the development of entrepreneurial climate and entrepreneurial minds. Using the model proposed by

Guerrero and Urbano (

2012), we studied the presence or absence of several features, resources, and capabilities in a sample of 99 European MBA programs. The results of this study indicate that European MBAs are oriented to the development of entrepreneurial minds in some aspects, but they are far from contributing to achieve this objective in others.

The main indicator of a lack of entrepreneurial orientation is related to the absence of an entrepreneurial education subject. In this sense, less than half of the MBA programs have this subject in their curriculum. Entrepreneurship is related with greater entrepreneurial ability levels (

Millan et al. 2014). However, most MBAs do not offer this subject even as an elective. The MBA programs do not have to be necessarily oriented to entrepreneurship, they may have other priorities, but the total absence of a subject like this is a lack that limits the future possibilities of the students’ action.

However, this pessimistic view is partly compensated by the fact that many programs do have other characteristics that can support in a more indirect way the future entrepreneurial action of the students. For instance, the analysis of the internationalization of the programs showed better results. English is the language of instruction more extended, which favors internationalization among students and teachers. Moreover, the presence of alliances with international partners is not uncommon.

Some conclusions for directors of business schools can be drawn from this study. A starting premise in this research is that entrepreneurship education is useful in higher education irrespective of the labor market choices. Those highly educated individuals who do not select into entrepreneurship but instead become employees also benefit from education in entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurial attitudes and skills are also important for managers, providing creativity and innovation essential for internal entrepreneurship in the organization. Moreover, the entrepreneurial activity on the part of the employees of the company can result in new spinoff firms, which is an interesting way for corporate growth.

However, in this research we observed that entrepreneurship education has hardly a marginal position within the MBA programs in Europe. There is still a lot to do in this field. On the one hand, the incorporation of at least one elective course on entrepreneurship is a pending task in most programs. On the other hand, although several favorable attributes for entrepreneurship (e.g., internationalization at the level of students and teachers) are present in many programs, there is also much to be done here. The search for academic partners and the attainment of international accreditations would be useful complements to improve the entrepreneurial orientation of the programs.

This study includes limitations that need to be considered. Further investigation can help to reduce these limitations. This study examined the supply side of the European PT MBA market from a managerial point of view. It would be interesting to complement this approach with the student perspective.

The examined MBA programs’ characteristics were chosen from a literature review based on the researchers’ perceptions. The selection of the most appropriate variables may be discussed. Moreover, the effects of some variables on entrepreneurial attitudes are not clear. For instance, the workload of the program might have opposite effects depending on the specific stage of the potential entrepreneur’s career. In earlier stages, a long MBA program with a low workload may be better to allow time for interactions and the acquisition of experiences; however, in later stages, they could prefer a short duration of the program and a high workload.

The descriptive nature of this study does not allow for causal inferences. Further research may address these types of inferences. The results obtained raise new research questions; for example, are students who are interested in entrepreneurship more prone to choose an accredited MBA than non-interested students, and are they more interested in short-duration programs? To gain a deeper understanding of the MBA programs’ market, further research is recommended.