Abstract

The spur of innovative startups has provided an unprecedented opportunity for female entrepreneurship. However, the mainstream literature on startups has elaborated a gender performance gap hypothesis. Considering the speed of technological, social, and cultural changes that have taken place in this millennium, we wonder if this gap can still be found today, with particular reference to new technology-based ventures. A financial analysis has been conducted on a sample of innovative Italian startups, and the following variables have been used to assess the company’s success: (i) size, (ii) profitability, (iii) efficiency, (iv) financial structure, and (v) financial management. Our results reveal that as far as financial performance is concerned, innovative female-led startups do not lag behind male ones in terms of dimension, company profitability, efficiency, and financial management. However, findings confirmed, even for our sample, that female businesses raise, on average, a lower amount of financial resources in comparison to men.

1. Introduction

Female businesses are one of the fastest growing entrepreneurial populations in the world, and can make significant contributions to the innovation, employment, and wealth creation of all economies around the world (Brush et al. 2009; Hughes et al. 2012; Jennings and Brush 2013; Block et al. 2017). They also offer an answer in terms of self-employment to overcome the crisis of unemployment afflicting certain economies.

However, the empowerment of women in the main entrepreneurial ecosystems (Berger and Kuckertz 2016) is still contained in both the more developed and emerging countries, never exceeding 18% of the population of startups (Startup Genome 2018). In rational terms, the fact that women do not actively participate in the economic growth of GDP is undoubtedly a loss not only of wealth, but also of competitiveness, especially in a knowledge economy in which the entrepreneurial capital is increasingly a precious resource for the development of a country (Erikson 2002; Demartini and Paoloni 2014).

Another interesting aspect, to emphasise the contribution that women can make to a knowledge economy, is that in most advanced economies (but not only), the level of female education is comparable to that of men. Moreover, it has also grown in areas of knowledge known as disciplines of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM), which is traditionally a male domain (Beede et al. 2011).

Starting from the undisputed statistical evidence of a lower quantitative presence of female business owners, we are interested in understanding the strengths and weaknesses of female entrepreneurship today. Our study specifically aims at discussing the mainstream literature that found a gender gap, known as “the gender underperformance hypothesis” (Du Rietz and Henrekson 2000; Gatewood et al. 2003 for a literature review). In fact, most of the previous studies have found evidence at the aggregate level that female entrepreneurs tend to underperform compared to men (Rosa et al. 1996; Fairlie and Robb 2009).

Our study focuses on measuring the success of female companies, with particular reference to new technology-based ventures (Kuschel and Lepeley 2016). The latter are worthy of special attention because they can offer new business models and management styles useful for those who (entrepreneurs, consultants, politicians, trade associations, educators) are concerned with fostering the development of female entrepreneurship.

Our research question is as follows:

- Are innovative female-led startups less successful than male ones?

In the literature, there are two diverging views.

The mainstream literature, in line with the theory of resources (Alvarez and Busenitz 2001), considers that this gap is attributable to the limited resources of female startups, mainly due to the insufficient previous professional experience of the founders (Fairlie and Robb 2009) and a greater difficulty in accessing the capital market (Gatewood et al. 2009) and social networks (Aldrich 1989; Autio et al. 1997).

Other authors justify the lower profitability of female companies in the light of a lower risk appetite of women compared to men (Harris and Jenkins 2006). Because of this different attitude, female entrepreneurs are more oriented towards making choices that are positioned on a different and lower point on the risk-return curve (He et al. 2008).

On the other hand, there is an emerging stream of research, which considers that women in business, entrepreneurs and executives, aim for different goals, compared to those of men, being more interested in achieving a work-life balance, workers’ well-being, and community welfare with respect to mere corporate profit (Justo et al. 2015). For this reason, the success of women’s businesses cannot be measured and evaluated with the conventional performance indicators used in previous studies.

Our research draws on this debate and analyses the financial performance of a selected sample of innovative female-led startups. Considering the merciless speed of technological, social, and cultural changes, we wonder whether the performance gap mentioned above is still true for startups born after the world’s financial crisis.

We develop our analysis in the Italian context in which law 221/2012 (known as Italy’s Startup Act) has been introduced with the purpose to provide a favourable environment for the establishment and growth of innovative businesses. Since the latter must be registered in a special section of the Company Register, we had the opportunity to gather information about governance and financial data from a selected universe where businesses ought to be characterised by a high innovative and technological value. In detail, most of those female entrepreneurs work in knowledge-intensive business services, such as software production, scientific research, and other professional and technical services. In the past, all these activities have been a “male domain”.

Our findings show that, even in Italy, female startups account for only 12% of the whole selected population. However, looking at the aspects taken simultaneously as a proxy of success (size, profitability, operational efficiency, and financial management), our results reveal that innovative female-led startups have similar performances to those of their male counterparts.

Therefore, we deem that a benchmark population should be used to study this phenomenon more thoroughly to find out about new female governance styles. This understanding can help not only female entrepreneurs, but also policymakers, when allocating resources to encourage innovation and educators and when training entrepreneurs to enhance the competitiveness and sustainability of their new ventures.

The paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, a brief review of the relevant literature is presented. Section 3 details the methodology, and Section 4 and Section 5 summarise the findings of our preliminary analysis. Finally, Section 6 provides a research agenda for more in-depth investigation in the future.

2. Literature Review

Literature regarding entrepreneurship is particularly interested in explaining the drivers of entrepreneurial success (Song et al. 2008; Ayala and Manzano 2014; Boyer and Blazy 2014), and how women and men business owners perceive success (Kirkwood 2016). When considering the gender variable, the bulk of the extant research generally assumes that female entrepreneurship is less successful than male entrepreneurship (Du Rietz and Henrekson 2000; Fairlie and Robb 2009; Klapper and Parker 2010; more recently, see Brixiová and Kangoye 2016; Shinnar et al. 2018). However emerging research is challenging the so called “female underperformance hypothesis” (Robb and Watson 2012; Zolin et al. 2013; Justo et al. 2015; Aidis and Weeks 2016; Farhat and Mijid 2016).

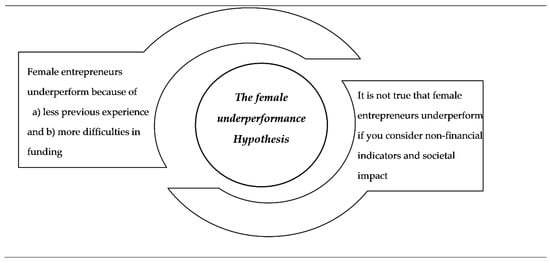

In the following section, two diverging streams of research on female business performances will be analysed (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The academic debate on the “female underperformance hypothesis”.

2.1. Research Supporting the “Female Underperformance Hypothesis”

Some studies have shown that women-owned businesses have a lower ability to achieve success and lower survival rates, sales, profits, and employees (Kalleberg and Leicht 1991; Rosa et al. 1996; Du Rietz and Henrekson 2000; Robb and Wolken 2002; Fairlie and Robb 2009).

In particular, focusing on the empirical evidence of Fairlie and Robb’s study (2009), which is one of the most quoted, business success is evaluated by simultaneously taking into consideration three different proxy variables, which are:

- The closure rate, expressed by the exit rate of companies from the market;

- the company size, expressed in terms of sales volumes and average number of employees; and

- profitability, expressed by the company’s ability to generate profits.

The analysed sample consists of companies whose performance refers to the period, 1992–1996. Information on the characteristics of business owners has been gathered by the U.S. Census Bureau. The differences between the two universes are evident:

- Female companies have lower survival rates than male companies: The average probability of closure between 1992 and 1996 is 24.4% for female-owned businesses and 21.6% for male companies;

- women-owned businesses tend to be smaller. In fact, they have sales roughly 80% lower than the average sales of male-owned firms; and

- finally, only 17.3% of female businesses have a fiscal year profit of at least US $10,000, compared to 36.4% of male companies.

From the analyses conducted by Fairlie and Robb (2009), the main factors explaining the diversity of performance between the two business universes emerge: (a) Previous work experience of the founders; (b) the level of education of the entrepreneurs; and (c) the amount of the initial capital.

Starting from the first, previous work experience of the entrepreneurs is a fundamental element, which can be associated with companies with better performances. Previous work experiences, in fact, increase human capital, in terms of skills and knowledge (Lentz and Laband 1990, Fairlie and Robb 2007), a useful tool for obtaining better business results. Concerning skills and knowledge, the issue of the level of education cannot be overlooked; the higher the level of education of the entrepreneurs, in fact, translates into better business results (Bates 1997; Åstebro and Bernhardt 2003; Headd 2003). As far as human capital is concerned, gender-based differences in newborn businesses also emerge in other studies. In fact, whereas male entrepreneurs leverage their industry and occupational background, women tend to leverage general human capital based on education and employment opportunities (BarNir 2012).

The last factor listed above, the total amount of initial capital, becomes relevant since the best performance is associated with businesses that are launched with the highest amount of startup capital (Bates 1997; Headd 2003; Coleman and Robb 2009; Robb and Coleman 2010). In their analysis, Fairlie and Robb (2009) consistently found that female entrepreneurs start their activities with less capital, in terms of both equity and loans, than men, which also explains the worst performances of female-owned businesses.

Although they are not able to verify it in their statistical analyses, the authors conclude by stating that other variables could explain the differences in gender performance. Among these are different objectives that women entrepreneurs pursue, which may have implications for business outcomes, different motivations and reasons to launch a new venture (Kourilsky and Walstad 1998; Blanchflower et al. 2001), and a different attitude towards risk (Bird and Brush 2002; Watson and Robinson 2003; Maxfield et al. 2010).

2.2. Research Challenging the “Female Underperformance Hypothesis”

In recent years, the number of scholars that challenge the “female underperformance hypothesis” has grown. Some authors, such as Robb and Watson (2012), suggested size adjusted performance measures, knowing that female-owned firms tend to be smaller than their male counterparts. Farhat and Mijid (2016) employed a matched sample approach to determine whether there is a gap in success, between male- and female-owned businesses. Based on their analysis of survival rate, profitability, growth, and financial capital injection measurement, they did not detect any gender gaps in terms of business performance.

There is also another school of thought of authors who believe that it is not true that women are less successful. Their studies are not based on statistical analysis disavowing previous results. The underpinning idea is that conventional indicators that measure the firm’s success/failure (such as the rate of closure/survival) are not grasping the specificities of women’s businesses. This is true for two reasons.

Some authors argue that it is necessary to introduce new, more expressive indicators of the real impact of female entrepreneurship. Following Aidis and Weeks (2016), high-impact female entrepreneurship is defined as firms headed by women that are market-expanding, export-oriented, and innovative, and whose assessment is focused on new indices, such as the Gender-Global Entrepreneurship and Development Index (GEDI 2018).

Other authors, instead, drawing on feminist theories (Ahl 2006; Ahl and Marlow 2012), suggest a new perspective to understand the statistical evidence. As an example, Justo et al. (2015) reject the female underperformance hypothesis by challenging the assumption that female-owned startups are more likely to fail. They argue that female entrepreneurs are actually more likely than male entrepreneurs to exit voluntarily for personal reasons and other professional/financial opportunities. This shows that the same indicators used in previous research can be interpreted differently, in light of the personal goals of entrepreneurs and how they perceive success. For example, Cliff (1998) shows that because women are more concerned about the quality of interpersonal relationships as a measure of business success than about quantitative indicators, they give a lower value to business growth than males.

Our empirical research develops from this debate and aims to challenge the gender underperformance hypothesis by analysing the financial performance of a sample of innovative Italian, female and male startups, thanks to the possibility of consulting an archive established by law since 2012 (known as Italy’s Startup Act). Compared to previous surveys, our study contributes to previous literature by focusing on technology-based ventures.

3. Methodology

The goal of our empirical research is to evaluate the performance of a selected female and male innovative startup sample, by analysing some key indicators based on the Fairlie and Robb’s (2009) proxy of “business success”, which allow us to confirm or refute the results of previous studies.

3.1. The Sample Selection

The sample selection is the result of the combined and simultaneous adoption of two databases: The Italian Company Register, in which there is a specific section for innovative startups, also with information related to the gender characteristics of their governance; and the AIDA database (https://aida.bvdinfo.com/), which contains financial data for a wide range of Italian limited liability companies.

As of February 2018, there were above 8,500 innovative startups registered in the special section of the Company Register. These companies must, among others, meet the following requirements:

- Have their headquarters in Italy or other EU countries, but with at least one production site branch in Italy; and

- produce, develop, and commercialise innovative goods or services of high technological value (See Appendix A for detailed characteristics).

As of 30 June, 2018 the AIDA database has contained 3352 innovative startups, which were subsequently subject to filters relating the date of establishment and availability of the financial statements for at least two financial years, in order to have a sample consistent with our research purposes.

The first filter related to the date of establishment provides for the selection of all the innovative startups registered between January 2012 (the year of introduction of the Startup Act) and December 2016. From the application of this first filter, the number of startups fell to 750.

The second filter concerns the availability of financial statements. Its application was necessary since not all the companies contained in the database publish their financial reporting. Consequently, the sample number fell further to 248 innovative startups.

With the application of the third filter, the need was to have financial data available for at least two years, so that financial reporting could demonstrate a running company. From the application of this third filter, the sample was made up of 227 innovative startups (see Table 1).

Table 1.

The sample selection process.

After selecting 226 innovative startups, male and female businesses were identified, thanks to the gender codification of the startups’ governance (see Appendix B for code details).

By applying this additional filter, three sub-samples of companies have been identified: exclusively or predominantly male or female companies and mixed companies, whose size is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Our sample of innovative startups by gender governance.

Fifty-eight percent of our sample consists of companies led exclusively or predominantly by men and only 12% by women. There are 30% of companies in which governance can be defined as mixed. However, the percentage of female governance companies in our sample is very close to that of the entire population of innovative Italian startups. In fact, as of February 2018, Demartini and Marchegiani (2018) found that businesses where women have an exclusive, min, or high influence on corporate governance account for 13.14% of the universe.

3.2. Data Gathering

We polarised our analyses on firms exclusively or predominantly run by men or women. Therefore, we focused on two samples made of 26 female and 131 male businesses.

To analyse the success of the innovative startups, financial ratios were obtained from the AIDA database, which contains the financial statements of the Italian startups. When looking at the two samples, we conducted a financial analysis by focusing on the income statements and balance sheets, and cash flow statements. Data refer to the financial reporting of the fiscal year of 2016 as not all companies had already filed the 2017 financial statements.

3.3. Data Analysis

We aimed not only to compare our findings with previous descriptive statistics (see Table 3), but also to express a more comprehensive assessment of the management performance. For the last reason, a complementary financial analysis is conducted on the two aggregates of companies (see Table 4). As is well known, a financial analysis is used to analyze whether an entity is profitable, stable, and solvent (Higgins 2012).

Table 3.

Business outcomes.

Table 4.

Other variables.

To compare our evidence with Fairlie and Robb (2009, p. 377), the following key indicators were collected as proxy variables of business success:

- -

- Closure rate: Measured by the number of companies no longer operating;

- -

- Size: Measured by number of employees and annual sales turnover;

- -

- Profitability: measured by EBITDA/sales.

As far as profitability is concerned, it should be highlighted that while Fairlie and Robb (2009) focused on net income, the main ratio we took into consideration was EBITDA/Sales. The latter indicator is more suitable to effectively express the profitability of a startup that may not yet have reached the break-even point, being still in a launch or development phase.

Generally speaking, it is very difficult for analysts valuing early-stage deals. The difficulty lies in the fact that relatively little or even no hard historical data exists with which an investor could make an informed decision about the company’s future prospects. Quantitative modelling runs into serious obstacles here; past successes are not necessarily an indication of future performance. EBITDA can be used to analyze and compare profitability between companies and industries because it eliminates the effects of financing and accounting decisions. In practice, value is often expressed as a multiple of some cash flow measure, e.g., enterprise value in relation to EBITDA.

To complement the previous analysis, we also focused on the following aspects:

- -

- Operational Efficiency: Efficiency is assessed through the turnover ratios (assets turnover and working capital turnover ratios) and the productivity indicators (revenues per employee, value added per employee);

- -

- Financial structure: Assessed through measurement of total equity; total liability and equity; leverage ratio.; and

- -

- Financial management: Analysed through the liquidity ratio, current ratio, and interest expenses to revenues.

Our aim is not only to verify the total amount of financial resources that the female entrepreneurs are able to collect, but also their ability both to manage it and mitigate the risks of financial embarrassment.

A list of the main financial indicators is included in Appendix C.

4. Results

In the following section, we will present our results. The analysis was carried out concerning the two sub-samples through the measurement of the average values of the key selected indicators (calculated as the sum of the values of the indicators of the individual companies divided by the number of observations).

4.1. Closure Rate

Only two companies belonging to the male universe presented a critical financial situation in the chosen period (2012–2017), liquidation, with the consequence that these were eliminated from the analysed sample.

4.2. Size

According to the average indicators shown in Table 5, it is worthwhile to notice that female companies do not present a dimensional profile significantly different from that of male companies.

Table 5.

Average company size.

4.3. Profitability

Before moving on to a detailed analysis of the ratios, we begin by declaring that there are no profound differences in terms of profitability between the two samples, although female startups show slightly better results (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Profitability.

The average percentage values of EBITDA/sales show that female companies have greater profitability than male ones (3.33% vs. 0.68%), contrary to what was stated in the previous literature.

4.4. Operational Efficiency

Regarding company efficiency, the analysis of the indicators reported in Table 7 shows that women’s businesses are even more efficient than men’s.

Table 7.

Operational efficiency.

In fact, women’s startups disclose, on average, higher revenues per employee (+11.1%) (but a lower added value per employee, −4.6%). Also, the turnover ratios express a greater pace of the female enterprises to renew their assets through business revenues.

4.5. Financial Structure

The first objective of our analysis was to understand whether female businesses are characterised by greater difficulty in raising capital, as suggested by the previous literature. In the analysis of the financial statements, these difficulties were revealed by lower levels of equity and total sources of funding, or by a higher cost of debt capital applied to women entrepreneurs.

To this end, the following indicators, including total equity and total liabilities and owner’s equity, were taken into consideration. Findings confirmed, even for our sample, that female businesses raise, on average, a lower amount of financial resources in comparison to men (−6.9%).

To complete the picture of the companies’ financial structure, the leverage ratio (calculated as the total assets divided by total equity) was equal to 22 for female startups and 10.14 for men, shows a lower capitalisation of female companies. Therefore, the female startups of our sample, despite having a smaller amount of financial resources in general, are overall more indebted and therefore make more substantial use of leverage (see Table 8).

Table 8.

Financial structure.

4.6. Financial Management

The data at our disposal did not allow us to calculate the company’s cost of money, but we can highlight that female businesses have a lower incidence of interest expenses on revenues (0.88% vs. 1.02%). Finally, the liquidity and current ratios were taken into consideration. Regarding these two, the two samples present a very similar ability to manage liquidity (see Table 9).

Table 9.

Financial management.

5. Discussion

Our findings reveal that as far as financial performance is concerned, innovative female-led startups do not lag behind male ones in terms of dimension, company profitability, efficiency, and financial management. Thus, the underperformance hypothesis is not confirmed. However, on average, female-led startups have less of owners’ equity and funds.

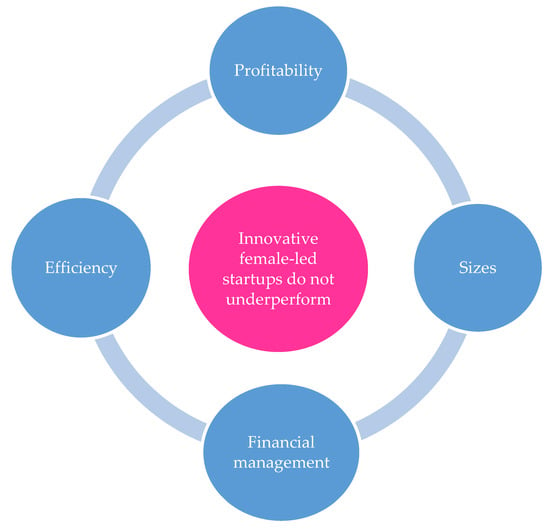

In detail, our sample of innovative female-led startups does not reflect the characteristics that have emerged from previous research (Fairlie and Robb 2009), according to which female businesses are smaller than male ones, perform less on the market, and have less stable financial standings (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Testing the underperformance hypothesis. Our findings.

However, the peculiarity of our sample, which is formed by innovative new ventures, many of which operate in the knowledge-intensive business service sector, should be emphasised. It is, therefore, possible to hypothesise that the non-confirmation of the underperformance hypothesis is strongly correlated with the characteristics of the sector and the type of services offered by the companies. Indeed, we deem that where competence and knowledge are factors on which to build the company value proposition, the gender variable does not have an impact on business performance.

In the following, each variable will be discussed.

Starting with average company size, we have found that the dimension of women’s businesses concerning sales and numbers of employees is comparable to that of men’s businesses. Therefore, in our sample, the size gap, as stated in the previous literature, is not shown.

As far as corporate profitability is concerned, contrary to what was stated in the previous literature, female companies are not less profitable than male-owned businesses. Even in terms of efficiency, female companies showed even better results concerning both the revenues per employee (proxy of market effectiveness) and capital turnover (proxy of asset management efficiency).

Regarding financial capital, we have discovered that total equity is, on average, lower in women’s businesses (confirming the analysis of Fairlie and Robb 2009). It is also true that female startups have less total liabilities and owners’ capital than male startups. At the same time, it should be emphasised that female startups show, in general, efficient financial management regarding liquidity management and the incidence of interest expenses on revenues.

6. Conclusions, Implications and Future Research

Our study aimed to answer the question of whether the innovative female-led startups, founded in recent years, underperformed in comparison to the male ones. This is one of the first exploratory studies allowing us to shed light on an emerging phenomenon concerning the spur of new technology-based ventures.

Previous studies have proven women’s businesses to be less successful. However, these analyses were carried out regarding data dating back to before 2000, and not to a sample of innovative companies.

With our study, we do not confirm this hypothesis, and indeed, our findings reveal a slightly better management efficiency in the female aggregate. However, it has been confirmed that, on average, female entrepreneurs raise less equity and sources of funding than men.

As far as the limits of our financial analyses are concerned, it should be noted that the conclusions reached in this research are based on the descriptive analysis of average indicators referring to fiscal year of 2016, and as fully explained in the previous paragraphs, reflect the characteristics of the selected companies. Our results, therefore, offer food for thought, but cannot be extended to the universe of innovative Italian startups, nor to other contexts.

6.1. Implications and Future Research

Traditional models are not always able to account for new phenomena. Thus, we deem that it is important for scholars to concentrate on applied research to develop new frameworks.

Regarding female entrepreneurship, we advocate that it could be important to understand the role of gender, in particular about new technology and business opportunities, especially in the knowledge intensive business service sector, ranging from artificial intelligence to big data management, and social media.

It could be worthwhile to analyse new business models and the impact of new technologies from a gender perspective both from the point of view of women as consumers, workers, and as entrepreneurs (UNCTAD 2014; Cesaroni et al. 2017).

We deem that future research should extend the assessment of female business performance outside the mainstream field of financial analysis and consider non-financial information and indicators referring to:

- -

- Individual and personal wellbeing; and

- -

- societal impact (about social performance, see Ebrahim and Kasturi Rangan 2014)

Thus far, literature is more prolific on the relationships between women on boards and corporate social responsibility (Bear et al. 2010). A famous professional report (Startup Genome 2018) tackled the issue in its latest survey looking at how female and male founders might differ as far as their goals are concerned. Unsurprisingly, women are more likely to be oriented toward goals with a societal impact than men. In fact, they say they want to “change the world” with their startups, while men seem to be more market-oriented and more likely to say their main mission is to “build high-quality products.” (Startup Genome 2018, p. 41).

We are aware that a statistical analysis can be useful to describe a phenomenon, but not to answer questions regarding how women run a business. We are now considering whether we can talk about an emerging female management style based on flexibility, creativity, and resilience.

To answer that last question, a qualitative and interdisciplinary analysis is needed to study women’s leadership and decision-making behaviours when running an innovative startup. In a previous exploratory survey (Demartini and Marchegiani 2018), some recurring features emerged in the management of these companies, which seem to us to be the critical success factors for their growth:

- -

- Entrepreneurs with advanced knowledge and expertise achieved mainly in their high school educational path;

- -

- a participatory leadership that fosters integrated thinking and participatory processes of co-creation; and

- -

- a strong focus on personal relationships and networking as an added value of the business model.

These aspects are worthy of being highlighted and deeply investigated in future research, with special regard to successful female startups as benchmarking case studies. They could provide useful evidence for policymakers, public, private, and not for profit organisations and individuals (i.e., business angel, professionals, academics) that are interested in fostering female entrepreneurship.

Supporting female entrepreneurship is undoubtedly a useful element for sustainable growth, not only because of the economic benefit that can derive from the growth of female entrepreneurship but also because it could be a fundamental component for cultural growth, which is essential for achieving gender equality.

We envisage the following areas of improvements to support women-led innovative startups:

- -

- Adequate funding;

- -

- incentives to foster young women’s education in disciplines of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM); and

- -

- actions to let people know they can learn from successful models of high tech female entrepreneurs.

6.2. Funding

Venture capital and business angel financing have traditionally been advocated as important sources of financing for young innovative firms that find it difficult to access bank or debt finance. Moreover, the landscape for entrepreneurial finance has changed over the last years. Several new actors have emerged (i.e., crowdfunding, government-sponsored funds, etc.) and some of these new players value not only financial goals, but are also interested in non-financial goals (i.e., technological and community-based goals). Our research revealed that women’s new businesses are even more efficient than men’s and that female entrepreneurs are more likely to be oriented toward goals with a societal impact than male ones. For the above-mentioned reasons, we deem that investors should be aware of the potentiality that female led-startups own.

6.3. Young Women Education

Furthermore, we suggest that more action is needed that aims to bridge the gender gap in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). This research could be successful to promote scientific and technical training for girls and raise the debate on new digital skills needed to create new high tech ventures.

6.4. Successful Models of High Tech Female Entrepreneurs

Finally, we deem that through inspirational keynote speakers, personal development workshops, technical classes, and networking opportunities, women in technology can connect, learn, and act on gender diversity by sharing the experiences of industry leaders and developing women’s skills, both soft and technical.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Italy’s startup Act.

Table A1.

Italy’s startup Act.

| Definition and Characteristics of Innovative Italian Startups by Law 221/2012 |

|---|

Innovative startups are companies with shared capital (i.e., limited companies), including cooperatives, the shares or significant registered capital shares of which are not listed on a regulated market nor on a multilateral negotiation system. These companies must also meet the following requirements:

|

Appendix B

Table A2.

Italian innovative startups. Classification by gender governance.

Table A2.

Italian innovative startups. Classification by gender governance.

| % Owners and Directors’ Gender | Governance Classification |

|---|---|

| X = 100% | Exclusively Male or Female |

| X > 66% ˅ X < 99% | Predominately Male or Female |

| X > 51% ˅ X < 66% | Mixed Male/Female |

Source: Italian Company Register.

Appendix C

List of main financial indicators

- EBITDA is the acronym for Earnings before Interests, Tax, Depreciation and Amortisation.

- The Total Assets Turnover Ratio is calculated as follows: net sales or revenue divided by the average total assets during the same 12 month period. It can often be used as an indicator of the efficiency with which a company is deploying its assets in generating revenue.

- The working capital turnover ratio is calculated as follows: net annual sales or revenue divided by the average amount of working capital during the same 12 month period. It indicates a company’s effectiveness in using its working capital.

- Leverage ratio (times) compares equity to assets and is calculated as total assets divided by total equity. A high ratio indicates that the business owners may not be providing sufficient equity to fund a business.

- Liquidity (quick) ratio is calculated as follows: (Cash equivalents + marketable securities + accounts receivable) divided by current liabilities.

- The current ratio is calculated as follows: Current assets divided by current liabilities

- Interest expense to revenue ratio = Total interest expenses divided by total revenues

References

- Ahl, Helene, and Susan Marlow. 2012. Exploring the dynamics of gender, feminism and entrepreneurship: Advancing debate to escape a dead end? Organization 19: 543–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahl, Helene. 2006. Why research on women entrepreneurs needs new directions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 30: 595–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidis, Ruta, and Julie Weeks. 2016. Mapping the gendered ecosystem: The evolution of measurement tools for comparative high-impact female entrepreneur development. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship 8: 330–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, Howard. 1989. Networking among women entrepreneurs. Women-Owned Businesses 103: 132. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, Sharon A., and Lowell W. Busenitz. 2001. The entrepreneurship of resource-based theory. Journal of management 27: 755–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åstebro, Thomas, and Irwin Bernhardt. 2003. Start-up financing, owner characteristics, and survival. Journal of Economics and Business 55: 303–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, Erkko, Robert H. Keeley, Magnus Klofsten, and Thomas Ulfstedt. 1997. Entrepreneurial intent among students: Testing an intent model in Asia, Scandinavia and USA. In Proceedings of the Seventeenth Annual Entrepreneurship Research Conference. Wellesley: Babson College, pp. 133–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala, Juan-Carlos, and Guadalupe Manzano. 2014. The resilience of the entrepreneur. Influence on the success of the business. A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Economic Psychology 42: 126–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BarNir, Anat. 2012. Starting technologically innovative ventures: Reasons, human capital, and gender. Management Decision 50: 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, Timothy. 1997. Financing small business creation: The case of Chinese and Korean immigrant entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing 12: 109–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bear, Stephen, Noushi Rahman, and Corinne Post. 2010. The impact of board diversity and gender composition on corporate social responsibility and firm reputation. Journal of Business Ethics 97: 207–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beede, David N., Tiffany A. Julian, David Langdon, George McKittrick, Beethika Khan, and Mark E. Doms. 2011. Women in STEM: A gender gap to innovation. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Elisabeth S. C., and Andreas Kuckertz. 2016. Female entrepreneurship in startup ecosystems worldwide. Journal of Business Research 69: 5163–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, Barbara, and Candida Brush. 2002. A gendered perspective on organizational creation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 26: 41–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchflower, David G., Andrew Oswald, and Alois Stutzer. 2001. Latent entrepreneurship across nations. European Economic Review 45: 680–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, Joern H., Christian O. Fisch, and Mirjam Van Praag. 2017. The Schumpeterian entrepreneur: A review of the empirical evidence on the antecedents, behaviour and consequences of innovative entrepreneurship. Industry and Innovation 24: 61–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, Tristan, and Régis Blazy. 2014. Born to be alive? The survival of innovative and non-innovative French micro-start-ups. Small Business Economics 42: 669–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brixiová, Zuzana, and Thierry Kangoye. 2016. Gender and constraints to entrepreneurship in Africa: New evidence from Swaziland. Journal of Business Venturing Insights 5: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, Candida G., Anne De Bruin, and Friederike Welter. 2009. A gender-aware framework for women’s entrepreneurship. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship 1: 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesaroni, Francesca M., Paola Demartini, and Paola Paoloni. 2017. Women in business and social media: Implications for female entrepreneurship in emerging countries. African Journal of Business Management 11: 316–326. [Google Scholar]

- Cliff, Jennifer E. 1998. Does one size fit all? Exploring the relationship between attitudes towards growth, gender, and business size. Journal of Business Venturing 13: 523–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, Susan, and Alicia Robb. 2009. A comparison of new firm financing by gender: Evidence from the Kauffman Firm Survey data. Small Business Economics 33: 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demartini, Paola, and Lucia Marchegiani. 2018. Born to Be Alive? Female Entrepreneurship and Innovative Start-Ups. In IPAZIA Workshop on Gender Issues. Cham: Springer, pp. 219–35. [Google Scholar]

- Demartini, Paola, and Paola Paoloni. 2014. Defining the entrepreneurial capital construct. Chinese Business Review 13: 668–80. [Google Scholar]

- Du Rietz, Anita, and Magnus Henrekson. 2000. Testing the female underperformance hypothesis. Small Business Economics 14: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, Alnoor, and V. Kasturi Rangan. 2014. What impact? A framework for measuring the scale and scope of social performance. California Management Review 56: 118–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, Truls. 2002. Entrepreneurial capital: The emerging venture’s most important asset and competitive advantage. Journal of Business Venturing 17: 275–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairlie, Robert W., and Alicia M. Robb. 2009. Gender differences in business performance: Evidence from the Characteristics of Business Owners survey. Small Business Economics 33: 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairlie, Robert W., and Alicia Robb. 2007. Families, human capital, and small business: Evidence from the characteristics of business owners survey. ILR Review 60: 225–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, Joseph, and Naranchimeg Mijid. 2016. Do women lag behind men? A matched-sample analysis of the dynamics of gender gaps. Journal of Economics and Finance, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatewood, Elizabeth J., Candida G. Brush, Nancy M. Carter, Patricia G. Greene, and Myra M. Hart, eds. 2003. Women Entrepreneurs, Their Ventures, and the Venture Capital Industry: An Annotated Bibliography. Stockholm: Entrepreneurship and Small Business Research Institute (ESBRI). [Google Scholar]

- Gatewood, Elizabeth J., Candida G. Brush, Nancy M. Carter, Patricia G. Greene, and Myra M. Hart. 2009. Diana: A symbol of women entrepreneurs’ hunt for knowledge, money, and the rewards of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics 32: 129–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GEDI. 2018. Available online: https://thegedi.org/research/womens-entrepreneurship-index/ (accessed on 17 November 2018).

- Harris, Christine R., and Michael Jenkins. 2006. Gender differences in risk assessment: Why do women take fewer risks than men? Judgment and Decision Making 1: 48–63. [Google Scholar]

- He, Xin, J. Jeffrey Inman, and Vikas Mittal. 2008. Gender jeopardy in financial risk taking. Journal of Marketing Research 45: 414–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headd, Brian. 2003. Redefining business success: Distinguishing between closure and failure. Small Business Economics 21: 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, Robert C. 2012. Analysis for Financial Management. New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, Karen D., Jennifer E. Jennings, Candida Brush, Sara Carter, and Friederike Welter. 2012. Extending women’s entrepreneurship research in new directions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 36: 429–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, Jennifer E., and Candida G. Brush. 2013. Research on women entrepreneurs: Challenges to (and from) the broader entrepreneurship literature? The Academy of Management Annals 7: 663–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justo, Rachida, Dawn R. DeTienne, and Philipp Sieger. 2015. Failure or voluntary exit? Reassessing the female underperformance hypothesis. Journal of Business Venturing 30: 775–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalleberg, Arne L., and Kevin T. Leicht. 1991. Gender and organizational performance: Determinants of small business survival and success. Academy of Management Journal 34: 136–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood, Jodyanne Jane. 2016. How women and men business owners perceive success. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 22: 594–615. [Google Scholar]

- Klapper, Leora F., and Simon C. Parker. 2010. Gender and the business environment for new firm creation. The World Bank Research Observer 26: 237–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourilsky, Marilyn L., and William B. Walstad. 1998. Entrepreneurship and female youth: Knowledge, attitudes, gender differences, and educational practices. Journal of Business Venturing 13: 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuschel, Katherina, and María-Teresa Lepeley. 2016. Women start-ups in technology: Literature review and research agenda to improve participation. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business 27: 333–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentz, Bernard F., and David N. Laband. 1990. Entrepreneurial success and occupational inheritance among proprietors. Canadian Journal of Economics 23: 563–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxfield, Sylvia, Mary Shapiro, Vipin Gupta, and Susan Hass. 2010. Gender and risk: Women, risk taking and risk aversion. Gender in Management: An International Journal 25: 586–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, Alicia M., and John Watson. 2012. Gender differences in firm performance: Evidence from new ventures in the United States. Journal of Business Venturing 27: 544–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, Alicia M., and Susan Coleman. 2010. Financing strategies of new technology-based firms: A comparison of women-and men-owned firms. Journal of Technology Management & Innovation 5: 30–50. [Google Scholar]

- Robb, Alicia, and John Wolken. 2002. Firm, owner, and financing characteristics: Differences between female-and male-owned small businesses. FEDS Working Paper No. 2002-18. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=306800 (accessed on 17 November 2018).

- Rosa, Peter, Sara Carter, and Daphne Hamilton. 1996. Gender as a determinant of small business performance: Insights from a British study. Small Business Economics 8: 463–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinnar, Rachel S., Dan K. Hsu, Benjamin C. Powell, and Haibo Zhou. 2018. Entrepreneurial intentions and start-ups: Are women or men more likely to enact their intentions? International Small Business Journal 36: 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Michael, Ksenia Podoynitsyna, Hans Van Der Bij, and Johannes I. M. Halman. 2008. Success factors in new ventures: A meta-analysis. Journal of Product Innovation Management 25: 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Startup Genome. 2018. Global Startup Ecosystem Report 2018. Available online: https://startupgenome.com/reports/2018/GSER-2018-v1.1.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2018).

- UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development). 2014. Empowering Women Entrepreneurs through Information and Communications Technologies: A Practical Guide. UNCTAD/DTL/STICT/2013/2. New York and Geneva: United Nations publication. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, John, and Sherry Robinson. 2003. Adjusting for risk in comparing the performances of male-and female-controlled SMEs. Journal of Business Venturing 18: 773–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolin, Roxanne, Michael Stuetzer, and John Watson. 2013. Challenging the female underperformance hypothesis. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship 5: 116–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).