Abstract

Over the past few decades, many governments throughout the world have promoted gender-responsive budgeting (GRB). With its focus on equality, accountability, transparency and participation in the policy-making process, GRB shares some relevant principles with public governance that call governments at national and subnational levels to rethink their roles in the whole economic system. This worldwide political and managerial interest does not find sufficient space in academic discussion, mainly in terms of public administration and management studies. Adopting an interpretative approach, the present study aims to investigate how an Italian municipality has involved stakeholders in the GRB process. The case study shows that, when GRB is fully developed, the stakeholders involved are both internal and external, and these multiple actors, in pursuing gender equality, cooperate to achieve a common, public aim. In this way, GRB gives effectiveness to the public decision-making process, contributing to greater incisiveness in the local government’s management and creation of a gender-sensitive governance process.

1. Introduction

Over the past few decades, many governments throughout the world have promoted initiatives to advance gender equality (Budlender 2002). More recently, European institutions have included gender topics among the European strategies for sustainable development, together with the fight against poverty and social exclusion (Council of the European Union 2006).

Owing to the predominance of economic criteria in policy design, one of the goals of gender initiatives is to criticise the neutrality of public budgets (i.e., the gender blindness of budgets, Elson (1998)), which ignore the differing impacts of revenues and expenditures on men and women because of their divergent gender roles in society (Elson 1999).

Thus, the expression “women’s budget” (Budlender 2000) and, in recent times, gender-responsive budgeting (GRB), denote a national or local government budget that integrates the gender perspective into all phases of the budget cycle. The GRB aims to foster greater gender equality, efficiency and effectiveness, as well as transparency, accountability and the participation of civil society in the budget decision-making process.

Accordingly, in the gender framework, citizens are both beneficiaries and agents of the process whereby governments, at all levels, redesign their policy-making mechanisms and their accountability systems. As the GRB involves stakeholders and ensures that policy design and the allocation of resources meet the wide variety of citizens’ needs, it must be considered as an important tool of public governance (Brody 2009).

Nevertheless, GRB is under-investigated in the public administration and management streams of literature. As Rubin and Bartle (2005, p. 260) have pointed out, “almost all of the research related to gender-responsive budgeting has taken a normative approach, promoting its use as a way to advance gender equality”. While the authors examined “the potential of GRB for budget reform, following a long line of efforts to effectuate changes in the budget decision-making process” (Rubin and Bartle 2005, p. 260), the present study aims to investigate how the adoption of the GRB affects public governance and management through stakeholder engagement, in the awareness that “critical to the success of gender-responsive budgeting is the buy-in of stakeholders inside and outside government” (Rubin and Bartle 2005, p. 269).

The empirical focus of the paper is the municipality of Bologna, which introduced a GRB in 2008, incorporating the gender perspective into the planning stage of the budget cycle. The study sheds light on the enhancement of stakeholder engagement throughout the entire GRB process.

This paper contributes to the extant literature in three ways. First, it emphasises the GRB as a public governance tool with an in-depth case study. Second, it employs the stakeholder engagement strategy as a framework to investigate how GRB may enhance the participation of various stakeholders for the equal allocation of resources dedicated to men and women. Third, it highlights the way in which stakeholder participation in the GRB practices promotes the accountability of decision-making mechanisms in public domains. The study contributes to the present Special Issue by supporting the idea that the adoption of a stakeholder engagement strategy in forwarding GRB could enhance gender equality policy promoted by both public and private organisations, and addressing the challenges of diversity and gender inequalities.

The article is structured as follows: The second section illustrates the review of literature and the third one presents the conceptual framework used for the case study analysis; the fourth section regards methodology; the fifth section examines empirics from the case study; the sixth section is dedicated to the discussion of the results; and the seventh section proposes some concluding remarks.

2. Literature Review: Gender Equality, Gender-Responsive Budgeting, and Stakeholder Involvement

Gender equality is a long-established priority for the entire world. Since 1957, when The Treaty of Rome incorporated the right of men and women to equal pay for equal work, and since 1979, when the UN General Assembly adopted the Convention on the Elimination of All the Forms of Discrimination against Women, international agencies and national governments have committed themselves to advancing gender equality.

In 1995, the Fourth World Conference on Women, held in Beijing (Beijing Platform for Action 1995), called for governments to incorporate the perspective of gender equality at all stages and all levels of public policy-making, including the budgetary processes. Thus, GRB requires that the gender perspective be considered in every phase of budgetary decisions and in the drawing up of budgets. Before this awareness, different concepts (“women’s budgets”, “women’s budget statements”, “gender-sensitive budgets”, “gender-responsive budgets” and “gender budget analysis”) were used to describe the process of integration between gender and public budgets. Aiming to integrate gender into the decision-making process regarding expenditures and revenues, GRB indicates a government budget (at both national and local levels) (Council of Europe 2005) that incorporates a gender perspective in any or all parts of its process, in order to improve gender equality among its community (Budlender et al. 2002; Budlender and Hewitt 2002, 2003; Sharp 2002, 2003).

Therefore, GRB denotes a process that moves through two stages: (i) gender analysis or auditing; and (ii) gender budgeting. The former is related to the conceptual and analytical work done in order to assess the impact of budgets on different groups of women, men, girls, and boys. The latter refers to the ultimate goal of gender initiatives, namely a gender-aware formulation of the budget (Hofbauer Balmori 2003; Sharp 2002). The first stage of the process has raised awareness of gender issues and the government’s accountability in terms of its commitment to gender equality (Sharp 2002, p. 90) by devising frameworks (Elson 2002; Sharp 2003) and tools for analysis (Budlender and Hewitt 2003; Sharp 2002), guidelines to support governments in their initiatives (Budlender et al. 1998; Budlender and Hewitt 2003; Hofbauer Balmori 2003), and gender-sensitive indicators (Beck 1999; Rubery et al. 2002). Although most GRB initiatives are still at this stage of the GRB process (Budlender et al. 2002; Budlender and Hewitt 2002; Rubin and Bartle 2005), there are some instances in which gender has been introduced into planning activities as a cross-cutting criterion (Budlender 2007; Sharp and Vas Dev 2004) in an attempt “to bridge the gap between gender-sensitive budget analysis and the formulation of gender-sensitive budgets” (Hofbauer Balmori 2003, p. 45).

Gender budget exercises have been undertaken at international, national, and subnational levels of government in developed and developing countries (e.g., France, Sweden, Norway, Italy, the Netherlands, Uganda, and Tanzania), being coordinated and led by both governments (e.g., Australia and France) and civil society groups (e.g., UK, South Africa, and Tanzania) (Budlender et al. 1998, 2002). Unlike the majority of experiences worldwide, in Italy GRB is adopted by local governments, which perform a central role in regard to gender issues by designing policies, actions, and services to enhance gender equality in their communities.

Despite the governmental commitment to gender equality, there is a lack of substantial progress in reducing gender inequalities, particularly due to the predominance of economic criteria in policy design (Hofbauer Balmori 2003). In fact, macroeconomic frameworks do not consider the differences between men and women, as well as between different groups of men and women. As a result, the economic and statistical models are gender-blind, and the budget is considered to be a gender-neutral policy tool, thus ignoring the fact that a budget has a differentiated impact on men and women, because of their diverse gender roles in society (Elson 1999). Meanwhile, public budgets could be the main tools in transforming and redressing existing gender inequalities. Hence, GRB forms a specific process for advancing toward equality through the allocation of public resources.

Therefore, the main aim of the GRB process is to contest the alleged neutrality of government budgets (Elson 1998) by introducing and pursuing the goals of equality, efficiency, transparency, participation, and awareness in public economic policies. Not taking into account the differences between men and women means that the policies adopted are not neutral toward citizens.

The GRB aims to allocate resources deemed appropriate for the needs and priorities of men and women—needs and priorities that differ in nature—to allow men and women to achieve equality of outcomes from economic policies. While greater equality between men and women has been indubitably the most evident objective—and the one most frequently cited (at least initially) to justify GRB—other goals have arisen (Himmelweit 2002). The first of them is efficiency, to which governments and local authorities have grown sensitive in recent years. Because gender analysis requires knowledge of the gender differences among the population, it seeks: (i) to obtain a better use of resources, especially those, like unpaid work, not measured by economic and statistical indicators, so that there is a match between the demand expressed by the population and the supply of services by the government agency; and (ii) to show how apparently gender-neutral policy decisions have differing economic and social consequences for the male and female components of the population.

The adoption of GRB makes it possible to assess the effectiveness of economic policy measures on women and men, evaluating the consistency between outcomes achieved and pre-established objectives. In particular, adopting the gender perspective, the evaluation of effectiveness aims to verify whether the outcomes achieved by public policies meet the needs of both men and women.

The GRB highlights the link between governmental commitment toward gender equality and their responsibility to define a gender-sensitive form of collection and use of public resources (accountability). On the one hand, by pointing out the links between gender equality and efficiency and effectiveness, GRB makes institutions more aware of the consequences of their decisions on civil society, thus giving citizens a new tool to evaluate the use of public resources. On the other hand, GRB requires the involvement of civil society in the process of public policy analysis (Osborne et al. 2008).

The experience of GRB has seen an increase in the involvement of several actors (women’s associations, non-governmental organisations, and civil society in general) who have exerted pressure to see gender equality substantially recognised.

Despite its improvement, to date there is still no reference standard for GRB models and a variety of analytical tools can be used (Budlender et al. 1998; Elson 1998). In the same way, there is still no reference for which actors to involve in the process. As mentioned by Osborne et al. (2008), there is a dichotomy between “expert-bureaucratic” and ”participative-democratic” models of gender mainstreaming initiatives according to the extent to which the models incorporate strategies for community participation.

Evidence from gender initiatives worldwide (Budlender et al. 2002) demonstrates that the active involvement of many actors (experts on gender issues as well as civil society) enables GRB to be more effective (Krafchik 2002; Zuckerman 2005), i.e., to improve gender equality within society. The involvement of stakeholders also improves the transparency and accountability of the budgeting process by inducing governments to provide information on the use of public money, which is normally not available, as well as to ensure continuity of the practice, avoiding its interruption due to political change, as documented by Sharp and Broomhill (2002) in the Australian case study.

As GRB is increasingly seen as a proper tool for good governance (UNDP 1999; Elson 2006; Hewitt and Mukhopadhyay 2002; Sharp 2002), the relevance of stakeholder engagement has increased. According to academic studies on governance, the distinctive features of public governance can be summarised as follows: stakeholder involvement in the definition and implementation of public policy (Bovaird 2005; Bovaird and Löffler 2002); coordination of collaborative relations internally and externally to public administration (Elander 2002); and orientation toward the outside, which introduces the notion of the public administration’s accountability to its citizens (Meneguzzo 1997).

Dialogue among stakeholders constitutes the basis of this framework; individuals and organisations may thus exercise power over decisions concerning their interests and well-being. This continuous communication shapes rules and practices in decision-making and opens a wide debate on collective problems; a debate that was usually confined to public authorities. The engagement of stakeholders in order to change policy priorities and budgets (so as to enhance gender equality) makes it possible to locate GRB within the public governance scenario. The next section investigates this framework.

3. The Conceptual Framework

“Since the establishment of the paradigm of public governance (…), stakeholders’ mapping and engagement have become a well-established practice in policy making.” (Barreca 2012). As described in the previous section, a common feature of GRB and public governance principles is stakeholder involvement mainly during the design and implementation phases.

To understand how stakeholders engage in GRB, it is necessary to identify (map) them and determine their importance to the organisation. Some studies have identified three categories of stakeholders: interface stakeholders (board members); internal stakeholders (managers, employees); and external ones (funders, beneficiaries, suppliers, competitors, partners, and others) (Van Puyvelde et al. 2012; Savage et al. 1991). Although most studies concerning stakeholder theory have been developed in for-profit organisations, over time some authors have tried to classify various non-profit stakeholders (Ben-Ner and Van Hoomissen 1991; Bryson 2004; Van Puyvelde et al. 2012).

Adopting Freeman’s (Freeman 1984) broad definition of stakeholders, we consider them to be all groups or individuals who may affect or are affected by achievement of the public administration’s gender policy. At the same time, the definition and description of the level of engagement implicitly identify the importance of each of them. According to Pedersen (2006, p. 140), stakeholder engagement, or stakeholder dialogue (for some authors), entails “the involvement of stakeholders in the decision-making processes that concern social and environmental issues”.

GRB practices require different involvement in each phase of the implementation process. According to the models of participation described by Osborne et al. (2008), in an “expert-bureaucratic” system, probably just one group of stakeholders (who lead the process) is involved in the decision-making process. In this approach, gender experts carry out only an impact assessment of the gender implications of policies and activities. By contrast, the “participative-democratic” model entails co-participation in governance mechanisms and systems from the beginning of the process, thus incorporating the widespread consultation and participation of multiple interest groups.

Despite the presence of these different approaches, the distinction is not at all clear due to the “complexities and ambiguities of the consultation exercise” (Osborne et al. 2008). In order to clarify the participation process, Noland and Phillips (2010) identified ethical strategic engagement as a way to integrate moral involvement with a business strategy. This trend goes beyond Habermasian scholars that ensure communication uncorrupted by power differences and strategic motivations. In public organisations, business strategies are far from pursuing financial goals, although these are prerequisites for citizens’ welfare. The community is implicitly involved in local government, but participation cannot be taken for granted when the administration adopts voluntary practices. Similar practices also require the voluntary participation of stakeholders interested in gender issues. The sharing strategy assures free discussion about gender values and strategies in order to furnish sustainable welfare policies and services. Ethical strategic engagement has the same basis as a “participative-democratic” gender mainstreaming strategy.

According to frameworks (Bryson et al. 2012; Cumming 2001; Foo et al. 2011; Nabatchi 2012), stakeholder participation is not just a statement; it is also a specific process organised by the public administration. Clearly, the adoption of a practice (i.e., the GRB tool) requires a procedure that follows a change in stakeholder engagement from one-way communication (i.e., from public administration to stakeholders) to two-way communication (i.e., from/to public administration and from/to stakeholders).

Nabatchi (2012) suggests a process whose initial phase involves only communication to stakeholders on the project undertaken (i.e., the information step). The following steps involve a two-way dialogue, although the strategy, method, and timing of the process are in the public administration domain until the collaboration phase. The collaborative relationship fosters empowerment behaviours, thereby increasing the level of stakeholder confidence and responsibility concerning the entire process of implementation and its outcome.

The promotion of decentralised decision-making and participation by citizens (i.e., women and men) is not a costless process, but it ensures that policies “might be more realistically grounded in citizen preferences” (Irvin and Stansbury 2004). In GRB terms, this means that the entire community and other organisations may actively participate in the mise en oeuvre of gender policies, guaranteeing the principles of the welfare state. The existing literature underlines the complexity of the GRB incremental process, describing the audit phase and the budget phase as the opposite ends of a sort of continuum. The features of gender auditing are distant from those of a review of principles and policies; but when public administrations are willing to share ex-ante decision-making acts (i.e., the budgeting phase), this means that the auditing and budgeting phases generate an interactive cycle that increases the level of accountability.

4. Materials and Methods

Contrary to what happened in other countries, where central governments have performed the role of promoting actors, in Italy gender initiatives have been promoted at the subnational level. They therefore involve provincial administrations, municipalities, and, more rarely, regional governments (Bettio et al. 2002; Villagomez 2004).

To carry out the present study, we adopted the ground theory principles (Corbin and Strauss 1990) by first defining the phenomenon to analyse and then identify an appropriate site of research. The Italian municipality in which our study took place, Bologna, has 390,000 inhabitants, while its metropolitan area has a population of about 1 million. Bologna has a long-standing social tradition evidenced by numerous non-governmental organisations and voluntary associations working in the urban context. Therefore, it is not by chance that Bologna was the first Italian local government to produce a social report. Often, in the Italian and European context, Bologna has been a well-known entity for specific initiatives, such as in the fields of education and the elderly. As Bologna has promoted the GRB initiative since 2005, it provides distinctive evidence in the European area. In 2014, during the Forum of Public Administration supported by the Italian central government, Bologna was officially recognised as one of the well-developed gender experiences. In relation to gender issues, Bologna is undertaking both stages of the GRB process (auditing and budgeting), including these practices in regular accounting and control procedures.

Gathering data from multiple sources should allow for a deep comprehension of a phenomenon that is developed in practice but under-investigated by academia (Yin 2003). The present research began with a documentary analysis (secondary data) of official reports, policy guidelines, public statements, electronic helpdesk records, and other GRB documents available in the public domain (the local government’s website). The documentary data collection and analysis took place between October 2011 and June 2013.

The documentary analysis was useful for drawing up an interview agenda (primary data) with the key actors involved in the GRB process. Semi-structured interviews with the internal technical staff who led the project were carried out face to face, by telephone and e-mail between April and June 2013 (Kvale 1996; Morgan and Symon 2004; Hunt and McHale 2007). These interviews made it possible to gather further documents and information about the methods, strategies, and timing for the involvement of stakeholders, as well as the decisions and actions resulting from their engagement and the agenda that allowed for the implementation of gender budgeting. All the interviews have been recorded and fully transcribed.

For the interpreting process, we combined open and literature coding based on the analysis of documents, interviews, and notes. In particular: (i) each interview was read and listened to several times by each author in order to become familiar with the text and eliminate the non-relevant parts of text, and all the researchers got a sense of the whole situation from reading all the transcriptions and documents; (ii) each author listed the topics that considered the substance of the information described by the actors/documents; (iii) later, the researchers discussed this preliminary coding to compare and share their intuition and interpretation, and a joined and selected list emerged; (iv) furthermore, each author carefully read the extant literature, taking notes about topics regarding GRB features and stakeholder involvement in GRB; and finally, (v) all the researchers returned to the data, identifying the final coding to use for the analysis of the case study.

5. Results

The municipality of Bologna was the first Italian local government to issue social reporting (in 1997, see Marcuccio and Steccolini 2009), while its gender initiatives fit the track of the Gender Feasibility Study published by the Emilia Romagna Region in 2001. The mandatory programme for the years 2004–2009 emphasised gender issues as public values and incorporated gender into programme guidelines, while in 2005 the municipality published a gender feasibility study focused on services for children.

The short-term aim is to recognise that the municipality of Bologna requires a unitary process, both of steerage and organization, which adopts and implements this approach [gender mainstreaming]. This process, still entirely to be constructed, must necessarily work crosswise (…). But the introduction of gender difference policies wants to be more: it wants also to be an autonomous driver of policies and action in all fields and all activities (…), assuming and revising the traditional powers of government, administrative and managerial, in regard to difference policies, from a standpoint entirely addressed to the future and change in the life of the city.(Municipality of Bologna 2005, p. 100)

Nonetheless, only since 2008 has GRB been a stable component of the Forecasting Planning Report. Since the issue of 2008, GRB has employed the same social report matrix to reinforce the link between social sustainability reports, actions, and services with a direct or indirect impact on equality between men and women.

The adoption of the Gender Budget is addressed to the need of visibility about the impact of the distribution of resources (e.g., financial, for services, opportunities, participation, etc.) on the life-conditions and relative disadvantage of women. (…) GRB is a tool that promotes the alignment between gender policy and the local government values fostering effective and efficient actions. Moreover, the aim to make Gender Budget as a managerial ‘routine’ is part of a more general commitment to social auditing as an essential means to plan and to connect with civil society (…).(Gender Auditing Report 2008, p. 6)

From the outset, GRB has been conceived as a participatory process with the involvement of internal and external stakeholders.

The process has been characterized by close linkage with the municipality’s mandatory programme and not only procedural attention to participation by leading gender-policy players: the city executive committee and council, associations and boards.(Gender Auditing Report 2008, p. 9)

Gender auditing initiatives have been developed with the involvement of the mayor and his board, stressing the political commitment of the process. The Elected Women’s Commission and the internal staff have fostered the methodological formulation of the process and women’s associations in the city have been consulted to assess the direct and indirect impacts of public expenditures.

(…) 4. The Commission submits to the Council proposals and observations on issues with a bearing on the female condition and that may be developed into equal opportunities policies. To this end, it may consult women’s associations, community organizations, and experts with proven competence and/or professional experience.5. The Municipal Executive Committee may obtain a Commission opinion about the guidelines containing the actions addressed to the female population.(Statute of the (Municipality of Bologna 1991, art. 22) “Elected Women’s Commission”)

According to these purposes, the internal staff organised an open seminar (held on 9 November 2007) with the participation of women’s associations engaged with the Bologna Women’s Network. During the seminar, priorities were set for female issues, and the proposal was made to select a district in the city as a “laboratory” for the development of a gender budget (formal meeting notes). The observations and findings from the seminar were borne in mind; in fact, in 2010 a first attempt was made to draw up a gender budget in Bologna’s Savena district.

At the beginning of 2013, the municipal council decided to formulate a GRB for 2014, linking it with the performance management cycle in which each public institution measures and assesses its performance with regard to its organisational units and its employees, stressing internal and external accountability. Accordingly, the GRB process is developed by the Planning Department, which manages all accounting flows and statistical data, supporting the Directorate-General in the performance management cycle as well as in the participatory process at the central and suburb levels.

The Planning Department’s choice is of strategic value given its role in the management of decision-making processes on the budget, social reporting and public participation, as well as its links with the administration as a whole. Recent years have seen substantial cutbacks in the resources available to the municipality, thus raising issues, more forcefully than in the past, of how to select lines of action and to allocate resources. At the same time, the gender budget was drawn up in light of experience, incorporating the gender perspective into planning activities. According to this new scenario, the GRB approach is now a strategic tool driving the allocation of public resources, inducing the local government to redesign the GRB process and its various phases.

(…) We can’t allow this thing [the wastage of resources] to go on any longer… This is a cultural revolution … But when we take a step (…) we mustn’t lose time (…) this project should be part of a process, so it must start from the awareness of what it means to plan at municipal level, and from there make claims together, and this means work for them [associations] as well.(Electronic Interview 14 May 2013)

Consistently with the performance management cycle, the construction of the gender budget was preceded by the reclassification of all the Planning Department’s activities in accordance with the gender perspective. This reclassification significantly increases both the gender and overall accountability of the municipality in terms of the actors involved, responsibilities, resources allocated, and outcomes.

After this reclassification, the gender budgeting process involves the relevant stakeholders in the selection (“call of ideas”, Interview 21 June 2013) of the projects to be given priority in gender terms, which are then used as the basis for constructing the gender budget. The main actors involved in the process are:

- Political actors: executive committee and council, Elected Women’s Commission, including the female members of district councils;

- Technical actors: Planning Department; and

- Community actors: relevant and representative associations.

The community actors are selected from the associations enrolled in the municipal register whose statutes make specific reference to gender. Hence, unlike in the past, exclusively “female” associations are not selected; rather, in order to expand the dialogue, associations sensitive to “gender” issues (from the feminist perspective to the gender perspective) are chosen.

Associations are chosen if they have consolidated relations with the municipality in terms of financial and other resources made available to them by the latter (for instance, public premises for use by the associations). Representativeness—in terms of their capacity to impact the community—is assessed by the department heads, councillors, and the presidents of the district councils. Because they work in close contact with the associations, they are better able to assess their potential impact.

(…) we have one thousand six hundred associations working in the community, each of which does something or other (…) It’s obvious that we know which the hundred associations with important representativeness are (…) and we can also tell from the accounting figures on transfers to these associations (…) selection of the hundred important associations is also made by the department heads, the councilors who have relations with the sector, the presidents of the district councils.(Interview 21 June 2013)

This is therefore a qualitative and quantitative enlargement of the stakeholders involved. However, the change also concerns the relationship with the latter. In fact, the Planning Department required the associations to participate in the selection of projects to be included in the GRB. Moreover, the associations participated in implementing the projects selected, by contributing their own resources. Since the intent is to work concretely on the projects, the involvement concerns associations willing to establish a partnership with the municipality according to a horizontal subsidiarity approach. The head of the Planning Department argued that:

the associations must realize that they are not there to ask what we can do for them, but (…) they must play their part as well (…) The objective is to specify the extent already in the gender budgeting phase as policies are devised (…) and we expect to work together (…) and get involved, not just asking us for money (which we don’t have any more) but bringing us commitments and ideas.(Interview 21 June 2013)

This approach—profoundly different from the previous relationship—also affects the associations, because it induces them to reconsider and assess proposals to submit to the public administration in relation to their resources and priorities. This obliges them to acquire greater awareness of the gender impact of their activities by reconsidering their projects in gender terms. While for the “female” associations this process is rather natural, for all the others it entails a more profound re-thinking. In this regard, a member of the planning team said (with reference to social collectives):

I expect them to take account of gender in the planning phase (…) they should conceive their activities bearing in mind that they have differing impacts on men and women (…) they should involve the cultural point of view in their activities (…) they’d give great added value to their association and the city.(Interview 21 June 2013)

The selection of projects by associations is influenced by the fact that they must then make their resources available for those projects. On the one hand, this constrains the activities of associations, but on the other it enables them to undertake projects in concert with the local government in terms of both design and implementation.

6. Discussion

The case study evidences the transition described by Hofbauer Balmori (2003) and Sharp (2002) from a gender auditing to a gender budgeting approach, with the increasing incorporation of gender topics into the planning and allocation of resources by the municipality. This process, partly stimulated by the rationing of state transfers, entails a public-private revision of the relationship; but it also gives the gender budget greater incisiveness in the local government’s management. The shift from the assessment of the gender impacts (direct and indirect) of public policies to their ex-ante definition in gender terms implies a greater involvement of stakeholders. The executive committee and council have given strategic value to the gender budget as a means of enabling better management of increasingly scarce resources.

Moving from gender auditing to gender budgeting entails a change of strategy by the municipality, which provides the basis for incorporating ethics (value and moral principles) into every aspect of its decision-making process (Noland and Phillips 2010). The actors who manage this adoption process are internal and external stakeholders that, in pursuing gender equality, cooperate to achieve a common public aim.

Consequently, stakeholder involvement shifts from being internal to external in that it includes a larger number of actors, and especially those with a different relationship with the municipality. It seems that the adoption of GRB has followed two strategies: in the first phase, the “expert-bureaucratic” model prevailed; in the second, the “participative-democratic” strategy drives the development of the gender budget. In this regard, the GRB developed in the municipality of Bologna demonstrates the existence of a third way that combines aspects of both these models. In most cases, Italian GRBs provide for the use of a mixed method that enhances the participation of gender experts located generally within and outside institutions (Equal Opportunities Department; Elected Women’s Commission) and the contribution of the community as represented by civic groups and voluntary associations with an interest in gender issues, i.e., the GRB stakeholders.

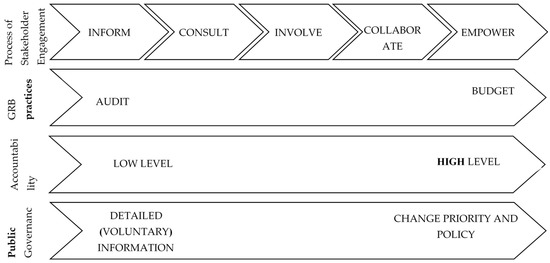

With reference to Figure 1, gender auditing foresees a stakeholder engagement based on communication, or indeed consultation, as evidenced by the first experience of Bologna. In fact, the latter has issued information on the principle followed, but it has also addressed the needs of citizens through a two-way communication. GRB requires greater involvement and cooperation in the design and implementation of projects, as highlighted by the development of the initiative in Bologna. The process described above, by which associations are selected and involved in the choice of significant gender policies, and the manner in which they are implemented, moves in this direction. It has now reached the “collaborate” stage involving the co-production of services in which public resources and those of associations are coordinated to implement projects whose strategic value is jointly shared.

Figure 1.

Summary of the above considerations on stakeholder engagement.

Moving toward collaboration, and then to potential empowerment, requires the administration to give marked strategic and operational clarity both to its interior and in its relations with stakeholders. The complex gender-based reclassification of the activities and projects undertaken by the municipality of Bologna configures a pervasive accountability procedure that lays the bases for greater transparency of processes, and their joint assessment with internal and external stakeholders. The concept of professional accountability, as defined by Gray and Jenkins (1993), can therefore be found, according to which communication toward the outside to create some sort of social pact between local governments and the external environment acquires consensus and resources.

As Foo wrote (Foo et al. 2011, p. 712), “Co-production by local administrations and stakeholders is congruent with the recent government policies to facilitate users’ choice and personalisation in public service provision. In addition, involving stakeholders in co-production may increase their confidence and so lead to increased participation”. The elements cited in the quotation quite clearly express one of the distinctive features of public governance, which—by involving external stakeholders through a participative process—defines new forms of strategic dialogue and collaboration in the management of resources. This requires the administration to move from voluntary reports to a change in priorities, and to policies co-governed by the public administration and stakeholders on participative bases. Consequently, accountability must be strengthened and must give account to activities from their design to their implementation.

As this paper has sought to show, GRB in Bologna has impacted governance and planning not only by the municipality, but also by the associations themselves, doing so in a potentially virtuous circle, which may generate projects of real importance for the community. Hence, the thoughts of Noland and Phillips (2010) receive valid support because the engagement of stakeholders must be integral to local governments’ strategies without a distinction between morality and strategy.

7. Conclusions

Presently, public governance agendas indicate equality as one of the most important goals in creating opportunities for all citizens. The present study contributes to the existing literature as it investigates how GRB may be a tool to fulfil the public governance agenda.

Equality is accomplished when the decision-making process is aware of the different needs, characteristics, and priorities of men and women. If governments at national or local levels insist on gender-blind budgets, they will not be able to achieve the goal of an efficient and effective allocation of resources. In terms of accountability, GRB makes institutions more aware of the consequences of their decisions on civil society, thus giving citizens a new tool to evaluate the use of public resources.

Furthermore, the involvement of stakeholders from the outset supports a dialogue on how local governments decide and act in promoting activities addressed on gender issues and closer to citizens’ concerns. This entails an analysis of relevant stakeholders (which would guarantee citizens’ needs and the community’s well-being) and a shared process of cultural change. In other words, it has sought to clarify the communication process in stakeholder engagement because participative processes require increased involvement in order to guarantee accountability for decision-making acts and outcomes. The municipality of Bologna has provided useful evidence of the positive impact of GRB on gender policy.

First, stakeholder engagement creates, in various stages of GRB adoption, both a cycle of accountability and a co-production of (gender) policies and activities. Second, the process with which associations and other stakeholders have been selected and included for the choices of these policies and activities has an impact on their effectiveness. Third, GRB within a stakeholder engagement strategy addresses the challenges of diversity and gender inequalities. In this way, GRB gives effectiveness to the public decision-making processes, contributing to a greater incisiveness of the local government’s management and creating gender-sensitive governance processes.

Because there is little existing knowledge on GRB practices and public governance mechanisms, this study encourages research in Italian and international public settings. Other examples of the use of stakeholder theory in GRB initiatives are also desirable.

From the practical point of view, this paper underlines the need to involve stakeholders in the entire process of GRB adoption, promoting a participative gender mainstreaming strategy as the basis for an in-depth recasting of public policies and activities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, G.G., G.V.B. and C.C.; Methodology, G.V.B.; Project administration, G.G.; Validation, C.C.; Writing—original draft, G.V.B. and C.C.; Writing—review and editing, G.G.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Barreca, Manuela. 2012. Stakeholders’ Involvement in Cultural Districts: A Multiple Case Studies Analysis. Paper presented at Euram Conference, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, June 6–8; Available online: http://euram2012.mindworks.ee/public/papers/paper/629 (accessed on 28 June 2013).

- Beck, Tony. 1999. Using Gender-Sensitive Indicators. A Reference Manual for Governments and Other Stakeholders. London: Commonwealth Secretariat, ISBN 0-85092-594-0. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ner, Avner, and Theresa Van Hoomissen. 1991. Nonprofit organizations in the mixed economy. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics 62: 549–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettio, Francesca, Annalisa Rosselli, and Giovanna Vingelli. 2002. Gender Auditing dei Bilanci Pubblici. Bergamo: Fondazione A. J. Zaninoni. [Google Scholar]

- Bovaird, Tony. 2005. Public governance: Balancing stakeholder power in a network society. International Review of Administrative Sciences 71: 217–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovaird, Tony, and Elke Löffler. 2002. Moving from excellence models of local service delivery to benchmarking of ‘good local governance’. International Review of Administrative Sciences 68: 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, Alyson. 2009. Gender and Governance: Overview Report. London: Bridge Development-Gender, ISBN 978-185864-576X. [Google Scholar]

- Bryson, John M. 2004. What to do when stakeholders matter. Stakeholder identification and analysis techniques. Public Management Review 6: 21–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, John. M., Kathryn S. Quick, Carissa Schively Slotterback, and Barbara C. Crosby. 2012. Designing public participation processes. Public Administration Review 73: 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budlender, Debbie. 2000. The political economy of Women’s Budgets in the South. World Development 28: 1365–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budlender, Debbie. 2002. A Global Assessment of Gender Responsive Budget Initiatives. In Gender Budgets Make Cents: Understanding Gender Responsive Budgets. Edited by Debbie Budlender, Diane Elson, Guy Hewitt and Tanni Mukhopadhyay. London: Commonwealth Secretariat, ISBN 0-85092-696-3. [Google Scholar]

- Budlender, Debbie. 2007. Gender-Responsive Call Circulars and Gender Budget Statements. Guidance Sheet Series, No. 1. New York: United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM). [Google Scholar]

- Budlender, Debbie, and Guy Hewitt. 2002. Gender Budgets Make More Cents: Country Studies and Good Practice. London: Commonwealth Secretariat, ISBN 0-85092-734-X. [Google Scholar]

- Budlender, Debbie, and Guy Hewitt. 2003. Engendering Budgets. A Practitionersʼ Guide to Understanding and Implementing Gender Responsive Budgets. London: Commonwealth Secretariat, ISBN 0-85092-735-8. [Google Scholar]

- Budlender, Debbie, Rhonda Sharp, and Kerry Allen. 1998. How to do a Gender Sensitive Budget Analysis: Contemporary Research and Practice. London: Commonwealth Secretariat, ISBN 0-86803-615-3. [Google Scholar]

- Budlender, Debbie, Diane Elson, Guy Hewitt, and Tanni Mukhopadhyay. 2002. Gender Budgets Make Cents: Understanding Gender Responsive Budgets. London: Commonwealth Secretariat, ISBN 0-85092-696-3. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, Juliet, and Anselm Strauss. 1990. Grounded Theory research: Procedures, canons and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology 13: 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. 2005. Gender Budgeting: Final Report of the Group of Specialists on Gender Budgeting. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the European Union. 2006. Renewed EU Sustainable Development Strategy. Brussels: Council of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Cumming, Jane Fiona. 2001. Engaging stakeholders in corporate accountability programmes: A cross-sectoral analysis of UK and transnational experience. Business Ethics: A European Review 10: 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elander, Ingemar. 2002. Partnerships and urban governance. International Social Science Journal 172: 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elson, Diane. 1998. Policy Arena: Integrating gender issues into national budgetary policies and procedures: some policy options. Journal of International Development 10: 929–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elson, Diane. 1999. Gender Budget Initiative. London: Commonwealth Secretariat. [Google Scholar]

- Elson, Diane. 2002. Gender Responsive Budget Initiatives: Key Dimensions and Practical Examples. In Gender Budget Initiatives: Strategies, Concepts and Experiences. Coordinated by Jennifer Klot, Nathalie Holvoet and Elizabeth Villagomez. Edited by Karen Judd. New York: United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM), ISBN #0-912917-60-1. [Google Scholar]

- Elson, Diane. 2006. Budgeting for Women’s Rights: Monitoring Government Budgets for Compliance with CEDAW. New York: United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM), ISBN 1-932827-47-1. [Google Scholar]

- Foo, Loke-Min, Darinka Asenova, Stephen Bailey, and John Hood. 2011. Stakeholder engagement and compliance culture. An empirical study of Scottish private finance initiative projects. Public Administration Review 13: 707–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. Edward. 1984. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Boston: Pitman, ISBN 978-0-521-15174-0. [Google Scholar]

- Municipality of Bologna. 2008. Gender Auditing Report 2008. Available online: http://www.iperbole.bologna.it/rendicontazione-sociale/genere/docs/BILANCIO_DI_GENERE_DOCUMENTO_2008.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2010).

- Gray, Andrew, and Bill Jenkins. 1993. Codes of accountability in the new public sector. Accounting Auditing and Accountability Journal 6: 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, Guy, and Tanni Mukhopadhyay. 2002. Promoting Gender Equality through Public Expenditure. In Gender Budgets Make Cents: Understanding Gender Responsive Budgets. Edited by Debbie Budlender, Diane Elson, Guy Hewitt and Tanni Mukhopadhyay. London: Commonwealth Secretariat, ISBN 0-85092-696-3. [Google Scholar]

- Himmelweit, Susan. 2002. Making visible the hidden economy: The case for gender-impact analysis of economic policy. Feminist Economics 8: 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofbauer Balmori, Helena. 2003. Gender and Budgets: Overview Report. London: Bridge Development-Gender, ISBN 1-85864-461-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, Nigel, and Sue McHale. 2007. A Practical Guide to the E-Mail Interview. Qualitative Health Research 17: 1415–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irvin, Renée A., and John Stansbury. 2004. Citizen participation in decision making: Is it worth the effort? Public Administration Review 64: 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krafchik, Warren. 2002. Can Civil Society Add Value to Budget Decision-Making? In Gender Budget Initiatives: Strategies, Concepts and Experiences. Coordinated by Jennifer Klot, Nathalie Holvoet and Elizabeth Villagomez. Edited by Karen Judd. New York: United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM), ISBN #0-912917-60-1. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, Steiner. 1996. Interviews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing. Thousand Oaks: Sage, ISBN 13-978-0803958197. [Google Scholar]

- Marcuccio, Manila, and Ileana Steccolini. 2009. Patterns of voluntary extended performance reporting in Italian local authorities. International Journal of Public Sector Management 22: 146–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneguzzo, Marco. 1997. Ripensare la modernizzazione amministrativa e il New Public Management. L’esperienza italiana: Innovazione dal basso e sviluppo della governance locale. Azienda Pubblica 6: 587–627. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, Stephanie J., and Gillian Symon. 2004. Electronic interviews in organizational research. In Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research. Edited by Catherine Cassel and Gillian Symon. London: Sage Publications, ISBN 0 7619 4888 0. [Google Scholar]

- Municipality of Bologna. 1991. Statute of the Municipality of Bologna. Available online: http://www.comune.bologna.it/media/files/statuto_consolidato.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2013).

- Municipality of Bologna. 2005. Mandatory Programme 2004–2009. Available online: http://www.comune.bologna.it (accessed on 24 January 2012).

- Nabatchi, Tina. 2012. Putting the “Public” back in public values research: Designing participation to identify and respond to values. Public Administration Review 72: 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noland, James, and Robert Phillips. 2010. Stakeholder engagement, discourse ethics and strategic management. International Journal of Management Reviews 12: 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, Katy, Carol Bacchi, and Catherine Mackenzie. 2008. Gender analysis and community consultation: The role of women’s policy units. The Australian Journal of Public Administration 67: 149–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, Esben Rahbek. 2006. Making Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Operable: How Companies Translate Shareholder Dialogue into Practice. Business and Society Review 111: 137–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubery, Jill, Colette Fagan, Damian Grimshaw, Hugo Figueiredo, and Mark Smith. 2002. Indicators on Gender Equality in the European Employment Strategy. Manchester: European Work and Employment Research Centre, Manchester School of Management UMIST. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, Marilyn Marks, and John R. Bartle. 2005. Integrating Gender into Government Budgets: A New Perspective. Public Administration Review 65: 259–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, Grant T., Timoty W. Nix, Carlton J. Whitehead, and John D. Blair. 1991. Strategies for assessing and managing organizational stakeholders. Academy of Management Executive 5: 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, Rhonda. 2002. Moving Forward: Multiple Strategies and Guiding Goals. In Gender Budget Initiatives: Strategies, Concepts and Experiences. Edited by Karen Judd. Coordinated by Jennifer Klot, Nathalie Holvoet and Elizabeth Villagomez. New York: United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM), ISBN #0-912917-60-1. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, Rhonda. 2003. Budgeting for Equity. Gender Budget Initiatives within a Framework of Performance Oriented Budgeting. New York: United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM), ISBN 0-646-42521-8. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, Rhonda, and Ray Broomhill. 2002. Budgeting for equality: The Australian experience. Feminist Economics 8: 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, Rhonda, and Sanjugta Vas Dev. 2004. Bridging the Gap between Gender Analysis and Gender-Responsive Budgets: Key Lessons from a Pilot Project in the Republic of the Marshall Islands. Working paper Series, No. 25. Adelaide: University of South Australia, Hawke Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). 1999. Human Development Report 1999. New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-521562-1. [Google Scholar]

- Van Puyvelde, Stijn, Ralf Caers, Clind Bois, and Marc Jegers. 2012. The governance of nonprofit organizations: Integrating agency theory with stakeholder and stewardship theories. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 41: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villagomez, Elizabeth. 2004. Gender Responsive Budgets: Issues, good practices and policy options. Paper presented at the Regional Symposium on Mainstreaming Gender into Economic Policies, Geneve, Switzerland, January 28–30. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Robert K. 2003. Case Study Research. Design and Methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, ISBN 0-7619-2553. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman, Elaine. 2005. An Introduction to Gender Budget Initiatives. Available online: http://www.genderaction.org/images/Intro_to_Gender_Budget_InitativesFINAL.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2018).

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).