Sexual Appeals in Advertising: The Role of Nudity, Model Gender, and Consumer Response

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Sexual Appeals in Advertising

1.2. The Role of Nudity

1.3. Audience Characteristics and Gender Differences

1.4. The Present Study

- H1: Advertisements featuring models in swimwear will not yield more favorable attitudes toward the advertisement, brand, or purchase intentions than ads featuring models in outdoor clothing.

- H2: Advertisements featuring both a male and a female model will generate more favorable brand attitudes and purchase intentions than single-gender advertisements.

- H3: The advantage of the both-genders condition will be observed for both male and female participants, thereby reducing gender-based asymmetries in responses.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Stimuli

2.3. Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Attitude Toward the Advertisement

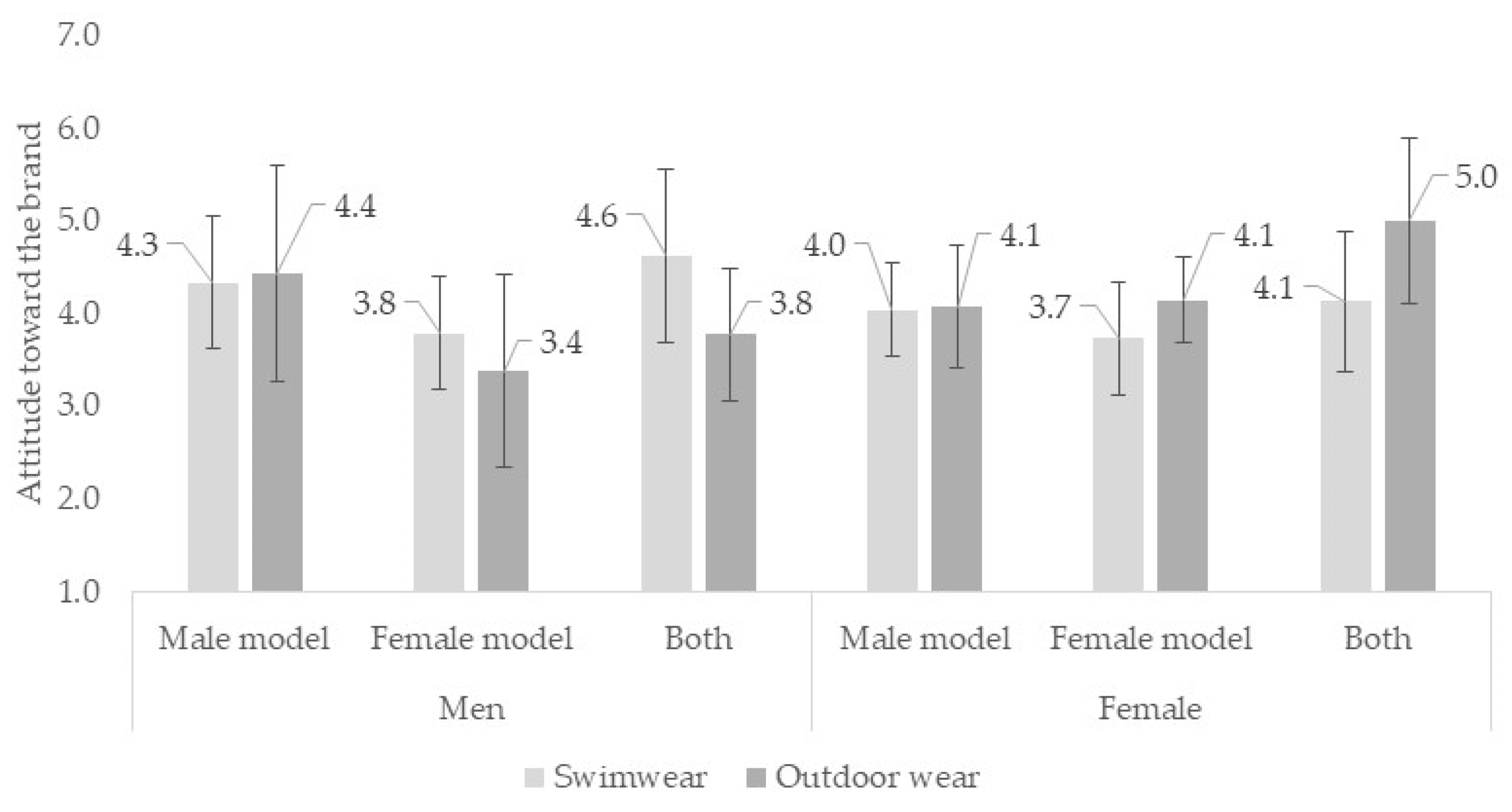

3.2. Attitude Toward the Brand

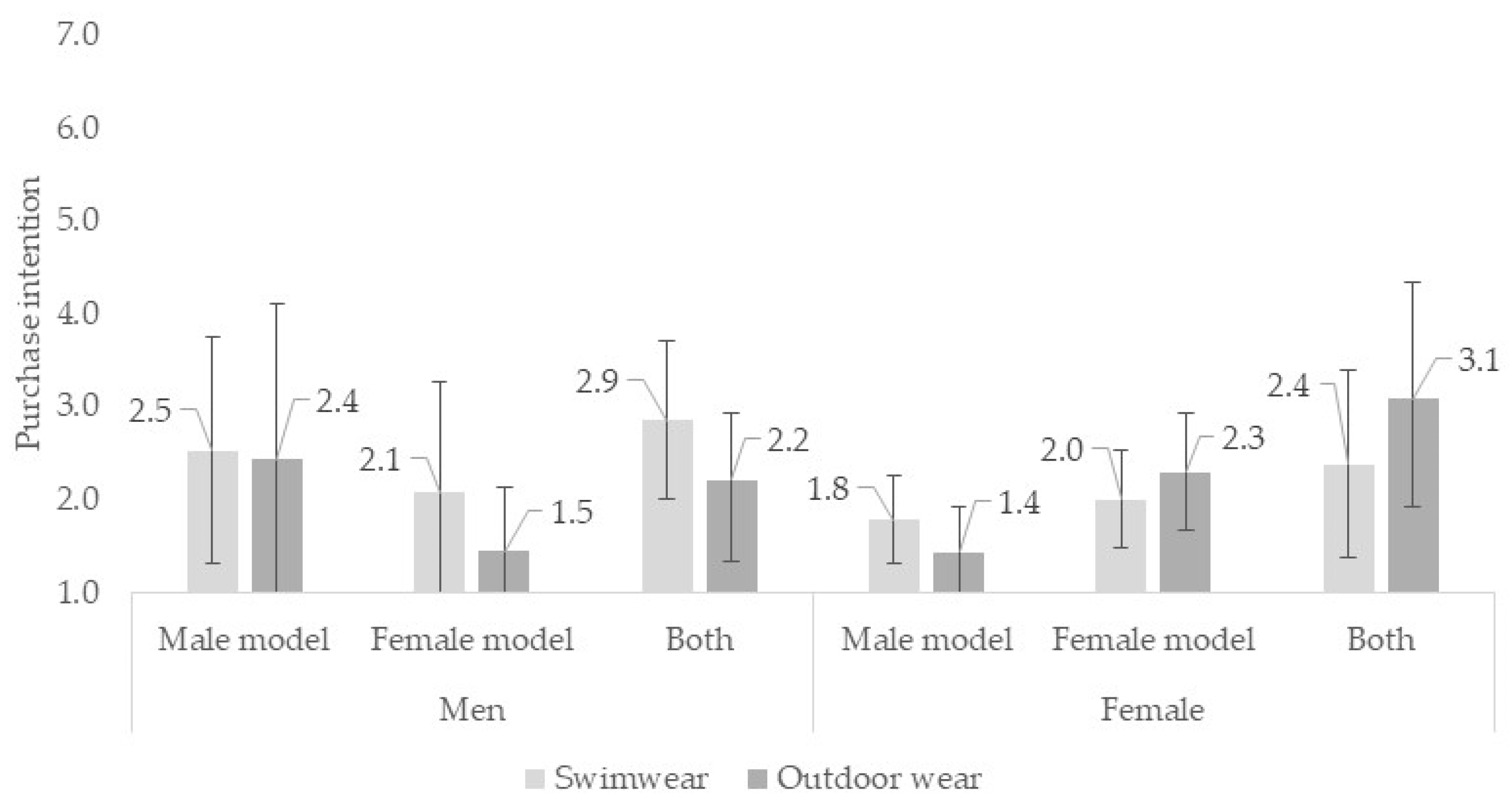

3.3. Purchase Intention

3.4. Mediation Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beales, H., Craswell, R., & Salop, S. C. (1981). The efficient regulation of consumer information. The Journal of Law & Economics, 24, 491–539. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/725275 (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Bello, D. C., Pitts, R. E., & Etzel, M. J. (1983). The communication effects of controversial sexual content in television programs and commercials. Journal of Advertising, 12, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calfee, J. E., & Ringold, D. J. (1988). Consumer skepticism and advertising regulation: What do the polls show? Advances in Consumer Research, 15, 244–248. [Google Scholar]

- Cervone, C., Vezzoli, M., Ruzzante, D., Galdi, S., Formanowicz, M., Guizzo, F., & Suitner, G. (2025). Reveal or conceal your body? Differential manifestations of self-objectification are related to different patterns for women. Body Image, 54, 101920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H., Yoo, K., Hyun Baek, T., Reid, L. N., & Macias, W. (2013). Presence and effects of health and nutrition-related (HNR) claims with benefit-seeking and risk-avoidance appeals in female-orientated magazine food advertisements. International Journal of Advertising, 32, 587–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H., Yoo, K., Reichert, T., & LaTour, M. S. (2016). Do feminists still respond negatively to female nudity in advertising? Investigating the influence of feminist attitudes on reactions to sexual appeals. International Journal of Advertising, 35, 823–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H., Yoo, K., Reichert, T., & Northup, T. (2022). Sexual ad appeals in social media: Effects and influences of cultural difference and sexual self-schema. International Journal of Advertising, 41, 910–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianoux, C., & Linhart, Z. (2010). The effectiveness of female nudity in advertising in three European countries. International Marketing Review, 27, 562–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, S. C. (1999). Consumer attitudes toward nudity in advertising. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 7, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisend, M., & Tarrahi, F. (2016). The effectiveness of advertising: A meta-meta-analysis of advertising inputs and outcomes. Journal of Advertising, 45, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayvishenko, D., Cherniavska, L., Bondarenko, I., Sashchuk, T., Sypchenko, I., & Lebid, N. (2023). The impact of brand social media marketing on the dynamics of the company’s share value. Business: Theory and Practice, 24, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennis, B., & Stroebe, W. (2010). The psychology of advertising. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro, C., Hemsley, A., & Sands, S. (2023). Embracing diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI): Considerations and opportunities for brand managers. Business Horizions, 6, 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J. B., & LaTour, M. S. (1993). Differing reactions to female role portrayals in advertising. Journal of Advertising Research, 33, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T.-A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 173–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halldórsdóttir, S., Hermannsdóttir, A., & Kristinsson, K. (2020). Klædd eða nakin? Áhrif nektar á viðhorf til auglýsinga [Clothed or naked? The effects of nudity on attitudes toward advertising]. Research in Applied Business and Economics, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, I. U., Mazhar, B., Maqsood, F., Nawaz, M. B., & Shahzadi, A. I. (2025). How consumer-centric personalization enhances advertising value: An empirical study on Instagram ad effectiveness. Journal of Internet Commerce, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis (3rd ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Herman, L. E., Udayana, I. B. N., & Farida, N. (2021). Young generation and environmental friendly awareness: Does it the impact of green advertising? Business: Theory and Practice, 22, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K., Kim, C., & Kang, E. Y. (2025). Cross-cultural analysis of influencer marketing: Meta-analysis and meta-regression of factors and effects. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhmann, B. A., & Limbu, Y. B. (2016). Influence of gender stereotypes on advertising offensiveness and attitude toward advertising in general. International Journal of Advertising, 35, 846–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A., Awan, R. A., Qadeer, F., Saeed, Z., & Ali, R. (2023). Attitude toward nudity and advertising in general through the mediation of offensiveness and moderation of cultural values: Evidence from Pakistan and the United States. Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences, 17, 115–134. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/attitude-toward-nudity-advertising-general/docview/2805589088/se-2?accountid=28822 (accessed on 24 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- König, L. S. (2025). Optimising retail environments for older adults: Insights into customer behaviour and organisational performance. Administrative Sciences, 15, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraiwanit, T., Saha, D., & Sharma, R. (2025). Enhancing brand loyalty via viral marketing: Insights from the E-L-M model. International Journal of System Assurance Engineering and Management, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakens, D. (2017). Equivalence tests: A practical primer for t tests, correlations, and meta-analyses. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaTour, M. S. (1990). Female nudity in print advertising: An analysis of gender difference in arousal and ad response. Psychology & Marketing, 7, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaTour, M. S., Pitts, R. E., & Snook-Luther, D. C. (1990). Female nudity, arousal, and ad response: An experimental investigation. Journal of Advertising, 19, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Hu, Y., Qian, H., & Gao, X. (2025). Perceptual regulation of ideal body shape in young women with body shame: An ERP study of cognitive reappraisal. Behavioural Brain Research, 493, 115690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S. B., & Lutz, R. J. (1989). An empirical examination of the structural antecedents of attitude toward the ad in an advertising pretesting context. Journal of Marketing, 53, 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A. B. (2013). Syrian consumers: Beliefs, attitudes, and behavioral responses to internet advertising. Business: Theory and Practice, 14, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthes, J., & Prieler, M. (2020). Nudity of male and female characters in television advertising across 13 countries. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 97, 1101–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A. (2000). Advertising attitudes and advertising effectiveness. Journal of Advertising Research, 40, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A. A., & Olson, J. C. (1981). Are product attribute beliefs the only mediator of advertising effects on brand attitude? Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanés-Sanchez, J., Sánchez-Fernández, M. D., Soares, J. R. R., & Ramón-Cardona, J. (2025). High performance work systems in the tourism industry: A systematic review. Administrative Sciences, 15, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A., Fong-Emmerson, M., D’Alessandro, S., & Ryan, M. (2025). DEI and discrimination in the marketing industry: Exploring the lived experiences in the workplace. Evidence from Western Australia. Australasian Marketing Journal, 14413582251358509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muehling, D. D., & McCann, M. (1993). Attitude toward the ad: A review. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 15, 25–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadlifatin, R., Persada, S. F., Munthe, J. H., Ardiansyahmiraja, B., Redi, A. A. N. P., Prasetyo, Y. T., & Belgiawan, P. F. (2022). Understanding factors influencing traveller’s adoption of travel influencer advertising: An information adoption model approach. Business: Theory and Practice, 23, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D. T., & D’Souza, C. (2025). Recycling shopping behaviour in Australian circular economy: An examination through central and peripheral routes. Resources, Concervation & Recycling Advances, 27, 20028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardun, C. J., & Forde, K. R. (2006). Sexual content of television commercials watched by early adolescents. In T. Reichart, & J. Lambiase (Eds.), Sex in consumer culture: The erotic content of media and marketing (pp. 125–139). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, R. A., & Kerin, R. A. (1977). The female role in advertisements: Some experimental evidence. The Journal of Marketing, 41, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). Communication and persuasion: Central and peripheral routes to attitude change. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollay, R. W., & Mittal, B. (1993). Here’s the beef: Factors, determinants, and segments in consumer criticism of advertising. Journal of Marketing, 57, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, S. (2016). Impact of corporate social responsibility intensity on corporate reputation and financial performance in Indian firms. Business: Theory and Practice, 17, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendergast, B., Liu, P., & Poon, D. T. Y. (2009). A Hong Kong study of advertising credibility. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 26, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z., Li, S., Li, Z., Wei, Y., Wang, N., Zhang, J., Liu, M., & Zhu, H. (2025). The temporal spillover effect of green attribute changes on eco-hotel location scores: The moderating role of consumer environmental involvement. Sustainability, 17, 6593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, T. (2002). Sex in advertising research: A review of content, effects, and functions of sexual information in consumer advertising. Annual Review of Sex Research, 13, 241–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, T., & Carpenter, C. (2004). An update on sex in magazine advertising: 1983 to 2003. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 81(4), 823–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, T., Childers, C. C., & Reid, L. N. (2012). How sex in advertising varies by product category: An analysis of three decades of visual sexual imagery in magazine advertising. Journal of Current Issues of Research in Advertising, 33, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, T., Heckler, S. E., & Jackson, S. (2001). The effects of sexual social marketing appeals on cognitive processing and persuasion. Journal of Advertising, 30, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, T., Latour, M. S., & Kim, J. Y. (2007). Assessing the influence of gender and sexual self-schema on affective responses to sexual content in advertising. Journal of Current Issues and Research in Advertising, 29, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Nebot, R., de Lemus, S., Baltar, A., & Muro, P. M. (2025). Boys and girls can play: Efficacy of a counter-stereotypical intervention based on narratives in young children. Social Psychology of Education, 28, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, P. M., Horton, S., & Brown, G. (1996). Male nudity in advertisements: A modified replication and extension of gender and product effects. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 24, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. N., & Cole, C. A. (1993). The effects of length, content, and repetition on television commercial effectiveness. Journal of Marketing Research, 30, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spears, N., & Singh, S. N. (2004). Measuring attitude toward the brand and purchase intentions. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 26, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strategy Online. (2023, November 15). 2023 Brand of the year: The beauty of dove. Strategy Online. Available online: https://strategyonline.ca/2023/11/15/2023-brand-of-the-year-the-beauty-of-dove/ (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Terlutter, R., Diehl, S., Koinig, I., Chan, K., & Tsang, L. (2021). “I’m (not) offended by whom I see!” The role of culture and model ethnicity in shaping consumers’ responses toward offensive nudity advertising in Asia and western Europe. Journal of Advertising, 51, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trkulja, Z. M., Primorac, D., & Bilic, I. (2024). Exploring the role of socially responsible marketing in promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion in organizational settings. Administrative Sciences, 14, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakratsas, D., & Ambler, T. (1999). How advertising works: What do we really know? Journal of Marketing, 63, 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, J. G., Sparks, J. V., & Zimbres, T. M. (2018). The effect of exposure to sexual appeals in advertisements on memory, attitude, and purchase intention: A meta-analytic review. International Journal of Advertising, 37, 168–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B., Wisse, B., & Lord, R. G. (2025a). Workplace objectification: A review, synthesis, and research agenda. Human Resource Management Review, 35, 101104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B., Zhu, J., Ma, R., & Huang, Y. (2025b). Impact of dual routes of information cues on consumers’ willingness to pay a premium in cross-border e-commerce: The role of product involvement and nutrition safety awareness. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 87, 104428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Correlation Coefficients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | M | Sf | N | 2 | 3 | |

| 1 | Attitude toward the advertisement | 3.17 | 1.42 | 195 | ||

| 2 | Brand attitude | 4.04 | 1.33 | 192 | 0.52 *** | |

| 3 | Purchase intentions | 2.15 | 1.55 | 194 | 0.63 *** | 0.60 *** |

| Pathway | Effect (b) | BootSE | 95% CI | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Both vs. Female → Attitudes toward the ad → Purchase intention | 0.06 | 0.13 | [−0.19, 0.34] | ns |

| Both vs. Female → Brand attitude → Purchase intention | 0.05 | 0.10 | [−0.14, 0.26] | ns |

| Both vs. Female → Attitudes toward the ad → Brand attitude → Purchase intention | 0.03 | 0.06 | [−0.10, 0.15] | ns |

| Male vs. Female → Attitudes toward the ad → Purchase intention | −0.03 | 0.11 | [−0.27, 0.17] | ns |

| Male vs. Female → Brand attitude → Purchase intention | −0.15 | 0.08 | [−0.33, 0.01] | ns |

| Male vs. Female → Attitudes toward the ad → Brand attitude → Purchase intention | −0.02 | 0.05 | [−0.13, 0.09] | ns |

| Comparison | Mediator | Direct Effect (b) | Direct p | Indirect Effect (b) | 95% CI | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male vs. Female | Attitudes toward the ad | 0.10 | ns | −0.05 | [−0.38, 0.25] | ns |

| Both vs. Female | Attitudes toward the ad | 0.55 | 0.016 * | 0.08 | [−0.30, 0.46] | ns |

| Male vs. Female | Brand attitude | 0.32 | ns | −0.27 | [−0.59, 0.05] | ns |

| Both vs. Female | Brand attitude | 0.51 | 0.033 * | 0.13 | [−0.23, 0.50] | ns |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sigurðardóttir, A.K.; Vésteinsdóttir, V.; Gylfason, H.F. Sexual Appeals in Advertising: The Role of Nudity, Model Gender, and Consumer Response. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 363. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090363

Sigurðardóttir AK, Vésteinsdóttir V, Gylfason HF. Sexual Appeals in Advertising: The Role of Nudity, Model Gender, and Consumer Response. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(9):363. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090363

Chicago/Turabian StyleSigurðardóttir, Aníta Karen, Vaka Vésteinsdóttir, and Haukur Freyr Gylfason. 2025. "Sexual Appeals in Advertising: The Role of Nudity, Model Gender, and Consumer Response" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 9: 363. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090363

APA StyleSigurðardóttir, A. K., Vésteinsdóttir, V., & Gylfason, H. F. (2025). Sexual Appeals in Advertising: The Role of Nudity, Model Gender, and Consumer Response. Administrative Sciences, 15(9), 363. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090363