From Expectation and Participation to Satisfaction: The Moderating Role of Perceived Government Responsiveness in Digital Government

Abstract

1. Introduction

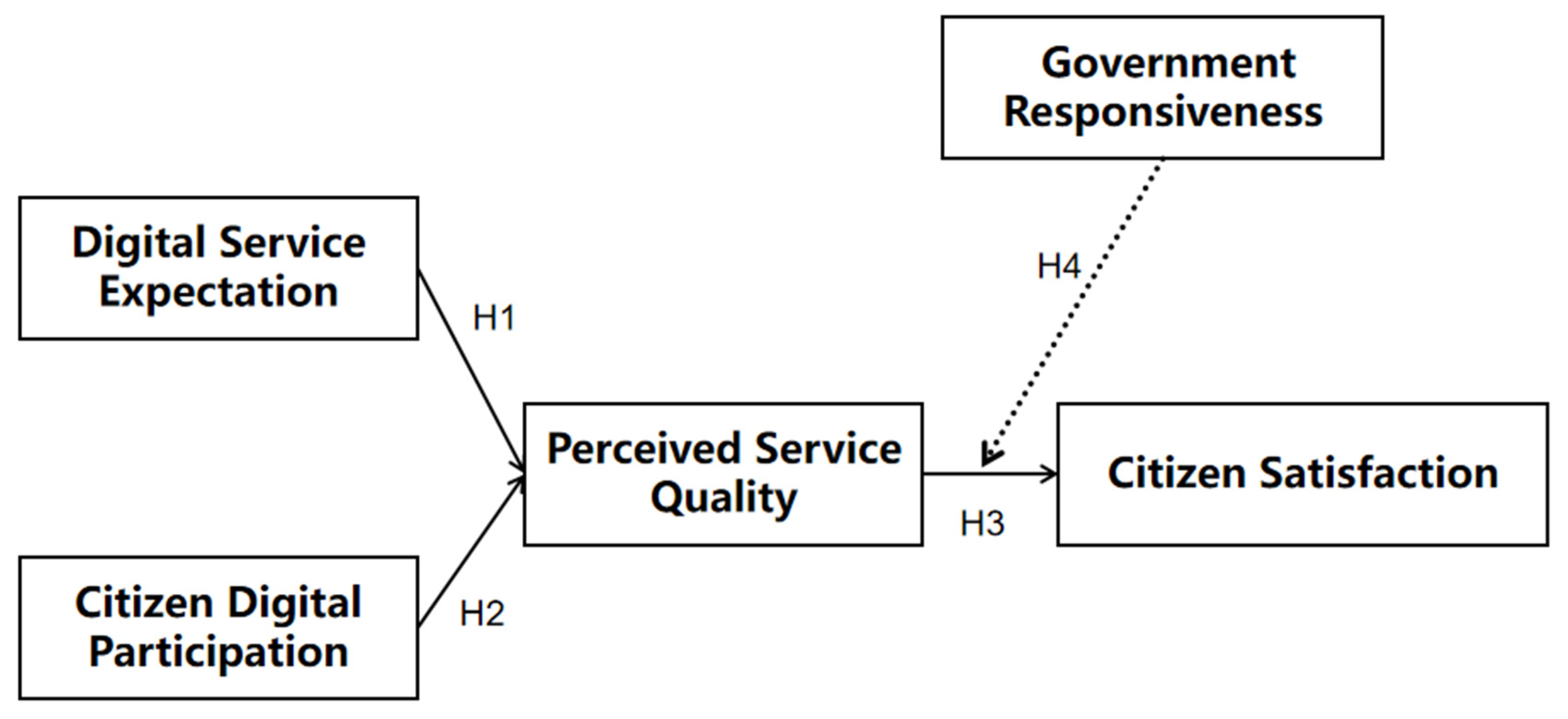

2. Literature Review

2.1. Digital Service Expectations

2.2. Citizen Digital Participation

2.3. The Impact of Perceived Service Quality on Satisfaction

2.4. Government Responsiveness as a Moderating Variable

3. Research Design and Methodology

3.1. Background and Research Context

3.2. Measures

3.3. Sample and Procedure

3.4. Data Analysis Technique

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics

4.2. Measurement Analysis

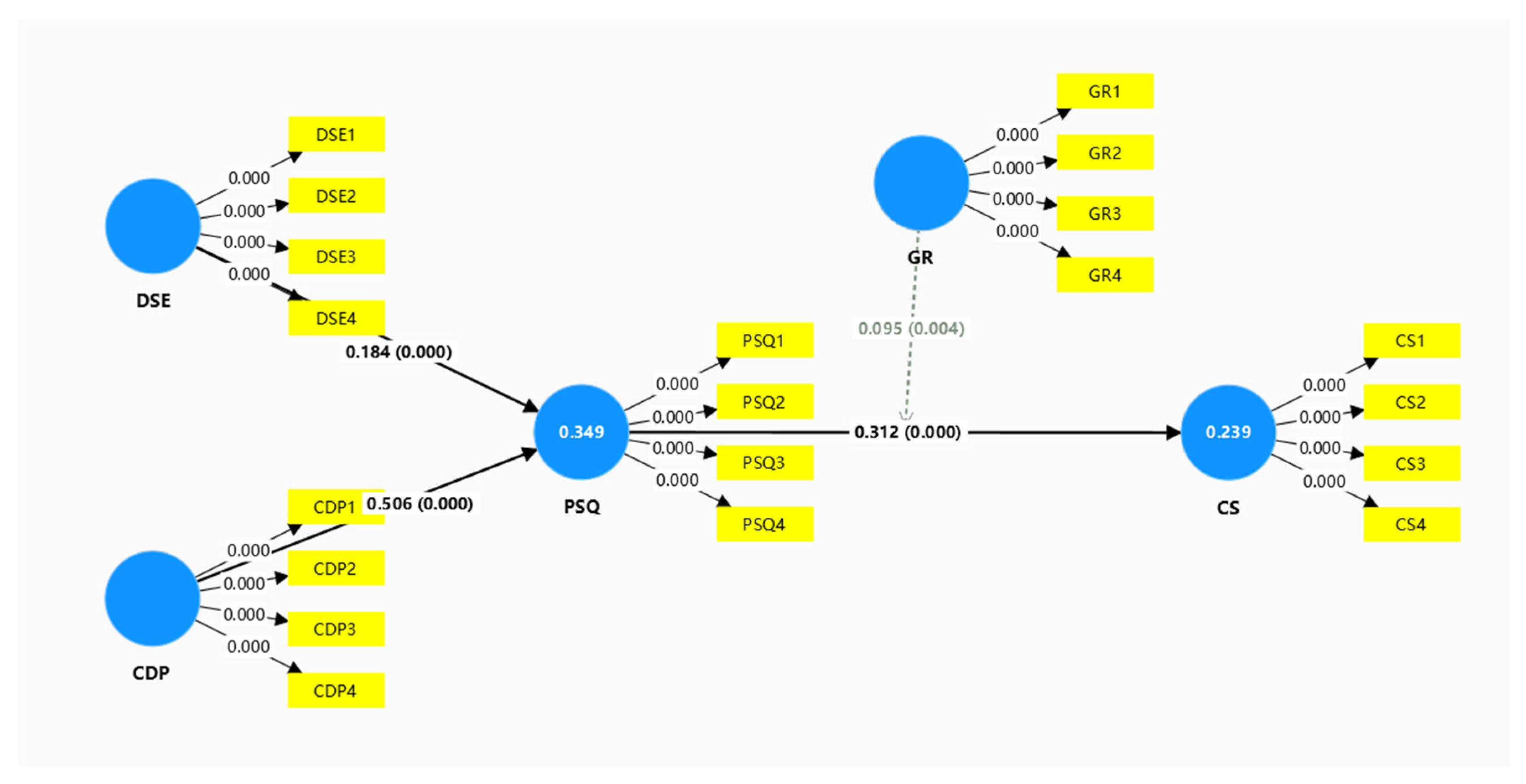

4.3. Evaluation of the Structural Model

4.4. Predictive Relevance (Q2)

5. Discussion

5.1. The Effect of Digital Service Expectations on Perceived Service Quality (H1)

5.2. The Effect of Citizen Digital Participation on Perceived Service Quality (H2)

5.3. Perceived Service Quality and Citizen Satisfaction (H3)

5.4. The Moderating Role of Government Responsiveness (H4)

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ashaye, O. R., & Irani, Z. (2019). The role of stakeholders in the effective use of e-government resources in public services. International Journal of Information Management, 49, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asimakopoulos, G., Antonopoulou, H., Giotopoulos, K., & Halkiopoulos, C. (2025). Impact of information and communication technologies on democratic processes and citizen participation. Societies, 15(2), 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badri, M., Al Khaili, M., & Al Mansoori, R. L. (2015). Quality of service, expectation, satisfaction and trust in public institutions: The Abu Dhabi citizen satisfaction survey. Asian Journal of Political Science, 23(3), 420–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (2012). Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(1), 8–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beh, L.-S., Lee, M. J., Lai, S.-L., & Abd Rahman, N. H. (2022). Are we able to meet the needs of the digitalised future? An analysis of ICT usage and skills among Malaysians in the digital transformation era. Journal of Education and Social Sciences, 21(1), 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Breaugh, J., Gonzalez-Bailon, S., & Linos, E. (2023). Deconstructing complexity: A comparative study of digital transformation in government. Public Administration Review, 83(4), 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C. (2023). Practical models and operational mechanisms of government-enterprise collaboration in the construction of local digital government: A grounded theory study based on Guangdong province’s ‘Yue Sheng Shi’ platform. E-Government, 11, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, F. K. Y., Thong, J. Y. L., Brown, S. A., & Venkatesh, V. (2021). Service design and citizen satisfaction with e-government services: A multidimensional perspective. Public Administration Review, 81(5), 874–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, R., & Suy, R. (2019). An overview of citizen satisfaction with public service: Based on the model of expectancy disconfirmation. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 7(4), 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T., Liang, Z., Yi, H., & Chen, S. (2023). Responsive e-government in China: A way of gaining public support. Government Information Quarterly, 40(3), 101809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D. (2021). Public satisfaction with service quality in government service centers: Evidence from the “One-visit-at-most” reform in H City. Journal of Shandong University (Philosophy and Social Sciences), 2021(1), 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, T., Chen, S., & Hariguna, T. (2021). The empirical study of usability and credibility on intention usage of government-to-citizen services. Journal of Applied Data Sciences, 2(2), 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y., & Zheng, D. (2023). Does the digital economy promote coordinated urban–rural development? Evidence from China. Sustainability, 15(6), 5460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach for structural equation modeling. In Modern methods for business research (pp. 295–336). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Civelek, M. (2018). Essentials of structural equation modeling. Zea E-Books Collection. Available online: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook/64 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Clifton, J., Díaz Fuentes, D., & Llamosas García, G. (2020). ICT-enabled co-production of public services: Barriers and enablers. A systematic review. Information Polity, 25(1), 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordella, A., & Paletti, A. (2017, June 7–9). Value creation, ICT, and co-production in public sector: Bureaucracy, opensourcing and crowdsourcing. 18th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research (pp. 185–194), Staten Island, NY, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, S.-J., & Lee, J. (2022). Digital government transformation in turbulent times: Responses, challenges, and future direction. Government Information Quarterly, 39(2), 101690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2015). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fledderus, J., Brandsen, T., & Honingh, M. E. (2015). User co-production of public service delivery: An uncertainty approach. Public Policy and Administration, 30(2), 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., Johnson, M. D., Anderson, E. W., Cha, J., & Bryant, B. E. (1996). The American customer satisfaction index: Nature, purpose, and findings. Journal of Marketing, 60(4), 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisser, S. (1974). A predictive approach to the random effect model. Biometrika, 61(1), 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Government Forum. (2025). In pursuit of seamless service: How AI is revolutionising citizen-government interactions. Available online: https://www.globalgovernmentforum.com/in-pursuit-of-seamless-service-how-ai-is-revolutionising-citizen-government-interactions/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Guangdong Provincial Government Affairs Service and Data Management Bureau. (2024). Guangdong e-government service platform user statistics. Available online: https://zfsg.gd.gov.cn/gkmlpt/content/4/4659/post_4659931.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com#2594 (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Guo, Y., Dong, P., & Lu, B. (2025). The influence of public expectations on simulated emotional perceptions of AI-driven government chatbots: A moderated study. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 20(1), 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In R. R. Sinkovics, & P. N. Ghauri (Eds.), New challenges to international marketing (Vol. 20). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q., Zhang, L., Zhang, W., & Zhang, S. (2020). Empirical study on the evaluation model of public satisfaction with local government budget transparency: A case from China. SAGE Open, 10(2), 2158244020924064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A. H. H. (2024). Decentralization and its impact on improving public services. International Journal of Social Sciences, 7(2), 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M., & Fan, B. (2024). Citizens’ conscious engagement in digital platforms: Advancing public service delivery within the public service logic framework. Public Management Review, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration, 11(4), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanin, D., & Hermanto, N. (2018). The effect of service quality toward public satisfaction and public trust on local government in Indonesia. International Journal of Social Economics, 46(3), 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latupeirissa, J. J. P., Dewi, N. L. Y., Prayana, I. K. R., Srikandi, M. B., Ramadiansyah, S. A., & Pramana, I. B. G. A. Y. (2024). Transforming public service delivery: A comprehensive review of digitization initiatives. Sustainability, 16(7), 2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G., & Kwak, Y. H. (2012). An open government maturity model for social media-based public engagement. Government Information Quarterly, 29(4), 492–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee-Geiller, S., & Lee, T. (David). (2019). Using government websites to enhance democratic e-governance: A conceptual model for evaluation. Government Information Quarterly, 36(2), 208–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T., & Wang, S. (2021). How to improve the public trust of the intelligent aging community: An empirical study based on the ACSI model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W. (2021). The role of trust and risk in citizens’ e-government services adoption: A perspective of the extended UTAUT model. Sustainability, 13(14), 7671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., & Xu, T. (2017). Public satisfaction model and empirical research on e-government information service quality. E-Government, 2017(9), 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W. (2022). Research on the development status of ‘Yue Sheng Shi’ information service platform under the background of digital government. Jiangsu Science & Technology Information, 39(19), 69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L., & Wu, X. (2020). Citizen engagement and co-production of e-government services in China. Journal of Chinese Governance, 5(1), 68–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z., & Zhu, Y. (2025). Does e-government integration contribute to the quality and equality of local public services? Empirical evidence from China. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 12(1), 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, A., & Bolívar, M. P. R. (2016). Governing the smart city: A review of the literature on smart urban governance. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 82(2), 392–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, M. K. (2020). Digital transformation of public service and administration [Working Paper]. ZBW—Leibniz Information Centre for Economics. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/222522 (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Mo, H., & Beh, L.-S. (2025). Impact of citizen participation through e-government platforms on satisfaction and trust. International Journal of Electronic Governance, 17(1), 86–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgeson, F. V., Hult, G. T. M., Sharma, U., & Fornell, C. (2023). The American Customer Satisfaction Index (ACSI): A sample dataset and description. Data in Brief, 48, 109123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgeson, F. V., III. (2013). Expectations, disconfirmation, and citizen satisfaction with the US Federal Government: Testing and expanding the model. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 23(2), 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, L., & Wang, H. (2023). Government responsiveness and citizen satisfaction: Evidence from environmental governance. Governance, 36(4), 1125–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nookhao, S., & Kiattisin, S. (2023). Achieving a successful e-government: Determinants of behavioral intention from Thai citizens’ perspective. Heliyon, 9(8), e18944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2024). Global trends in government innovation 2024: Fostering human-centred public services. OECD Publishing. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/global-trends-in-government-innovation-2024_c1bc19c3-en.html (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Omar, A., Weerakkody, V., & Millard, J. (2016, March 1–3). Digital-enabled service transformation in public sector: Institutionalization as a product of interplay between actors and structures during organisational change. 9th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance (ICEGOV ’15-’16) (pp. 305–312), Montevideo, Uruguay. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, S. P., Radnor, Z., & Strokosch, K. (2016). Co-production and the co-creation of value in public services: A suitable case for treatment? Public Management Review, 18(5), 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1988). SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. Journal of Retailing, 64(1), 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Porumbescu, G. (2015). Linking transparency to trust in government and voice. The American Review of Public Administration, 47(5), 520–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z., Liu, B., Cao, Y., Xu, C., & Zhang, J. (2025). Citizens’ expectations about public services: A systematic literature review. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 12(1), 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randma-Liiv, T. (2022). Organizing e-participation: Challenges stemming from the multiplicity of actors. Public Administration, 100(4), 1037–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randma-Liiv, T., Lember, V., Savi, R., & Tonurist, P. (2022). Framework for analysis of the management and impacts of e-participation. In T. Saati, M. J. Mendez, & T. Davies (Eds.), E-participation in Europe: Practice and policy (pp. 21–39). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Rigdon, E. E. (2012). Rethinking partial least squares path modeling: In praise of simple methods. Long Range Planning, 45(5), 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangsawang, T., & Yang, L. (2025). Predicting student achievement using socioeconomic and school-level factors. Artificial Intelligence in Learning, 1(1), 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scupola, A., & Mergel, I. (2022). Co-production in digital transformation of public administration and public value creation: The case of Denmark. Government Information Quarterly, 39(1), 101650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y., Cheng, Y., & Yu, J. (2023). From recovery resilience to transformative resilience: How digital platforms reshape public service provision during and post COVID-19. Public Management Review, 25(4), 710–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, B., Floch, J., Rask, M., Bæck, P., Edgar, C., Berditchevskaia, A., Mesure, P., & Branlat, M. (2024). A systematic analysis of digital tools for citizen participation. Government Information Quarterly, 41(3), 101954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjoberg, F. M., Mellon, J., & Peixoto, T. (2017). The effect of bureaucratic responsiveness on citizen participation. Public Administration Review, 77(3), 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, M., Sicilia, M., & Howlett, M. (2018). Understanding co-production as a new public governance tool. Policy and Society, 37(3), 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z., & Meng, T. (2016). Selective responsiveness: Online public demands and government responsiveness in authoritarian China. Social Science Research, 59, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Špaček, D., & Špačková, Z. (2022). Issues of e-government services quality in the digital-by-default era—The case of the national e-procurement platform in Czechia. Journal of Public Procurement, 23(1), 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsby, J., Stowers, G. N. L., Wolslegel, K., & Tumbuan, E. (2017). Understanding the content and features of open data portals in American cities. Government Information Quarterly, 34(1), 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F., Zhou, J., & Liu, F. (2025). Construction of the national fitness public service satisfaction model in China based on American Customer Satisfaction Index. PLoS ONE, 20(1), e0317551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valackiene, A., & Giedraitiene, J. (2024). A model of public sector E-services development efficiency as a sustainable competitive advantage. Administrative Sciences, 14(9), 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Noordt, C., Medaglia, R., & Tangi, L. (2023). Policy initiatives for artificial intelligence-enabled government: An analysis of national strategies in Europe. Public Policy and Administration, 40(2), 215–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrabie, C. (2025). Improving municipal responsiveness through AI-powered image analysis in E-Government. Public Policy and Administration, 24(1), 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., & Ma, L. (2022). Digital transformation of citizens’ evaluations of public service delivery: Evidence from China. Global Public Policy and Governance, 2(4), 477–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Long, X., Li, L., Kong, L., Zhu, X., & Liang, H. (2020). Engagement factors for waste sorting in China: The mediating effect of satisfaction. Journal of Cleaner Production, 267, 122046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Li, J., Ma, W., Li, Y., Xiong, X., & Yu, X. (2023). Fiscal decentralization and citizens’ satisfaction with public services: Evidence from a micro survey in China [SSRN Scholarly Paper 4625729]. Social Science Research Network. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, B. W., & Kurtz, O. T. (2017). Determinants of citizen usage intentions in e-government: An empirical analysis. Public Organization Review, 17(3), 353–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, G., Esembe, E. E., & Chen, J. (2022). The mixed effects of e-participation on the dynamic of trust in government: Evidence from Cameroon. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 82(1), 69–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadulla, A. R., Nadella, G. S., Maturi, M. H., & Gonaygunta, H. (2024). Evaluating behavioral intention and financial stability in cryptocurrency exchange app: Analyzing system quality, perceived trust, and digital currency. Journal of Digital Market and Digital Currency, 1(2), 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Frequencies (N = 647) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items | Frequency | Percent (%) | Cumulative Percent (%) | |

| Gender | Male | 306 | 47.3 | 47.3 |

| Female | 341 | 52.7 | 100.0 | |

| Age | 18 years old and below | 77 | 11.9 | 11.9 |

| 19–30 years old | 130 | 20.1 | 32.0 | |

| 31–40 years old | 148 | 22.9 | 54.9 | |

| 41–50 years old | 128 | 19.8 | 74.7 | |

| 51–60 years old | 113 | 17.5 | 92.1 | |

| 61 years old and above | 51 | 7.9 | 100.0 | |

| Occupation | Farmer | 62 | 9.6 | 9.6 |

| Laborer | 72 | 11.1 | 20.7 | |

| Individual businessman | 96 | 14.8 | 35.5 | |

| Retired | 45 | 7.0 | 42.5 | |

| Student | 140 | 21.6 | 64.1 | |

| Enterprise employee | 75 | 11.6 | 75.7 | |

| Organization and institution employee | 123 | 19.0 | 94.7 | |

| Other | 34 | 5.3 | 100.0 | |

| Education level | Junior high school (junior college) and below | 46 | 7.1 | 7.1 |

| High school | 87 | 13.4 | 20.6 | |

| Vocational/technical school | 144 | 22.3 | 42.8 | |

| Undergraduate | 209 | 32.3 | 75.1 | |

| Graduate and above | 161 | 24.9 | 100.0 | |

| Household income range (RMB) | Less than 5000 | 48 | 7.4 | 7.4 |

| 5001–10,000 | 56 | 8.7 | 16.1 | |

| 10,001–15,000 | 97 | 15.0 | 31.1 | |

| 15,001–20,000 | 128 | 19.8 | 50.9 | |

| 20,001–25,000 | 159 | 24.6 | 75.4 | |

| 25,001–30,000 | 104 | 16.1 | 91.5 | |

| More than 30,000 | 55 | 8.5 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 647 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| Construct | Min | Max | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Service Expectation (DSE) | 1 | 5 | 2.93 | 1.01 |

| Citizen Participation (CDP) | 1 | 5 | 3.52 | 1.04 |

| Perceived Service Quality (PSQ) | 1 | 5 | 3.54 | 1.04 |

| Citizen Satisfaction (CS) | 1 | 5 | 3.18 | 0.98 |

| Government Responsiveness (GR) | 1 | 5 | 2.85 | 1.06 |

| Structural Path | VIF Value |

|---|---|

| CDP → PSQ | 1.115 |

| DSE → PSQ | 1.115 |

| PSQ → CS | 1.172 |

| GR × PSQ → CS | 1.031 |

| Construct | Item | Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha (α) | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citizen Digital Participation | CDP1 | 0.893 | 0.89 | 0.924 | 0.753 |

| CDP2 | 0.866 | ||||

| CDP3 | 0.851 | ||||

| CDP4 | 0.86 | ||||

| Digital Service Expectation | DSE1 | 0.876 | 0.863 | 0.907 | 0.709 |

| DSE2 | 0.813 | ||||

| DSE3 | 0.842 | ||||

| DSE4 | 0.836 | ||||

| Perceived Service Quality | PSQ1 | 0.897 | 0.895 | 0.927 | 0.761 |

| PSQ2 | 0.872 | ||||

| PSQ3 | 0.853 | ||||

| PSQ4 | 0.868 | ||||

| Government Responsiveness | GR1 | 0.886 | 0.879 | 0.917 | 0.734 |

| GR2 | 0.836 | ||||

| GR3 | 0.851 | ||||

| GR4 | 0.854 | ||||

| Citizen Satisfaction | CS1 | 0.882 | 0.848 | 0.898 | 0.688 |

| CS2 | 0.816 | ||||

| CS3 | 0.81 | ||||

| CS4 | 0.807 |

| Citizen Digital Participation | Citizen Satisfaction | Digital Service Expectation | Government Responsiveness | Perceived Service Quality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citizen Digital Participation | 0.868 | ||||

| Citizen Satisfaction | 0.419 | 0.829 | |||

| Digital Service Expectation | 0.322 | 0.42 | 0.842 | ||

| Government Responsiveness | 0.385 | 0.392 | 0.46 | 0.857 | |

| Perceived Service Quality | 0.565 | 0.395 | 0.346 | 0.347 | 0.872 |

| Hypothesized Path | Path Coefficient (β) | t-Value | p-Value | Supported? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDP → PSQ | 0.506 | 15.612 | <0.001 | Yes |

| DSE → PSQ | 0.184 | 5.283 | <0.001 | Yes |

| PSQ → CS | 0.312 | 8.801 | <0.001 | Yes |

| GR × PSQ → CS | 0.095 | 2.859 | 0.004 | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mo, H.; Beh, L.-S. From Expectation and Participation to Satisfaction: The Moderating Role of Perceived Government Responsiveness in Digital Government. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 364. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090364

Mo H, Beh L-S. From Expectation and Participation to Satisfaction: The Moderating Role of Perceived Government Responsiveness in Digital Government. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(9):364. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090364

Chicago/Turabian StyleMo, Hongjing, and Loo-See Beh. 2025. "From Expectation and Participation to Satisfaction: The Moderating Role of Perceived Government Responsiveness in Digital Government" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 9: 364. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090364

APA StyleMo, H., & Beh, L.-S. (2025). From Expectation and Participation to Satisfaction: The Moderating Role of Perceived Government Responsiveness in Digital Government. Administrative Sciences, 15(9), 364. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090364