1. Introduction

Over the past three decades, emotional intelligence (EI) has become a critical construct in organizational behavior, management, and leadership discourse (

Alvarez-Hevia, 2023;

Chakkaravarthy & Bhaumik, 2025;

Riaz, 2024). First introduced by

Salovey and Mayer (

1990) and further developed by

Goleman (

1995), EI refers to the ability to understand, manage, and utilize emotions effectively in oneself and others. Goleman’s model, which identifies five core components, namely, self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy, and social skills, has become a foundational framework for evaluating emotional competencies in leadership. Numerous studies have linked EI to enhanced communication, conflict resolution, leadership efficacy, and employee satisfaction (

Alwali & Alwali, 2022;

Schlegel et al., 2018;

Woime & Shato, 2025).

EI assumes heightened significance during periods of crisis, such as economic recessions, which are often marked by declining growth, high unemployment, shrinking budgets, and organizational uncertainty. In these conditions, emotionally intelligent leaders are better equipped to sustain employee engagement, manage stress, and foster a shared sense of purpose despite external challenges (

Matunga et al., 2020;

Z. Wang et al., 2024). According to

Deb et al. (

2023), EI enables managers to leverage emotional understanding to support employees in emotionally challenging contexts, thereby reinforcing organizational trust and resilience.

The Lebanese context presents a particularly compelling setting for examining EI’s role in leadership. The country has been grappling with an ongoing economic crisis characterized by currency devaluation, banking failures, public debt, and political instability (

Jabbour Al Maalouf et al., 2024). These challenges have created a highly unpredictable and resource-scarce environment for businesses and employees alike (

Yacoub & Al Maalouf, 2023). Previous studies have demonstrated EI’s contribution to leadership success and organizational effectiveness in general terms (

Wong et al., 2023;

Arshad et al., 2023), but few have explored how each EI component impacts employee performance in deeply unstable economic settings like Lebanon’s.

This study aims to address this gap by investigating how emotionally intelligent managers influence employee performance amid turbulence. It seeks to understand how specific EI competencies, namely self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy, and social skills, affect employee performance under crisis conditions.

The key contribution of this study lies in its contextual and conceptual focus. While EI has been widely examined in stable, Western organizational environments, this research explores its role in a deeply unstable, under-resourced, and culturally nuanced setting, Lebanon. By disaggregating EI into its core dimensions, this study reveals which competencies are most critical during times of uncertainty, offering a more precise understanding of EI’s function in leadership. This context-sensitive and multidimensional approach advances EI theory by situating it within real-world instability, and it enriches leadership discourse in the fields of organizational behavior and human resource management.

The research provides a holistic analysis of EI’s contribution to leadership success and employee engagement in resource-constrained markets, offering valuable insights for leadership development and human resource strategies in similarly volatile environments.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Mainstream Literature

2.1.1. Emotional Intelligence

EI has become central to research in organizational behavior and leadership due to its ability to shape how individuals perceive, process, and manage emotions within complex workplace dynamics. Initially conceptualized by

Salovey and Mayer (

1990) and later popularized by

Goleman (

1995), EI encompasses five core competencies essential for effective leadership: self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy, and social skills. These dimensions influence not only interpersonal functioning but also how leaders manage stress, build relationships, and guide team performance, especially in uncertain or crisis-prone environments.

Self-awareness refers to the capacity to recognize and understand one’s emotions, triggers, and the effects they have on others (

Goleman, 2018). This internal clarity enables leaders to act consistently, make reflective decisions, and align behaviors with organizational values. Empirical studies show that self-aware leaders foster higher trust and employee engagement by demonstrating authenticity (

Boyatzis, 2021;

Michinov & Michinov, 2022). In crisis settings, such as those marked by ambiguity or emotional strain, self-awareness allows managers to maintain focus and make ethical choices under pressure (

Görgens-Ekermans & Roux, 2021).

Self-regulation is the ability to manage one’s emotional responses, control impulses, and remain composed in stressful situations (

Goleman, 2018). Leaders with high self-regulation avoid reactive behaviors, display flexibility, and promote stability in their teams. This competency is particularly beneficial during turbulent times, where emotional contagion can escalate anxiety (

Ashkanasy & Daus, 2020). Research in healthcare and hospitality sectors confirms that self-regulated leaders help mitigate burnout and sustain morale under crisis (

Brackett et al., 2012;

Jena, 2022).

Motivation, as an EI dimension, involves an internal drive to achieve goals and maintain optimism despite obstacles. Motivated leaders are characterized by ambition, persistence, and passion for growth (

Matta & El Alam, 2023). Studies have linked managerial motivation with employee innovation, proactive behavior, and resilience in adversity (

Bayighomog & Arasli, 2022;

Prentice, 2023). In resource-scarce or unstable environments, such as those found in the Global South, this intrinsic motivation becomes crucial for sustaining team momentum when external incentives are lacking (

Waglay et al., 2020).

Empathy is the ability to recognize and understand others’ emotional states and perspectives. It includes both cognitive empathy (understanding others’ viewpoints) and emotional empathy (feeling what others feel) (

Zaki, 2020). Empathetic leadership has been shown to increase employee satisfaction, reduce conflict, and improve psychological safety in high-stress roles (

McKay et al., 2024). Neuroscientific evidence, such as the activation of mirror neurons, supports empathy’s biological role in relationship building (

Rizzolatti & Craighero, 2004). During crises, empathy helps managers detect subtle emotional cues and provide targeted support to employees under strain.

Social skills refer to a leader’s ability to communicate effectively, resolve conflicts, and build cooperative relationships (

Goleman, 1995). These skills include verbal and non-verbal communication, active listening, persuasion, and managing team dynamics (

Liu et al., 2022). Research indicates that socially skilled managers are instrumental in maintaining cohesion and coordination during periods of instability (

Boyatzis, 2021;

Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). In cultures where workplace relationships are central, such as Lebanon, social skills serve as a critical mechanism for navigating interpersonal tension and fostering collective performance.

In summary, each EI dimension contributes uniquely to leadership effectiveness and employee performance, particularly under conditions of uncertainty. While EI has been widely studied in stable settings, fewer studies have empirically examined how these dimensions function within fragile economies or prolonged crisis environments. This gap is central to the current study, which investigates how emotionally intelligent leadership influences performance in Lebanon’s high-stress organizational landscape.

2.1.2. Employee Performance

Employee performance broadly refers to how individuals meet job expectations and contribute to organizational effectiveness. Most models categorize performance into three areas: task performance, contextual performance, and counterproductive behavior (

Rahman et al., 2021;

Dhoopar et al., 2022). Job performance is not only influenced by technical skills and motivation but also by leadership style, emotional climate, and psychological well-being (

Swaidan & Jabbour Al Maalouf, 2025;

Panditharathne & Chen, 2021).

Recent studies support a strong relationship between emotionally intelligent leadership and employee outcomes. For example,

Miao et al. (

2021) and

X. Wang and Shaheryar (

2020) demonstrate that EI enhances resilience, innovation, and job satisfaction, particularly in volatile work environments. In contrast, contexts marked by emotional neglect or authoritarian leadership often see declines in trust, morale, and productivity (

Park et al., 2021). Hence, emotionally intelligent leadership is increasingly viewed as a buffer against workplace instability.

2.2. Theoretical Framework

2.2.1. Emotional Intelligence Theory

EI has been conceptualized through various theoretical lenses, most notably the ability model (

Mayer et al., 2004), the trait model (

Petrides & Furnham, 2001), and the mixed model proposed by

Goleman (

1995,

2018). The ability model views EI as a set of cognitive–emotional abilities, including emotion perception, facilitation, understanding, and regulation. In contrast, the trait model situates EI within the personality domain, focusing on emotional self-perceptions and behavioral tendencies. Goleman’s mixed model integrates emotional competencies, such as self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy, and social skills, combining both ability and trait dimensions to capture the social and affective competencies that are especially relevant in organizational contexts.

Despite its widespread application, the mixed model has been critiqued for conceptual ambiguity and measurement challenges (

Joseph & Newman, 2010;

Zeidner et al., 2008). Nonetheless, its practical appeal lies in its emphasis on observable emotional behaviors and its relevance to workplace leadership and team dynamics, especially under stressful or crisis conditions. Compared to the more abstract cognitive focus of the ability model or the broad personality orientation of the trait model, Goleman’s framework offers a context-sensitive, managerial perspective that aligns closely with this study’s emphasis on leadership effectiveness during economic and institutional crises.

Therefore, Goleman’s model was selected as the theoretical foundation for this research. It allows for the operationalization of EI in leadership roles through its five distinct yet interrelated dimensions that directly influence how managers support, engage, and motivate employees. In environments marked by instability, such as Lebanon, these competencies become crucial mechanisms for enhancing emotional resilience, maintaining performance, and fostering psychological safety. Goleman’s model, thus, provides a robust framework for investigating the links between emotional capacity, leadership behavior, and employee outcomes in fragile organizational ecosystems.

2.2.2. Job Demands–Resources Theory

Complementing EI theory, the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model (

Bakker & Demerouti, 2007) provides a contextual lens. The JD-R framework explains how job demands, such as overload and uncertainty, and resources, such as autonomy and supervisor support, interact to impact performance and well-being. In resource-depleted environments such as crisis-hit countries, EI acts as an internal and external resource, helping leaders regulate team stress and sustain engagement (

Ayub et al., 2021). This theoretical integration supports the hypothesis that emotionally intelligent managers function as stabilizing agents during crises.

2.3. Research Context

Lebanon represents a highly relevant and underexplored context for testing the effects of EI on employee performance under crisis. The country has faced a confluence of systemic crises, economic collapse, political paralysis, and infrastructure breakdown, making it one of the most fragile economies globally (

Al Maalouf et al., 2023;

Bejjani et al., 2024). Employees are grappling with job insecurity, psychological distress, and organizational instability, conditions that place significant emotional demands on leaders and teams. In such fragile environments, emotionally intelligent leadership is not a supplementary asset but a vital stabilizing force for sustaining employee performance and morale.

Despite these challenges, Lebanon also offers a culturally rich setting that shapes how EI is enacted and perceived. As a collectivist and high-context society, Lebanon emphasizes social harmony, group loyalty, and interpersonal sensitivity in both formal and informal workplace interactions (

El-Kassar & Singh, 2019). Emotional expressions tend to be nuanced and indirect, conveyed through tone, gestures, and relational cues rather than overt verbalization. In such cultures, traits like empathy and emotional regulation take on heightened importance, as leaders are expected to navigate conflict delicately, preserve “face,” and promote cohesion through implicit rather than confrontational communication. Social skills and emotional restraint may, thus, be perceived as signs of competence and care, reinforcing a leader’s credibility and emotional authority.

This cultural framework also affects how employees interpret emotionally intelligent behaviors. For instance, a leader’s ability to manage tension non-confrontationally or display empathy through tone and non-verbal cues may foster greater trust and commitment than direct emotional disclosure. The relevance and salience of each EI dimension may, therefore, differ from Western, individualistic models, where expressive assertiveness is often encouraged. Recognizing these cultural dynamics is crucial for understanding how EI operates in Lebanon and why it may be differently expressed or valued in other cultural contexts.

Importantly, while Lebanon shares many characteristics with other fragile states, such as Venezuela and Zimbabwe, including economic collapse, institutional dysfunction, and social fragmentation, it also exhibits distinctive features. The country’s crisis is internally driven, prolonged, and largely absent of international stabilization mechanisms. These conditions make informal leadership, emotional resilience, and interpersonal trust particularly salient in sustaining organizational function. Compared to Western crisis contexts, where structural safety nets and formal supports are more common, Lebanon’s reliance on relational and emotionally intelligent leadership is more pronounced.

Despite cultural and structural specificities, the findings of this study offer theoretical and practical insights that are cautiously transferable to other fragile or crisis-affected environments. Settings marked by high emotional strain, resource scarcity, and institutional voids are likely to exhibit similar demands for emotionally intelligent leadership. While cultural expressions of EI may differ, the underlying mechanisms, such as self-regulation, empathy, and emotional support, retain their significance. Therefore, this study positions Lebanon as a critical case: not necessarily representative of all crisis environments but illustrative of key emotional leadership patterns that merit further investigation in other socio-political and cultural contexts.

2.4. Hypotheses Development

EI plays a central role in shaping leadership effectiveness and employee outcomes. Managers who exhibit high EI tend to communicate better, foster trust, and sustain motivation as key drivers of performance, especially in crisis settings (

Goleman, 2020). Studies show that emotionally intelligent leaders reduce stress, enhance teamwork, and create psychologically safe environments, which directly improve job satisfaction and productivity (

Brunetto et al., 2020;

McKinley et al., 2015).

While prior studies affirm the importance of EI in leadership and organizational performance, there is a clear gap in understanding how its dimensions operate in crisis contexts marked by chronic stress and institutional fragility. Most existing research focuses on developed economies or short-term disruptions such as COVID-19, leaving a gap in investigating EI’s long-term impact in protracted crisis environments. This study addresses that gap by testing the differentiated impact of each EI dimension on employee performance during ongoing economic collapse, situating the inquiry in Lebanon, a crisis context with global relevance but limited scholarly coverage, and integrating emotional intelligence theory with the JD-R framework to explore how EI functions as a strategic leadership resource in resource-constrained environments.

During economic downturns, their ability to guide teams with empathy and clarity becomes essential. Thus, the following main hypothesis is proposed: The EI of managers has a positive impact on employee performance in turbulent times.

Self-awareness enables managers to understand their emotional responses and align their behavior with organizational goals. Self-aware leaders offer more authentic communication, make reflective decisions, and build trusting relationships—all of which enhance team morale and performance (

Boyatzis, 2021;

Görgens-Ekermans & Roux, 2021). This competency is especially valuable in high-pressure environments like Lebanon, where clarity and emotional grounding are essential. Accordingly, the first sub-hypothesis was developed as follows:

H1. Self-awareness in managers has a significant positive impact on employee performance amid turbulent times.

Self-regulation allows managers to manage emotional responses and maintain stability under stress. Leaders who remain composed during uncertainty model emotional discipline for their teams, which can reduce anxiety and support productivity (

Tang et al., 2020;

Ashkanasy & Daus, 2020). In volatile environments, self-regulated leadership becomes a behavioral anchor for team consistency. Therefore, the second sub-hypothesis is as follows:

H2. Self-regulation in managers has a significant positive impact on employee performance during uncertainty.

Motivated leaders energize their teams by demonstrating persistence, optimism, and a strong sense of purpose. In crisis conditions, this internal drive helps counteract low morale and limited external incentives (

Kaur & Sharma, 2019;

Waglay et al., 2020). Motivation not only enhances personal performance but also inspires similar attitudes among employees. Thus, the third sub-hypothesis was developed as follows:

H3. Motivation in managers has a significant positive impact on employee performance amid turbulent times.

Empathy enables leaders to understand and respond to employee concerns, fostering trust and inclusiveness. Empathetic managers are better equipped to manage conflict, support mental well-being, and promote team cohesion (

Zhao et al., 2019;

Xu et al., 2019). In emotionally charged environments, such sensitivity enhances employee commitment and performance. Thus, the fourth sub-hypothesis was developed as follows:

H4. Empathy in managers has a significant positive impact on employee performance during periods of instability.

Socially skilled managers foster productive relationships, manage interpersonal dynamics, and promote teamwork. These skills help resolve conflicts diplomatically and maintain open communication, critical for performance under stress (

Waglay et al., 2020;

Kaur & Sharma, 2019). In Lebanon’s relational work culture, such skills are vital for organizational continuity. Thus, the fifth sub-hypothesis was developed as follows:

H5. Social skills in managers have a significant positive impact on employee performance amid turbulent times.

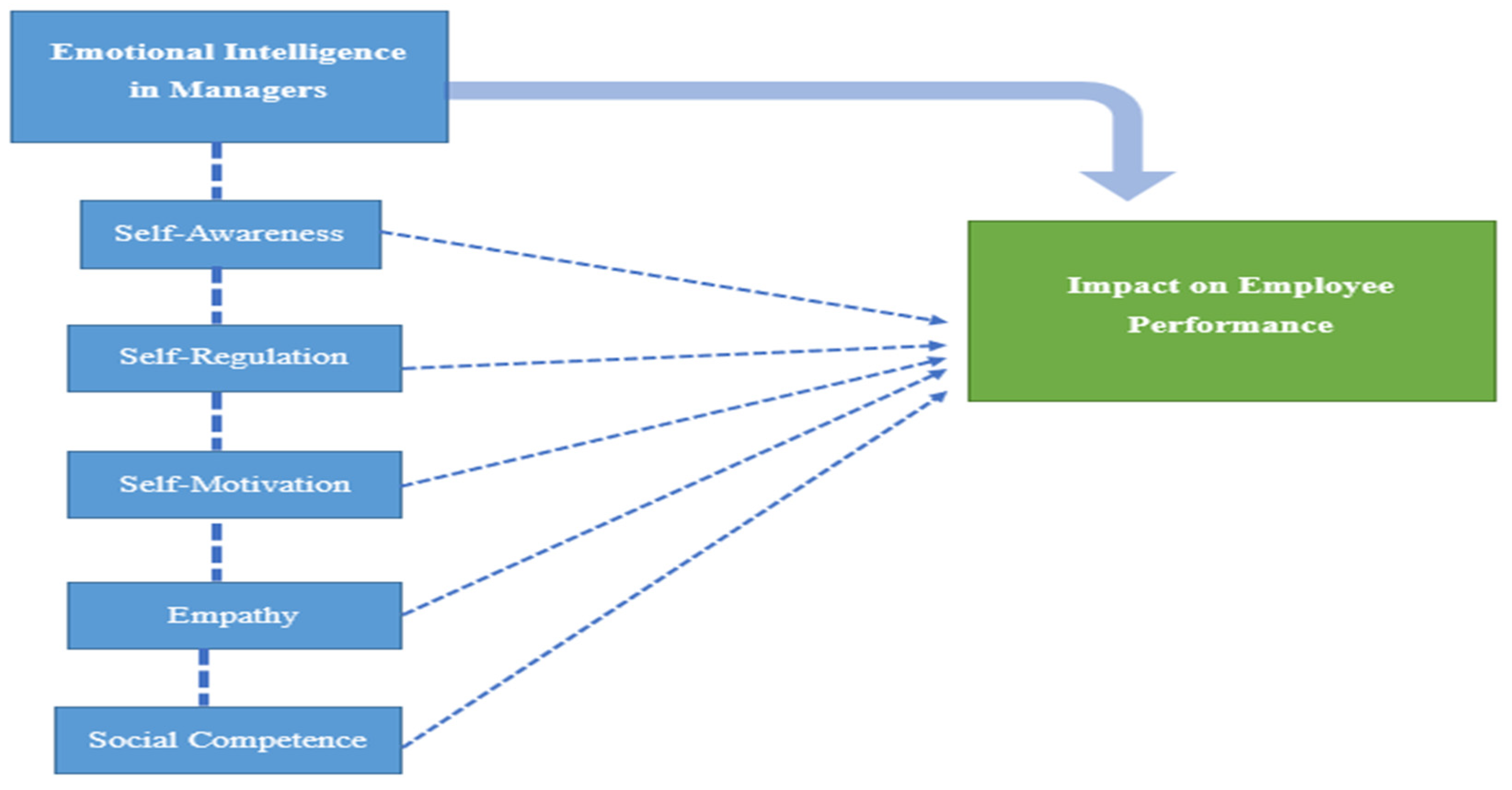

Figure 1 illustrates the hypothesized model, linking EI dimensions to employee performance within the Lebanese crisis context. These hypotheses aim to clarify not only whether EI matters but which dimensions matter most and under what conditions, thereby offering actionable insights for leadership development in volatile environments. Unlike prior models, which typically assess EI as a global or aggregate construct in stable or Western contexts, this study contributes a differentiated, dimension-level analysis of EI in a protracted crisis setting. By integrating emotional intelligence theory with the JD-R framework and situating the model within Lebanon’s fragile, relationally driven economy, this study advances our theoretical understanding of emotional leadership as a critical resource under systemic adversity.

3. Methodology

This study adopts a positivism philosophy and employs a deductive reasoning approach. Aligned with this paradigm, a quantitative mono-method was implemented to investigate the relationship between managers’ EI and employee performance in Lebanon during times of crisis.

3.1. Instrumentation

A structured survey was used for data collection due to its efficiency in capturing standardized responses, broad participation, and statistical comparison. The questionnaire consisted of three sections: demographic data, EI assessment based on Goleman’s five-component model, and employee performance metrics.

The questionnaire was adapted from established and validated scales to match the context of Lebanon. Self-awareness was measured using 5 statements from the Emotional Self-Awareness Questionnaire (ESQ) by

Killian (

2012), with items such as “I can describe my emotions accurately.” Self-regulation was assessed using 5 items related to emotional control and impulse management (e.g., “I stay calm under pressure”). Motivation was measured using 5 items reflecting intrinsic drive and persistence, including “I set challenging goals for myself.” Regarding empathy, 5 statements were adapted from the Empathy Assessment Scale (

Malakcioglu, 2022), with statements like “I can put myself in someone else’s shoes.” Social skills were evaluated through 5 items on communication and conflict solutions (e.g., “I build rapport easily with people”). Finally, employee performance was measured using the Endicott Work Productivity Scale (EWPS) (

Endicott & Nee, 1997), including items such as “I complete my work efficiently.” All items were scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree), ensuring consistency and granularity.

The survey was pilot tested with 20 Lebanese employees to ensure reliability, clarity, and cultural relevance. Minor wording adjustments were made based on feedback. To ensure accessibility, both English and Arabic versions were made available. Translation followed a back-translation protocol to maintain semantic consistency.

To further ensure the cultural appropriateness of the EI scales, the questionnaire was reviewed by bilingual experts familiar with Lebanese workplace norms. Their review focused on the cultural relevance and clarity of emotional constructs in the local context. While a full psychometric revalidation was beyond the scope of this study, the pilot results indicated high internal consistency across all EI dimensions (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.85). These steps support the instrument’s contextual suitability for use in Lebanon’s high-context, collectivist environment.

3.2. Population and Sample Selection

A simple random sampling technique was employed, targeting full-time employees in Lebanon, regardless of sector or seniority, to ensure generalizability across the Lebanese working population. Eligibility criteria included being currently employed in Lebanon, aged 18 years or older, and providing informed consent. The survey link was distributed via email and social media platforms, targeting diverse occupational groups. Data were collected in April 2025 using Google Forms. The survey was widely disseminated across multiple platforms to minimize sampling bias. From a workforce of approximately 1.66 million (

International Labour Organization, 2024), a sample of 398 employees was obtained.

Although participants were drawn from a variety of sectors to enhance generalizability, the analysis did not disaggregate results by industry. This is acknowledged as a limitation.

Written informed consent was obtained before filling out the questionnaire with a filter question to ensure participants voluntarily agreed to participate in this study. Ethical approval was secured.

A cross-sectional time horizon was adopted, capturing employee perceptions at a single point in time during Lebanon’s ongoing economic crisis. This snapshot approach allowed for the measurement of EI and performance relationships under acute stress conditions.

3.3. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using JASP software version 0.18.3, and Covariance-Based SEM (CB-SEM) was chosen due to its appropriateness for theory confirmation, reflective measurement models, and global model fit evaluation. Before SEM, several checks were conducted. No missing values were recorded, with no outliers.

To assess normality, both skewness and kurtosis were examined for each item. All values fell within the accepted range of ±2, indicating no substantial violations of univariate normality. Multicollinearity was assessed using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) analysis, with all VIF values falling below the conservative threshold of 5. These results confirm that the dataset is suitable for SEM.

To assess the robustness of the measurement model, several tests were conducted. Model fit indices confirm the adequacy of the hypothesized structural model. The overall Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) score was 0.907, supporting factor analysis suitability. Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values for all constructs were above 0.50, confirming sufficient variance explained. Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) values were all below 0.90, satisfying the criterion for construct distinctiveness. Cronbach’s Alpha (α) and Coefficient Omega (ω) were computed for all factors. All values exceeded the 0.70 threshold, indicating strong internal consistency.

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of the Findings

The results of this study confirm the significant and positive influence of all five EI dimensions on employee performance during turbulent times, reinforcing the central hypothesis and aligning with the theoretical propositions of Goleman’s EI framework (

Goleman, 1995) and the JD-R theory (

Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). This supports existing scholarship that highlights the strategic value of emotionally intelligent leadership, especially in crisis contexts.

However, the findings go further by disaggregating the relative impact of each EI component, offering nuanced insights into their contextual relevance for fragile environments such as Lebanon. This context-sensitive contribution helps bridge the gap in existing research, which has largely focused on developed or short-term disrupted environments.

Self-regulation emerged as the most influential factor (β = 0.485) followed by empathy (β = 0.361). This hierarchy warrants deeper contextual reflection. One plausible explanation is that during protracted crises, leaders are not only expected to manage operational challenges but also to stabilize emotionally volatile environments. In such contexts, self-regulation becomes essential for suppressing panic, managing interpersonal tension, and modeling composure under pressure, critical leadership behaviors when formal structures are weak or failing. This aligns with research by

Ashkanasy and Daus (

2020) and

Tang et al. (

2020), who identify emotional regulation as a central mechanism for psychological containment during organizational distress.

Lebanon’s high-context and collectivist culture places substantial value on relational closeness, emotional attunement, and non-verbal communication. In this environment, empathy is not merely an individual trait but a relational currency that fosters loyalty, group cohesion, and moral legitimacy (

El-Kassar & Singh, 2019). Leaders who exhibit empathy signal understanding and care, which can substitute for absent institutional support and promote retention. This cultural dynamic partially explains why empathy had a greater impact than motivational or social skills, which may be less visible or emotionally resonant in daily interactions.

Also, the salience of self-regulation and empathy may reflect the psychological needs of employees facing chronic uncertainty, where emotional containment and interpersonal reassurance are more urgent than strategic communication (social skills) or goal orientation (motivation). Additionally, these results may stem from the sample’s emotional framing of effective leadership during crisis; traits like calmness and emotional support may be more recognizable and appreciated under distress than introspective or expressive traits such as self-awareness or charisma.

Motivation and social skills had moderate effects (β = 0.137 and β = 0.143, respectively), suggesting that while leaders who inspire or communicate well do contribute to performance, their impact may be constrained by the structural barriers prevalent in Lebanon, such as limited organizational mobility, poor resource availability, and lack of incentives. Notably, self-awareness, though statistically significant, had the weakest effect (β = 0.109), consistent with the idea that introspective capabilities are foundational yet not as visibly impactful in urgent, high-pressure situations (

Boyatzis, 2021). This finding may reflect cultural dynamics where indirect emotional expression is prevalent and transparency is more valued in action than reflection (

Görgens-Ekermans & Roux, 2021). In crises, behaviors with outward social utility, like empathy or impulse control, may be perceived as more valuable than reflective insight, particularly in a culture where indirect emotional expression is normative.

Taken together, the results confirm all five hypothesized relationships between EI dimensions and employee performance. The results suggest a crisis-specific and culturally conditioned hierarchy. Emotionally intelligent leadership is multidimensional, but not all traits are equally valued or impactful in every context. These findings offer context-sensitive insights into which emotional competencies are most critical under prolonged crisis and within relationally driven workplace cultures like Lebanon.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

These findings contribute to theory in several ways. First, they empirically validate the full five-factor structure of Goleman’s EI model within a protracted crisis setting, Lebanon, where emotionally intelligent leadership has seldom been tested. Second, this study extends the JD-R theory by demonstrating how EI traits serve as psychological resources that mitigate the detrimental effects of extreme job demands. Unlike previous research situated in stable environments, this study confirms the cross-cultural and crisis-resilient validity of both frameworks, providing a compelling case for their integration in emerging-market contexts.

First, the results extend Goleman’s EI theory by demonstrating that all five emotional competencies have statistically significant positive effects on employee performance, even in volatile socio-economic contexts such as Lebanon. Notably, self-regulation and empathy emerged as the most impactful dimensions, which supports Goleman’s claim that emotional mastery and interpersonal sensitivity are central to effective leadership. These findings reinforce the theoretical proposition that emotionally intelligent leaders foster psychological safety, emotional balance, and trust, which are essential for sustaining high performance in uncertain conditions (

Goleman, 2018;

Prentice et al., 2020).

Second, this study advances the JD-R theory by empirically positioning EI as a psychosocial job resource that mitigates the negative effects of high job demands. Lebanon’s context, marked by economic collapse, political unrest, and widespread uncertainty, represents an extreme case of elevated job demands. In such settings, emotionally intelligent managers buffer stress by providing emotional regulation, clear direction, and motivational support, which aligns with JD-R’s assertion that resources foster resilience and performance (

Ayub et al., 2021). The high β-values of self-regulation (β = 0.485) and empathy (β = 0.361) confirm that these EI traits function as protective factors, sustaining employee functioning when conventional organizational support may be limited.

Moreover, the integration of both theories illustrates a dynamic interplay between emotional capacity (EI Theory) and situational demand–resource balance (JD-R theory). While Goleman’s framework explains how emotional traits affect behavior, JD-R theory contextualizes why these traits become particularly critical under duress. This study, therefore, contributes to theoretical development by linking micro-level psychological competencies with macro-level workplace stress models, offering a more holistic understanding of leadership efficacy during crises.

Lastly, by applying these theories to a Middle Eastern and crisis-affected context, this study broadens the scope of EI and JD-R frameworks, which have been predominantly validated in stable Western economies. The findings affirm that these theories hold cross-cultural and crisis-relevant validity, encouraging future scholars to explore their intersectionality across diverse organizational ecosystems.

5.3. Practical Implications

The findings of this study provide meaningful insights for organizational leaders, human resource (HR) practitioners, and policymakers, particularly in fragile economies such as Lebanon, on how to leverage EI as a strategic human resource. Importantly, the findings emphasize that not all EI traits contribute equally to employee performance. Emotional self-control (self-regulation) and relational depth (empathy) emerged as the most influential dimensions. This suggests a functional hierarchy within EI traits under pressure, with internal regulation and interpersonal empathy acting as primary performance drivers. In contrast, self-awareness and social skills, while still significant, appear to serve more as enablers than direct catalysts of performance outcomes.

This distinction encourages a move beyond generic EI training toward targeted, context-specific development programs. Leadership development initiatives should prioritize cultivating self-regulation and empathy to mitigate emotional contagion and foster psychological safety, key mechanisms for organizational resilience during crisis.

For practitioners operating in Lebanon and similar environments, emotionally intelligent leadership is not a luxury but a necessity. This study offers cost-effective, scalable recommendations to embed EI into organizational culture without requiring substantial financial investment. First, low-cost, high-impact interventions such as peer mentoring, on-the-job coaching, and structured self-assessment tools are needed to build emotional awareness and behavioral control. Second, it is vital to integrate EI indicators into HR systems, including recruitment, performance appraisal, and promotion processes. For example, competencies such as empathetic listening and emotional composure can be evaluated during interviews or employee evaluations. Finally, it is necessary to have EI-based leadership training, specifically in emotionally demanding sectors like education, healthcare, and public service, where emotionally intelligent leadership directly impacts service quality and workforce retention.

From a broader human capital perspective, EI should be formally recognized as a strategic resource. During periods of high uncertainty when financial rewards are constrained, EI can serve as a non-financial motivator and retention tool. HR departments should incorporate emotionally intelligent behaviors into team management policies, succession planning, and conflict resolution frameworks.

At the policy level, public institutions and NGOs can scale the impact of EI by embedding it into national training curricula and certification programs for leadership. Particularly in Lebanon’s volatile context, such systemic interventions can support improved employee well-being, reduce burnout, and increase organizational performance at the macro level.

In brief, emotionally intelligent leadership offers a sustainable and adaptive response to organizational instability. By developing emotionally intelligent managers, especially those skilled in empathy and self-regulation, organizations can enhance performance, preserve morale, and cultivate workplace cultures resilient to external shocks.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

While this study provides valuable insights into the relationship between EI and employee performance in crisis contexts, several limitations must be acknowledged, offering avenues for future research.

A key limitation lies in the cross-sectional design, which captures data at a single point in time and limits the ability to infer causality. As such, while associations between EI dimensions and employee performance are evident, the temporal sequencing and potential feedback loops between these variables cannot be determined. Future studies should adopt longitudinal research designs to trace the evolution of EI’s impact over different crisis phases and to establish more robust causal inferences.

Another limitation concerns the use of self-reported, employee-only data. While this captured valuable insights into perceived managerial EI, it introduced risks of bias, including social desirability, recall error, and subjective interpretation. The absence of managerial self-assessments or multi-source validation restricts the objectivity of the results. Future studies should adopt multi-source validation, combining employee and manager data to compare perception gaps and improve measurement accuracy.

This study also treats EI components independently but does not explore their interrelations or potential synergies. For instance, motivation and social skills may reinforce one another, just as strong self-regulation can enhance empathy. Future research should examine inter-component dynamics and test whether certain EI traits compensate for weaknesses in others.

Additionally, although this study used validated Likert scales, these may not fully capture culturally specific expressions of emotion in Lebanon’s hybrid Arab–Western work culture. Mixed-methods research combining quantitative surveys with qualitative interviews or ethnographic techniques could offer deeper insights into culturally grounded interpretations of emotional intelligence.

Moreover, although the sample included employees from diverse sectors, the data were not disaggregated by industry. This limits the ability to identify sector-specific dynamics, particularly since stressors and organizational cultures may vary substantially across industries. Future research should explore such distinctions to enhance contextual relevance and practical applicability.

Also, while Lebanon serves as a valuable context due to its prolonged crises, generalizing these findings to other fragile states must be done cautiously. Cross-cultural comparisons across multiple crisis-affected countries would help determine whether the findings are specific to Lebanon or represent broader patterns applicable to similar contexts.

Further, the assumption of “turbulent times” was generalized; however, individual experiences of instability may vary greatly. Longitudinal studies could track how EI effectiveness evolves across different phases of crises, especially in heterogeneous societies like Lebanon, where emotional norms and leadership expectations differ by age group. Moreover, cross-cultural comparisons across crisis-affected regions can help generalize or refine the theoretical model.

Finally, this study invites interdisciplinary exploration. Linking EI to outcomes such as innovation, employee well-being, or retention could expand its application in HR development, particularly in turbulent environments. Combining insights from psychology, leadership, crisis management, and organizational behavior would enrich our understanding of how EI supports sustainable performance in uncertain times.

6. Conclusions

This study examined the influence of five dimensions of EI on employee performance in Lebanon, a country facing ongoing economic collapse and institutional fragility. Using CB-SEM, the analysis confirmed that all five EI dimensions significantly enhance performance, with self-regulation and empathy emerging as the most impactful. These findings underscore EI’s strategic role in leadership, particularly in high-stress, resource-constrained environments.

Theoretically, this study contributes to both Goleman’s EI model and the JD-R framework by demonstrating that emotionally intelligent leadership serves as a stabilizing mechanism during prolonged crises. The validation of EI’s dimensional impact, especially self-regulation and empathy, adds depth to existing models and highlights the psychosocial underpinnings of effective leadership in volatile settings.

Practically, the results advocate for embedding EI into leadership development, recruitment, and appraisal systems. Low-cost, context-appropriate interventions such as peer mentoring, emotional self-assessments, and empathy-based training can help organizations build resilience and maintain performance even under extreme constraints.

By situating EI within a fragile socio-economic context, this study advances a culturally grounded and crisis-responsive understanding of leadership. It positions EI not merely as a desirable competency but as a critical organizational resource. Future research should explore cross-sectoral and cross-cultural comparisons, adopt multi-source or longitudinal methodologies, and examine how different EI dimensions interact to shape organizational outcomes over time.