Effects of a Flipped Classroom College Business Course on Students’ Pre-Class Preparation, In-Class Participation, Learning, and Skills Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Antecedents and Consequences of Business Students’ Pre-Class Preparation

2.2. Antecedents and Consequences of Business Students’ In-Class Participation

3. A Framework of the Flipped Classroom and Associated Hypotheses

3.1. Perceived Usefulness, Pre-Class Preparation, and In-Class Participation

3.2. Pre-Class Preparation, In-Class Participation, Perceived Learning, and Skills Development

4. Method

4.1. Participants

4.2. Course Design

4.3. Instruments

4.3.1. Perceived Usefulness of OFC/IFC

4.3.2. Pre-Class Preparation

4.3.3. In-Class Attendance

4.3.4. Perceived Learning

4.3.5. Perceived Skills Development

4.3.6. Control Variables

4.4. Data Analysis Approach

5. Results

5.1. Construct Validity Test

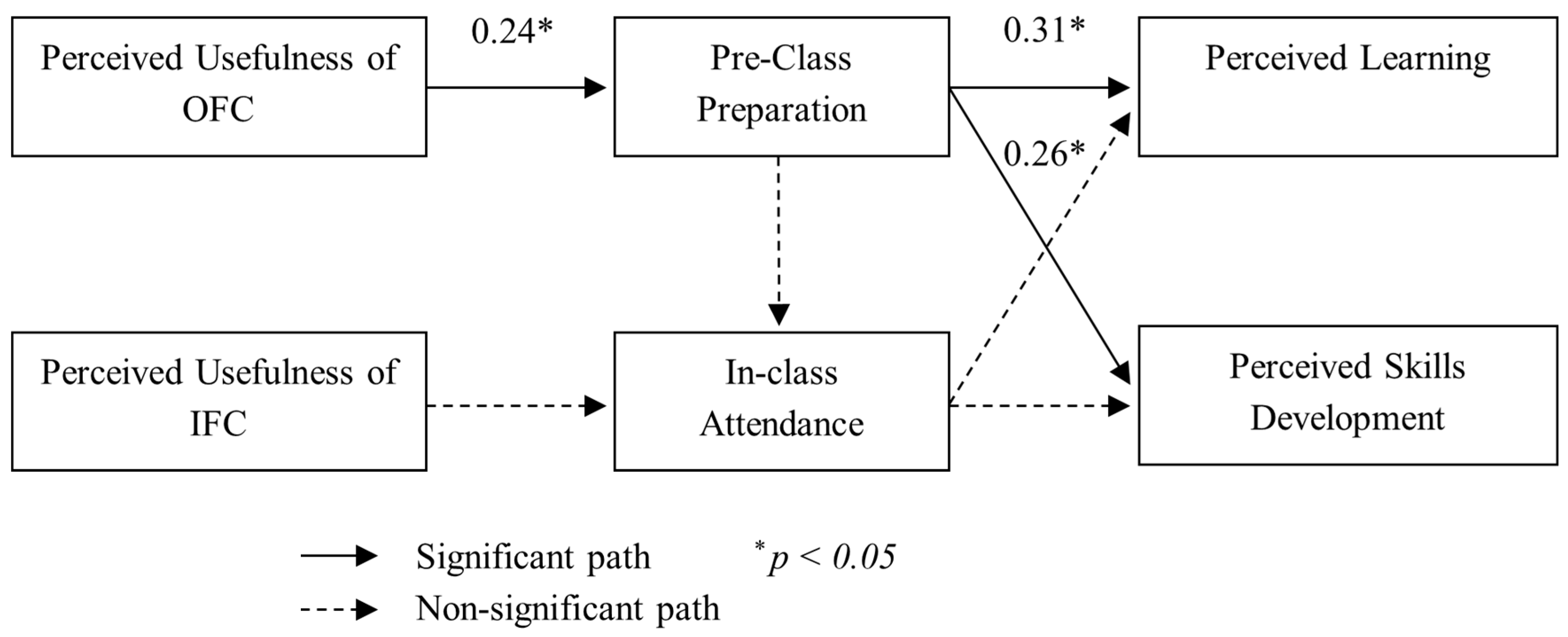

5.2. Perceived Usefulness, Pre-Class Preparation, and In-Class Participation

5.3. Pre-Class Preparation, In-Class Participation, Perceived Learning, and Skills Development

6. Discussion

6.1. Perceived Usefulness, Pre-Class Preparation, and In-Class Participation

6.2. Pre-Class Preparation, In-Class Participation, Perceived Learning, and Skills Development

7. Practical Implications

8. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

9. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abeysekera, L., & Dawson, P. (2015). Motivation and cognitive load in the flipped classroom: Definition, rationale and a call for research. Higher Education Research & Development, 34(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adkins, J. K. (2014). Relevance of student resources in a flipped MIS classroom. Information Systems Education Journal, 12(2), 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Akçayır, G., & Akçayır, M. (2018). The flipped classroom: A review of its advantages and challenges. Computers & Education, 126, 334–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcalde, P., & Nagel, J. (2019). Why does peer instruction improve student satisfaction more than student performance? A randomized experiment. International Review of Economics Education, 30, 100149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Samarraie, H., Shamsuddin, A., & Alzahrani, A. I. (2020). A flipped classroom model in higher education: A review of the evidence across disciplines. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(3), 1017–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asarta, C. J., & Schmidt, J. R. (2015). The choice of reduced seat time in a blended course. The Internet and Higher Education, 27, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asef, V. A. (2015). The flipped classroom of operations management: A not-for-cost-reduction platform. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 13(1), 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaban, R. A., Gilleskie, D. B., & Tran, U. (2016). A quantitative evaluation of the flipped classroom in a large lecture principle of economics course. The Journal of Economic Education, 47(4), 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, R., & Proud, S. (2018). Flipping quantitative tutorials. International Review of Economics Education, 29, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beenan, G., & Arbaugh, B. (2019). Flipping class: Why student expectations and person-situation fit matter. International Journal of Management in Education, 17(3), 100311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beric-Stojsic, B., Patel, N., Blake, J., & Johnson, D. (2020). Flipped classroom teaching and learning pedagogy in the program planning, implementation, and evaluation graduate course: Students’ experiences. Pedagogy in Health Promotion, 6(3), 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J., Kember, D., & Leung, D. Y. P. (2001). The revised two-factor study process questionnaire: R-SPQ-2F. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 71(1), 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeve, A. J., Meijer, R. R., Bosker, R. J., Vugteveen, J., Hoekstra, R., & Albers, C. J. (2017). Implementing the flipped classroom: An exploration of study behaviour and student performance. Higher Education, 74(6), 1015–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borokhovski, E., Bernard, R. M., Tamim, R. M., Schmid, R. F., & Sokolovskaya, A. (2016). Technology-supported student interaction in post-secondary education: A meta-analysis of designed versus contextual treatments. Computers & Education, 96, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burford, M. R., & Chan, K. (2017). Refining a strategic marketing course: Is a “flip” a good “fit”? Journal of Strategic Marketing, 25(2), 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calimeris, L. (2018). Effects of flipping the principles of microeconomics class: Does scheduling matter? International Review of Economics Education, 29, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calimeris, L., & Sauer, K. M. (2015). Flipping out about the flip: All hype or is there hope? International Review of Economics Education, 20, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C., & Yen, P. (2021). Learner control, segmenting, and modality effects in animated demonstrations used as the before-class instructions in the flipped classroom. Interactive Learning Environments, 29(1), 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M. A., Hwang, G., & Chang, Y. (2019). A reflective thinking-promoting approach to enhancing graduate students’ flipped learning engagement, participation behaviors, reflective thinking and project learning outcomes. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(5), 2288–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Wang, Y., Kinshuk, J., & Chen, N. (2014). Is FLIP enough? Or should we use the flipped model instead? Computers & Education, 79, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L., Ritzhaupt, A. D., & Antonenko, P. (2019). Effects of the flipped classroom instructional strategy on students’ learning outcomes: A meta-analysis. Educational Technology Research and Development, 67(4), 793–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J., & Monroe, G. S. (2003). Exploring social desirability bias. Journal of Business Ethics, 44(4), 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comber, D. P. M., & Brady-Van den Bos, M. (2018). Too much, too soon? A critical investigation into factors that make flipped classrooms effective. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(4), 683–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakiroğlu, Ü., Güven, O., & Saylan, E. (2020). Flipping the experimentation process: Influences on science process skills. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(6), 3425–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, J. A., & Foley, J. D. (2006). Evaluating a web lecture intervention in a human-computer interaction course. IEEE Transactions on Education, 49(4), 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLozier, S. J., & Rhodes, M. G. (2017). Flipped classrooms: A review of key ideas and recommendations for practice. Educational Psychology Review, 29(1), 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, S. V., Jabeen, S. S., Abdul, W. K., & Rao, S. A. (2018). Teaching cross-cultural management: A flipped classroom approach using films. International Journal of Management Education (Elsevier Science), 16(3), 405–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diel, R., Avdic, A., & Kemp, P. S. (2020). Flipped ophthalmology classroom: A better way to teach medical students. Journal of Academic Ophthalmology, 12(2), e104–e109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dombrowski, T., Wrobel, C., Dazert, S., & Volkenstein, S. (2018). Flipped classroom frameworks improve efficacy in undergraduate practical courses—A quasi-randomized pilot study in Otorhinolaryngology. BMC Medical Education, 18(294), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downen, T., & Hyde, B. (2016). Flipping the managerial accounting principles course: Effects on student performance, evaluation, and attendance. Advances in Accounting Education, 19(1), 61–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J. S., Adler, T. F., Futterman, R., Goff, S. B., Kaczala, C. M., Meece, J. L., & Midgley, C. (1983). Expectancies, values, and academic behaviors. In J. T. Spence (Ed.), Achievement and achievement motivation (pp. 75–146). W. H. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Elledge, R. (2018). Current thinking in medical education research: An overview. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 56(5), 380–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadol, Y., Aldamen, H., & Saadullah, S. (2018). A comparative analysis of flipped, online and traditional teaching: A case of female middle eastern management students. The International Journal of Management Education, 16(2), 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freguia, S. (2017). Webcasts promote in-class active participation and learning in an engineering elective course. European Journal of Engineering Education, 42(5), 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnjost, P., & Lawter, L. (2019). Undergraduates’ satisfaction and perceptions of learning outcomes across teacher- and learner-focused pedagogies. International Journal of Management Education, 17(2), 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelan, A., Fastre, G., Verjans, M., Martin, N., Janssenswillen, G., Creemers, M., Lieben, J., Depaire, B., & Thomas, M. (2018). Affordances and limitations of learning analytics for computer-assisted language learning: A case study of the VITAL project. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 31(3), 294–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, M., McLean, J., Read, A., Suchet-Pearson, S., & Viner, V. (2017). Flipping and still learning: Experiences of a flipped classroom approach for a third-year undergraduate human geography course. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 41(3), 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, R. D., & Schlairet, M. C. (2017). Moving toward heutagogical learning: Illuminating undergraduate nursing students’ experiences in a flipped classroom. Nurse Education Today, 49, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighi, H., Jafarigohar, M., Khoshsima, H., & Vahdany, F. (2019). Impact of flipped classroom on EFL learners’ appropriate use of refusal: Achievement, participation, perception. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 32(3), 261–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A. A., & DuFrene, D. D. (2016). Best practices for launching a flipped classroom. Business and Professional Communication Quarterly, 79(2), 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, J. (2016). Surveying the experiences and perceptions of undergraduate nursing students of a flipped classroom approach to increase understanding of drug science and its application to clinical practice. Nurse Education in Practice, 16(1), 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y. (2016). Exploring undergraduates’ perspectives and flipped learning readiness in their flipped classrooms. Computers in Human Behavior, 59, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y., & Lee, K. S. (2016). Teaching in flipped classrooms: Exploring pre-service teachers’ concerns. Computers in Human Behavior, 57, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W., Gajski, D., Farkas, G., & Warschauer, M. (2015). Implementing flexible hybrid instruction in an electrical engineering course: The best of three worlds? Computers & Education, 81, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W., Holton, A., Farkas, G., & Warschauer, M. (2016). The effects of flipped instruction on out-of-class study time, exam performance, and student perceptions. Learning and Instruction, 45, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W., Holton, A. J., & Farkas, G. (2018). Impact of partially flipped instruction on immediate and subsequent course performance in a large undergraduate chemistry course. Computers & Education, 125, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C., & Lin, Y. (2017). Flipping business education: Transformative use of team-based learning in human resource management classrooms. Educational Technology & Society, 20(1), 323–336. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2017-03609-025 (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Hung, H. (2015). Flipping the classroom for English language learners to foster active learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 28(1), 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Q. (2019). Effects of digital flipped classroom teaching method integrated cooperative learning model on learning motivation and outcome. The Electronic Library, 37(5), 842–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, J., Gašević, D., Dawson, S., Pardo, A., & Mirriahi, N. (2017). Learning analytics to unveil learning strategies in a flipped classroom. The Internet and Higher Education, 33(4), 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakosimos, K. E. (2015). Example of a micro-adaptive instruction methodology for the improvement of flipped-classrooms and adaptive-learning based on advanced blended-learning tools. Education for Chemical Engineers, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantanen, H., Koponen, J., Sointu, E., & Valtonen, T. (2019). Including the student voice: Experiences and learning outcomes of a flipped communication course. Business & Professional Communication Quarterly, 82(3), 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. K., Kim, S. M., Khera, O., & Getman, J. (2014). The experience of three flipped classrooms in an urban university: An exploration of design principles. The Internet and Higher Education, 22, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S., Pond, K., & Witthaus, G. (2019). Making a difference with lecture capture? Providing evidence for research-informed policy. The International Journal of Management Education, 17(3), 100323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaper, C. (2011). More similarities than differences in contemporary theories of social development? Advances in Child Development and Behavior, 40, 337–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C. K. (2018). Grounding the flipped classroom approach in the foundations of educational technology. Educational Technology Research and Development, 66(3), 793–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A. P., & Soares, F. (2018). Perception and performance in a flipped financial mathematics classroom. International Journal of Management Education, 16(1), 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCord, R., & Jeldes, I. (2019). Engaging non-majors in MATLAB programming through a flipped classroom approach. Computer Science Education, 29(4), 313–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, L. S., Gamst, G., & Guarino, A. J. (2006). Applied multivariate research: Design and interpretation. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Moran, K., & Milsom, A. (2015). The flipped classroom in counselor education. Counselor Education and Supervision, 54(1), 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, I., Cianfrini, M., Clements, J., & Wilson-Rogers, N. (2019). Taxation, innovation and education: Reflections on a flipped lecture room. Journal of the Australasian Tax Teachers Association, 14(1), 122–150. [Google Scholar]

- Pejuan, A., & Antonijuan, J. (2019). Independent learning as class preparation to foster student-centred learning in first-year engineering students. Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 24(4), 375–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pence, P. L. (2016). “Flipping” a first-year medical–surgical associate degree registered nursing course: A 2-year pilot study. Teaching and Learning in Nursing, 11(2), 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picault, J. (2019). The economics instructor’s toolbox. International Review of Economics Education, 30, 100154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P., MacKenzie, S., Jeong-Yeon, L., & Podsakoff, N. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashar, A. (2015). Assessing the flipped classroom in operations management: A pilot study. Journal of Education for Business, 90(3), 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, C., & Walker, M. (2021). Improving the accessibility of foundation statistics for undergraduate business and management students using a flipped classroom. Studies in Higher Education, 46(2), 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, E., Claudius, I., Tabatabai, R., Kearl, L., Behar, S., & Jhun, P. (2016). The flipped classroom in emergency medicine using online videos with interpolated questions. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 51(3), 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R., & Deci, E. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzenberg, P., & Navón, J. (2020). Supporting goal setting in flipped classes. Interactive Learning Environments, 28(6), 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scovotti, C. (2016). Experiences with flipping the marketing capstone course. Marketing Education Review, 26(1), 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherrow, T., Lang, B., & Corbett, R. (2016). The flipped class: Experience in a university business communication course. Business and Professional Communication Quarterly, 79(2), 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinouvassane, D., & Nalini, A. (2016). Perception of flipped classroom model among year one and year three health science students. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 6(3), 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sletten, S. R. (2017). Investigating flipped learning: Student self-regulated learning, perceptions, and achievement in an introductory biology course. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 26(3), 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, B., & Iraj, H. (2016). Implementing flipped classroom using digital media: A comparison of two demographically different groups perceptions. Computers in Human Behavior, 60, 514–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stehle, S., Spinath, B., & Kadmon, M. (2012). Measuring teaching effectiveness: Correspondence between students’ evaluations of teaching and different measures of student learning. Research in Higher Education, 53(8), 888–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strelan, P., Osborn, A., & Palmer, E. (2020). The flipped classroom: A meta-analysis of effects on student performance across disciplines and education levels. Educational Research Review, 30, 100314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swart, W., & Wuensch, K. L. (2016). Flipping quantitative classes: A triple win. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 14(1), 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science, 12(2), 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K. S. (2019). Experimental research into teaching innovations: Responding to methodological and ethical challenges. Studies in Science Education, 55(1), 69–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, A., & Powell, P. (2020). Re-imagining the MBA: An arts-based approach. Higher Education Pedagogies, 5(1), 148–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J. N., & Rísquez, A. (2020). Using cluster analysis to explore the engagement with a flipped classroom of native and non-native English-speaking management students. The International Journal of Management Education, 18(2), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy-value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B., Horner, C., & Allen, S. (2019). Flipped vs. traditional teaching perspectives in a first year accounting unit: An action research study. Accounting Education, 28(4), 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, M. H. (2020). Integrating data analysis into an introductory macroeconomics course. International Review of Economics Education, 33, 100176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T. H., Ip, E. J., Lopes, I., & Rajagopalan, V. (2014). Pharmacy students’ performance and perceptions in a flipped teaching pilot on cardiac arrhythmias. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 78(10), 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiu, Y., & Thompson, P. (2020). Flipped university class: A study of motivation and learning. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 19, 41–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, P., Chen, Y., Nie, W., Wang, Y., Song, T., Li, H., Li, J., Yi, J., & Zhao, L. (2019). The effectiveness of a flipped classroom on the development of Chinese nursing students’ skill competence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurse Education Today, 80, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamarik, S. (2019). Flipping the classroom and student learning outcomes: Evidence from an international economics course. International Review of Economics Education, 31, 100163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X., Li, J., & Xing, B. (2018). Behavioral patterns of knowledge construction in online cooperative translation activities. The Internet and Higher Education, 36, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, R. M., & Baydas, O. (2017). An examination of undergraduates’ metacognitive strategies in pre-class asynchronous activity in a flipped classroom. Educational Technology Research and Development, 65(6), 1547–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, H. (2016). Perceived usefulness of “flipped learning” on instructional design for elementary and secondary education: With focus on pre-service teacher education. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 6(6), 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Weekly Learning Subjects | Course Assessments |

|---|---|

|

|

| Subscale Item | Factor Loading | Subscale Item | Factor Loading | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | ||

| Perceived usefulness of OFC | Perceived learning | ||||

| 1. On-line materials increased my interest in the course. | 0.82 | 0.35 | 1. I learn more from the flipped classroom over traditional (lecture-based) classes. | 0.39 | 0.88 |

| 2. On-line materials had a good fit to in-class lectures. | 0.84 | 0.48 | 2. I feel that flipped classroom is a more effective way than the traditional (lecture-based) method to learn OB concepts, theories and principles. | 0.43 | 0.86 |

| 3. On-line materials enhanced the effectiveness of in-class lectures. | 0.81 | 0.38 | 3. Flipped classroom greatly enhances my understanding of OB concepts, theories and principles. | 0.42 | 0.82 |

| 4. Watching learning module videos posted on Blackboard greatly enhanced my understanding of course contents. | 0.77 | 0.42 | 4. My learning in the flipped classroom has helped my personal development. | 0.43 | 0.68 |

| 5. Reviewing narrated PowerPoints posted on Blackboard greatly enhanced my understanding of course contents. | 0.66 | 0.52 | 5. I can apply the knowledge acquired in the flipped classroom to my work or other non-class related activities. | 0.46 | 0.59 |

| 6. Completing practice quizzes posted on Blackboard prior to coming to class greatly enhanced my understanding of course contents. | 0.56 | 0.32 | |||

| Perceived usefulness of IFC | Perceived skills development | ||||

| 1. Listening to the instructor reviewing information about selected topics in the mini lectures greatly enhanced my learning of course materials. | 0.64 | 0.65 | 1. Flipped classroom enabled me to apply OB theories to analyze real-world issues and problems | 0.81 | 0.43 |

| 2. Grouping up with classmates to discuss questions posed in class greatly enhanced my learning of course materials. | 0.51 | 0.82 | 2. Flipped classroom provided me opportunities to think and behave ethically. | 0.76 | 0.39 |

| 3. Working on assignments/exercises in class greatly enhanced my learning of course materials. | 0.44 | 0.85 | 3. Flipped classroom enabled me to analyze the impact of individual and team behaviours on organizational productivity. | 0.80 | 0.44 |

| 4. Studying cases in class greatly enhanced my learning of course materials. | 0.40 | 0.86 | 4. Flipped classroom enabled me to synthesize information to make decisions | 0.80 | 0.34 |

| 5. Flipped classroom helped me develop the ability to plan and manage my own work. | 0.83 | 0.52 | |||

| 6. Flipped classroom helped me develop the ability to work as a team member. | 0.63 | 0.38 | |||

| Eigenvalue | 4.90 | 1.22 | Eigenvalue | 5.15 | 1.50 |

| % variance explained | 48.99 | 12.24 | % variance explained | 46.84 | 13.63 |

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 0.48 | 0.50 | |||||||

| 2. Learning habits | 2.73 | 0.74 | −0.39 ** | ||||||

| 3. Perceived usefulness of OFC | 3.22 | 0.57 | 0.10 | ||||||

| 4. Perceived usefulness of IFC | 3.23 | 0.59 | 0.04 | −0.19 | −0.60 ** | ||||

| 5. Pre-class preparation | 1.51 | 1.12 | 0.26 * | −0.21 | 0.26 * | 0.26 * | |||

| 6. In-class attendance | 2.78 | 0.57 | 0.28 * | −0.29 * | −0.05 | 0.10 | −0.07 | ||

| 7. Perceived learning | 3.07 | 0.67 | 0.14 | −0.16 | 0.73 ** | 0.52 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.05 | |

| 8. Perceived skills development | 3.11 | 0.74 | 0.16 | −0.17 | 0.69 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.34 ** | −0.14 | 0.61 ** |

| Dependent Variables | Pre-Class Preparation | In-Class Participation | Perceived Learning | Skills Development | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | |

| Control variables | |||||||

| Gender | 0.28 * | 0.29 * | 0.08 * | ||||

| Learning Habits | −0.16 | −0.16 | −0.17 | −0.17 | |||

| Model F Value | 6.29 * | 7.06 * | 7.03 * | 1.55 | 1.55 | 2.07 | 2.07 |

| R2 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Independent variables | |||||||

| Perceived Usefulness of OFC | 0.24 * | ||||||

| Perceived Usefulness of IFC | 0.09 | ||||||

| Pre-Class Preparation | −0.16 | 0.31 * | 0.26 * | ||||

| In-Class Participation | 0.02 | −0.21 | |||||

| Model F Value | 5.60 ** | 3.84 * | 4.60 * | 3.90 * | 0.77 | 3.50 * | 2.48 |

| R2 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.07 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.09 | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, G. Effects of a Flipped Classroom College Business Course on Students’ Pre-Class Preparation, In-Class Participation, Learning, and Skills Development. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 301. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080301

Wang G. Effects of a Flipped Classroom College Business Course on Students’ Pre-Class Preparation, In-Class Participation, Learning, and Skills Development. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(8):301. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080301

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Gordon. 2025. "Effects of a Flipped Classroom College Business Course on Students’ Pre-Class Preparation, In-Class Participation, Learning, and Skills Development" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 8: 301. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080301

APA StyleWang, G. (2025). Effects of a Flipped Classroom College Business Course on Students’ Pre-Class Preparation, In-Class Participation, Learning, and Skills Development. Administrative Sciences, 15(8), 301. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080301