Determinants of Future Intentions in a Virtual Career: The Role of Brand Variables

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Brand-Consumer Congruence: Evolution and Applications in Consumer Behaviour

2.1.1. Evolution of the Concept of Congruence and Its Impact on Consumer Behaviour

2.1.2. New Perspectives on Congruence Research

2.1.3. Congruence in the Context of Sport

2.2. Trust in Consumer Behaviour

2.2.1. Trust and Relationship Marketing

2.2.2. Trust in the Business and Inter-Organizational Context

2.2.3. Trust in Sport and Its Relationship with Engagement, Satisfaction and WOM

2.3. Commitment to the Brand

2.3.1. Dimensions of Engagement: Assessment and Emotional Connection

2.3.2. Engagement and Switching Costs: The “Dark Side” of Relationship Marketing

2.3.3. Congruence, Trust and Commitment in Sporting Events

2.3.4. Relationship Between Commitment, Trust and Satisfaction

2.3.5. Engagement in Sport: Impact on the Recommendation

2.4. Satisfaction

2.4.1. Conceptualization and Theories of Satisfaction

2.4.2. Satisfaction and Marketing

2.4.3. Satisfaction in Virtual and Technologically Mediated Sporting Events

2.4.4. Relationship of Satisfaction with Trust, Commitment and WOM

2.4.5. Satisfaction in the Sport Context

2.5. Future Intentions—WOM: Concepts and Theories

2.5.1. Relationship Between WOM and Marketing

2.5.2. Relationship of WOM to Congruence, Commitment, Trust and Satisfaction

2.5.3. WOM and Future Intentions in the Sport Context

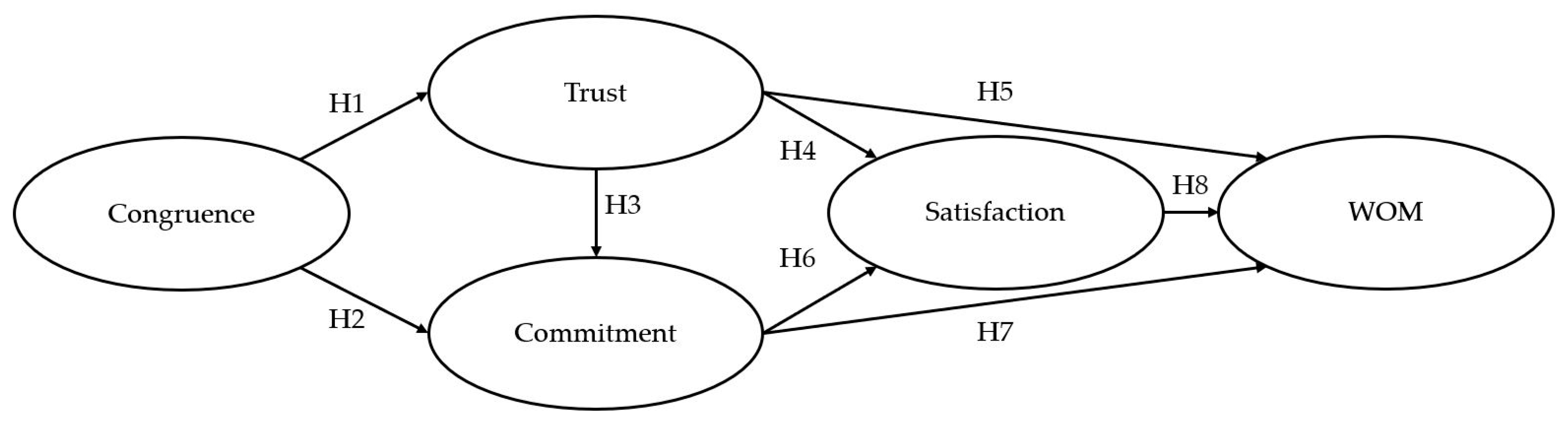

2.5.4. Hypothesis and Structural Model

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample

3.2. Instrument

3.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

4.2. Structural Model

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Implications, Limitations and Future Lines of Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akoglu, H. E., & Özbek, O. (2021). The effect of brand experiences on brand loyalty through perceived quality and brand trust: A study on sports consumers. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 34(10), 2130–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayrak, T., & Caber, M. (2015). Prioritisation of the hotel attributes according to their influence on satisfaction: A comparison of two techniques. Tourism Management, 46, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alguacil, M., Parra-Camacho, D., & Mundina, C. (2019). Brand personality for loyalty enhancement in sport services: The role of congruence. SPORT TK-EuroAmerican Journal, 8(1), 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso Dos Santos, M., Aguado Berenguer, S., Calabuig Moreno, F., & Alguacil, M. (2024a). Predicting loyalty and word-of-mouth at a sports event through a structural model and posteriori unobserved segmentation. Event Management, 28(3), 401–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso Dos Santos, M., & Calabuig, F. (2018). Assessing the effectiveness of sponsorship messaging: Measuring the impact of congruence through electroencephalogram. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 19(1), 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso Dos Santos, M., Calabuig Moreno, F., & Crespo-Hervás, J. (2019). Influence of perceived and effective congruence on recall and purchase intention in sponsored printed sports advertising: An eye-tracking application. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 20(4), 617–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso Dos Santos, M., Torres-Moraga, E., Calabuig Moreno, F., & Llanos Contreras, O. (2024b). Self-reported and electroencephalogram responses to evaluate sponsorship congruence efficacy. Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics, 17(1), 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amenuvor, F. E., & Tark, L. H. (2020). The effect of pre-purchase WOM seeking behavior on the WOM intention. Journal of Marketing Studies, 28(2), 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Amor, J. S., Alguacil, M., & Gómez-Tafalla, A. M. (2022). Gender influence on brand recommendation at an esports event. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 22(1), 231–238. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, J. (2019, July 16). The state of running 2019. International Association of Athletics Federations. Available online: https://runrepeat.com/state-of-running (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, D., Coelho, P. S., & Machás, A. (2004). The role of communication and trust in explaining customer loyalty: An extension to the ECSI model. European Journal of Marketing, 38(9/10), 1272–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S., & Chaudhuri, B. R. (2022). Brand love and party preference of young political consumers (voters). International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 19(3), 475–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bari, M. W., & Shahzadi, I. (2022). Employee-based brand equity and factors of employee-brand association. In Antecedents and outcomes of employee-based brand equity (pp. 1–15). IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, H. S. (1960). Notes on the concept of commitment. American Journal of Sociology, 66(1), 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biscaia, R., Correia, A., Ross, S., & Rosado, A. (2014). Sponsorship effectiveness in professional sport: An examination of recall and recognition among football fans. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 16(1), 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biscaia, R., Yoshida, M., & Kim, Y. (2023). Service quality and its effects on consumer outcomes: A meta-analytic review in spectator sport. European Sport Management Quarterly, 23(3), 897–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitner, M. J. (1990). Evaluating service encounters: The effects of physical surroundings and employee responses. The Journal of Marketing, 54, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, J. L. H. (2009). The process of customer engagement: A conceptual framework. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 17(1), 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research, 21(2), 230–258. [Google Scholar]

- Buenos Aires Herald. (2023). Buenos Aires: Marathon the fastest 42k in Latin America takes place this weekend. Available online: https://www.buenosairesherald.com (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Caceres, R. C., & Paparoidamis, N. G. (2007). Service quality, relationship satisfaction, trust, commitment and business-to-business loyalty. European Journal of Marketing, 41(7/8), 836–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabuig, F., Mundina, J., & Crespo, J. (2010). Eventqual: A measure of the quality perceived by spectators of sporting events. Retos. New Trends in Physical Education, Sport and Recreation, 18, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Calabuig, F., Prado-Gascó, V., Núñez-Pomar, J., & Crespo-Hervás, J. (2021). The role of the brand in perceived service performance: Moderating effects and configurational approach in professional football. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 165, 120537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardozo, R. N. (1965). An experimental study of customer effort, expectation, and satisfaction. Journal of Marketing Research, 2(3), 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, C. B., & Armario, E. M. (1999). Relational marketing. ESIC. [Google Scholar]

- Celestino, A., & Biencinto, C. (2012). External customer satisfaction in fitness organisations. Empirical study in centres in the community of Madrid. Motricidad. European Journal of Human Movement, 29, 115–132. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, A., & Adam, M. R. R. R. (2024). The impacts of corporate-brand credibility, corporate-brand origin, and self-image congruence on purchase intention: The case of PT Mustika ratu TBK Indonesia. In 5th International Conference on Global Innovation and Trends in Economy 2024 (INCOGITE 2024) (pp. 477–490). Atlantis Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzopoulou, E., & Tsogas, M. (2017). The role of emotions to brand attachment and brand attitude in a retail environment: An extended abstract. In M. Stieler (Ed.), Creating marketing magic and innovative future marketing trends. Developments in marketing science: Proceedings of the academy of marketing science (pp. 43–47). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Chelladurai, P., & Chang, K. (2000). Targets and standards of quality in sport services. Sport Management Review, 3(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. L., & Wang, S. W. (2021). The influence of brand positioning and event marketing on brand loyalty-The mediation roles of brand identification and brand personality: The case of spectator sport. Journal of Business Administration, 46(4), 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. S., & Zhang, J. J. (2025). Market demand for metaverse-based sporting events: A mixed-methods approach. Sport Management Review, 28(1), 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Wang, L., & Liu, X. (2022). The impact of brand satisfaction on electronic word-of-mouth intention: The mediating role of brand commitment. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 39(5), 725–739. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhary, K., Crockett, Z., Chua, J., & Soo Hoo, J. (2024). Exploring the relationship between running-related technology use and running-related injuries: A cross-sectional study of recreational and elite long-distance runners. Healthcare, 12(6), 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K. S., Goebert, C., & Johnson, J. D. (2025). Sport spectatorship in a virtual environment: How sensory experiences impact consumption intentions. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 26(2), 305–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claver, E., Llopis, J., & Tarí, J. J. (1999). Calidad y dirección de empresas. Civitas. [Google Scholar]

- Cuesta-Valiño, P., Loranca-Valle, C., Núñez-Barriopedro, E., & Penelas-Leguía, A. (2023). Model based on service quality, satisfaction and trust, the antecedents of federated athletes’ happiness and loyalty. Journal of Management Development, 42(6), 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawar, N., & Pillutla, M. M. (2000). Impact of product-harm crises on brand equity: The moderating role of consumer expectations. Journal of Marketing Research, 37(2), 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dees, W., Bennett, G., & Ferreira, M. (2010). Personality fit in NASCAR: An evaluation of driver-sponsor congruence and its impact on sponsorship effectiveness outcomes. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 19(1), 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Deheshti, M., Adabi Firouzjah, J., & Alimohammadi, H. (2016). The relationship between brand image and brand trust in sporting goods consumers. Annals of Applied Sport Science, 4(3), 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJong, A. F., Fish, P. N., & Hertel, J. (2021a). Running behaviors, motivations, and injury risk during the COVID-19 pandemic: A survey of 1147 runners. PLoS ONE, 16(2), e0246300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJong, M., Brenner, J., & Fogg, L. (2021b). Virtual races and digital participation: Engagement patterns in mass sporting events. Journal of Sport Management, 35(4), 354–367. [Google Scholar]

- DeJong Lempke, A. F., & Hertel, J. (2022). Influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on running behaviors, motives, and running-related injury: A one-year follow-up survey. PLoS ONE, 17(3), e0264361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Ballester, E., & Munuera-Alemán, J. L. (2012). Does brand trust matter to brand equity? Journal of Product & Brand Management, 20(3), 156–172. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y., Wang, X., & Li, D. (2025). How does brand authenticity influence brand loyalty? Exploring the roles of brand attachment and brand trust. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 37(5), 1255–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desbordes, M., & Falgoux, J. (2006). Management and organization of a sporting event. Inde. [Google Scholar]

- Dolich, I. J. (1969). Congruence between self-image and product brands. Journal of Marketing Research, 6(1), 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doney, P. M., & Cannon, J. P. (1997). An examination of the nature of trust in buyer-seller relationships. Journal of Marketing, 61(2), 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Donio, J., Massari, P., & Passiante, P. (2006). Customer satisfaction and loyalty in a digital environment: An empirical test. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 23(7), 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorado, A. (2006). Análisis de la satisfacción de los usuarios: Hacia un nuevo modelo de gestión basado en la calidad para los servicios deportivos municipales. Economic and Social Council of Castilla-La Mancha. [Google Scholar]

- Du, J., Chen, M. Y., & Wu, Y. F. (2020). The effects of social media on sporting event satisfaction and word of mouth communication: An empirical study of a mega sports event. Information, 11(10), 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, F. R., Schurr, P. H., & Oh, S. (1987). Developing buyer-seller relationships. Journal of Marketing, 51(2), 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, Y., & Hosany, S. (2006). Destination personality: An application of brand personality to tourism destinations. Journal of Travel Research, 45(2), 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elasri Ejjaberi, A., Triadó i Ivern, X. M., & Aparicio Chueca, M. (2015). Customer satisfaction in municipal sports centres in Barcelona. Apunts. Educació Física i Esports, 119(1), 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elasri Ejjaberi, A., Triadó i Ivern, X. M., & Chueca, P. A. (2013). Evolution of customer satisfaction factors in sports centres between 1996 and 2013: How have users’ perceptions changed? Discovering new horizons in management: XXVII AEDEM Annual Congress (p. 96). Escuela Superior de Gestión Comercial y Marketing, ESIC. [Google Scholar]

- Ferro-Soto, C., Padín, C., Svensson, G., & Høgevold, N. M. (2024). The sequential logic of quality constructs in sales business relationships: Model and findings. International Journal of Procurement Management, 19(4), 473–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Row, Peterson & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Filo, K., Funk, D. C., & Alexandris, K. (2008). Exploring the role of brand trust in the relationship between brand associations and brand loyalty in sport and fitness. International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing, 3(1–2), 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C. (1992). A national customer satisfaction barometer: The Swedish experience. Journal of Marketing, 56(1), 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, S., Dobscha, S., & Mick, D. (1998). Preventing the premature death of relationship marketing. Harvard Business Review, 76(1), 42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton, G. (2003). When does commitment lead to loyalty? Journal of Service Research, 5(4), 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullerton, G. (2005). How commitment both enables and undermines marketing relationships. European Journal of Marketing, 39(11/12), 1372–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fernández, J., Gálvez-Ruiz, P., Fernández-Gavira, J., & Vázquez-Fernández, E. (2021). The role of brand commitment and satisfaction in predicting word-of-mouth intentions in fitness centers. European Sport Management Quarterly, 21(4), 567–586. [Google Scholar]

- Geyskens, I., Steenkamp, J. B., & Kumar, N. (1998). Generalizations about trust in marketing channel relationships using meta-analysis. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 15(3), 223–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyskens, I., Steenkamp, J. B., Scheer, L. K., & Kumar, N. (1996). The Effects of trust and interdependence on relationship commitment: A transatlantic study. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 13, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese, J. L., & Cote, J. A. (2000). Defining consumer satisfaction. Academy of Marketing Science Review, 1(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Grace, D., & O’Cass, A. (2005). Service branding: Consumer verdicts on service brands. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 12(2), 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulavani, S. S., Dai, S., Du, J., Sato, M., & Newman, J. (2025). Associative personalities: Investigating the impact of gender personality congruence between sport brands and individuals on life satisfaction. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullupunar, H., & Gulluoglu, O. (2013). Voter’s loyalty to a political party in terms of organizational commitment factor: A research on voters living in big cities in Turkey. E-Journal of New World Sciences Academy (NWSA), 8(1), 82–99. [Google Scholar]

- Gundlach, G. T., Achrol, R. S., & Mentzer, J. T. (1995). The structure of commitment in exchange. Journal of Marketing, 59(1), 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D., & Kendall, K. W. (2006). Hosting mega events: Modeling locals’ support. Washington State University. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Pearson-Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Hallmann, K., & Breuer, C. (2010). Image fit between sport events and their hosting destinations from an active sport tourist perspective and its impact on future behaviour. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 15(3), 215–237. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H., & Hyun, S. S. (2013). Image congruence and relationship quality in predicting switching intention: Conspicuousness of product use as a moderator variable. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 37(3), 303–329. [Google Scholar]

- Hee Kwak, D., & Kang, J. H. (2009). Symbolic purchase in sport: The roles of self-image congruence and perceived quality. Management Decision, 47(1), 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helsen, K., Derom, I., Corthouts, J., Bosscher, V. D., Willem, A., & Scheerder, J. (2022). Participatory sport events in times of COVID-19: Analysing the (virtual) sport behaviour of event participants. European Sport Management Quarterly, 22(1), 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T. (2004). Customer orientation of service employees: Its impact on customer satisfaction, commitment and retention. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 15(5), 460–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hightower, R., Brady, M. K., & Baker, T. L. (2002). Investigating the role of the physical environment in hedonic service consumption: An exploratory study of sporting events. Journal of Business Research, 55(9), 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, H. H., Monaghan, P. G., Strunk, K. K., Paquette, M. R., & Roper, J. A. (2021). Changes in training, lifestyle, psychological and demographic factors, and associations with running-related injuries during COVID-19. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 3, 637516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, J. A. (1989). Consumer behavior in marketing strategy. Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, J. A., & Sheth, J. N. (1969). The theory of buyer behavior. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., & Chiu, W. (2024). Let’s run green! Impact of runners’ environmental consciousness on their green perceived quality and supportive intention at participatory sport events. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 25(3), 541–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, I. J. (2022). I trust friends before I trust companies: The mediation of WOM and brand love on psychological contract fulfilment and repurchase intention. Management Matters, 19(2), 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, G., & James, J. (2004). Service quality dimensions: An examination of Grönroos’s service quality model. Managing Service Quality, 14(4), 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplanidou, K. (2010). Active sport tourists: Sport event image considerations. Tourism Analysis, 15(3), 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenning, P. (2008). The influence of general trust and specific trust on buying behaviour. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 36(6), 461–476. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J., Song, H., & Lee, S. (2018). Extrovert and lonely individuals’ social TV viewing experiences: A mediating and moderating role of social presence. Mass Communication and Society, 21(1), 50–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y. J., & Kim, Y. K. (2014). Determinants of consumers’ attitudes toward a sport sponsorship: A tale from college athletics. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 26(3), 185–207. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, J., & Lee, Y. (2019). Sponsor-event congruence effects: The moderating role of sport involvement and mediating role of sponsor attitudes. Sport Management Review, 22(2), 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N., Hibbard, J. D., & Stern, L. W. (1994). The nature and consequences of marketing channel intermediary commitment (pp. 94–115). Marketing Sciences Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, M. Y., Fotiadis, A. K., Abu-ElSamen, A., & Beede, P. (2022). Analysing the effect of membership and perceived trust on sport events electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) intention. Tourism Recreation Research, 47(1), 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M., & Brisoux, J. E. (1989). Incorporating competition into consumer behavior models: The case of the attitude-intention relationship. Journal of Economic Psychology, 10(3), 343–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, S. J. (1959). Symbols for Sale. Harvard Business Review, 34(4), 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y., Zhang, C., Shelby, L., & Huan, T. C. (2022). Customer self-image congruence and brand preference: A moderated mediation model of self-brand connection and self-motivation. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 31(5), 798–807. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C. W., Wang, W., Gao, G., & Agarwal, R. (2024). The value of virtual engagement: Evidence from a running platform. Management Science, 70(9), 6179–6201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorens, F. J., & Fuentes, M. (2000). Total quality. Fundamentos e Implantación. Pirámide. [Google Scholar]

- Luna-Arocas, R., & Mundina, J. (1998). The strategic marketing of sport: Satisfaction, motivation and expectations. Revista de Psicología del Deporte, 7(2), 171–177. [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum, R. C., & Austin, J. T. (2000). Applications of structural equation modeling in psychological research. Annual Review of Psychology, 51(1), 201–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisam, S., & Mahsa, R. D. (2016). Positive word of mouth marketing: Explaining the roles of value congruity and brand love. Journal of Competitiveness, 8(1), 19–37. [Google Scholar]

- Mal, D., Wolf, E., Döllinger, N., Wienrich, C., & Latoschik, M. E. (2023). The impact of avatar and environment congruence on plausibility, embodiment, presence, and the proteus effect in virtual reality. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 29(5), 2358–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano, M. J. L., & Ruiz, J. L. C. (2023). Socio-educational potential of participation in popular races: A systematic review. In Metodologías activas e innovación docente para una educación de calidad (pp. 875–885). Dykinson. [Google Scholar]

- Marcu, D., Tudor, V., Borz, C., & Mărgărit, I. (2021). Conducting sports street running events in virtual and physical space: A comparative study. Marketing—From Information to Decision, 13(1), 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Cevallos, D., Alguacil, M., Calabuig, F., & Duclos-Bastías, D. (2024). Brand perception and its relationships to satisfaction with a virtual sporting event. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 25(5), 1059–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Cevallos, D., Alguacil, M., & Calabuig Moreno, F. (2020). Influence of brand image of a sports event on the recommendation of its participants. Sustainability, 12(12), 5040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, L. (2022). Adapting practice during the COVID-19 pandemic: Experiences, learnings, and observations of a music therapist running virtual music therapy for trafficked women. Approaches: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Music Therapy, 14(1), 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medellín Marathon. (2024). Maratón Medellín the pioneer of street events in Colombia 30 years of glory and growth for local athletics. Available online: https://maratonmedellin.com/blogs/comunicados-de-prensa-maraton-medellin/maraton-medellin-la-pionera-de-las-pruebas-de-calle-en-colombia-30-anos-de-gloria-y-crecimiento-para-el-atletismo-local#:~:text=La%20Marat%C3%B3n%20Medell%C3%ADn%20naci%C3%B3%20hace,con%20una%20carrera%20de%2042K (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Meenaghan, T. (2001). Understanding sponsorship effects. Psychology & Marketing, 18(2), 95–122. [Google Scholar]

- Moliner, B., & Fuentes, M. (2011). Causes and consequences of consumer dissatisfaction with external attributions. Cuadernos de Gestión, 11(1), 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, C., Zaltman, G., & Deshpande, R. (1992). Relationships between providers and users of market research: The dynamics of trust within and between organizations. Journal of Marketing Research, 29(3), 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, V., & Hernández, A. (2004). Quality and satisfaction in services: Conceptualisation. Available online: http://efdeportes.com/ (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Morales, V., Hernández-Mendo, A., & Blanco, Á. (2009). Quality assessment in sport organisations: Adaptation of the SERVQUAL model. Journal of Sport Psychology, 18(2), 0137–0150. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, T., Veera Raghavan, D. R., & Jayapal, J. (2024). How does channel integration quality promote omnichannel customer citizenship behavior? The moderating role of the number of channels used and gender. Kybernetes, 53(10), 3133–3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natasiah, U. (2024). Brand image, brand trust, and brand ambassador on purchase decisions of Shopee e-commerce users in Pekanbaru city. Jurnal Manajemen Bisnis, 11(1), 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newland, B. L., & Yoo, J. J. E. (2021). Active sport event participants’ behavioural intentions: Leveraging outcomes for future attendance and visitation. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 27(1), 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D. T., Le, H. T., & Pham, T. T. (2021). Brand congruence and its impact on brand trust and loyalty: Evidence from sports fans. International Journal of Sport Marketing & Sponsorship, 22(3), 445–460. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, D. T., Nguyen, T. T. H., Nguyen, K. O., Pham, T. T. H., & Nguyen, T. H. (2023). Brand personality and revisit intention in the hotel industry: The mediating role of tourist self-image congruence. Tourism and Hospitality Management, 29(2), 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okayasu, I., Nogawa, H., Casper, J. M., & Morais, D. B. (2016). Recreational sports event participants’ attitudes and satisfaction: Cross-cultural comparisons between runners in Japan and the USA. Managing Sport and Leisure, 21(3), 164–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R. (1981). Measurement and evaluation of the satisfaction process in retail settings. Journal of Retailing, 57, 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, R. (1997). Satisfaction: A behavioral perspective on the consumer. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, R. (2010). Consumer brand loyalty. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, S. O., Wilcox, J., & Olsson, U. (2005). Consequences of ambivalence on satisfaction and loyalty. Psychology & Marketing, 22(3), 247–269. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, C. A., & Chatman, J. (1986). Organizational commitment and psychological attachment: The effects of compliance, identification, and internalization on prosocial behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, P. L., & Phua, J. (2021). Connecting sponsor brands through sports competitions: An identity approach to brand trust and brand loyalty. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, 11(2), 164–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, D., Kaplanidou, K., & Papacharalampous, N. (2016). Sport event-sponsor fit and its effects on sponsor purchase intentions: A non-consumer perspective among athletes, volunteers and spectators. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 31(2), 247–259. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, B., Hawke, F., Spink, M., Sadler, S., Hawes, M., Callister, R., & Chuter, V. (2022). Biomechanical and musculoskeletal measurements as risk factors for running-related injury in non-elite runners: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sports Medicine-Open, 8(1), 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phua, J. (2024). Integrating digital technology into marathon races with a mobile application: An empirical investigation. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 6(2), 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino García, G., Aguilar Barajas, I., & Ayala Gaytán, E. A. (2018). The role of trust in collaborative innovation projects. A theoretical-methodological proposal. Economía, Sociedad y Territorio, 18(58), 629–655. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard, M. P., Havitz, M. E., & Howard, D. R. (1999). Analyzing the commitment-loyalty link in service contexts. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 27(3), 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, J. S., Yousaf, A., Itani, M. N., & Singh, A. (2021). Sports celebrity personality and purchase intention: The role of endorser-brand congruence, brand credibility and brand image transfer. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, 11(3), 340–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, R. P., & Arun, C. J. (2021). The effect of sport nostalgia on discrete positive emotions, positive eWOM, and revisit intention of sport tourists. International Journal of Business & Economics, 6(2), 232–248. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, K. (2005). Lovemarks: The future beyond brands. Powerhouse books. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers, S. (2007). Effects of sponsorship congruity on e-sponsors and e-newspapers. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 84(1), 24–39. [Google Scholar]

- Sargeant, A., & Lee, S. (2004). Trust and relationship commitment in the United Kingdom voluntary sector: Determinants of donor behavior. Psychology & Marketing, 21(8), 613–635. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., Raithel, S., & Gudergan, S. P. (2014). In pursuit of understanding what drives fan satisfaction. Journal of Leisure Research, 46(4), 419–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheerder, J., Breedveld, K., & Borgers, J. (Eds.). (2015). Running across Europe: The rise and size of one of the largest sport markets. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Schilke, O., & Lumineau, F. (2023). How organizational is interorganizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 1–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M. J. (1982). Self-concept in consumer behavior: A critical review. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(3), 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M. J. (1986). Self-congruity: Toward a theory of personality and cybernetics. Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Sirgy, M. J., Johar, J. S., Samli, A. C., & Claiborne, C. B. (1997). Self-congruity versus functional congruity: Predictors of consumer behavior. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 25(4), 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiriadou, P., Linsner, A., Hallmann, K., & Hill, B. (2025). Athlete brand congruence as a measure to evaluate brand identity and image fit. Australasian Marketing Journal, 33(1), 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storbacka, K., Strandvik, T., & Gronroos, C. (1994). Managing customer relationship for profit: The dynamics of relationship quality. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 5(5), 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, N., & Reynolds, D. (2017). Effects of brand personality dimensions on consumers’ perceived self-image congruity and functional congruity with hotel brands. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 66, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šegota, T., Chen, N., & Golja, T. (2022). The impact of self-congruity and evaluation of the place on WOM: Perspectives of tourism destination residents. Journal of Travel Research, 61(4), 800–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorakis, N. D., Kaplanidou, K., & Karabaxoglou, I. (2015). Effect of event service quality and satisfaction on happiness among runners of a recurring sport event. Leisure Sciences, 37(1), 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorou, S., Alexandris, K., & Ntovoli, A. (2024). The relationship between sport event experience and psychological well-being: The case of a “sailing marathon”. Challenges: New Trends in Physical Education, Sport and Recreation, (57), 484–493. [Google Scholar]

- Traylor, M. B. (1981). Product involvement and brand commitment. Journal of Advertising Research, 21, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Triantafillidou, A., & Siomkos, G. (2014). Consumption experience outcomes: Satisfaction, nostalgia intensity, word-of-mouth communication, and behavioural intentions. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 31(6/7), 526–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, F. M., & Bui, T. D. (2021). Impact of word of mouth via social media on consumer intention to purchase cruise travel products. Maritime Policy & Management, 48(2), 167–183. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-González, C., & Toro-Jaramillo, I. D. (2022). Trust in organisations: Reflection on its meaning and scope. CEA Journal, 8(18), 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Vegara-Ferri, J. M., López-Gullón, J. M., Valantine, I., Díaz Suárez, A., & Angosto, S. (2020). Factors influencing the tourist’s future intentions in small-scale sports events. Sustainability, 12(19), 8103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vegara-Ferri, J. M., Saura, E. M., López-Gullón, J. O. S. É., Sánchez, G. F. L., & Angosto, S. (2018). The touristic impact of a sporting event attending to the future intentions of the participants. Journal of Physical Education & Sport, 18(3), 1356–1365. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M. C. H. (2017). Investigating the different congruence effects on sports sponsor brand equity. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 18(2), 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waśkowski, Z., & Jasiulewicz, A. (2022). Determinants of the engagement of virtual runs’ participants in the co-creation of customer value during the pandemic. Journal of Education, Health and Sport, 12(5), 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woyo, E., & Nyamandi, C. (2022). Application of virtual reality technologies in the Comrades Marathon as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Development Southern Africa, 39(1), 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, C. K. B., Chan, K. W., & Hung, K. (2007). Multiple reference effects in service evaluations: Roles of alternative attractiveness and self-image congruity. Journal of Retailing, 83(1), 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, M., & James, J. D. (2010). Customer satisfaction with game and service experiences: Antecedents and consequences. Journal of Sport Management, 24(3), 338–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, L., & Hon, L. C. (2021). Testing the effects of reputation, value congruence and brand identity on word-of-mouth intentions. Journal of Communication Management, 25(2), 160–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V. A., Berry, L. L., & Parasuraman, A. (1996). The behavioral consequences of service quality. The Journal of Marketing, 60(2), 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C., & Chen, L. (2020). The effect of self-congruity on brand loyalty in sportswear consumption: The moderating role of psychological ownership. International Journal of Sports Marketing & Sponsorship, 21(4), 651–670. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y., Kim, E., & Xing, Z. (2021). Image congruence between sports event and host city and its impact on attitude and behavior intention. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 22(1), 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Statement |

|---|---|

| Congruence (Grace & O’Cass, 2005) | The image of this brand is in accordance (congruent) with my own image. |

| Participating in this race reflects who I am. | |

| People similar to me participate in this race. | |

| The type of person who usually participates in this race is very similar to me. | |

| Trust (Caceres & Paparoidamis, 2007; Donio et al., 2006). | The Medellín Marathon cares about my needs as a customer. |

| I feel that I have full confidence in the activities and services of the Medellín Marathon. | |

| Commitment (Fullerton, 2005; Hennig-Thurau, 2004). | I feel emotionally attached to the Medellín Marathon. |

| The Medellín Marathon means a lot to me. | |

| I feel strongly identified with the Medellín Marathon. | |

| My relationship with the Medellín Marathon is important to me. | |

| If the Medellín Marathon were to cease to exist, it would be a great loss to me. | |

| Satisfaction (Hightower et al., 2002). | I am happy with the experiences I have had in this race. |

| I have been satisfied with my experiences in this race. | |

| I really enjoy participating in this race | |

| WOM (Zeithaml et al., 1996). | I will participate in the Medellin Marathon next year. |

| I will recommend participation in the Medellín Marathon. | |

| I will speak well of the Medellín Marathon to other people if they ask me. |

| Construct | Items | β | FC | AVE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Congruence (F1) | 1 | 0.789 | 0.87 | 0.68 | 0.627 |

| 2 | 0.862 | 0.769 | |||

| 3 | 0.843 | 0.778 | |||

| 4 | 0.756 | 0.623 | |||

| Trust (F2) | 5 | 0.844 | 0.91 | 0.82 | 0.784 |

| 6 | 0.933 | 0.852 | |||

| Commitment (F3) | 7 | 0.896 | 0.95 | 0.84 | 0.812 |

| 8 | 0.925 | 0.869 | |||

| 9 | 0.965 | 0.898 | |||

| 10 | 0.946 | 0.865 | |||

| 11 | 0.787 | 0.523 | |||

| Satisfaction (F4) | 12 | 0.940 | 0.92 | 0.76 | 0.812 |

| 13 | 0.896 | 0.803 | |||

| 14 | 0.866 | 0.645 | |||

| WOM (F5) | 15 | 0.733 | 0.88 | 0.73 | 0.543 |

| 16 | 0.942 | 0.834 | |||

| 17 | 0.898 | 0.776 |

| Hypothesis | β | T Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Congruence–Trust | 0.61 | 22.30 ** | Supported |

| H2: Congruence–Commitment | 0.52 | 12.07 ** | Supported |

| H3: Trust–Commitment | 0.33 | 7.95 ** | Supported |

| H4: Trust–Satisfaction | 0.61 | 13.99 ** | Supported |

| H5: Trust–WOM | 0.21 | 13.95 ** | Supported |

| H6: Commitment–Satisfaction | 0.26 | 5.87 ** | Supported |

| H7: Commitment–WOM | 0.20 | 6.760 ** | Supported |

| H8: Satisfaction–WOM | 0.49 | 10.80 ** | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martínez-Cevallos, D.; Calabuig, F.; Duclos-Bastías, D.; Crespo-Hervás, J.; Alguacil, M. Determinants of Future Intentions in a Virtual Career: The Role of Brand Variables. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 269. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15070269

Martínez-Cevallos D, Calabuig F, Duclos-Bastías D, Crespo-Hervás J, Alguacil M. Determinants of Future Intentions in a Virtual Career: The Role of Brand Variables. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(7):269. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15070269

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartínez-Cevallos, Daniel, Ferran Calabuig, Daniel Duclos-Bastías, Josep Crespo-Hervás, and Mario Alguacil. 2025. "Determinants of Future Intentions in a Virtual Career: The Role of Brand Variables" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 7: 269. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15070269

APA StyleMartínez-Cevallos, D., Calabuig, F., Duclos-Bastías, D., Crespo-Hervás, J., & Alguacil, M. (2025). Determinants of Future Intentions in a Virtual Career: The Role of Brand Variables. Administrative Sciences, 15(7), 269. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15070269