Abstract

This study explores how Human Resource Management (HRM) can help organizations to face the challenges of digital transformation, focusing on reducing digital inequalities and improving employee performance. As digital tools become more important in workplaces, many employees still experience digital exclusion, which affects not only their productivity but also their sense of fairness and inclusion, as well. To investigate these issues, quantitative research was conducted using a structured questionnaire distributed online to employees across EU-based companies. The data were analyzed through PLS-SEM, including IPMA and mediation analysis, to understand the relations between HRM practices, digital skills, and perceptions of organizational justice. The findings show that HRM strategies have a significant impact on bridging the digital divide, especially by promoting digital adaptability and supporting inclusive work environments. Inclusion was also found to mediate the relation between HRM and employee performance. This research offers practical suggestions, like using Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) to monitor digital participation and encouraging continuous learning. The study adds value by connecting digital empowerment with HRM policies in a way that supports both organizational efficiency and equality. Future research could focus on specific sectors or use longitudinal data to better capture how digital inclusion develops over time.

1. Introduction

Creating equal job opportunities in digitally changing environments is nowadays a critical matter both for businesses and public policies. This paper faces the digital divide as an invisible but important challenge in strategic human resource management (HRM), aiming to give empowerment to all employees, no matter their digital skills. This approach is not only about access to technology, but also about putting HRM practices that improve resilience, inclusion, and adaptability of human capital in an ever-changing organizational framework (Park, 2017; Szabó, 2024).

In the context of this study, the “digital divide” refers to the multidimensional inequalities in access, skills, and outcomes related to digital technologies among employees. These disparities are shaped not only by technical availability but also by age, gender, educational background, and job position within organizations. This broader approach is adopted to explore how such differences influence participation, perceived fairness, and performance in digitally evolving workplaces (Ragnedda, 2018; Robinson, 2015).

Digital divide arises not only from material limits, but mostly from inequalities in access to digital capital, meaning the ability to get and use digital resources for social and professional progress (Grzenkowicz, 2025; Ragnedda, 2018). Therefore, organizations must adopt HRM strategies that help employees to grow their digital skills and also break the social and cultural parts of exclusion (Patole et al., 2025; Valli, 2025). Even if the digital divide is more recognised today as a factor for equality, literature still sees this problem in separate ways. Some studies focus on technological inclusion (Cain & Coldwell-Neilson, 2024) and others on skills development (Van Laar et al., 2017), without seeing the complex dynamics between digital exclusion, organizational justice, and how efficient HR practices are. This paper aims to cover this research gap by showing how inequalities in digital access inside organizations can affect work performance and the design of participative HRM strategies.

Muzumdar (2025) claims that organizational justice, like the function of processes, communication, and resource sharing, is the basis for including workers who are marginalized (Muzumdar, 2025). But Kim (2025) noticed that justice, if it is not inside HRM practices with a focus on adaptability and working with uncertainty, cannot answer the needs of precarious employees (Kim, 2025). In this way, job crafting theory is getting richer through the organizational justice view, showing new ways for inclusion. The innovation of this paper is the connection of these theories with real data about how digital exclusion is impacting organizational performance. Špadina and Ljubić (2024) show that digital bullying, like not giving access to work information, destroys not only trust but also team spirit in organizations. So, HRM cannot be neutral anymore to digital practices, but must make policies that stop marginalization and help equal participation (Špadina & Ljubić, 2024).

Wu et al. (2025) show that digital finance, with innovation and entrepreneurship, can reduce economic inequalities inside cities (Wu et al., 2025). Likewise, HRM with digital tools and inclusive logic can make for better performance and resilience (Priyamedha et al., 2025; Chatterjee et al., 2021). To understand these connections, leadership must be active as a catalyst for inclusion, creating a digital culture (Frosch et al., 2024; Goodwin et al., 2024). Also, this paper gives attention to how HR strategy is mediating the change from digital divide to digital empowerment. Meena and Santhanalakshmi (2025) show that digital literacy is connected directly with employee performance and engagement, and Katsaros (2025), with Schraub (2011), speak about emotional regulation and flexibility when organizations must adapt to changes. These skills are basic elements for digital resilience (Katsaros, 2025; Meena & Santhanalakshmi, 2025; Schraub, 2011).

The contribution of this work is making a multi-level research framework, which sees HRM under technological equality, organizational justice, and how HRM practices work efficiently. This framework does not see these factors alone, but as connected things that influence the participation and productivity of employees. With empirical data and theory, this paper aims to give practical proposals for making digital empowerment better for all groups in an organization, especially for those near technological exclusion. In this way, organizations can have more flexibility and equality when digital changes are happening all the time.

Finally, recent research shows that HRM strategies—such as targeted digital training, equal access to technology, and continuous learning support—not only enhance employees’ digital skills but also contribute to higher job performance and increased organizational inclusion. Improved digital skills enable employees to perform their tasks more efficiently, adapt to technological changes, and participate more fully in workplace processes. At the same time, inclusive HRM policies foster a sense of fairness and belonging, helping to reduce barriers to participation and promote a more equitable workplace climate. The complex interplay between HRM practices, digital skills, employee performance, and inclusion forms the foundation of this study and guides the analysis that follows (Bondarouk & Brewster, 2016; Chatterjee et al., 2021; Meena & Santhanalakshmi, 2025).

Building on this foundation, the aim of this study is to investigate how HRM strategies can effectively bridge the intra-organizational digital divide and enhance employee performance through digital empowerment and inclusion. The motivation stems from the need to address persistent digital inequalities that affect not only individual productivity but also perceptions of fairness and participation in the workplace. While existing literature often isolates technological or HR perspectives, this study offers an integrated approach combining digital skills, HRM practices, and organizational justice. Therefore, the central research question guiding this work is: How can HRM contribute to reducing digital exclusion and fostering inclusive, high-performing work environments in the context of digital transformation?

This study advances literature by integrating multiple theoretical streams—digital divide, organizational justice, and human resource management—into a cohesive framework that explains how HRM practices influence digital empowerment and inclusion in the workplace. Unlike prior research that treats these concepts separately, our approach provides a novel, multi-level perspective that captures the dynamic interplay between technology, organizational processes, and employee experiences. This integrative model not only empirically validates existing constructs but also offers new insights into the mechanisms driving digital inclusion, thereby contributing uniquely to both theory and practice.

Given that previous literature sometimes uses terms such as “digital empowerment”, “digital agency”, “digital influence”, and “digital fluency” interchangeably, this manuscript explicitly defines and distinguishes these concepts to avoid conceptual ambiguity and to maintain consistency throughout the analysis. For conceptual clarity, this study distinguishes the following terms. Digital empowerment refers to the process through which employees acquire not only technical skills but also the confidence and autonomy to leverage digital tools for their professional growth and participation. Digital agency describes the capacity of individuals to make intentional, self-directed choices about how and when to use digital technologies in their work. Digital influence is understood as the ability of individuals or groups to shape organizational processes, decisions, or outcomes through the strategic use of digital platforms and tools. Digital fluency denotes the ease, flexibility, and adaptability with which an individual learns, applies, and integrates new digital technologies in various professional contexts. In this manuscript, the term “digital empowerment” is primarily used, while the other concepts are referenced when specific distinctions are relevant to the analysis (Cain & Coldwell-Neilson, 2024; Passey et al., 2018; Ragnedda et al., 2022; Van Laar et al., 2017).

2. Theoretical Framework

The digital transformation of workplaces brings not only opportunities but also creates important challenges regarding equality, inclusion, and performance. Many recent studies point out that digitalization often reproduces existing social inequalities, especially when organizations do not face these issues in a systematic way. Because of this, understanding the digital divide needs a broader view that connects technology with human resource management (HRM) and also with organizational culture.

2.1. The Digital Divide in the Workplace

Today, the digital divide is not limited to access to ICT infrastructure. It reflects complex inequalities in using digital tools, utilizing skills, and achieving outcomes within organizations. As Szabó (2024) mentions, digital inequality is more related to socio-economic and cognitive factors than technical availability. His analysis identifies three dimensions—structural, cognitive, and motivational—that influence both individual and organizational levels (Szabó, 2024).

For instance, the structural dimension often refers to unequal access to hardware, high-speed internet, or digital tools across different organizational units or job roles. For example, production departments or frontline employees may have more limited access to advanced technologies compared to administrative or managerial staff (Ragnedda, 2018). The cognitive dimension involves differences in digital literacy, problem-solving ability, or self-efficacy; employees with less prior experience or lower confidence in using new systems might struggle to adopt digital workflows or to participate fully in training initiatives (Van Deursen & Helsper, 2015). Lastly, the motivational dimension captures employees’ willingness or perceived relevance to engage with digital technologies, which may be affected by attitudes toward change, age, or perceived career benefits. For example, older employees or those in routine-based roles might not see immediate value in upskilling, thereby reinforcing the digital divide within the workplace (Szabó, 2024).

Within companies, the intra-organizational digital divide refers to unequal access, use, and digital performance among employees, affecting efficiency and innovation (Lu, 2024; Zervas et al., 2024). The differentiation between access, skills, and outcomes—the three levels of the digital divide—is crucial to understanding inequalities in the workplace (Meena & Santhanalakshmi, 2025). Notably, digital exclusion often reflects broader social inequalities (Kostina et al., 2021).

While enough literature adopts a macro or technical view, organizational experiences and cultural factors are frequently neglected (Ng, 2012). However, culture, empowerment, and perceptions of justice play a key role in shaping digital inequalities (Barton & Barton, 2011).

Theoretical perspectives, such as Structuration Theory, explain how workplace routines can reinforce digital gaps (Whittington, 2015), while the Capability Approach highlights the importance of real opportunities for digital empowerment. Digital capital, as introduced by Ragnedda et al. (2022), and its interplay with social capital further illustrate the link between digital skills and workplace equity. Finally, the concept of digital agency underscores the role of employee autonomy and confidence in promoting inclusion (Kostina et al., 2021; Passey et al., 2018; Ragnedda et al., 2022).

The interaction between digital capital and traditional forms of social capital (such as professional networks, trust, and shared norms) significantly shapes employees’ opportunities and advancement within organizations. Research suggests that digital capital—encompassing both digital competencies and access to technology—can enhance or, in some cases, amplify existing social capital, facilitating information sharing, collaboration, and access to organizational resources (Ragnedda, 2018; Ragnedda et al., 2022). Employees with high levels of both digital and social capital are better positioned to leverage digital platforms for career development, build influential networks, and improve job performance (Van Dijk, 2021). Conversely, a lack of digital capital may exacerbate social inequalities, as employees with fewer digital skills or weaker networks may experience limited access to information, reduced visibility, and slower professional progression within the organization.

The workplace digital divide stems from both technical and social factors, such as age, gender, and education (Valli, 2025). Women, especially in male-dominated sectors and other disadvantaged groups, face indirect exclusion from digital opportunities. Organizational hierarchy, training access, and company culture also shape digital skill development, while weak or selective training policies reinforce inequalities, particularly for non-technical staff (Chatterjee et al., 2021; Frosch et al., 2024). Stereotypes and evaluation systems often favor already skilled employees, ignoring different starting points and contributing to “multi-speed workplaces” (Meena & Santhanalakshmi, 2025; Onyekwere, 2024).

This divide restricts participation, career progression, and leadership opportunities for those with fewer digital skills, particularly women and minorities. Training opportunities often benefit those who are already advantaged, thereby widening the existing gap. To create an inclusive workplace, equitable access to learning and skill development is essential (Lu, 2024; Patole et al., 2025).

Most literature conceptualizes the digital divide through technical or socio-economic frameworks, but rarely integrates these within the organizational context. The complex interaction of structural, institutional, and cultural factors remains underexplored in empirical research, especially regarding their daily impact on employee participation and justice. There is a clear need for multidimensional, workplace-centered studies connecting digital exclusion with HR practices, inclusion, and performance (Ragnedda et al., 2022; Szabó, 2024).

As discussed, digital inequality in organizations reflects deeper structural and cultural issues. While literature recognizes this complexity, it often misses how these dynamics operate daily in HRM practices.

Based on this analysis, two research questions arise:

RQ1: How does the intra-organizational digital divide manifest in modern workplaces?

This question explores how digital inequalities appear in daily work, focusing on differences in access, skills, and outcomes.

RQ2: Which organizational factors contribute to the maintenance or intensification of digital exclusion?

This question investigates how structures, culture, and HRM practices can either reduce or worsen digital inequalities among employees.

2.2. HRM Practices for Digital Empowerment

The shift of HRM from administrative to strategic roles is strongly linked to the technological empowerment of employees. HR now actively shapes digital inclusion policies, not just handling routine tasks. Digital HR practices boost empowerment and performance, while adaptability and flexibility gained from digital tools are increasingly vital. Still, unequal access to digital resources and training remains a key barrier to productivity and inclusion (Aggarwal & Stanley, 2025; Ramachandaran et al., 2024).

Digital illiteracy, though often hidden, is a major obstacle to workplace efficiency and equality. HRM must address not only individual but also collective productivity gaps by promoting a culture of lifelong learning, equal access to training, and technological empowerment. Policies focused on digital fairness—such as evaluating real skills and supporting employees with less digital experience—help build a more equitable and digitally mature organization (Meena & Santhanalakshmi, 2025; Sarwar et al., 2024).

A core HRM strategy is employee reskilling and upskilling, aligning skills with the needs of the digital workplace at three levels: training, support, and organizational culture. Flexible training models—such as microlearning and mentoring—help develop digital skills according to individual needs, while the combination of technical and interpersonal training increases overall digital readiness (Jawwad, 2023; Na Ayudhya & Plangsorn, 2024; Rosak-Szyrocka et al., 2024).

At the support level, tailored onboarding and ongoing techniques help employees overcome digital challenges, but the effectiveness of these efforts depends on HRM’s agility and personalized learning. The third level concerns the organizational culture, where continuous learning and participative leadership are promoted, empowering employees to adapt and actively engage in digital transitions (Chatterjee et al., 2021; Frosch et al., 2024).

Nevertheless, barriers, such as organizational inertia and lack of strategic planning, often lead to superficial digital initiatives. Similarly, generic HR interventions that do not address employees’ real needs—like untargeted training seminars—fail to support digital empowerment and engagement (Winarni et al., 2024; Jawwad, 2023).

Structural inequalities, such as unequal training opportunities by job position, further deepen the digital divide within organizations. Resistance to digital change, especially among older or less confident employees, also limits the effectiveness of HRM strategies. Leadership trust and psychological support are essential to overcome technology fear and encourage active employee participation. Addressing these barriers requires a transformation in the organization’s work culture, with an emphasis on inclusion, trust-building, and strengthening employee self-worth (Barton & Barton, 2011; Na Ayudhya & Plangsorn, 2024).

The effectiveness of digital empowerment in HRM depends on employee participation, adaptability, measurable outcomes, and strong leadership. HR practices must flexibly adapt to employee diversity in age, gender, and digital capital (Jawwad, 2023; Ragnedda, 2018).

These strategies should be evaluated with clear metrics—such as digital tool usage, confidence, and productivity—using KPIs and real-time feedback. Strong HR leadership is needed to translate technology initiatives into an organizational culture that supports psychological empowerment and lifelong learning, making digital empowerment a systemic part of the organization (Aggarwal & Stanley, 2025; Rosak-Szyrocka et al., 2024).

Despite significant attention in the literature on HRM’s role in digital transformation, current studies often overlook practical implementation barriers. While the theoretical framework proposed by authors, such as Tariq et al. (2025) and Aggarwal and Stanley (2025), effectively connects digital tools with employee adaptability, limited emphasis is placed on actual organizational barriers (Aggarwal & Stanley, 2025; Tariq et al., 2025). Moreover, the concept of organizational inertia, although widely recognized, is frequently discussed superficially without deep empirical examination of its roots or impacts. Additionally, human resistance as a factor receives less attention compared to structural issues, despite its significant role in limiting digital initiatives’ effectiveness. Terms like “digital fairness” and “psychological empowerment” are well-established but often remain abstract, lacking concrete examples in existing HRM literature. Therefore, addressing this gap requires empirical studies exploring HRM practices’ effectiveness in enhancing digital skills (RQ3) and identifying barriers limiting the implementation of inclusive HR strategies (RQ4).

Based on this critical discussion, two main research questions arise:

RQ3: Which HRM practices are most effective in enhancing employees’ access to digital skills?

This question explores effective HRM strategies for increasing digital skill accessibility among employees.

RQ4: What barriers limit the implementation of inclusive HRM strategies for digital empowerment?

This question investigates organizational and cultural obstacles that hinder the successful implementation of digital HRM practices.

2.3. Digital Skills and Employee Performance

The shift from basic technical skills to genuine digital empowerment demonstrates the strategic importance of technology in the workplace. Digital empowerment goes beyond using tools; that means integrating them into problem-solving, innovation, and value creation. Achieving this level requires not only technical ability but also adaptability and confidence in using new technologies. In hybrid work settings, high performance comes from actively guiding and leveraging technology, not just using it passively (Cain & Coldwell-Neilson, 2024; Sneppen, 2025).

Digital skills influence several aspects of performance: task efficiency, adaptability, and support for others. Efficient digital tool use improves workflows and productivity, while digital empowerment accounts for a significant share of productivity differences among employees (Meena & Santhanalakshmi, 2025; Wehartaty & Ellitan, 2023).

Adaptive performance—handling technological changes—relies strongly on digital self-efficacy and confidence in experimenting with new systems. Autonomy and change-oriented self-efficacy further promote engagement and adaptability. Support performance, linked to collaboration and trust in digital environments, is enhanced when employees use emotional regulation strategies, fostering innovation and resilience (Katsaros, 2025; Schraub, 2011).

Beyond basic skills, digital adaptability and e-agency are now seen as key drivers of digital empowerment—the ability to control one’s digital environment with responsibility and confidence. However, structural barriers like unequal access to digital learning or organizational inertia often prevent skills from translating into actual performance. Without supportive HRM frameworks, digital empowerment remains theoretical and underused (Ciobanu et al., 2023; Passey et al., 2018).

Effective HRM strategies, such as mentoring, feedback, and HR analytics, help bridge the gap between knowledge and performance, while psychological empowerment and trust-building are essential to activate digital competencies in practice. Ultimately, digital empowerment is not guaranteed by skills alone, but depends on organizational culture, adaptive leadership, and ongoing support, ensuring that digital skills have a real impact at both individual and organizational levels (Barton & Barton, 2011; Tariq et al., 2025).

Moreover, digital skills should not be conceptualized as static abilities but as dynamic capabilities that evolve across different stages of employees’ professional development. The acquisition, application, and integration of digital competencies vary depending on the context, career phase, and digital maturity of both the individual and the organization (Cain & Coldwell-Neilson, 2024; Van Laar et al., 2017). For instance, onboarding phases may require foundational digital literacy, while more advanced roles rely on critical digital thinking, adaptation, and cross-functional collaboration. Understanding these developmental mechanisms is crucial for designing HRM strategies that align digital training with performance needs over time. As Mnyanyi and Ubwa (2024) point out, fostering digital influence rather than just literacy leads to sustainable performance growth, especially in environments characterized by continuous technological change (Mnyanyi & Ubwa, 2024).

Based on this analysis, two research questions are proposed:

RQ5: How do digital skills affect different types of employee performance (task, adaptive, support)?

This question explores the multifaceted impact of digital competencies on daily tasks, adaptability to change, and collaborative efficiency.

RQ6: What is the role of digital adaptability in job performance?

Here, the focus is on understanding how flexibility and digital empowerment enhance employee performance in dynamic technological environments.

2.4. Equality, Inclusion, and Organizational Development

Digital exclusion is a modern yet deeply rooted form of organizational inequality that affects employee participation, performance, and career advancement. Gaps in digital skills mirror broader socio-economic disparities, leading to structural exclusion at work. Lack of digital access acts as a subtle form of workplace marginalization. True digital inclusion requires not only access but also equal participation in decision-making and organizational processes. Effective HRM strategies must guarantee universal access to training and technology; otherwise, silent inequalities persist, and less digitally skilled employees remain sidelined. Organizational justice, through transparency and equal opportunities, is essential for inclusive and resilient workplaces (Priyamedha et al., 2025; Gnambs & Hawrot, 2025; Park, 2017).

Inclusion goes beyond physical presence; it requires fair access to information and opportunities in all justice dimensions—distributive, procedural, interpersonal, and informational. Digital disparities undermine fairness, create isolation, and reduce psychological empowerment, especially among vulnerable employees (Kim, 2025; Shore et al., 2018).

The digital divide can directly influence employees’ perceptions of organizational justice, particularly regarding fairness in access to information, training opportunities, and involvement in decision-making processes (Colquitt, 2001; Le et al., 2021). When certain groups of employees face barriers to digital tools or skill development, they may perceive organizational policies as inequitable or exclusionary. These perceptions of injustice can lead to lower organizational commitment, reduced engagement, and even resistance to technological changes (Colquitt et al., 2012; Shah et al., 2021). Moreover, perceived unfairness can negatively impact performance, collaboration, and willingness to participate in digital transformation initiatives. Thus, addressing the digital divide is critical not only for equality, but also for sustaining motivation and positive behaviors within the workplace.

HRM must actively promote digital equality through transparent communication, inclusive design, and monitoring exclusion indicators (Wu et al., 2025). Supporting employees with low digital confidence and addressing unconscious biases are key to fostering trust and engagement (Le et al., 2021; Shah et al., 2021). Leadership plays a crucial role in transforming workplace culture towards diversity and digital integration without exclusion (Muzumdar, 2025).

Assuming universal digital competence often leads to invisible exclusion, especially for vulnerable employees. Practices like digital mobbing exacerbate inequalities. Transformational leadership is essential to recognize and eliminate these silent barriers (Kim, 2025).

As highlighted, reducing digital inequalities requires strategic HRM interventions that combine justice, inclusion, and proactive leadership to turn technology into a tool for empowerment rather than division.

Based on the above, two research questions are formulated:

RQ7: How can HRM strategies reduce inequalities resulting from the digital divide?

This question examines how targeted HRM interventions can actively address hidden digital disparities, fostering equal opportunities for skill development, participation, and career advancement within organizations.

RQ8: How does digital exclusion affect perceptions of organizational justice and participation?

This question investigates the ways in which limited digital access shapes employees’ sense of fairness, inclusion, and their ability to engage fully in organizational decision-making processes.

2.5. Mapping the Research Questions: Conceptual Framework

The review of the literature shows that there is no integrated approach to how digital exclusion, HRM practices, employee performance, and organizational inclusion are connected in practice. Many studies focus separately on technology, human resources, or equality, but they do not explain how these elements interact inside workplaces. This lack of connection creates a gap, especially when it comes to designing effective strategies for digital empowerment and fairness at work.

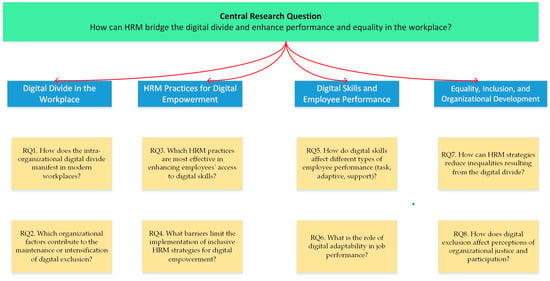

To organize these complex topics, a conceptual framework was developed. This framework links the central research question—how HRM can bridge the digital divide and improve performance and equality—with eight specific research questions. Each set of questions reflects a key area discussed in the literature: digital divide, HRM practices, digital skills, and inclusion.

As shown in Figure 1, the framework presents how these four pillars are related to the research focus. It helps to clarify the direction of the study and supports the transition from theory to empirical investigation.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework of Research Questions.

This structure will serve as the foundation for the methodological approach, ensuring that the study responds not only to theoretical gaps but also to practical challenges faced by modern organizations.

3. Methodology

The research included in the current study was conducted from June 2024 until February 2025. The research was quantitative, using an online questionnaire. The questionnaire was given to employees through the SurveyMonkey platform www.surveymonkey.com (accessed on 20 February 2025) via a special hyperlink that was sent to their companies. The companies’ data were taken by the Commercial Chambers of Greece and from the Offices of Economic and Commercial Affairs located in the Greek embassies in European capitals. The businesses to which the emails were sent had at some point in the past or even currently, cooperation with Greek companies for commercial or other purposes, and this is why they were indexed in the above lists. Also, the email explained the full purpose of the research and asked the Human Resources departments of each company to forward it to the employees for completion.

The research fully ensured the anonymity of participants. In no case is the profiling of respondents conducted, nor is there a connection with their particular characteristics. Also, in no case were the answers linked with the company name where they are working, while it was ensured that IP addresses were not recorded in order to avoid any possible future connection, since the data are open and accessible to everyone via FigShare www.figshare.com (accessed on 18 April 2025). Finally, in every case, the EU Regulation 2016/719 and Directive 95/46/EC regarding the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) were respected, as it was adopted, legislated, and applied in each EU country (European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training, 2023).

In terms of data handling and protection, all responses were collected anonymously via the SurveyMonkey platform and exported to a secure, password-protected environment accessible only to the research team. No personal identifiers (such as names, email addresses, or company names) were collected or stored at any stage. Data files were regularly backed up on encrypted drives to prevent unauthorized access or data loss. Only aggregated, de-identified data were used for statistical analysis and reporting, ensuring that no individual respondent could be identified. After the completion of the analysis, the anonymized dataset was deposited in the public Figshare repository, in line with open science principles. All procedures strictly complied with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and best practices for research data management (European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training, 2023).

The data collection was conducted in four consecutive phases through electronic distribution of the questionnaire to a total of 12,512 companies operating in the EU. The initial distribution (June 2024) to 7500 companies led to the gathering of 322 fully completed questionnaires. After a second distribution (July) and without additional reminders in August, the total number gradually increased to 582. Reminders in September and October contributed to the collection of 780 responses, while a new distribution to 2512 companies during November-December resulted in the final collection of 1023 fully completed questionnaires by 31 December 2024. This strategy highlighted the value of a repetitive approach and the expansion of the sending field for ensuring a representative sample.

The questionnaire was addressed to employees characterized as white collar, meaning administrative tasks and not manual labor. Also, it was not addressed to HR managers or executives directly involved in the strategic planning of Human Resources policies. The research focused exclusively on white collar employees, including those holding managerial positions, as long as they did not belong to the HR department or related executive structures. Practically, we addressed this audience because the questionnaire aimed to study subjective experiences, perceptions, and the perceived reality, and in no case did it target those who are experts in the strategic design of Human Resources policies of each company (Degryse, 2016; OECD, 2019).

Although blue-collar (manual) workers are increasingly required to engage with digital technologies, such as IoT devices, automated machinery, and digital platforms, the present analysis is limited to white-collar employees. This focus is due to both methodological and conceptual reasons. The questionnaire and research design are oriented towards environments where HRM policies are formally structured and implemented, which most frequently apply to administrative, managerial, and knowledge-based positions. Recent literature highlights that digital inequality among blue-collar workers is a significant, yet underexplored issue, shaped by sector-specific and socioeconomic factors. It is acknowledged that digital exclusion in manual occupations may present distinct characteristics and challenges. Future research is encouraged to develop tailored tools and approaches to examine digital empowerment and the impact of automation among blue-collar employees, in order to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the digital divide in the workforce.

As it is concluded, the sample for the research followed a strategy of sampling, since neither specific companies nor employees were directly selected. Instead, we addressed an extremely wide range of companies in terms of economic activity and geographical scope. The sample had purposive elements because, although there was no full randomization, there was a clear targeting of white-collar employees, non-HR department staff, and companies operating within the EU. It is a fact that we tried and achieved broad geographical coverage, satisfactory response with a high level of completeness, and easy access to a specific population of employees. Finally, it is important to highlight that the results allow analytical generalization, given the large number of participants (N = 1023), the diversification of the sample, and the targeted selection of the population.

Furthermore, the sample was designed to include a wide variety of companies across different economic sectors, geographical locations, and organizational sizes, ranging from SMEs to large multinationals. This variety aimed at capturing diverse employee experiences with digital transformation in order to improve the external validity of the findings. Special attention was paid to balance gender, age, and job role distribution across the sample to reflect the heterogeneity of the modern workforce, in line with recommendations on sampling quality and questionnaire design (Boynton & Greenhalgh, 2004).

To strengthen the representativeness and diversity of the sample, the research design targeted a broad range of organizations operating across multiple industries and varying in size. The distribution lists used for contacting companies were compiled from official sources—such as Commercial Chambers and Offices of Economic and Commercial Affairs—encompassing organizations active in sectors including services, manufacturing, trade, and technology, among others. No restrictions were imposed regarding organizational size; both small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and larger corporations were included in the outreach. While the sampling was not fully random, the large number of participating companies (N = 12,512 approached, N = 1023 respondents) and the purposive effort to cover different sectors and company scales contribute to the diversity of the sample. This approach supports analytical generalization and offers insights that reflect a wide spectrum of workplace contexts within the European Union (Boynton & Greenhalgh, 2004).

The sample for this study was obtained through purposive sampling via company outreach, targeting employees in both public and private vocational training institutions within Greece. While this approach allowed for focused data collection from relevant sectors, it limits the generalizability of the findings. The sample may not fully represent all sectors, regions, or countries within the EU. Consequently, caution is advised when extending conclusions beyond the sampled population. Future research should aim to include a more diverse and representative sample across various industries and EU countries to validate and expand upon these findings.

The selection of companies was based on their commercial or other activities in EU countries. We chose these companies because the EU represents a reference framework for the policies applied in Europe, the general perception of companies regarding digital inclusion and the financial subsidies they receive for this purpose from the EU, and finally for the equal opportunities they offer, generally speaking, compared to other geographical areas of the world. Additionally, companies were selected geographically because there is homogeneity regarding GDPR, as they share common regulatory and cultural parameters. Practical criteria, such as the official lists provided by the Offices of Economic and Commercial Affairs through the Greek embassies, were also considered.

The questionnaire that respondents were asked to complete was based on two axes. The first axis included 5 demographic questions, while the second axis was the main part, consisting of 4 categories with 7 questions each (Table 1 & Appendix A). With a total of 33 questions, its completion required approximately 22 to 27 min. All questions were closed-ended, while the questions in the specific axis were in a 5-point Likert scale format. The five-point Likert scale was selected due to its advantages in quantitative analysis and mainly for facilitating the analysis through the PLS-SEM method used, since variables can be considered continuous. Also, the easy understanding and quick completion of questions in this scale were other important factors for selecting this method (Boynton & Greenhalgh, 2004). All items in Section 1 (Digital Divide) are negatively worded, so that higher scores indicate greater perceived digital exclusion. No reverse coding was applied; thus, higher mean values in this construct correspond to a greater sense of digital exclusion among respondents. In Section 4, item 23 is positively worded to reflect the absence of exclusion (higher scores indicate less perceived exclusion). All analyses and interpretations in this manuscript are consistent with this coding direction. Finally, it is worth mentioning that all questions were formulated in the English language.

Table 1.

Questionnaire Items by Category.

Before being distributed for completion, the questionnaire was given for pilot testing. Initially, in the first phase of the pilot testing, which lasted 10 days, colleagues and experts participated. In the second phase, which lasted 21 days, random employees who knew English and worked in companies from EU countries participated. During the two phases, the clarity of the wording of the questions, the completion time of the questionnaire, and the logical flow of answers were checked, and minor linguistic corrections were made.

To ensure both validity and reliability, the questionnaire items were developed based on established constructs and adapted from widely used, validated instruments in the fields of HRM, digital skills, and organizational inclusion. Face validity was assessed by a panel of subject-matter experts and experienced researchers during the first phase of pilot testing, who reviewed each question for clarity, relevance, and alignment with the study’s objectives. Construct validity and internal consistency were further evaluated through statistical methods (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha, Composite Reliability, AVE), with all key indices meeting recommended thresholds. During the second phase of pre-testing with target respondents, cognitive interviews and feedback were used to identify and resolve any ambiguities, cultural biases, or technical language that could impact data quality. Adjustments were made to the wording and order of several questions to optimize comprehension and logical flow. This iterative process helped to refine the questionnaire, minimize measurement error, and ensure the quality and interpretability of the collected data (Hair et al., 2022).

After completing the questionnaire, validity and reliability tests were conducted through the software used for the statistical analysis. The software was Smart PLS (version 4.1.1.2), and for some combined results of the demographic questions, Jamovi (version 2.6.26) was used. Initially, the internal consistency of the four categories of the specific part was examined through Cronbach’s Alpha, Composite Reliability (rho_a and rho_c), and Average Variance Extracted indicators (Hair et al., 2022).

The Cronbach’s alpha indicator reflects the internal consistency of the questions of each thematic section. The Composite Reliability rho_a is considered more accurate for PLS-SEM, as it is based on the correlations between variables, while the Composite Reliability rho_c evaluates reliability based on indicator loadings and is used as the main composite reliability indicator in this context. In any case, the use of both indicators was considered necessary since the statistical analysis that follows in the next chapter requires consistency in both indicators, as rho_a is more sensitive to internal inconsistencies, while rho_c provides a more conservative estimation of composite reliability. Finally, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) indicator reflects the percentage of variance explained by each latent construct and is used for evaluating convergent validity (Hair et al., 2022).

All four axes showed excellent internal consistency and reliability (Table 2), with Cronbach’s alpha values from 0.983 to 0.990 and Composite Reliability rho_c values from 0.985 to 0.992. The Composite Reliability rho_a values were also high (0.857 to 0.990), confirming the stability of the results. Similarly, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) indicator exceeded the threshold of 0.50 in all variables, which confirms the adequacy of convergent validity. Overall, the indicators demonstrate that the measurement tools used in the questionnaire have high reliability and are suitable for modeling the variables in this research (Hair et al., 2022).

Table 2.

Reliability and Validity Metrics.

The discriminant validity of the four categories of the present study (Table 3) was evaluated using the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) indicator, as suggested by modern literature in the PLS-SEM approach. The HTMT indicator is considered more reliable compared to traditional methods, as it focuses on the relationships between questions of different variables and directly evaluates their conceptual distinction. In this research, the HTMT values remained below the defined threshold of 0.85, which is considered acceptable for ensuring discriminant validity (Henseler et al., 2015). Keeping the values within this limit demonstrates that each thematic category measures a different and clearly defined dimension, allowing a reliable interpretation of the correlations between the variables of the model.

Table 3.

Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio.

Beyond the HTMT indicator, the discriminant validity of the thematic variables was also evaluated through the Fornell–Larcker criterion (Table 4). According to this criterion, the square root of the AVE of each variable should be greater than its correlations with any other variable in the model (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). In the present analysis, this condition is fully satisfied for all thematic categories. The fulfillment of this criterion confirms the conceptual distinctiveness of the constructs and provides additional validity to the modeling of the relationships in the model.

Table 4.

Fornell-Lacker criterion.

In the context of evaluating the structural model, a multicollinearity check was performed using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) indicator (Table 5). All VIF values for the relationships between variables were below the acceptable threshold of 3.3, which is suggested in the literature for the PLS-SEM approach (Diamantopoulos & Siguaw, 2006). This result confirms that there are no multicollinearity phenomena that could distort the estimation of the model paths. Also, it is worth noting that, as shown in Table 5, the variable HRM_PRACTICES operates as a dependent variable but is not used as an independent one for predicting other variables. Therefore, no VIF value is presented in its column. The same applies to the variable INCLUSION, which does not participate as a dependent variable in the structural model, and for this reason, a corresponding row is missing.

Table 5.

Variance Inflation Factor (VIF).

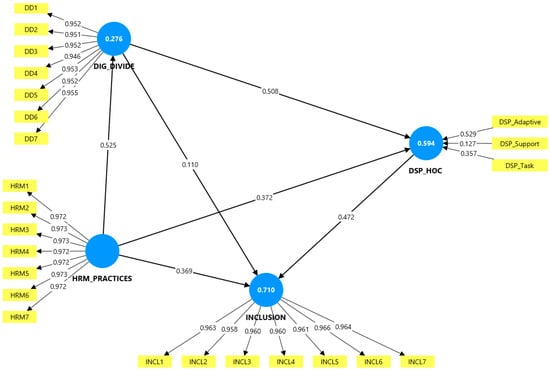

After confirming the discriminant validity and checking for multicollinearity, the analysis proceeds to the exploration of relationships among the main constructs through structural equation modeling (SEM). The SEM framework was designed to capture the complex interactions between human resource management practices, digital skills, inclusion, and the digital divide.

In this case, the single conceptual construct is DSP, and in order to enhance theoretical clarity, simplify the structural model, and improve the predictive ability of the relationships, three sub-dimensions were created: DSP_Task, DSP_Adaptive, and DSP_Support.

- DSP_Task: Use of tools and completion of digital tasks (Q3.1, Q3.2, Q3.3)

- DSP_Adaptive: Adaptability to new technologies and innovation (Q3.4, Q3.5, Q3.6)

- DSP_Support: Supporting colleagues and trust in digital processes (Q3.7)

As a result of these, the latent variables are created as follows (Table 6):

Table 6.

Latent Variables and Corresponding Questionnaire Items.

The selection of the four conceptual axes (DIG_DIVIDE, HRM_PRACTICES, DSP, INCLUSION) reflects the theoretical intention of the model to highlight how human resources practices and individual digital capabilities affect the experience of equality in a digitally transforming work environment. Also, the HOC model that was adopted follows the logic of reflective-formative type, as the first three-level dimensions (DSP_Task, DSP_Adaptive, DSP_Support) are considered to form the overall DSP construct. This approach is consistent with theoretical models that represent complex concepts as consisting of distinct, complementary dimensions (Becker et al., 2012).

Demographic variables (age, gender, educational level, and years of experience) were not included as control variables in the primary SEM analysis. This decision aimed to maintain focus on the model’s core theoretical constructs and avoid overfitting. The potential influence of demographic factors is acknowledged as a limitation, and their inclusion is recommended for future research.

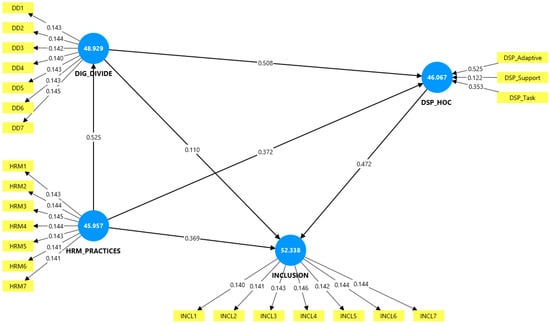

Figure 2 presents the structural model used in the PLS-SEM analysis, showing the latent constructs and their interrelations.

Figure 2.

Structural Model (PLS-SEM).

Although this study relied on a single quantitative method (PLS-SEM), future research could benefit from methodological triangulation. Combining survey data with qualitative techniques, such as interviews or case studies, would offer richer insight into the living experiences of employees and the nuanced impact of HRM practices on digital inclusion. Additionally, incorporating secondary data or observational methods could strengthen the robustness and depth of analysis, as suggested by Boynton and Greenhalgh (2004) in the context of mixed-methods research design (Boynton & Greenhalgh, 2004).

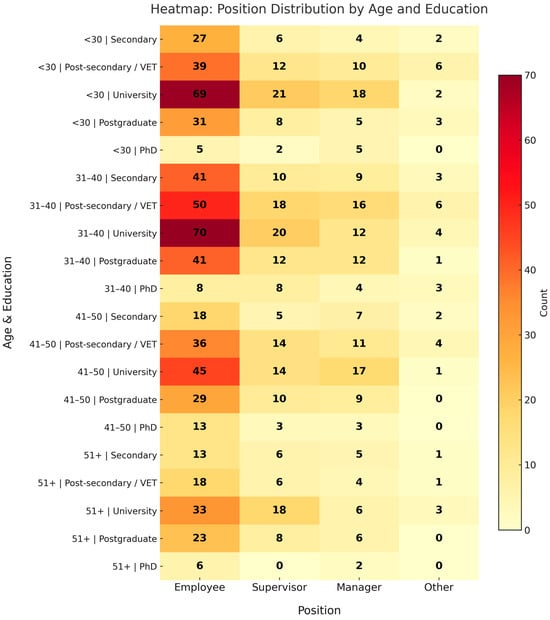

4. Results

The demographic results of the research present particular interest. Since the research was conducted on 1023 respondents, two combined Heatmap-type charts were selected to present the demographics, integrating all the information of the study. Initially, in Figure 3, the visualization of age, educational level, and the position of respondents in the company was chosen. These variables were used because we can observe to what extent the access to career advancement opportunities of human resources is directly affected. Age, as well as the level of education, is often related to digital skills and adaptability to new tools. The variable of job position within a company is an element of the structural rise of the respondent in the decision-making process.

Figure 3.

Heatmap of Positions Across Age and Education Levels.

Through the perusal of Figure 3, it is observed that the most populated categories are individuals under 40 years old with university or postgraduate education, mainly working as employees. Managerial positions are less frequent and are occupied by individuals over 40 years old. Finally, PhD holders are very few and are distributed in roles either as employees or managers, but without a significant presence in supervisory positions. In this context, it should be considered that the connection of these three variables reflects the concept of organizational mobility, which is influenced by access to education and familiarity with new technologies. As Ragnedda et al. mention, social and digital inequalities intersect, affecting both career advancement opportunities and the perception of equality within organizations (Ragnedda et al., 2022).

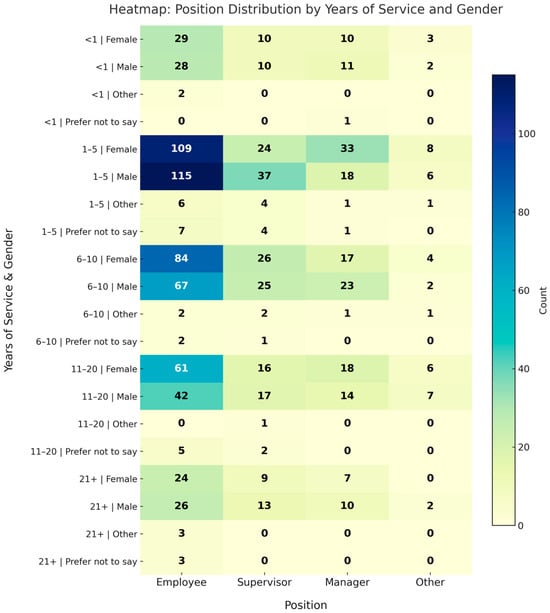

The second heatmap (Figure 4) illustrates the relationship between years of service, gender, and job position. The analysis confirms that professional experience is positively associated with taking responsibility positions, while gender still influences the position within the organization. Men with 6+ years of experience appear more frequently in managerial roles, while women remain mainly in employee roles. This differentiation confirms the existence of gender barriers in organizational mobility, especially at older ages. This finding is aligned with the literature regarding gendered leadership trajectories in organizational environments (Eagly & Karau, 2002). Last but not least, the Heatmap charts were created using Python software (version 3.10), utilizing the pandas (1.5.3) and seaborn (0.12.2) libraries for data processing and their visualization.

Figure 4.

Heatmap of Position, Experience, and Gender.

Following the demographic analysis, the results section turns to the interpretation of the main statistical findings from the SEM model. The analysis of the path coefficients reveals the dynamics of the relationships between the main latent variables of the model. The variable HRM_PRACTICES shows a strong positive effect on DIG_DIVIDE (β = 0.525), indicating that the existence of human resources empowerment strategies is related to the reduction of digital inequalities in the workplace. At the same time, HRM_PRACTICES positively affects both INCLUSION (β = 0.369) and DSP_HOC (β = 0.372), suggesting that HR policies lead, on the one hand, to a greater sense of equality and, on the other hand, to improved digital performance. The variable DIG_DIVIDE is also strongly connected with DSP_HOC (β = 0.508), reinforcing the view that the digital gap is a critical factor in shaping digital performance. The effect of DIG_DIVIDE on INCLUSION is smaller but positive (β = 0.110). Finally, INCLUSION significantly affects DSP_HOC (β = 0.472), confirming the importance of an inclusive environment in fostering digital skills.

The interpretation of the R2 values in the model provides indications about the percentage of variance of the dependent variables explained by the respective independent variables. Specifically, INCLUSION shows a very high R2 value = 0.710, meaning that 71% of the variance in the perception of equality is explained by the variables HRM_PRACTICES and DIG_DIVIDE, supporting the view that both organizational support and the digital background of employees influence the sense of equality in the workplace. Similarly, DSP_HOC, which gathers the three sub-dimensions of digital skills and performance, is explained by 59.4% (R2 = 0.594) from the variables HRM_PRACTICES, DIG_DIVIDE, and INCLUSION, showing a very satisfactory predictive ability. Finally, the variable DIG_DIVIDE has an R2 value = 0.276, which highlights the relative influence of external factors on the experience of digital exclusion, without being a central dependent variable of the model.

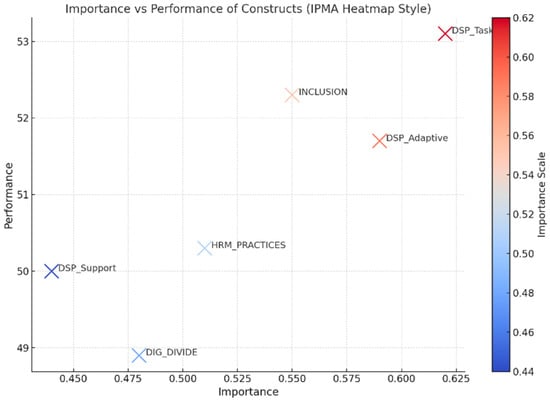

Figure 5 presents the IPMA results, highlighting the relative performance and importance of each latent variable in predicting DSP_HOC.

Figure 5.

IPMA of Structural Model Constructs.

As shown by the IPMA Scatterplot (Figure 6), the variable INCLUSION presents the highest performance (52.3) compared to the other latent variables, indicating that participants perceive the existence of relative equality in the workplace. However, the variable DIG_DIVIDE, while showing lower performance (48.9), presents a high degree of importance, highlighting the potential influence of the digital divide in enhancing digital performance. Similarly, the sub-dimensions DSP_Task and DSP_Adaptive record higher importance compared to the sub-dimension DSP_Support, revealing that usage practices and adaptability to technologies play a stronger role in strengthening the digital profile of employees. Therefore, IPMA reveals critical intervention areas and indicates that organizations should focus more on reducing the digital divide and enhancing employees’ adaptability in order to improve their digital effectiveness.

Figure 6.

IPMA Scatterplot for Latent Variables.

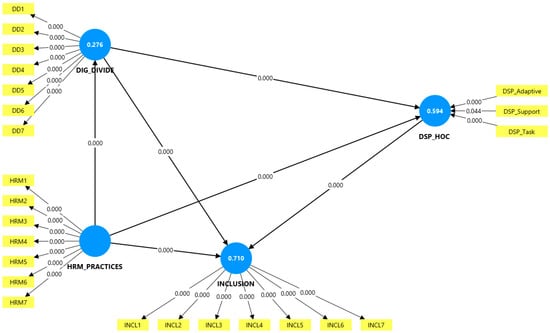

In the final analysis of the present research (Figure 7), the mediation technique was applied in order to investigate whether the variable INCLUSION acts as an intermediary link between HRM_PRACTICES and DSP_HOC. Mediation refers to situations where the effect of an independent variable on a dependent variable is not direct but passes through a third variable (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Based on Figure 7 and Table 7 presented, it is observed that HRM_PRACTICES positively affects INCLUSION with a coefficient value β = 0.359, strongly statistically significant (p < 0.001, t = 22.585). Also, INCLUSION affects DSP_HOC with a value β = 0.472 (p < 0.001, t = 18.362), while finally HRM_PRACTICES also directly affects DSP_HOC with β = 0.267 (p < 0.001, t = 16.511).

Figure 7.

Mediation Paths Significance in Structural Model.

Table 7.

Mediation Analysis—Path Coefficients and Significance.

Beyond the basic mediation effects, additional paths were analyzed to better understand complex relationships within the model. The extended mediation analysis presented in Table 8 shows how different indirect paths are connecting HRM practices, digital divide, inclusion, and digital performance. It is clear that HRM_PRACTICES influence DSP_HOC not only directly but also through DIG_DIVIDE and INCLUSION in different combinations. Especially, the path HRM_PRACTICES → DIG_DIVIDE → DSP_HOC → INCLUSION demonstrates a strong indirect effect, which explains how reducing digital inequalities can improve inclusion and finally the digital performance of employees. Also, the path DIG_DIVIDE → DSP_HOC → INCLUSION confirms that digital exclusion is playing a critical role in limiting organizational inclusion if it is not managed properly. These results support the idea that HRM strategies must focus not only on skills development but also on creating fair digital environments where all employees can participate without barriers. The mediation effects highlight that inclusion is not happening automatically, but it needs structured interventions to reduce the negative impact of the digital divide inside workplaces.

Table 8.

Extended Mediation Analysis.

The existence of both direct and indirect effects through INCLUSION confirms the presence of partial mediation. Therefore, Human Resources policies not only directly influence digital performance, but also through strengthening the sense of inclusion and equality of employees, which emerges as a critical mechanism for enhancing digital skills.

The existence of both direct and indirect effects through the variable INCLUSION confirms the presence of partial mediation. Therefore, Human Resources policies not only directly affect employees’ digital performance (DSP_HOC) but also indirectly, through reinforcing the sense of inclusion and equality in the workplace environment. The variable INCLUSION emerges as a critical mechanism, as it enhances psychological safety and encourages employees to utilize their digital skills.

Importantly, the results demonstrate that HRM strategies exert not only direct but also significant indirect effects on employee inclusion, mediated through enhancements in digital skills and the reduction of digital inequalities. This finding underscores the theoretical proposition that HRM policies can be a powerful lever for organizational justice and digital empowerment, extending their influence beyond immediate workforce management to broader inclusion outcomes (Bondarouk & Brewster, 2016; Le et al., 2021). Moreover, the analysis reveals that the digital divide manifests differently across employee groups—particularly with respect to age, education level, and job function—with older employees and those in operational roles experiencing greater barriers to digital participation. These insights contribute to existing theory by clarifying the multiple pathways through which HRM interventions shape both digital and social inclusion within evolving workplaces.

Finally, further analysis shows that not all digital skills contribute equally to employee performance. For example, advanced analytical and problem-solving skills are particularly associated with higher levels of task performance and innovation, especially in managerial and technical roles. In contrast, basic digital literacy, such as proficiency with office software or online communication tools, mainly supports routine efficiency and day-to-day collaboration (Van Laar et al., 2017). The results also indicate the impact of digital skills on performance varies across organizational settings: In larger organizations and technology-driven sectors, the demand for advanced digital competencies is greater, resulting in larger performance gaps between employees with high and low digital skill levels. Conversely, in smaller firms or less digitalized environments, foundational digital skills play a more prominent role in supporting overall job performance. These distinctions highlight the need for tailored digital upskilling initiatives that address the specific performance requirements of diverse organizational contexts.

5. Discussion

The following discussion interprets the results in light of the conceptual framework and each of the research questions posed.

The analysis of the results (Table 9) regarding the first research question (RQ1) showed that the digital divide manifests in different ways within the organization. In many cases, it appears as a feeling of limited access to digital tools or as the perception that some employees lack digital skills compared to others. The variable DIG_DIVIDE, which included questions like “I have fewer skills than my colleagues” or “I feel insecure in front of technology”, showed statistically significant correlations with other key variables, such as DSP_HOC and INCLUSION. This indicates that the digital divide is not just a situation of lacking skills but is also connected with how employees feel integrated into the organization and how they perceive their personal performance. Furthermore, from the IPMA map, it is observed that although the performance of DIG_DIVIDE was relatively low, its importance for enhancing digital performance was high. Practically, the digital divide should not be underestimated, as it represents a key obstacle for the active participation of employees in the digital environment of the organization. This empirical finding is consistent with the literature, which supports that the digital divide manifests within organizations in ways that are often invisible or underestimated (Van Deursen & Helsper, 2015). Employees who feel “behind” technologically are often marginalized from developments, which affects their participation in new initiatives or their sense of professional value.

Table 9.

RQ Validation through SEM Analysis.

Regarding RQ2, organizational factors related to digital exclusion are mainly identified in how human resources practices (HRM_PRACTICES) are applied. From the path coefficients analysis, it arises that HRM practices positively affect DIG_DIVIDE with a value β = 0.525. Although this correlation seems contradictory, in reality, it reveals that the lack or unequal application of HR practices may enhance the feeling of digital exclusion, especially when equal access to training or support opportunities is not provided. This is also supported by the IPMA indicator, which shows the high importance of DIG_DIVIDE in predicting digital performance. At the same time, from the variable HRM_PRACTICES, which includes questions, such as participation in training or the existence of encouraging practices, it appears that when a coherent strategy is missing, internal inequalities are created. The literature emphasizes that organizational factors, such as learning culture, equality in access to technological resources, and leadership support, influence the existence or reinforcement of the digital divide (Ragnedda et al., 2022). This positive path coefficient suggests that, in environments with more advanced HRM practices and digital initiatives, employees may become more aware of digital exclusion and disparities. As HRM invests in digital upskilling and tools, previously hidden gaps or new forms of exclusion are revealed—particularly among employees less adaptable to rapid technological change. Therefore, the positive relationship likely reflects not an increase in exclusion caused by HRM, but rather the increased visibility and recognition of the existing digital divide in more digitally mature organizations (Van Deursen & Helsper, 2015). Therefore, the findings confirm that the digital divide is not only a result of individual characteristics but also of organizational choices. Consequently, organizations advancing in digital HRM need to monitor not only technological provision but also equity in access and support, so as to prevent the surfacing of new or hidden digital divides.

Regarding RQ3, the impact of HRM practices on employees’ digital performance is clearly reflected in the model, with a significant positive correlation between HRM_PRACTICES → DSP_HOC (β = 0.372). This means that when organizations implement practices such as training, support for new tools, and equal access, employees develop their digital skills more dynamically. This importance is also confirmed by the IPMA results, where HRM_PRACTICES show high importance and medium performance, indicating room for improvement. Practically, efforts are being made, but there is potential for these practices to be used more effectively. Finally, empirical literature agrees: human resources practices are a key tool for enhancing digital capabilities, especially when they combine technical training with a culture of continuous learning (Bondarouk & Brewster, 2016).

The fourth research question investigates the barriers that may limit the implementation of inclusive human resources strategies for enhancing digital empowerment. From the data analysis, it is observed that although HRM_PRACTICES are positively related both to the enhancement of digital skills (β = 0.267) and to the enhancement of equality (β = 0.359), the performance level of participants in these practices is not particularly high, with values below 50 in the IPMA map. This indicates that HR strategies are applied unevenly or are limited in practice. Moreover, the moderate performance of the variable DSP_Support, which is related to trust and colleague assistance, suggests that even when training infrastructures exist, a climate of collaboration and encouragement is missing. This may be due to institutional barriers, such as a lack of inclusion culture, or practical obstacles, like insufficient access to quality training. According to the literature, the successful implementation of inclusive HRM strategies requires not only planning but also internal commitment from management and line managers (Farndale et al., 2010). Therefore, although HRM strategies are an important tool for digital empowerment, the barriers are mainly found at the stage of their implementation, partially confirming the research question.

The fourth research question also examines whether Human Resources strategies (HRM_PRACTICES) are applied in a way that equally enhances employees’ digital empowerment. From the SEM analysis, it emerges that HRM_PRACTICES have a strong positive effect on INCLUSION (β = 0.359) and DSP_HOC (β = 0.267), while the IPMA reveals that although the importance of HRM_PRACTICES for digital performance is high, the performance (49.6) is lower. This means that, although HRM strategies are theoretically effective, in practice, they may be applied in a fragmented way or with deviations. The lower performance value of DSP_Support (44.4) is related to colleague support and trust in the workplace environment. It also indicates the absence of an inclusion culture that would reinforce HRM practices. This is supported by literature, where it is emphasized that the success of HRM strategies depends not only on design but also on commitment and the prevailing workplace climate. Therefore, based on the high path coefficient values and confirmation through the IPMA map, the question is confirmed, as the barriers do not concern whether the strategies are effective, but rather whether they are properly implemented (Farndale et al., 2010).

The fifth research question examines if and how individual digital skills are related to different aspects of performance. In the present research, performance is divided into three dimensions: DSP_Task (ability to complete tasks using digital tools), DSP_Adaptive (adaptation to new digital environments), and DSP_Support (supporting colleagues and trust in digital processes). All these are included in the higher-order variable DSP_HOC. The statistical analysis with PLS-SEM shows that the factors HRM_PRACTICES, DIG_DIVIDE, and INCLUSION strongly affect DSP_HOC, with β = 0.372, β = 0.508, and β = 0.472, respectively. From a theoretical perspective, the findings confirm previous studies linking digital skills with adaptive performance and proactive behavior in the workplace. As mentioned in the literature, adaptive performance is a critical element for employees’ survival in constantly changing digital environments, while task performance remains fundamental for daily operations (Parker & Collins, 2010; Pulakos et al., 2000). Therefore, RQ5 is fully confirmed, as the different aspects of digital skills are related to distinct but interconnected forms of performance, both based on the data of the present study and on theoretical approaches.

Regarding RQ6, digital adaptability, as measured through the sub-construct DSP_Adaptive (Q3.4–Q3.6), emerges as a critical element of the overall variable DSP_HOC. Its importance is confirmed both by the high weight in the HOC and by the IPMA, where it shows significant importance for enhancing digital performance. This result is consistent with the literature, which states that the ability to adapt to technological changes is a key factor in maintaining performance (Heijde & Van Der Heijden, 2006).

Regarding RQ7, we observe that this is also confirmed. The variable HRM_PRACTICES has a strong impact both on DIG_DIVIDE (β = 0.525) and on INCLUSION (β = 0.359), indicating that organizational strategies for employee empowerment are linked to reducing digital inequalities and fostering an environment of equality. Therefore, HRM policies are not only a lever for training but also a tool for combating structural exclusions caused by the digital divide (Bondarouk & Brewster, 2016).

Finally, RQ8 is mainly explored through the relationship between the variable DIG_DIVIDE and INCLUSION. Although the effect is positive (β = 0.240) and statistically significant (p < 0.001), it remains weaker compared to other relationships in the model. This means that respondents experiencing digital exclusion tend to feel a reduced sense of inclusion in the organization, but this effect is not entirely decisive. The partial confirmation of RQ8 is based on the fact that the digital divide does influence perceptions of inclusion, but not to a degree that fully explains the phenomenon. Possibly, organizational culture, personal resilience, or other social factors act as counterbalances, as suggested by Colquitt et al. (2013) in the field of organizational justice. Therefore, the question is partially confirmed: digital exclusion does affect perceptions of equality and participation, but the relationship is more complex than what is captured solely through DIG_DIVIDE (Colquitt, 2001).

In a more systematic way, this study provides clear theoretical contributions that advance the understanding of digital inequalities, organizational justice, and Human Resource Management (HRM) practices in contemporary workplaces. First, it enriches digital divide theory by empirically illustrating how organizational factors, particularly structured HRM interventions such as targeted training programs and equitable resource allocation, can mitigate internal digital inequalities (Ragnedda et al., 2022; Van Deursen & Helsper, 2015). Unlike traditional approaches that emphasize primarily technical infrastructure, this study highlights that addressing digital exclusion also requires strategic organizational choices aimed at fostering an inclusive digital culture.

Second, the research significantly advances organizational fairness theory by elucidating the intricate ways digital inequalities affect employees’ perceptions of fairness, inclusion, and organizational trust. By explicitly demonstrating that employees experiencing digital exclusion perceive lower levels of organizational justice, the findings clarify how digital divides are deeply intertwined with employees’ psychological experiences and behavioral outcomes, such as reduced engagement and participation (Colquitt et al., 2013; Le et al., 2021). Thus, digital fairness emerges as a critical, yet previously underexplored, component of overall organizational fairness frameworks.

Lastly, the study makes substantial contributions to HRM theory by providing robust empirical evidence on the mediating role of inclusive HR practices in enhancing digital skills and organizational inclusion. It confirms and extends previous research by demonstrating that HR interventions focused on digital training, equal resource access, and supportive organizational climates are essential for achieving both individual digital empowerment and broader organizational effectiveness (Bondarouk & Brewster, 2016; Farndale et al., 2010). Additionally, mediation analysis strengthens theoretical arguments around HRM, highlighting the strategic significance of creating inclusive environments as pathways to improved digital performance and reduced inequalities.

Overall, these contributions offer a more nuanced theoretical understanding of how the digital divide, organizational fairness, and strategic HRM interact, providing scholars and practitioners with clearer directions for future research and organizational policy development in digitally evolving workplaces.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

The theoretical examination of the digital divide in the workplace highlights this multidimensional impact, affecting not only productivity but also social equality and organizational justice (Szabó, 2024). The digital divide reflects the unequal access and usage of technology, leading to differences in skills, knowledge, and opportunities between employees (Sang, 2024), influenced by factors like geography, education, and age (Grzenkowicz, 2025).

Khort et al. (2024) argue that this divide creates forms of epistemic injustice, where some groups have limited access to important knowledge (Khort et al., 2024). This study supports that view, showing how digital exclusion can silently limit equal participation and reinforce hidden inequalities inside daily organizational life. Connecting this phenomenon with the organizational justice theories explains how digital gaps increase perceptions of unfairness and reduce inclusion (Le et al., 2021; Muzumdar, 2025). Furthermore, our findings suggest that digital inequalities not only impact fairness but also weaken employee engagement and trust in digital environments.

The digital divide also reduces the effectiveness of professional development programs, leaving many employees unprepared for the advanced digital tasks, which restricts career growth and deepens existing disparities (Ragnedda et al., 2022). This research highlights that without targeted HRM interventions, such skill gaps risk becoming permanent structural barriers.

In addition, exclusion from digital collaboration and communication processes may act as a silent form of workplace marginalization(Špadina & Ljubić, 2024). This situation, together with reduced psychological empowerment, can negatively influence job security feelings (Schraub, 2011). Our analysis emphasizes that digital exclusion is not just technical but is deeply connected to employee well-being and organizational cohesion.

Digital leadership is a key factor for addressing these challenges. More than technical guidance, effective leadership should promote a culture where digital inclusion and continuous learning are the core of organizational values (Priyamedha et al., 2025; Aggarwal & Stanley, 2025). This study underlines that fostering such a culture helps technology to be transformed from a source of division into a tool for empowerment.

In conclusion, addressing the digital divide requires systematic HRM strategies that integrate reskilling, fair access to digital resources, and policies supporting inclusion (Szabó, 2024; Wehartaty & Ellitan, 2023). These theoretical insights are contributing to expanding existing frameworks by showing how digital inequalities intersect with organizational justice, professional development, and employee participation in modern workplaces.

5.2. Practical Implications

Addressing the digital divide in workplaces has important practical consequences for Human Resource Management (HRM) and organizational performance. While digital tools can improve efficiency and innovation, they often increase inequalities in access and usage (Szabó, 2024). This leads to reduced productivity, unequal skill distribution, and limited employee participation in digital environments, as also reflected in our IPMA analysis, where key variables showed high importance but moderate performance.

One major implication is the need for continuous upskilling and reskilling strategies. Organizations that avoid investing in digital skills development risk losing flexibility and competitiveness (Jawwad, 2023). Our findings confirm that HRM practices have a strong impact on reducing digital exclusion and improving inclusion, especially through targeted training programs and supportive environments. For example, implementing mentoring systems or personalized digital learning paths can help employees adapt better during digital transitions.

Moreover, digital exclusion can act as a silent barrier, limiting collaboration and participation. This was highlighted both in the literature and in our mediation analysis, where inclusion played a key role between HRM strategies and digital performance (Špadina & Ljubić, 2024). Therefore, organizations should establish clear policies against digital isolation, promoting open communication and equal access to digital resources.