1. Introduction

Conflict is unavoidable in any structure. It could arise as a difference in goals or values and even in interpersonal aspects (

Madalina, 2016). However, effective leadership and mediation could serve as tools for conflict prevention.

The aim of public organization is to provide services to the society. Therefore, in order to provide quality services, it is highly important that internal conflicts arising within public organizations are handled appropriately. While conflict itself is not necessarily detrimental, if it is suppressed or mishandled, it often brings destructive effects in the form of loss of productivity, low morale of the workforce and fractured relationships (

Friedman et al., 2000). Managing conflicts in the public sector can be rather complicated, since unresolved issues can have multiple social implications that affect not only employees but also the governance quality and the community. Moreover, when conflicts are not resolved and employees are not involved in the process of conflict resolution and in decision making, they are likely to feel stressed and dissatisfied, which affects the climate of the organization and therefore the productivity. The services provided by the organization are poor and this can result in social and economic implications. In general, effective conflict resolution leads to a peaceful environment, social cohesion and stability in the community.

This paper integrates mentorship and mediation as proactive means of conflict prevention through leadership and conflict management in the Greek public sector, and this novel approach makes a significant contribution to the existing literature. While existing studies tend to focus on bureaucratic or top-down models of conflict resolution, little attention has been paid to preventive approaches combining mentorship and mediation within the specific cultural and administrative context of Greece. Additionally, the emphasis on the characteristics of a leader–mentor offers a practical framework for enhancing leaders’ abilities to detect and manage tensions before they become problematic, highlighting the importance of interpersonal skills in the profile of the modern leader. Therefore, the study examines conflict management beyond the framework of bureaucracy and explores its social implications, which constitutes an additional element of novelty.

Moreover, this research investigates the role that the supervisor/leader in the public sector plays in social cohesion and provides a new perspective that is essential for good governance, especially in a post-crisis country like Greece. The choice of Greece as the focus of this study is not incidental. The Greek public sector, shaped by a prolonged economic crisis and intense bureaucratic structures, presents a unique context where conflict resolution mechanisms are both urgently needed and structurally challenged. Examining conflict management in this environment offers valuable insights into how leadership approaches can operate under institutional pressure and socio-economic adversity. Finally, another novel approach is the research regarding the existence and use of digital tools and innovation in conflict resolution in the Greek public sector, a subject that is rarely examined in this context. In this regard, conflict prevention through inclusive leadership, mentoring, and the adoption of digital tools also contributes to the development of organizational resilience. The capacity of public institutions to anticipate, adapt, and respond to emerging tensions is increasingly seen as a critical aspect of long-term governance success—especially in fragile administrative environments. Consequently, this study, by offering theoretical expansion, localized insights, and empirical data, contributes both to academic literature and practical governance approaches.

Recognizing this theoretical and practical gap, the present paper proposes and empirically tests a novel hybrid framework that brings together inclusive leadership, mentorship, and digital tools for conflict management and social cohesion. Despite the growing recognition of the importance of conflict management in the public sector, existing research has primarily focused on either hierarchical, top-down approaches or isolated applications of mediation, mentoring, or digital innovation (

Barasa et al., 2018;

Duchek, 2020). Very few studies have systematically examined how these elements can be integrated into a comprehensive, hybrid model tailored to the realities of post-crisis Greek public administration. By doing so, the study moves beyond fragmented approaches and offers a novel perspective on how public organizations can enhance resilience and service delivery through the synergistic interaction of traditional and digital practices. This integrative approach aims to inform both theory and policy, providing actionable insights for strengthening social cohesion and resilience in public administration.

2. Literature Review

Exploring the interaction between Leadership, Mentorship and Mediation with Conflict Management provides insights into how leaders can prevent conflicts, foster productivity and build resilient communities.

For the purposes of this study, the following definitions are adopted to ensure conceptual clarity. “Leader” refers to individuals in formal positions of authority responsible for guiding teams or organizations toward collective goals, often shaping the overall culture and strategy (

Northouse, 2019). “Mentor” denotes a person—often but not always a leader—who provides personalized guidance, support, and knowledge transfer to colleagues or subordinates, focusing on professional development and psychosocial support (

Ragins & Kram, 2007). “Supervisor” is used here to indicate a direct line manager with responsibility for overseeing day-to-day work and performance of employees. While these roles may overlap in practice, especially in the public sector, this paper maintains the distinction to clarify their respective functions in conflict management, mentoring, and digital innovation. Throughout the manuscript, the terms are used according to these definitions.

2.1. Leadership and Mentorship in Conflict Prevention

Poor leadership style can escalate conflict or sometimes be the primary cause of it (

Barr & Dowding, 2022). Recent research on transformational leadership highlights the significance of mentoring in building cohesion within the organization (

Warrick, 2011). The leader–mentors help build individuals and teams through personalized mentoring and emotional support, unlike the traditional concept of managing. These leaders do not lead through conflicts but work to preclude them, establishing a trusting, respectful, and open environment with free-flowing communication. Mentorship is one of the intrinsic manners of leadership in leading or managing people by guiding, modeling, and giving support to them (

St. Clair & Deluga, 2006). In mentorship, more experienced employees offer guidance and transfer knowledge to their colleagues, providing professional growth and job satisfaction. At the same time, it is an effective way to motivate employees, with positive results in organizational performance (

Soegiarto et al., 2024). The term ‘mentor-leader’ refers to leaders who actively practice mentoring, as described in the literature review.

Research on this kind of leadership has proved to contribute to both personal and professional development (

Godden et al., 2014). In contrast to other top authority figures who rule, the mentor–leaders tend to invest in building a relationship founded upon trust, compassion, and a shared vision. Such relationships create the basis of a healthy working environment that facilitates the prevention of workplace conflict through open communication and mutual respect. Mentors are highly skilled in managing the personal and interpersonal factors that often underlie stakeholder conflicts. Through personalized coaching and by promoting open dialog, the mentor–leaders have the opportunity to anticipate and address potential conflicts at an early stage. To be successful in the prevention of workplace conflicts, mentor–leaders need training in negotiation skills alongside leadership coaching. One of the major roles of mentorship is to prepare future leaders and to develop the organization in terms of unity. More recently, mentorship’s contribution to conflict prevention has generated considerable interest (

Godden et al., 2014).

The leader generally faces three types of conflicts (

Fowler, 2013):

Interpersonal relationship conflict, which concerns communication between employees and may escalate due to misinformation, misinterpretation, personal interests, lack of understanding, or critical comments.

Work goal conflict, related to disagreement on goals or decision-making.

Conflict of procedural methods, concerning project implementation methods, delegation of responsibilities, and the marginalization of employees.

In this context, the leader should clarify the level at which conflict occurs. Usually, conflicts fall into the following three categories (

Thakore, 2013):

Dyadic conflict—between two individuals

Intragroup conflict—within a group

Intergroup conflict—between groups

Mentorship is not just the transfer of knowledge and experience to the mentee; it is the creation of a framework through which people can navigate the complexities of human relationships, organizational dynamics, and problem-solving. The leader–mentor plays a crucial role in shaping how teams approach challenges and, specifically, how they manage conflict before it becomes detrimental. The mentor–leader exists at the intersection of leadership, guidance, and personal development within the structure of organizational development. It differs from regular leadership, which is often characterized by authority and decision-making, whereas mentor–leaders are more collaborative. They carry the responsibility not only for inspiring team members but also for supporting their individual growth and well-being. The leader–mentor evolves both themselves and the management process, as their knowledge and experience contribute to employees’ professional and personal development (

Triantari, 2024). This growth-oriented approach makes mentor–leaders key figures in conflict prevention. With trust and communication, they can recognize early warning signs of potential conflicts, and intervene before these escalate, thus reinforcing a culture of psychological safety and cooperation (

Karadakal et al., 2015).

2.1.1. Mediation and Negotiation as a Preemptive Tool

Mediation is an alternative dispute resolution method. The aim of mediation is for the opposite parties to reach an agreement that satisfies their interests as much as possible (

Kohlhoffer-Mizser, 2020). To succeed in this goal, mediation creates a safe environment for all parties to be heard without judgment, thus providing empowerment and recognition (

Bush & Folger, 2012). With mediation, people are responsible for their own disputes and have the opportunity to produce their own outcomes, creating a sense of justice. Moreover, mediation allows individuals to participate in decision-making and reinforces community values (

Allport, 2021).

Bush and Folger (

2012) highlight this educational perspective of mediation, as it prepares individuals to handle conflicts more effectively each time they emerge while fostering a shared commitment to the community (

Bush & Folger, 2012). According to

Allport (

2016), the key principles of mediation practice are as follows:

Voluntariness—every party is free to participate and may withdraw at any stage

Confidentiality—the mediator is responsible for protecting the privacy of the process and of the parties involved

Party determination—the parties are autonomous in reaching their own decisions

Impartiality—the mediator must remain objective toward all parties (

Allport, 2016)

These principles demonstrate that mediation is not simply a technique, but a values-based approach that places human agency and respect at its core. This makes it particularly relevant in the public sector, where formal procedures often overlook interpersonal dynamics.

Mediation is not only a tool for resolving disputes but also a driver of cultural change regarding conflict resolution. The communication skills required for mediation go beyond being a method of work—they form the basis of a broader culture of interaction within organizations (

da Costa et al., 2022). The effort to listen, assess, and rethink all aspects of the opposing sides helps establish dialog as a norm in the organization (

Usmanova et al., 2021).

Furthermore, early intervention to resolve problems at their initial stage can help avoid future conflicts. In this way, mediation promotes conflict prevention (

Burns, 2014). The introduction of mediation into public administration represents an innovative approach that offers an alternative to the formalized procedures of the public sector (

Pawlowska et al., 2021). The mediator in public administration can either be an internal leader or staff member, or an external professional. According to

Allport (

2021), mediation as an early intervention method in the public sector is now integrated into policies related to equality, diversity, and dignity (

Allport, 2021).

Even when mediation is performed by internal staff members, it remains a structured process that requires proper training for mediators and conscious engagement from participants. In many Western countries, modern public policy supports this kind of early intervention because it prevents conflict escalation and protects workplace relationships (

Saundry & Urwin, 2021).

This approach reflects a shift from reactive conflict management to a proactive and human-centered resolution model. In hierarchical environments like public administration, such a shift is both challenging and transformative, as it requires redefining roles and processes. Mediation, therefore, does not simply resolve disputes—it redefines how organizations relate internally.

Moreover, mediation is not just an effective and efficient tool for conflict resolution—it also offers additional advantages, such as reducing social tension by creating a safe space for dialog and mutual understanding. Mediation is often time- and cost-effective, particularly in the workplace, where reaching an agreement becomes a priority (

Bushati & Spaho, 2013).

In mediation, negotiations between parties take place in a facilitated manner, so that the final agreement satisfies all interests (

Munduate et al., 2022). Negotiations that focus on the underlying interests, needs, and values of the parties tend to produce higher-quality agreements, enhance satisfaction, and foster cooperation by addressing the root causes of conflict, instead of relying on formal, rights-based resolution procedures (

Goldberg et al., 2017).

The training of modern leaders–managers in negotiation and mediation enhances their communication skills and their effectiveness in managing conflicts (

Koliopoulos et al., 2021). This highlights the dual role of the mentor–leader—not only as a decision-maker, but also as a facilitator of understanding and constructive dialog.

Negotiation is considered a structured set of techniques that certified mediators are trained to apply in order to assist parties in communication and problem-solving. Managers who apply negotiation techniques early can prevent the aggravation of conflict (

Mcconnon et al., 2010). This proactive application of negotiation situates leadership not merely as reactive management, but as early-stage conflict prevention embedded in daily interactions.

One of the fundamental principles of negotiation is the distinction between positions and interests. A position is what a person says they want, while interest refers to the underlying reasons, needs, or concerns behind that position. Often, conflict arises when individuals become entrenched in their positions.

Leader–mentors can play a key role by shifting the focus of their teams from fixed positions toward shared interests. This can be an effective way to de-escalate daily conflicts that arise between departments or even within the same team. As negotiations are essential in maintaining the organization’s sustainability, mentor–leaders can facilitate them in a way that satisfies both sides (

Eftimie et al., 2012).

Integrative negotiation, often referred to as interest-based or cooperative negotiation, is a method focused on developing win-win solutions. It rejects the win/lose logic and instead seeks mutually beneficial outcomes (

Benetti et al., 2021). This approach is especially suitable in the context of conflict prevention, as it encourages cooperation instead of competition.

Leader–mentors can coach their teams in integrative negotiation—helping them to identify common goals and explore creative solutions that meet everyone’s needs. By supporting a collaborative environment, the leader–mentor contributes to early conflict prevention by reducing tension before it escalates. This proactive stance is particularly important in resource-limited settings, such as public administration, where competition over responsibilities or recognition can easily turn into conflict.

By focusing on interests and collaboration in attaining win-win agreements, leader–mentors establish durable, long-term cooperation capable of preventing future conflicts. In this way, a mentor–leader helps teams shift from a reactive mindset to a proactive one—identifying and addressing potential disputes before they emerge. This shift reduces the overall incidence of conflict and enhances its quality, turning conflict into a productive process that can improve organizational resilience (

Benetti et al., 2021).

Such proactive leadership is especially valuable in the public sector, where rigid hierarchies and institutional constraints often hinder open communication. The mentor–leader’s ability to facilitate constructive dialogue helps to create a psychologically safe environment that allows teams to flourish even under pressure.

Another critical dimension in negotiation is the cultural background of the conflicting parties. Successful cross-cultural negotiation requires openness to new experiences and empathy. The negotiator-leader must foster this empathy, helping parties to recall shared experiences and avoid time pressures that prevent full understanding. Emotional dynamics, often shaped by culture, play a significant role in how conflicts escalate or resolve (

Avruch, 2022;

Weingart & Jehn, 2015).

In addition, the negotiator-leader must be aware of the presence of vulnerable groups within the organization—such as persons with disabilities, migrants, or individuals of different gender identities—who may negotiate differently and experience conflict in distinct ways. This awareness is crucial not only for ethical reasons but also for achieving effective and inclusive outcomes. Tailoring negotiation approaches to account for these differences reflects both emotional intelligence and leadership competence (

Triantari, 2020).

2.1.2. Challenges in Implementing Mentorship and Negotiation for Conflict Prevention

Merging leader mentorship and negotiation creates a powerful tool for conflict prevention, yet it is not without challenges. Leader–mentors must navigate various obstacles, including resistance at individual and organizational levels, as well as external pressures (

Hon et al., 2014). Therefore, conflict becomes part of social dynamics—it can either trigger positive change if managed properly, or lead to deterioration if left unresolved (

Siregar & Zulkarnain, 2022).

Organizational culture can also present barriers—especially in culturally diverse groups (

Gopalkrishnan, 2018). In some environments, competition is prioritized over collaboration, as success is often measured by individual performance rather than collective outcomes. In such settings, conflict is more likely to be viewed as a reflection of unhealthy competition than as a process that should be proactively managed or prevented.

Mentorship and negotiation can only be effectively implemented if the organizational culture is shaped by leadership committed to these principles. This requires clear articulation of how conflict prevention through mentorship and negotiation aligns with the organization’s strategic goals. For example, a mentor–leader might highlight that in a competitive sales environment, preventing internal conflicts enhances overall performance by improving communication and reducing stress (

Roberts et al., 2019). These investments yield substantial returns—stronger relationships, improved collaboration, and more sustainable performance (

Dunaetz, 2010). Thus, the mentor–leader reframes conflict prevention not as a cost but as a strategic advantage.

Taken together, these leadership approaches, when embedded in organizational culture, lay the groundwork for organizational resilience. Organizational resilience refers to the capacity of organizations to anticipate, prepare for, respond to, and adapt to incremental change and sudden disruptions in order to survive and thrive (

Duchek, 2020;

Linnenluecke, 2017). In the context of public sector conflict management, resilience is developed through leadership practices, effective mentoring, inclusive mediation, and the strategic adoption of digital tools (

Annarelli & Nonino, 2016). These elements help organizations not only to withstand crises or workplace disruptions but also to evolve and improve their social cohesion and service delivery (

Barasa et al., 2018). Previous studies highlight that resilient organizations cultivate adaptive cultures, promote trust, and enable employees to learn from adversity, thus reinforcing their ability to maintain performance under pressure (

Duchek, 2020;

Mallak, 1998). Integrating resilience into leadership and conflict management frameworks, therefore, provides a robust foundation for sustainable public administration.

2.2. Social Dimensions and Social Impact of Conflict

A conflict is characterized by complexity and shaped by multiple dimensions. Due to its dynamic nature, a conflict can evolve in unpredictable ways (

Malam, 2020). Conflicts carry social, psychological, economic, environmental, legal, and political implications. However, the social consequences of conflict remain underexplored in comparison to economic ones (

Haroon & Umair, 2024).

According to

Vanclay (

2002), conflicts often lead to predictable negative outcomes. These include disruptions in relationships—both at individual and group levels—which can become significantly harmful if left unresolved (

Menchaca, 2024;

Vanclay, 2002). Conflict reduces the quality of daily life by disrupting economic and social activity, leading to lower productivity and deteriorating workplace environments. In more severe cases, unresolved conflicts may escalate into violence. Fear, uncertainty, and a loss of trust affect social cohesion, while the breakdown of social relations can trigger psychological, sociological, and even economic repercussions (

Vanclay, 2002).

However, conflicts can be beneficial—especially when an effective conflict management culture is embedded within the organization. Conflict management refers to resolving disputes in a way that the constructive aspects outweigh the destructive ones. The goal is to maximize the benefits and minimize the costs of conflict (

Conbere, 2001;

Van de Vliert & De Dreu, 1997).

According to

Barrow (

2010), social relations can improve through the process of resolution, contributing to the strengthening of social capital in the long term (

Barrow, 2010). Conflicts can spark group development and represent a turning point in the group’s evolution towards deeper connection and cooperation (

Vinokur et al., 2024).

Moreover, conflicts often initiate organizational changes, pushing outdated practices to be revised or abandoned (

Van de Vliert & De Dreu, 1997).

McKibben (

2017) emphasizes that conflict and change are intertwined (

McKibben, 2017). A positive approach to conflict can lead to increased productivity and foster critical thinking. On the other hand, unplanned or imposed changes often generate conflict due to resistance, uncertainty, and misunderstanding.

These dynamics highlight the link between conflict and democratic principles—particularly the freedom to express dissenting opinions. When disagreement is acknowledged and addressed respectfully, destructive tendencies are reduced, and dialog becomes a driver for growth (

Prenzel & Vanclay, 2014).

2.3. The Role of Technology and Innovation in Conflict Management

The rapid pace of technological advancement is shaping the world in constant transformation. As a result, it becomes essential for organizations to adopt innovation in order to achieve sustainability and growth (

Zervas & Stiakakis, 2024).

In the literature, innovation is often associated with the private sector, based on the assumption that public administration lacks the motivation to innovate. Bureaucratic structures in public organizations tend to resist change, creating barriers to innovation by favouring traditional processes. However, existing research indicates that the desire to innovate exists in public administration as well, though it varies depending on each organization’s leadership and strategic orientation (

Demircioglu & Audretsch, 2017).

Recent studies have highlighted the impact of digital transformation in the public sector, particularly in improving public services through the integration of new technologies (

Fischer et al., 2021). Understanding conflict management approaches in connection with innovation is therefore essential in unlocking the potential of public sector reform (

Meijer & De Jong, 2020).

The aim of digital transformation in public administration is not only to enhance efficiency in service delivery but also to optimize decision-making by supporting human judgment with data-driven tools (

Mergel et al., 2023). These changes reshape both internal procedures and external relations, generating broader organizational and social change (

Haug et al., 2024).

According to

Slimane (

2015), “social change is the result of leadership actions”. In this light, public sector leaders are increasingly expected to address social issues through innovation and digital engagement (

Slimane, 2015). This expectation connects directly to the evolving role of the mentor–leader, who must now integrate digital fluency into their leadership style and use technology not only for operational efficiency but also for inclusive conflict management.

In this context, the role of advanced technology and innovation in conflict management has become increasingly relevant. Digital tools offer new ways to analyze data, predict escalation, and enhance mutual understanding between conflicting parties. Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems can process and interpret large datasets at high speed, while virtual mediators can facilitate online dispute resolution in real time, offering impartial guidance and reducing tensions.

Blockchain technology may be used to record mediation agreements in workplace disputes, thereby increasing trust and transparency. Digital platforms also accelerate conflict resolution by supporting virtual communication (e.g., video conferencing), while Virtual and Augmented Reality technologies allow public sector leaders and mediators to engage in realistic simulations, enhancing empathy and negotiation skills (

Omowon, 2024).

At a broader level, governments use social media to promote citizen engagement and counter misinformation that could escalate into social conflict. E-government platforms support transparency, efficiency, and public participation, helping to prevent governance-related disputes.

The growing need for digital platforms is partly driven by remote work models and geographical isolation. These platforms connect conflicting parties with professionals while fostering a broader community through webinars and collaborative spaces. They promote transparency through clear protocols and ensure inclusivity by giving all stakeholders—women, youth, marginalized groups—a voice in the mediation process.

According to

Putra et al. (

2024), an Android-based conflict resolution e-learning application in Indonesia achieved 95% user satisfaction, highlighting the potential of such tools in education and training (

Putra et al., 2024). These tools not only support conflict resolution in real time but also empower individuals to manage conflict constructively in diverse contexts.

However, despite the advantages, challenges persist. Concerns about data use, digital surveillance, and the security of sensitive information must be addressed. Additionally, ethical dilemmas arise from the use of AI systems that may reproduce bias or fail to interpret complex social dynamics—particularly in multicultural environments (

Omowon, 2024).

Given these limitations, a hybrid framework emerges as the most effective approach. Combining digital technologies with traditional, face-to-face methods allows for context-sensitive conflict resolution that retains the human element. In this way, the mentor–leader remains both technologically adaptive and personally engaged—ensuring that innovation supports, rather than replaces, inclusive leadership.

2.4. Leadership Approaches for Social Inclusion

The leader’s role is critical in shaping employees’ perception of inclusion within the workplace. Leaders are responsible for implementing the organization’s approaches in ways that actively promote inclusion (

Nishii & Leroy, 2022). As an approach, inclusion has a strong impact on advancing organizational objectives while also benefiting employee well-being.

Within the organizational context, however, leaders may face obstacles in their efforts to adopt inclusive practices (

Shore & Chung, 2022). Nevertheless, it remains their responsibility to cultivate values such as diversity, acceptance, equity, and self-worth—all essential for fostering inclusion. Leadership approaches for social inclusion aim to create an environment where empathy and participation prevail, and where employees feel a sense of belonging and value regardless of their background (

Ferdman, 2014).

According to

Nishii (

2013), the core dimensions of an inclusive environment include: perceived fairness, cultural integration of differences, and inclusive decision-making (

Nishii, 2013). These dimensions form the foundation for building trust and engagement within diverse teams and are particularly relevant in public sector settings, where uniform policies often risk overlooking individual experiences.

Public leaders should incorporate inclusiveness into their organizational vision and communicate this commitment both internally and externally (

Hambrick & Mason, 1984). Establishing structures that elevate diverse voices, promote open dialog, and ensure feedback mechanisms support participatory decision-making.

Furthermore, when employees are encouraged to share their ideas in direct conversations, they experience a sense of value and uniqueness (

Chrobot-Mason & Aramovich, 2013). According to

Weiss et al. (

2018), when leaders move beyond hierarchical structures, trust and psychological safety are fostered—enabling employees to offer constructive input on organizational matters (

Weiss et al., 2018). This enhances engagement and motivates individuals to contribute time, effort, and creativity to the organization’s goals (

Fagan et al., 2022).

Through equitable treatment and inclusive policies, leaders give employees—regardless of their background—the opportunity to feel authentic and accepted. This includes bias-free recruitment, empowerment of marginalized groups, and transparent advancement processes. However, fairness does not imply neutrality. Instead, it requires actively challenging assumptions and stereotypes, and recognizing people as they are (

McCluney & Rabelo, 2019). Equity means meeting individuals’ distinct needs, not simply treating everyone the same.

Inclusive leaders support employees not only in fulfilling organizational goals, but also in realizing their personal potential. A supportive environment grounded in equal opportunity contributes to employee retention and satisfaction. Psychological empowerment has also been linked to innovation, and can be especially meaningful for minority employees (

Chrobot-Mason & Aramovich, 2013;

Shore & Chung, 2022).

Ultimately, leadership approaches for social inclusion are most effective when they cultivate a dynamic work environment defined by empathy, equity, openness, justice, participation, and mutual respect. In such an environment, employee well-being is elevated—and the organization itself becomes more resilient and adaptive.

2.5. Research Questions

Within the public sector, leadership practices that emphasize empathy, communication, and proactive conflict management play a crucial role in promoting social cohesion. Transformational leaders and mentor–leaders are especially well-positioned to cultivate trust, inclusiveness, and collaboration in diverse work environments. As conflicts often arise from poor communication, exclusion, or hierarchical rigidity, leadership approaches that integrate mediation techniques can actively prevent escalation and foster a more united organizational culture. Exploring how such leadership models influence cooperation and social harmony in the public sector is essential to understanding their potential impact on effective governance.

Mentorship has gained recognition as a strategic leadership tool for promoting equity, empowerment, and inclusive participation in the workplace. In multicultural environments, especially within the public sector, mentor–leaders can support individuals from vulnerable or traditionally excluded groups by providing guidance, access to opportunities, and psychological safety. This form of personalized support fosters both personal growth and organizational integration. Investigating the extent to which mentorship contributes to the empowerment of such groups provides insight into how leadership approaches can promote diversity and cohesion in complex public settings.

Digital transformation in the public sector has introduced new tools for managing and preventing conflict, ranging from AI-supported platforms to virtual dialog environments. These technologies enable faster resolution processes, enhance transparency, and improve accessibility—particularly for remote or underrepresented populations. In Greece, where public administration faces both bureaucratic rigidity and socio-economic pressure, the integration of innovation into conflict resolution mechanisms remains an emerging yet underexplored field. Investigating how digital tools contribute to mediation and conflict prevention in this context sheds light on the broader potential of innovation to support inclusive and responsive governance.

Poorly managed conflicts in the public sector can generate far-reaching social consequences, affecting both internal dynamics and wider community relations. Beyond reduced productivity or workplace dissatisfaction, unresolved conflict can undermine social cohesion, exacerbate inequalities, and diminish citizens’ trust in public institutions. While the economic costs of conflict have been widely studied, its social dimensions—such as psychological strain, exclusion, or the erosion of democratic dialog—remain less examined. Investigating these impacts is essential for understanding the broader implications of conflict management in governance, especially in contexts where public trust and participation are critical to organizational legitimacy.

2.6. Conceptual Research Framework

Building upon the preceding literature review, the present study proposes a comprehensive conceptual framework that explains how leadership and mediation approaches, mentorship, and the adoption of digital tools jointly influence social cohesion and organizational resilience in the Greek public sector. This framework is grounded in previous research emphasizing the mediating role of mentorship between leadership and digital innovation (

Brooman & Darwent, 2014;

Ragins & Kram, 2007), as well as the impact of digital tools on social and organizational outcomes (

Bertot et al., 2012;

Van Dijk, 2021).

The model posits the following hypothesized relationships:

Leadership and mediation approaches positively influence mentorship within organizations.

Effective mentorship facilitates the adoption and meaningful use of digital tools.

The adoption of digital tools strengthens social cohesion and mitigates the negative impacts of inadequate conflict management.

The interaction of these elements collectively supports the development of organizational resilience.

Each of the study’s research questions (RQs) is mapped onto specific relationships within the conceptual framework:

RQ1 investigates the direct and indirect effects of leadership and mediation on social impact.

RQ2 explores the role of mentorship in empowering vulnerable social groups and promoting social cohesion, both directly and via digital tools.

RQ3 examines how the adoption of digital tools improves mediation and conflict prevention, thus enhancing social impact.

RQ4 addresses the overall social consequences of inadequate conflict management, as reflected in the cumulative effects on social impact and organizational resilience.

The conceptual framework is visually presented in

Figure 1, which illustrates the hypothesized direct and indirect relationships among the main constructs of the study, clearly indicating how each research question corresponds to specific paths within the model.

In summary, this integrative framework clarifies the mechanisms through which inclusive leadership, mentorship, and digital innovation interact to promote social cohesion and organizational resilience in public administration. It serves as the theoretical and empirical foundation for the study’s research hypotheses and subsequent statistical analysis, as outlined in the

Section 3.

3. Materials and Methods

This research was based on modern quantitative methods of data analysis, in order to examine in depth, the complex relationships among leadership, mentoring, the use of digital tools, and the social impact in the public sector. For this purpose, the PLS-SEM method was selected, which is suitable for the investigation of theoretical models with multiple dimensions and allows the analysis of both direct and indirect relationships. This methodology fits the philosophy of the article, as it focuses on a holistic understanding of the multifaceted factors which influence conflict management and social cohesion in the public sector (

Hair et al., 2022).

This method is considered more appropriate compared to others, such as simple regression or correlation analysis, because it makes it possible to study simultaneously many paths between concepts and to analyze latent variables which are measured with multiple questions. In addition, PLS-SEM can be applied to data which do not follow normal distribution, and it is ideal for questionnaires with Likert scales, like ours. In this way, we can obtain a more complete and reliable picture of the relationships that are of our interest (

Hair et al., 2021).

The quantitative approach was chosen because it facilitates an objective and systematic measurement of abstract concepts such as leadership approaches, mediation effectiveness, and social cohesion, while minimizing potential biases inherent in qualitative methods. Furthermore, this method supports inductive reasoning, thereby allowing the results obtained from our sample to be generalized to the wider population of public sector employees (

Krosnick, 2018).

The questionnaire was distributed electronically via Google Forms, which proved to be both user-friendly and efficient. Prior to completion, participants received an introductory note explaining the purpose of the study, emphasizing that participation was anonymous and voluntary, and providing an estimate of the time required to complete the questionnaire. In addition, strict measures were implemented to ensure data confidentiality and compliance with ethical standards.

Data collection was conducted from February 2024 to December 2024. During this period, electronic questionnaires were distributed, and periodic reminders were sent to encourage timely responses. All responses were collected anonymously, and protocols were maintained throughout to ensure data quality and consistency.

Participants were recruited using a snowball sampling method. Initial contacts were made with key informants in public administration, who then referred colleagues from various departments and regions. The snowball sampling method was selected because it is particularly effective for accessing professionals within complex organizations such as the Greek public sector, where traditional probability sampling is often infeasible due to the lack of comprehensive staff directories and potential reluctance to participate in official research. By leveraging trusted peer networks, this approach increased response rates and ensured the inclusion of diverse departments and roles (

Goodman, 1961;

Naderifar et al., 2017).

Although snowball sampling is effective for targeting specific professional populations, it may limit generalizability due to potential selection bias. To partially mitigate this, the sample was diversified by including respondents from multiple public sector settings (municipalities, ministries, regional and decentralized administrations). Future studies may consider combining snowball with random sampling techniques to further enhance external validity.

Throughout the survey, the terms ‘leader’, ‘mentor’, and ‘supervisor’ are used in accordance with the definitions outlined in

Section 2. For the purposes of questionnaire items, the compound ‘leader/supervisor’ refers to any employee with formal or delegated responsibility for team management, encompassing both direct supervisors and higher-level leaders, in line with the organizational structure of the Greek public administration. In cases where the term “mentor” is used, it specifically refers to those employees (often but not exclusively leaders or supervisors) who provide personalized guidance, professional development, and support, as outlined in the literature review. For brevity and based on the structure of the Greek public sector, the term ‘leader/supervisor’ in the questionnaire refers to individuals with formal responsibility for team management, encompassing both top-level leaders and direct supervisors as defined in the literature review.

The questionnaire consisted of five distinct sections (

Table 1):

- ⮚

Demographic information (four closed-ended items);

- ⮚

Leadership and mediation approaches for social cohesion (ten Likert-type items);

- ⮚

Guidance and empowerment of vulnerable groups (ten Likert-type items);

- ⮚

Use of digital tools for mediation and conflict prevention (ten Likert-type items);

- ⮚

Social consequences of inadequate conflict management (ten Likert-type items).

Each Likert-type item was rated on a five-point scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree). For each thematic section, a composite score variable was created by averaging the responses to the ten items, where higher scores indicate a stronger presence of the respective dimension.

The research sample comprised a total of 203 employees from the public sector. Specifically, respondents were drawn from municipalities, ministries, regional administrations, and decentralized authorities, primarily from departments with a technical or administrative focus (e.g., engineers, administrative staff, and foremen). The majority of the sample consisted of women aged 50–59 with over 20 years of experience in the public sector, and most held a postgraduate degree.

The statistical analysis of the data was performed with the software SMART PLS, version 4.1.1.2, which was used for the structural analysis (SEM), the estimation of the relationships among the latent variables, and the significance testing through bootstrapping. For the description of the sample and the calculation of basic descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, frequencies), we also used the program Jamovi (version 2.4.8), which helps with the fast analysis and visualization of the data.

The check of validity and reliability of the measurements is considered necessary in every research effort, so as to ensure that the tools used really measure what they are supposed to measure and that the results are stable and can be repeated. Especially in studies based on questionnaires with multiple questions, the examination of such indicators is important to strengthen the trust in the conclusions that come from the analysis (

Kline, 2023).

In this study, we conducted a systematic check of internal reliability and convergent validity for each one of the four latent variables of the model (

Table 2). For measuring the internal consistency of the items, we used Cronbach’s alpha, which in all cases appeared extremely high (from 0.941 to 0.983). Such high values indicate that the individual questions in each section effectively measure the same theoretical construct (

Hair et al., 2021).

Additionally, we examined two types of composite reliability: rho_a and rho_c (Composite Reliability). The rho_a is considered a more “strict” indicator, as it takes into account the contribution of each item separately, while rho_c estimates the overall reliability of the construct, based on the average loadings of the items. Both indicators in all variables were above 0.94, with the highest values being in the “Social Impact” construct (rho_a = 0.983, rho_c = 0.985). This consistency between the two indicators gives extra confidence in the reliability of the measurements (

Ringle & Sarstedt, 2016).

The AVE indicator (Average Variance Extracted) was used for the check of convergent validity, that is, how well the items of each construct explain the underlying concept. All AVE values were above the minimum acceptable limit of 0.5, ranging from 0.653 in “Leadership and Mediation” to 0.864 in “Social Impact”. This means that most of the variance in the items is due to the relevant factor and not to error or random influences.

Overall, the indicators of

Table 2 show that the research tool has very high reliability and validity, a fact which gives special importance and safety to the statistical analyses and to the conclusions of the study.

The HTMT values (

Table 3) calculated between the variables are at generally acceptable levels, since according to the literature, thresholds up to 0.85 or even 0.90 are considered acceptable for discriminant validity. For example, the value 0.857 which appears between the dimensions “Social Impact” and “Digital Tools” shows that these two concepts are related, as expected based on the theory and the structure of the model, but at the same time, they keep their distinct character. The other HTMT values (e.g., 0.764, 0.806, 0.611, 0.562, 0.677) are clearly below the limit and confirm the discriminant validity of the constructs. Overall, the results of the table show that the main variables of the model, although they have functional connections between them, still remain separate conceptual entities, which adds extra validity to the measurement and analysis.

The advantage of HTMT is that it can detect possible overlaps between different constructs more effectively compared to traditional indicators. In this way, it is ensured that each conceptual dimension of our study is really distinct and measures a separate theoretical content, something that increases the validity of the model’s conclusions (

Ringle & Sarstedt, 2016).

Additionally, the check of discriminant validity was performed with two complementary methods: the Fornell-Larcker criterion (

Table 4) and the HTMT indicator (

Table 3). The parallel use of both indices is now considered necessary, since the Fornell-Larcker offers a traditional but recognized approach, while the HTMT is a newer and more sensitive method that can detect overlaps between latent variables, even when the Fornell-Larcker is satisfied. With this combined check, it is ensured that each conceptual dimension remains distinct and measures unique content, which overall increases the validity of the model (

Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

As shown in the table, each value on the main diagonal (for example, 0.898 for “Digital Tools”, 0.930 for “Social Impact”, etc.) corresponds to the square root of the AVE for each construct. In order to keep the discriminant validity, this value must be greater than any correlation of the same construct with any other (that is, greater than the values in the same row or column, except the diagonal).

For example, in the “Social Impact” dimension, the value on the diagonal is 0.930, while the correlations with the other constructs are significantly lower (0.839, 0.541, 0.660). The same pattern is observed in the other dimensions, which confirms that each variable keeps its autonomy and is not conceptually overlapped by the others.

Overall, the analysis with the Fornell-Larcker table confirms that the constructs of the study, beyond their functional relation, remain distinct. The compliance with both criteria (Fornell-Larcker and HTMT) secures the discriminant validity of the model and gives reliability to the results of the statistical analysis.

In the context of evaluating the overall fit of the model to the data, a model fit check was carried out using the main indicators proposed in the literature for PLS-SEM (

Table 5). The SRMR indicator (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual) for the saturated and the estimated model showed very low values (0.035 and 0.040, respectively), much lower than the threshold of 0.08 which is considered acceptable, something that shows a very good fit of the model to the data. Similarly, the values of d_ULS, d_G, and NFI (0.892) are at acceptable levels, confirming the overall appropriateness of the structural model.

Additionally, the R-square (R

2) values produced by the structural model were also checked (

Table 6), showing the percentage of variance of each dependent latent variable that is explained by the independent variables in the model. Specifically, the “Digital Tools” dimension shows R

2 = 0.549, which means that about 55% of its variance is explained by the factors included in the model. For the variable “Mentorship”, R

2 is 0.594, indicating that the model manages to explain almost 60% of the variance in mentoring. Finally, for “Social Impact”, R

2 reaches 0.703, which means the model explains more than 70% of the total variance in this dimension.

It is worth noting that the above values are considered satisfactory for research in social sciences and behavioral models, as they show that the proposed model has significant predictive power regarding its dependent variables.

The last indicator used is the f2. The f2 index is used to evaluate the effect size of each independent variable on the dependent variables of the model. Specifically, the f2 value shows to what extent a variable really contributes to explaining the variance of the dependent variable, beyond what is already explained by the other variables in the model.

In the table from the analysis (

Table 7), we can see that:

The effect of “Leadership and Mediation” on “Mentorship” shows f2 = 1.461, which is characterized as very high effect size (since values above 0.35 are considered large in the literature).

The effect of “Mentorship” on “Digital Tools” is f2 = 1.215, also indicating a very strong effect.

Finally, the effect size of “Digital Tools” on “Social Impact” is f2 = 2.369, which is considered extremely high.

These values overall indicate that the relationships examined in the structural model are not only statistically significant but also practically strong, offering a well-supported explanation of the effects among the main variables of the study.

In summary, the combination of a robust questionnaire, a diverse sample, and rigorous statistical analysis enhances the methodological strength of this research, supporting the generalizability of the findings to the broader population of Greek public sector employees.

4. Results

This chapter presents the main findings of the study based on the analysis of the collected data. The results are organized according to the structure of the research tool and the research questions posed. Initially, the demographic characteristics of the sample are outlined, followed by descriptive statistics and inferential analyses addressing the main variables of interest. The purpose is to highlight patterns, correlations, and potential interpretations relevant to leadership, mediation, and conflict management practices in the Greek public sector.

4.1. Demographic Profile of the Sample

As shown in

Table 8, the gender distribution is nearly balanced, with women representing 51.2% of the sample and men 48.8%. This gender parity provides a representative basis for analysis, particularly since previous research has indicated that gender may influence leadership styles and perceptions of conflict management practices (

Dwiri & Okatan, 2021).

According to

Table 9, a significant majority (60.1%) of respondents are between the ages of 50 and 59, while only 3% are under 40. This reflects the broader demographic profile of the Greek public sector, which is characterized by an aging workforce (

European Commission, 2018). Similar trends have been reported in EU-level studies on public administration (

European Commission, 2018), highlighting the necessity of adapting leadership approaches to an older demographic with institutional knowledge and specific professional needs.

Table 10 shows that 69% of respondents have more than 20 years of experience in the public sector, while 21.7% have served for 11 to 20 years, and 9.4% have 10 years or less. This extensive experience suggests that the participants are deeply embedded in public sector operations and are likely familiar with both traditional bureaucratic models and emerging management reforms. Previous studies have emphasized that long-serving public employees tend to demonstrate strong organizational commitment but may also exhibit resistance to innovation—an important consideration in exploring digital mediation tools (

Moussa et al., 2018).

Table 11 illustrates that 57.6% of participants hold a master’s degree, 29.1% a university diploma, 7.4% a secondary education degree, and 5.9% a doctoral diploma. The high level of academic qualification enhances the validity of the collected data and allows for more sophisticated insights into leadership, inclusion, and organizational resilience. Similar educational profiles have been noted in other European studies, where advanced degrees among public servants are becoming increasingly common (

Hägerström, 2023).

4.2. Thematic Analysis of Key Variables

In this section, the research findings are presented in direct connection to the thematic axes and the corresponding research questions. The descriptive statistics of participants’ responses are organized into four core dimensions, each reflecting a distinct aspect of leadership, mediation, and conflict management in the public sector. Through the analysis of these variables, deeper insights are offered into the prevalence, effectiveness, and perceived outcomes of relevant organizational practices.

The analysis of

Table 12 shows that leadership and mediation approaches promoting social cohesion are applied at a moderate level across public sector organizations. Respondents most strongly agree with the presence of open and regular communication between supervisors and staff (M = 3.98), which aligns with the findings of

Nakamura and Milner (

2023), who highlights communication as a foundational pillar of inclusive leadership (

Nakamura & Milner, 2023). In contrast, respondents report less agreement that conflicts are addressed promptly by leadership (M = 3.10), suggesting that while communication channels may exist, conflict responsiveness remains suboptimal.

This result echoes

Gagel (

2021), who argues that in bureaucratic structures, even well-meaning leaders may lack the agility to manage tensions in real time. The relatively lower score on proactive conflict management indicates a gap between leadership intention and execution, which could undermine team cohesion in high-pressure public environments (

Gagel, 2021).

As shown in

Table 13, respondents report moderate agreement with all statements related to mentorship and the empowerment of vulnerable social groups. The highest score (M = 3.60) indicates that supervisors are perceived to acknowledge and address the needs of vulnerable employees—a finding consistent with

Heaphy and Dutton (

2008), who emphasize the role of leader empathy in promoting workplace inclusion (

Heaphy & Dutton, 2008).

However, the lower score regarding the promotion of decision-making participation among vulnerable groups (M = 3.21) suggests that inclusion efforts may remain symbolic rather than structural. This resonates with findings by Mor

Barak and Levin (

2002), who argue that tokenistic inclusion can mask deeper participation inequalities in organizational settings (

Barak & Levin, 2002).

The overall pattern reflects progress toward equity but also reveals areas where mentorship could be more targeted and systemically embedded.

Table 14 highlights a moderate but uneven adoption of digital tools for mediation and conflict prevention. While digital technologies are seen as beneficial for transparency and climate-building (M = 3.31), respondents strongly disagree that they receive appropriate training in their use (M = 2.24). This discrepancy suggests a technological adoption gap, consistent with

Ojiako et al. (

2024), who identified that in many public sector organizations, innovation outpaces employee readiness (

Ojiako et al., 2024).

Furthermore, the low mean scores on early detection of tension through technology (M = 2.38) and conflict prevention via digital tools (M = 2.27) underline the need for more structured digital integration approaches. As suggested by

Lopes et al. (

2023), digital transformation must be accompanied by robust training and inclusive design to be effective in conflict-sensitive environments (

Lopes et al., 2023).

Table 15 presents a strong consensus among respondents regarding the social impacts of poor conflict management. The highest-rated items relate to stress and burnout (M = 4.58), reduced trust (M = 4.44), and deteriorating team performance (M = 4.42), indicating a clear recognition of the destructive consequences of unresolved conflicts.

These findings reinforce the argument by

Paresashvili et al. (

2021) that conflict mismanagement undermines both individual well-being and organizational resilience (

Paresashvili et al., 2021). Interestingly, even less emphasized impacts, such as the intensification of social inequalities (M = 4.05), are still rated quite high, suggesting that public servants are acutely aware of the broader societal repercussions of workplace tensions.

Table 16 summarizes the four core score variables derived from the Likert sections. The highest overall agreement concerns the social consequences of inadequate conflict management (M = 4.32), followed by leadership and mediation approaches (M = 3.42) and mentorship practices (M = 3.36). The lowest score is attributed to the use of digital tools (M = 2.92), which, although close to the moderate level, signals an area requiring urgent attention.

These results align with the broader literature, which suggests that while traditional leadership approaches have matured, the integration of digital innovation in conflict prevention remains underdeveloped, particularly in bureaucratic and resource-constrained public sectors like Greece (

Lotsis et al., 2024).

4.3. Analysis and Results of the Structural Model (PLS-SEM)

Next, the analysis of the structural model was performed using the PLS-SEM method, aiming to investigate the relationships among the main variables of the research. This specific model allows the simultaneous check of the effects between the thematic sections, taking into account both direct and indirect relationships. The results are presented in detail below, based on the paths that were examined among the four main dimensions of the questionnaire.

The structural model used in the analysis was built according to the main dimensions of the questionnaire. Specifically, four latent variables were designed, each one represented by ten Likert-type questions (

Table 17). These variables are: “Leadership & Mediation”, “Mentorship”, “Digital Tools”, and “Social Impact”. In this model, every latent variable is connected with the corresponding observed items, and the relationships between the variables were designed to reflect the research questions of the study.

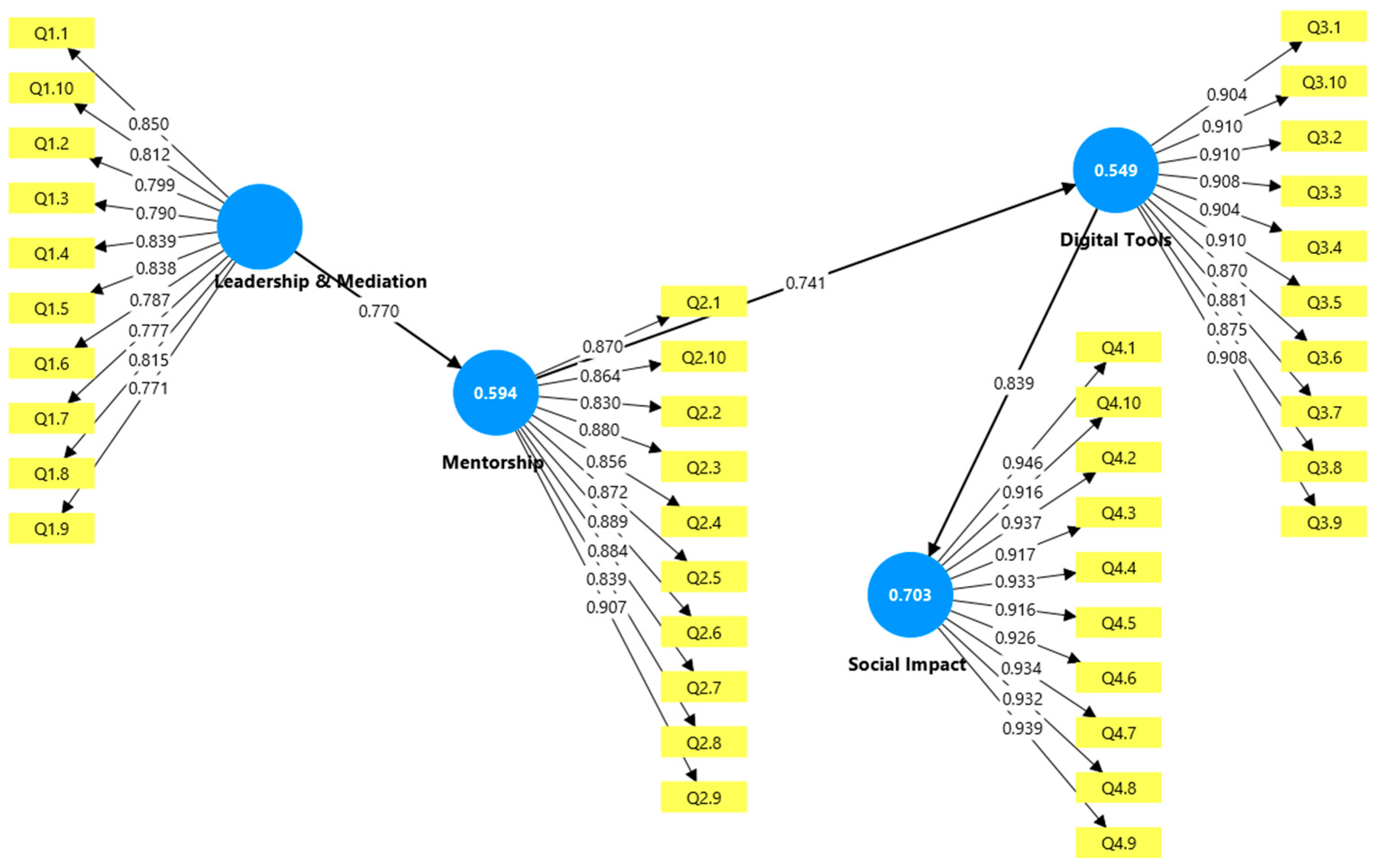

The graphical representation of the model (

Figure 2) clearly shows the paths between the main dimensions, the levels of association, and the contribution of each question to its latent variable.

The analysis of the structural model shows very clear and strong relationships among the main variables, as seen by the path coefficients which are significant and have high values. Each relationship is examined separately below, with relevant support from the international literature (

Table 18).

The effect from “Leadership and Mediation” to “Mentorship” is very strong (0.770,

p < 0.001). Practically, this means that when leadership practices and mediation are improved in an organization, the function of mentoring also increases. In essence, a leadership style that pays attention to mediation and supports its members also encourages the development of mentoring networks. The literature has highlighted this; for example,

Allen et al. (

2004) found that leadership practices emphasizing mediation and inclusion create ground for more systematic mentoring, especially in the public sector (

Allen et al., 2004). Similarly,

Karakas and Sarigollu (

2013) have shown that leadership focusing on human relations and collaboration promotes mentoring in the workplace (

Karakas & Sarigollu, 2013).

The relationship from “Mentorship” to “Digital Tools” also appears very strong (0.741,

p < 0.001). In practice, this means that when mentoring works well, it facilitates the use of digital tools by the members of the organization. Basically, mentors help the less experienced with using new technologies and support the transition to digital environments. Relevant research, such as

Brooman and Darwent (

2014), supports that mentoring programs in education and organizations significantly help the adoption of technological tools (

Brooman & Darwent, 2014). Similar results are presented by

Ragins and Kram (

2007), where mentoring is connected to higher adaptability to technological changes (

Ragins & Kram, 2007).

The effect from “Digital Tools” to “Social Impact” is even higher (0.839,

p < 0.001). This shows that the more digital tools are used, the more the social impact of an organization or a group is increased. Digital tools are not only technical means, but they facilitate cooperation, transparency, and participation, directly affecting social cohesion and the development of social actions. This relationship is supported by many studies, such as

Bertot et al. (

2012), who showed that the use of digital media increases social participation and public value (

Bertot et al., 2012). At the same time,

Van Dijk (

2021) and

Gu et al. (

2023) emphasize that digital tools enhance the inclusion of vulnerable groups and increase social cohesion (

Gu et al., 2023;

Van Dijk, 2021).

The analysis of the path coefficients, as presented in

Table 19, revealed strong and statistically significant direct relationships among the main variables of the model. To further investigate the mechanism by which the key dimensions interact, a complementary mediation analysis was conducted using the SmartPLS software (version 4.1.1.2). This methodological choice was based on its capability to capture both direct and indirect effects, even in complex models with sequential variables. The estimation of specific indirect effects was performed with bootstrapping (5000 repetitions) to ensure the accuracy and statistical validity of the results.

The mediation analysis results confirmed the importance of indirect relationships. Specifically, it was found that mentorship exerts a significant indirect effect on Social Impact through the enhancement of Digital Tools usage, with a coefficient of 0.621 (p < 0.001). Furthermore, the composite path starting from Leadership and Mediation, passing through mentorship and Digital Tools, and ending at Social Impact also shows a high value (0.479, p < 0.001). Finally, Leadership and Mediation indirectly influences the adoption of Digital Tools via mentorship (0.571, p < 0.001). All indirect effects are statistically significant, as reflected in the respective t-statistics and p-values.

These findings are fully consistent with the international literature, which highlights the role of mediating mechanisms in strengthening organizational outcomes (

Brooman & Darwent, 2014;

Preacher & Hayes, 2008). In particular, the gradual enhancement of social impact through the adoption of digital tools and the function of mentorship, as confirmed in the present study, has emerged as a central axis in contemporary approaches to organizational development and social cohesion (

Bertot et al., 2012;

Gu et al., 2023). Overall, the model analysis demonstrates that mediation processes, combined with direct effects, compose a robust framework for enhancing social cohesion through leadership, mentorship, and technology.

Subsequently, the necessity arose to evaluate the predictive ability of the structural model. In this context, the PLSpredict procedure was applied, as recommended in the recent literature for PLS-SEM models. This method is based on the logic of cross-validation, where the sample data are repeatedly divided into training and testing subsets, thus allowing reliable estimation of the model’s predictive performance on out-of-sample data. For this analysis, 10 folds and 10 repetitions were chosen, while the random seed was fixed to ensure the reproducibility of the results (

Hair et al., 2022;

Shmueli et al., 2016).

The results of the PLSpredict procedure are summarized in

Table 20. The Q

2predict values for the main latent variables were positive and significantly high: for Digital Tools the value was 0.339, for mentorship 0.586, and for Social Impact 0.284. These values indicate that the model possesses substantial predictive ability for all main dependent variables, since according to the literature (

Shmueli et al., 2016), Q

2predict > 0 indicates that the model outperforms the naive benchmark and provides reliable prediction on new data.

Additionally, the accompanying error metrics (Root Mean Square Error—RMSE and Mean Absolute Error—MAE) were at relatively low levels (e.g., RMSE for mentorship = 0.652, MAE = 0.428), which further supports the conclusion that the model achieves not only statistical but also practical accuracy in its predictions.

These findings fully align with recent research highlighting the value of PLSpredict and Q

2predict indices as key tools for assessing the practical reliability of PLS-SEM models. Particularly in studies focusing on organizational or social phenomena, the model’s ability to reliably predict critical indicators, such as social impact or technological adoption, is now considered an essential prerequisite for evaluating the usefulness of the theoretical framework (

Hair et al., 2022;

Shmueli et al., 2016).

Overall, this analysis demonstrates that the current model shows strong predictive relevance and can be effectively used both for interpretation and prediction of organizational and social outcomes, reflecting best practices in the international literature.

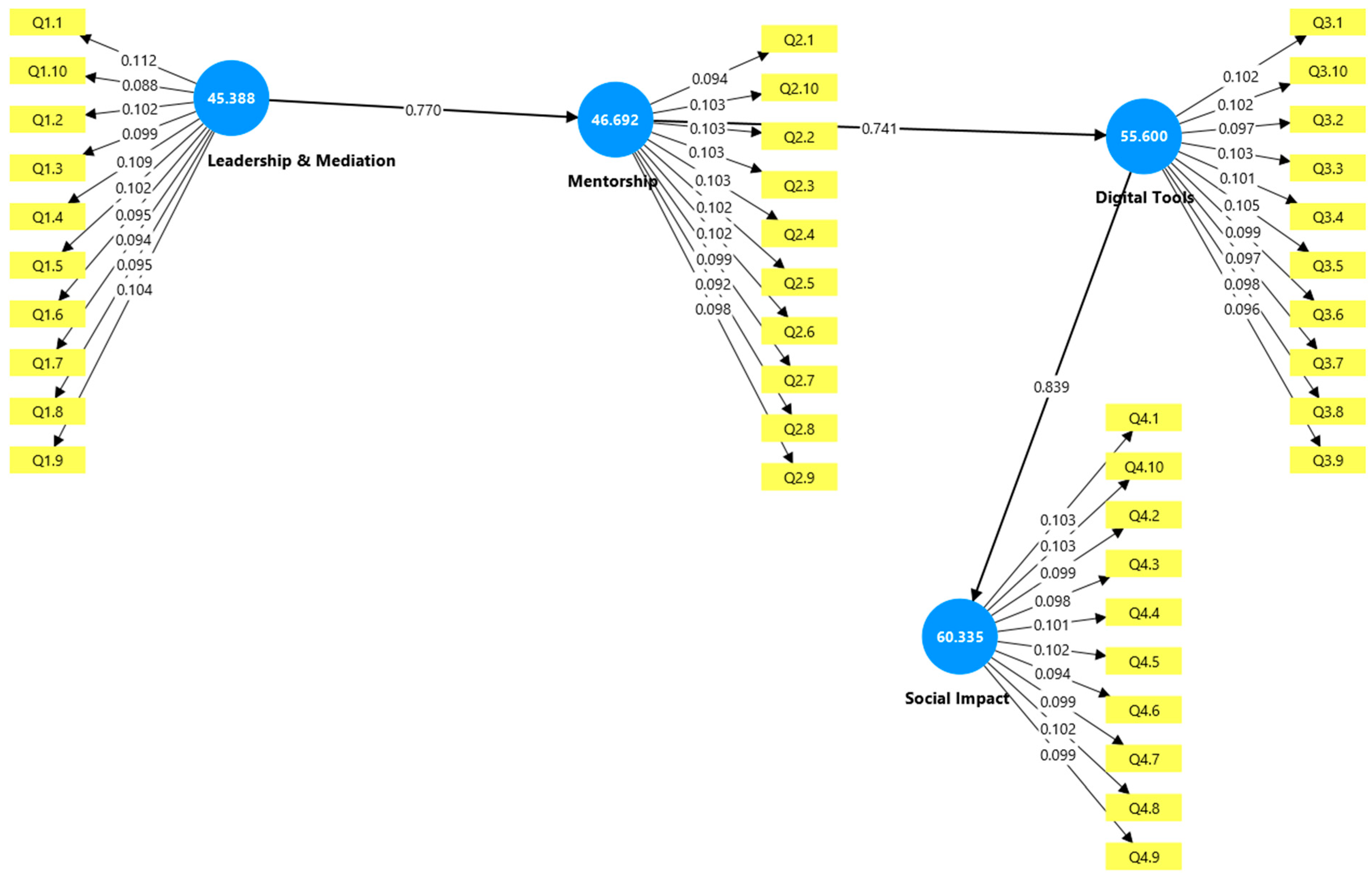

In order to enhance the analysis of the model’s results, an Importance-Performance Map Analysis (IPMA) was conducted focusing on the variable Social Impact. This method, as described by

Hair et al. (

2022), allows the simultaneous evaluation of the “importance” of each independent variable—that is, its overall effect on Social Impact—and its “performance”, which reflects the average achievement level of each construct in the sample (

Hair et al., 2022).

The IPMA results indicate that the use of Digital Tools has the greatest importance for increasing Social Impact, with a total effect (importance) of 0.839 and a performance level of 55.600 (

Figure 3). This practically means that any improvement in the dimension of digital tools has the potential to cause the most substantial and immediate increase in social cohesion compared to the other dimensions. This finding is particularly important as it implies that training programs, investments in technological infrastructure, and interventions aimed at strengthening staff digital skills should become strategic priorities for public organizations and social support structures (

Bertot et al., 2012;

Van Dijk, 2021).

The mentorship dimension also has a significant contribution (importance = 0.741), but its average performance in the sample is lower (performance = 46.692). This means that while improvements in mentoring functions and processes have the potential to enhance social impact, the relative utilization of this variable in the sample remains limited. Therefore, strengthening mentoring programs—either through structured support groups or institutional actions for the development of guidance networks—could represent an additional effective strategic intervention, especially when combined with the enhancement of digital collaboration and training tools (

Brooman & Darwent, 2014).

Similarly, Leadership and Mediation shows an importance of 0.770 and a performance of 45.388. The analysis indicates that despite its steady contribution to enhancing social cohesion, its performance level remains relatively low in this specific organizational context. This suggests the need for further development of leadership skills, mediation culture, and conflict management training among employees and executives. Literature confirms that organizations developing a culture of participative leadership and contemporary mediation skills demonstrate improved outcomes in social inclusion and cohesion (

Allen et al., 2004;

Karakas & Sarigollu, 2013).

The final level of Social Impact in the sample is 60.335. This value, combined with the detailed importance and performance estimates for each independent variable, allows for practical conclusions: prioritizing actions to strengthen digital skills alongside investments in mentoring and leadership development constitute the two main pillars for improving social cohesion in multicultural and dynamic public sector work environments.

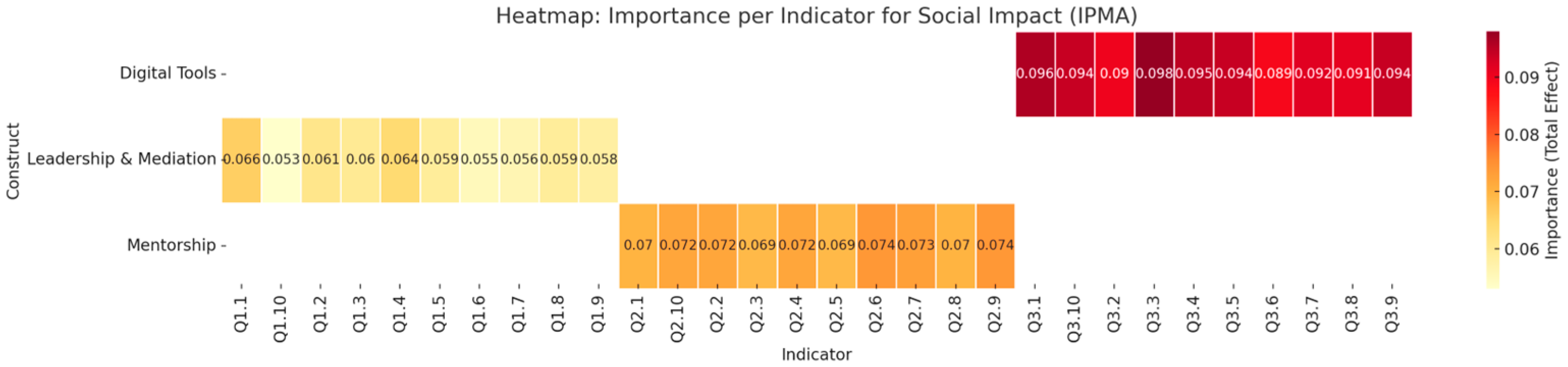

The results analysis is further deepened by mapping the importance of each individual indicator on the final outcome of social impact, using a heatmap visualization created with Python (version 3.9), employing the matplotlib library (version 3.7) and pandas (version 1.5). The graphical depiction of the heatmap reveals distinct differences among the three main axes of the model: Leadership and Mediation, mentorship, and Digital Tools. In particular, most indicators related to Digital Tools show the highest importance values, highlighting their weight in enhancing social cohesion. The intensity of the color shades in the heatmap confirms that indicators Q3.1, Q3.3, Q3.4, and Q3.10 contribute most significantly to the overall social impact.

On the mentorship axis, indicators present moderate importance values, without any single item standing out as a critical catalyst compared to the others. Although several mentorship indicators show noteworthy influence (e.g., Q2.6, Q2.9), no question exceeds the highest level of importance observed in digital tools. This finding suggests that mentorship functions more as a complementary mechanism enhancing social impact, especially when combined with strengthening digital skills.

Conversely, indicators related to Leadership and Mediation register significantly lower importance values, with most clustering near the lower threshold of the heatmap. This indicates that while leadership and mediation structures remain important at a theoretical level, their direct practical impact on social cohesion is limited compared to the other two dimensions. This result is also interpreted in international literature, where it is argued that the successful implementation of leadership and mediation practices largely depends on their integration within digital environments and networked collaborations (

Bertot et al., 2012;

Hair et al., 2022).

In summary, the IPMA heatmap (

Figure 4) clearly demonstrates the dominance of digital tools as the main driver for improving social impact. The results indicate that targeted interventions to strengthen digital skills—especially those specific elements identified as highly important—have the potential to yield maximal benefits for the cohesion and functioning of the organization. These conclusions fully align with recent research findings, according to which technological empowerment and innovation constitute key pillars of social change (

Brooman & Darwent, 2014;

Van Dijk, 2021).

In conclusion, the comprehensive analyses presented in this section provide robust evidence supporting the structural relationships and predictive capabilities of the proposed model. The integration of direct, indirect, and importance-performance evaluations offers a thorough understanding of the factors influencing social impact. These results contribute valuable insights for both theory and practice, particularly in the context of enhancing social cohesion through leadership, mentorship, and digital tools.