Driving Innovative Work Behavior Among University Teachers Through Work Engagement and Perceived Organizational Support

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Can ethical leadership predict innovative work behavior among university students in Turkey?

- (2)

- Does work engagement mediate this relationship? And

- (3)

- Does perceived organizational support moderate this relationship?

2. Hypotheses and Theories

2.1. Theoretical Framework

2.2. Ethical Leadership and Innovative Work Behavior

2.3. Mediating Influence of Work Engagement

2.4. Moderating Impact of Perceived Organizational Support

3. Research Design

3.1. Methodology and Approach

3.2. Participants’ Information

3.3. Measurements

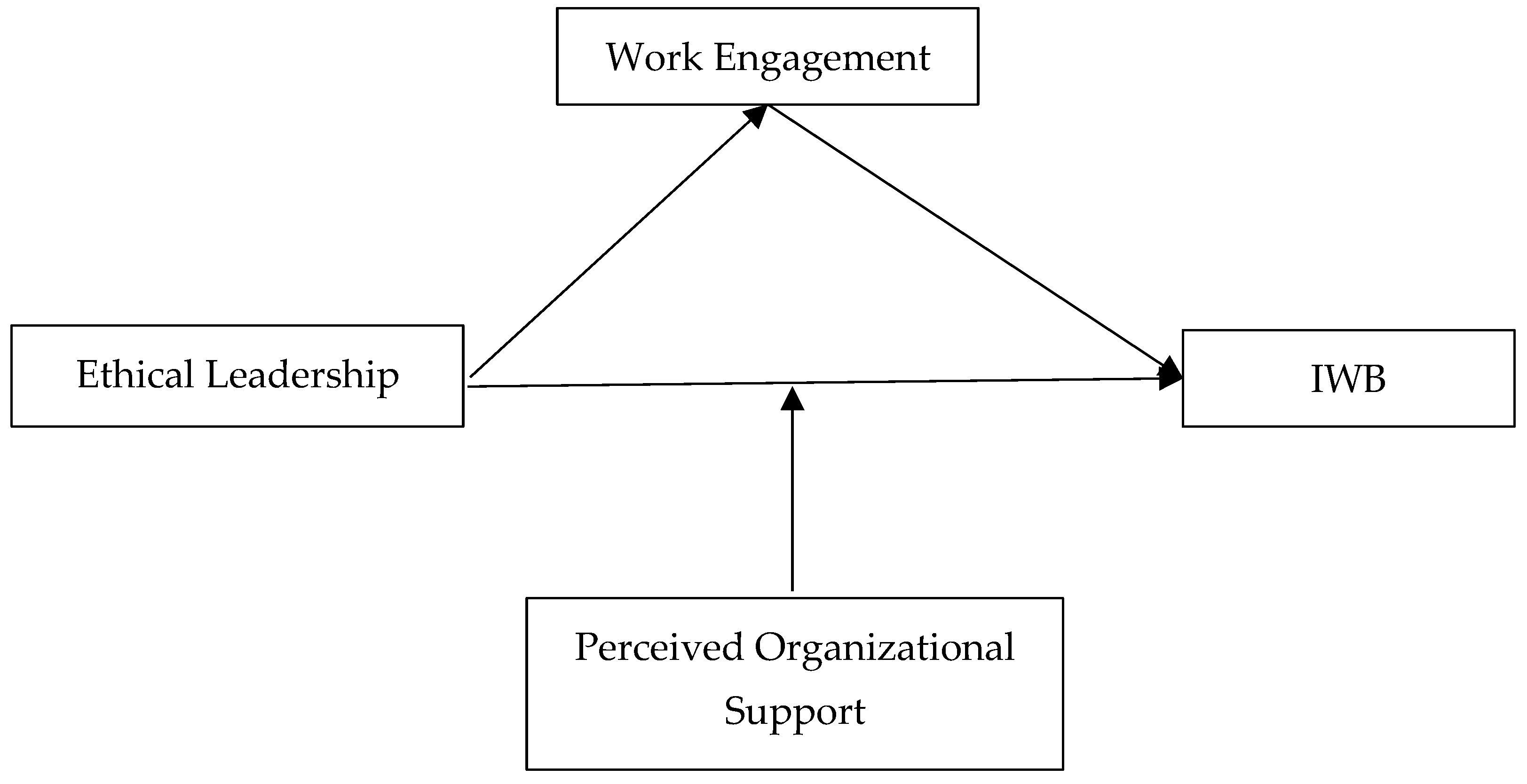

3.4. Research Model

4. Analysis and Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Theoretical Implications

7. Practical Implications

8. Limitations and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire

| Construct | Dimension | Item | Question |

| Ethical Leadership | Fairness | EL1 | My supervisor treats everyone fairly. |

| EL2 | My supervisor makes fair and balanced decisions. | ||

| EL3 | My supervisor avoids favoritism. | ||

| Power Sharing | EL4 | My supervisor encourages employees to voice their opinions. | |

| EL5 | My supervisor consults employees when making decisions. | ||

| EL6 | My supervisor allows subordinates to influence critical decisions. | ||

| Role Clarification | EL7 | My supervisor communicates expectations clearly. | |

| EL8 | My supervisor explains how job roles contribute to the overall goals. | ||

| EL9 | My supervisor provides guidance on how to perform tasks. | ||

| People Orientation | EL10 | My supervisor shows concern for others’ needs and wellbeing. | |

| EL11 | My supervisor helps subordinates with personal problems. | ||

| EL12 | My supervisor supports employee development. | ||

| Integrity | EL13 | My supervisor acts consistently with the values he/she promotes. | |

| EL14 | My supervisor keeps his/her promises. | ||

| EL15 | My supervisor is honest and trustworthy. | ||

| Ethical Guidance | EL16 | My supervisor sets a good example of ethical behavior. | |

| EL17 | My supervisor explains the ethical rules and principles. | ||

| EL18 | My supervisor defines success not just by results but also by the way they are obtained. | ||

| Work Engagement | Vigor | WE1 | I feel full of energy at my job. |

| WE2 | At my work, I feel strong and vigorous. | ||

| WE3 | I can continue working for long periods of time without getting tired. | ||

| Dedication | WE4 | I am enthusiastic about my job. | |

| WE5 | My job inspires me. | ||

| WE6 | I am proud of the work that I do. | ||

| Absorption | WE7 | I get carried away when I’m working. | |

| WE8 | Time flies when I’m working. | ||

| WE9 | I am immersed in my work. | ||

| Innovative Work Behavior | Idea Generation | IWB1 | I generate original solutions for problems at work. |

| IWB2 | I come up with new ideas to improve performance. | ||

| IWB3 | I regularly suggest new approaches to tasks. | ||

| Idea Promotion | IWB4 | I attempt to gain support for innovative ideas. | |

| IWB5 | I promote new ideas to colleagues. | ||

| IWB6 | I try to convince others of the value of new ideas. | ||

| Idea Realization | IWB7 | I transform innovative ideas into practical applications. | |

| IWB8 | I make efforts to implement new ideas at work. | ||

| IWB9 | I contribute to turning creative ideas into useful outcomes. | ||

| Perceived Organizational Support | - | POS1 | My organization values my contributions. |

| POS2 | My organization cares about my wellbeing. | ||

| POS3 | My organization supports me when I have a problem. | ||

| POS4 | My organization appreciates extra effort from me. | ||

| POS5 | My organization would forgive an honest mistake. |

References

- Ahmad, I., Gao, Y., Su, F., & Khan, M. K. (2023). Linking ethical leadership to followers’ innovative work behavior in Pakistan: The vital roles of psychological safety and proactive personality. European Journal of Innovation Management, 26(3), 755–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S., Fazal-E-Hasan, S. M., & Kaleem, A. (2018). How ethical leadership stimulates academics’ retention in universities: The mediating role of job-related affective well-being. International Journal of Educational Management, 32(7), 1348–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S., Sohal, A. S., & Wolfram Cox, J. (2020). Leading well is not enough: A new insight from the ethical leadership, workplace bullying and employee well-being relationships. European Business Review, 32(2), 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed Iqbal, Z., Abid, G., Contreras, F., Hassan, Q., & Zafar, R. (2020). Ethical leadership and innovative work behavior: The mediating role of individual attributes. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 6(3), 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akcil, U., & Suhanberdyyeva, D. (2022). Research on university profiles about entrepreneurship and innovation orientation: Case of a developing country. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 968996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Husseini, S., & Elbeltagi, I. (2016). Transformational leadership and innovation: A comparison study between Iraq’s public and private higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 41(1), 159–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, F., Abid, G., & Ilyas, S. (2021). Impact of ethical leadership on employee engagement: Role of self-efficacy and organizational commitment. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 11(3), 962–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkar, B. (2024). The relationships between organizational climate, innovative behavior and job performance of teachers. International Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 7(2), 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernerth, J. B., Cole, M. S., Taylor, E. C., & Walker, H. J. (2018). Control variables in leadership research: A qualitative and quantitative review. Journal of Management, 44(1), 131–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cann, R. F., Riedel-Prabhakar, R., & Powell, D. (2021). A model of positive school leadership to improve teacher wellbeing. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology, 6(2), 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. C., Liu, T. Y., & Chen, H. C. (2024). Relationship between transformational leadership, work engagement, and organisational citizenship behaviour: The moderating effect of work engagement. Educational Studies, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W. S., Kang, S. W., & Choi, S. B. (2021). Innovative behavior in the workplace: An empirical study of moderated mediation model of self-efficacy, perceived organizational support, and leader–member exchange. Behavioral Sciences, 11(12), 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, J., & Ayoko, O. B. (2021). Employees’ self-determined motivation, transformational leadership and work engagement. Journal of Management & Organization, 27(3), 523–543. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum. [Google Scholar]

- De Hoogh, A. H., & Den Hartog, D. N. (2008). Ethical and despotic leadership, relationships with leader’s social responsibility, top management team effectiveness and subordinates’ optimism: A multi-method study. The Leadership Quarterly, 19(3), 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, J., & Den Hartog, D. (2010). Measuring innovative work behaviour. Creativity and Innovation Management, 19(1), 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A., Sarstedt, M., Fuchs, C., Wilczynski, P., & Kaiser, S. (2012). Guidelines for choosing between multi-item and single-item scales for construct measurement: A predictive validity perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 434–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T. K., & Henseler, J. (2015). Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Quarterly, 39(2), 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R., Malone, G. P., & Presson, W. D. (2016). Optimizing perceived organizational support to enhance employee engagement. Society for Human Resource Management and Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 2, 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ekmekcioglu, E. B., & Öner, K. (2024). Servant leadership, innovative work behavior and innovative organizational culture: The mediating role of perceived organizational support. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 33(3), 272–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersozlu, A., Karakus, M., Karakas, F., & Clouder, D. L. (2024). Nurturing a climate of innovation in a didactic educational system: A case study exploring leadership in private schools in Turkey. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 23(2), 275–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eva, N., Newman, A., Miao, Q., Wang, D., & Cooper, B. (2020). Antecedents of duty orientation and follower work behavior: The interactive effects of perceived organizational support and ethical leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 161, 627–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, M., Meng, F., Raza, A., & Wu, Y. (2022). Innovative work behaviour: The what, where, who, how and when. Personnel Review, 52(1), 74–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallos, J. V., & Bolman, L. G. (2021). Reframing academic leadership. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Gudergan, S. P. (2017). Advanced issues in partial least squares structural equation modeling. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, R. S., Amin, H. M., & Ghoneim, H. (2024). Decent work and innovative work behavior of academic staff in higher education institutions: The mediating role of work engagement and job self-efficacy. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Dijkstra, T. K., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., Diamantopoulos, A., Straub, D. W., Ketchen, D. J., Jr., Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., & Calantone, R. J. (2014). Common beliefs and reality about PLS: Comments on Rönkkö and Evermann (2013). Organizational Research Methods, 17(2), 182–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based struc-tural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New challenges to international marketing. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Hoang, G., Luu, T. T., Du, T., & Nguyen, T. T. (2023). Can both entrepreneurial and ethical leadership shape employees’ service innovative behavior? Journal of Services Marketing, 37(4), 446–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horoub, I., & Zargar, P. (2022). Empowering leadership and job satisfaction of academic staff in Palestinian universities: Implications of leader-member exchange and trust in leader. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1065545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S., & Haghighi Shirazi, Z. R. (2021). Towards teacher innovative work behavior: A conceptual model. Cogent Education, 8(1), 1869364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R. T. (2025). Exploring the roles of self-determined motivation and perceived organizational support in organizational change. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 34(2), 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T., Zulfiqar, I., Aftab, H., Alkharabsheh, O. H. M., & Shahid, M. K. (2024). Testing the waters! The role of ethical leadership towards innovative work behavior through psychosocial well-being and perceived organizational support. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 37(5), 1051–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işık, C., Aydın, E., Dogru, T., Rehman, A., Alvarado, R., Ahmad, M., & Irfan, M. (2021). The nexus between team culture, innovative work behaviour and tacit knowledge sharing: Theory and evidence. Sustainability, 13(8), 4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, O. (2000). Job demands, perceptions of effort-reward fairness and innovative work behaviour. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 73(3), 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehanzeb, K., & Mushtaq, M. (2025). Examining the impact of well-being-oriented HRM practices on innovative work behavior: The moderating role of servant leadership. Cogent Business & Management, 12(1), 2482015. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, K., Zhu, T., Zhang, W., Rasool, S. F., Asghar, A., & Chin, T. (2022). The linkage between ethical leadership, well-being, work engagement, and innovative work behavior: The empirical evidence from the higher education sector of China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johari, A., Abdul Wahat, N. W., & Zaremohzzabieh, Z. (2021). Innovative work behavior among teachers in Malaysia: The effects of teamwork, principal support, and humor. Asian Journal of University Education (AJUE), 7(2), 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K. G. (1971). Simultaneous factor analysis in several populations. Psychometrika, 36(4), 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Huang, Y., Kim, J., & Na, S. (2023). How ethical leadership cultivates innovative work behaviors in employees? Psychological safety, work engagement and openness to experience. Sustainability, 15(4), 3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messmann, G., & Mulder, R. H. (2015). Reflection as a facilitator of teachers’ innovative work behaviour. International Journal of Training and Development, 19(2), 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musenze, I. A., & Mayende, T. S. (2023). Ethical leadership (EL) and innovative work behavior (IWB) in public universities: Examining the moderating role of perceived organizational support (POS). Management Research Review, 46(5), 682–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozbilgin, M. F. (2011). 11. Leadership in Turkey: Toward an evidence based and contextual approach1. Leadership Development in the Middle East, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., Podsakoff, N. P., Williams, L. J., Huang, C., & Yang, J. (2024). Common method bias: It’s bad, it’s complex, it’s widespread, and it’s not easy to fix. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 11(1), 17–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmat, A. (2022). Ethical leadership and innovative behaviour: Mediation role of leader member exchange and perceived organizational support. Jurnal Manajemen dan Bisnis, 11(1), 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajashekar, S., & Jain, A. (2024). A thematic analysis on “employee engagement in IT companies from the perspective of holistic well-being initiatives”. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 36(2), 165–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, S. F., Wang, M., Tang, M., Saeed, A., & Iqbal, J. (2021). How toxic workplace environment effects the employee engagement: The mediating role of organizational support and employee wellbeing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of applied psychology, 87(4), 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, H., Ishaq, M. I., Amin, A., & Ahmed, R. (2020). Ethical leadership, work engagement, employees’ well-being, and performance: A cross-cultural comparison. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(12), 2008–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(4), 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafait, Z., & Huang, J. (2023). Exploring the nexus of emotional intelligence and university performance: An investigation through perceived organizational support and innovative work behavior. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 16, 4295–4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanock, L. R., & Eisenberger, R. (2006). When supervisors feel supported: Relationships with subordinates’ perceived supervisor support, perceived organizational support, and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(3), 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, D., & Bhandari, D. (2024). Ethical leadership and employees’ innovative behavior: Exploring the mediating role of organizational support. The International Research Journal of Management Science, 9(1), 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H. Y. (2024). How does ethical leadership lead to work active employees? The perspective of self-determination theory. Current Psychology, 43(16), 14668–14675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uppathampracha, R., & Liu, G. (2022). Leading for innovation: Self-efficacy and work engagement as sequential mediation relating ethical leadership and innovative work behavior. Behavioral Sciences, 12(8), 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z., & Xu, H. (2019). When and for whom ethical leadership is more effective in eliciting work meaningfulness and positive attitudes: The moderating roles of core self-evaluation and perceived organizational support. Journal of Business Ethics, 156, 919–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeap, S. B. (2024). Did ethical leadership help to increase academic staff’s innovative work behavior? The mediating role of intrinsic motivation and proactive personality. Current Psychology, 43(11), 9625–9637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, K., Abid, G., Butt, T. H., Ilyas, S., & Ahmed, S. (2019). Impact of ethical leadership and thriving at work on psychological well-being of employees: Mediating role of voice behaviour. Business, Management and Economics Engineering, 17(2), 194–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagenczyk, T. J., Purvis, R. L., Cruz, K. S., Thoroughgood, C. N., & Sawyer, K. B. (2021). Context and social exchange: Perceived ethical climate strengthens the relationships between perceived organizational support and organizational identification and commitment. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(22), 4752–4771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G., Luan, Y., Ding, H., & Zhou, Z. (2022). Job control and employee innovative behavior: A moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 720654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Age | Frequency | Percentage |

| Below 28 | 7 | 3.2% |

| 28–34 | 63 | 28.5% |

| 35–40 | 84 | 38% |

| +40 | 67 | 30.3% |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 115 | 52.04 |

| Female | 106 | 47.96 |

| Work Experience | ||

| <3 years | 76 | 34.39% |

| 3–6 years | 98 | 44.34% |

| >6 years | 47 | 21.27% |

| Factors | Dimensions | Indicators | Outer Loadings | Alpha | Rho A | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethical Leadership | Fairness | EL1 | 0.751 | 0.781 | 0.768 | 0.781 | 0.612 |

| EL2 | 0.754 | ||||||

| EL3 | 0.762 | ||||||

| Power Sharing | EL4 | 0.734 | 0.763 | 0.757 | 0.802 | 0.603 | |

| EL5 | 0.748 | ||||||

| EL6 | 0.743 | ||||||

| Role Clarification | EL7 | 0.698 | 0.703 | 0.832 | 0.766 | 0.702 | |

| EL8 | 0.711 | ||||||

| EL9 | 0.725 | ||||||

| People Orientation | EL10 | 0.731 | 0.722 | 0.811 | 0.749 | 0.684 | |

| EL11 | 0.718 | ||||||

| EL12 | 0.733 | ||||||

| Integrity | EL13 | 0.749 | 0.745 | 0.809 | 0.732 | 0.705 | |

| EL14 | 0.751 | ||||||

| EL15 | 0.755 | ||||||

| Ethical Guidance | EL16 | 0.759 | 0.739 | 0.795 | 0.744 | 0.649 | |

| EL17 | 0.743 | ||||||

| EL18 | 0.764 | ||||||

| Innovative Work Behavior | Idea Generation | IWB1 | 0.811 | 0.774 | 0.802 | 0.768 | 0.581 |

| IWB2 | 0.785 | ||||||

| IWB3 | 0.752 | ||||||

| Idea Promotion | IWB4 | 0.759 | 0.782 | 0.804 | 0.773 | 0.592 | |

| IWB5 | 0.779 | ||||||

| IWB6 | 0.784 | ||||||

| Idea Realization | IWB7 | 0.764 | 0.764 | 0.794 | 0.748 | 0.613 | |

| IWB8 | 0.766 | ||||||

| IWB9 | 0.759 | ||||||

| Perceived Organizational Support | - | POS1 | 0.812 | 0.786 | 0.811 | 0.788 | 0.596 |

| POS2 | 0.733 | ||||||

| POS3 | 0.783 | ||||||

| POS4 | 0.776 | ||||||

| POS5 | 0.739 | ||||||

| Work Engagement | Vigor | WE1 | 0.811 | 0.801 | 0.827 | 0.759 | 0.588 |

| WE2 | 0.809 | ||||||

| WE3 | 0.807 | ||||||

| Dedication | WE4 | 0.781 | 0.743 | 0.816 | 0.766 | 0.605 | |

| WE5 | 0.804 | ||||||

| WE6 | 0.792 | ||||||

| Absorption | WE7 | 0.859 | 0.794 | 0.733 | 0.701 | 0.667 | |

| WE8 | 0.863 | ||||||

| WE9 | 0.721 |

| FR | PS | RC | PO | IN | EG | VG | DD | AP | IG | IP | IR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FR | - | |||||||||||

| PS | 0.701 | - | ||||||||||

| RC | 0.445 | 0.523 | - | |||||||||

| PO | 0.732 | 0.614 | 0.701 | - | ||||||||

| IN | 0.613 | 0.654 | 0.644 | 0.671 | - | |||||||

| EG | 0.614 | 0.622 | 0.651 | 0.677 | 0.715 | - | ||||||

| VG | 0.611 | 0.595 | 0.640 | 0.613 | 0.643 | 0.676 | - | |||||

| DD | 0.511 | 0.526 | 0.579 | 0.586 | 0.578 | 0.603 | 0.713 | - | ||||

| AP | 0.603 | 0.621 | 0.629 | 0.597 | 0.590 | 0.613 | 0.644 | 0.659 | - | |||

| IG | 0.669 | 0.611 | 0.549 | 0.579 | 0.620 | 0.633 | 0.679 | 0.608 | 0.701 | - | ||

| IP | 0.612 | 0.634 | 0.598 | 0.574 | 0.560 | 0.577 | 0.519 | 0.583 | 0.589 | 0.684 | - | |

| IR | 0.675 | 0.591 | 0.618 | 0.674 | 0.639 | 0.619 | 0.594 | 0.649 | 0.677 | 0.681 | 0.731 | - |

| POS | 0.644 | 0.613 | 0.715 | 0.648 | 0.679 | 0.619 | 0.685 | 0.688 | 0.701 | 0.689 | 0.688 | 0.742 |

| Construct | Items | Convergent Validity | Weights | VIF | t-Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethical Leadership | FR | 0.713 | 0.352 | 1.819 | 4.001 |

| PS | 0.356 | 1.745 | 4.011 | ||

| RC | 0.361 | 1.746 | 3.878 | ||

| PO | 0.349 | 1.846 | 3.944 | ||

| IN | 0.353 | 1.711 | 3.988 | ||

| EG | 0.357 | 1.766 | 4.044 | ||

| IWB | IG | 0.708 | 0.323 | 1.776 | 4.019 |

| IP | 0.319 | 1.713 | 3.849 | ||

| IR | 0.330 | 1.702 | 3.977 | ||

| Work Engagement | VG | 0.703 | 0.349 | 1.639 | 4.012 |

| DD | 0.344 | 1.644 | 3.833 | ||

| AP | 0.338 | 1.619 | 3.849 |

| Effects | Relations | β | t-Statistics | Ƒ2 | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | |||||

| H1 | EL → IWB | 0.344 | 4.244 ** | 0.103 | Supported |

| Mediation | |||||

| H2 | EL → WE → IWB | 0.314 | 2.531 * | 0.107 | Supported |

| Moderation | |||||

| EL * POS → IWB | 0.323 | 2.679 * | 0.110 | Supported | |

| Control Variables | |||||

| Gender → IWB | 0.112 | 2.302 * | |||

| Age → IWB | 0.104 | 2.250 * | |||

| Experience → IWB | 0.109 | 2.264 * | |||

| R2WE = 0.32/Q2WE = 0.14 R2IWB = 0.43/Q2IWB = 0.24 SRMR: 0.023; NFI: 0.922 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zargar, P.; Daouk, A.; Chahine, S. Driving Innovative Work Behavior Among University Teachers Through Work Engagement and Perceived Organizational Support. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15070246

Zargar P, Daouk A, Chahine S. Driving Innovative Work Behavior Among University Teachers Through Work Engagement and Perceived Organizational Support. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(7):246. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15070246

Chicago/Turabian StyleZargar, Pouya, Amira Daouk, and Sarah Chahine. 2025. "Driving Innovative Work Behavior Among University Teachers Through Work Engagement and Perceived Organizational Support" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 7: 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15070246

APA StyleZargar, P., Daouk, A., & Chahine, S. (2025). Driving Innovative Work Behavior Among University Teachers Through Work Engagement and Perceived Organizational Support. Administrative Sciences, 15(7), 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15070246