Can Public Housing Truly Be Innovative? Lessons from Vienna to Reimagine the Future of Local Governance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Historical Context

2.2. The Vienna Model

- A Comprehensive Legal and Regulatory Framework: At its core is the General Tenancy Law (Mietrechtsgesetz, MRG), which establishes critical protections such as rent ceilings, defines tenant and landlord rights and obligations, and safeguards against arbitrary eviction.

- Centralised Public Administration and Management: The municipal agency, Wiener Wohnen, plays a pivotal role in administering the extensive municipal housing stock (Gemeindebauten) and enforcing cohabitation regulations detailed in the Hausordnung (house rules) (Magistrat der Stadt Wien—Wiener Wohnen, 2024b).

- Dual Financial Subsidy System: A distinctive feature is the dual subsidy model, where public funds support both the supply side (financing new construction and renovations) and the demand side (providing direct assistance to low-income tenants) (Magistrat der Stadt Wien—Wiener Wohnen, 2024d, 2024e). This is complemented by regulated operating costs (Betriebskosten) for tenants.

- Integral Role of Non-Profit Housing Associations: Limited-profit housing associations (Bauträger<), organised under bodies like the Österreichischer Verband gemeinnütziger Bauvereinigungen (2016), function as crucial partners in developing and managing a significant portion of Vienna’s regulated rental housing, historically complementing direct municipal provision and adhering to strict quality and affordability criteria.

- Socially Oriented Allocation and Tenancy Support: The model incorporates specific criteria for housing allocation alongside robust support mechanisms, such as advisory services and assistance for tenants in rent arrears (Magistrat der Stadt Wien—Wiener Wohnen, 2024a), aimed at ensuring residential stability and preventing eviction.

- These core mechanisms function within a dynamic environment shaped by significant influencing factors, including persistent financialization pressures, the challenge of rising land values, and the evolving demographic needs of a diverse population, including migrants and refugees. The following detailed analysis will further elaborate on these elements and integrate critical perspectives from the academic literature.

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results: Lights and Shadows of Vienna’s Housing Paradigm

5. Discussion

5.1. Empirical Insights: Navigating Achievements and Contradictions

5.2. Conceptual Reassessment and Normative Implications

6. Conclusions

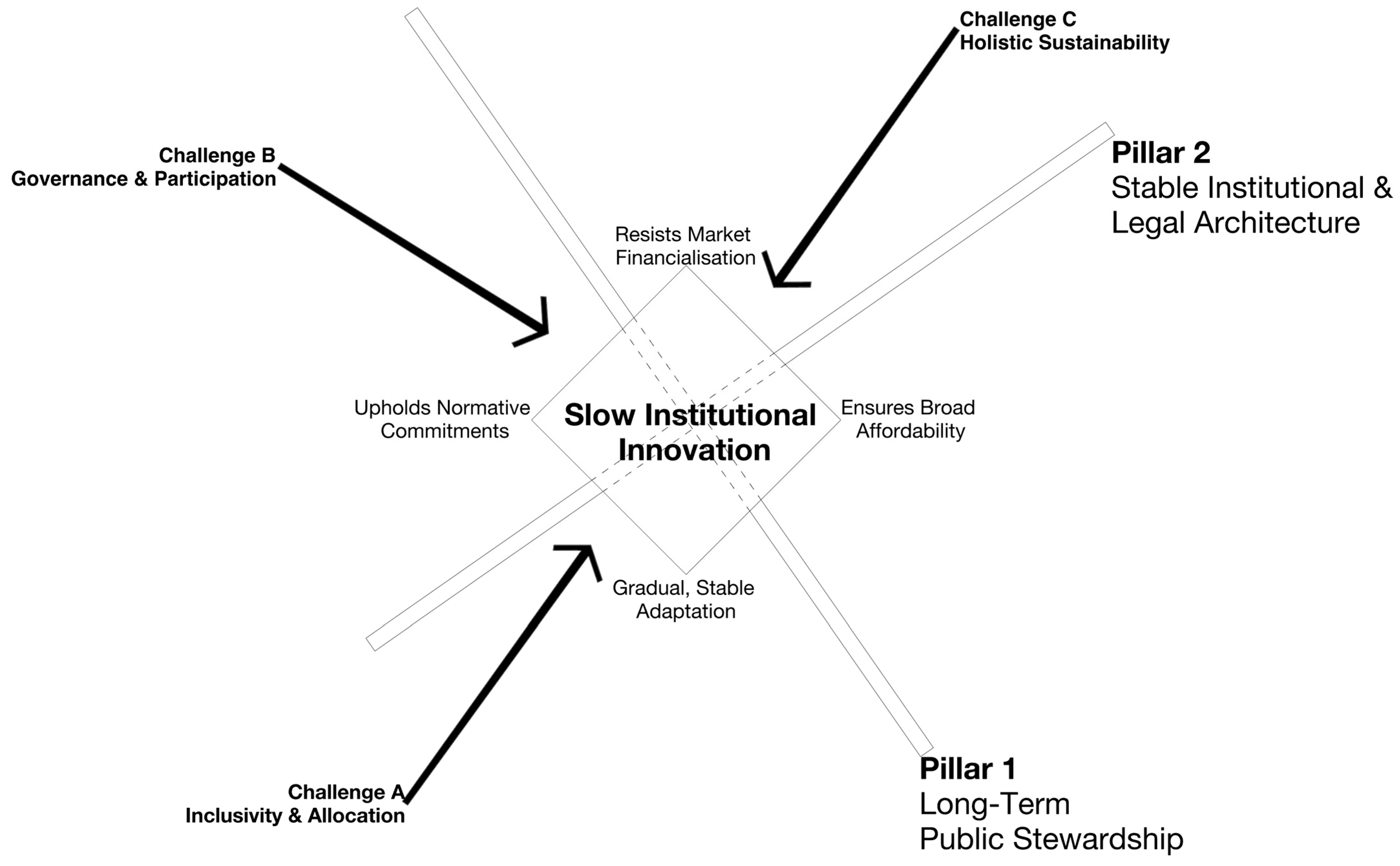

- Prioritise Long-Term Institutional Stability and Public Stewardship: Municipalities should focus on building and maintaining robust public or socially controlled land banks, implementing effective rent regulation mechanisms, and ensuring sustained, ring-fenced public investment in both the construction of new affordable units and the comprehensive maintenance and ecological retrofitting of existing stock. This requires a long-term vision that moves beyond short-term, market-led solutions.

- Develop Integrated and Genuinely Inclusive Allocation Systems: While preserving the benefits of broad eligibility, housing authorities must proactively design and implement targeted strategies to counteract the exclusion of highly vulnerable populations (e.g., newly arrived refugees, individuals in extreme poverty, those with precarious legal status). This could involve enhancing inter-agency collaboration, simplifying access procedures, and providing dedicated support services.

- Embed Genuine Community Participation and Foster Co-Production: To move beyond superficial consultation, policymakers should create structural opportunities for meaningful tenant involvement in the governance and management of their housing. Furthermore, enabling legal and financial frameworks are needed to support the growth and integration of alternative tenure and management models, such as co-housing and community land trusts, allowing them to scale beyond niche experiments.

- Champion Deep Environmental and Social Sustainability Holistically: Urban housing policy must comprehensively integrate ecological and social goals. This means prioritising the deep ecological renovation of existing buildings alongside sustainable new construction, and strategically designing housing environments that actively foster social interaction, mutual support, and a tangible sense of community, rather than merely aiming for a demographic mix.

| Key Area | Policy Recommendations | Future Research Directions |

|---|---|---|

| Institutional Stability & Stewardship | Prioritise long-term public control of land, implement effective rent regulation, and ensure sustained public investment in new construction and maintenance/retrofitting of existing stock. | Conduct comparative institutional analyses between Vienna and other cities to identify the conditions that enable or constrain “slow innovation” in different contexts. |

| Inclusivity & Allocation | Develop targeted strategies to counteract exclusion by enhancing inter-agency collaboration, simplifying access, and providing dedicated support services. | Conduct ethnographic research to explore the lived realities of residents, how they navigate governance, and how inclusion efforts are perceived on the ground. |

| Governance & Participation | Create structural opportunities for meaningful tenant involvement in governance. Establish legal and financial frameworks to help alternative tenure models (e.g., co-housing) scale beyond niche experiments. | Investigate the barriers and enablers to scaling up grassroots housing innovations within larger, more bureaucratic systems. |

| Sustainability | Prioritise deep ecological renovation of existing buildings and design housing environments that actively foster social interaction and a tangible sense of community. | Explore how sustainability and community-building efforts are enacted and experienced at the ground level through fine-grained ethnographic studies. |

- Comparative Institutional Analyses of “Slow Innovation”: Future research could conduct in-depth, qualitative comparative studies between Vienna and other cities (e.g., Helsinki, as explored by Kadi & Lilius, or cities with more residual housing systems) to identify the specific institutional configurations, political conditions, and policy levers that enable or constrain the development and resilience of “slow innovation” in diverse socio-economic contexts.

- Ethnographic Exploration of Governance and Lived Realities: There is a need for fine-grained ethnographic research within various Viennese public, cooperative, and co-housing settings. Such studies could investigate how residents experience and negotiate governance structures, how social interactions are shaped by design and management, and how efforts towards inclusion, sustainability, and participation are perceived and enacted at the ground level.

- Investigating Mechanisms for Scaling and Adapting Innovations: Future studies should critically examine the barriers and enablers to scaling up successful grassroots housing innovations (like Baugruppen or habiTAT projects) within larger, more bureaucratized housing systems. This includes exploring how core principles of the Viennese model (e.g., public land control, dual subsidy systems) might be adapted in cities with different political economies and resource constraints.

- Developing Frameworks for Evaluating “Slow Institutional Innovation”: Research is needed to develop robust analytical frameworks and metrics specifically designed to assess the multifaceted impacts of “slow institutional innovation.” These should capture not only quantitative outputs but also qualitative dimensions such as institutional resilience, democratic legitimacy, long-term social equity, and the capacity for adaptive learning within public organisations.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aalbers, M. B. (2012). Subprime cities: The political economy of mortgage markets. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-3776-1. [Google Scholar]

- Adetola, A. A., Courage, I., Azubuike, C. O., & Obinna, I. (2024). Economic and social impact of affordable housing policies: A comparative review. International Journal of Applied Research in Social Sciences, 6, 1433–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aigner, A. (2019). Housing entry pathways of refugees in Vienna, a city of social housing. Housing Studies, 34(5), 779–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aigner, A. (2022). What’s wrong with investment apartments? On the construction of a ‘financialized’ rental investment product in Vienna. Housing Studies, 37(2), 355–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez de Andres, E., Cabrera, C., & Smith, H. (2019). Resistance as resilience: A comparative analysis of state-community conflicts around self-built housing in Spain, Senegal and Argentina. Habitat International, 86, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Loyola, M., & Vergara-Perucich, F. (2021). Co-producing the right to fail: Resilient grassroot cooperativism in a Chilean informal settlement. International Development Planning Review, 43(1), 33–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babos, A., Orbán, A., & Benkő, M. (2024). Innovative housing models to support shared use of space: The case study of Sonnwendviertel Ost in Vienna. City, Territory and Architecture, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banabak, S., Kadi, J., & Schneider, A. E. (2024). Gentrification and the suburbanization of poverty: Evidence from a highly regulated housing system. Urban Geography, 45(10), 1596–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, R. (2021). A thematic analysis to identify barriers, gaps, and challenges for the implementation of public-private-partnerships in housing. Habitat International, 118, 102454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. (2012). Social science research: Principles, methods, and practices. University of South Florida. ISBN 978-1-4751-4612-7. [Google Scholar]

- Boano, C., & Vergara-Perucich, J. F. (2016). Bajo escasez. ¿Media casa basta? Reflexiones sobre el Pritzker de Alejandro Aravena [Under scarcity. Is half a house enough? Reflections on Alejandro Aravena’s Pritzker]. Revista de Arquitectura, 21, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bonhomme, M. (2021). Racism in multicultural neighbourhoods in Chile: Housing precarity and coexistence in a migratory context. Bitácora Urbano Territorial, 31(1), 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, S., & O’Brien, D. (2021). Beyond the freedom to build: Long-term outcomes of Elemental’s incremental housing in Quinta Monroy. URBE: Revista Brasileira de Gestão Urbana, 13, e20200173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, Y., Neville, L., & Gonzalez, R. (2019). In-formality in access to housing for Latin American migrants: A case study of an intermediate Chilean city. International Journal of Housing Policy, 19(3), 411–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras Gatica, Y., & Seguel Calderón, B. (2023). Gentrificación e inmigración: Una relación frente a la crisis migratoria y habitacional chilena [Gentrification and immigration: A relationship in the face of the Chilean migratory and housing crisis]. Scripta Nova, 27, 41169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer-Greenbaum, S. (2021). Who can afford a ‘livable’ place? The part of living global rankings leave out. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, 13(1), 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W. (2007). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed method approaches (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economist Intelligence Unit. (2024). Global liveability index 2024. Available online: https://www.eiu.com/n/campaigns/global-liveability-index-2024/ (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Eder, J., Gruber, E., Görgl, P., & Hemetsberger, M. (2018). How Vienna grows: Monitoring of current trends of population and settlement dynamics in the Vienna urban region [Wie Wien wächst: Monitoring aktueller Trends hinsichtlich Bevölkerungs- und Siedlungsentwicklung in der Stadtregion Wien]. Raumforschung und Raumordnung, 76(4), 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eseonu, T. (2022). Co-creation as social innovation: Including ‘hard-to-reach’ groups in public service delivery. Public Money & Management, 42(4), 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essletzbichler, J., & Forcher, J. (2022). “Red Vienna” and the rise of the populist right. European Urban and Regional Studies, 29(2), 126–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira Costa, C. G. (2020). Disaster risk management as a process to forge climate-resilient pathways: Lessons learned from Cabo Verde. Desenvolvimento e Meio Ambiente, 53, 205–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, Y., & Gruber, E. (2018). Housing “for all” in times of the housing market crisis? The social housing construction in Vienna between claim and reality [Wohnen “für alle” in Zeiten der Wohnungsmarktkrise?: Der soziale Wohnungsbau in Wien zwischen Anspruch und Wirklichkeit]. Standort, 42, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frątczak-Müller, J. (2022). Innovative housing policy and (vulnerable) residents’ quality of life. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 751208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurran, N. (2003). Housing locally: Positioning Australian local government housing for a new century. Urban Policy and Research, 21(4), 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacke, U., Müller, K., & Dütschke, E. (2019). Cohousing—Social impacts and major implementation challenges. GAIA—Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society, 28(S1), 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölzl, C., Hölzl, D., & Amacher, D. (2022). Netzwerkstrategien von “Housing Commons” in der Gründungsphase—Das Beispiel der “habitat”-Hausprojekte “SchloR” und “Bikes and Rails” in Wien [Network strategies of “Housing Commons” in the founding phase—The example of the “habiTAT” housing projects “SchloR” and “Bikes and Rails” in Vienna]. Monatshefte für Ökonomie, Geschichte und Gesellschaftskritik, 1, 171–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P. (2017). Housing resilience and the informal city. Journal of Regional and City Planning, 28(2), 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadi, J. (2015). Recommodifying housing in formerly “Red” Vienna? Housing, Theory and Society, 32(3), 247–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadi, J., & Lilius, J. (2024). The remarkable stability of social housing in Vienna and Helsinki: A multi-dimensional analysis. Housing Studies, 39(7), 1607–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomenko, S., Nieuwenhuijsen, M., Ambròs, A., Wegener, S., & Mueller, N. (2020). Is a liveable city a healthy city? Health impacts of urban and transport planning in Vienna, Austria. Environmental Research, 183, 109238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraftl, P. (2007). Utopia, performativity, and the unhomely. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 25(1), 120–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magistrat der Stadt Wien—Wiener Wohnen. (2024a). Hilfe bei mietschulden. Magistrat der Stadt Wien. [Google Scholar]

- Magistrat der Stadt Wien—Wiener Wohnen. (2024b). Hausordnung. Magistrat der Stadt Wien. Available online: https://www.wien.gv.at/wohnen/wohnbautechnik/pruefen/betriebskostenrechner.html (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Magistrat der Stadt Wien—Wiener Wohnen. (2024c). Betriebskosten. Magistrat der Stadt Wien. [Google Scholar]

- Magistrat der Stadt Wien—Wiener Wohnen. (2024d). Municipal housing in Vienna: History, facts & figures. Magistrat der Stadt Wien. [Google Scholar]

- Magistrat der Stadt Wien—Wiener Wohnen. (2024e). Der wiener gemeindebau: Geschichte, daten, fakten. Magistrat der Stadt Wien. [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt, S., & Glaser, D. (2023). How much state and how much market? Comparing social housing in berlin and Vienna. In German politics (Vol. 32, Issue 2, pp. 361–380). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawetz, U. B., & Klaiber, H. A. (2022). Does housing policy impact income sorting near urban amenities? Evidence from Vienna, Austria. The Annals of Regional Science, 69(2), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morphet, J., & Clifford, B. (2021). Reviving local authority housing delivery: Challenging austerity through municipal entrepreneurialism. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Novy, A., Redak, V., Jäger, J., & Hamedinger, A. (2001). The end of Red Vienna: Recent ruptures and continuities in urban governance. European Urban and Regional Studies, 8(2), 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzau, B., & Trillo, C. (2020). Affordable housing provision in informal settlements through land value capture and inclusionary housing. Sustainability, 12(15), 5975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Österreichischer Verband gemeinnütziger Bauvereinigungen. (2016). 70 Jahre Österreichischer Verband gemeinnütziger Bauvereinigungen—Revisionsverband: Festschrift. MRG. [Google Scholar]

- Paidakaki, A., & Lang, R. (2021). Uncovering social sustainability in housing systems through the lens of institutional capital: A study of two housing alliances in Vienna, Austria. Sustainability, 13(17), 9726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, K. A. R., & Hemphill, M. A. (2018). A practical guide to collaborative qualitative data analysis. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 37(2), 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolnik, R. (2013). Late neoliberalism: The financialization of homeownership and housing rights. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(3), 1058–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, W., & Drenth, M. (2020). Local governance and access to urban services: Political and social inclusion in Indonesia. In S. Cheema (Ed.), Governance for urban services (pp. 153–183). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schikowitz, A., & Pohler, N. (2024). Varieties of alternativeness: Relational practices in collaborative housing in Vienna. The Sociological Review, 72(2), 301–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammaru, T., Marcińczak, S., van Ham, M., & Musterd, S. (Eds.). (2015). Socio-economic segregation in European capital cities: East meets West. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Unterdorfer, D. (2016). “I have no contact to other inhabitants...” Social mixing in a Viennese district—The dichotomy of a concept [“Ich habe keinen Kontakt zu anderen Bewohnern...” Soziale Durchmischung in einem Wiener Bezirk—Die Dichotomie eines Konzeptes]. Mitteilungen der Österreichischen Geographischen Gesellschaft, 158, 109–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara-Perucich, F. (2021). Participatory action planning as transductive reasoning: Towards the right to the city in Los Arenales, Antofagasta, Chile. Community Development Journal, 56(3), 449–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara-Perucich, J. F., & Boano, C. (2019). Vida urbana neoliberal: Estudio de factores de jerarquización y fragmentación contra el derecho a la ciudad en Chile [Neoliberal urban life: Study of hierarchization and fragmentation factors against the right to the city in Chile]. Revista de Direito da Cidade, 11(1), 426–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfgring, C., & Peverini, M. (2024). Housing the poor? Accessibility and exclusion in the local housing systems of Vienna and Milan. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 39, 1783–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

| Period | Sociopolitical Context | Main Measures | Outcomes/Impact | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1919–1934 (Red Vienna) |

|

|

| Essletzbichler and Forcher (2022); Eder et al. (2018) |

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

| 1934–1945 (Interwar & WWII period) |

|

|

| Essletzbichler and Forcher (2022) |

|

| |||

| Postwar (1945–1960s) |

|

|

| Franz and Gruber (2018); Essletzbichler and Forcher (2022) |

|

|

| ||

| 1970s–1980s |

|

|

| Eder et al. (2018); Franz and Gruber (2018) |

|

|

| ||

| 1990s–early 2000s |

|

|

| Marquardt and Glaser (2023); Aigner (2019) |

|

|

| ||

|

| |||

| 2000s–present |

|

|

| Aigner (2022); Banabak et al. (2024); Eder et al. (2018) |

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

| Thematic Axis | Lights (Positive Aspects) | Shadows (Negative Aspects) |

|---|---|---|

| Institutional Stability | Strong continuity of the public housing system supported by clear rules, long-term planning, and firm political will (Kadi & Lilius, 2024). | Dependence on stable institutional structures, which may exhibit rigidity in the face of crises or abrupt political changes (Marquardt & Glaser, 2023). |

| Accessibility and Affordability | Broad provision of public housing and rent control reduce pressure on the private market and benefit middle-income groups (Franz & Gruber, 2018). | Structural exclusions persist: refugees and the poorest segments of the population face access barriers and are pushed into precarious submarkets (Aigner, 2019; Wolfgring & Peverini, 2024). |

| Socio-Spatial Equity | Low socio-economic segregation in the European context; equitable access to urban amenities (Morawetz & Klaiber, 2022; Tammaru et al., 2015). | Recent widening of social gaps; the ideal of “social mix” does not necessarily translate into neighbourhood cohesion or meaningful interaction (Unterdorfer, 2016). |

| Resistance to Financialisation | Effective public regulation has curtailed large-scale privatisation of the housing stock (Kadi & Lilius, 2024). | Subtle re-commodification processes through instruments such as the Vorsorgewohnung, which increase prices and undermine affordability (Aigner, 2022). |

| Social Innovation and Alternative Models | Emergence of collaborative housing initiatives (habiTAT, Baugruppen) aiming to re-politicise housing and counter market logic (Hölzl et al., 2022; Schikowitz & Pohler, 2024). | Structural and regulatory limitations imposed by the public apparatus; still marginal institutional support hampers scalability (Schikowitz & Pohler, 2024). |

| Symbolic and Cultural Dimension | Presence of utopian architecture such as the Hundertwasser-Haus and neighbourhoods with strong local identities (Babos et al., 2024). | Disconnection between the symbolic ideal of dwelling and the lived experiences of residents (Kraftl, 2007). |

| Social Sustainability | Civil society–state alliances promote more inclusive and participatory governance models (Paidakaki & Lang, 2021). | Institutional exclusion of non-normative family configurations and limits to effective participation persist (Paidakaki & Lang, 2021). |

| Environmental Sustainability | Ongoing initiatives aim to link social and environmental justice in urban planning (Novy et al., 2001). | Continued emphasis on expansion rather than rehabilitation weakens climate justice goals (Novy et al., 2001). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vergara-Perucich, F. Can Public Housing Truly Be Innovative? Lessons from Vienna to Reimagine the Future of Local Governance. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 233. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060233

Vergara-Perucich F. Can Public Housing Truly Be Innovative? Lessons from Vienna to Reimagine the Future of Local Governance. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(6):233. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060233

Chicago/Turabian StyleVergara-Perucich, Francisco. 2025. "Can Public Housing Truly Be Innovative? Lessons from Vienna to Reimagine the Future of Local Governance" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 6: 233. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060233

APA StyleVergara-Perucich, F. (2025). Can Public Housing Truly Be Innovative? Lessons from Vienna to Reimagine the Future of Local Governance. Administrative Sciences, 15(6), 233. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060233