1. Introduction

This theoretical article explores the social phenomenon that is referred to as charisma in leadership theory and practice (

Bryman, 1992;

House, 1977,

1999). It is an attempt to better understand what charisma is and how it might impact individual choices during the leadership influence process (

Hazy & Mahmoodi, 2024) in social systems. Traditionally, most studies of charisma have focused on the attributes and behaviors of individuals who are considered to be leaders during their interactions with followers. Studies of this type attempt to explain how certain approaches to leadership elicit a reaction in others that creates in them a desire or willingness to follow the leader, sometimes even blindly (

Conger & Kanungo, 1987).

In contrast, this article focuses primarily on followers’ experiences during social interactions that involve the social influence that is associated with leader/follower relationships. It attempts to explain how individuals come to report what one might call a charismatic experience. In the context of individual choices and action, this experience is posited to reflect an event wherein an autonomous individual-as-agent effectively flips from a state that involves evaluating and making individual choices autonomously to a state where that individual simply imitates the choices, trajectories, and periodicities of another individual. In these situations, the imitated individual is often called a charismatic leader.

To address this gap in the literature, the argument put forth in the following pages makes four assertions. Firstly, it acknowledges that the term charisma is most often used to describe a constellation of attributes observed in an individual. For example, an individual who attracts attention by opposing the status quo, by taking personal risks, by expressing confidence or commitment to a vision or a needed change, or by demonstrating the ability to elicit trust in others (

Conger & Kanungo, 1987) is likely to be called charismatic. However, this article also acknowledges the more recent observation of

Conger (

2015) and others, that when considered objectively, the experience of charisma actually resides in the reactions of the followers of an individual who is perceived to exhibit one or more of these characteristics. Furthermore, it is the experience of charisma as it is felt by a follower that results in the attribution or tagging of being charismatic to another individual. In this sense, charisma, like beauty, is in the eyes of the beholder.

Secondly, this article postulates that at its core, followers’ experience of charisma accumulates its power not from an individual leader but because it involves a new cognitive positioning of an individual’s self-concept within a particular context. This redefinition involves the adoption of an abstract generalized representation of unfolding events that describes a specific context for action that is relevant to that particular individual (

Sims, 2018;

Fang & Sims, 2025). When the adoption of a charisma-inducing representation occurs in the context of the continuing presence of another individual with whom they are familiar and whom they have chosen to imitate or follow, they might tag that individual as a charismatic leader. As a result, this leader–follower dyad in now included in a follower’s representation-of-events. Thus, when an individual acts or makes choices in the relevant context, the definition-of-self, or self-concept, of a follower can be thought of as at least partially subsumed as a dyad within a social network. Rather than remaining an independent autonomous agent, this new contextualized self-concept (

Epitropki et al., 2017) effectively becomes a follower. Although this implies benefits, it also suggests there are risks.

Thirdly, if the argument put forward in the following sections is assumed to be true, then individuals, that is, followers, who implicitly surrender some of their decision-making authority to another individual due to a charismatic experience could assume a great deal of risk if the decisions being followed are not well considered. Thus, the charisma experience and what it implies could fairly be considered to be a previously unidentified cognitive bias (

Kahneman, 2011). Fourthly and finally, if supported empirically, this argument suggests that there are serious ethical challenges associated with teaching would-be leaders the behaviors, attributes, and communication styles that are known to illicit the charismatic experience in uninformed others.

Overall, my argument can be summarized as follows: The notion of charisma in leadership studies can be reconceptualized as a positive affective cognitive response in a follower (

Lord & Brown, 2004;

Cristofaro, 2020). More specifically, it is one that arises when individuals recognize themselves within a familiar shared representation of the dynamic social structures that organize events. Because the presence of these structure influences individual choices and behaviors in familiar ways, this “familiarity response” can be experienced as charisma absent specific knowledge about why it feels familiar. As the well-known psychology researcher,

Ranganath (

2024), recently put it: “We often (mis)use familiarity as a heuristic, or mental shortcut, to guide decisions. Moreover, we can be blissfully unaware of these influences and instead reinforce our sense of free will by constructing stories that assign meaning to our choices and actions” (p. 113). In this case, perhaps the story involves the presence of a charismatic leader.

This situation can be problematic, however. If another individual, a leader, is positively identified with the experience, they may be called charismatic. Fortunately, in organizational settings, the structures that are recognized as familiar are shared publicly. They are often called shared mental models (SMMs), and therefore are available for independent analysis. This is where an abstract mathematical field called category theory can be used to deconstruct and formally evaluate the efficacy of a representation of events before it is broadly adopted. Potentially, this could be achieved with the help of new AI technologies.

The category structures and methods described herein could be used to enable individuals and groups to, independently or collectively, perform formal analyses of the practical realities that underlie the leadership influence that is triggering a charismatic experience. Before blindly accepting charismatic influence, each person could potentially and independently evaluate and periodically re-evaluate the risk/benefit tradeoffs that flow from that influence when deciding whether or not to continue to use the charisma heuristic by choosing to imitate or follow the directives of a charismatic other. The next section begins to describe how this is achieved.

1.1. Method Used to Develop Theoretical Framing

This theoretical article frames its questions and makes its assertions conceptually by using a novel but disciplined analytical approach. In particular, to construct a representational framework that describes leader and follower interactions within a specific context, it uses an abstract mathematical approach called category theory (

Mac Lane, 1978;

Goldblatt, 2006;

Spivak, 2014). This most general branch of mathematics is often used to logically apply results from one area of mathematics to another seemingly unrelated field. As is described in later sections, category theory ensures that if all rules are followed, then the result will be mathematically correct.

Category theory is used practically as well. In computer science, when mapping a business or technical problem to an information technology application, an abstract category is used for data modeling and database design (

Spivak, 2014). More recently, it has been used to study data models and methods used in generative AI transformer models (

Bradley et al., 2021). These studies explore the information content embedded in syntax and semantics in technology-enabled data storage, access, processing, and communications.

The category theoretical approach to causal modeling (

Jacobs et al., 2019;

Otsuka & Saigo, 2024) used herein and discussed in more detail in

Section 3 offers abstract models that suggest new theoretical perspectives on the genesis and implications of a follower’s experience of “charisma”. As an example, when modeling the leadership influence process by using agent-based modeling (ABM) (for a recent review, see

Hazy & Mahmoodi, 2024), a human collective, in an abstract representation, can be considered to be organized into a dynamic and directed complex social network. This is a network in which individual agents are represented as nodes making choices, including with whom to interact, whether to cooperate with that agent, or whether to imitate the choices of another agent. In these models, interactions between agents are directional edges with various weightings with respect to each of the three degrees of freedom mentioned above (

Mahmoodi et al., 2020).

In the current context, one could argue that when an agent assigns the trait of “charisma” to another individual, thus tagging that individual as a “leader”, the first individual effectively self-identifies as imitating the leader-tagged agent along the imitate-choices-of-another dimension in the above representation. Thus, as a directed dyadic element in an abstract representation of events, “social influence” radiates from the leader agent to follower agents and serves to synchronize the choices of individuals who are subject to leadership influence. This directed social network model, therefore, is a relatively simple example of how a categorical representation, here as a directed social network, can be used to identify potentially fruitful areas for future empirical research.

1.2. Venture Team—Scenario #1

To help illustrate the practical implications of the categorical approach described herein, we will follow a stylized description of an entrepreneurial team as they frame their vision, assess risks, both for the venture and for the individuals involved, and ultimately make and evaluate decisions, often by relying on heuristics (

Cristofaro & Giannetti, 2021).

Consider an eight-member venture team led by a visionary entrepreneur, of the Steve Jobs or Bill Gates type, who imagines and enthusiastically promotes products and services that customers might want. In addition, there is an engineering technologist, of the Steve Wozniak or Paul Allen type, who works diligently to make products that work. Although no formal reporting structure or hierarchy is assumed in this example, there are also other members of the team, including three technology workers who interact mostly with the engineering technologist, and three managers who mostly interact with the visionary entrepreneur. In future scenarios, this article follows the leadership in this venture team.

1.3. Overview of the Argument

The overall argument proceeds as follows: In

Section 1, the experience of charisma is defined for this analysis as the redefinition of self-concept in the context of action within an explanatory representation of events that includes interaction with others.

Section 2 briefly reviews the relevant literature on charisma. It also identifies research gaps and frames four research questions to address them.

Section 3 is a first attempt at applying conceptual ideas from the mathematical category theory to social contexts and to leadership in particular. It introduces category theoretic mathematics as a rigorous surrogate for sharing, communicating, and acting within higher-level thinking processes among human beings. This relatively new field of mathematics was constructed in the early twentieth century to extend the applications of set theory while at the same time avoiding some of the paradoxes that were identified during that time (

Russell, 1908).

Section 3 is only intended to introduce some important intuitions that category theory might offer when rigorously applied.

Section 4 recapitulates some of the key arguments in

Section 2 and

Section 3, and while doing so frames eight propositions for future research. This time, however, it treats category theory as a consensus framework that enables the externalization, communication, and evaluation of higher-order cognitive processes for collective consideration. It suggests that category theoretic representations can be shared and used to provide transparency regarding a leader’s plans so that followers can locate themselves in the representation and only then decide whether, and if so how and where, they fit within them. The framework is posited to serve as a surrogate cognitive model for considering the implications for individuals of changing their self-concepts in relation to higher-order organizing structures in social systems. This approach may be helpful when exploring how best to implement effective shared leadership approaches.

Section 5 offers a discussion of the implications of this analysis for future research, as well as pointing out some of its limitations. The article concludes by challenging researchers to consider the ethics of training individuals to engage in charismatic leadership tactics (

Antonakis et al., 2011). These tactics are, it may seem, designed to enable individuals to position themselves as charismatic leaders for the purpose of gaining power and influence absent an understanding by followers of the efficacy of the underlying representation that is being used to activate the charismatic experience. This article suggests that it might be appropriate for leadership training to insert a reflective and transparent step into the leadership process. This ethical imperative would require that before leaders engage in charismatic leadership tactics, they must first provide a transparent and rigorous category theoretic analysis of the vision, mission, or operating plan that is being proposed. This analysis, which could potentially be performed with the support of new AI technologies, would enable potential followers to freely make informed choices about whether or not to accept the experience of charisma, and thus, by choosing to do so, undergo a potentially life-changing redefinition of their self-concept.

2. Theoretical Framework: The Experience of Charisma in the Literature—Four Research Questions

Prior research has most often explored the notion of charisma in the context of the quality or ability of an individual leader to cause changes in the behaviors of others (

House et al., 1991;

Jacquart & Antonakis, 2014;

Waldman et al., 2001). This approach led to studies that described differences in individual physical attributes, behaviors, and communication patterns that were shown to result in the assignment of charisma to a leader by a follower. Some of these attributes include requisite abilities such as judgment, decision making, persuasive communications, and risk taking, as well as personality characteristics such as being high-energy and enthusiastic, self-actualized or tolerant of ambiguity, generous, open, self-confident, articulate and expressive, or concerned with the needs of others (

Bass, 1990, pp. 188–192).

Considerable research has also studied leadership and followership from the perspective of their impact on the intrapersonal, interpersonal, and social identities of individuals and how these interactions impact their individual self-concepts (

Epitropki et al., 2017). For simplicity, I follow

Shamir et al. (

1993) and refer to these collectively as aspects of one’s self-concept in the context of a charismatic experience. Taken together, this research deeply informs the field about the impact that leadership interactions, including charismatic leadership interactions, have on the self-concepts of both leaders and followers, as well as how leader–follower interaction impacts their perceptions of others.

It has also been acknowledged that this one-way directional influence model of charismatic leadership raises ethical concerns. For example,

Ciulla (

2005) observed that “The fact that a leader possesses these traits does not necessarily yield moral behavior or good moral decisions” (p. 320). She also wonders what happens to those followers who would prefer different goals and outcomes. The point here is that just because an individual can inspire others to follow, this does not directly imply that a leader is going in the right or even in a reasonable direction. This realization suggests a further gap in the literature that is related to ethical concerns associated with the presence of charismatic relationships in a collective. In addition, it also raises questions as to the risks associated with leadership development programs that promote and teach these, admittedly successful, approaches to forming dyadic leader–follower relationships based on charisma, but which can also potentially blind followers to their own best interests.

It is not surprising, therefore, that this one-way directional framing has recently come into question (

Conger, 2015;

Waldman et al., 2001). This change is due, for example, to the recognition that there are differences in the experience of charisma associated with both a follower’s tolerance for uncertainty and the social context of the follower within which the leader–follower interaction unfolds. Each of these differences can impact the nature and intensity of the charismatic experience in a follower (

Klein & Delegach, 2023). These follower-centric findings, in combination with the research into identity and self-concept in leader and follower relationships, suggest that there are conceptual problems with the traditional behavioral theories of charismatic leadership (

Conger & Kanungo, 1987). In particular, this suggests the need for additional research with regard to the nature of the charismatic experience, its causality, and its implications (

van Knippenberg & Sitkin, 2013;

Yukl, 1999).

2.1. Venture Team—Scenario #2

In the context of the entrepreneurial venture team example, it is easy to imagine that a visionary entrepreneur, like Steve Jobs or Bill Gates, is in the position as the only one of the eight team members who is fully invested in the venture idea and who appears to know where the venture is going. It makes perfect sense that others in the group, with the possible exception of the technology members, would blindly follow the visionary leader. Initially, one would expect that individuals would maintain an independent self-concept, the “I just work here” period. However, once a few successes have occurred, one can imagine the shared pride of accomplishment beginning to impact some members’ cognitive self-concept, perhaps even to the point of blind allegiance.

At the same time, the technical team is in a position to understand the details of the current situation and the future vision. This team and their work products can effectively act as the detailed mathematically formalized roadmap in the present and into the future. One can imagine a separate technical plan, in a way analogous to a mathematical categorical framework (

Spivak, 2014), in parallel with the entrepreneurial vision guiding the team into the future. There is a balancing perspective in the venture: “We can only do what is possible!” The question therefore becomes the following: Does this alternative perspective serve to balance the influence of the charismatic experiences initiated by the visionary leader, and by doing his, serve to inform individual choices of the eight team members?

Considering the above scenario, this article identifies four research questions that are intended to inspire future empirical research studies.

2.2. Four Research Questions

This theoretical article asks and explores four research questions, each building on the assertions of the prior ones. It also frames eight propositions to address these questions.

Table 1 summarizes the questions and suggests a research program intended to test each of these in sequence.

The first research question is as follows: Under what circumstances does a redefinition of one’s self-concept, that is, an event that replaces a prior self-concept with a new and different one, occur during leader–follower interactions, and under what conditions is the new definition shaped by the context under which the change occurs? The second research question considers the relevance of context. It asks the following: To what extent does an experience that is identified as charisma felt by individuals relate to the emergence of consensus among these individuals around a shared representation of events? Herein, this shared representation is called a shared mental model (SMM). This term is often used in computational management science (

Hazy & Mahmoodi, 2024) to describe the common perspective of the opportunities and threats facing a collective.

It is important to note that an SMM is a generalized abstract representation of events in the social and physical ecosystem (

Sims, 2018;

Fang & Sims, 2025) that is shared among individuals through communication of various types. It is not the actual landscape. An SMM is thus a generalized abstraction, or map, and the map is not the territory, as

Hayakawa (

1939,

1978) famously wrote. When representations of events, that is, SMMs, are rigorously constructed and tested, they can be used as heuristics for predicting the likely interactions among people or things in the real world.

In this sense, although SMMs may bring heuristic benefits to individuals who adopt them as a way to simplify their choices and actions, blind adherence to them carries with it a significant risk. Thus, as heuristics, when an SMM is shared with others and adopted broadly to organize events, it is often accepted implicitly without rational awareness of the ways that the real world has indeed been simplified. Thus, our third research question is whether a charismatic experience can be classified as a cognitive bias which must be overcome for effective decision making. Furthermore, can category theory as a mathematical body of knowledge be a useful tool to mitigate this risk?

Taken together, these points suggest a fourth research question: What are the ethical considerations when training would-be leaders about how they can trigger a charismatic experience in followers that may, in the end, be harmful to those individuals who follow or potentially be corrupting of the organization they support. The question becomes the following: Should a critical analysis of an SMM using rigorous tools such as mathematical category theory, or other approaches such as process analysis approaches like those described in

Hazy et al. (

2023), be a required step when formulating the charisma-triggering story or presentation that communicates to a collective or to an organization’s members? And furthermore, under what conditions should this analysis be made available to those who may be impacted? These four research questions, along with a four-step research agenda to address them, are summarized in

Table 1.

3. Materials and Methods: Category Theory Applied to Shared Mental Models in Social Systems

This article takes the philosophical position that, as a discipline, the study of mathematics seeks to understand what can be inferred about well-defined relationships among abstract “objects”. These objects can be taken to represent events that are observed, recognized as familiar, imagined as possible, or remembered (

Ranganath, 2024) by individuals through experience

1. Its pursuit is general and abstract, and is taken to include objects that might reflect an observation in the objective sense. However, objects within a representation might also include purely abstract or subjective objects that are only “observed” as a perceived pattern or “type” (

Russell, 1908). The theory of complex numbers offers an example of this. Although purely abstract, complex numbers, which incorporate the imaginary number

i = have been shown to have many practical applications that were never contemplated when they were conceived (

Penrose, 1989).

This paper posits that mathematics can be thought of as a reproduceable and verifiable symbolic language that uses rigorously tested abstraction to reflect and communicate among groups of individuals using shared representations of higher-order cognitive processes that are occurring in the human brain and experienced in the minds of human beings (

Lakoff & Nunez, 2000). Through the mechanisms of expert consensus, the syntax of mathematics has been constructed over centuries to rigorously describe abstract objects and relationships among them that, as shared abstractions, can be taken to reflect higher-order cognitive processes. These in turn have been demonstrated to imply other propositions that can be deduced through abstract reasoning. As such, mathematics is applied herein as a useful surrogate for understanding the processes of human cognition as applied more broadly in social networks and during social interactions (

Hazy & Mahmoodi, 2024;

Tomasello, 2014, p. 143;

Bradley et al., 2021).

In this philosophical context, mathematics does not necessarily refer to the use of equations or even quantification, although these are tools that mathematicians often employ. Rather, this paper looks to one of the most abstract areas of algebra called category theory, which seeks to represent abstractly the general principles that apply to many specific types and instances of observed relationships and event. These include logic (

Goldblatt, 2006), linguistics (

Partee et al., 1990, p. 254), and computer science (

Spivak, 2014), as well as traditional areas of mathematics (

Mac Lane, 1978). Math has a long and successful history as a means through which to create logically consistent syntactical representations of observable or predictable events and quantities, and provides a mechanism with which to assign a representation a syntactic value of either true or false.

In high school algebra, for example, variables are substituted for numbers so that a single general equation can be used to describe an infinite number of specific cases. Category theory takes this approach to even higher levels of abstraction. It attempts to extract from the many specific areas of mathematics the essence of what is meant by a mathematical relationship (and thus other cognitive relationships) to understand what such relationships might imply.

All mathematical representations—and therefore all conditions for which mathematics can be usefully applied to frame and understand the dynamic structure of relationships among objects—are shown in category theory to be represented as a single abstraction, the mathematical category. Thus, many quantitative methods used in social science, statistical analyses, and linear or nonlinear regressions, even the logic behind conceptual frameworks that specify relationships among variables (

Spivak, 2014), can be framed in category theoretic terms. Even formal logic (

Goldblatt, 2006), linguistics, and semantic analyses that are core to qualitative coding methods can be framed in category theoretic terms (

Partee et al., 1990, p. 254). One could even argue, I believe convincingly, that if a researcher cannot construct a categorical representation to describe the phenomenon, one cannot legitimately claim to use mathematics—even statistical analysis—in that context.

In its simplest instantiation, a mathematical category is defined as follows: (1) a collection of abstract objects, for example, individuals in an organization; (2) a directional relationship that maps one object to another, for example, direct communication where X maps to Y; (3) an identity relationship, such that each object maintains its structure when X maps to X; and (4) mappings can be composed and the associative property holds such that for any object, X, Y, and Z, the result is the same whether X maps to Y and then the result maps to Z, or Y maps to Z and then X maps to the result of the Y map to Z. Together, these properties define the simplest mathematical category. Additional assumptions can be added, but these four assumptions must apply.

One of the most commonly used categories is the category of sets (

CSET), which is a generalization of set theory. One basic result from category theory is that if one can map the abstract objects and relationships of their representation of a phenomenon to

CSET, then all of the results of set theory apply. Category theory is used more generally in a similar manner, that is, by mapping a generalized representation of a phenomenon into an abstract category. For example, in data modeling and database design (

Spivak, 2014), operational activities are represented abstractly by organizing them into categorical structures. More recently, these techniques have been used to study the data models and methods used in generative AI transformer models (

Bradley et al., 2021). These prior studies have explored the information content of language that is embedded in syntax and structure.

Category theory, as the most general form of mathematics, is one of the higher-order thinking processes that characterize human development. These are “built on universal cognitive processes but with culturally constructed manifestations” (

Tomasello, 2014, p. 143).

3.1. Illustrative Category Example #1: Define Category Cm of a Community of Members

Consider the case where an individual agent chooses to construct an abstract generalized self-concept that represents itself and is defined to be an individual object, m1, in a category, Cm, that is defined to consist of members, mi, of a specific community, C. The agent further defines the identity mapping as mi → mi = mi, which simply assumes that each object maintains its identity. If one further requires that the identity map is subject to composition and the associative property, which in this case only means that the ordering of multiple identity mappings is still an identity map, then this abstract representation meets the definition of a category. Because the conditions for categorical representation are met, but no other mappings among the mi are defined, the objects are discrete. Therefore, this is called a discrete category.

With a category theoretic structure as a starting point, one can ask the following: If the category representation is “true” in some semantic sense, then what other statements can be deduced as also “true” in that same semantic sense? It turns out that the answer is quite a bit (

Mac Lane, 1978;

Spivak, 2014). Even in the above very simple illustrative category example #1 case, one can assume that absent any additional assumptions, any self-aware human being who is a member of

Cm is subject to an identity map and therefore includes a self-concept that is stable over time. The remainder of this section provides an overview of some basic ideas from this field and how they might apply to leadership relationships. However, it does so at a conceptual level without formal derivation. For a more formal and complete presentation of this material, the reader is referred to

Spivak (

2014) for cases of scientific and information technology applications,

Goldblatt (

2006) for logic, or

Mac Lane (

1978) for a purely mathematical treatment.

3.2. Category Theory Basics

Category theory seeks to understand what can be inferred in general about abstract “objects” and relationships, called morphisms, between them. Taken together, objects and morphisms can the used to represent “events”. Objects might reflect an observation of a thing, such as a member of a community, in the objective sense. However, objects might also reflect a purely abstract idea, like a random variable, that is only “observed” in the sense that a perceived pattern is identified and treated as a conceptual object. In any case, objects are abstractions, pure and simple. They exist as information that is encoded in the mind or in the physical world (

Fang & Sims, 2025). They are not real in the objective sense. Objects are the building blocks that are used to construct category theoretic abstract representations that can act as generalizations of some postulated structures that include, in their structure, stored information that can be decoded by whomever is using them to understand and make choices in a particular context (

Fang & Sims, 2025).

3.2.1. Some Background in Category Theory

Category theory (

Mac Lane, 1978) as a mathematical discipline was born in the early twentieth century as an outgrowth from the debates among mathematicians including

Russell (

1908), Alfred North Whitehead (

Russell & Whitehead, 1910,

1912,

1913), and

Poincaré (

1913/1963) as they struggled to resolve questions about the relevance and efficacy of mathematics in the face of paradoxes that had been identified in traditional set theory, particularly the theory of infinite sets. Evolving eventually from Russell’s theory of types, category theory resolves many philosophical issues that arose after Gödel’s incompleteness theorem (

Goldstein, 2005). Category theory does this by distinguishing collections (rather than sets) of information that are stored in structures that are organized into distinct layers or “orders” of definition. These layers and axioms are constructed to explicitly exclude conditions that had been identified as paradoxes.

Category theory unites many fields of mathematics under a common axiomatic framework. These fields include algebra, Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometries, topology, complex analysis, dynamical systems, statistics, set theory, and graph theory. Applications of its theorems also apply to formal and informal logic (

Goldblatt, 2006), rigorous treatments of linguistics, and formal explorations of semantics (

Partee et al., 1990, p. 254), as well as many technical applications, including computer programing and database structure and access (

Spivak, 2014). More recently, a version of category theory, called “enriched category theory”, has been used to better understand how chatbots in generative AI models construct their responses to user prompts (

Bradley et al., 2021).

It is not at all controversial, then, to claim that theorems from category theory are an important reason why statistics, which are known to apply to physical particles, can also be used syntactically to represent human preferences in psychology. Note that it is also why one might add the caveat that the assertion can be assumed to be true only if the findings of category theory are shown to apply in the representations used in studies. Similarly, economists or evolutionary biologists apply the syntax of dynamical systems theory even though it was originally developed by

Poincaré (

1913/1963) in the context of the three-body problem in celestial mechanics. Routinely, results in one field of mathematics are used to prove theorems in other fields; a proof in topology might be used in geometry, for example. By using theorems from category theory, mathematical results can be applied across disciplines with confidence in their syntactic validity. However, the semantic truth of what mathematics might imply in any practical social context is a separate question that is touched upon in a later section of this article. Furthermore, if the tenets of category theory are not rigorously applied when crossing disciplines, the misapplication of analogical insights born in one field and then applied in another can lead to false or misleading conclusions.

3.2.2. A Category Defined

Any category is constructed to represent a distinct level of scale, or of “order”. Although objects in a category can themselves be shown to be categories in their own right, but at a lower level of scale, each category is defined as a layer of an informational structure. Each category is completely defined in mathematical terms at a level of scale, as objects, relationships among objects, and properties of these relationships. More specifically, a category is defined as follows:

An object in category theory is the basic structural unit of encoded bit-level information at a level of scale. The object is either included, True = 1, or it is not included, False = 0. Thus, it is a generalization of an element in set theory. At the same time, however, the same object can also include additional information within its own category structure, which can be accessed and decoded at a lower level of scale.

For all objects, there exists an identity map, called the “identity morphism”, that maps an object to itself in a way that preserves that object’s sub-object informational structure if any exists.

If there are other morphisms from one object to another, these can be performed in sequence, such that the result is equivalent to defining a morphism directly from the first object to the last, that is to say, morphisms are subject to composition.

In composition, the order of the operations does not matter, which is to say, the associative property holds.

Note that for a generic abstract category to be defined, that is, it is True = 1, nothing else needs be assumed.

In its most general form, there are no numbers and no equations (

Mac Lane, 1978;

Spivak, 2014). There are objects, maps or relationships with defined properties, and importantly, the identity map. This latter assumption is critical because it enables predictability over multiple iterations. However, one should also note that a categorical representation is a subjective abstraction, a generalization of observed and decoded information associated with real-world events. It is not an objective fact (

Sims, 2018;

Fang & Sims, 2025).

3.2.3. Illustrative Category Example #2: The Influence Morphism Defined as a Follower Accepting Influence

In the case of leadership influence interactions, a dyadic relationship between two individuals can be represented by constructing a category. Keeping the focus on the object that is being influenced, called the follower, one begins by defining two objects, x

1 and x

2, to represent individuals, “agents”, each with an identity morphism. Next, one adds a single additional morphism,

f: x

1 → x

2, which is intended to represent the acceptance of influence from x

1 by x

2. (Note also that the morphism

f: x

2 → x

1 is also implicitly defined.) If one continues the construction to satisfy the requisite properties for a category, then this abstract construction becomes a simple category theoretic representation of a directional leadership influence process (

Hazy & Mahmoodi, 2024). This representation will be called

CInfluence. (Note that this is intended to be used as an illustration only. Many aspects of what researchers study as “leadership” are not represented in this very simple category.)

3.2.4. Increasing Orders of Scale in Category Theoretic Abstraction

As one might imagine, it is straightforward to show that the simple leadership influence category

CInfluence is isomorphic with the analogous category of a directed network with objects as vertices and morphisms as arrows (

Spivak, 2014). Maps between categories, called “functors”, establish this isomorphism by taking objects to objects, morphisms to morphisms, and identity morphisms to identity morphisms in a manner that preserves the categorical structure. Thus, what is true in one category is likewise true in the other but only at the level that is defined in the category theoretic representation. Other details not represented at the same level of representation can vary, for example, differences may exist at levels of order that are either above or below in the scale of the representation. The collection of functors and the maps between these categories may likewise form a category of a different level of order if it is constructed according to the categorical laws.

Thus, one does not have to stop with the simple dyad described in CInfluence of the illustrative category example #2. More information bits can be embedded into a representation at the same or at a higher level of order. For example, a second morphism, g: x1 → x2, can be added so as to construct a new category, indicating that a different type of influence also flows, perhaps related to different projects or different roles. Each of these would be isomorphic to a (different) directed graph category, and so on. Each addition of further structures forms a new category that is defined separately. In many cases, morphisms, called functors, can be defined between these categories. The categories thus become “objects” at a different level of scale, and morphisms can be constructed such that a higher-order category can be defined.

3.3. Venture Team—Scenario #3

We can see these more complicated categorical representations in the entrepreneurial venture team example. In this example, there are two distinct and yet complementary categorical informational structures. One of these is the visionary influence on the team that is articulated and reinforced by the entrepreneurial visionary, the Steve Jobs-type leader. Each of the other seven team members feels the influence of the visionary representation. At the same time, however, influence also flows to each of the other seven members from the technology platform, from the Steve Wozniak-type leader. One might think of these dueling representations as the complementary, sometimes conflicting, “go big” visionary versus “be practical” influence flows that, when effectively navigated, can lead to both visionary and successful outcomes (see

Linzmayer (

2004) and

Wozniak and Smith (

2006) for more on Apple’s founding).

From the perspective of the followers, however, each individual is effectively left to either choose one of the flows to follow or to navigate between the flows of influence toward a successful outcome for each member individually. In the context of their individual self-concept in service to the venture, each would seem to have the opportunity to maintain autonomy by choosing which influence flow, that is, which boss, to follow for a given task. Next, we look at why the choice to follow the influence of either the visionary or the practitioner often fades away.

3.4. The Heuristic Value of Universal Properties: The Limit and Colimit

Universal properties are abstract objects constructed within categories that enable what will be called “completion” and “closure” within the category. The universal property called completion involves the existence of the “limit”. This is constructed by adding an initial object that has an arrow (or morphism) that points to (terminates at) every object in the category. In the case of the illustrative category example, the limit would be an additional abstract object in the category, defined as the cross-product of all of the objects in the category, which is analogous to the empty set in set theory. It thus maps to each object in the category. In contrast, closure involves the colimit, which is defined as the direct sum of all of the objects and thus can be reached via a map from any object in the category.

Completeness, or the limit, is effectively the object of possibilities, if you will, and as a result, there is a map (a morphism) from the limit to every object whether through a direct or composite path. As such, it is defined as the “cross-product” of all of the objects in the category. In algebraic terms, for objects x, y, and z, one might think of this as the space created by the graph of the orthogonal, x-axis, y-axis, and z-axis, etc., but with no points identified on the graph. In the case of individual human beings making use of CInfluence as their abstract representation, or generalization, of the leadership influence network in the work environment, the addition of the limit object effectively empowers the pronoun “we”, where for each participating member “we” maps to “me”, as in a group or herd mentality. Social influence derives from the information embedded through the adoption of completion, a limit, in a generalized representation, CInfluence, used to make individual choices.

Thus, this generalized influence flows not from another individual, but from the member’s act of adopting, that is, including one’s self-concept as an object in, the category CInfluence. The limit effectively creates a space of possibilities available only to those who are included in the category. It adds completeness, and therefore is, by itself, a source of leadership influence because it communicates what “we are doing”. By including their self-concepts as objects in the CInfluence with the limit included, individuals immediately feel generalized influence. Perhaps this same argument explains the genesis of peer pressure in groups.

In contrast, the universal property called the colimit enables “closure” by adding a terminal object to which there is a mapping (a morphism) from every object. The colimit represents all of the objects that are included in the category. As a result, for every object in the category there is a direct or composite map (a morphism) from that object to the colimit. This is defined as the “direct-sum” of all of the objects in the category. In algebraic terms, one might think of this as the object that includes all objects. Thus, each object can be mapped to the colimit either directly or through a composite map (or morphism). The addition of a colimit to those who have adopted CInfluence enables them to know and to say “this is us”. The representation, CInfluence, with both limit and colimit universal properties, is herein denoted CUPInfluence.

3.4.1. Universal Properties and Their Implications

The universal properties of limits or colimits are “universal” in the sense that each object has a relationship with either the limit or the colimit or both, whether the mapping begins or ends there, respectively. Stated more formally, the “limit” can be thought of as the initial object that is the broadest domain from which there is a path or arrow (perhaps though a composition of maps) to all objects in the category. Conceptually, the limit provides completeness as a generalized cross-product, like the space formed by the x- and y-axes in geometry, that is, all objects are included in this space, but with additional structure (

Spivak, 2014). Likewise, the “colimit” can be thought of as a terminal object that is the smallest codomain to which all paths eventually lead or terminate. Conceptually, the colimit is a generalized disjoint union or direct sum of all objects (

Spivak, 2014) that provides closure by assuring that all sums are included in the category. Taken together, the universal properties provide both completeness and closure, and thus describe common attributes of all objects in the category. They all follow the syntactic rules defined by their shared relationships.

What is relevant in the context of this article is that for a categorical representation to include the universal properties of limits or colimits, it may be necessary to redefine which objects are included in the collection of objects in the category and which are in some way outliers, and as such must be excluded to in order to admit the universal property into the category. This reconstruction of the category might involve eliminating some objects that cannot be reached along maps from the limit or from which there is no mapping to the colimit. One can think of this abstract reconstruction as a rigorous filtering and purifying process intended to clarify and maintain the purity of the category. On the one hand, one must identify the broadest definition (the limit) of exactly which collection of objects and which morphisms are to be included in the category (because there is a path from the limit to any object in the category). On the other hand, one must identify the narrowest definition of structure (the colimit) that can be deduced about the objects in the category (because there is a path from any object in the category to the colimit).

The construction of a complete and closed category theoretic representation (complete and closed since it is constructed so as to include both a limit and colimit) by adding universal properties is straightforward in the abstract and is consistent with commonly accepted branches of mathematics. As such, it can be taken to be a requisite syntactic discipline necessary for clarifying a common reasoning framework that enables the sharing of complicated thinking processes about specific topics within a group of individual human beings who share a common context or perspective.

However, it is an abstract generalization of observation. It is not always semantically true if it does not reflect the state of the objective environment: representations of social systems, when each individual can independently choose, or appear to choose, to align their individual self-concept as defined as an object within a representation that is both complete and closed to universal properties. If this representation is assumed to be semantically “true” by its members, there may be real-world consequences associated with observations and predictions that classify objects into the categories included in the representation.

3.4.2. Illustrative Category Example #3

Thus, if an individual includes their self-concept as an object in a leadership influence category CInfluence, like the one described in illustrative category example #2, and if the category has both a limit and colimit, then there must be a path from the limit to the self-concept as an object, and from the self-concept as an object to the colimit. Thus, there is a possibility that, for a given object, the relevant self-concept as an object may need to be redefined or modified in the context of the leadership influence category, now called CUPInfluence, for it to be included within the universal properties that characterize the abstract representation. Note that this redefinition would need to occur independently of whether the truth value of the representation is known to the agent or even tested by others whose self-concepts are included as objects in the category. Thus, the choice to include one’s self-concept as an object in a representation may require compromises when making individual choices. This effectively makes the choice to adopt the representation a heuristic. The next section explores how universal properties might trigger the experience of charisma.

3.5. Categories Closed to Universal Properties and the Experience of Charisma

Categories closed to both limits and colimits are said to be closed to universal properties. For clarity, a category that is closed will be denoted CUP to distinguish it from C, from which it was derived. Note that to construct CUP, it might be necessary to add abstract initial and terminal objects in C and that objects in C that are not along some path from the limit to the colimit must be excluded from C.

Thus, when constructing comprehensive representations of complex phenomena, in order to gain the category theoretic benefits and theorems of various fields of mathematics that derive from the inclusion of universal properties in a representation, the category often becomes much more abstract and less accepting of ambiguity or anomalies in the details. This requisite simplification of bottom-up complexity is the price paid for top-down deductive clarity (

Mahmoodi & Hazy, 2025). On the positive side, however, this same top-down categorical clarity also implies that rigidly falsifiable semantic hypotheses often arise as direct deductive consequences of the decision to assume the completion and closure of categories through the adoption of universal properties.

To illustrate the above, consider the use of a map that represents the urban train and subway systems in New York City. Because the map of the train and subway systems is a closed, albeit syntactic, representation of a real-world organized transit system, any individual, by using the map, can predict with complete clarity whether it indicates that a particular location is at (or near) a stop on the trainline and when the trains are scheduled to arrive. Importantly, they can even use it to make this prediction without ambiguity. This single bit, a yes or no, of clarity significantly reduces the cognitive load for the commuter. However, the map itself also ignores detailed information about the real-world system, for example, whether there are any mechanical problems or delays in the system. To illustrate, consider the hypothesis implied by the NYC subway map that the A-Train is supposed to stop at Time Square has a semantic answer: it is either true or false. (It is “true”, by the way.) However, this does not guarantee that the train will be on time.

3.5.1. Illustrative Category Example 4: Universal Properties and Charismatic Experience

In the context of the leader influence category,

CInfluence, thinking metaphorically, one can consider the universal property of completeness, or the limit which is defined to be the cross-product of member objects, to be the potential or idealized influence that each individual member has on each other member by virtue of being a member of

CUPInfluence. Metaphorically, this could be the genesis of the idealized influence of leadership that derives from the

initiating structure in the form of a vision, mission, or purpose, that is projecting upon (or mapped to) all member objects in the category. This might be by virtue of being a member, as reflected in the organization chart, process diagram, or list of employees. This idea is often described as the genesis of charisma (

Bass & Avolio, 1994).

Further, the universal property of closure, the colimit, which is the direct sum of all objects, implies the inclusion and belonging of one’s self-concept as an object, one of all the members in the colimit. Assuming a self-concept perspective (

Shamir, 1992) as this analysis does, closure or the colimit implies that a given individual agent belongs as a contributor to the category. The idealized influence of belonging flows to members from the

consideration each member feels by being included in the work of the whole category. If a particular individual begins to be perceived to be the leader of the collective, through emotional contagion (

Hazy & Boyatzis, 2015;

Hazy & Wolenski, 2018), that individual may be called charismatic, as the shared experience of charisma from the combined effects of completion and closure spreads through the organization.

Taken together, universal properties suggest that an individual’s self-concept must be redefined to be an object along a path of idealized influence. This begins with an initial “abstract but unspecified leadership influence” object, or “limit”, that is assumed to be present, and is not actually associated with a particular individual agent or “leader”. It ends at the “disjoint union” of all of the influence in the category on those who are being led, that is, the terminal object or “colimit” determines who is included in “us” and who is not. The self-concept as an object of each member must map into the category structure, including the colimit, such that each individual’s self-concept as an object reflects the idealized influence of leadership on the whole CUPInfluence. Note that a profound redefinition of self from a discrete self-concept to an embedded self-concept reduces cognitive load, but this reduction may or may not be efficacious. It requires the self-concept to simultaneously accept idealized influence and conform to specific participation requirements that are inherent in the contagion of generalized influence falling on others in the collective. This means that accepting influence also requires being part of and conforming to the norms of the community. This redefinition is indeed self-transcendent; it is at once definitively linked to both the shepherd (limit) and the sheep (colimit).

For each member that projects their self-concept as an object into CUPInfluence, cognitive load is reduced via the assignment of semantic truth to idealized influence and contagious participation in a collective representation closed to universal properties. It is not difficult to imagine how this redefinition of self-concept as an object might be experienced as “charisma”. If a “leader” is perceived to be triggering the experience, perhaps by attracting the attention of members or articulating a vision of the future, that individual might be said to be charismatic. However, accepting generalized leadership influence, due only to the experience of “charisma”, that actually derives from the limit universal property of the CUPInfluence, on the one hand, and the surrendering of a portion of one’s autonomy to become part of a whole, its colimit, on the other, may involve unstated costs that each individual should consider when accounting for net benefits. Costs have consequences and carry risks with them. The next section suggests how one might engage in this accounting and mitigate these risks, but first, an illustrative category example.

3.5.2. Illustrative Category Example #5: A Simple Representation of the Charisma Phenomenon

From a practical perspective, choices by individuals are being influenced, in part, by choosing to accept influence and imitate the choices of other individuals, who might be called or tagged as leaders. In computational modeling studies, the influence of these leader-tagged agents on other agents are represented as dyadic elements of a “leadership influence process” representation (

Hazy & Mahmoodi, 2024). By imitating a leader-tagged other, an individual agent is implicitly assuming that this dyadic representation can be assigned semantic truth. By doing this, individual agents, as followers, effectively give up a measure of individual autonomy to participate in the broader collective category. This higher-level categorical representation describes how a given individual accepts the influence structures described within a categorical representation. As shown in

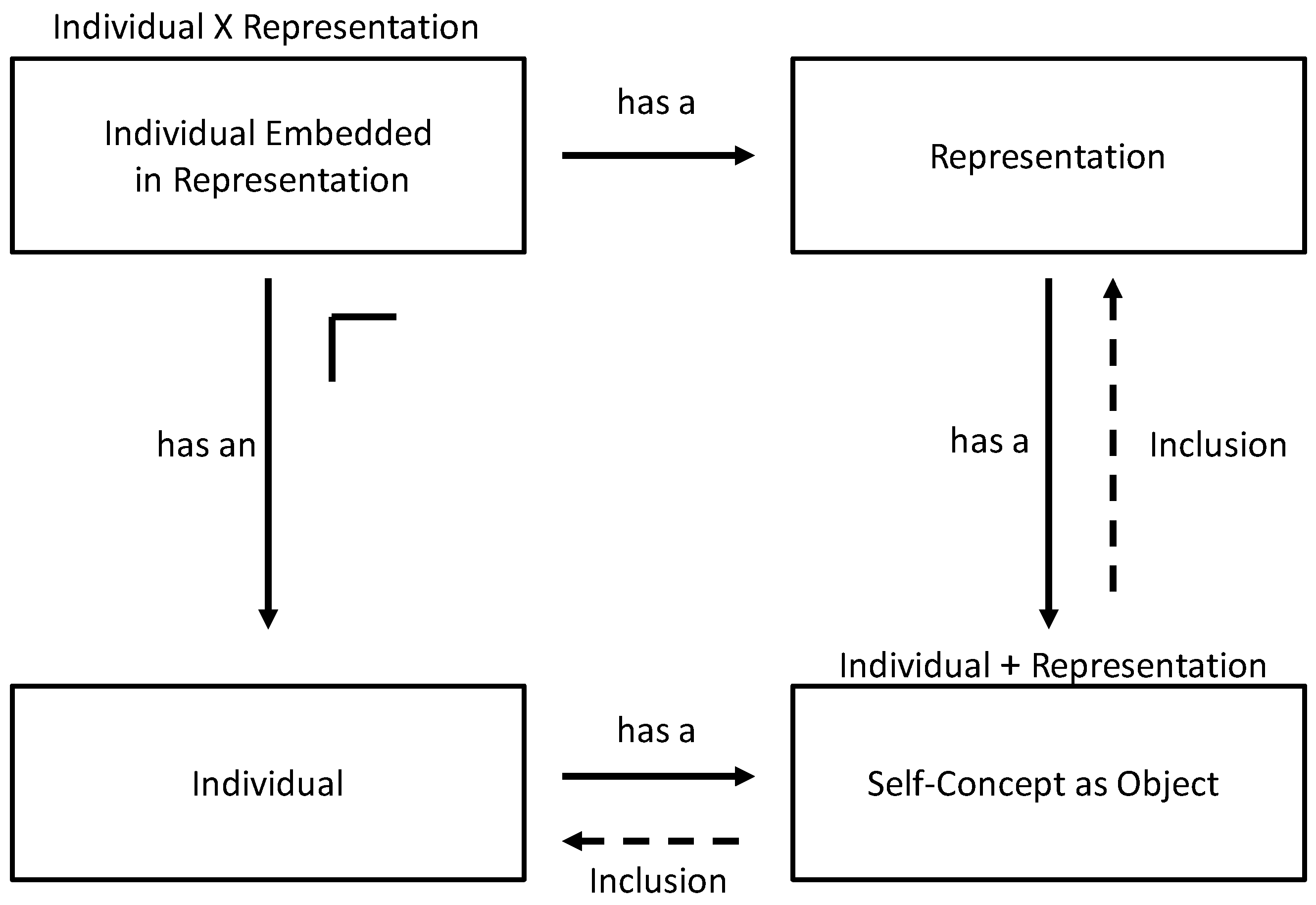

Figure 1, this article asserts that the charisma inducing-experience occurs by mapping one’s discrete self-concept into a category that includes two elements, the discrete self-concept and

CUPInfluence, which includes the same self-concept as a member.

Figure 1 shows that this higher-level structural category has only two objects: first, a representation of the internal structure of the collective community, for example, as represented by

CUPInfluence, and second, the self-concept of the focal individual agent. In addition to defining the other requisite properties, that is, an identity map, composition, and associativity, an additional morphism is defined that maps the focal individual’s self-concept as an object into the representation as a participating individual embedded as a self-concept in the representation.

Finally, the category in

Figure 1 is assumed to be complete and closed by adding the limit and colimit, which are posited to be actualized as idealized influence from the limit of

CUPInfluence and inclusion, and belonging as a member that is mapped to the colimit in

CUPInfluence. As other agents copy the influence process of a particular leader-tagged individual to multiple other leader–follower dyads through contagion dynamics, the logic of the overall abstract representation can reasonably be assumed to include the assignment of semantic truth to whatever that representation includes.

As described in

Figure 1, to accomplish this redefinition, events and other agents who do not accept the representation, are, and in fact must be, excluded from the abstract representation of the category, that is, one’s definition of self-concept in the context of the collective’s categorical representation of events must be equivalent regardless of the path taken to move from the representation of events to the definition of self-concept, which enables the commutative property as described in

Figure 1 to hold. For this to occur in all cases, non-believers must be excluded from the overall categorical representation. This is the only way that each member can assume that the representation is true for all agents that remain included in the representation. However, this belief may or may not be accurate.

3.6. Categorical Representations, Shared Mental Models, and the Charismatic Experience

Next, I return to the hypothesized connection between category theoretic representations of the leadership influence process in social networks and organizing systems, and how these might relate to the charismatic leadership described by social theorists. The literature on charismatic leadership goes as far back as

Weber (

1947), who described charismatic leadership as an individual personality characteristic that enables certain individuals to exert control over others in an almost supernatural manner. I begin by building on the self-concept approach introduced by (

Shamir, 1992;

Shamir et al., 1993). He identifies the genesis of a charismatic experience in a self-transcendent change within the followers’ definition of their self-concept.

To explore this idea, in this article I assume that the position of an individual’s self-concept in the context of others is implicitly represented within each individual’s mental model (

Sims, 2018) of their relational events. I also make the novel assumption that this model can be externalized, generalized, and represented (implicitly) as a mathematical category (

Mac Lane, 1978). Furthermore, I posit that when individuals share their representations, whether formally or informally, sometimes a shared mental model (SMM) emerges that unites a collective in a common perspective. The importance of SMMs as drivers of the leadership influence process has been studied in detail using computational modeling and, in particular, in agent-based modeling (ABM) studies (for a recent review, see

Hazy & Mahmoodi, 2024).

The argument put forward in this article is that category theoretic mathematics, as reflected and shared as an SMM in the memories of individuals, can be used as a surrogate for understanding the higher-level cognitive processes that have evolved in human beings. The premise is that mental processes use SMMs to assign attention to certain events, and focus intention toward certain outcomes during collective activities (

Ranganath, 2024). In particular, the models define conceptual objects, include the self-concept, determine relationships among the objects, and then use this framing to make choices and to act both individually and collectively (

Tomasello, 2014).

Thus, this paper contributes to leadership research by showing how the positive subjective experiences that result from framing SMMs of external events can usefully be described and studied using the mathematics of category theory (

Mac Lane, 1978;

Spivak, 2014). The use of mathematics in this context, I argue, has the potential to help distinguish between charismatic experiences that objectively might be explanatory and thus positive in terms of ensuing outcomes, and those that may be ephemeral and might ultimately lead to negative outcomes.

By doing so, this paper identifies what might be a previously unidentified socially generated cognitive bias, and one that can lead to fitness pitfalls that result from using a simplifying heuristic: the choice to accept social influence from others. More specifically, this paper argues that the cognitive bias associated with accepting an SMM associated with a charismatic leadership experience that is emotionally satisfying could have been avoided if an explicit category theoretic representation of relevant events had been consciously adopted rather than simply accepted for the emotional benefits (the “sugar high”) of a charismatic experience. As an example, the inclusion of universal properties in the representation may have required that many individual perspectives, and as a result their skeptical voices, may also have been excluded from the analysis. In these cases, the implicit nature of the charisma bias could lead to poor choices by followers with respect to their own self-interest, as well as the interests of others who were excluded. This realization could make a significant difference in organizational settings where effective leadership and followership are most consequential.

3.7. Venture Team—Scenario #4

In the venture team example, the two distinct and yet complementary categorical information structures may be exerting influence across the eight-member team. These are the visionary influence structure and the technology platform influence structure. Depending on the locally enacted leadership influence process (

Hazy & Mahmoodi, 2024), these might eventually be replaced by a single representation or SMM. There are three possibilities.

In the first possibility, due to the charisma experiences generated by the visionary representation or SMM, the practical disciplines of technology platform representation might begin to lose their influence as the visionary SMM begins to dominate. To amplify the influence of the visionary representation, the visionary entrepreneur might imply the inclusion universal properties of completeness (limit) and closure (colimit), for example, that “we” have a large a growing market opportunity (limit) and nothing, including no technology hurdles or limitations, can stop “us” (colimit). In this context, the influence of the technical team will be diminished. Perhaps these members might even be called complainers or nonbelievers, or perhaps even considered irrelevant. Members of the technical team might be excluded from discourse, left to work on their own, or even removed from the team or outsourced. Although this can succeed, one would expect that overcommitments and unexpected technology challenges might harm the venture.

The second possibility is that the influence of the technology-platform-focused representation or SMM might begin to dominate and eventually overwhelm the influence of the visionary representation. In this case, the technology platform representation might gain universal properties in order to fully realize the idealized influence of the SMM by including completeness and closure that might assume that “we” are the top technologists in “our” specialties (limit), all of “us” are critical to “our” technical and practical success (colimit). The group then would adopt a technology-dominated SMM, diminishing the contributions of the other members, such as marketing professionals or design experts. Although this approach may ultimately succeed, the risk is perhaps a short-sighted vision that misses opportunities.

The third possibility is that both of these representations coexist and are synthesized into a representation that includes both types of idealized influence. The challenge in this case is to create an SMM wherein “we” have both a large and growing opportunity and the technology skills to build the products and services that make all of “us” proud. From the perspective of the followers who remain on the venture team, each individual is left to either accept the redefinition of self-concept in the context of the surviving SMM and benefit from the charisma experience that results, or to be an outsider, become a consultant, or leave the organization.

4. Implicit Closed Representations and Leadership: Eight Propositions

Thus far, the discussion of mathematical category theory has mostly been syntactic, such that the implications that arise from representations are abstract and mathematical. However, such analysis has instrumental usefulness only when it is applied to observed events, such that the semantic truth of the information encoded in syntax is tested. So, what happens if in addition to the syntactic analysis in the previous section, the above CUPInfluence representation also maps to an abstract representation that gives rise to leadership influence in a separate representation, say an SMM of real-world objects such as team members, planned tasks, or operational objectives? Furthermore, what if the SMM is also assigned the semantic value “true” through empirical testing?

When both of these conditions are met, the representation can be taken to reflect a true state of the environment based on observed events. This semantic assignment implies that the syntactic truth value of the representation also implies that its predicted events are also semantically true (

Partee et al., 1990, p. 101). This is why an individual considers the sunrise a fact even if it is not observed. Thus, it is critical to test empirically and independently the semantic truth of the key premises of the representation, as well as all of their mathematical derivations, so that semantic truth can be assigned appropriately to each.

Thus, if the influence of one individual on another is assumed to be true in a representation of events, then this individual would likewise be assumed to influence the self-concept within the events being represented. The discrete self-concept disappears in the context of semantic truth, and the self-concept is redefined as a self-transcendent object that exists in the context of influence from other individuals who are also included in the representation. Since this change in self-concept is, in effect, a cognitive response that results from learning, it seems reasonable that it would be accompanied by an emotional response that reinforces this redefinition of the self-concept in the context of the follower being included in a leader/follower dyad. This discussion implies the following proposition:

Proposition 1. An individual who reports the adoption of a new generalized representation of events that has greater explanatory value than a prior representation, and also reports a redefinition of self-concept as an object in the context of this new representation, is likely to have a positive affective response, herein called “charism”, that is similar to reinforcement learning.

A representation that is assigned the semantic value “true” reduces cognitive load by eliminating perceived uncertainty. If the representation also suggests a heuristic that simplifies decision making by approximating the details of the representation, the cognitive load may be further reduced. However, the use of a heuristic has implications when the details of the heuristic are not aligned with those of the complete representation (

Kahneman, 2011). This creates the potential for error and increases the risk that by using a heuristic one can bias one’s choices and behaviors toward poor or uninformed decisions.

This proposition, if supported empirically, has consequences. It is the first of eight propositions that, if all are supported empirically, taken together describe the underlying behavioral dynamics that enable the leadership influence process, including the phenomenon of charisma.

Table 1 described the long-term four-step research agenda that will test in sequence the eight propositions averred in this article.

4.1. The Value of Category Theoretic Representation

The history of science, combined with the history of mathematics, has demonstrated that it is useful to construct mathematical categories with universal properties like limits and colimits. This is because categories with universal properties offer profound mathematical implications, such as differential calculus (

Mac Lane, 1978;

Goldblatt, 2006;

Spivak, 2014). For the most part, specific connections with fields of mathematics are beyond the scope of this conceptual article. In short, however, complete and closed categories have definitional structures that have been explored for centuries by mathematicians whose labors have explicated their very deep and nuanced syntactic structures in ways that offer rich deductive clarity. When a closed representation is assumed to be “true” semantically, many other internal relationships can also be presumed to be true by implication. Bridges are built to last for centuries and airplanes are designed to fly for decades based upon some of these deductive results. But in each instance, the representation must also be tested empirically to verify that the assignment of semantic truth to the premises was warranted and, perhaps more to the point, to verify that the syntactic truths that are implied in the representation do in fact also suggest that semantic truth naturally follows.

This clarity of thinking, enabled by category theoretic representations, combined with the deductive certainty that has survived the consensus of experts over many generations, implies that rigorous thinking in mathematical categories can be a useful tool with which to inform higher-order thinking more generally. Further, these representations can be usefully shared, stored, accessed, and used to test difficult and complex ideas that have been developed over many lifetimes. The history of mathematical reasoning provides security of thought, a kind of zone-of-cognitive-safety

2 that has survived and served humanity for millennia. This discussion suggests the following proposition:

Proposition 2. If category theoretic analysis is used to test the syntactic validity and semantic truth value of a representation of events and what it implies, then there is reduced heuristic risk in adopting it as well as the redefinition of self-concept as an object that adoption requires.

4.2. The Experience of Charisma Revisited

At the intuitive level, category theory describes how human beings can switch their cognitive framework from one abstract representation, sometimes called an SMM by leadership researchers (

Hazy & Mahmoodi, 2024), to another. When doing so by generalization (

Sims, 2018), one hopes to be able to infer what is true in the latter case because one believes that it was semantically true in the former case, even though one has never encountered the situation before. When one travels from one situation to another, for example, from New York to Chicago, one knows to stop at a red light and to go at a green light. Implicitly, this is because the New York traffic system is one instance of a larger-scale US public safety schema and the Chicago traffic system is another instance of the same US public safety schema. As a result, one can generally assume how other people will act in either context.

4.2.1. Adopting a New Definition of Self-Concept in a New Representation of Events

What is less intuitive, and often unspoken, however, is why one, whose self-concept includes being a New Yorker, is so easily able to “include” one’s self-concept into the Chicago instance of the US traffic planning schema despite having never been to Chicago. To make this generalization, the traveler must redefine the self-concept as an object of “a sometime-Chicagoan” within this new instance, thus abandoning for a time the “localized New Yorker” aspect of the self-concept. The act of fitting into a representation brings with it a sense of the familiar, of being at home again, but also of leaving something behind, an experience, I argue, akin to charism or rebirth.

This argument suggests that the individual described would experience six of the seven factors that

Shamir et al. (

1993) identified as characterizing the self-concept: “heighted self-esteem, heighted self-worth, increased self-efficacy, increased collective efficacy, …, social identification, and value internalization” (p. 581). To have this experience, however, the individual must engage in a translation of the self from one context to another, even if only temporarily. This suggests the following proposition:

Proposition 3. If an individual reports agreement with a representation that includes a universal property and also acknowledges a redefinition of the self-concept as an object in the context of the new representation that at the same time excludes some others, then that individual is likely to report heighted self-esteem, heighted self-worth, increased self-efficacy, increased collective efficacy, social identification, and value internalization in the context of that representation.

If another individual is associated with enabling this change in the self-concept, then the seventh factor identified by

Shamir et al. (

1993), “personal identification with a leader” (p. 581), is likely. This suggests the following further proposition:

Proposition 4. If the conditions in Proposition 3 are met and if that individual also acknowledges that the relevant representation being adopted was promoted by another individual, then that other individual is likely to be said to have “charisma”.

4.2.2. The Germ of Charisma

A redefinition of self is assumed to occur for an individual when that individual constructs or adopts a new representation of reality, and where in the process of changing the representation the individual also changes how the self-concept is represented in the context of the new representation. For example, redefinition might involve changing what had been a discrete representation of self-concept into a representation where the self is redefined in relationship to some universal property that is more explanatory.

More specifically, a discrete self-concept as an object isolated in a population can become a self-transcendent object when the self-concept as an object is redefined as an instance of a representation defined by relationships, such as task assignments, in an SMM. The new self might be defined in relation to a category identified as “us”, that is, the self-concept is now defined as a new self-concept that is a member of a closed category. The discrete self-concept is replaced by the community member self-concept. This self-transcendence of one’s self-concept into a more explanatory representation might, for example, simplify the tasks of focusing attention and taking an action by classifying others as either “us” or “them”, that is, included or not included in the category. As shown in