Abstract

Employee task performance plays a critical role in driving organizational success, and understanding its interaction with employee psychological status is essential for unlocking a workforce’s full potential. Psychological ownership has been shown to significantly influence performance outcomes, making it crucial to explore how these dynamics shape individual effectiveness. This study attempts to gain a deeper understanding of how employees’ sense of ownership influences their intrapreneurial behavior and contributes to enhanced task performance outcomes within organizational settings. A sample of full-time employees based in the United States provided 523 responses on an online questionnaire. The hypotheses were tested using SmartPLS. The findings support that intrapreneurial behavior exhibits full mediation of task performance’s relationship with psychological ownership. The outcomes indicate that when employees feel a sense of personal responsibility and attachment to their work, it significantly fosters their innovative actions and enhances their performance, thereby contributing to organizational success. This study contributes to the existing literature by arguing that employees who feel attached to the organization take more responsibility, improve performance, and proactively establish creative innovations to foster organizational success. Study limitations and recommendations are discussed.

1. Introduction

Employees’ behavior and attitudes within an organization are highly instrumental to its efficiency and, thus, its competitiveness (Nasifoglu Elidemir et al., 2020). Employee job performance defines the effectiveness and efficiency of individuals in meeting their assigned work roles and responsibilities (Van Scotter & Motowidlo, 1996) and is characterized as contextual or task performance (Coleman & Borman, 2000). The dimension of “task performance” (TP) covers activities undertaken by employees as part of their job description, participating directly in organizational productivity (Coleman & Borman, 2000). There is a widely held view that employee work performance actively influences teams, departments, and organization’s productivity, efficiency, and overall effectiveness (Carpini et al., 2017). Consequently, organizations are interested in the factors of enhancing their human assets abilities (Meijerink et al., 2022).

Employees’ psychological attachments to an organization can also cause both behavioral and attitudinal consequences, facilitating a continuous association with that organization (Pierce et al., 2001). Employees’ perception of “psychological ownership” (PO) is central to their relationships within and with their workplace and inculcates enhanced responsibility and commitment (Pierce et al., 1991; Van Dyne & Pierce, 2004). This results in improved TP and accountability, contributing directly to the organization’s success (Md-Sidin et al., 2009; L. Wang et al., 2019). PO is defined as a state in which individuals feel the ownership target belongs to them besides allowing the expansion of one’s self-view to include the object of ownership (Pierce et al., 2003; Van Dyne & Pierce, 2004). Employees’ feelings of ownership of the organizations in which they work can be overwhelmingly positive for those organizations (Dawkins et al., 2017). Distinct from other attachment-related variables (e.g., organizational commitment and organizational identification), the unique attribute of PO is the feeling of possessiveness; hence, employees feel that the organization is in some way their own (Pierce et al., 2003).

Intrapreneurship has gained significant interest in scientific research and business practices. Its importance has increased lately, given its demonstrable role in innovation, performance, competitiveness, and returns (Galván-Vela et al., 2021; Hernández-Perlines et al., 2022). Firms desire to foster “intrapreneurial behavior” (IB) and more efficacious IB decision-making internally to improve competitiveness (Melović et al., 2022). IB has been found to stimulate sustainable growth, reflecting the need to align economic with socio-environmental objectives (Méndez-Picazo et al., 2021). Pinchot and Soltanifar’s (2021) pioneering explanation of “intrapreneurship” refers to it as entrepreneurship by individuals “within” existing organizations. It pertains to the role of employees who contribute to creating innovations of any kind within an organization (J. De Jong & Wennekers, 2008). The entrepreneurship literature usually distinguishes between IB and “corporate entrepreneurship”, which are bottom-up and top-down phenomena (i.e., driven by employees or management), respectively (J. P. J. De Jong et al., 2015). IB is a key element of effective employee performance since the current business environment lacks predictability, making high levels of adaptivity and proactivity necessary (Covin et al., 2020; Griffin et al., 2007; Ritala et al., 2021).

Recently, there has been an increase in studies that link PO with organizational benefits, such as employee attitudes and behavior in the workplace (Zhang et al., 2021); however, only a few studies considered the possibility that the feeling of ownership may catalyze employees’ desires to improve their own performance (Dawkins et al., 2017). The diverse findings of existing studies range from PO encouraging employees to improve their performance (Brown et al., 2014; Van Dyne & Pierce, 2004) to findings indicating no significant effects (Mayhew et al., 2007). Such divergent outcomes highlight that the relationship between PO and TP has not been definitively recognized, and there is still a need for further investigation.

The reviewed PO literature demonstrates that the effect of PO on IB and TP is understudied (Atatsi et al., 2021; Prasetyo & Napitupulu, 2019). This is quite interesting because previous research on organizational behavior suggests that innovation and creativity are important factors (in addition to PO) in terms of whether employees participate in entrepreneurship (Avey et al., 2009; Van Dyne & Pierce, 2004). Recently, IB was acknowledged to have a positive relationship with organizational performance (Fellnhofer et al., 2016), consequently leading to a research focus on characteristics and demographic variables that differentiate intrapreneurs and other employees (e.g., Huang et al., 2021; Neessen et al., 2019) to help them maintain competitive performance. However, few researchers have examined the possible effect of IB on employee work performance (Mahmoud et al., 2022). Moreover, PO is very poorly understood in terms of its impacts and relations with other variables in organizational outcomes (Dawkins et al., 2017; Feldermann & Hiebl, 2022). Thus, examining the mediating mechanisms within an organizational context is vital and contributes to the theoretical fields of PO. A review of the existing literature proposes that IB and PO are a current and central issue (Alghamdi & Badawi, 2023; Batool et al., 2023; Gawke et al., 2018; L. Wang et al., 2019); however, the mediating role of IB in the relationship between PO and TP is under-explored (Prasetyo & Napitupulu, 2019).

These gaps in the literature may hinder our understanding of concepts and minimize their practical applications. Accordingly, this study aims to examine the mediating role of IB in the relationship between PO and TP. The central research questions guiding this study are the following: (1) Does employees’ sense of PO influence their TP within organizational settings? (2) Does IB mediate the relationship between PO and employee TP? We answer these by combining the PO theory (Van Dyne & Pierce, 2004) and self-verification theory (SVT) (W. B. Swann & Buhrmester, 2012; W. Swann & Pelham, 2002) to explain that employee IB mediates the relationship between PO and TP.

PO theory suggests that PO’s sense of possessing tangible or intangible objects cultivates feelings of efficacy. This feeling of efficacy is reflected in one’s belief in their competencies and capabilities (Dawkins et al., 2017; Pierce et al., 1991). As such, feeling like an organization owner might result in positive self-views of being a capable intrapreneur or innovator. For instance, employees who foster a high level of PO feel as though they are the organization’s owners. This mindset means taking full responsibility and accountability for decisions regarding organizational destiny as well as proactively embracing risks when choosing innovative opportunities that may enhance the growth of the organization. In the entrepreneurship literature, this is referred to as “entrepreneurial self-efficacy”, which refers to employees’ self-directed drive and capability to engage in entrepreneurial activities effectively (Zhao et al., 2005).

While PO theory suggests that employees who feel like owners will develop positive self-views of themselves as capable intrapreneurs, it falls short of explaining how feelings as business owners might evolve into improving TP. We, therefore, turn to SVT which proposes that individuals are driven to confirm their self-views, desiring others to perceive them as they see themselves (Shepherd & Haynie, 2011; W. Swann, 1982). Thus, while we draw from PO theory to suggest that feeling ownership elicits positive self-views of being a skilled intrapreneur, we further theorize that the development of these positive self-views will motivate employees to self-verify their ability to innovate and make calculated risks by fulfilling regular work role requirements outstandingly.

We therefore theorize that employees with high levels of PO will also show high levels of IB and TP. As such, they will be able to verify their self-views (as intrapreneurs) and signal to themselves and others that they are indeed capable of improving their TP, specifically in a highly competitive employment environment. This need for self-verification is considered a significant source of human behavior since individuals are motivated to take action to confirm their self-views. These two theoretical aspects allow us to provide a comprehensive understanding of motivation and behavior in the workplace.

This study contributes to the PO literature by showing how PO can improve employees’ performance. Several studies have demonstrated the positive effect of PO on employee work behavior and attitude (Hao et al., 2024; Van Dyne & Pierce, 2004; Zhang et al., 2021), and we add to the limited literature on the mechanisms of PO encouraging employee TP through IB as a novel mediator. The only study specifically found to relate PO to entrepreneurship was by Hamrick et al. (2024), who found that PO can enhance employees’ performance, while simultaneously (and counter-productively) inspiring them to leave the organization and start their own venture. Conversely, we claim that while PO can boost entrepreneurial intentions, this is more likely to be directed to the organization’s benefit, as employees, in exhibiting IB, are ipso facto already attached to it emotionally.

This claim adds to the PO literature (Avey et al., 2009) by considering IB to be a pro-organizational behavioral outcome. Furthermore, this study identifies PO as an antecedent of IB, supporting the claim that employee IB is an effective way to evaluate their belongingness (Sieger et al., 2013). The findings indicate that improved IB can arise from employees’ accruing an ownership ideation concerning the organization in which they operate. This posits that PO is a significant driver of IB. The interdisciplinary research strategy utilized in this research contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of such complex phenomena. Besides integrating the PO and SVT theoretical paradigms, we can offer a better insight into how PO influences IB and, in turn, affects TP.

The next sections explain the study’s theoretical background, supporting theories, and applied methodology used to derive theoretical and empirical implications, followed by the results and discussion.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Psychological Ownership

PO is defined as “a state in which individuals feel as though the target of ownership (or a piece of that target) is theirs”(Pierce et al., 2003). PO reflects an affective and cognitive belief employees feel toward their organizations, which can be overwhelmingly positive for those organizations. Because employees consider their organization to be part of their self-identities (Belk, 1988), they develop positive attitudes toward it (Van Dyne & Pierce, 2004). PO is distinguished from other forms of attachment in that it is not based on relational processes such as those formed during interpersonal interaction and social exchange (Dawkins et al., 2017), but instead is an identity-based process and forms the basis of employees’ organizational membership (Pierce et al., 2003). The appeal of the concept has continually increased in studies of organizational behavior and human resource management (Avey et al., 2009; Batool et al., 2023). In this study, we mainly focus on PO directed at the organization, as previous studies demonstrate that organization-based PO is a stronger predictor of key employee attitudes than job-based PO (Dawkins et al., 2017).

Prior studies have demonstrated that PO has an explanatory power in predicting employees’ performance (Zhang et al., 2021). Scholars have explained the PO motivation as it infuses self-efficacy, a sense of belongingness, and attaining self-identity (Pierce et al., 2003). The fulfillment of such needs explains why employees who develop possessive feelings toward their organizations are stimulated by this PO to present affect-driven behaviors, such as TP and OCBs (Dawkins et al., 2017).

2.2. Task Performance

Job performance defines employee’s task achievement and role fulfillment (Van Scotter & Motowidlo, 1996). Researchers categorize job performance as contextual or TP, the latter of which consists of all employees’ activities included in the conventional expectations of their role in relation to organizational productivity (Coleman & Borman, 2000). Growing research has examined the positive effects of PO on employee attitudes, motivation, and behavior in performing given tasks (Pierce et al., 2001), finding that PO is associated with organizational citizenship behaviors (Van Dyne & Pierce, 2004), affective commitment (Avey et al., 2009), job satisfaction (Avey et al., 2012), openness to changes (Liu et al., 2019), as well as reduced workplace deviance (Dawkins et al., 2017).

3. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

3.1. Psychological Ownership and Task Performance

The psychological attitudes of employees could positively maintain these behaviors as researchers explain that the main components of PO are autonomy (Mumford et al., 2002) and self-efficacy (Tierney & Farmer, 2011), which inspire individuals with higher levels of PO to create more organizational outcomes. Distinct “promotive” and “preventative” forms of PO were suggested by Avey et al. (2009), who conceptualized PO based on regulatory focus theory, which proposes that there are two self-regulatory systems in individuals (Higgins, 1997, 1998).

Promotive self-regulation relates to accomplishments and is concerned with fulfilling aspirations, which may lead to a willingness to take risks. It comprises four dimensions necessary to motivate development and improvement: self-efficacy, accountability, sense of belongingness, and self-identity. Employees with promotive PO are more willing to enhance their work performance when they perceive that this improved performance may benefit the organization because they perceive organizational enhancement as personally fulfilling (Avey et al., 2009).

On the other hand, the preventative self-regulation system is concerned with obligations and devises goals to reduce punishment. Employees with a preventative approach to PO may be less willing to modify the current performance because they seek to maintain the status quo and avoid change and risk potential to ensure predictability, stability, and safety; hence, they may experience anxiety regarding performing their jobs (Avey et al., 2009).

Although there has been increasing attention toward understanding the impacts of PO on employee performance (Mayhew et al., 2007; Van Dyne & Pierce, 2004; Wagner et al., 2003), studies have reached inconsistent findings. For example, Bai et al. (2024) examined the impact of job-based PO on innovative work behavior and job performance, but found no significant predictive influence. Similarly, Mayhew et al. (2007) found a non-significant relationship between organization and job-based PO and job performance. In contrast, a recent meta-analysis showed that PO can greatly increase employee performance relative to identification with and commitment to the organization (Zhang et al., 2021). A useful study of organization-based PO and supervisor-rated job performance demonstrated that its effect on job performance was marginally significant (Van Dyne & Pierce, 2004). Likewise, Brown et al. (2014) found a strong relationship between job-based PO and sales performance.

Such studies claim that PO motivates employees to generate innovative and original ideas for the organization’s benefit (Lee & Kim, 2021), and to put greater effort into their roles (Brown et al., 2014). Based on PO theory, we argue that employees who develop a sense of PO and themselves as “owners” perceive the target of ownership (organization) as part of their self-concept and, ultimately, their self-identities (Pierce et al., 2003). Hence, PO generates feelings of shared responsibility for the organization’s success. It motivates them to engage in behaviors that advance and protect the organization (TP) to sustain and enhance their consistent self-images as capable and skilled individuals. Such an argument is consistent with previous studies showing that PO encourages a sense of responsibility through extensive efforts that benefit the organization (C. H. Park et al., 2013) and demonstrating a positive influence of PO on performance (Han et al., 2015; Mustafa & Sim, 2022). Based on the previous discussion, we propose the following:

H1.

PO significantly and directly affects TP.

3.2. Psychological Ownership and Intrapreneurship Behavior

Organizations are interested in building a culture that promotes their strategic vision and encourages creativity to improve performance from the employee to the organization-wide level (Blanka, 2019; Giang & Dung, 2022; Maritz, 2010). Intrapreneurship is a bottom-up initiative by employees within an organization, taking the drive to start innovations without explicit agreement from top management to introduce new ideas for the company’s benefit (S. Park et al., 2014). Thus, researchers define IB as pursuing, evaluating, and exploiting innovative opportunities within an organizational context (Bae et al., 2014; Gielnik et al., 2017). These practices inspire a culture of creativity and promote individual innovation and entrepreneurship in organizations (Pinchot, 1985). The IB literature covers three commonly cited dimensions: being innovative, taking appropriate risks, and being proactive (J. P. J. De Jong et al., 2015), to which a recent study added behaviors of “strategic renewal” and “new business venturing” (Giang & Dung, 2022).

Researchers attempting to understand IB’s antecedents have demonstrated that combining individual and organizational factors facilitates entrepreneurial behavior in organizations. For example, instrumental organizational-level factors include management support, rewards, and organizational boundaries (Hornsby et al., 2002; Kuratko et al., 2005). Meanwhile, individual-level attributes have been recognized as dispositional traits, demographic characteristics, values, and attitudes (Blanka, 2019; Heinonen & Toivonen, 2008; Neessen et al., 2019). More recently, psychological states have been shown to affect entrepreneurial behavior (Sieger et al., 2013), suggesting that self-confidence and initiatives influence entrepreneurial behavior (Heinonen & Toivonen, 2008). However, the individual-level psychological antecedents of intrapreneurs still require more investigation (Dawkins et al., 2017; Mahmoud et al., 2022).

Employees’ feelings of ownership of the organization become an extension of their self-concept (Van Dyne & Pierce, 2004). This expansion of one’s self-concept can appear in the form of individuals’ positive beliefs in terms of their ability to control or influence the object of ownership (Dawkins et al., 2017). The concept of the “extended self” with regard to PO suggests the identification of employees with their organizations, whereby workers feel that the organization in which they work is aligned and to some degree integrated with their own sense of self. This imbues a continuum of self-identity that encompasses organizational activities and goals, whereby employees perceive that their own interests and goals are aligned with those of the organization and, consequently, work hard for themselves and ipso facto for the organization (Pierce et al., 2004).

This also relates to PO being associated with an increased sense of personal responsibility for the target of possession (Pierce & Jussila, 2011). Therefore, employees who experience a sense of PO will have intrinsic motivation and a feeling of responsibility toward their organization and will proactively assume responsibility for their work outcomes. Such employees may be more proactive in using available resources to improve their organization’s situation by voluntarily engaging in IB to develop and exploit business opportunities (Jussila et al., 2015). The feeling of responsibility implies that their perceptions of their roles will expand, making them more likely to move beyond the boundaries set by their actual roles (Prasetyo & Napitupulu, 2019) and promote their attitudes toward change (Pierce & Jussila, 2011).

Previous studies have also found that PO is significantly related to extra-role behavior (Mayhew et al., 2007; O’Driscoll et al., 2006). Employees who have high levels of PO engage in pro-organizational and collectivistic behaviors, seeking to attain organizational objectives such as profitability and growth (D.-S. Chung, 2019). This means that PO can motivate employees to engage in IB. In this regard, Mustafa et al. (2016) discussed the mechanisms by which PO motivates engaging in entrepreneurial behavior in business. First, ownership encourages a sense of personal responsibility towards the firm, resulting in employees’ need to express their care by presenting the willingness to nurture their firm. Moreover, PO inspires feelings of empowerment and autonomous leading in those who feel the ownership of the business has an impact on business actions and destiny. Finally, the ownership ability to inspire a sense of control leads those feeling high PO to feel the ability to control the environment. The self-efficacy theory explains this in terms of the control the employee feels over their ability to form the environment being conducive to a greater likelihood that they will participate in IB.

Also, this feeling of belongingness strengthens employees’ proprietary ideation and perceived responsibility towards their organization, which energizes them to participate in activities beyond the narrow scope of their formal and compulsory duties (i.e., IB) (Liu et al., 2019). Researchers have specifically noted that PO is positively related to innovation among employees in their behavior in the workplace (Y. W. Chung & Koo Moon, 2011; Woo et al., 2019). Feelings of ownership may also inspire positive evaluative judgments, promoting employees to reciprocate organizationally beneficent behaviors (Pierce et al., 2004), such as IB. It has been abundantly attested by previous studies that greater PO is associated with greater proactiveness among employees (Van Dyne & Pierce, 2004), including taking self-initiated, anticipatory actions (Parker et al., 2010; Wagner et al., 2003).

Despite the importance of PO as a positive attitude and IB as constructive workplace deviance, it has rarely been studied until very recently (Yıldız et al., 2015), and few researchers have examined the relationship between PO and IB (Giang & Dung, 2021; Mustafa et al., 2016). We propose that employees with more PO experience greater perceived responsibility for organizational activities (Pierce et al., 2004), and that this is associated with increased IB due to greater command over environmental resources and opportunities (Bandura, 1997). Such emotional states can ultimately result in IB and other proactive traits and activities (Spreitzer, 1995). Though these behaviors are beyond the scope of formal job definitions, they add value to organizations and help achieve organizational goals (Robbins & Galperin, 2010), due to the close alignment of the latter with employees’ own self-efficacy and needs, as discussed above (Zhao et al., 2005).

It should be noted that there are some potential drawbacks of PO, as demonstrated by numerous studies, such as an increased tendency to ignore ethical issues and engage in “pro-organizational” unethical behavior (e.g., employees bending or breaking the rules when this is perceived to be in the organization’s best interests) (Batool et al., 2023; Umphress et al., 2010; L. Wang et al., 2019; Xu & Lv, 2018). High levels of PO might push employees to engage in unethical behaviors in the interest of the organization whereas stronger feelings of ownership stimulate employees to hide knowledge from co-workers as they believe it is their target of ownership that belongs to them (Batool et al., 2023). Those employees with high PO would have stronger avoidance motivation by focusing on avoiding losses and protecting their ownership, leading them to display a stronger tendency to exhibit negative workplace behaviors such as territorial behavior and knowledge hiding (L. Wang et al., 2019). As PO is a double-edged sword, managers should be mindful and provide correct guidance for employees’ pro-organizational behaviors (Xu & Lv, 2018). On the other hand, W. Wang et al. (2024) claimed that PO induces an individual’s self-efficacy, which in turn enhances self-esteem and prevents the tendency to behave unethically.

However, we argue that IB can, in general, be considered a legitimate tool whereby employees can express their concerns to ensure the growth and survival of the organization (Hornsby et al., 2002; Kuratko et al., 2005). Our argument is based on the assumption that ownership motivates employee’s IB through its effect on feelings of empowerment and autonomy and their impact on company actions, decisions, and performance (Van Dyne & Pierce, 2004). A recent set of studies showed that employees who feel empowered are more likely to be creative and engage in entrepreneurial behavior (Alghamdi & Badawi, 2023; Bhatnagar, 2012).

As previously discussed, the promotive aspect of PO enhances performance; we argue that it also influences employee IB. Employees with strong feelings of organizational PO are more willing to move beyond the contract obligations and have a promotive focus concerned with fulfilling hopes to benefit the organization. They exhibit their care by increasing their willingness to take risks that are strategically aligned with the long-term objectives of the organization (Avey et al., 2009). Their accountability and motivation to improve the organizational outcome will balance caution with opportunity in a way that ultimately benefits the organization. Based on the previous discussion, we propose the following:

H2.

PO significantly and directly affects IB.

3.3. Intrapreneurship Behavior and Task Performance

IB can be seen as a vital source of organizational growth and success as it positively impacts both individual and organizational performance (Fellnhofer et al., 2016). The literature supports cultivating intrapreneurial environments related to higher profits and sales growth, improved performance, and increased employee satisfaction (Auer Antoncic & Antoncic, 2011). However, studies on the positive effect of IB on TP are lacking (Mahmoud et al., 2022).

When workers practice creativity and innovation, this positively extends their range of skills, thus influencing their performance (Geisler, 1993; Hayati & Caniago, 2012). For instance, Berisha et al. (2020) suggested that employees’ initiative to improve their work empowers them to be top performers. Where the unidimensional IB is the summation of risk taking, pro-activeness, and innovativeness (Mahmoud et al., 2020), it allows us to conceptualize IB as a vital resource for opportunity exploitation (Covin & Slevin, 1991) as well as for improving employee performance (Bakar et al., 2015; Mahmoud et al., 2018). The SVT regarding the motivational process allows us to argue that IB can positively relate to improved TP, as employees trying to verify their abilities to perform work outstandingly are likely to be more innovative and proactive intrapreneurs (Gawke et al., 2018). This premise allows them to position themselves as experts in meeting their work requirements, thereby permitting them to take calculated risks that can lead to organizational advantage.

Intrapreneurs think across different organizational units’ boundaries, which provides them with the ability to push creativity, the exchange of ideas and knowledge, and strategic renewal. They also act proactively in networks and establish relationships inside and outside the organization (Pinchot & Soltanifar, 2021). These skills and ties enable them to be open-minded and discover opportunities to enhance their TP. Also, scholars assume that IB contributes to a more resourceful work context (Mcfadzean et al., 2005) as well as to personal achievement. The self-initiated effort (innovation and opportunity exploitation) increases positive affect and energy at work. Such experiences may energize employees to handle work tasks more effectively (Gawke et al., 2018). Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H3.

IB significantly and directly affects TP.

3.4. Intrapreneurship Behavior Mediates Between PO and TP

PO is an extended self-feeling of the object of ownership, whereby employees develop self-views about themselves as business owners; they will strive to enhance their current performance to ensure continued self-verification. SVT suggests that effortful motivation for self-verification may have performance-enhancing effects (W. B. Swann & Buhrmester, 2012; W. Swann & Pelham, 2002). For instance, individuals try to demonstrate to themselves and others their ability to achieve high performance by allocating their energy and cognitive resources toward improving current work outcomes (Cable & Kay, 2012). Employees may feel interested in demonstrating their skills and competencies by engaging in IB to verify self-views and signal that they are proficient in performing better in their current work tasks, specifically considering the relativity of being described as a top performer in the employment context.

PO also relates to a sense of confidence in abilities and control, leading to employees setting higher expectations and aiming for superior goals (e.g., entrepreneurial projects), which leads to increased work effort. Reaching these goals successfully and being on top in performance confirms employees’ self-views (Bandura, 1997). Indeed, scholars propose that employees can increase their work performance levels by demonstrating their intrapreneurial skills, innovativeness, and proactiveness (J. P. J. De Jong et al., 2015; Newman et al., 2019). Individuals who feel confident in their abilities to identify new business opportunities, create new products, take risks, develop efficiencies, and think creatively should verify their ability to perform at higher levels and work to validate their efficacy beliefs. This is applied by recognizing that the achievement of long-term complex goals (e.g., being a top performer) requires the pursuit and attainment of intermediate goals (e.g., presenting IB abilities) that help individuals work toward a higher-order goal (such as TP) (Hom et al., 2012). Employees thus strive to prove their competence in unstable, unpredictable employment conditions.

Van Dyne and Pierce (2004) suggested that PO could enhance motivation and performance but should also be integrated with other organizational strategies. From a theoretical standpoint, their findings challenge some of the expectations set by earlier research, using a broader approach to enhance the performance rather than expecting a stronger, more direct impact on performance (Md-Sidin et al., 2009). Accordingly, scholars call for a re-evaluation of these assumptions, indicating that the dynamics of performance are more complex than what was previously proposed and calling for the exploration of how PO interacts with other variables and conditions in the workplace to influence performance. Scholars have argued that the relationship is “unlikely to be direct” and likely entails mediation in the connection (Van Dyne & Pierce, 2004). However, few researchers have explored possible mediating mechanisms between PO and performance outcomes (Feldermann & Hiebl, 2022). Accordingly, we suggest IB as one such mediating mechanism theorized to evolve from PO and help explain the link between PO and TP. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to examine the mediating role of IB in the relationship between PO and employee task performance.

The literature confirms the positive relationship between PO and innovation (D.-S. Chung, 2019), and entrepreneurial behavior in employees (Giang & Dung, 2021; Mustafa et al., 2016; Prasetyo & Napitupulu, 2019). For example, Giang and Dung (2021) examined job-based PO in nonfamily employees’ international intrapreneurship within family firms. Also, Prasetyo and Napitupulu (2019) found a relationship between PO and managers’ entrepreneurial behavior. This evidence was also replicated by Mustafa et al. (2016), who explained that the PO process affects the entrepreneurial behaviors of corporate middle managers through the mediating role of job satisfaction. Similarly, studies found that employee engagement in IB effectively increases their work performance (Ahmad et al., 2012; Berisha et al., 2020; Griffin et al., 2007; Leong & Rasli, 2014). Moreover, Hamrick et al. (2024) confirmed that PO indirectly affects job performance through entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Accordingly, we expect that IB could act as a mediator between PO and employee TP. For instance, employees who experience firm PO are predisposed to be more proactive in their organizational role, innovating and taking risks that generally improve performance (Atatsi et al., 2021). This study, therefore, assumes that IB has a mediating impact on the relationship between PO and TP.

H4.

IB mediates the relationship between PO and TP.

3.5. Research Model

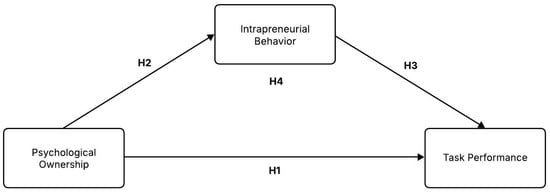

Based on the identified hypotheses derived from analyzing the existing literature, the research model employed in this study is exhibited in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research model.

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Sampling and Procedure

The target sample included working employees at companies in the USA. The study strategy deployed a quantitative questionnaire as the main data collection method, subject to subsequent statistical analysis. The unit of analysis was full-time employees currently working at different organizational levels. This study employed a non-probability sampling method, specifically convenience sampling. Due to the lack of access to a comprehensive employee database in the USA, a formal sampling frame could not be established. As a result, participants were selected based on their availability and willingness to participate. We recruited participants to voluntarily contribute to our study through a cloud research website, Prolific. This website is described as one of the two best online providers that offer high-quality data for questionnaires (Douglas et al., 2023). Further, an online survey link was sent to the targeted population, which was restricted to full-time employees with at least one year of organizational tenure. Following previous studies (Mayhew et al., 2007; Tsai, 2021), we did so to ensure that participants spent enough time with their current organization to express psychological relatedness. We also explored the sample profile by asking participants to answer questions regarding demographic characteristics such as gender, age, and work experience. Previous studies have shown that these demographic characteristics could influence an individual’s perception of ownership and their behavior (LePine & Van Dyne, 1998; W. Wang et al., 2024). After the listwise deletion procedure, 523 usable questionnaires out of 545 were used in the analysis due to the removal of responses with missing data or failed attention checks. The final sample comprised 57% males and 43.0% females, mostly holding a bachelor’s degree or higher. Also, 45.9% had 16 years or more of work experience, while 55.3% had worked with their company for six years. Table 1 presents the socio-demographic profile of the sample.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (N = 523).

4.2. Variables Measurement and Questionnaire Design

The structural equation model analysis considers two integral components: the evaluation of the measurement model and the structural model. The measurement model comprises validity analysis, where convergent and discriminant validity analyses are applied. Assessing the internal consistency of the measures was carried out by applying Cronbach’s alpha (α) and composite reliability (CR) analyses (Dijkstra & Henseler, 2015; Sarstedt et al., 2017). Moreover, the convergent validity of the measures was measured by the factor loading values and the average variance extracted (AVE) (J. J. Hair et al., 2014). Furthermore, for the assessment of discriminant validity, Fornell–Larcker criteria and Heterotrait–Monotrait ratio (HTMT) analyses were carried out.

The structural model evaluates the relationship between the variables and explains how these variables are related to each other (Coulacoglou & Saklofske, 2017). We used bootstrap sub-sampling for the bias-correction and confidence intervals of each model, alongside a 5000 bootstrap sub-sample technique, a non-parametric approach considered appropriate for normality violation with a non-normally distributed data set (Preacher & Hayes, 2008; Sarstedt et al., 2017; Streukens & Leroi-Werelds, 2016). Additionally, the direct and indirect effects of mediation were measured by the structural model.

A five-point Likert-type scale (with responses ranging from (1) “strongly disagree” to (5) “strongly agree”) was employed for participants to express their responses. All study measures were derived from the literature and had high Cronbach’s α scores and validity, as listed below with example items:

“Psychological Ownership” Measure: a seven-item scale developed by Van Dyne and Pierce (2004) (α = 0.91) (e.g., “I feel a very high degree of personal ownership for this organization”).

“Intrapreneurship Behavior” Measure: a fifteen-item scale developed by Stull (2005) (α = 0.93) (e.g., “In the course of my work, I generate useful new ideas”; “In the course of my work, I do things that have a chance of not working out”).

“Task Performance” Measure: a five-item scale developed by Koopmans et al. (2011) (α = 0.78) (e.g., “I always think about the results I must obtain’ and “I plan my work to finish it on time”).

“Attitude Toward the Color Blue” (ATCB) Measure: a seven-item scale developed by Miller and Simmering (2023) (α = 0.95). This marker variable evaluates the questionnaire’s Common Method Variance (CMV), which is a crucial statistical tool.

4.3. Common Method Bias Assessment

Both procedural and statistical methods were applied to control and reduce the potential CMV that might arise due to the nature of the data collection method (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Procedurally, participants were assured of the confidentiality of their participation and data anonymity, and two attention check questions and randomly ordered questionnaire items were used to minimize the possibility of artificial or deceptive responses by participants (Podsakoff et al., 2003; Salancik & Pfeffer, 1977). Statistically, the researcher added the marker variable ATCB (Miller & Simmering, 2023). As reported in the following section, there was no difference in the correlation between variables before and after ATCB was applied, either in value or significance. ATCB and other substantive variables had the lowest correlations and had no significant changes. To detect if variables were inflated, simple correlations were examined, and the correlations among the observable variables were within the acceptable range (Spector, 2006). These consistent findings, empirical evidence, theoretical argument, and previous research make it possible to dismiss any CMB concerns.

4.4. Statistical Procedure

Smart-PLS non-parametric methodology is considered an appropriate statistical tool for structural equation modeling (SEM). It can be applied to both exploratory and explanatory investigations and non-normally distributed data for both small and large sample sizes in predictive modeling (Latan et al., 2023). Smart-PLS modeling does not rely on the conventional approach fit indices used to obtain the model fit statistics, in contrast to covariance-based implementations. Analysis through Smart-PLS can be completed with a minimum sample size requirement, and it can operate on any N number of samples. In contrast to covariance-based SEM, Smart-PSL SEM works on a single-item construct for a formative indicator and a minimum three-item construct as a reflective measurement indicator in the modeling. Also, it is worth highlighting that PLS-SEM can operate with as few as ten items, and does not require a large sample size (D. X. Peng & Lai, 2012). In this study, we applied discriminant and convergent validity analyses, and the analysis results are reported as described in the following section.

5. Results

5.1. Overview

The means, standard deviations, correlations, and reliabilities, as well as the CMV correlation above the reliability for all variables, are displayed in Table 2. It is not surprising that a positive association was found between PO and IB (r = 0.43, p < 0.001) and TP (r = 0.18, p < 0.001). Also, IB was related to TP (r = 0.34, p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Pearson product-moment correlation analysis between study variables (N = 523).

5.2. Measurement Model Assessment

The outcomes confirmed that the internal consistency of the study variables was found to be appropriately fit, and the CR and α for all the variables were found within the acceptable range (>0.70–0.95, respectively) (Sarstedt et al., 2017). Furthermore, the AVE for all the variables was found to be acceptable except for the variable IB, whose AVE value was less than 0.50. However, the CR for IB was greater than 0.60, thus the convergent validity of the construct was still considered acceptable (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Moreover, the loadings on each factor were detected, and the results indicated that the value of factor loadings on each item was adequate (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Measurement properties of model 1 constructs (n = 523).

Moreover, the evaluation of the discriminant validity was carried out using Fornell–Larcker criteria (Table 4) and HTMT (Table 5), whereby the square root of the AVE for a specific construct should be greater than any of the correlations of this construct with other constructs. The outcomes of the Fornell–Larcker criteria (Table 4) showed that the square root of AVE (the values diagonally displayed in bold) was greater than the value of the correlation between the variables, confirming that the criteria of discriminant validity of 0.80 were met, as recommended by statistical analysts, thus discriminant validity was supported (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Kline, 2023). These convergent and discriminant validity findings prove the measurement model’s construct validity. As suggested by Sarstedt et al. (2017), the value of the correlation should be less than 0.90. The HTMT results (Table 5) showed that the values of inter-construct correlation were found to be <1, indicating the discriminant validity of the measures used.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity of measures (Fornell–Larker criteria).

Table 5.

Heterotrait–monotrait criteria (HTMT) discriminant validity.

5.3. Structural Model

The structural model was evaluated, and the path between the direct, indirect, and interaction effects was observed for hypothesis testing and mediation. The analysis results are shown in Table 6 and Table 7.

Table 6.

Evaluation of structural model.

Table 7.

Estimate of the indirect path effect.

The structural model was tested by investigating the β, p-value, R2, f2, and Q2 estimates. Whereas β measures the strength of the relationship between the observed variables, R2 explains the overall predictability of the structural model (J. F. Hair et al., 2012). Additionally, the p-value signifies the significance level to determine whether a hypothesis is supported. In addition to looking at changes in R2, we considered f2, which represents the meaningfulness of the effect size of each predictor. Moreover, in SmartPLS, the blindfolding procedure helps to generate values of Q2, which applies a sample reuse technique that omits part of the data matrix and uses the model estimates to predict the omitted part. Studies recommend values of β above 0.20 (J. F. Hair et al., 2012) and R2 and f2 values above 0.13 and 0.15, respectively (J. F. Hair et al., 2012).

SEM based on Smart-PLS provides an estimate of the Q2, the index used to measure the predictive power of the models. Q2 shows how well the study model can forecast the result variables in the model based on the predictor factors. The authors propose that Q2 has a value between 0 and 1, whereby values nearer to 1 signify higher predictive significance, and values conversely nearer to 0 imply poorer predictive relevance. Additionally, the structural model’s predictive ability can be assessed using the R2, often referred to as the “coefficient of determination”, which combines the influence of exogenous (independent) variables on endogenous (dependent) variables (Tenenhaus et al., 2005). According to Sarstedt et al., the recommended values of R2 are classified according to their predictive power as follows: 0.25 “weak”, 0.50 “moderate”, and 0.75 “strong”.

Table 6 and Table 7 display the β, p-values, R2, f2, and Q2 of the hypothesized structural model. The β and R2 values were above the minimum threshold limit, and the p-values showed that all the model paths are significant except for the PO and TP. As for the f2, all the paths showed weak relationships (f2 = 0.07–0.09). Table 8 shows the Q2 values of the dependent constructs: Q2 (IB) = 0.27 and Q2(TP) = 0.12. All the Q2 values were above zero, providing support for the predictive relevance of the conceptual model (J. J. Hair et al., 2014). Based on the R2, f2, and Q2 estimates, the hypothesized model had reasonable explanatory power.

Table 8.

Predictive relevance and power of endogenous variables.

5.4. Hypothesis Testing

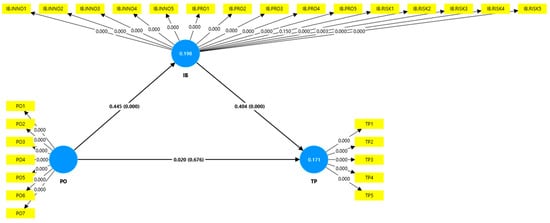

The analysis results of the direct effects (Table 6) revealed that PO was an insignificant predictor of TP (β = 0.02, t = 0.42 p < 0.68) rejecting H1. Moreover, PO was a significant predictor of IB (β = 0.45, t = 10.89, p < 0.001) accepting H2. Further, the analysis showed that IB was a significant predictor of TP (β = 0.40, t = 8.08, p < 0.001) accepting H3.

The mediation analysis results (Table 7) showed that IB mediates between PO and TP. The indirect relationship was significant (β = 0.18, t = 7.27, p < 0.001), accepting H4 and indicating a full mediation role of IB. Figure 2 displays the statistical model of mediation.

Figure 2.

The statistical model of mediation.

6. Discussion

6.1. Main Outcomes

The study proposed a mediating model to examine the effects of PO on TP. Utilizing PO theory (Van Dyne & Pierce, 2004) and the SVT (W. B. Swann & Buhrmester, 2012; W. Swann & Pelham, 2002), we hypothesized that IB would act as an explanatory mechanism that explains the relationship between employee psychological status and their behavior. More specifically, this paper tested the indirect relationship of PO on TP through IB. The results confirm all hypotheses except for the direct relationship between PO and TP, which was found to be insignificant, thus indicating the full mediation role of IB between PO and TP and successfully answering the research questions.

The outcomes of this research are contrary to our hypothesis of the direct impact of PO on TP, aligning with previous studies (Mayhew et al., 2007; Van Dyne & Pierce, 2004). The relatively scant amount of studies examining the impact of PO on TP provides contradictory results, indicating negligible or non-significant effects (Dawkins et al., 2017). To demonstrate our findings, they imply that employees feeling a sense of organizational ownership do not directly manifest this in improved TP efficiency. This could be explained by the limited variability among employees’ role performance because of role constraints. Therefore, PO could be less important in mandatory role requirements, but relevant to any volitional behavior, such as extra-role behaviors. Also, such findings suggest that external factors (e.g., socio-demographic characteristics and organizational support actions) may substantially affect TP.

The outcomes of our research affirm previous studies in demonstrating a significant impact of PO on IB (Giang & Dung, 2021; Mustafa et al., 2016). This indicates that employees who sense ownership over their organizations are more likely to be proactive in solving problems and improving outcomes, go beyond the minimum requirements, and seek innovative ways to achieve organizational success (O’Driscoll et al., 2006; Parker et al., 2010; Van Dyne & Pierce, 2004; Wagner et al., 2003). This finding challenges the belief that employee PO increases the possibility of exhibiting dysfunctional deviant behavior (Batool et al., 2023; Umphress et al., 2010; L. Wang et al., 2019; W. Wang et al., 2024; Xu & Lv, 2018).

This study also empirically examines the proposed conceptual model, arguing for the positive impact of IB on TP (Bakar et al., 2015; Mahmoud et al., 2018). The study found support for the positive direct impact of IB on TP, confirming a previous study (Mahmoud et al., 2022), and it extends the latter’s results by including employees at all levels. For instance, IB may assist in building a resourceful work environment where employees can engage in a self-directed learning and collaboration setting. This context enhances the sense of professional growth and increases positive feelings and energy at work. Such experiences energize employees to handle work tasks more effectively.

The most critical finding of this study is that PO indirectly affects TP only through IB. Employees with a high sense of ownership towards the firms in which they work are predisposed to undertake innovative behavior, being proactive and taking risks that ultimately benefit the firm, thus improving performance. For instance, PO does not directly enhance TP; instead, it motivates employees to engage in IB, while intrapreneurial action improves their performance. When employees feel a sense of PO over their organization, they are more likely to take proactive actions. Those individuals who are driven by a sense of responsibility and the motivation to improve organizational outcomes will assess potential risks and align them with the long-term firm objectives, aiming to gain a competitive advantage. PO encourages employees to demonstrate IB by taking initiative, strategically calculating risk, suggesting improvements, and tackling problems creatively. These behaviors improve their TP as employees become more invested in finding innovative ways to achieve better results.

However, Van Dyne and Pierce (2004) demonstrated that PO encourages helping behaviors. This finding suggests an alternative explanation where employees who feel a strong sense of ownership are more inclined to engage in voluntary and supportive actions that benefit both their coworkers and themselves by figuring out alternative solutions for challenges. Similarly, PO has also been shown to foster learning behaviors, as employees feel more personally invested in their growth and the acquisition of new skills that can contribute to their work performance (Dawkins et al., 2017). This aligns with the idea that PO encourages behaviors that extend beyond what is required in the job description. Also, employees who feel psychologically attached to their organization are often stimulated by a sense of responsibility and are willing to share their insights, expertise, and resources, which leads to improved collaboration. Thus, they contribute to knowledge-sharing and knowledge-receiving behaviors (Han et al., 2010). Since PO can encourage information sharing and the establishment of high-quality communications within the organization (Carberry et al., 2024), these behaviors are vital for improving decision-making processes and thus could enhance individual task performance.

6.2. Theoretical Implications

This paper has multiple theoretical contributions that shed light on possible explanations regarding the interplay between employee psychological status and TP. First, this paper contributes to the literature on PO and PO theory (Van Dyne & Pierce, 2004) by arguing for the influence of employee organization-based PO on their IB. Such influence is argued to benefit them by increasing their TP. Several studies have argued for the impact of PO in the workplace, yet few have investigated IB as an explanatory mechanism through which such an effect takes place (Hao et al., 2024; Mustafa & Sim, 2022; H. Peng & Pierce, 2015; Zhang et al., 2021). In other words, employees with high levels of PO not only feel attached to the organization and take responsibility, but they also proactively go beyond the formal work role expectations and establish creative innovations to foster organizational success (Prasetyo & Napitupulu, 2019).

Additionally, the current study adds to SVT (W. B. Swann & Buhrmester, 2012; W. Swann & Pelham, 2002) by exploring IB–employee TP issues. Simply put, intrapreneurs can enhance their work performance, since experiencing extensive business investigation allows them to gain novel skills that will later support their performance. Finally, this paper contributes to the employee work performance literature (Coleman & Borman, 2000; Koopmans et al., 2014) by examining the TP as a behavioral manifestation of IB. For instance, the study investigates TP as the outcome of interest employed by those who psychologically feel like the owners of an organization and those with high levels of IB.

6.3. Practical Implications

Our study has several implications for practice. Organizations are recommended to cultivate a sense of PO among their employees. In developing a work environment where employees can manifest a deep sense of responsibility and attachment to their work roles, the organization creates a productive workplace. For instance, employees are more likely to develop a sense of ownership when they understand their role in the organization and see how their work contributes to its success. Moreover, when employees are involved in setting their work goals as well as the organization’s goals, they take ownership of these goals and feel the responsibility for achieving them. Also, giving employees the freedom to choose how to approach tasks and challenges and take the initiative inspires innovative thinking and experimentation that contribute to the firm’s success.

Moreover, organizations should modify their leadership development programs to highlight an understanding of the role of empowering and involving team members. Leaders can be trained to foster a sense of ownership within their teams by involving members in problem-solving and process improvement initiatives. Leaders can also learn how to give their team members more autonomy, decision-making authority, and opportunities for innovation. This, in turn, can positively affect the relationship with co-workers and leadership and develop a deeper connection to their roles.

Since IB is the key mechanism linking PO to improved TP, organizations and managers should promote IB by giving employees the support, structure, and resources to verify their entrepreneurial self-views. Encouraging the freedom to propose new service offerings or operational strategies stimulates one to think like an entrepreneur and enables employees to respond quickly to challenges or opportunities. Hence, organizations that cultivate a sense of ownership and IB increase job satisfaction and performance results and reduce the likelihood of employees seeking other employment opportunities.

7. Conclusions, Limitations, and Recommendations for Future Research

Understanding the interplay between employee PO and their performance has recently become increasingly interesting for researchers. This growing interest reflects a broader recognition of the significant impact that PO can have on various organizational outcomes. In this study, we suggest that PO influences employees’ TP indirectly by inspiring IB through activities such as engaging in innovation practices, being proactive, and risk taking. Such experience expands employees’ mental and physical skills and abilities, allowing for better TP. PO encourages employees to perceive their work as an extension of themselves, motivating them to take greater initiative and demonstrate a heightened sense of responsibility; this heightened sense of ownership can catalyze IB. By engaging in related behaviors, employees lead to increased confidence and autonomy and broaden their knowledge base, which further supports employees’ ability to perform tasks efficiently and tackle challenges more effectively. Thus, psychological ownership enhances employees’ engagement and motivation and also indirectly influences their task performance by cultivating behaviors essential for success in dynamic and competitive environments.

Although our current work has several strengths, some limitations need further discussion. First, the data for this study were collected using a self-reported survey. This might present concerns about generalization, social desirability effects, and CMB (Podsakoff et al., 2003). However, self-reports for PO are considered more methodologically appropriate to explore this variable, as it is intrinsically meant to reflect individuals’ own personal insights and perceptions about themselves (e.g., rather than conventional productivity KPIs in actual work outcomes) (Van Dyne & Pierce, 2004; Zhao et al., 2005). Also, Fuller et al. (2016) suggested that studies using a single source of data are not necessarily predisposed to CMB. Another limitation regards the generalizability of the study findings. The use of convenience sampling may introduce sampling bias. The study’s sample may not be representative, restricting our ability to generalize the findings to the broader population.

A further limitation is that a cross-sectional study design was employed, whereby a snapshot view of a single time point’s data was used, which lacks longitudinal insights into hypothesized relationships over time (Bowen & Wiersema, 1999). Moreover, although this study shows that intrapreneurs function more efficaciously, in line with existing research (Berisha et al., 2020; Mahmoud et al., 2022), the relationship between IB and performance can be complex, and claiming the direction of causality must be undertaken cautiously (Gawke et al., 2018; Ritala et al., 2021). Future research is recommended to adopt a longitudinal design when re-examining the study’s relationships, with multi-time data collection (Ployhart & Vandenberg, 2010), to mitigate such limitations.

Second, it is worth noting that prior results examining the relationship between PO and performance have been inconsistent (Brown et al., 2014; Dawkins et al., 2017; Van Dyne & Pierce, 2004), which encourages an examination of the processes that mediate this relationship (Van Dyne & Pierce, 2004). This study sought to contribute to answering this call, finding support for IB as a mediating mechanism between PO and work performance. However, this proposed mediated model is open for an extension, and other moderating variables may be instrumental between PO and IB, as well as between IB and TP. For example, future studies can identify and introduce contextual factors, such as organizational cultures and leader entrepreneurial orientation.

Third, this study focused only on the positive consequences of PO. However, some studies conclude that PO may produce unfavorable behavior, such as knowledge hiding (Batool et al., 2023). Thus, there is a need for further research to investigate the predictive effect of PO on pro-organizational unethical behavior in depth.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.A.D. and N.S.B.; methodology, G.A.D. and N.S.B.; software, G.A.D.; validation, G.A.D.; formal analysis, G.A.D.; investigation, G.A.D.; resources, G.A.D.; data curation, G.A.D.; writing—original draft preparation, G.A.D.; writing—review and editing, N.S.B. and M.A.S.; visualization, G.A.D.; supervision, N.S.B. and M.A.S.; project administration, N.S.B.; funding acquisition, G.D, N.S.B. and M.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the research plan proposal was approved by the Departmental Council of the Department of Business Administration at the Faculty of Economics and Administration (FEA), King Abdulaziz University. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants, who were assured that their participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time without consequences. No sensitive or personally identifiable information was collected, ensuring the protection of participants’ privacy.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ahmad, N., Nasurdin, A., & Zainal, S. (2012). Nurturing intrapreneurship to enhance job performance: The role of pro-intrapreneurship organizational architecture. Journal of Innovation Management in Small and Medium Enterprise, 2012, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, A. A., & Badawi, N. S. (2023). Intrapreneurship at the individual-level: Does psychological empowerment matter? International Journal of Professional Business Review, 8(5), 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atatsi, E. A., Azila-Gbettor, E. M., & Mensah, C. (2021). Predicting task performance from psychological ownership and innovative work behaviour: A cross sectional study. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1917483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer Antoncic, J., & Antoncic, B. (2011). Employee satisfaction, intrapreneurship and firm growth: A model. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 111(4), 589–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avey, J. B., Avolio, B. J., Crossley, C. D., & Luthans, F. (2009). Psychological ownership: Theoretical extensions, measurement and relation to work outcomes. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30(2), 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avey, J. B., Wernsing, T. S., & Palanski, M. E. (2012). Exploring the process of ethical leadership: The mediating role of employee voice and psychological ownership. Journal of Business Ethics, 107(1), 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, T. J., Qian, S., Miao, C., & Fiet, J. (2014). The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: A meta-analytic review. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38, 217–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, T., Jia, D., Liu, S., & Shahzad, F. (2024). Psychological ownership and ambidexterity influence the innovative work behavior and job performance of SME employees: A mediating role of job embeddedness. Current Psychology, 43(16), 14304–14323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, M. S., Mahmood, R., & Lucky, E. O.-I. (2015). The mediating role of intrapreneurial orientation between leadership style, knowledge sharing behaviour and performance of malaysian academic leaders: A conceptual framework. Sains Humanika, 4(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control (p. ix, 604). W H Freeman/Times Books/Henry Holt & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Batool, U., Raziq, M. M., Obaid, A., & Sumbal, M. S. U. K. (2023). Psychological ownership and knowledge behaviors during a pandemic: Role of approach motivation. Current Psychology, 42(29), 25089–25099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R. W. (1988). Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(2), 139–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berisha, B., Ramadani, V., Gërguri-Rashiti, S., & Palalić, R. (2020). The impact of innovative working behaviour on employees’ working performance. In J. Leitão, A. Nunes, D. Pereira, & V. Ramadani (Eds.), Intrapreneurship and sustainable human capital: Digital transformation through dynamic competences (pp. 37–49). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, J. (2012). Management of innovation: Role of psychological empowerment, work engagement and turnover intention in the Indian context. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(5), 928–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanka, C. (2019). An individual-level perspective on intrapreneurship: A review and ways forward. Review of Managerial Science, 13(5), 919–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, H. P., & Wiersema, M. F. (1999). Matching method to paradigm in strategy research: Limitations of cross-sectional analysis and some methodological alternatives. Strategic Management Journal, 20(7), 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G., Pierce, J. L., & Crossley, C. (2014). Toward an understanding of the development of ownership feelings. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(3), 318–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cable, D. M., & Kay, V. S. (2012). Striving for self-verification during organizational entry. Academy of Management Journal, 55(2), 360–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carberry, E. J., Kim, J. O., Han, J. H., Weltmann, D., Blasi, J., & Kruse, D. (2024). Feeling like owners: The impact of high-performance work practices and psychological ownership on employee outcomes in employee-owned companies. International Review of Applied Economics, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpini, J. A., Parker, S. K., & Griffin, M. A. (2017). A look back and a leap forward: A review and synthesis of the individual work performance literature. Academy of Management Annals, 11(2), 825–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, D.-S. (2019). A study on the psychological ownership and innovative behavior: Focus on job satisfaction and job engagement. The Institute of Management and Economy Research, 10(1), 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y. W., & Koo Moon, H. (2011). The moderating effects of collectivistic orientation on psychological ownership and constructive deviant behavior. International Journal of Business and Management, 6(12), 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, V. I., & Borman, W. C. (2000). Investigating the underlying structure of the citizenship performance domain. Human Resource Management Review, 10(1), 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulacoglou, C., & Saklofske, D. H. (2017). Advances in latent variable measurement modeling. In Psychometrics and psychological assessment (pp. 67–88). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J. G., Rigtering, J. P. C., Hughes, M., Kraus, S., Cheng, C.-F., & Bouncken, R. B. (2020). Individual and team entrepreneurial orientation: Scale development and configurations for success. Journal of Business Research, 112, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J. G., & Slevin, D. P. (1991). A conceptual model of entrepreneurship as firm behavior. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16(1), 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, S., Tian, A. W., Newman, A., & Martin, A. (2017). Psychological ownership: A review and research agenda. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(2), 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, J., & Wennekers, S. (2008). Intrapreneurship; Conceptualizing entrepreneurial employee behaviour. Scales Research Reports, 2008, H200802. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org//p/eim/papers/h200802.html (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- De Jong, J. P. J., Parker, S. K., Wennekers, S., & Wu, C.-H. (2015). Entrepreneurial behavior in organizations: Does job design matter? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(4), 981–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T. K., & Henseler, J. (2015). Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Quarterly, 39(2), 297–316. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, B. D., Ewell, P. J., & Brauer, M. (2023). Data quality in online human-subjects research: Comparisons between MTurk, prolific, CloudResearch, qualtrics, and SONA. PLoS ONE, 18(3), e0279720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldermann, S. K., & Hiebl, M. R. W. (2022). Psychological ownership and stewardship behavior: The moderating role of agency culture. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 38(2), 101209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellnhofer, K., Puumalainen, K., & Sjögrén, H. (2016). Entrepreneurial orientation and performance—Are sexes equal? International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 22(3), 346–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, C. M., Simmering, M. J., Atinc, G., Atinc, Y., & Babin, B. J. (2016). Common methods variance detection in business research. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3192–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galván-Vela, E., Arango Herrera, E., Sorzano Rodríguez, D. M., & Ravina-Ripoll, R. (2021). State-of-the-art analysis of intrapreneurship: A review of the theoretical construct and its bibliometrics. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(4), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawke, J. C., Gorgievski, M. J., & Bakker, A. B. (2018). Personal costs and benefits of employee intrapreneurship: Disentangling the employee intrapreneurship, well-being, and job performance relationship. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(4), 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisler, E. (1993). Middle managers as internal corporate entrepreneurs: An unfolding agenda. Interfaces, 23(6), 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giang, H. T. T., & Dung, L. T. (2021). Transformational leadership dimensions and job-based psychological ownership as facilitators in international intrapreneurship of family firms. The South East Asian Journal of Management, 15(2), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giang, H. T. T., & Dung, L. T. (2022). The effect of internal corporate social responsibility practices on firm performance: The mediating role of employee intrapreneurial behaviour. Review of Managerial Science, 16(4), 1035–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielnik, M. M., Uy, M. A., Funken, R., & Bischoff, K. M. (2017). Boosting and sustaining passion: A long-term perspective on the effects of entrepreneurship training. Journal of Business Venturing, 32(3), 334–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M. A., Neal, A., & Parker, S. K. (2007). A new model of work role performance: Positive behavior in uncertain and interdependent contexts. Academy of Management Journal, 50(2), 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Mena, J. A. (2012). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., Jr., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrick, A. B., Burrows, S., Waddingham, J. A., & Crossley, C. D. (2024). It’s my business! The influence of psychological ownership on entrepreneurial intentions and work performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 45(8), 1208–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.-S., Chiang, H. H., & Chang, A. (2010). Employee participation in decision making, psychological ownership and knowledge sharing: Mediating role of organizational commitment in Taiwanese high-tech organizations. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(12), 2218–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.-S., Chiang, H.-H., McConville, D., & Chiang, C.-L. (2015). A longitudinal investigation of person–organization fit, person–job fit, and contextual performance: The mediating role of psychological ownership. Human Performance, 28(5), 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.-X., Chen, Z., Mahsud, M., & Yu, Y. (2024). Organizational psychological ownership and innovative work behavior: The roles of coexisting knowledge sharing and hiding across organizational contexts. Journal of Knowledge Management, 28(8), 2197–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayati, K., & Caniago, I. (2012). Islamic work ethic: The role of intrinsic motivation, job satisfaction, organizational commitment and job performance. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 65, 1102–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinonen, J., & Toivonen, J. (2008). Corporate entrepreneurs or silent followers? Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 29, 583–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Perlines, F., Ariza-Montes, A., & Blanco-González-Tejero, C. (2022). Intrapreneurship research: A comprehensive literature review. Journal of Business Research, 153, 428–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E. T. (1997). Beyond pleasure and pain. American Psychologist, 52(12), 1280–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E. T. (1998). Promotion and prevention: Regulatory focus as a motivational principle. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 30, pp. 1–46). Academic Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hom, P. W., Mitchell, T. R., Lee, T. W., & Griffeth, R. W. (2012). Reviewing employee turnover: Focusing on proximal withdrawal states and an expanded criterion. Psychological Bulletin, 138(5), 831–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsby, J. S., Kuratko, D. F., & Zahra, S. A. (2002). Middle managers’ perception of the internal environment for corporate entrepreneurship: Assessing a measurement scale. Journal of Business Venturing, 17(3), 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.-Y., Yang Lin, S.-M., & Hsieh, Y.-J. (2021). Cultivation of intrapreneurship: A framework and challenges. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 731990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jussila, I., Tarkiainen, A., Sarstedt, M., & Hair, J. (2015). Individual psychological ownership: Concepts, evidence, and implications for research in marketing. The Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 23, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Koopmans, L., Bernaards, C. M., Hildebrandt, V. H., De Vet, H. C. W., & Van Der Beek, A. J. (2014). Construct validity of the individual work performance questionnaire. Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine, 56(3), 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmans, L., Bernaards, C. M., Hildebrandt, V. H., Schaufeli, W. B., De Vet Henrica, C. W., & Van Der Beek, A. J. (2011). Conceptual frameworks of individual work performance: A systematic review. Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine, 53(8), 856–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuratko, D. F., Hornsby, J. S., & Bishop, J. W. (2005). Managers’ corporate entrepreneurial actions and job satisfaction. The International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 1(3), 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latan, H., Hair, J. F., & Noonan, R. (Eds.). (2023). Partial least squares path modeling: Basic concepts, methodological issues and applications. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K., & Kim, Y. (2021). Ambidexterity for my job or firm? Investigation of the impacts of psychological ownership on exploitation, exploration, and ambidexterity. European Management Review, 18(2), 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, C. T., & Rasli, A. (2014). The relationship between innovative work behavior on work role performance: An empirical study. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 129, 592–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LePine, J., & Van Dyne, L. (1998). Predicting voice behavior in work groups. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 853–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F., Chow, I. H.-S., Zhang, J.-C., & Huang, M. (2019). Organizational innovation climate and individual innovative behavior: Exploring the moderating effects of psychological ownership and psychological empowerment. Review of Managerial Science, 13(4), 771–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M. A., Ahmad, S., & Poespowidjojo, D. A. L. (2018). The role of psychological safety and psychological empowerment on intrapreneurial behavior towards successful individual performance: A conceptual framework. Sains Humanika, 10(3), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M. A., Ahmad, S., & Poespowidjojo, D. A. L. (2020). Intrapreneurial behavior, big five personality and individual performance. Management Research Review, 43(12). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M. A., Ahmad, S., & Poespowidjojo, D. A. L. (2022). Psychological empowerment and individual performance: The mediating effect of intrapreneurial behaviour. European Journal of Innovation Management, 25(5), 1388–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]