Abstract

This study investigates how strategic innovation influences operational quality, focusing on the mediating effects of transformational and transactional leadership, as well as process innovation, within manufacturing organizations in Colombia. It employs structural equation modeling to analyze data from 180 valid questionnaires. The method allows for an intricate examination of the relationships between strategic innovation and the key organizational variables. The findings reveal that while strategic innovation significantly enhances transactional leadership and process innovation, it does not affect transformational leadership or improve operational quality. This discrepancy with existing literature highlights an urgent need for enhanced leadership development programs that can effectively integrate innovation strategies. This study contributes to the field by delineating specific organizational capabilities and strategies to enhance leadership effectiveness in managing innovation. It underscores the necessity of refining leadership approaches to achieve operational excellence and sustain a competitive edge. The study calls for a more nuanced understanding of how leadership styles can better align with strategic innovation initiatives to improve organizational performance.

1. Introduction

In today’s rapidly evolving market environment, strategic innovation has emerged as a key driver of operational quality and sustained competitive advantage (Lei & Slocum, 2005). However, the conventional wisdom that leadership is merely a facilitator of innovation overlooks the complexities involved in the ways leadership styles shape the outcomes of innovation efforts. While many studies assume that transformational leadership is the primary enabler of innovation, others contend that transactional leadership can also contribute to innovation outcomes by ensuring efficiency and control (Alrowwad et al., 2020). These assumptions, although widely accepted, have rarely been critically examined or problematized, especially in the context of manufacturing organizations in developing economies (Luoto et al., 2017). This study seeks to challenge these assumptions by investigating how different leadership styles interact with strategic innovation to influence operational quality, with a specific focus on the Colombian manufacturing sector. The underlying assumption that strategic innovation is inherently aligned with positive operational outcomes is questioned here, as previous research has yielded contradictory results—particularly regarding the role of leadership in the driving process of innovation and quality improvements. By focusing on the complex and potentially contradictory relationship between leadership styles, strategic innovation, and operational quality, this research aims to offer a more nuanced understanding of how innovation strategies influence organizational performance (Cortes & Herrmann, 2021). The research question driving this study is as follows: What role do innovation strategies, leadership styles, and process innovation play in enhancing operational quality, and how do they challenge existing assumptions about their direct relationship? The article proceeds as follows. Section 2 reviews the relevant literature and identifies the underlying assumptions that guide the theoretical model. Section 3 details the methodology and empirical analysis techniques used to test the hypotheses. Section 4 presents the data analysis results, followed by a discussion of the findings in Section 5, which explores the implications of the study’s challenge to conventional wisdom.

Along with the entrepreneurial spirit itself, innovation is one of the elements that scholars, practitioners, and business owners pay particular attention to. According to several authors (Benamati et al., 2010; Dvouletý, 2018; Evangelista & Vezzani, 2010), innovation is any response from the organization to create new knowledge or any activity in strategy or process change, product or service creation, organizational innovation, or gaining a sustainable competitive advantage. As a result, innovation is intimately related to an organization’s strategic adaptability (Hughes et al., 2018). If innovative techniques are correctly implemented, they may create new goods, access new markets, increase organizational efficiency, and improve commercial and economic growth (Sarkar, 2013).

Kahn (2018) defines innovation in terms of three different aspects: the outcome, the process, and the attitude. The outcomes are what innovation offers. Innovation as a process establishes the goals to be met and the structure of innovation (Lappalainen et al., 2023). The internalization of innovation by every employee within an environment and organizational culture that supports it is considered when discussing innovation as a mindset (Barrera & Shah, 2023).

In a previous viewpoint, Tidd and Bessant (2014) hypothesized that process innovation plays a strategic function that is at least as significant as—if not more so—the creation of new products, which the market considers the pinnacle of innovation. The process’s uniqueness may offer advantages that the competition has not yet realized. A definite competitive advantage can achieve something no one else has done or do something better than others.

According to (Utterback & Abernathy, 1975), the temporal dynamics of innovations in products, services, and processes are distinct because the process will be perfected by applying new technologies, allowing companies to concentrate on cost-cutting measures and gain a larger market share or a more decisive competitive edge. Today, innovation is viewed as a series of actions to create an innovation environment or innovation group, including problem-solving processes (Dosi, 1988), interactive processes involving relationships between various organizations and actors, diversified learning processes, and knowledge exchange (Edquist, 2001; Patel & Pavitt, 1994). Today, innovation is viewed as a series of actions to create an innovation environment or innovation group, including problem-solving processes (Dosi, 1988), interactive processes involving relationships between various organizations and actors, diversified learning processes, and knowledge exchange (Edquist, 2001; Patel & Pavitt, 1994).

Although brand-new goods are considered at the forefront of innovation, process evolution also serves a crucial strategic purpose. A significant source of advantage is doing something that no other organization can do or performing better than any other organization. Competitors may create and launch new products that threaten the company’s current market leadership; as a result, the company needs to be able to counteract such danger with its product innovation. The intricacy of their operations and the ensuing high entry barriers for other rivals trying to imitate them are two of the primary factors contributing to the survival of small businesses in fiercely competitive marketplaces (Porter, 1985). It is crucial to note that if a company cannot produce innovation, its competitive edge will eventually erode. Other businesses will take the initiative by improving their value offering, business strategy, or internal efficiency.

Operational innovation, which combines invention and modifications to operational procedures, must be one of the primary objectives of any strategic approach (Bordella et al., 2011). Operational innovation, as defined by (Hammer, 2004), is the creation and use of new methods of performing tasks; as such, it is disruptive innovation. Operational innovation is closely related to paradigmatic innovation since it necessitates the elimination of long-standing routines and processes, adjusting how an organization carries out its work, and even changing one’s way of thinking. Note that operational innovation is distinct from operational excellence. Compared to other strategies for boosting growth, operational innovation has the benefit of requiring fewer resources for execution (Hammer, 2004). Four aspects of innovation are identified by (Tidd et al., 2005) for every organization: - Product innovation: modifications to the organization’s goods or services. - Process innovation: modifications to an organization’s internal procedures. - Position innovation: modifications to how goods or services are introduced. - Paradigm innovation: modifications to the organization’s mental models.

Additionally, according to (Lundvall, 1992), practically all inventions reflect prior knowledge (learning) combined with new applications, supporting the idea of evolution. This affirmation focuses on the importance of links as crucial participants in a creative environment, the necessity of contact between institutions, and the ability to concentrate on information generation, dissemination, and sharing (Wakabayashi et al., 2024).

1.1. Strategy

Innovation is a critical component that enables a business to establish a dominant market position and boost profitability in an environment where competition is rising (Ratten & Ferreira, 2017). The results may be comparable but still distinct because each organization’s application of each of the drivers considered in the self-assessment tool is different. Formal strategies must be viewed as part of a more extensive process of continuous learning from experience and from others to cope with complexity and change since businesses make decisions in fast-growing and changing competitive contexts (Tidd, 2013).

Naming the elements of innovation that affect the strategy is fundamental since, in the last fifteen years, many tools have been developed that seek to improve innovation management, propose models of innovation management systems, and expand the proposal of innovation management standards. However, studies show limited knowledge about innovation management, using a system and routines for this purpose, the best practices, and the relevant conditions that modify their actions (Quinhões & Lapão, 2023). Long-term goals, strategies for achieving them, and securing the required resources are all part of the strategy (Carvalho & Madeira, 2021).

Furthermore, a strategy is suggested to specify how the goals will be achieved. Planning and strategy are distinct ideas in this sense. Successful firms’ extensive market ability—regrettably, no longer accurate information—is one of the most significant barriers to strategic transformation. The industry needs innovation because of this. According to (Hendel, 2017), innovation generates unique strategies that stand out in each market. To achieve these innovative talents, operational effectiveness and strategic flexibility are essential (Boer et al., 2006; Santa et al., 2019). Innovative tactics thus produce long-lasting competitive advantages.

Strategic innovation, according to studies by Cefis and Marsili (2006), Audretsch (1995), and Dervitsiotis (2010), is essential for an organization’s ability to survive and establish a lasting competitive edge. Innovative value chain strategies founded on an organization’s core competencies produce sustainable competitive advantages; the innovation encourages companies to develop their services, creating and maintaining value for stakeholders (Indah et al., 2021). Strategies help turn technology advancements and put production know-how to use to boost corporate growth and enable enterprises to adapt to the competitive environment, which is constantly changing.

This is evidenced in studies such as (Cefis et al., 2023), which show that different types of innovation affect the probability of exiting the market in substantially different ways, with no clear relationship between the kind of innovation and the type of business exit (Cefis et al., 2023).

1.2. Processes Innovation

Innovation is a method that aligns with an organization’s desired outcomes (Kahn, 2018). Tidd (Tidd, 2013) elaborates on process innovation by developing a model that outlines key questions organizations must address to effectively search for opportunities, manage the selection process, oversee the implementation of innovation projects from inception to completion, and understand how employees perceive the organization’s support for innovation through ideas and models. Process innovation, in particular, is a powerful tool and a source of competitive advantage. It involves creating products or services in a novel or distinctive way, improving how they are manufactured, distributed to customers, or how the supply chain operates (Tidd, 2013). Different organizational variables’ internal and external integration and their combination to grow profit are requirements when an organization tries to create new competitive advantages (Ettlie & Reza, 1992; Lambardí & Mora, 2014). Information technology is crucial in the conversion of data into corporate knowledge. Supporting new information pertinent to the company fosters an environment where new knowledge is produced. Such fresh details are essential for the success of strategic process innovation, aid organizational efficiency, and ultimately aid in the most efficient development of new goods (Brown & Eisenhardt, 1995). Additionally, knowledge improves organizational procedures and the latest technology management, which increases effectiveness and efficiency (Zhang & Lado, 2001).

Moreover, research indicates that successful process innovation is often driven by a collaborative culture within the organization. When employees at all levels are encouraged to contribute ideas and solutions, the likelihood of innovative breakthroughs increases significantly (Hoe, 2006; Nonaka et al., 1996). This inclusive approach not only fosters a sense of ownership among employees but also enhances the overall adaptability of the organization to changing market conditions (Drucker, 1985; Shane, 2002). As organizations embrace process innovation, they must also invest in continuous learning and development to keep pace with technological advancements and maintain their competitive edge (Teece et al., 1997).

1.3. Operational Quality (OQ)

Porter (1996) states that operational effectiveness is the capacity to use procedures built around an organization’s core competencies to outperform competitors in the same activities. As a result, companies need help to provide exceptional performance in a globalized market characterized by fierce rivalry and quick change. Consequently, businesses search for methods to raise the profitability and effectiveness of their services and operations (Grundy, 2006).

One of the most critical aspects of business success is operational effectiveness, which is related to quality and cost leadership. To achieve this goal, organizations focus on attaining high levels of operational effectiveness; the following dimensions must be examined (Rejeb et al., 2008; Santa et al., 2009; Tegethoff et al., 2021).

Providing clients with what they want, when they want it, is what quality is all about. Customers have distinct needs when it comes to products and services. That means meeting their needs and offering top-notch products or services. However, whether the business sells goods or services is irrelevant because quality demands various working methods. Production timelines, response times, wait times, delivery times, delays, warranty periods, service personnel, service protocols, after-sales services, repair quality, locations, and accountability attitudes are just a few factors that might impact quality (Oliveira-Dias et al., 2022).

The time required to create new goods or services and address client needs can be considered speed. Speed is linked to important traits, including quick adaptation, swift movements, and intimate relationships among all organizational constituents. Due to the constant changes in the organizational environment, speed can be seen as a critical talent that any organization needs (Tidd & Bessant, 2020).

Accordingly, operational effectiveness requires controlling and regulating an organization’s operations and overseeing and assessing its procedures’ performance (Santa et al., 2014). If a business performs better, faster, and more smoothly than its rivals, operational effectiveness might also be the secret to outperforming them in outcomes (Namnai et al., 2015). Measurement concerns can be used to classify the underlying challenges. Quantitative and qualitative gains are commonly noted in service operation situations but are challenging to measure (Brigham & Ehrhardt, 2016).

1.4. Leadership

Academics have traditionally studied leadership from two perspectives, one focusing on positional leadership within an organization’s hierarchy and one that views leadership as a process of social influence occurring naturally in a social system (Yetton & Crouch, 1983). These perspectives have determined four approaches to leadership theories: traits, behaviorist, contingency, and transformational (Bruch & Walter, 2007). These approaches have examined the qualities and behaviors of leaders, how they employ power and influence, adapt their behavior to situations, and manage operations in dynamic business environments (Prabhu & Srivastava, 2023). According to (Al-Taneiji, 2006), none of these four approaches is mutually exclusive or determined for a certain period.

The main goal of human resources at a company is to effectively manage its workforce by encouraging positive employee attitudes, such as increased excitement, productivity, and job satisfaction, and decreasing negative attitudes, such as higher turnover, tardiness, and disruptive behavior at work. Because they can either encourage or impede creativity and innovation within the company, employee opinions about the organization’s leadership, practices, and policies must be prioritized as enablers of innovative outputs (Nasir et al., 2022).

Kotter (2008) states leadership involves persuading people to voluntarily dedicate themselves to achieving the group’s goals. To do so, the group must have a shared understanding of a specific organizational function and possess the knowledge, skills, experience, and abilities necessary to maintain momentum and urgency (Mouazen et al., 2023). The leadership among the group members will always determine how successfully an organization implements change (Jaramillo et al., 2009).

The literature distinguishes between two types of leadership—transactional and transformational—and highlights an inherent dissonance between them. Despite their distinctive differences, these leadership styles can coexist within the same leader and be complementary (Mouazen et al., 2023). Mackenzie et al. (2001) found that transformational leadership behaviors have stronger direct and indirect relationships with performance than transactional behaviors. Conversely, Howell and Avolio (1993) discovered that transactional leadership negatively impacted performance. However, the latest studies that specifically consider the impact of transformational and transactional leadership styles on job satisfaction are significantly related to job success and career satisfaction. These contrasting viewpoints underscore the complexity of leadership dynamics. Below is a summary of each category of leadership traits (Cinnioğlu et al., 2020; Riaz & Hussain Haider, 2010; Skopak & Hadzaihmetovic, 2022).

1.4.1. Transactional Leadership

With transactional leadership, the team’s leader takes on the role of a change agent, enacting major adjustments to boost output. The mainstay of this leadership approach is an incentive structure that has a favorable correlation with employees’ output. This leadership style comprises a reward system that positively correlates with the subordinate’s performance behavior (Bennett, 2009). According to N. P. Podsakoff et al. (2010), contingent rewards and punishments are examples of transactional leadership practices that significantly impact workers’ attitudes and productivity. The relationship between transactional leaders and their subordinates can be examined using three criteria. The leader will first outline the benefits that employees will obtain if their performance meets expectations, as they know their needs. Secondly, the manager gives credit to employees for their work. Third, leaders are open to hearing what they say when followers’ interests align with the significance of the tasks that they are accountable for completing (Bass, 1997).

The relationship between transactional leaders and their subordinates can be examined using three criteria. The leader will initially outline the advantages employees can expect if their performance meets established standards, demonstrating awareness of their needs. Next, the manager acknowledges the efforts of employees. Additionally, leaders should be receptive to feedback when followers’ interests align with the critical tasks. Furthermore, they need to adapt their transactional leadership methods by ensuring the promised rewards are granted in return for the team’s contributions during the final three phases of the change model. They should also engage in proactive management by monitoring expected behaviors and promptly reporting performance discrepancies to higher management and change strategists, intervening as necessary to implement corrective measures efficiently. Leaders must delegate authority to lower levels to resolve minor issues while centralizing strategy formulation and significant decision-making processes (Bass, 1997; Mouazen et al., 2023).

1.4.2. Transformational Leadership

This leadership style aims to accomplish the goals of the organization’s chief executive without compromising the team’s goals. Transformational leaders can motivate their followers to go above and beyond expectations by setting goals and aspirations, communicating these in a vision, and serving as appropriate role models whose behavior is based on contingent reward and punishment behavior (P. M. Podsakoff et al., 1990). Similarly, knowledge management and transformational leadership both strongly depend on trust and help explain differences in the inventiveness and competitiveness of organizational employees.

Transformational leaders are perceived as enthralling people who stimulate their team members’ minds and feelings, motivate and uplift them instead of controlling them, and kindle commitment to the company’s mission and goals. They also have experience, knowledge, and competence in the activity they oversee, are eager to take chances, challenge others to think independently and uplift the spirits and enthusiasm of the team. One characteristic of transformational leaders is the ability to foster an environment where followers go above and beyond expectations (Bar-On, 2006). Although this is a very effective leadership style, research has shown that, on occasion, it must be combined with other styles to ensure that the organization’s procedures are as effective as possible (Leban & Zulauf, 2004).

Implementing transformational leadership within an organization can significantly enhance its overall performance. Transformational leaders who value individual initiatives that can benefit the organization and encourage advances brought about by team members’ creative practices are crucial in meeting the needs of both internal and external stakeholders for innovation and change. Their leadership is essential for emerging innovative practices (Tegethoff et al., 2021).

Asbari et al. (2020) show that, despite the criticism that transformational leadership has received as elitist in a complex organizational environment, there is still a strong relevance between transformational leadership patterns and the firm’s desire to innovate. Their studies show that transformational leadership can maintain continuous and sustainable organizational innovation. Thus, this research suggests:

Hypothesis 1 (H1):

Strategic innovation positively impacts transactional leadership.

Hypothesis 2 (H2):

Strategic innovation positively impacts transformational leadership.

1.5. Relationship Between Strategic Innovation and Process Innovation

Hypothesis 3 (H3) posits that strategic innovation positively impacts process innovation and is crucial because it highlights the interdependence between innovative strategies and the enhancement of organizational processes. This paper suggests that strategic innovation catalyzes process innovation, enabling organizations to streamline operations and improve efficiency. By integrating strategic innovation, firms can better align their processes with their overall strategic goals, enhancing operational effectiveness and competitiveness. This relationship is supported by the notion that strategic innovation fosters an environment where continuous improvement and adaptation are encouraged, ultimately driving process innovation. Moreover, empirical evidence from various studies underscores the significance of this hypothesis. For instance, Tidd and Bessant (2020) emphasize that process innovation plays a critical strategic role, often surpassing product innovation in importance. Similarly, Kafetzopoulos and Skalkos (2019) found that effective process innovation significantly enhances organizational efficiency and performance. This alignment of strategic and process innovations ensures the smooth implementation of new ideas and facilitates adaptation to market changes and technological advancements, thereby securing a sustainable competitive advantage. The interplay between strategic and process innovations underscores organizations’ need to invest in strategic initiatives that foster an innovative culture and drive continuous process improvements.

Hypothesis 3 (H3):

Strategic innovation positively impacts process innovation.

1.6. Relationship Between Strategic Innovation and Operational Quality

Hypothesis 4 (H4) states that strategic innovation positively impacts operations quality and emphasizes the link between strategic innovation initiatives and enhancing quality in organizational operations. Organizations can streamline processes, enhance service delivery, and meet higher quality standards by implementing innovative strategies. This relationship is corroborated by research suggesting that strategic innovation fosters an environment conducive to continuous improvement, leading to better quality outcomes in operations (Santa et al., 2019). Furthermore, empirical studies support the significance of this hypothesis. For instance, Molina-Azorín et al. (2015) found that integrating quality and strategies significantly boosts competitive advantage. Innovation in processes and services directly enhances operational quality, increasing customer satisfaction and performance. Organizations can better address customer needs and preferences by aligning strategic innovation with quality management practices, ultimately leading to higher operational efficiency and service quality. This alignment is crucial for competitive markets, where maintaining high operational standards is necessary for retaining customer loyalty and achieving long-term success.

Hypothesis 4 (H4):

Strategic innovation positively impacts operations quality.

1.7. Relationship Between Transformational Leadership and Process Innovation

To explain hypothesis 5, the text shows that the literature suggests that Transformational leadership is widely recognized for its potential to drive innovation within organizations. This leadership style, characterized by inspiring and motivating employees, fosters an environment conducive to creativity and change. Understanding the relationship between transformational leadership and process innovation is pivotal for understanding how leadership can influence organizational outcomes. Transformational leaders exhibit behaviors that encourage followers to transcend their self-interests for the sake of the organization. They provide a clear vision, foster an innovative culture, and promote an environment where employees feel empowered to take risks and think creatively (Bycio et al., 1995). This empowerment is crucial for process innovation, which involves implementing new or significantly improved production or delivery methods. Research has shown that transformational leadership positively impacts process innovation by enhancing employees’ intrinsic motivation and organizational commitment. When leaders articulate a compelling vision and demonstrate a commitment to innovation, they can inspire employees to engage in innovative behaviors, facilitating process innovation. Moreover, transformational leaders can build trust and foster a supportive climate, which is essential for experimentation and the development of new processes (Gumusluoglu & Ilsev, 2009).

Hypothesis 5 (H5):

Transformational leadership positively impacts process innovation.

1.8. Relationship Between Transactional Leadership and Process Innovation

Hypothesis 6 postulates that transactional leadership significantly impacts process innovation within organizations. This hypothesis is grounded in the understanding that through their structured and performance-oriented approach, transactional leaders can foster an environment conducive to incremental and process-oriented innovations. Research indicates that transactional leadership is crucial in establishing clear goals and performance expectations for successful process innovation. By setting explicit objectives and monitoring progress, transactional leaders ensure that employees adhere to established protocols while seeking incremental improvements. This approach aligns with the findings of (Jansen et al., 2009), who assert that transactional leadership facilitates a disciplined work environment where process efficiencies can be identified and enhanced systematically. Moreover, transactional leadership’s reliance on reward and punishment mechanisms can stimulate innovation by incentivizing employees to find more efficient ways to perform tasks. Bass and Avolio (1993) support this, highlighting that transactional leaders effectively utilize contingent rewards to motivate employees towards achieving specific goals, fostering a culture of continuous improvement and process innovation. These incentives encourage employees to innovate within the bounds of existing processes, leading to incremental advancements that enhance overall organizational efficiency.

Hypothesis 6 (H6):

Transactional leadership positively impacts process innovation.

1.9. Relationship Between Transactional Leadership and Operational Quality

As hypothesis 7 suggests, several empirical studies have supported the positive impact of transactional leadership on operational quality. For instance, Wang et al. (2011) conducted a meta-analysis of leadership styles and found that transactional leadership significantly enhances operational outcomes by ensuring adherence to standards and minimizing errors. Their findings indicate that transactional leaders’ focus on performance and accountability leads to higher operational quality, as employees are consistently guided and monitored toward achieving specific objectives. Additionally, a study by (Den Hartog et al., 1997) highlighted that transactional leadership positively correlates with organizational performance metrics, including operational quality. The researchers observed that the transactional leader’s emphasis on clear directives and performance-based rewards fosters an environment where employees are more likely to meet or exceed operational standards.

Hypothesis 7 (H7):

Transactional leadership positively impacts operational quality.

1.10. Relationship Between Transformational Leadership and Operational Quality

Empirical evidence suggests a strong link between transformational leadership and improved operational quality, as hypothesis 8 shows. For instance, a study by (Jha, 2014) found that transformational leadership positively influences quality performance in the manufacturing sector. The study revealed that leaders who exhibit transformational behaviors such as idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration are likelier to foster an environment where employees are committed to quality improvements. Moreover, the relationship between transformational leadership and operational quality can be explained through the firm’s resource-based view (RBV) lens. This theoretical perspective posits that leaders who can effectively mobilize and utilize organizational resources, including human capital, are better positioned to achieve superior operational outcomes (Ferreira et al., 2016). By their ability to inspire and motivate employees, transformational leaders enhance the organization’s human capital, leading to improved operational quality. Further supporting this hypothesis, a meta-analysis by (Wang et al., 2011) indicated that transformational leadership is positively correlated with organizational performance outcomes, including quality metrics. The analysis encompassed various industries and highlighted that transformational leadership consistently leads to better quality performance, underscoring the universality of this relationship.

Hypothesis 8 (H8):

Transformational leadership positively impacts operational quality.

1.11. Relationship Between Process Innovation and Operational Quality

The relationship between process innovation and operational quality has garnered significant attention in recent years, highlighting the critical role of innovative practices in enhancing organizational performance. Process innovation, defined as implementing new or significantly improved production processes, techniques, or methods, is instrumental in achieving operational excellence (Davenport, 1993). The hypothesis that process innovation significantly impacts operational quality can be substantiated through various empirical and theoretical perspectives. Firstly, process innovation leads to the enhancement of operational quality by optimizing efficiency and reducing errors. According to (Hammer & Champy, 1993), re-engineering processes often results in streamlined operations that minimize redundancy and waste, thereby improving the overall quality of output. This is supported by empirical studies that demonstrate a positive correlation between the adoption of innovative processes and improvements in product quality (Koc & Ceylan, 2007). Furthermore, integrating advanced technologies and methodologies through process innovation fosters a culture of continuous improvement, which is crucial for maintaining high operational standards. For instance, implementing Total Quality Management (TQM) practices is often accompanied by innovative process changes that enhance quality control mechanisms (Prajogo & Sohal, 2003). This continuous improvement cycle ensures that operational processes are constantly evaluated and refined, leading to sustained quality improvements.

Hypothesis 9 (H9):

Process innovation positively impacts operational quality.

In addition to exploring the complex interplay between strategic innovation, leadership styles, and operational quality, this study also addresses the limited understanding of how contextual factors shape leadership behaviors and their outcomes. While much of the existing research focuses on leadership traits and styles, less attention has been paid to the role of the organizational context in influencing how leaders behave and make decisions. According to (Oc, 2018)’s integrative framework, context plays a pivotal role in shaping leadership by influencing both the leaders’ behaviors and the outcomes of those behaviors. Oc (2018) emphasizes that leadership is not only a product of individual characteristics or styles but is also deeply embedded within the broader organizational and environmental context. This framework links contextual factors—such as organizational culture, industry dynamics, and the external business environment—to leadership outcomes, suggesting that the effectiveness of leadership strategies may vary depending on the specific context in which they are applied. By integrating this framework, the current study offers a deeper exploration of how the manufacturing context in Colombia influences leadership behaviors and the impact those behaviors have on the success of strategic innovation and operational quality initiatives. In doing so, this study seeks to expand our understanding of how contextual nuances affect leadership effectiveness, challenging the one-size-fits-all approaches that often dominate the literature on leadership and innovation.

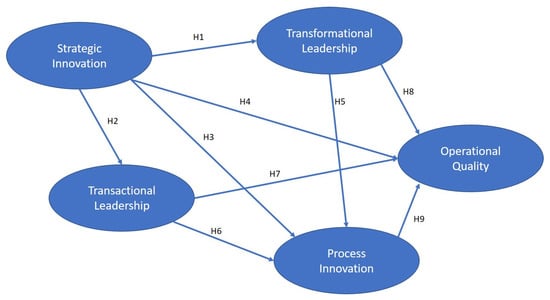

As a result, following the literature study, we suggest the hypothetical model shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The hypothetical model developed for this study.

2. Materials and Methods

In this investigation, a survey instrument was developed based on the guidelines provided by (Hair et al., 2010) and their best-fit model to test the hypotheses depicted in Figure 1. Invitations holding a link to the survey hosted on Microsoft Forms were sent to potential participants. The data collected through the online survey can be easily transferred to SPSS, using the advantages of digital data collection.

The variables in this study are measured at the individual level. This approach ensures that the study captures the perceptions and experiences of individual respondents, which is critical for understanding the nuanced effects of leadership styles and innovation strategies within specific organizational contexts (Jong, 2007). By focusing on individual-level data, we can assess how leadership behaviors, influenced by personal experiences and perceptions, shape innovation outcomes and operational quality (Černe et al., 2013). This approach aligns with previous research that suggests individual perceptions play a significant role in how organizational strategies are implemented and how their success is perceived. The data, collected from 180 respondents, all holding various managerial and supervisory roles within manufacturing organizations, provide a comprehensive view of these dynamics from the perspective of those directly involved in the leadership and innovation processes (Baltaci & Balcı, 2017; Cortes & Herrmann, 2021).

We carefully chose responses from a convenience sample, taking into account each person’s tenure, position, experience, and knowledge. The study’s sample comprised 180 respondents employed by manufacturing enterprises in Colombia’s Valle del Cauca industrial zone. We selected managers, engineers, and employees with supervisory responsibilities. After each questionnaire was reviewed for completeness, it was determined that several needed to be more valuable due to inconsistencies, significant gaps in the data, or respondents’ lack of interest in taking on leadership roles. In the end, seventy-six surveys were dropped. A total of 59.30% of those surveyed gave a response.

Adhering to (Hair et al., 2010)’s recommendations justified the study’s sample size. For an SEM model, more covariances must be in the input data matrix than the required minimum sample size. Additionally, the minimum appropriate sample consists of ten respondents for each attribute. Given this, a five-construct SEM model has more than 180 valid replies.

The questionnaire was divided into four components after carefully reviewing the literature. A Likert-type scale with five points (strongly disagree–strongly agree) was employed to assess claims regarding operationalizing the different notions. The respondents’ opinions on the various questions were reflected in this scale. The purpose of the first component of the questionnaire was to profile the individuals. This investigation did not employ the (Wong & Law, 2002) emotional intelligence scale, which provided the basis for 16 of the second section’s emotional intelligence statements.

The transformational and transactional leadership factors were measured using the Leadership Style Questionnaire [CELID] (Solano et al., 2004). Based on Bass’s leadership theory, this questionnaire explicitly identifies these criteria in quantifiable terms (Bass & Avolio, 1990). The Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire, or MLQ for short, is where the CELID instrument started. It offers an understanding of the transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire (lack of leadership) leadership ideologies that are most frequently used (Bass & Avolio, 1990). It also has two surveys for leaders (CELID-A) and subordinates (CELID-S), each with 34 self-administered response options.

The questions about strategic innovation were adopted from the self-assessment tool developed by Tidd, Bessant, and Pavitt (Tidd, 2013). The questions about operational quality were taken from Operational Effectiveness by (Santa et al., 2014).

The third section, which measures the behavioral aspects of organizational citizenship, was developed following the research of (Asbari et al., 2020). Last, a modified version of the questionnaire created by (Santa et al., 2014) and (Santa et al., 2019) was utilized to examine the operational effectiveness construct.

The Colombian ethics committee at Colegio de Estudios Superiores de Administración (CESA) reviewed the questionnaire to ensure the questions were objective, non-threatening, and devoid of social desirability bias. Before answering the questionnaire, the respondents were also advised that all information would be kept entirely confidential, that the responses would be compiled and used for research, that they would be granting permission for this use by completing the survey, and that they could withdraw at any time. By respecting ethical principles, the researchers conducted this study using ethical protocols.

Data Analysis

The average mean evaluations of the statements were used to construct the variables of the structural equation model. This methodology is suitable for our study, and the examination of latent variables and their interrelationships and the compatibility between the necessary sample and the gathered data are all met (Nachtigall et al., 2003). To examine the data, we used AMOS software version 28 and SPSS (https://www.ibm.com/spss). One of the analyses confirmed the hypothesized model depicted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Area of Responsibility.

Table 1 shows the demographics for this study broken down by the respondents’ areas of responsibility. According to the data gathered, 27% of the respondents had administrative duties, 20% worked in logistics, and 10% worked in engineering and operations. Another noteworthy aspect of the sample is the large number of respondents who work in operational roles.

To assess how well the model fits the data overall and examine the relationships between continuous latent and observable variables, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was employed (Cooksey, 2007; Hair et al., 2010). The elements were initially loaded on a single construct, and factor loadings were computed. The items-to-total correlation and Cronbach’s alpha coefficient were used to correlate the latent components to assess internal consistency. Table 2 contains a list of the constructs’ coefficient values. The following stages outline the statistical study that was performed to determine the predictiveness and indices of the model.

Table 2.

Reliability measures.

- Applying confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with the following configurations:Difference: asymptotically free of distribution;Covariances provided as input: impartial;Analysis of covariances must be performed: maximum likelihood.

- Estimating factor loading (evaluation of the connection between continuous latent variables and observable variables).

- Coherence inside. Everything over 0.70 (Hair et al., 2010). Table 2 displays Cronbach’s alpha coefficient.

- Construct validity testing (CFA).

AMOS was used to analyze the multicollinearity between dimensions. The data showed no signs of multicollinearity. The regression analysis yielded the variance inflation factor (VIF), used to calculate the degree of interaction between two independent variables. The VIF value is a commonly used metric to evaluate multicollinearity.

To prevent overfitting, we evaluated the model’s fitting propensity using the parsimony indices PNFI = 0.755, PCFI = 0.832, and PGFI = 0.695 (Byrne, 2016).

To assess the dependability of the model, we contrasted the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE). AVE calculates the percentage of indicator variance that may be attributed to the latent variable instead of measurement error (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The AVE ought to be more than 0.50. According to (Chin, 2010), the latent construct explains more than half of the indicator variance. Using the composite reliability measure developed by (Werts et al., 1974), we evaluated internal consistency (reliability). Cronbach’s alpha, a lower-bound reliability measure, is considered less accurate than composite reliability. Construct loading factors, Cronbach’s alphas, squared AVE statistics, and composite reliabilities are all compiled in Table 2. According to the composite reliability score, the data show that the measures have internal solid consistency. The variables’ composite dependability is higher than the suggested value of 0.70 (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994).

The fit between the proposed model and the observed covariance matrix was assessed using the goodness-of-fit index (GFI), which yielded a value of 0.868. The model displays 276 unique sample moments and requires the estimation of 55 unique parameters. With a probability level of 0.000 and a Chi-square total of 320.167 with 221 degrees of freedom, the CMIN/DF is 1.449. The Chi-squared test indicates the difference between the observed and anticipated covariance matrices (Byrne, 2013).

The model’s dependability was validated using the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). The model is supported by 0.075 since the literature states that the maximum is 0.08 (Bentler, 1990). As demonstrated in Table 3, the baseline comparisons’ fit indices indicate that the proposed model fits the observed variance–covariance matrix more closely than the null or independent model. Bentler and Bonett (1980) state that the Baseline Comparison indices are higher than the predetermined cutoff point of 0.7.

Table 3.

Baseline Comparisons.

3. Results

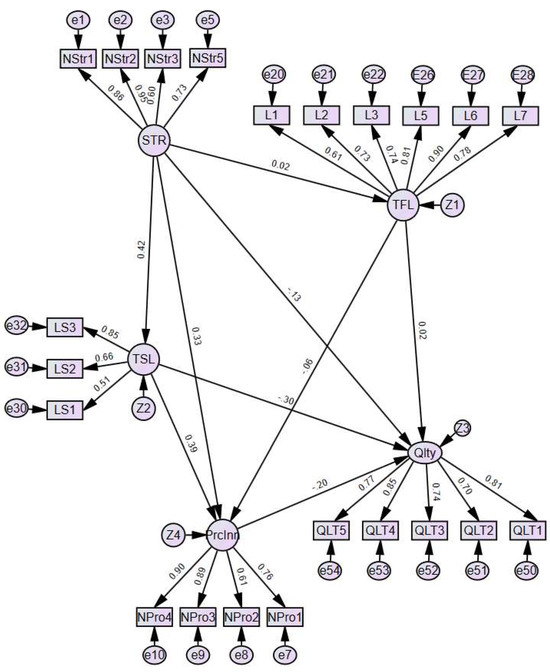

The Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) analysis provided several insights into the relationships between strategic variables and their impacts on transformational leadership (TFL), transactional leadership (TSL), process innovation (PrcInn), and quality (Qlty). The regression weight table (Table 4) details these relationships and their statistical significance:

Table 4.

Regression Weights.

- Transformational Leadership (TFL) and Strategy (STR):

The relationship between TFL and STR was found to be non-significant (Estimate = 0.011, S.E. = 0.046, C.R. = 0.236, p = 0.814), leading to the rejection of Hypothesis H1. This indicates that strategic initiatives do not significantly influence transformational leadership within the sampled data.

- Transactional Leadership (TSL) and Strategy (STR):

A significant positive relationship was observed between TSL and STR (Estimate = 0.292, S.E. = 0.072, C.R. = 4.068, p < 0.001), confirming Hypothesis H2. This suggests that strategic approaches are positively associated with the adoption of transactional leadership styles.

- Process Innovation (PrcInn) and Strategy (STR):

The analysis revealed a significant positive relationship between PrcInn and STR (Estimate = 0.311, S.E. = 0.078, C.R. = 3.984, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis H3. This indicates that strategic initiatives strongly predict process innovation within organizations.

- Process Innovation (PrcInn) and Transformational Leadership (TFL):

The relationship between PrcInn and TFL was not significant (Estimate = −0.101, S.E. = 0.114, C.R. = −0.881, p = 0.378), leading to the rejection of Hypothesis H5. This finding suggests that transformational leadership does not significantly influence process innovation.

- Process Innovation (PrcInn) and Transactional Leadership (TSL):

A significant positive relationship was found between PrcInn and TSL (Estimate = 0.533, S.E. = 0.140, C.R. = 3.794, p < 0.001), confirming Hypothesis H6. This suggests that transactional leadership positively impacts process innovation efforts.

- Quality (Qlty) and Strategy (STR):

The relationship between Qlty and STR was found to be non-significant (Estimate = −0.076, S.E. = 0.051, C.R. = −1.487, p = 0.137), leading to the rejection of Hypothesis H4. This indicates that strategic initiatives do not significantly affect quality outcomes directly.

- Quality (Qlty) and Transformational Leadership (TFL):

The relationship between Qlty and TFL was not significant (Estimate = 0.015, S.E. = 0.074, C.R. = 0.205, p = 0.837), leading to the rejection of Hypothesis H8. This finding suggests that transformational leadership does not significantly influence quality outcomes.

- Quality (Qlty) and Transactional Leadership (TSL):

A significant negative relationship was observed between Qlty and TSL (Estimate = −0.251, S.E. = 0.091, C.R. = −2.746, p = 0.006), confirming Hypothesis H7. This indicates that higher levels of transactional leadership are associated with lower-quality outcomes.

- Quality (Qlty) and Process Innovation (PrcInn):

The relationship between Qlty and PrcInn was partially confirmed with a near-significant negative relationship (Estimate = −0.119, S.E. = 0.060, C.R. = −1.967, p = 0.049), leading to partial confirmation of Hypothesis H9. This suggests that process innovation may have a complex and nuanced impact on quality, requiring further investigation Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Structural model.

The study’s findings present a complex relationship between strategic innovation, leadership styles, and operational quality within manufacturing organizations in Colombia. While strategic innovation significantly enhances transactional leadership and process innovation, it does not impact transformational leadership or improve operational quality. This divergence from existing literature underscores a critical need for enhanced leadership development programs that can effectively integrate innovative strategies.

4. Discussion

This study sought to loosen the complexities surrounding the relationships between strategic innovation, leadership styles, process innovation, and operational quality in Colombian manufacturing organizations. Our findings contribute to the ongoing dialogue by challenging existing assumptions about the direct and often oversimplified connections between these constructs, offering a deeper understanding of their interactions. The non-significant relationship between strategic innovation and transformational leadership is particularly striking. This finding challenges the conventional wisdom that strategic innovation automatically fosters visionary, change-oriented leadership (Bass & Avolio, 1990). Transformational leadership, which is typically associated with inspiring and motivating employees toward innovative changes, did not show a direct link to strategic innovation in this context. This suggests that strategic innovation initiatives in Colombian manufacturing organizations may not yet align with the leadership type required to drive visionary change. It is possible that the existing organizational structures or cultural factors may not fully support the transformative leadership behaviors necessary for fostering large-scale innovation (Kotter, 2008). Therefore, there is a need for tailored leadership development programs that not only focus on enhancing transactional behaviors but also inspire transformational change in these settings. Conversely, the study revealed a strong positive relationship between transactional leadership and strategic innovation. This finding aligns with recent research by (Alrowwad et al., 2020), underscoring the importance of transactional leadership in ensuring that innovation strategies are executed efficiently and effectively. In the context of process innovation, transactional leadership’s focus on structure, performance accountability, and results-driven behaviors seems to be a vital enabler. Transactional leaders create an environment where employees are motivated to pursue incremental improvements and adhere to defined procedures, which can be essential for optimizing operational processes. This study, therefore, highlights the importance of transactional leadership in facilitating process innovation, particularly in developing countries where the emphasis on efficiency and cost reduction is paramount. However, the anticipated improvements in operational quality were not uniformly observed across all leadership styles and innovation processes. The negative relationship between transactional leadership and operational quality suggests that while transactional leadership may drive process efficiencies, it does not always translate into higher-quality outcomes. This finding calls attention to the complexities of implementing innovation strategies in manufacturing organizations. While transactional leadership may help streamline operations, it can sometimes overlook the broader strategic focus on continuous improvement and quality enhancement (Wang et al., 2011). Furthermore, the partial confirmation of the relationship between process innovation and operational quality indicates that while process innovation can enhance quality, the process is not always straightforward. The impact of innovation on quality may depend on the nature of the innovation, its implementation, and the specific organizational context (Molina-Azorín et al., 2015). An essential contribution of this study lies in its consideration of the organizational context, guided by Oc (2018)’s integrative framework. This framework underscores the critical role of contextual factors in shaping leadership behaviors and their outcomes. The findings highlight that leadership effectiveness cannot be understood in isolation from the broader organizational environment. In the case of Colombian manufacturing firms, contextual factors such as organizational culture, industry dynamics, and external market pressures likely influence the leadership styles that are most effective in driving innovation and quality outcomes. This aligns with the notion that leadership is not simply a matter of individual traits or behaviors but is deeply embedded in the context in which it operates (Oc, 2018). Therefore, this study challenges the one-size-fits-all approach to leadership and innovation, proposing that leadership strategies and innovation practices must be tailored to the organization’s specific context. In particular, the Colombian manufacturing context calls for a more nuanced approach to leadership development—one that accounts for the cultural and structural realities of these organizations. By integrating transformational and transactional leadership approaches, organizations can more effectively balance the implementation of innovation strategies and demands of operational efficiency.

5. Conclusions

Strategic innovation’s positive effect on transactional leadership suggests that organizations adopt more structured and results-oriented leadership styles to drive process innovation. This is further supported by the significant positive relationship between process innovation and transactional leadership. However, the non-significant relationship between strategic innovation and transformational leadership indicates that current strategic initiatives may not foster the visionary and change-oriented leadership necessary for transformational growth.

Despite these advancements in leadership and process innovation, the anticipated improvements in operational quality were not observed. The negative relationship between transactional leadership and quality outcomes, along with the complex impact of process innovation on quality, highlights potential inefficiencies and misalignments in how innovation strategies are implemented. These results suggest that while strategic innovation drives certain types of leadership and process improvements, it does not automatically translate into better operational quality. Therefore, manufacturing organizations in Colombia must reassess their innovation strategies and leadership development programs to ensure they are fostering the right conditions for both innovation and quality enhancement.

The study’s findings offer several implications for both theory and practice. From a theoretical perspective, it expands our understanding of the relationships between leadership styles, strategic innovation, and operational quality in a developing economy context. From a practical standpoint, it suggests that manufacturing organizations in Colombia should reassess their innovation strategies and leadership development programs to ensure they are aligned with both strategic goals and operational realities. Future research should explore how contextual factors—such as industry-specific challenges and organizational culture—affect leadership and innovation outcomes, with particular attention to the role of leadership in driving sustained competitive advantage in developing markets.

6. Limitations

This study has some limitations to consider. We used a convenience sample of respondents selected based on their role, knowledge, experience, and ability. Additionally, the sample size was small compared to extensive quantitative studies in other countries. However, our research provides valuable insights that justify more comprehensive studies in the future. The findings, therefore, should be interpreted with caution when applying them to broader contexts or different types of organizations. Second, the study’s reliance on self-reported data from managers and employees may introduce biases, particularly in measuring leadership styles and innovation behaviors. Although steps were taken to minimize social desirability bias, respondents’ subjective perceptions of leadership and innovation may not always reflect objective organizational outcomes. Future research could benefit from incorporating multiple data sources, such as peer evaluations or performance metrics, to provide a more comprehensive view of leadership behaviors and their impact on innovation and quality outcomes. Finally, while the study’s cross-sectional design provides valuable insights into the relationships between the variables, it does not allow for causal inferences. Longitudinal studies would be valuable in examining how leadership styles and strategic innovation initiatives evolve and how they interact with organizational outcomes such as operational quality. Longitudinal data could also shed light on the long-term impacts of different leadership approaches on innovation and quality in manufacturing organizations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S., and R.Z.-T.; methodology, R.S., R.Z.-T., and C.F.R.-S.; software, R.S.; validation, R.S., R.Z.-T., C.F.R.-S., and D.M.; formal analysis, R.S.; investigation, R.S., R.Z.-T., C.F.R.-S., and D.M.; resources, R.S., R.Z.-T., and C.F.R.-S.; data curation, R.S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S., R.Z.-T., and C.F.R.-S.; writing—review and editing, R.Z.-T., and C.F.R.-S.; visualization, R.S., R.Z.-T., C.F.R.-S., and D.M.; supervision, R.S., and R.Z.-T.; project administration, C.F.R.-S.; funding acquisition, R.S., R.Z.-T., and C.F.R.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Colegio de Estudios Superiores de Administracion Ethics Committee ID 002 approved it on 1 September 2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

This paper provides material available in the following repository (https://repository.cesa.edu.co/handle/10726/4947) accessed on 1 December 2023.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Colegio de Estudios Superiores de Administración in Bogotá, Colombia, for providing the tools and facilities to write this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alrowwad, A., Abualoush, S. H., & Masa’deh, R. (2020). Innovation and intellectual capital as intermediary variables among transformational leadership, transactional leadership, and organizational performance. Journal of Management Development, 39(2), 196–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Taneiji, S. (2006). Transformational leadership and teacher learning in model schools. Journal of Faculty of Education UAEU, 23(6), 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Asbari, M., Santoso, P. B., & Prasetya, A. B. (2020). Elitical and antidemocratic transformational leadership critics: Is it still relevant? (A literature study). International Journal of Social, Policy and Law, 1(1), 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Audretsch, D. B. (1995). Innovation, growth and survival. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 13(4), 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltaci, A., & Balcı, A. (2017). Complexity leadership: A theorical perspective. International Journal of Educational Leadership and Management, 5(1), 30–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-On, R. (2006). The Bar-On model of emotional-social intelligence (ESI) 1. Psicothema, 18, 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera, K. G., & Shah, D. (2023). Marketing in the Metaverse: Conceptual understanding, framework, and research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 155, 113420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B. M. (1997). Personal selling and transactional/transformational leadership. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 17(3), 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1990). Developing transformational leadership: 1992 and beyond. Journal of European Industrial Training, 14(5), 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1993). Transformational leadership and organizational culture. Public Administration Quarterly, 17, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benamati, J. S., Serva, M. A., & Fuller, M. A. (2010). The productive tension of trust and distrust: The coexistence and relative role of trust and distrust in online banking. Journal of Organizational Computing and Electronic Commerce, 20(4), 328–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, T. M. (2009). A study of the management leadership style preferred by IT subordinates. Journal of Organizational Culture, 13(2), 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88(3), 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, H., Kuhn, J., & Gertsen, F. (2006). Continuous innovation: Managing dualities through co-ordination. CINet Working Paper Series. Continuous Innovation Network. [Google Scholar]

- Bordella, D., Liu, M., Ravarini, R., Wu, A., & Nigam, F. Y. (2011, June 20–21). Towards a method for realizing sustained competitive advantage through business entity analysis. International Workshop on Business Process Modeling, Development and Support, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Brigham, E., & Ehrhardt, M. (2016). Financial management (12th ed.). Thomson South-Western. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S. L., & Eisenhardt, K. M. (1995). Product development: Past research, present findings, and future directions. Academy of Management Review, 20(2), 343–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruch, H., & Walter, F. (2007). Leadership in context: Investigating hierarchical impacts on transformational leadership. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 28(8), 710–726. [Google Scholar]

- Bycio, P., Hackett, R. D., & Allen, J. S. (1995). Further assessments of Bass’s (1985) conceptualization of transactional and transformational leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80(4), 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B. M. (2013). Structural equation modeling with mplus: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural equation modeling with AMOS—Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, J. C. D. A., & Madeira, M. J. (2021). Critical factors of innovation in Brazilian firms. International Journal of Technology, Policy and Management, 21(3), 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cefis, E., Coad, A., & Lucini-Paioni, A. (2023). Landmarks as lighthouses: Firms’ innovation and modes of exit during the business cycle. Research Policy, 52(8), 104778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cefis, E., & Marsili, O. (2006). Survivor: The role of innovation in firms’ survival. Research Policy, 35(5), 626–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W. W. (2010). How to write up and report PLS analyses in handbook of partial least squares. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Cinnioğlu, H., Atay, L., & Susnienė, D. (2020). Relationship between transactional leadership, transformational leadership, and job satisfaction: Research in food and beverage enterprises. Taikomieji Tyrimai Studijose ir Praktikoje—Applied Research in Studies and Practice, 16, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Cooksey, R. (2007). Illustrating statistical procedures for business, behavioural & social science research. Tilde University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cortes, A. F., & Herrmann, P. (2021). Strategic leadership of innovation: A framework for future research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 23(2), 224–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černe, M., Jaklič, M., & Škerlavaj, M. (2013). Authentic leadership, creativity, and innovation: A multilevel perspective. Leadership, 9(1), 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, T. (1993). Process innovation: Reengineering work through information technology. Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Den Hartog, D. N., VAN Muijen, J. J., & Koopman, P. L. (1997,Transactional versus transformational leadership: An analysis of the MLQ. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 70(1), 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervitsiotis, K. N. (2010,Developing full-spectrum innovation capability for survival and success in the global economy. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 21(2), 159–170. [Google Scholar]

- Dosi, G. (1988). Sources, procedures, and microeconomic effects of innovation. Journal of Economic Literature, 26, 1120–1171. [Google Scholar]

- Drucker, P. F. (1985). Entrepreneurial strategies. California Management Review, 27(2), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvouletý, O. (2018). How to analyse determinants of entrepreneurship and self-employment at the country level? A methodological contribution. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 9, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edquist, C. (2001, June 12–15). The systems of innovation approach and innovation policy: An account of the state of the art. DRUID Conference, Aalborg, Denmark. [Google Scholar]

- Ettlie, J. E., & Reza, E. M. (1992). Organizational integration and process innovation. Academy of Management Journal, 35(4), 795–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, R., & Vezzani, A. (2010). The economic impact of technological and organizational innovations. A firm-level analysis. Research Policy, 39(10), 1253–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M. P., Serra, F. R., Costa, B. K., & Almeida, M. (2016). A bibliometric study of the resource-based view (RBV) in international business research using barney (1991) as a key marker. Innovar, 26(61), 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, T. (2006). Rethinking and reinventing Michael Porter’s five forces model. Strategic Change, 15(5), 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumusluoglu, L., & Ilsev, A. (2009). Transformational leadership, creativity, and organizational innovation. Journal of Business Research, 62(4), 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., Black, W. C., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective. Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, M. (2004). Deep change: How operational innovation can transform your company. IEEE Engineering Management Review, 32(3), 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, M., & Champy, J. (1993). Business process reengineering (Vol. 444). Nicholas Brealey. [Google Scholar]

- Hendel, R. J. (2017). Leadership for improving student success through higher cognitive instruction. In Comprehensive Problem-Solving and skill development for Next-Generation leaders (pp. 230–254). IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Hoe, S. L. (2006). Tacit knowledge, nonaka and takeuchi seci model and informal knowledge processes. International Journal of Organization Theory & Behavior, 9(4), 490–502. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, J. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1993). Transformational leadership, transactional leadership, locus of control, and support for innovation: Key predictors of consolidated-business-unit performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(6), 891–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D. J., Lee, A., Tian, A. W., Newman, A., & Legood, A. (2018). Leadership, creativity, and innovation: A critical review and practical recommendations. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(5), 549–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indah, R., Sarwoko, E., Arief, M., & Nurdiana, I. (2021). Marketing Investigation: Customer Relationship Management and Innovation to Improve Competitive Advantage and Business Performance. Humanities, 9(4), 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J. J., Vera, D., & Crossan, M. (2009). Strategic leadership for exploration and exploitation: The moderating role of environmental dynamism. The Leadership Quarterly, 20(1), 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, F., Grisaffe, D. B., Chonko, L. B., & Roberts, J. A. (2009). Examining the impact of servant leadership on sales force performance. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 29(3), 257–275. [Google Scholar]

- Jha, S. (2014). Transformational leadership and psychological empowerment: Determinants of organizational citizenship behavior. South Asian Journal of Global Business Research, 3(1), 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong, J. P. J. (2007). Individual Innovation: The connection between leadership and employees’ innovative work behavior [Ph.D. Thesis, EIM Amsterdam]. [Google Scholar]

- Kafetzopoulos, D., & Skalkos, D. (2019). An audit of innovation drivers: Some empirical findings in Greek agri-food firms. European Journal of Innovation Management, 22(2), 361–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, K. B. (2018). Understanding innovation. Business Horizons, 61(3), 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koc, T., & Ceylan, C. (2007). Factors impacting the innovative capacity in large-scale companies. Technovation, 27(3), 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotter, J. P. (2008). Force for change: How leadership differs from management. Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Lambardí, G. D., & Mora, J. J. (2014). Determinantes de la innovación en productos o procesos: El caso colombiano. Revista de Economía Institucional, 16(31), 251–262. [Google Scholar]

- Lappalainen, L., Aleem, M., & Sandberg, B. (2023). How to manage open innovation projects? An integrative framework. Project Leadership and Society, 4(2), 100095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leban, W., & Zulauf, C. (2004). Linking emotional intelligence abilities and transformational leadership styles. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 25(7), 554–564. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, D., & Slocum, J. W. (2005). Strategic and organizational requirements for competitive advantage. Academy of Management Perspectives, 19(1), 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundvall, B. A. (1992). National systems of innovation: Towards a theory of innovation and interactive learning (Vol. 242). London Pinter. [Google Scholar]

- Luoto, S., Brax, S. A., & Kohtamäki, M. (2017). Critical meta-analysis of servitization research: Constructing a model-narrative to reveal paradigmatic assumptions. Industrial Marketing Management, 60, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, S. B., Podsakoff, P. M., & Rich, G. A. (2001). Transformational and transactional leadership and salesperson performance. Journal of the academy of Marketing Science, 29, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Azorín, J. F., Tarí, J. J., Pereira-Moliner, J., López-Gamero, M. D., & Pertusa-Ortega, E. M. (2015). The effects of quality and environmental management on competitive advantage: A mixed methods study in the hotel industry. Tour Manager, 50, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouazen, A. M., Hernández-Lara, A. B., Abdallah, F., Ramadan, M., Chahine, J., Baydoun, H., & Bou Zakhem, N. (2023). Transformational and Transactional Leaders and Their Role in Implementing the Kotter Change Management Model Ensuring Sustainable Change: An Empirical Study. Sustainability, 16(1), 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachtigall, C., Kroehne, U., Funke, F., & Steyer, R. (2003). Pros and cons of structural equation modeling. Methods Psychological Research Online, 8(2), 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Namnai, K., Ussahawanitchakit, P., & Janjarasjit, S. (2015). Modern cost management innovation and performnce: A Conceptual Model. In Allied academies international conference. Academy of accounting and financial studies. Proceedings (Vol. 20, p. 107). Jordan Whitney Enterprises, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Nasir, A., Zakaria, N., & Zien Yusoff, R. (2022). The influence of transformational leadership on organizational sustainability in the context of industry 4.0: Mediating role of innovative performance. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2105575. [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka, L., Takeuchi, H., & Umemoto, K. (1996). A theory of organizational knowledge creation. International Journal of Technology Management, 11(7–8), 833–845. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychological theory. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Oc, B. (2018). Contextual leadership: A systematic review of how contextual factors shape leadership and its outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(1), 218–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Dias, D. D., Maqueira Marín, J. M., & Moyano-Fuentes, J. (2022). Lean and agile supply chain strategies: The role of mature and emerging information technologies. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 33(5), 221–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P., & Pavitt, K. (1994). National innovation systems: Why they are important, and how they might be measured and compared. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 3(1), 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N. P., Podsakoff, P. M., & Kuskova, V. V. (2010). Dispelling misconceptions and providing guidelines for leader reward and punishment behavior. Business Horizons, 53(3), 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Moorman, R. H., & Fetter, R. (1990). Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers’ trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Business Strategy, 1(2), 107–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. E. (1985). Technology and competitive advantage. Journal of Business Strategy, 5(3), 60–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. E. (1996). Operational effectiveness is not strategy. Harvard Business Review, 74(6), 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Prabhu, H. M., & Srivastava, A. K. (2023). CEO transformational leadership, supply chain agility and firm performance: A TISM modeling among SMEs. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 24(1), 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajogo, D. I., & Sohal, A. S. (2003). The relationship between TQM practices, quality performance, and innovation performance: An empirical examination. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 20(8), 901–918. [Google Scholar]

- Quinhões, T. A. T., & Lapão, L. V. (2023). Innovation management: Still a long way to go (Vol. 64). No. 1. SciELO Brasil. [Google Scholar]

- Ratten, V., & Ferreira, J. (2017). Entrepreneurship, innovation and sport policy: Implications for future research. International Journal of Sport Policy, 9(4), 575–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejeb, H. B., Morel-Guimarães, L., Boly, V., & Assiélou, N. G. (2008). Measuring innovation best practices: Improvement of an innovation index integrating threshold and synergy effects. Technovation, 28(12), 838–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, A., & Hussain Haider, M. (2010). Role of transformational and transactional leadership on job satisfaction and career satisfaction. Business and Economic Horizons, 1, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa, R., Ferrer, M., Bretherton, P., & Hyland, P. (2009). The necessary alignment between technology innovation effectiveness and operational effectiveness. Journal of Management & Organization, 15(2), 155–169. [Google Scholar]

- Santa, R., Hyland, P., & Ferrer, M. (2014). Technological innovation and operational effectiveness: Their role in achieving performance improvements. Production Planning & Control, 25(12), 969–979. [Google Scholar]

- Santa, R., MacDonald, J. B., & Ferrer, M. (2019). The role of trust in e-Government effectiveness, operational effectiveness and user satisfaction: Lessons from Saudi Arabia in e-G2B. Government Information Quarterly, 36(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A. N. (2013). Promoting eco-innovations to leverage sustainable development of eco-industry and green growth. European Journal of Sustainable Development, 2(1), 171–171. [Google Scholar]

- Shane, S. (2002). The foundations of entrepreneurship. McGraw Hill Irwin. [Google Scholar]

- Skopak, A., & Hadzaihmetovic, N. (2022). The impact of transformational and transactional leadership style on employee job satisfaction. International Journal of Business and Administrative Studies, 8(3), 113–126. [Google Scholar]