Material Deprivation, Institutional Trust, and Mental Well-Being: Evidence from Self-Employed Europeans

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Evidence on Material Deprivation, Trust, and Well-Being in General Population

2.2. Evidence from Studies on Self-Employed Individuals

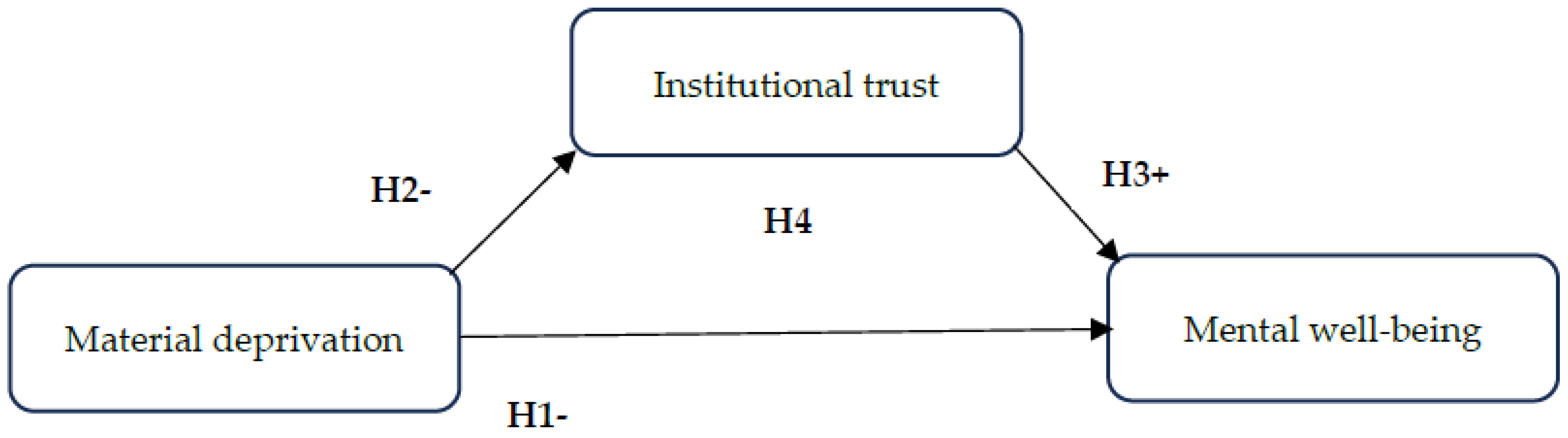

2.3. Research Model

3. Methodology

Data and Sample

4. Measures

Method of Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Model Validation

5.2. Descriptive Statistics

5.3. Hypothesis Testing

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2. Comparison with Prior Research

6.3. Practical Implications

6.4. Limitations and Further Research

6.5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. EQLS Items and Scale Item Selection for the Measures of Mental Well-Being, Material Deprivation, and Institutional Trust

- (1)

- The independent variable, material deprivation, originally contained six items as follows:

- (a)

- ‘Affording keeping home adequately warm’.

- (b)

- ‘Affording paying for holiday’.

- (c)

- ‘Affording replacing old furniture’.

- (d)

- ‘Affording meal with meat, chicken, fish if wanted’.

- (e)

- ‘Affording buying new clothes’.

- (f)

- ‘Affording having friends or family for a drink or meal once a month’.

- (2)

- The dependent variable, mental well-being, made use of all the available items focused on positive affect, vigour, and energy, in line with our conceptualisation of the concept.

- (a)

- I have felt cheerful and in good spirits.

- (b)

- I have felt calm and relaxed.

- (c)

- I have felt active and vigorous.

- (d)

- I woke up feeling fresh and rested.

- (e)

- My daily life has been filled with things that interest me.

- (3)

- Mediator variable, institutional trust.The question about trust contained eight statements related to trust, as follows:

- (a)

- Trust in parliament.

- (b)

- Trust in the legal system.

- (c)

- Trust in the news media.

- (d)

- Trust in the police.

- (e)

- Trust in the government.

- (f)

- Trust in the local (municipal) authorities.

- (g)

- Trust in banks.

- (h)

- Trust in humanitarian or charitable organisations.

| 1 | The methodological focus of this study was to explain and predict the variance in endogenous constructs rather than optimise global covariance-based model fit, which an alternative SEM analysis package, SPSS AMOS, is concerned with (Hair et al., 2019). In addition, SmartPLS adequately handles different Likert-type and potentially non-normally distributed indicators and offers a straightforward bootstrapping procedure for estimating indirect (mediated) effects and their bias-corrected confidence intervals. The relatively large sample size can further increase the precision and stability of the PLS-SEM estimates as well as the bootstrapped mediation results. |

| 2 | The autonomy measure was based on the respondents’ assessment of their agreement with the statement ‘I feel I am free to decide how to live my life’ using a 5-point Likert scale. |

References

- Bi, S., Maes, M., Stevens, G. W., de Heer, C., Li, J. B., Sun, Y., & Finkenauer, C. (2025). Trust and subjective well-being across the lifespan: A multilevel meta-analysis of cross-sectional and longitudinal associations. Psychological Bulletin, 151, 737–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billah, M. A., Akhtar, S., & Khan, M. N. (2023). Loneliness and trust issues reshape mental stress of expatriates during early COVID-19: A structural equation modelling approach. BMC Psychology, 11(1), 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobzien, L. (2023). Income inequality and political trust: Do fairness perceptions matter? Social Indicators Research, 169(1), 505–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K. A., & Pearl, J. (2013). Eight myths about causality and structural equation models. In Handbook of causal analysis for social research (pp. 301–328). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Bornand, T., & Klein, O. (2022). Political trust by individuals of low socioeconomic status: The key role of anomie. Social Psychological Bulletin, 17, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corradini, C. (2022). Social trust and new firm formation: A regional perspective. Small Business Economics, 58(1), 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cribb, J., & Xu, X. (2020). Going solo: How starting solo self-employment affects incomes and well-being (IFS working paper No. W20/23). Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS).

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 49(3), 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egamberdiev, B., Bobojonov, I., & Kuhn, L. (2025). Institutional trust and subjective well-being in post-soviet countries. Comparative Economic Studies, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrin, S., Mickiewicz, T., & Stephan, U. (2013). Entrepreneurship, social capital, and institutions: Social and commercial entrepreneurship across nations. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(3), 479–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound. (2017). Exploring self-employment in the European Union. Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/all/exploring-self-employment-european-union (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Eurofound (European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions). (2018a). European quality of life survey integrated data file, 2003–2016 (3rd Release, SN: 7348) [data collection]. UK Data Service. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound (European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions). (2018b). Societal change and trust in institutions. Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/all/societal-change-and-trust-institutions (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Eurofound (European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions). (2022a). European quality of life survey 2020: Living, working and COVID-19. Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound (European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions). (2022b). Maintaining trust during the COVID-19 pandemic. Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/all/maintaining-trust-during-covid-19-pandemic (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- European Trade Union Institute (ETUI). (2021). Social protection of non-standard workers and the self-employed during the pandemic (country chapters). ETUI. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, N. J., & Klein, P. G. (2020). Entrepreneurial opportunities: Who needs them? Academy of Management Perspectives, 34(3), 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gashi, A., Krasniqi, B., Ramadani, V., & Berisha, G. (2024). Evaluating the impact of individual and country-level institutional factors on subjective well-being among entrepreneurs. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 9(2), 100486. [Google Scholar]

- Gokmen, S., Dagalp, R., & Kilickaplan, S. (2020). Multicollinearity in measurement error models. Communication in Statistics—Theory and Methods, 51(2), 474–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halleröd, B., & Larsson, D. (2008). Poverty, welfare problems and social exclusion. International Journal of Social Welfare, 17(1), 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hann, C. (2010). Moral economy. In K. Hart, J. L. Laville, & A. D. Cattani (Eds.), The human economy: A citizen’s guide (pp. 187–198). Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, S. M., & Sandal, G. M. (2021). COVID-19 and psychological distress in Norway: The role of trust in the healthcare system. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 49(1), 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helliwell, J. F., Huang, H., & Wang, S. (2016). New evidence on trust and well-being (No. w22450). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Henseler, J., & Sarstedt, M. (2013). Goodness-of-fit indices for partial least squares path modeling. Computational Statistics, 28(2), 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooghe, M., & Dassonneville, R. (2018). A spiral of distrust: A Panel study on the relation between political distrust and protest voting in Belgium. Government and Opposition, 53(1), 104–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horemans, J., & Marx, I. (2024). Poverty, inequality and material deprivation among the self-employed in Europe. In Research handbook on self-employment and public policy (pp. 80–98). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, D. K., Simmons, S. A., & Wieland, A. M. (2017). Designing entrepreneurship experiments: A review, typology, and research agenda. Organizational Research Methods, 20(3), 379–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, J. (2006). Institutional trust and subjective well-being across the EU. Kyklos, 59(1), 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. H.-S. (2023). Psychological distress and political distrust during a global health crisis: Evidence from a cross-national survey. Political Studies Review, 21(4), 639–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumlin, S., & Haugsgjerd, A. (2017). The welfare state and political trust: Bringing performance back in. In Handbook on political trust (pp. 285–301). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. (2022). Subjective well-being and mental health during the pandemic outbreak: Exploring the role of institutional trust. Research on Aging, 44(1), 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marien, S., & Hooghe, M. (2011). Does political trust matter? An empirical investigation of the relation between political trust and support for democracy. European Journal of Political Research, 50(2), 267–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, B., & Walsh, E. (2023). A happy home? Socio-economic inequalities in depressive symptoms and the role of housing quality in nine European countries. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKay, L., Jennings, W., & Stoker, G. (2021). Political trust in the “places that don’t matter”. Frontiers in Political Science, 3, 642236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullen, J. (2017). Are we confounding heroism and individualism? Entrepreneurs may not be lone rangers, but they are heroic nonetheless. Business Horizons, 60(1), 257–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narotzky, S., & Besnier, N. (2014). Crisis, value, and hope: Rethinking the economy: An introduction to supplement 9. Current Anthropology, 55(S9), S4–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaev, B. N., Boudreaux, C. J., & Palich, L. (2019). Cross-country determinants of early-stage necessity and opportunity-motivated entrepreneurship: Accounting for model uncertainty. Journal of Small Business Management, 56, 243–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordenmark, M., Landstad, B. J., Tjulin, Å., & Vinberg, S. (2023). Life satisfaction among self-employed people in different welfare regimes during the COVID-19 pandemic: Significance of household finances and concerns about work. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), 5141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obadia, C., & Vida, I. (2011). Cross-border relationships and performance: Revisiting a complex linkage. Journal of Business Research, 64, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2017). Trust and public policy: How better governance can help rebuild public trust. OECD Public Governance Reviews. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2021). How’s life? Measuring well-being (2021 ed.). OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2022). Building trust to reinforce democracy: Main findings from the 2021 OECD survey on drivers of trust in public institutions. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., Podsakoff, N. P., Williams, L. J., Huang, C., & Yang, J. (2024). Common method bias: It’s bad, it’s complex, it’s widespread, and it’s not easy to fix. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 11(1), 17–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Becker, J. -M. (2024). SmartPLS 4. SmartPLS. Available online: https://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Hair, J. F. (2019). Partial least squares structural equation modeling. In C. Homburg, M. Klarmann, & A. Vomberg (Eds.), Handbook of market research (pp. 1–40). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Moreno, E., & Gallardo-Peralta, L. P. (2022). Income inequalities, social support and depressive symptoms among older adults in Europe: A multilevel cross-sectional study. European Journal of Ageing, 19(3), 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shir, N., Nikolaev, B. N., & Wincent, J. (2019). Entrepreneurship and well-being: The role of psychological autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(5), 105875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisu, J. A., Tirnovanu, A. C., Patriche, C.-C., Nastase, M., & Schin, G. C. (2023). Enablers of students’ entrepreneurial intentions: Findings from PLS-SEM and fsQCA. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 30(4), 856–884. [Google Scholar]

- Slimmen, S., Timmermans, O., Mikolajczak-Degrauwe, K., & Oenema, A. (2022). How stress-related factors affect mental wellbeing of university students A cross-sectional study to explore the associations between stressors, perceived stress, and mental wellbeing. PLoS ONE, 17(11), e0275925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorgner, A., Fritsch, M., & Kritikos, A. (2014). Do entrepreneurs really earn less? Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/100449/1/VfS_2014_pid_399.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Spasova, S., & Regazzoni, P. (2022). Income protection for self-employed and non-standard workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Social Security Review, 75(2), 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephan, U. (2018). Entrepreneurs’ mental health and well-being: A review and research agenda. Academy of Management Perspectives, 32(3), 290–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, U., Rauch, A., & Hatak, I. (2023). Happy entrepreneurs? Everywhere? A meta-analysis of entrepreneurship and wellbeing. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 47(2), 553–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, U., Tavares, S. M., Carvalho, H., Ramalho, J. J. S., Santos, S. C., & van Veldhoven, M. (2020). Self-employment and eudaimonic well-being: Energized by meaning, enabled by societal legitimacy. Journal of Business Venturing, 35(6), 106047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, V. F. Y., & Chou, K. L. (2024). An exploratory study on material deprivation and loneliness among older adults in Hong Kong. BMC Geriatrics, 24(1), 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terraneo, M. (2021). Material and social deprivation and well-being among the elderly in Europe. International Journal of Health Services, 51(2), 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Meer, T. W. G., & Zmerli, S. (2017). The deeply rooted concern with political trust. In S. Zmerli, & T. W. G. van der Meer (Eds.), Handbook on political trust (pp. 1–18). Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, Z., Xie, X., Huang, L., Yan, J., Cheng, S., & Xu, A. (2025). The impact of relative deprivation on mental health among middle-aged and older adults in China: A multiple chain mediation model. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 34105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zmerli, S. (2024). Institutions, political attitudes or personal values? A multilevel investigation into the origins of police legitimacy in Europe. In Comparing police organizations (pp. 86–122). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

| Mental Well-Being | Material Deprivation | Institutional Trust | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item Loading | Item Loading | Item Loading | |||

| Item 1 | 0.951 | Item 1 | 0.485 | Item 1 | 0.798 |

| Item 2 | 0.808 | Item 2 | 0.921 | Item 2 | 0.864 |

| Item 3 | 0.494 | Item 3 | 0.804 | Item 3 | 0.746 |

| Item 4 | 0.523 | Item 4 | 0.522 | Item 4 | 0.887 |

| Item 5 | 0.912 | ||||

| Fit indicators: Cronbach’s alpha = 0.880 AVE = 0.581 Rho_c = 0.867 HTMT (inst.trust) = 0.165 | Fit indicators: Cronbach’s alpha = 0.788 AVE = 0.501 Rho_c = 0.789 HTMT (mental well-being) = 0.230 | Fit indicators: Cronbach’s alpha = 0.897 AVE = 0.681 Rho_c = 0.895 HTMT (deprivation) = 0.226 | |||

| Mental Well-Being | Material Deprivation | Institutional Trust | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mental well-being | 0.581 | ||

| Material deprivation | 0.058 | 0.501 | |

| Institutional trust | 0.030 | 0.058 | 0.681 |

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Material deprivation | 0.177 | 0.291 | |||||||||||||||

| 2. Institutional trust | 4.847 | 2.228 | −0.198 ** | ||||||||||||||

| 3. Mental well-being | 4.320 | 0.967 | −0.196 ** | 0.146 ** | |||||||||||||

| 4. Gender | 0.376 | 0.484 | 0.045 * | −0.020 | −0.029 | ||||||||||||

| 5. Respondent age | 46.969 | 11.720 | −0.023 | 0.021 | −0.013 | −0.030 | |||||||||||

| 6. Education level | 2.183 | 0.719 | −0.256 ** | 0.141 ** | 0.107 ** | 0.086 ** | −0.074 ** | ||||||||||

| 7. Marital status: never married | 0.199 | 0.399 | −0.039 | −0.011 | 0.039 | −0.029 | −0.372 ** | 0.096 ** | |||||||||

| 8. Marital status: married (ref.) | 0.636 | 0.481 | 0.028 | 0.032 | 0.009 | −0.050 * | 0.163 ** | −0.087 ** | −0.659 ** | ||||||||

| 9. Marital status: separated | 0.048 | 0.214 | 0.043 * | −0.068 ** | −0.054 ** | 0.013 | 0.029 | −0.035 | −0.112 ** | −0.297 ** | |||||||

| 10. Marital status: widowed | 0.021 | 0.142 | 0.024 | 0.030 | 0.000 | 0.077 ** | 0.155 ** | −0.029 | −0.072 ** | −0.192 ** | −0.033 | ||||||

| 11. Marital status: divorced | 0.096 | 0.295 | −0.036 | −0.002 | −0.027 | 0.075 ** | 0.141 ** | 0.050 * | −0.162 ** | −0.431 ** | −0.073 ** | −0.047 * | |||||

| 12. EU region: west (ref.) | 0.223 | 0.416 | −0.140 ** | 0.124 ** | 0.047 * | −0.007 | 0.085 ** | 0.081 ** | 0.033 | −0.053 * | 0.017 | 0.022 | 0.018 | ||||

| 13. EU region: centre | 0.176 | 0.381 | −0.100 ** | −0.013 | 0.018 | 0.060 ** | −0.058 ** | 0.049 * | −0.014 | 0.006 | −0.047 * | 0.011 | 0.037 | −0.247 ** | |||

| 14. EU region: east | 0.174 | 0.379 | 0.276 ** | −0.024 | −0.054 ** | −0.081 ** | −0.151 ** | −0.126 ** | −0.042 * | 0.088 ** | −0.004 | −0.012 | −0.078 ** | −0.246 ** | −0.212 ** | ||

| 15. EU region: south | 0.282 | 0.450 | 0.061 ** | −0.233 ** | −0.085 ** | 0.040 | 0.016 | −0.085 ** | 0.016 | −0.011 | 0.052 * | −0.019 | −0.033 | −0.335 ** | −0.289 ** | −0.288 ** | |

| 16. EU region: north | 0.146 | 0.353 | −0.102 ** | 0.190 ** | 0.092 ** | −0.020 | 0.104 ** | 0.096 ** | 0.001 | −0.025 | −0.031 | −0.001 | 0.064 ** | −0.221 ** | −0.191 ** | −0.190 ** | −0.259 ** |

| BC 95% CI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | Label | Estimate | SE | Lower | Upper |

| Indirect | ab | −0.057 ** | 0.017 | −0.094 | −0.025 |

| Direct | c’ | −0.495 *** | 0.074 | −0.633 | −0.345 |

| Total | c | −0.552 *** | 0.072 | −0.685 | −0.406 |

| Path estimates | |||||

| Deprivation → Institutional trust | a | −0.611 *** | 0.061 | −0.729 | −0.490 |

| Institutional trust → Mental well-being | b | 0.093 *** | 0.027 | 0.041 | 0.146 |

| Deprivation → Mental well-being | c’ | −0.495 *** | 0.074 | −0.633 | −0.345 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Majoor-Kozlinska, I. Material Deprivation, Institutional Trust, and Mental Well-Being: Evidence from Self-Employed Europeans. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 489. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15120489

Majoor-Kozlinska I. Material Deprivation, Institutional Trust, and Mental Well-Being: Evidence from Self-Employed Europeans. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(12):489. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15120489

Chicago/Turabian StyleMajoor-Kozlinska, Inna. 2025. "Material Deprivation, Institutional Trust, and Mental Well-Being: Evidence from Self-Employed Europeans" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 12: 489. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15120489

APA StyleMajoor-Kozlinska, I. (2025). Material Deprivation, Institutional Trust, and Mental Well-Being: Evidence from Self-Employed Europeans. Administrative Sciences, 15(12), 489. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15120489