1. Introduction

Currently, the phenomenon of digital transformation (DT) is present in the organizational context. Researchers have been analyzing the impacts of DT on organizational management, namely in people management (

Bhat & Sheikh, 2024;

Husen et al., 2024;

Rani Amalia, 2024;

Zhang et al., 2025), in leadership (

Hanandeh et al., 2023;

Saepudin et al., 2024;

Sainger, 2018), in technology (

Alharbi, 2025;

Kaur & Gandolfi, 2023;

Saepudin et al., 2024), and in sustainability (

Machado et al., 2025). In this context, the COVID-19 pandemic hastened DT due to lockdowns and the increasing adoption of telework, which became the most appropriate work model during 2019 to 2021 (

Figueiredo et al., 2022;

Zachariah et al., 2022). Thus, new concerns have emerged, mainly related to the role of the leader in teleworking contexts (

Figueiredo et al., 2022;

Figueiredo & Rodrigues, 2024).

DT has been profoundly redefining work models and the way organizations are led. In addition to promoting new work dynamics, it has also been imposing new challenges on organizational management, highlighting the importance of technology not only as support in the daily operations of companies but as a central element of culture, performance, and team well-being (

Avolio et al., 2014;

Pinto, 2023).

With the consolidation of telework, the need for a new leadership profile emerged: e-leadership (

Avolio et al., 2014). This form of leading, adapted to digital contexts, requires a specific set of competencies—namely, the ability to communicate effectively in technology-mediated environments, to manage geographically dispersed teams, and to use digital tools to coordinate, motivate, and evaluate employee performance (

Van Wart et al., 2018).

Despite the advantages of teleworking and the digital tools that support it, in recent years there has been a global trend of returning to in-person work, especially in large international organizations (

Executive Digest, 2025;

Exame, 2023). This reversal raises questions about the digital maturity of leadership and its ability to maintain a strong organizational culture, even at a distance. E-leadership, in this context, appears as a differentiating factor, since leadership mediated by information technologies is becoming increasingly relevant and distinct within the current administrative environment (

Van Wart et al., 2017). However, leading remotely continues to be a challenge, especially for leaders trained in in-person contexts, who may present difficulties in tasks such as supervising team performance, maintaining trust, and managing virtual collaboration (

Premuzic, 2025;

Pinto, 2023).

Thus, understanding how leaders are adapting—and how this affects the continuity of telework—has become a relevant question, especially in geographies where greater resistance to returning to the office is observed, as is the case in Portugal (

Redação, 2025;

Jornal de Negócios, 2020).

Studying this topic is of particular importance, given the impact that the leadership model can have on talent retention, productivity, and organizational resilience in a world that is increasingly digital (

Nova, 2025).

Despite the growing body of international research on e-leadership and telework, there remains a notable gap in empirical studies that apply and validate the skills for E-Leadership Competencies (SEC) model within the Portuguese organisational context. Existing literature has primarily focused on general leadership behaviours in digital environments, with limited attention to how specific e-leadership competencies influence organisational preferences for telework. This study addresses this gap by empirically testing the SEC model in Portugal, thereby contributing to the contextual adaptation and potential generalisation of the model. The available data suggest that Portugal has maintained a trajectory distinct from other countries, with a growing acceptance of telework by organizations (

Redação, 2025;

Expresso, 2025).

In this context, the present research arises from the need to understand the relationship between the e-leadership competencies of leaders in Portuguese companies and the evolution of the application of the telework regime in the country.

This study contributes to empirically tests the applicability of the SEC model (

Van Wart et al., 2017) in the Portuguese context, offering insights into its cross-cultural adaptability. Identifying which specific e-leadership competencies are most strongly associated with perceived leadership effectiveness in telework settings. Providing evidence on the relationship (or lack thereof) between e-leadership effectiveness and organisational investment in telework and finally offers a validated diagnostic tool for assessing e-leadership competencies, which can inform leadership development and HR practices in digitally transforming organisations.

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of Variables and Scales

The questionnaire items were treated as independent variables, each formulated as a behavioral statement to which respondents indicated their degree of agreement. All variables were measured using a five-point Likert scale, where 1 corresponds to “strongly disagree” and 5 to “strongly agree” (

Likert, 1932).

The variables were organized into six dimensions, in accordance with the SEC model, and the internal consistency of each was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, as in the original reliability analysis of the questionnaire. For each variable, the Cronbach’s alpha value is presented to evaluate its contribution to the internal reliability of the corresponding dimension. All obtained values were above 0.80, indicating high internal consistency, according to the criteria established by

Hair et al. (

2019). The E-Communication dimension was measured through three variables assessing the clarity and openness of electronic communication, the risk of misunderstandings, and the use of diverse digital channels (

Table 3).

The E-Social dimension, which captures the e-leader’s ability to adapt and diversify communication in a socially sensitive and effective way, was evaluated using three variables (

Table 4).

The E-Team dimension was based on three variables reflecting the e-leader’s role in motivating, empowering, and fostering cohesion within remote teams (

Table 5).

The E-Change dimension comprised three variables assessing the e-leader’s use of ICT to plan, monitor, and evaluate organizational changes in telework contexts (

Table 6).

The E-Tech dimension included three variables measuring digital literacy, technological problem-solving ability, and preventive behavior in technology use (

Table 7).

The E-Trust dimension was operationalized through three variables assessing the e-leader’s ability to build trust, promote ethical behavior, and ensure inclusion among team members in virtual settings (

Table 8).

Each dimension included three items, and their average score represented that dimension. These averages were compared to assessing participants’ alignment with an effective e-leader profile.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

To characterize the study variables and verify the assumptions required for subsequent statistical analyses, a descriptive analysis of the data was conducted. For each of the 18 variables corresponding to the dimensions of the SEC model (

Van Wart et al., 2017), measures of central tendency (mean and median), dispersion (standard deviation), range (minimum and maximum values), and skewness and kurtosis coefficients were examined.

The mean scores (

Table 9) of the variables are mostly above the midpoint of the five-point Likert scale (3), indicating a generally positive perception of e-leadership competencies among participants.

Regarding dispersion, the standard deviations range from 0.494 (Communication1) to 0.984 (Tech1), with generally low values, indicating limited variability in responses. This suggests a degree of homogeneity in participants’ perceptions of the assessed competencies.

To assess the normality of the variable distributions, skewness and kurtosis coefficients were analyzed. The most relevant skewness coefficients were found in Communication1 (skewness = 1.261; skewness coefficient = −5.920 > 1.645), Trust2 (skewness = −1.072; skewness coefficient = −5.032 > 1.645), and Trust3 (skewness = −1.200; skewness coefficient = −5.633 > 1.645), suggesting that participants tended to select higher options on the scale, reflecting highly positive perceptions in these domains and agreement with the corresponding statements. Several variables also showed significant negative skewness, such as E-Social1, E-Social2, E-Social3, E-Team2, E-Team3, E-Change2, E-Change3, E-Tech2, and E-Tech3.

Other variables displayed positive skewness, with E-Communication2 being the most notable (skewness = 1.326; skewness coefficient = 6.225 > 1.645). This indicates that most participants selected low response values, as it is a reverse-scored item—meaning they disagreed with the statement about causing misunderstandings, which is a positive indicator of their e-communication competence. Other variables, such as E-Communication3 and E-Tech1, also exhibited positive skewness, consistent with the same logic, as both are reverse-scored items.

Regarding kurtosis, some significant values were identified, for instance, Communication2 (kurtosis = 2.322; kurtosis coefficient = 5.489) and E-Trust3 (kurtosis = 2.081; kurtosis coefficient = 4.919), suggesting that participants’ responses were highly concentrated around a specific value, indicating strong consensus among respondents regarding these variables. Conversely, the variable Trust1 exhibited a significant negative kurtosis (kurtosis = −0.734; kurtosis coefficient = −1.735), indicating greater dispersion around the mean. Although the values do not deviate dramatically from centrality, this less concentrated distribution may reflect more varied interpretations among participants.

Descriptive statistics show a generally strong perception of e-leadership competencies, with data slightly skewed positively. Notable skewness and kurtosis suggest some variables deviate from normality, which should be considered when choosing statistical tests.

A binomial logistic regression was used for the first research question to assess how independent variables affected the likelihood of being an Effective e-leader, since this outcome was dichotomous and normality was not required. For the second question, Fisher’s exact test analyzed categorical variable associations, as it better suited small cell counts than the Chi-square test.

To assess potential multicollinearity among the independent variables included in the regression models, collinearity diagnostics were conducted using Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) and Tolerance values. According to

Hair et al. (

2019), VIF values below 5 and Tolerance values above 0.20 indicate an acceptable level of multicollinearity, suggesting that the independent variables do not exhibit problematic intercorrelations. As shown in

Table 10, all VIF values ranged between 1.06 and 1.21, and Tolerance values ranged from 0.824 to 0.943. These results confirm that multicollinearity is not a concern in the present analysis, and the regression estimates can be considered robust and reliable.

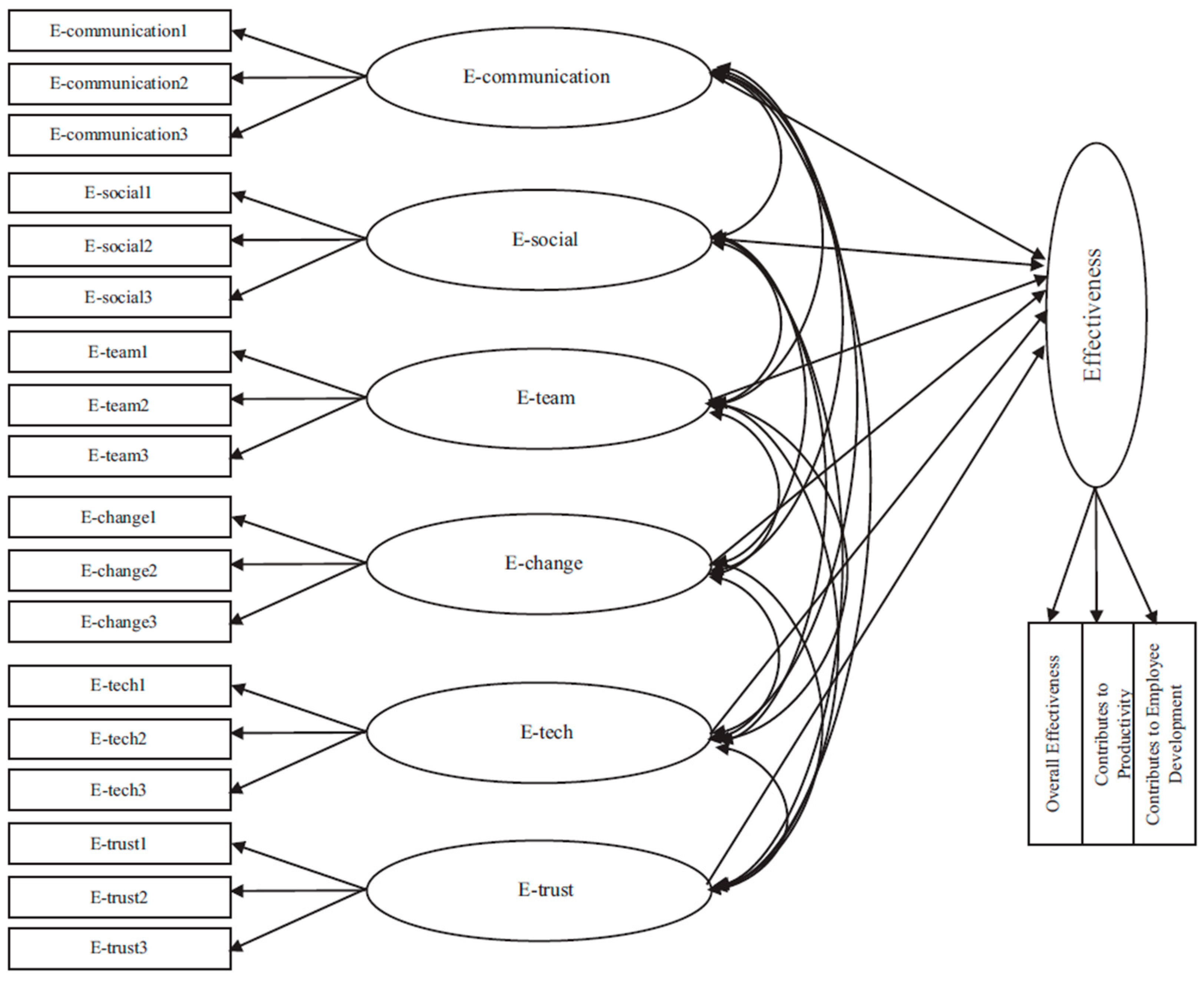

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

As previously mentioned, to address the first research question and test the six proposed hypotheses, a binomial logistic regression was employed, given that the dependent variable—Effective e-Leader—is binary (1 = effective leader; 0 = not effective). Through this test, the influence of independent variables—in this case, the six dimensions of

Van Wart et al.’s (

2017) SEC e-leadership model—on the likelihood of a specific dichotomous outcome of the dependent variable (Effective e-Leader) was examined.

Regarding hypothesis 1.1,

Van Wart et al. (

2017) argued that e-leaders must keep current with effective communication technologies and assess their value to the organization. They should switch between traditional and digital tools as needed and address technology issues promptly, either independently or with support, to maintain team workflow. However, the results of the binomial logistic regression performed in this study (

p = 0.054 > 0.05) show that the E-Tech dimension does not present statistical significance at the 5% level, indicating that there is no significant positive association between this competency and e-leadership effectiveness—contrary to the initial hypothesis. This means that, among the e-leaders surveyed, higher E-Tech skills do not necessarily translate into a greater perception of e-leadership effectiveness.

Concerning hypothesis 1.2,

Van Wart et al. (

2017) argued that communication is a key competency of an effective e-leader, which must be clear, sufficient, and structured to avoid misunderstandings, enabling feedback exchange without becoming excessive. However, the results obtained from the survey conducted in this study (

p = 0.138 > 0.05) provide evidence that the E-Communication dimension does not present statistical significance in the binomial logistic regression model at the 5% level, indicating that no significant positive association was found between this competency and e-leadership effectiveness—contrary to

Van Wart et al.’s (

2017) findings.

Regarding hypothesis 1.3, the E-Social dimension showed statistical significance in the model (

p < 0.001 < 0.05), indicating a positive association between e-leaders’ social competencies and the Effective e-Leader variable at the 5% significance level. Thus, the higher the e-leader’s E-Social competence, the greater the perceived effectiveness of their e-leadership. This result supports

Van Wart et al.’s (

2017) assertion that effective e-leaders provide team support through diverse communication methods (digital or traditional) that are appropriate to individual circumstances.

Concerning hypothesis 1.4, the E-Team dimension showed statistical significance (

p = 0.033 < 0.05), indicating a positive association between e-leaders’ team-building competencies and the Effective e-Leader variable at the 5% significance level. Practically, this means that higher E-Team competence corresponds to a higher perceived effectiveness of e-leadership. This finding aligns with the theoretical framework of

Van Wart et al. (

2017), who argue that an effective e-leader can motivate their team in a virtual environment, reinforce each member’s purpose, and ensure that all team members contribute meaningfully, take responsibility for their work, and are duly recognized and rewarded, as in traditional, face-to-face teams.

Concerning hypothesis 1.5, the E-Change dimension presented statistical significance (

p = 0.006 < 0.05), indicating a positive association between e-leaders’ change management competencies and their perceived e-leadership effectiveness. This result suggests that higher levels of E-Change competence correspond to greater perceived e-leadership effectiveness. This finding supports the theoretical argument of

Van Wart et al. (

2017), who emphasize that e-leaders possessing E-Change competence use effective techniques to manage organizational change through planning, monitoring, and optimizing technology use.

Regarding hypothesis 1.6, the E-Trust dimension did not show statistical significance in the model (

p = 0.287 > 0.05), indicating no significant positive association between e-leaders’ trust-building competencies and the perceived effectiveness of their e-leadership. This finding contrasts with

Van Wart et al. (

2017), who argue that effective e-leaders foster trust by demonstrating honesty, integrity, consistency, and fairness. They ensure their teams feel secure, aware of cybersecurity risks, and confident that personal data are protected. E-leaders balance efficiency with workload management, supporting team members in maintaining work-life balance. Additionally, they promote diversity and inclusion even in virtual contexts, ensuring all members feel supported and represented (

Van Wart et al., 2017).

As discussed, these dimensions significantly increase the likelihood of an e-leader being classified as an Effective e-Leader, suggesting that social, team building, and change-management competencies are key drivers of e-leadership effectiveness.

Conversely, the E-Communication (p = 0.138 > 0.05) and E-Trust (p = 0.287 > 0.05) dimensions did not exhibit statistically significant associations with e-leadership effectiveness, while the E-Tech dimension (p = 0.054 > 0.05) showed a marginal result, suggesting a possible negative trend that did not reach conventional statistical significance at the 5% level.

These results indicate that, among the six dimensions evaluated, social, team, and change-management competencies are the strongest predictors of leadership effectiveness in telework environments, partially confirming the hypotheses based on theoretical and empirical literature.

Regarding the second research question (H2), Fisher’s Exact Test was employed, as the assumptions for the Chi-square test were not met. The choice for the Fisher’s Exact Test was made due to the distribution of responses across the contingency table, which included several cells with expected frequencies below 5. While the Chi-square test is commonly used for testing associations between categorical variables, it relies on the assumption that expected cell frequencies are sufficiently large (typically ≥ 5). Since this assumption is violated, Chi-square is not applicable and the validity of the results are compromised (

Field, 2013;

Agresti, 2002). In contrast, Fisher’s Exact Test does not rely on large-sample approximations and is particularly well-suited for small sample sizes or sparse data tables. Given the relatively small number of respondents in some categories of the “organizational investment in telework” variable, Fisher’s Exact Test was selected to ensure the robustness and reliability of the statistical inference. This approach enhances the methodological rigor of the analysis by providing an exact p-value, thereby avoiding the potential biases associated with asymptotic methods in small samples.

This test calculates the exact probability of obtaining the observed results (or more extreme outcomes) under the null hypothesis that there is no association between the variables. This probability is the p-value, and if it is less than or equal to the significance level (0.05), the null hypothesis is rejected, indicating a significant association.

H0. The variable “investment in telework” and e-leadership effectiveness are independent.

The value of significance obtained for the variable investment in telework was p = 0.288, which is above the 5% significance level. Therefore, the null hypothesis (H0) is not rejected, indicating no statistical evidence of an association between investment in telework and e-leadership effectiveness. Consequently, these variables are considered statistically independent within the context of this study.

5. Discussion

Out of the six formulated hypotheses, three—E-Social, E-Team, and E-Change—were statistically validated. These dimensions demonstrated significant associations with perceptions of e-leadership effectiveness, aligning with existing scientific literature that supports the SEC model.

The E-Social dimension showed the highest significance (

p < 0.001), indicating that e-leaders who build trust, adapt communication, and provide emotional support are key to effective e-leadership. This competency is particularly important for remote teams facing isolation and low motivation (

Van Wart et al., 2017;

Salin & Koponen, 2024). The findings suggest e-leaders fostering connection and empathy achieve better outcomes.

The E-Team dimension, associated with the e-leader’s ability to build and maintain cohesive and motivated teams, also showed a positive and significant relationship with e-leadership effectiveness (

p = 0.033). This finding supports

Van Wart et al.’s (

2017) view that e-leaders must foster a sense of belonging, strengthen each team member’s role, and ensure that teamwork is not lost due to physical distance. This challenge is widely recognized in the literature, as authors such as

Kempner (

2022) also highlight the importance of balancing group cohesion with individual autonomy. E-leadership effectiveness in this context depends on the leader’s ability to adapt traditional teamwork practices to digital tools and environments. As emphasized by

Wang et al. (

2023), effective leaders maintain consistent levels of interaction with their teams, alternating flexibly between face-to-face and digital methods, thus ensuring the continuity of team dynamics.

Kempner (

2022) reinforces that in digital environments, the challenge of balancing individual autonomy with group belonging requires leaders to demonstrate interpersonal sensitivity and skills.

The E-Change dimension also revealed statistical significance (

p = 0.006), indicating that the ability to manage change—whether technological, organizational, or procedural—positively contributes to e-leadership effectiveness. This result reinforces

Van Wart et al.’s (

2017) premise that e-leaders must be proactive in identifying improvements, planning transformations, and overseeing their effective implementation, especially in the constantly evolving digital environment. The rapid technological evolution and continuous digital innovations have challenged e-leaders to develop new ways of solving problems, requiring creativity, continuous learning, and the ability to implement innovative solutions (

Kempner, 2022).

In contrast, the E-Tech, E-Communication, and E-Trust dimensions were not statistically significant in the binary logistic regression model.

For E-Tech (

p = 0.054), the result was close to the threshold of statistical significance, suggesting a possible tendency, although insufficient to confirm the hypothesis. While the literature argues that e-leaders who use ICTs consistently demonstrate more effective e-leadership (

Wang et al., 2023) and emphasizes the importance of technological proficiency—including the selection and effective use of digital tools, troubleshooting, and supporting the team’s technological needs (

Van Wart et al., 2017)—this study indicates that, for the participants surveyed, such competence did not emerge as a determinant of e-leadership effectiveness. A possible explanation may lie in the fact that technological skills are now widely disseminated and expected of any professional, no longer standing out as differentiating factors between effective and less effective e-leaders. Nevertheless, given that the result is very close to the significance threshold, a larger sample could potentially yield a statistically significant result—possibly in a negative direction. This would mean that high levels of E-Tech competence do not necessarily lead to more effective e-leadership. Although seemingly counterintuitive, this finding aligns with literature suggesting that technological skills, while necessary, are not sufficient to guarantee effective leadership in virtual environments (

Van Wart et al., 2017).

The E-Communication dimension (

p = 0.138) was also not significant, even though the literature identifies clear, regular, and bidirectional communication as a pillar of e-leadership (

Van Wart et al., 2017). The literature notes that leaders use communication to ensure task completion and maintain positive relationships with their teams (

Salin & Koponen, 2024), and it highlights the relationship between communication skills and technological competence (

Wang et al., 2023). However, this result may indicate that perceptions of e-leadership effectiveness do not depend solely on communication quality but rather on how communication interacts with other competencies, such as social support, team motivation, or even how ICTs are used to communicate. Given the non-significant results for both E-Communication and E-Tech, this may also reflect digital communication saturation, where excessive or poorly directed communication reduces effectiveness.

Kempner (

2022) warns about the risks of unbalanced communication in digital contexts, while

Hafermalz (

2021) notes that e-leaders often attempt to compensate for physical absence through multiple messages—a strategy that may be perceived as micromanagement or generate communication “noise,” thereby undermining e-leadership effectiveness.

The non-significance of E-Trust dimension (

p = 0.287) competence is particularly noteworthy, given its centrality in the SEC model and its prominence in the literature (

Van Wart et al., 2017;

Wang et al., 2023). One plausible explanation is that trust in virtual environments may not operate as a direct, standalone predictor of leadership effectiveness. Instead, it may function as a mediating or moderating variable, influenced by other factors such as organizational culture, communication climate, or team norms. For instance, in organizations with strong cultures of transparency and psychological safety, trust may be embedded institutionally, reducing the need for leaders to actively cultivate it. Alternatively, trust may emerge as an outcome of other competencies—such as E-Social or E-Communication—rather than as an independent driver. This interpretation aligns with

Kempner’s (

2022) discussion where trust is shaped by broader organizational dynamics and not solely by individual leader behavior. Hence, although trust is theoretically relevant, the current model does not provide sufficient statistical evidence to confirm its direct influence on e-leadership effectiveness. In practical terms, demonstrating competencies such as E-Trust, E-Communication, and E-Tech does not necessarily imply that these have a measurable impact on e-leadership effectiveness.

The results indicate that effective e-leadership in teleworking environments is associated with competencies related to human relations, including establishing authentic connections (E-Social), fostering cohesive teams (E-Team), and leading change with agility (E-Change). The data also suggests that E-Tech competence supports other important skills, such as E-Communication and E-Trust, and this interdependence may explain their limited statistical significance.

Regarding the research question—whether there is an association between the effective e-leader profile and organizational preference for teleworking—Fisher’s Exact Test was applied, as previously noted. The significance value obtained (p = 0.288) indicates that, at a 5% significance level, there is no statistical evidence of a significant association between the variables analyzed. This suggests that, within the scope of this study, e-leadership effectiveness is not necessarily linked to organizational decisions to invest in teleworking as a preferred model.

Research indicates that adopting teleworking may signal a culture that values innovation, flexibility, and trust within organizations.

Eurofound and ILO (

2017) found telework linked to autonomy and organizational flexibility. However, this study’s data did not show statistically significant evidence for such a relationship. The findings reveal that, for some e-leaders, certain e-leadership competencies appear less pronounced, which aligns with literature indicating that leading remotely remains challenging. As noted by

Premuzic (

2025) and

Pinto (

2023), leaders trained in traditional, face-to-face contexts may face difficulties in supervising team performance, maintaining trust, and managing virtual collaboration.

A causal analysis of these findings suggests that while e-leaders can be effective, strategic decisions regarding work models are influenced by other factors—such as economic, cultural, legal, and sectoral ones—that extend beyond e-leadership competencies. Therefore, although this study does not confirm that increased investment in teleworking in Portugal is directly related to e-leadership effectiveness, existing literature indicates that teleworking has been on the rise in recent years (

Redação, 2025;

Expresso, 2025). This trend may be associated with other factors deserving future research attention, given that teleworking is linked to numerous benefits such as reduced stress, greater work-life balance, increased productivity, shorter commuting times, reduced social contact, and higher control over work patterns (

Delfino & van der Kolk, 2021).

Consistent with this theoretical position, the empirical results of this study show that 81.2% of e-leaders reported a significant increase in teleworking practices within their organizations, as shown in

Table 11.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

The present study contributes to the literature on e-leadership by empirically applying the SEC model (

Van Wart et al., 2017) to the Portuguese organizational context, with a specific focus on its relationship to telework adoption. By doing so, it offers new insights into how e-leadership competencies manifest in a national setting that has shown a distinct trajectory in embracing remote work.

The findings partially validate the SEC model. Among the six core competencies, E-Social, E-Team, and E-Change were significantly associated with perceived e-leadership effectiveness. These results reinforce the importance of interpersonal, team building, and change management skills in virtual leadership contexts. Conversely, E-Communication, E-Tech, and E-Trust did not show statistically significant associations, suggesting that these competencies may either be baseline expectations in digital environments or operate through indirect mechanisms not captured in the current model.

Importantly, the study found no statistically significant association between e-leadership effectiveness and organizational investment in telework. This indicates that while individual leadership competencies are crucial for managing remote teams, strategic decisions about telework adoption may be influenced more by structural, cultural, or sector-specific factors.

Theoretically, this research supports the adaptability of the SEC model beyond its original context, while also highlighting the need to reconsider the relative weight and interaction of its dimensions. The Portuguese case suggests that some competencies may be more context-sensitive or mediated by organizational culture and digital maturity.

Practically, the validated instrument provides a useful diagnostic tool for assessing and developing e-leadership capabilities. Organizations can leverage these insights to design targeted training programs that prioritize the most impactful competencies for remote leadership success.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

Despite its contributions, this study also presents certain limitations, accompanied by suggestions for future research. Although the use of questionnaires is widely accepted in empirical and theoretical research (

Fachin, 2005;

Hair et al., 2005), some limitations are inherent to this method. Given that the questionnaire was administered online, it was not possible to control the conditions under which respondents completed it, which may affect the consistency and reliability of responses. Additionally, subjective interpretation of the questions could have introduced response variability. Furthermore, since this research was conducted within a defined time frame, it does not allow for longitudinal verification of changes that may have occurred after data collection and analysis.

Another limitation concerns the composition of the sample, which consisted predominantly of e-leaders from large organizations (with more than 250 employees), particularly within the technology, communication, and services sectors. This concentration may limit the generalizability of findings to other organizational contexts. Given that e-leadership has been shown to influence organizational competitiveness and digital effectiveness (

Hüsing et al., 2013), future studies should apply the SEC model to micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises, as well as to other industries, to better understand how e-competencies manifest and evolve across diverse settings. The SEC framework and the questionnaire developed here can serve as diagnostic and evaluative tools for such future inquiries.

A second limitation lies in the relatively short period during which the survey was active, which, while sufficient for the study’s objectives, resulted in a limited number of responses. Future studies are encouraged to apply the same instrument over extended periods and through broader dissemination strategies, enabling larger and more representative samples. Expanding the sample size would allow for more robust analyses and enhance the validity and generalizability of findings, thereby contributing to the consolidation of e-leadership as a field of scientific study.

Finally, a third limitation pertains to the scope of the SEC model itself. In its original formulation, the model identifies six core competencies but does so in a relatively broad manner, focusing primarily on soft skills. Consequently, the questionnaire items reflect this emphasis, potentially overlooking more specific or technical aspects. Future research could expand upon the SEC model by incorporating additional dimensions or refining existing ones, particularly by integrating hard-skill components. For instance, within the e-tech dimension, future studies could assess proficiency in specific digital tools such as Excel, Power BI, project management software, or collaborative platforms, allowing for a more granular and market-aligned understanding of digital leadership capabilities.

Future research should explore the potential indirect effects by employing structural equation modelling (SEM) or mediation analysis to test whether E-Trust influences leadership effectiveness through its interaction with other competencies or contextual variables such as organizational culture. Additionally, qualitative studies could provide deeper insight into how trust is perceived and built in remote leadership contexts, particularly in cultures with high power distance or collectivist orientations, such as Portugal.