Gossip Gone Toxic: The Dual Role of Self-Esteem and Emotional Contagion in Counterproductive Workplace Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

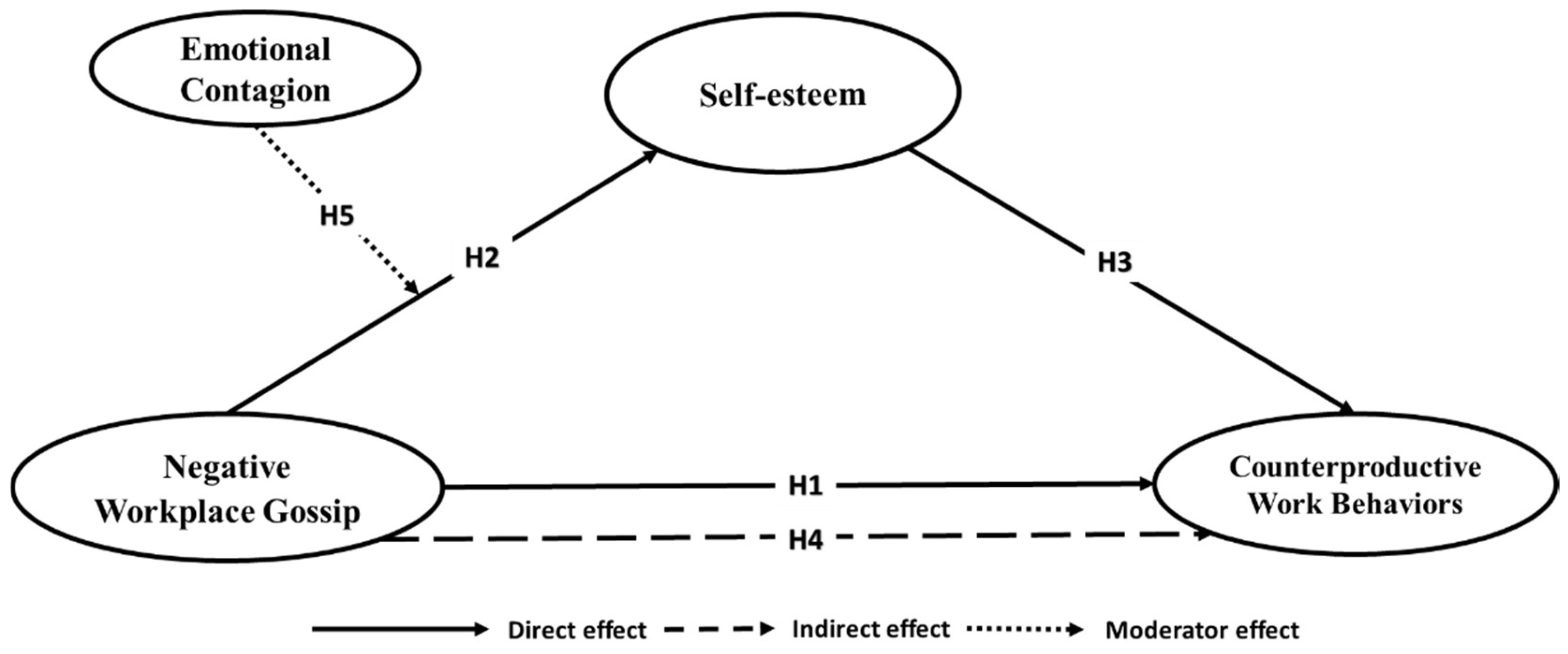

2. Underpinned Theory and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory

2.2. The Interplay Among NWG, Self-Esteem, and CWB

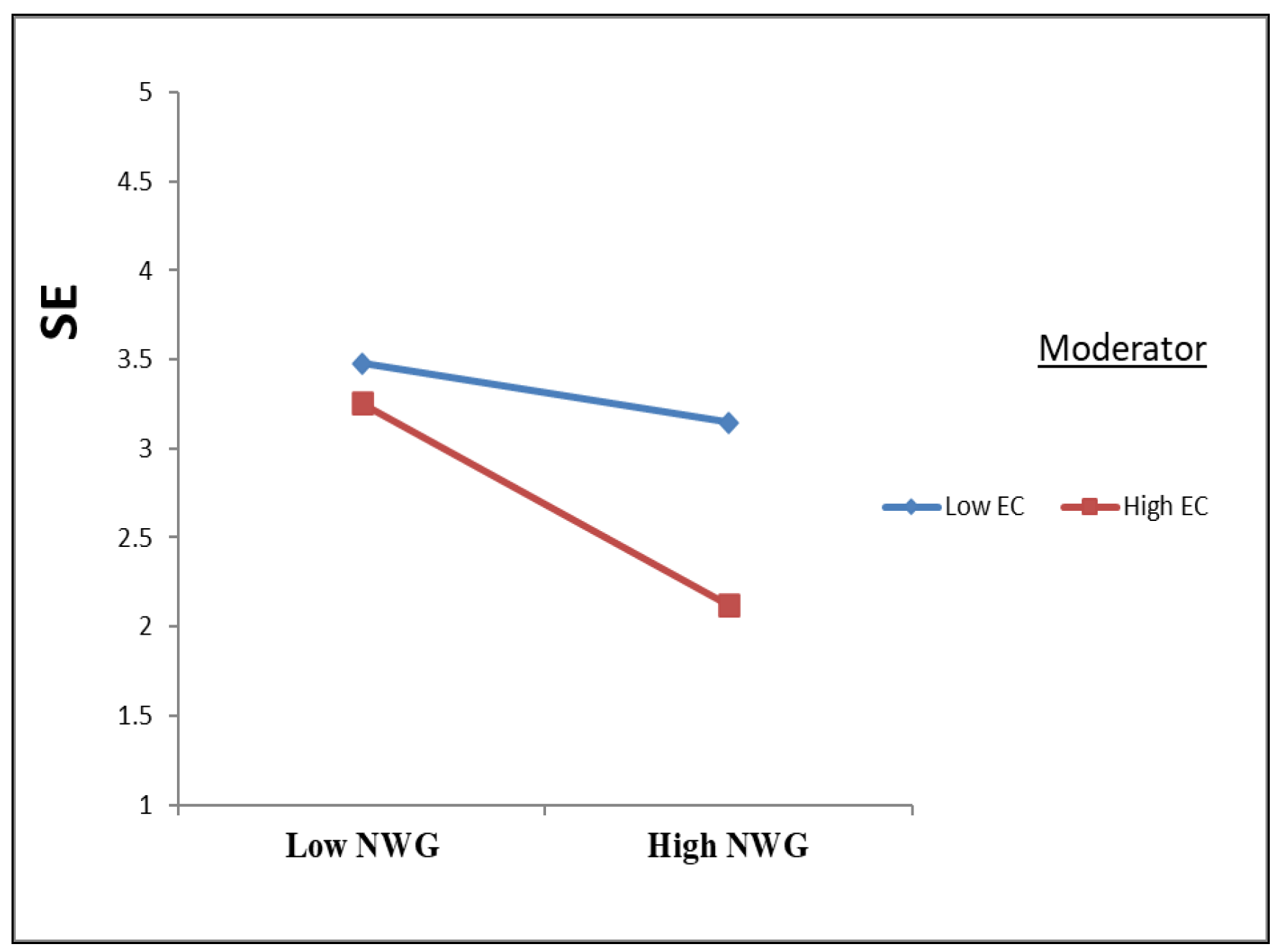

2.3. The Moderating Effect of Emotional Contagion

3. Methods

3.1. Measures

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Test of Common Method Bias (CMB) and Normality

4.2. The Measurement Model

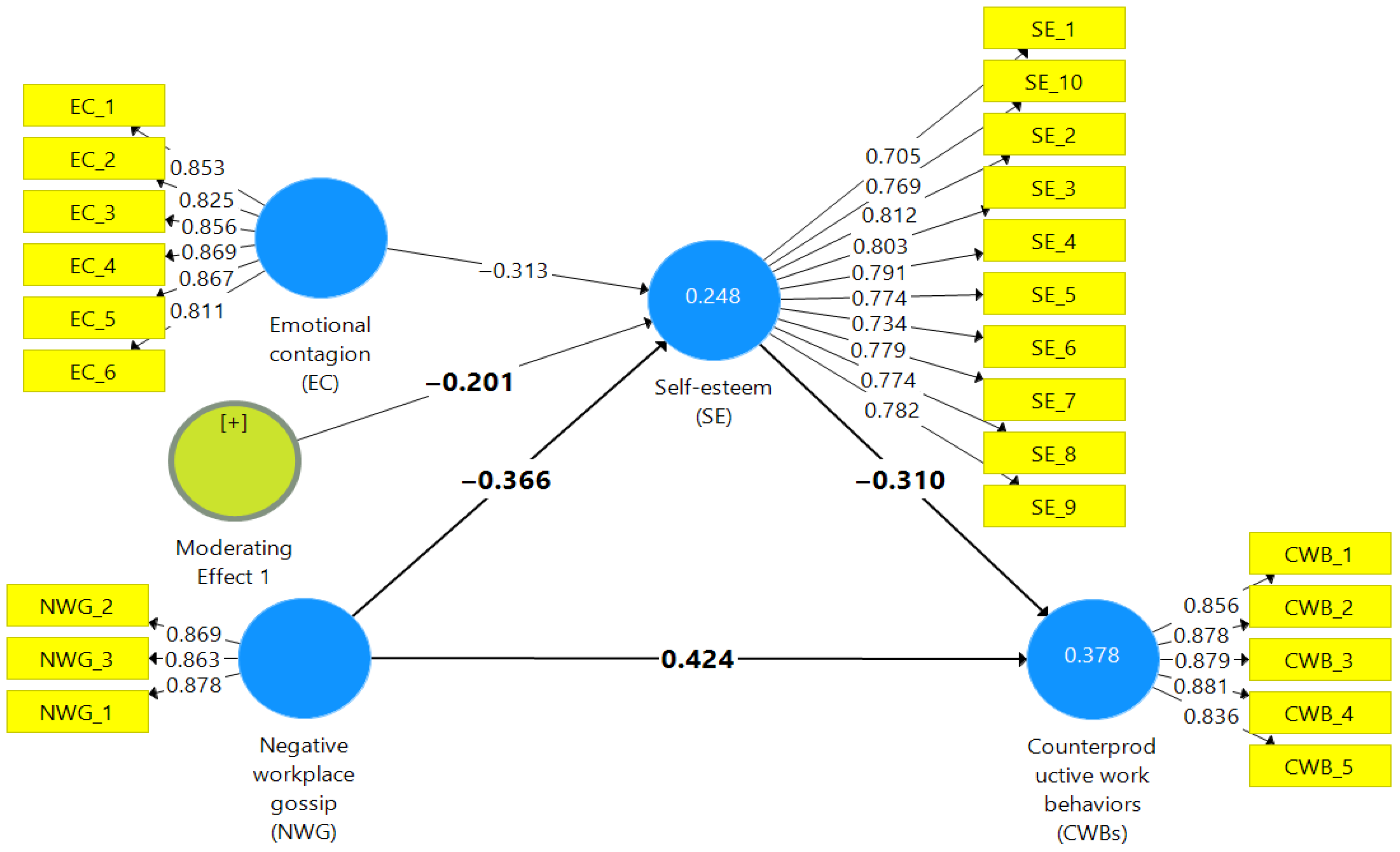

4.3. Structural Model Estimation and Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications and Suggestions

6. Study Limitations and Future Research

7. Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdulaziz, T. A., Mansour, M. A., Elwardany, W. M. M., & Fayyad, S. (2025). The mediating role of psychological detachment between work overload and workplace withdrawal. Current Psychology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulghani, A. H., Almelhem, M., Basmaih, G., Alhumud, A., Alotaibi, R., Wali, A., & Abdulghani, H. M. (2020). Does self-esteem lead to high achievement of the science college’s students? A study from the six health science colleges. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences, 27(2), 636–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboutaleb, M., Mohammad, A., & Fayyad, S. (2025). Emotional contagion in hotels: How psychological resilience shapes employees’ performance, satisfaction, and retention. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, U. A., Singh, S. K., & Cooke, F. L. (2023). Does co-worker incivility increase perceived knowledge hiding? The mediating role of work engagement and turnover intentions and the moderating role of cynicism. British Journal of Management, 35(3), 1281–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajay, B., & Sedari Mudiyanselage, A. (2025). Gossip in a group’s life: Gossip functions during different stages of group development. Organizational Psychology Review, 15(3), 291–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgunduz, Y., Sanli Kayran, S. C., & Metin, U. (2023). The background of restaurant employees’ revenge intention: Supervisor incivility, organizational gossip, and blaming others. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 36(6), 1816–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqhaiwi, Z. O., Djurkovic, N., Luu, T., & Gunasekara, A. (2024). The self-regulatory role of trait mindfulness in workplace bullying, hostility and counterproductive work behaviours among hotel employees. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 122, 103843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsawy, O., Khalil, R., Fayyad, S., & Emam, A. M. (2024). The impact of employees’ training perceptions on turnover intention in tourism and hospitality industries: A mediation moderation model. The International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Studies, 7(2), 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampofo, E. T., & Karatepe, O. M. (2025). How concerned are bystanders? Consequences of vicarious abusive supervision: Parallel and sequential multiple mediating impacts and resilience as a moderator. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 125, 104004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun Kumar, P., & Vilvanathan, L. (2024). When talk matters: The role of negative supervisor gossip and employee agreeableness in feedback seeking and job performance. Management Research Review, 47(10), 1501–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babalola, M. T., Ren, S., Kobinah, T., Qu, Y. E., Garba, O. A., & Guo, L. (2019). Negative workplace gossip: Its impact on customer service performance and moderating roles of trait mindfulness and forgiveness. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 80, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardoel, E. A., & Drago, R. (2021). Acceptance and strategic resilience: An application of conservation of resources theory. Group & Organization Management, 46(4), 657–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, A. E., Milosevic, I., & DeArmond, S. (2023). Firm stress, adaptive responses, and unpredictable, resource-depleting external shocks: Leveraging conservation of resources theory and dynamic capabilities (pp. 1–16). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written material. In H. C. Triandis, & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology: Methodology, allyn and bacon (pp. 389–444). Scientific Research Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, G., & Robinson, S. L. (2009, August 7–11). They’re talking about me again: The impact of being the target of gossip on emotional distress and withdrawal. Academy of Management Conference, Chicago, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L., & Zhang, S. (2025). Employees’ unethical pro-organizational behavior and subsequent internal whistle-blowing. Chinese Management Studies, 19(1), 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B., Peng, Y., Tian, J., & Shaalan, A. (2024). How negative workplace gossip undermines employees’ career growth: From a reputational perspective. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 36(7), 2443–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, P. J., West, S. G., & Finch, J. F. (1996). The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 1(1), 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, D., Kundi, Y. M., Sardar, S., & Shahid, S. (2021). Perceived organizational injustice and counterproductive work behaviours: Mediated by organizational identification, moderated by discretionary human resource practices. Personnel Review, 50(7/8), 1545–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delcea, C., Rad, D., Toderici, O. F., & Bululoi, A. S. (2023). Posttraumatic growth, maladaptive cognitive schemas and psychological distress in individuals involved in road traffic accidents—A conservation of resources theory perspective. Healthcare, 11(22), 2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elshaer, I. A., Azazz, A. M. S., Alyahya, M., Mohammad, A. A. A., Fayyad, S., & Elsawy, O. (2025a). Emotional contagion in the hospitality industry: Unraveling its impacts and mitigation strategies through a moderated mediated PLS-SEM approach. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(1), 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I. A., Azazz, A. M. S., Fayyad, S., & Elsawy, O. (2025b). Navigating workplace toxicity: The relationship between abusive supervision and helping behavior among hotel employees with self-esteem and emotional contagion as buffers. Administrative Sciences, 15(8), 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z., & Dawson, P. (2022). Gossip as evaluative sensemaking and the concealment of confidential gossip in the everyday life of organizations. Management Learning, 53(2), 146–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest, A. L., Sigler, K. N., Bain, K. S., O’Brien, E. R., & Wood, J. V. (2023). Self-esteem’s impacts on intimacy-building: Pathways through self-disclosure and responsiveness. Current Opinion in Psychology, 52, 101596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, F. (2024). Time-lagged effects of student misbehavior on teacher counterproductive work behaviors: The role of negative affect and regulatory focus. Psychology in the Schools, 61(7), 2845–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, A. H., Malhotra, A., & Segars, A. H. (2001). Knowledge management: An organizational capabilities perspective. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T., Park, J., & Hyun, H. (2020). Customer response toward employees’ emotional labor in service industry settings. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 52, 101899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, M. K. (2024). Into the unknown: Anticipatory stressors in the stress process paradigm. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, G., Gong, Q., Li, S., & Liang, X. (2021). Don’t speak ill of others behind their backs: Receivers’ ostracism (sender-oriented) reactions to negative workplace gossip. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Haldorai, K., Kim, W. G., & Phetvaroon, K. (2022). Beyond the bend: The curvilinear effect of challenge stressors on work attitudes and behaviors. Tourism Management, 90, 104482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, F., Shaheen, S., & Younas, A. (2025). What drives ostracised knowledge hiding? Negative work place gossips and neuroticism perspective. VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems, 55(5), 1304–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung, F.-M., Krohn, C., & Pirschtat, M. (2019). Better than its reputation? Gossip and the reasons why we and individuals with “dark” personalities talk about others. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, C., Sommerfield, A., & von Ungern-Sternberg, B. S. (2020). Resilience strategies to manage psychological distress among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A narrative review. Anaesthesia, 75(10), 1364–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, J., Putnick, D. L., & Bornstein, M. H. (2017). II. More than just convenient: The scientific merits of homogeneous convenience samples. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 82(2), 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahanzeb, S., Fatima, T., & De Clercq, D. (2021). When workplace bullying spreads workplace deviance through anger and neuroticism. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 29(4), 1074–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelić, M. (2022). How do we process feedback? The role of self-esteem in processing self-related and other-related information. Acta Psychologica, 227, 103592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L., Lawrence, A., & Xu, X. (2022). Does a stick work? A meta-analytic examination of curvilinear relationships between job insecurity and employee workplace behaviors. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 43(8), 1410–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junça Silva, A., & Martins, S. (2023). Measuring counterproductive work behavior in telework settings: Development and validation of the counterproductive [tele]work behavior scale (CTwBS). International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 33(5), 928–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H. S., & Yoon, H. H. (2012). The effects of emotional intelligence on counterproductive work behaviors and organizational citizen behaviors among food and beverage employees in a deluxe hotel. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(2), 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairy, H. A., Fayyad, S., & El Sawy, O. (2025). AI awareness and work withdrawal in hotel enterprises: Unpacking the roles of psychological contract breach, job crafting, and resilience. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, J., Weng, Q. D., Ghani, U., Usman, M., Asim, M., & Batool, M. (2025). Supervisor negative gossip and target’s helping behavior: The role of emotional exhaustion and Islamic work ethics. Baltic Journal of Management, 20(4), 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A., & Chaudhary, R. (2023). Perceived organizational politics and workplace gossip: The moderating role of compassion. International Journal of Conflict Management, 34(2), 392–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A. G., Li, Y., Akram, Z., & Akram, U. (2022). Does bad gossiping trigger for targets to hide knowledge in morally disengaged? New multi-level insights of team relational conflict. Journal of Knowledge Management, 26(9), 2370–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A. G., Li, Y., Akram, Z., & Akram, U. (2023). Why and how targets’ negative workplace gossip exhort knowledge hiding? Shedding light on organizational justice. Journal of Knowledge Management, 27(5), 1458–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. A., Selem, K. M., Zubair, S. S., & Shoukat, M. H. (2025). Linking coworker friendship with incivility: Comparison between headwaiters and servers in family-style restaurants. Kybernetes, 54(2), 705–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejcie, R. V., & Morgan, D. W. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30(3), 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, A., Soumyaja, D., & Joseph, J. (2024). Workplace bullying and employee silence: The role of affect-based trust and climate for conflict management. International Journal of Conflict Management, 35(5), 1034–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. B., Liu, S. H., & Maertz, C. (2022). The relative impact of employees’ discrete emotions on employees’ negative word-of-mouth (NWOM) and counterproductive workplace behavior (CWB). Journal of Product & Brand Management, 31(7), 1018–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Canziani, B. F., & Barbieri, C. (2018). Emotional labor in hospitality: Positive affective displays in service encounters. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 18(2), 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L. H., Nishioka, M., Evans, R., Brown, D. J., Shen, W., & Lian, H. (2022). Unbalanced, unfair, unhappy, or unable? Theoretical integration of multiple processes underlying the leader mistreatment-employee CWB relationship with meta-analytic methods. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 29(1), 33–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M., Liu, X., Muskat, B., Leung, X. Y., & Liu, S. (2024). Employees’ self-esteem in psychological contract: Workplace ostracism and counterproductive behavior. Tourism Review, 79(1), 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Lu, W., Liu, S., & Qin, C. (2023). Hatred out of love or love can be all-inclusive? Moderating effects of employee status and organizational affective commitment on the relationship between turnover intention and CWB. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 993169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D., & Hong, D. (2022). Emotional contagion: Research on the influencing factors of social media users’ negative emotional communication during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 931835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinescu, E. (2024). When do gossip receivers assess negative gossip as justifiable? A goal framing approach. Acta Psychologica, 247, 104327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrabian, A., & Epstein, N. (1972). A measure of emotional empathy. Journal of Personality, 40(4), 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oggiano, M. (2022). Neurophysiology of emotions. In Neurophysiology—Networks, plasticity, pathophysiology and behavior. IntechOpen. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar Ahmed, M. A., & Zhang, J. (2025). The effect of managers’ bottom-line attitude on counterproductive work behavior: The mediation of organizational cynicism and moderation of ethical individuality. Current Psychology, 44(3), 1717–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, U., & Robins, R. W. (2022). Is high self-esteem beneficial? Revisiting a classic question. American Psychologist, 77(1), 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petitta, L., Jiang, L., & Härtel, C. E. J. (2017). Emotional contagion and burnout among nurses and doctors: Do joy and anger from different sources of stakeholders matter? Stress and Health, 33(4), 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochazkova, E., & Kret, M. E. (2017). Connecting minds and sharing emotions through mimicry: A neurocognitive model of emotional contagion. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 80, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, S., Zhang, X., & Liu, J. (2024). Impacts of work-related rumination on employee’s innovative performance: Based on the conservation of resources theory. Baltic Journal of Management, 19(4), 435–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rink, L. C., Silva, S. G., Adair, K. C., Oyesanya, T. O., Humphreys, J. C., & Sexton, J. B. (2023). Characterizing burnout and resilience among nurses: A latent profile analysis of emotional exhaustion, emotional thriving and emotional recovery. Nursing Open, 10(11), 7279–7291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosalina, K., & Jusoh, R. (2024). Levers of control, counterproductive work behavior, and work performance: Evidence from indonesian higher education institutions. Sage Open, 14(3), 21582440241278455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt183pjjh (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Rouxel, G., Michinov, E., & Dodeler, V. (2016). The influence of work characteristics, emotional display rules and affectivity on burnout and job satisfaction: A survey among geriatric care workers. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 62, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabir, M. R., Majid, M. B., Aslam, M. Z., Rehman, A., & Rehman, S. (2024). Understanding the linkage between abusive supervision and counterproductive work behavior: The role played by resilience and psychological contract breach. Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), 2323794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, S., Lodhi, R. N., Jain, V., & Sharma, P. (2022). A dark side of land revenue management and counterproductive work behavior: Does organizational injustice add fuel to fire? Journal of Public Procurement, 22(4), 265–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y., & Lei, X. (2022). Exploring the impact of leadership characteristics on subordinates’ counterproductive work behavior: From the organizational cultural psychology perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 818509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X., & Guo, S. (2022). The impact of negative workplace gossip on employees’ organizational self-esteem in a differential atmosphere. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 854520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syahrivar, J., Hermawan, S. A., Gyulavári, T., & Chairy, C. (2022). Religious compensatory consumption in the Islamic context: The mediating roles of religious social control and religious guilt. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 34(4), 739–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M. A., Da, G., Javed, M., Akhtar, M. W., & Wang, X. (2024). Employees’ foe or friend: Artificial intelligence and employee outcomes. The Service Industries Journal, 45(11–12), 1100–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, E., & Coughlan, J. (2023). Burnout and counterproductive workplace behaviours among frontline hospitality employees: The effect of perceived contract precarity. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 35(2), 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Xia, B., & Bi, W. (2025). Keeping silent or playing good citizen? Differential mechanisms of negative workplace gossip on targets reactions. Personnel Review, 54(1), 150–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C. E., Thomas, J. S., Bennett, A. A., Banks, G. C., Toth, A., Dunn, A. M., McBride, A., & Gooty, J. (2024). The role of discrete emotions in job satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 45(1), 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.-Z., Birtch, T. A., Chiang, F. F. T., & Zhang, H. (2018). Perceptions of negative workplace gossip: A self-consistency theory framework. Journal of Management, 44(5), 1873–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xerri, M. J., Cozens, R., & Brunetto, Y. (2023). Catching emotions: The moderating role of emotional contagion between leader-member exchange, psychological capital and employee well-being. Personnel Review, 52(7), 1823–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z., Luo, J., & Zhang, X. (2020). Gossip is a fearful thing: The impact of negative workplace gossip on knowledge hiding. Journal of Knowledge Management, 24(7), 1755–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zablah, A. R., Sirianni, N. J., Korschun, D., Gremler, D. D., & Beatty, S. E. (2017). Emotional convergence in service relationships: The shared frontline experience of customers and employees. Journal of Service Research, 20(1), 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., & Zheng, J. (2024). Unraveling the role of external social support in coping with negative workplace gossip. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 52(3), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H., Ma, Y., & Chen, Y. (2024). The double-edged sword of negative workplace gossip: When and how negative workplace gossip promotes versus inhibits knowledge hiding. Current Psychology, 43(25), 21840–21856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, A., Liu, Y., Su, X., & Xu, H. (2019). Gossip fiercer than a tiger: Effect of workplace negative gossip on targeted employees’ innovative behavior. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 47(5), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X., Chen, X., Chen, F., Luo, C., & Liu, H. (2020). The influence of negative workplace gossip on knowledge sharing: Insight from the cognitive dissonance perspective. Sustainability, 12(8), 3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors and Items | λ | VIF | Mean | SD | SK | KU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative workplace gossip (NWG) (α = 0.840, CR = 0.903, AVE = 0.757) | ||||||

| NWG_1 | 0.878 | 1.955 | 3.856 | 1.113 | −0.846 | −0.095 |

| NWG_2 | 0.869 | 1.965 | 3.847 | 1.144 | −0.841 | −0.159 |

| NWG_3 | 0.863 | 2.029 | 3.753 | 1.120 | −0.789 | −0.147 |

| Self-esteem (SE) (α = 0.925, CR = 0.937, AVE = 0.597) | ||||||

| SE_1 | 0.705 | 2.636 | 3.158 | 1.060 | 0.238 | −0.787 |

| SE_2 | 0.812 | 3.462 | 3.293 | 1.030 | 0.212 | −0.771 |

| SE_3 | 0.803 | 2.891 | 3.302 | 1.014 | 0.070 | −0.545 |

| SE_4 | 0.791 | 3.186 | 3.259 | 1.100 | 0.315 | −0.851 |

| SE_5 | 0.774 | 3.209 | 3.368 | 1.159 | −0.033 | −0.994 |

| SE_6 | 0.734 | 2.776 | 3.259 | 1.042 | 0.175 | −0.835 |

| SE_7 | 0.779 | 2.849 | 3.281 | 0.987 | 0.175 | −0.683 |

| SE_8 | 0.774 | 2.623 | 3.318 | 0.944 | 0.098 | −0.381 |

| SE_9 | 0.782 | 3.043 | 3.300 | 1.055 | 0.248 | −0.750 |

| SE_10 | 0.769 | 3.031 | 3.350 | 1.143 | −0.049 | −0.891 |

| Counterproductive work behavior (CWB) (α = 0.917, CR = 0.937, AVE = 0.750) | ||||||

| CWB_1 | 0.856 | 2.658 | 2.979 | 1.354 | −0.225 | −1.211 |

| CWB_2 | 0.878 | 3.142 | 3.076 | 1.353 | −0.277 | −1.182 |

| CWB_3 | 0.879 | 2.836 | 3.101 | 1.427 | −0.169 | −1.304 |

| CWB_4 | 0.881 | 3.079 | 3.178 | 1.472 | −0.220 | −1.331 |

| CWB_5 | 0.836 | 2.544 | 3.199 | 1.278 | −0.417 | −0.804 |

| Emotional contagion (EC) (α = 0.921, CR = 0.938, AVE = 0.718) | ||||||

| EC_1 | 0.853 | 2.744 | 3.698 | 1.181 | −0.689 | −0.520 |

| EC_2 | 0.825 | 2.275 | 3.703 | 1.200 | −0.660 | −0.643 |

| EC_3 | 0.856 | 2.525 | 3.767 | 1.341 | −0.611 | −1.070 |

| EC_4 | 0.869 | 2.898 | 3.645 | 1.159 | −0.698 | −0.485 |

| EC_5 | 0.867 | 2.764 | 3.769 | 1.236 | −0.762 | −0.597 |

| EC_6 | 0.811 | 2.261 | 3.705 | 1.268 | −0.768 | −0.614 |

| Fornell–Larcker Criterion | HTMT Matrix | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Counterproductive work behavior | 0.866 | |||||||

| Emotional Contagion | 0.177 | 0.847 | 0.188 | |||||

| Negative workplace gossip | 0.544 | 0.463 | 0.870 | 0.617 | 0.527 | |||

| Self-esteem | −0.474 | −0.402 | −0.387 | 0.773 | 0.510 | 0.412 | 0.423 | |

| Hypothesis | β | t | p | Remark | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | ||||||

| H1: NWG -> CWB | 0.424 | 9.902 | 0.000 | ✔ | ||

| H2: NWG -> SE | −0.366 | 6.500 | 0.000 | ✔ | ||

| H3: SE -> CWB | −0.310 | 6.901 | 0.000 | ✔ | ||

| Indirect mediating effect | ||||||

| H4: NWG -> SE -> CWB | 0.113 | 4.405 | 0.000 | ✔ | ||

| Moderating effect | ||||||

| H5: NWG × EC -> SE | −0.201 | 4.758 | 0.000 | ✔ | ||

| Counterproductive work behavior | R2 | 0.378 | Q2 | 0.265 | ||

| Self-esteem | R2 | 0.248 | Q2 | 0.130 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdelghani, A.A.A.; Ahmed, H.A.M.; Zamil, A.M.A.; Elsawy, O.; Fayyad, S.; Elshaer, I.A. Gossip Gone Toxic: The Dual Role of Self-Esteem and Emotional Contagion in Counterproductive Workplace Behavior. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 359. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090359

Abdelghani AAA, Ahmed HAM, Zamil AMA, Elsawy O, Fayyad S, Elshaer IA. Gossip Gone Toxic: The Dual Role of Self-Esteem and Emotional Contagion in Counterproductive Workplace Behavior. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(9):359. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090359

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdelghani, Abdelrahman A. A., Hebatallah A. M. Ahmed, Ahmad M. A. Zamil, Osman Elsawy, Sameh Fayyad, and Ibrahim A. Elshaer. 2025. "Gossip Gone Toxic: The Dual Role of Self-Esteem and Emotional Contagion in Counterproductive Workplace Behavior" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 9: 359. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090359

APA StyleAbdelghani, A. A. A., Ahmed, H. A. M., Zamil, A. M. A., Elsawy, O., Fayyad, S., & Elshaer, I. A. (2025). Gossip Gone Toxic: The Dual Role of Self-Esteem and Emotional Contagion in Counterproductive Workplace Behavior. Administrative Sciences, 15(9), 359. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090359