Leadership, Knowledge Management, and Transactive Memory System in International Technical Assistance: Policy Insights for Entrepreneurial Resilience in Emerging Markets

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- RQ1: How do knowledge management (KM) mechanisms operate within technical assistance interventions targeting export development in emerging economies?

- -

- RQ2: What role do transactive memory systems (TMS) play in facilitating or hindering knowledge transfer between international consultants and local stakeholders?

- -

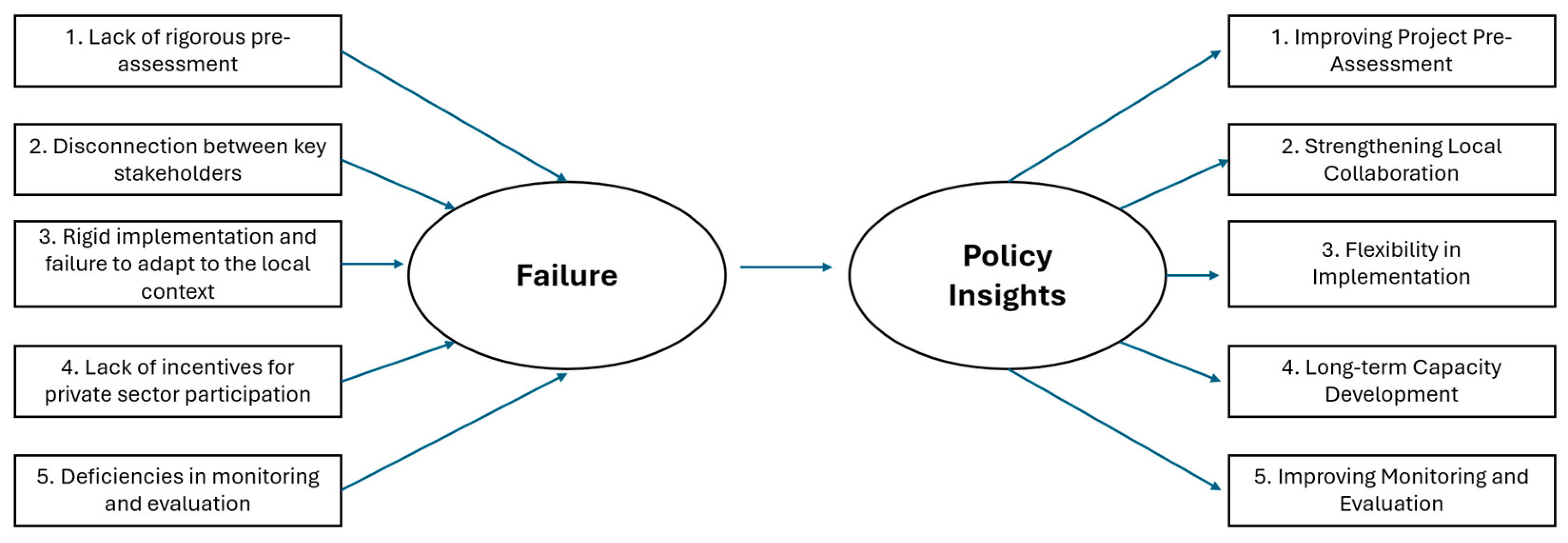

- RQ3: What factors explain the failure of TA interventions to build sustainable entrepreneurial resilience, and what policy insights can be derived from such failures?

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Literature on Technical Assistance (TA)

2.2. Knowledge Management and Transactive Memory Systems in Technical Assistance

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Methodological Approach and Justification

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Case Study: Export Consortia in Lesotho

4.1. AfDB and Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs)

4.2. The Economic Diversification Support Project (EDSP)

4.2.1. Phase 1

4.2.2. Phase 2

4.2.3. Phase 3

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical and Policy Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Semi-Structured Interview Guide

- Section 1: Background and Role Understanding

- Section 2: Knowledge Management Processes (RQ1)

- Section 3: Transactive Memory Systems and Coordination (RQ2)

- Section 4: Barriers and Challenges (RQ3)

- Section 5: Sustainability and Learning

- Closing

References

- Addison, T., Sen, K., & Tarp, F. (2020). COVID-19: Macroeconomic dimensions in the developing world (No. 2020/74). WIDER Working Paper. The United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- African Development Bank (AfDB). (2025). Available online: https://www.afdb.org/en (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Alshebami, A. S. (2025). Purpose-driven resilience: A blueprint for sustainable growth in micro-and small enterprises in turbulent contexts. Sustainability, 17(5), 2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argote, L., & Miron-Spektor, E. (2011). Organizational learning: From experience to knowledge. Organization Science, 22(5), 1123–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariño, A., & de la Torre, J. (1998). Learning from failure: Towards an evolutionary model of collaborative ventures. Organization Science, 9(3), 306–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babb, S. L., & Carruthers, B. G. (2008). Conditionality: Forms, function, and history. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 4(1), 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balassa, B. (1965). Trade liberalisation and ‘revealed’ comparative advantage. The Manchester School, 33(2), 99–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, S., Cohen, A., & Meckstroth, A. (2018). Providing TA to local programs and communities: Lessons from a scan of initiatives offering TA to human services programs. US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation.

- Bazbauers, A. R. (2020). World Bank technical assistance: Participation, policy movement, and sympathetic interlocutors. Policy Studies, 41(6), 567–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebek, U. G. (2011). Consistency of the proposed additive measures of revealed comparative advantage. Economics Bulletin, 31(3), 2491–2499. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, E. J. (1993). Rethinking technical cooperation: Reforms for capacity building in Africa. United Nations Development Programme. [Google Scholar]

- Birdsall, N. (2018). The dilemma of the African development bank: Does governance matter for the long-run financing of the MDBs? (Vol. 498) Center for Global Development. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandon, D. P., & Hollingshead, A. B. (2004). Transactive memory systems in organizations: Matching tasks, expertise, and people. Organization Science, 15(6), 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, S. (2014). 14 unstructured and semi-structured interviewing. In The Oxford handbook of qualitative research (p. 277). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Broome, A., & Seabrooke, L. (2015). Shaping policy curves: Cognitive authority in transnational capacity building. Public Administration, 93(4), 956–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broome, A., & Seabrooke, L. (2020). Recursive recognition in the international political economy. Review of International Political Economy, 28(2), 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Chilenski, S. M., Perkins, D. F., Olson, J., Hoffman, L., Feinberg, M. E., Greenberg, M., Welsh, J., Crowley, D. M., & Spoth, R. (2016). The power of a collaborative relationship between technical assistance providers and community prevention teams: A correlational and longitudinal study. Evaluation and Program Planning, 54, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devadas, D., Theriault, A., McGahan, A. M., & Govani, S. (2021). White paper series: Technical assistance support for health innovations in low and middle-income countries. Gates Open Research, 5(28), 28. [Google Scholar]

- DeWalt, K. M., & DeWalt, B. R. (2011). Participant observation: A guide for fieldworkers (2nd ed.). AltaMira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dreher, A., Lang, V. F., & Richert, K. (2019). The political economy of International Finance Corporation lending. Journal of Development Economics, 140, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunst, C. J., Annas, K., Wilkie, H., & Hamby, D. W. (2019). Scoping review of the core elements of technical assistance models and frameworks. World Journal of Education, 9(2), 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterly, W. (2006). Reliving the 1950s: The big push, poverty traps, and takeoffs in economic development. Journal of Economic Growth, 11, 289–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, R. M., Fretz, R. I., & Shaw, L. L. (2011). Writing ethnographic fieldnotes. University of Chicago press. [Google Scholar]

- Endri, E., Fatmawatie, N., Sugianto, S., Humairoh, H., Annas, M., & Wiwaha, A. (2022). Determinants of efficiency of Indonesian Islamic rural banks. Decision Science Letters, 11(4), 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engen, L., & Prizzon, A. (2018). A guide to multilateral development banks. Overseas Development Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. (2017). Mantras and myths: The disenchantment of mixed-methods research and revisiting triangulation as a perspective. Qualitative Inquiry, 23(1), 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiadou, E., Steinmo, M. T., & Lauvås, T. (2024). Development of transactive memory systems in new venture teams. International Small Business Journal, 42(1), 124–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerring, J. (2004). What is a case study and what is it good for? American Political Science Review, 98(2), 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, S. C. (2012). Making performance measurement systems more effective in public sector organizations. Measuring Business Excellence, 16(1), 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R. M. (1996). Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17(S2), 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith-Jones, S. (2016). Development banks and their key roles: Supporting investment, structural transformation and sustainable development. Brot für die Welt. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A. K., & Govindarajan, V. (2000). Knowledge flows within multinational corporations. Strategic Management Journal, 21(4), 473–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjern, B., & Porter, D. O. (1981). Implementation structures: A new unit of administration. Organization Studies, 2(3), 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekman, B., & Nicita, A. (2011). Trade policy, trade costs, and developing country trade. World Development, 39(12), 2069–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, C. (2014). The politics of loan pricing in multilateral development banks. Review of International Political Economy, 21(3), 611–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, C. (2016). The “invisible hand”: Financial pressures and organizational convergence in multilateral development banks. The Journal of Development Studies, 52(1), 92–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, C., & Michaelowa, K. (2013). Shopping for development: Multilateral lending, shareholder composition and borrower preferences. World Development, 44, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inkpen, A. C., & Tsang, E. W. K. (2005). Social capital, networks, and knowledge transfer. Academy of Management Review, 30(1), 146–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, D. L. (2020). Principles, approaches and issues in participant observation. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kaboré, A. (2022). Historical analysis of bilateral and multilateral cooperation agencies’ interventions in education and training in Burkina Faso from 1960 to 2015. International Journal of Education, Culture and Society, 7(4), 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallio, H., Pietilä, A. M., Johnson, M., & Kangasniemi, M. (2016). Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(12), 2954–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, J., & Wandersman, A. (2016). Technical assistance to enhance prevention capacity: A research synthesis of the evidence base. Prevention Science, 17, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, I. (2020). Multilateralism 2.0: It is here—Are we ready for it? Global Perspectives, 1(1), 17639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellerman, M. (2019). The proliferation of multilateral development banks. The Review of International Organizations, 14(1), 107–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppenjan, J., & Klijn, E.-H. (2004). Managing uncertainties in networks. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer-Mbula, E. (2021). The African development bank: African solutions to African problems? In J. Clifton, D. D. Fuentes, & D. J. Howarth (Eds.), Regional development banks in the world economy (pp. 55–69). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kruser, J. M., Solomon, D., Moy, J. X., Holl, J. L., Viglianti, E. M., Detsky, M. E., & Wiegmann, D. A. (2023). Impact of interprofessional teamwork on aligning intensive care unit care with patient goals: A qualitative study of transactive memory systems. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 20(4), 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K. (2003). Measuring transactive memory systems in the field: Scale development and validation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(4), 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahabir, J. (2013). The effects of lump sum unconditional grants on expenditure and revenue decisions and performance of South African Municipalities. University of Johannesburg (South Africa). [Google Scholar]

- Maroga, J. T., Edoun, E. I., & Pooe, S. (2023). An empirical approach on national exporter development programme (Nedp) on emerging exporters in Gauteng province South Africa. International Journal of Business and Economic Development (IJBED), 11(1), 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marumoagae, M. C. (2017). Addressing the challenge of withdrawal of lump sum retirement benefit payments in South Africa: Lessons from Australia. Comparative and International Law Journal of Southern Africa, 50(1), 129–146. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, R. E., Florin, P., & Stevenson, J. F. (2002). Supporting community-based prevention and health promotion initiatives: Developing effective technical assistance systems. Health Education & Behavior, 29(5), 620–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, R. E., Stone-Wiggins, B., Stevenson, J. F., & Florin, P. (2004). Cultivating capacity: Outcomes of a statewide support system for prevention coalitions. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 27(2), 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadparst Tabas, A., Kansheba, J. M., & Theodoraki, C. (2024). Igniting a knowledge renaissance: Revolutionising entrepreneurial ecosystems with transactive memory systems. Journal of Knowledge Management, 28(11), 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosse, D. (2004). Is good policy unimplementable? Reflections on the ethnography of aid policy and practice. Development and Change, 35(4), 639–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (2007). The knowledge-creating company. Harvard Business Review, 85(7/8), 162. [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka, L., Takeuchi, H., & Umemoto, K. (1996). A theory of organizational knowledge creation. International Journal of Technology Management, 11(7–8), 833–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltokorpi, V. (2008). Transactive memory systems. Review of General Psychology, 12(4), 378–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltokorpi, V. (2014). Transactive memory system coordination mechanisms in organizations: An exploratory case study. Group & Organization Management, 39(4), 444–471. [Google Scholar]

- Pennetta, S., Anglani, F., Reaiche, C., & Boyle, S. (2025). Entrepreneurial agility in a disrupted world: Redefining entrepreneurial resilience for global business success. The Journal of Entrepreneurship, 34(2), 221–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. E. (2008). Competitive advantage: Creating and sustaining superior performance. Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Pressman, J. L., & Wildavsky, A. (1973). Implementation. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Prizzon, A., Greenhill, R., & Mustapha, S. (2017). An ‘age of choice’ for external development finance? Evidence from country case studies. Development Policy Review, 35, O29–O45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashed, M., Uddin, M. K., Islam, M. F., Mohsin, A. K. M., Rahman, S., Kumar, S., & Rana, J. (2025). Building organizational resilience in emerging economies: Strategic insights from Bangladesh. Sustainable Futures, 10, 101327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisen, H., & Garroway, C. (2014). The future of multilateral concessional finance. GIZ. [Google Scholar]

- Sahibzada, S. A., & Mahmood, M. A. (1992). Why most development projects fail in Pakistan? A plausible explanation. The Pakistan Development Review, 31(4), 1111–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schmickl, C., & Kieser, A. (2008). How much do specialists have to learn from each other when they jointly develop radical product innovations? Research Policy, 37(3), 473–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, V. C., Jillani, Z., Malpert, A., Kolodny-Goetz, J., & Wandersman, A. (2022). A scoping review of the evaluation and effectiveness of technical assistance. Implementation Science Communications, 3(1), 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinbergen, J. (1962). Shaping the world economy; suggestions for an international economic policy. Twentieth Century Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, W. H., & Kuo, H. C. (2011). Entrepreneurship policy evaluation and decision analysis for SMEs. Expert Systems with Applications, 38(7), 8343–8351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. (2017). New multilateral development banks: Opportunities and challenges for global governance. Global Policy, 8(1), 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, D. M. (1987). Transactive memory: A contemporary analysis of the group mind. In Theories of group behavior (pp. 185–208). Springer New York. [Google Scholar]

- Weihrich, H. (1982). The TOWS matrix—A tool for situational analysis. Long Range Planning, 15(2), 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2), 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (1991). The African capacity building initiative: Toward improved policy analysis and development management. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (1996). Partnership for capacity building in Africa: Strategy and program of action. A report of the African governors of the World Bank of the President of the World Bank. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2023). Promoting export growth for local development in Africa: Lessons learned from technical assistance. World Bank policy research working paper 10562. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. K., & Davis, D. (2007). Adding new dimensions to case study evaluations: The case of evaluating comprehensive reforms. New Directions for Evaluation, 2007(113), 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y., & Mai, Y. (2013). A contextualized transactive memory system view on how founding teams respond to surprises: Evidence from China. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 7(3), 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pérez-Borbujo, Ó.; Cabeza-Ramírez, L.J.; González-Mohíno, M.; Puccia, A. Leadership, Knowledge Management, and Transactive Memory System in International Technical Assistance: Policy Insights for Entrepreneurial Resilience in Emerging Markets. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 487. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15120487

Pérez-Borbujo Ó, Cabeza-Ramírez LJ, González-Mohíno M, Puccia A. Leadership, Knowledge Management, and Transactive Memory System in International Technical Assistance: Policy Insights for Entrepreneurial Resilience in Emerging Markets. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(12):487. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15120487

Chicago/Turabian StylePérez-Borbujo, Óscar, Luis J. Cabeza-Ramírez, Miguel González-Mohíno, and Angelo Puccia. 2025. "Leadership, Knowledge Management, and Transactive Memory System in International Technical Assistance: Policy Insights for Entrepreneurial Resilience in Emerging Markets" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 12: 487. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15120487

APA StylePérez-Borbujo, Ó., Cabeza-Ramírez, L. J., González-Mohíno, M., & Puccia, A. (2025). Leadership, Knowledge Management, and Transactive Memory System in International Technical Assistance: Policy Insights for Entrepreneurial Resilience in Emerging Markets. Administrative Sciences, 15(12), 487. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15120487