ESG Performance, Donations and Internal Pay Gap—Empirical Evidence Based on Chinese A-Share Listed Companies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

3. Research Hypotheses

3.1. Corporate ESG Performance and Pay Disparity

3.2. Mediating Role of Compensation Incentives

3.3. Mediating Role of Corporate Financialization

3.4. Moderating Role of Charitable Donations

3.5. Moderating Role of Agency Mechanisms

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Research Design

4.2. Key Variables

4.3. Mediating Variables

4.4. Moderating Variables

4.5. Model Specification

4.6. Data Availability

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

5.2. Baseline Regression Results

5.3. Endogeneity Test

5.3.1. Exclude the Influence of Policies

5.3.2. Instrumental Variable Method

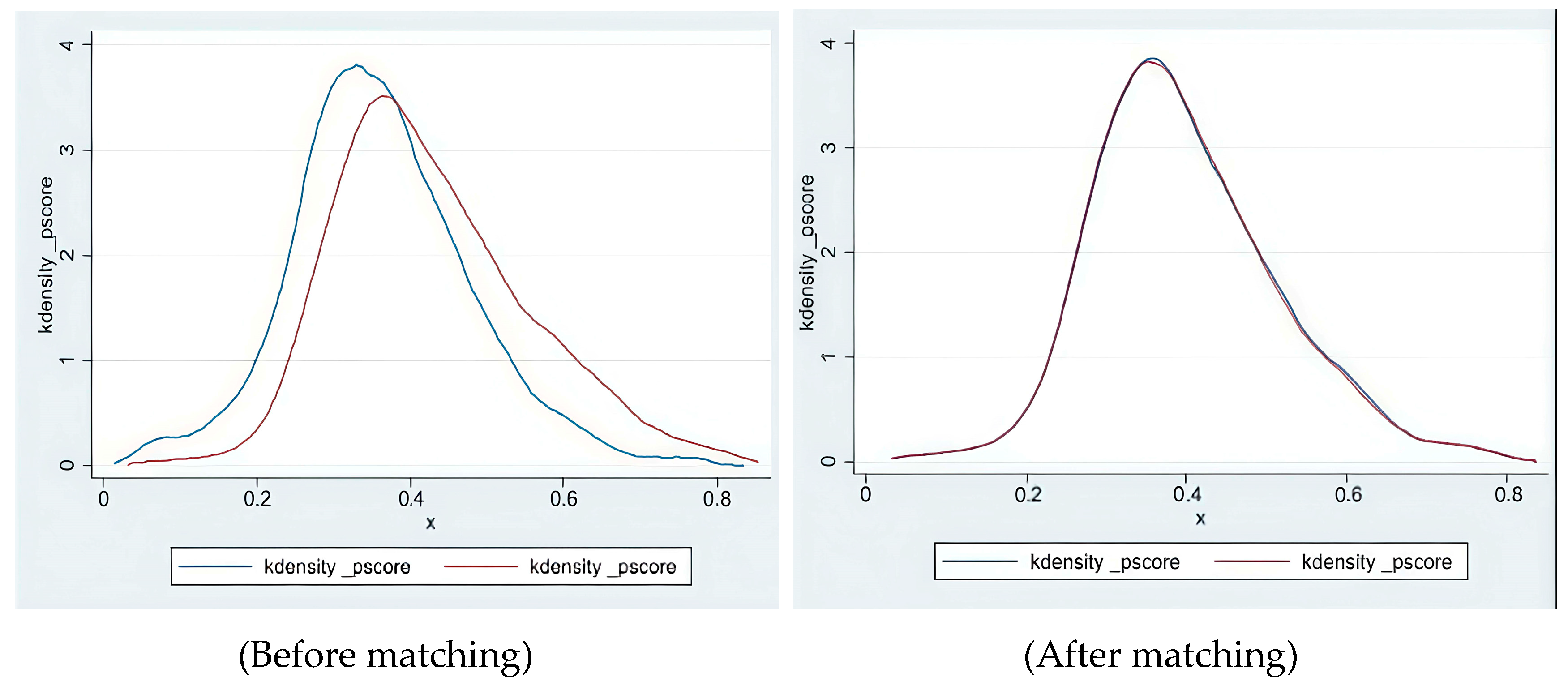

5.3.3. Propensity Score Matching Method

5.3.4. Robustness Checks

5.4. Mechanism Test

5.4.1. Regression-Based Evidence

5.4.2. Formal Mediation Tests

5.5. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.5.1. State-Owned vs. Non-State-Owned Enterprises

5.5.2. Manufacturing vs. Non-Manufacturing Industries

5.6. Further Analysis

5.6.1. Moderating Effects

5.6.2. Dimensional Effects of ESG on Income Disparity

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions and Implications

7.1. Conclusions

7.2. Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Fund | |

|---|---|

| Size | 2.893 × 107 *** |

| (4.893 × 106) | |

| Lev | −3.538 × 107 *** |

| (7.898 × 106) | |

| ROE | 6.172 × 107 *** |

| (1.065 × 107) | |

| Growth | 5.454 × 105 |

| (1.078 × 106) | |

| TOP10 | −5.785 × 105 *** |

| (1.417 × 105) | |

| Dual | −1.987 × 105 |

| (1.926 × 106) | |

| SOE | −1.013 × 107 ** |

| (4.457 × 106) | |

| NetProfit | −2.010 × 107 *** |

| (4.795 × 106) | |

| Board | 4.278 × 106 |

| (9.287 × 106) | |

| lnGDP_per | 1.411 × 107 |

| (1.064 × 107) | |

| Inst | −8.150 × 106 |

| (7.198 × 106) | |

| _cons | −7.196 × 108 *** |

| (1.195 × 108) | |

| id | YES |

| year | YES |

| N | 22,864 |

| R2 | 0.563 |

References

- Alsayegh, M. F., Abdul Rahman, R., & Homayoun, S. (2020). Corporate economic, environmental, and social sustainability performance transformation through ESG disclosure. Sustainability, 12(9), 3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvidsson, S., & Dumay, J. (2022). Corporate ESG reporting quantity, quality and performance: Where to now for environmental policy and practice? Business Strategy and the Environment, 31(3), 1091–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebchuk, L. A., & Fried, J. M. (2003). Executive compensation as an agency problem. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17(3), 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstresser, D., & Philippon, T. (2006). CEO incentives and earnings management. Journal of Financial Economics, 80(3), 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S. J., & Pavelin, S. (2006). Corporate reputation and social performance: The importance of fit. Journal of Management Studies, 43(3), 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherep, O., Cherep, A., Ohrenych, Y., & Helman, V. (2024). Improvement of the management mechanism of the strategy of innovative activities of enterprises. Financial & Credit Activity: Problems of Theory & Practice, 1(54), 471–484. [Google Scholar]

- Conroy, S. A., & Gupta, N. (2019). Disentangling horizontal pay dispersion: Experimental evidence. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(3), 248–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Gesso, C., & Lodhi, R. N. (2025). Theories underlying environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosure: A systematic review of accounting studies. Journal of Accounting Literature, 47(2), 433–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyck, A., Lins, K. V., Roth, L., & Wagner, H. F. (2019). Do institutional investors drive corporate social responsibility? International evidence. Journal of Financial Economics, 131(3), 693–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmans, A., Pu, D., Zhang, C., & Li, L. (2023). Employee satisfaction, labor market flexibility, and stock returns around the world. Management Science. [Google Scholar]

- Ee, M., Chao, C., & Wang, L. (2018). Environmental corporate social responsibility, firm dynamics and wage inequality. International Review of Economics & Finance, 56, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C. (2021). Corporate green bonds. Journal of Financial Economics, 142(2), 499–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, G., Busch, T., & Bassen, A. (2015). ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 5(4), 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D., Chen, X., Zhao, J., & Guo, W. (2023). Tax incentives, factor allocation and within-firm pay gap: Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 60, 1549–1577. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, M., & Geng, X. (2024). The role of ESG performance during times of COVID-19 pandemic. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, S. L., Koch, A., & Starks, L. T. (2021). Firms and social responsibility: A review of ESG and CSR research in corporate finance. Journal of Corporate Finance, 66, 101889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, N., & Grundy, B. D. (2019). Can socially responsible firms survive competition? An analysis of corporate employee matching grant schemes. Review of Finance, 23(1), 199–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F., Du, H., & Yu, B. (2022). Corporate ESG performance and manager misconduct: Evidence from China. International Review of Financial Analysis, 82, 102201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X., Jiang, F., & Zhu, L. (2022). Business strategy, corporate social responsibility, and within-firm pay gap. Economic Modelling, 106, 105703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippner, G. R. (2005). The financialization of the American economy. Socio-Economic Review, 3(2), 173–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, T., & Xie, P. (2024). Fostering enterprise innovation: The impact of China’s pilot free trade zones. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 15(3), 10412–10441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S., Lin, D., & Xiao, H. (2024). Green finance and high-pollution corporate compensation—Empirical evidence from green credit guidelines. Heliyon, 10(8), e27851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Zhao, Y., Ye, C., Xiao, L., & Yun, T. (2024). ESG ratings and the cost of equity capital in China. Energy Economics, 136, 107685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L., Ding, T., Tan, R., & Song, M. (2025). ESG best practices for Chinese companies. In The ESG systems in Chinese enterprises: Theory and practice (pp. 291–349). Springer Nature Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, K. H., & Tomaskovic-Devey, D. (2013). Financialization and US income inequality, 1970–2008. American Journal of Sociology, 118(5), 1284–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J., & Wang, H. (2024). Research on the impact of equity incentive model on enterprise performance: A mediating effect analysis based on executive entrepreneurship. PLoS ONE, 19(4), e0300873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestas, N., Mullen, K. J., Powell, D., von Wachter, T., & Wenger, J. B. (2023). The value of working conditions in the United States and implications for the structure of wages. American Economic Review, 113(7), 2007–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, N., & Kashiramka, S. (2024). Impact of ESG disclosure on firm performance and cost of debt: Empirical evidence from India. Journal of Cleaner Production, 448, 141582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehran, H. (1995). Executive compensation structure, ownership and firm performance. Journal of Financial Economics, 38, 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X., Wan, X., Wang, H., & Li, Y. (2020). The correlation analysis between salary gap and enterprise innovation efficiency based on the entrepreneur psychology. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2002). The competitive advantage of corporate philanthropy. Harvard Business Review, 80(12), 56–68. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Y., Yang, Y., Yang, S., & Si, L. (2021). Does government funding promote or inhibit the financialization of manufacturing enterprises? Evidence from listed Chinese enterprises. North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 58, 101463. [Google Scholar]

- Sadiq, M., Ngo, Q., Pantamee, A., Khudoykulov, K., Ngan, T. T., & Tan, L. P. (2023). The role of environmental social and governance in achieving sustainable development goals: Evidence from ASEAN countries. Economic Research–Ekonomska Istraživanja, 36(1), 170–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J. D. (2014). Pay dispersion. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 521–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockhammer, E. (2010). Financialization and the global economy. Political Economy Research Institute Working Paper, 242(40), 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, L., Ripa, D., Jain, A., Herrero, J., & Leka, S. (2023). The potential of responsible business to promote sustainable work—An analysis of CSR/ESG instruments. Safety Science, 164, 106151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turban, D. B., & Greening, D. W. (1997). Corporate social performance and organizational attractiveness to prospective employees. Academy of Management Journal, 40(3), 658–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., & Li, X. (2023). ESG performance, employee income and pay gap: Evidence from Chinese listed companies. SSRN Working Paper. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W. C., Batten, J. A., Ahmad, A. H., Mohamed-Arshad, S. B., Nordin, S., & Adzis, A. A. (2021). Does ESG certification add firm value? Finance Research Letters, 39, 101593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, J. (2021a). Towards common prosperity: Economic reforms and governance in China. China Economic Journal, 14(2), 127–140. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, J. (2021b). Towards the common prosperity of all: Strategies and policies. Caixin Global. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, W., Li, Y., & Guan, X. (2024). How the executive pay gap affects corporate innovation. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 36(11), 3973–3986. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, P., An, S., & Shen, Y. (2025). Responsible business: Analyzing the impact of corporate ESG on employee pay inequality. Sustainable Futures, 9, 100623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumente, I., & Bistrova, J. (2021). ESG importance for long-term shareholder value creation: Literature vs. practice. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 7(2), 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Type | Variable Name | Variable Symbol | Measurement | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Pay Gap | Gap | Ratio of average executive pay (AMP) to average employee pay (AEP) | Represents the internal wage disparity within the firm, capturing how executive compensation compares to that of ordinary employees |

| Core Independent Variable | ESG Performance | HZ_ESG | HuaZheng ESG rating | Measures the firm’s performance in environmental, social, and governance dimensions, reflecting its sustainability and social responsibility efforts |

| Mediating Variables | Salary Incentives | Salary | Logarithm of total executive pay plus 1 | Reflects the scale of executive compensation used as incentives, aligning management goals with corporate objectives |

| Corporate Financialization | Finratio | Ratio of financial assets to total assets | Indicates the degree to which the firm allocates resources to financial activities instead of core operations | |

| Moderating Variables | Charitable Donation | Phi_D | Donation = 1, No donation = 0 | Captures whether the firm engages in charitable activities, reflecting its social responsibility commitment |

| Management Fee Ratio | Mfee | Ratio of management expenses to operating income | Serves as a proxy for agency costs, indicating the proportion of expenses allocated to management relative to operational output | |

| Control Variables | Company Size | Size | Natural logarithm of total assets | Reflects the scale of the firm’s operations, commonly used to control for size-related effects in corporate performance analysis |

| Debt-to-Asset Ratio | Lev | Year-end total liabilities divided by year-end total assets | Indicates the firm’s leverage level, measuring the proportion of assets financed by debt | |

| Return on Equity | ROE | Net profit divided by average shareholders’ equity | Measures the firm’s profitability relative to shareholder investment, indicating financial performance | |

| Revenue Growth Rate | Growth | Current year’s revenue divided by previous year’s revenue minus 1 | Captures the firm’s annual sales growth, reflecting operational expansion or contraction | |

| Top 10 Shareholders’ Holding Ratio | TOP10 | Number of shares held by the top 10 shareholders divided by total shares | Measures ownership concentration, indicating the level of control exerted by major shareholders | |

| Dual Role of Chairman and CEO | Dual | 1 if the chairman and CEO are the same person, otherwise 0 | Indicates governance structure, specifically whether there is role overlap between board leadership and executive management | |

| State-Owned Enterprise | SOE | 1 for state-controlled enterprises, otherwise 0 | Classifies firms by ownership type, distinguishing between state-owned and non-state-owned enterprises | |

| Net Profit Margin | NetProfit | Net profit divided by operating income | Indicates the firm’s profitability relative to its total revenue, measuring operational efficiency | |

| Number of Directors | Board | Natural logarithm of the number of board directors | Measures board size, which may affect governance effectiveness and decision-making processes | |

| Regional Per Capita GDP | lnGDP_per | Natural logarithm of per capita GDP | Captures regional economic development level, providing contextual control at the macroeconomic level | |

| Proportion of Tertiary Industry Output in the Province | Inst | Tertiary industry output divided by regional total output | Measures the share of the service sector in the regional economy, indicating economic structure and development characteristics |

| VarName | Obs | Mean | SD | Min | Median | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gap | 23,713 | 5.3332 | 3.843 | 0.51 | 4.28 | 25.34 |

| HZ_ESG | 23,713 | 4.1499 | 1.121 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 8.00 |

| Size | 23,713 | 22.2728 | 1.277 | 19.58 | 22.09 | 26.45 |

| Lev | 23,713 | 0.4191 | 0.199 | 0.05 | 0.41 | 0.91 |

| ROE | 23,713 | 0.0642 | 0.130 | −0.93 | 0.07 | 0.44 |

| Growth | 23,713 | 0.1751 | 0.406 | −0.66 | 0.11 | 4.02 |

| TOP10 | 23,713 | 58.5407 | 14.775 | 21.93 | 59.27 | 90.97 |

| Dual | 23,713 | 0.2867 | 0.452 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| SOE | 23,713 | 0.3441 | 0.475 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| NetProfit | 23,713 | 0.0678 | 0.181 | −1.57 | 0.07 | 0.54 |

| Board | 23,713 | 2.1171 | 0.194 | 1.61 | 2.20 | 2.71 |

| lnGDP_per | 23,713 | 11.0934 | 0.466 | 10.00 | 11.04 | 12.16 |

| Inst | 23,713 | 1.8249 | 1.128 | 0.67 | 1.35 | 5.28 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gap | Gap | Gap | Gap | Gap | |

| HZ_ESG | 0.4292 *** | 0.1000 *** | 0.0919 *** | 0.1000 *** | 0.0919 *** |

| (20.9780) | (5.6276) | (5.1528) | (5.6276) | (5.1528) | |

| Controls FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| ID FE | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES |

| Year FE | NO | NO | YES | NO | YES |

| Constant | 3.4221 *** | −12.7840 *** | −16.4893 *** | −12.7840 *** | −16.4893 *** |

| (38.9365) | (−11.9093) | (−5.7400) | (−11.9093) | (−5.7400) | |

| N | 23,713 | 23,713 | 23,713 | 23,713 | 23,713 |

| R2 | 0.018 | −0.139 | −0.132 | −0.139 | −0.132 |

| VARIABLES | Gap |

|---|---|

| HZ_ESG | 0.203 *** |

| (0.021) | |

| treat | 0.381 |

| (0.284) | |

| HZ_ESG_treat | 0.091 |

| (0.067) | |

| Controls FE | YES |

| ID FE | YES |

| Year FE | YES |

| Constant | −17.268 *** |

| (0.744) | |

| N | 23,713 |

| R2 | 0.141 |

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| first | second | |

| VARIABLES | HZ_ESG | Gap |

| fund | 0.004 *** | |

| (4.22) | ||

| HZ_ESG | 3.919 *** | |

| (3.96) | ||

| Controls FE | YES | YES |

| ID FE | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES |

| Constant | −0.884 | 0.584 |

| (−0.69) | (0.11) | |

| N | 22,864 | 22,864 |

| R2 | 0.627 | 0.253 |

| Gap | |

|---|---|

| HZ_ESG | 0.0862 *** |

| (2.8979) | |

| Controls FE | YES |

| ID FE | YES |

| Year FE | YES |

| Constant | 2.2869 |

| (0.4299) | |

| N | 11,532 |

| R2 | 0.719 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gap | Gap | Gap_1 | Gap_2 | Gap | |

| HZ_ESG | 0.0087 ** | 0.0904 *** | |||

| (2.3379) | (3.4098) | ||||

| ESG_PB | 0.0504 *** | ||||

| (7.2447) | |||||

| L.HZ_ESG | 0.0103 | ||||

| (0.5232) | |||||

| Wind_ESG | 0.0761 * | ||||

| (1.8846) | |||||

| Controls FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| ID FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Constant | −25.8231 *** | −12.9869 *** | 5.1982 *** | −27.8366 *** | −16.8893 *** |

| (−4.6027) | (−2.7435) | (8.6498) | (−6.4541) | (−5.1654) | |

| N | 8431 | 12,771 | 22,836 | 22,956 | 19,377 |

| R2 | −0.100 | −0.361 | 0.199 | −0.129 | −0.148 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salary | Gap | Finratio | Gap | |

| HZ_ESG | 0.004 *** | 0.0600 *** | 0.002 *** | 0.209 *** |

| (4.7332) | (3.6177) | (2.5841) | (10.29) | |

| Salary | 2.8599 *** | |||

| (103.7944) | ||||

| Finratio | 1.508 *** | |||

| (5.70) | ||||

| Controls FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| ID FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Constant | 7.536 *** | −30.2919 *** | 0.301 *** | −17.554 *** |

| (2.4989) | (−49.4214) | (2.9642) | (−23.63) | |

| N | 23,688 | 23,568 | 23,713 | 23,294 |

| R2 | 0.789 | 0.409 | 0.700 | 0.14 |

| Salary Incentive Path | Corporate Financialization Path | |

|---|---|---|

| Indirect Effect | 0.0114 *** | 0.0030 *** |

| 95% CI | [0.0041, 0.0188] | [0.0010, 0.0055] |

| Direct Effect | 0.0486 *** | 0.2060 *** |

| 95% CI | [0.0352, 0.0621] | [0.1925, 0.2195] |

| Total Effect | 0.0600 *** | 0.2090 *** |

| 95% CI | [0.0466, 0.0735] | [0.1955, 0.2225] |

| Bootstrap Reps | 1000 | 1000 |

| State-Owned Enterprises | Non-State-Owned Enterprises | Manufacturing | Non-Manufacturing Sector | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gap | Gap | Gap | Gap | |

| HZ_ESG | 0.092 *** | 0.114 *** | 0.111 *** | 0.068 ** |

| (0.031) | (0.022) | (0.022) | (0.031) | |

| Controls FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| ID FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Constant | −4.445 | −15.711 *** | −18.384 *** | 0.857 |

| (4.677) | (4.207) | (4.413) | (4.791) | |

| N | 8166.000 | 15,547.000 | 15,672.000 | 8041.000 |

| R2 | 0.218 | 0.326 | 0.302 | 0.174 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gap | Gap | Gap | Gap | |

| HZ_ESG | 0.1713 *** | 0.2035 *** | 0.2035 *** | 0.2277 *** |

| (6.2556) | (6.4310) | (9.9939) | (10.7115) | |

| Phi_D | 0.1169 * | 0.7042 ** | ||

| (1.8940) | (2.3798) | |||

| ESG_Phi_D | −0.1247 ** | |||

| (−2.0293) | ||||

| Mfee | −0.7309 ** | |||

| (−2.1236) | ||||

| ESG_Mfee | −0.3001 *** | |||

| (−3.4505) | ||||

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| ID FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Constant | −17.7412 *** | −17.9117 *** | −17.5070 *** | −17.3485 *** |

| (−23.7530) | (−23.8324) | (−22.9056) | (−22.8563) | |

| N | 23713 | 23713 | 23713 | 23713 |

| R2 | 0.137 | 0.137 | 0.137 | 0.137 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Gap | Gap | Gap |

| E | 0.0662 *** | ||

| (0.0231) | |||

| S | −0.014 | ||

| (−0.44) | |||

| G | 0.092 *** | ||

| (2.99) | |||

| Controls | YES | YES | YES |

| ID FE | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES |

| Constant | −10.13 * | −6.682 | −11.330 * |

| (5.864) | (−1.07) | (−1.91) | |

| N | 2138 | 2158 | 2161 |

| R2 | 0.057 | 0.055 | 0.054 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, C.; Jiao, Y. ESG Performance, Donations and Internal Pay Gap—Empirical Evidence Based on Chinese A-Share Listed Companies. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 483. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15120483

Liu C, Jiao Y. ESG Performance, Donations and Internal Pay Gap—Empirical Evidence Based on Chinese A-Share Listed Companies. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(12):483. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15120483

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Chong, and Yan Jiao. 2025. "ESG Performance, Donations and Internal Pay Gap—Empirical Evidence Based on Chinese A-Share Listed Companies" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 12: 483. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15120483

APA StyleLiu, C., & Jiao, Y. (2025). ESG Performance, Donations and Internal Pay Gap—Empirical Evidence Based on Chinese A-Share Listed Companies. Administrative Sciences, 15(12), 483. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15120483