When Does Authenticity Benefit Employee Well-Being: A Relational Framework of Authenticity at Work

Abstract

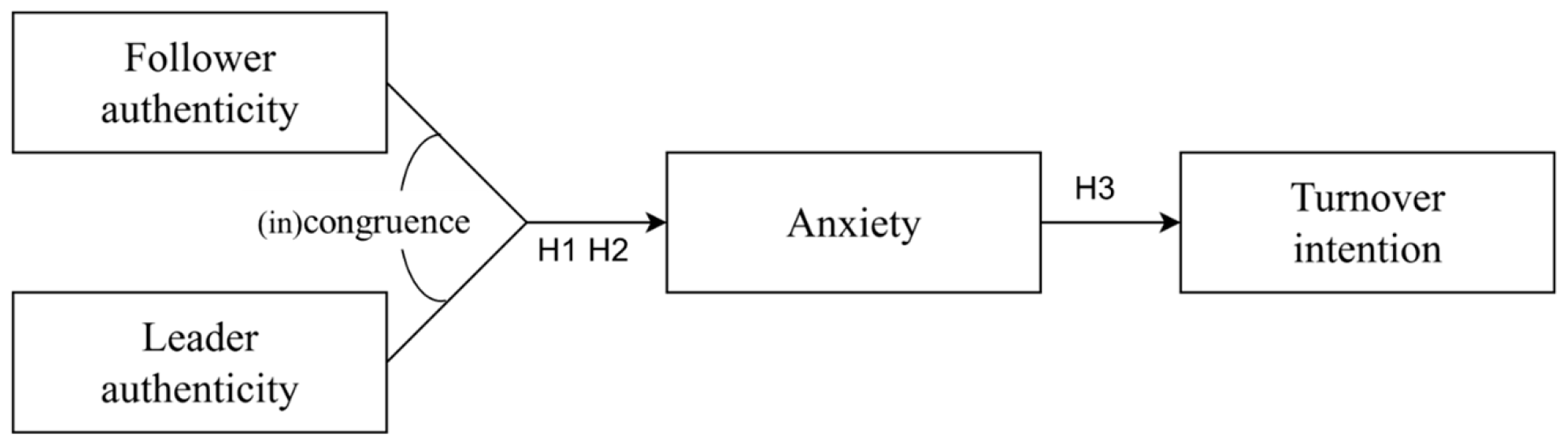

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Authenticity at Work

2.2. Authenticity (In)congruence

2.3. Consequences for Turnover Intentions

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample

3.2. Measures

3.3. Polynomial Regression Analysis

3.4. Indirect Effect on Turnover Intentions

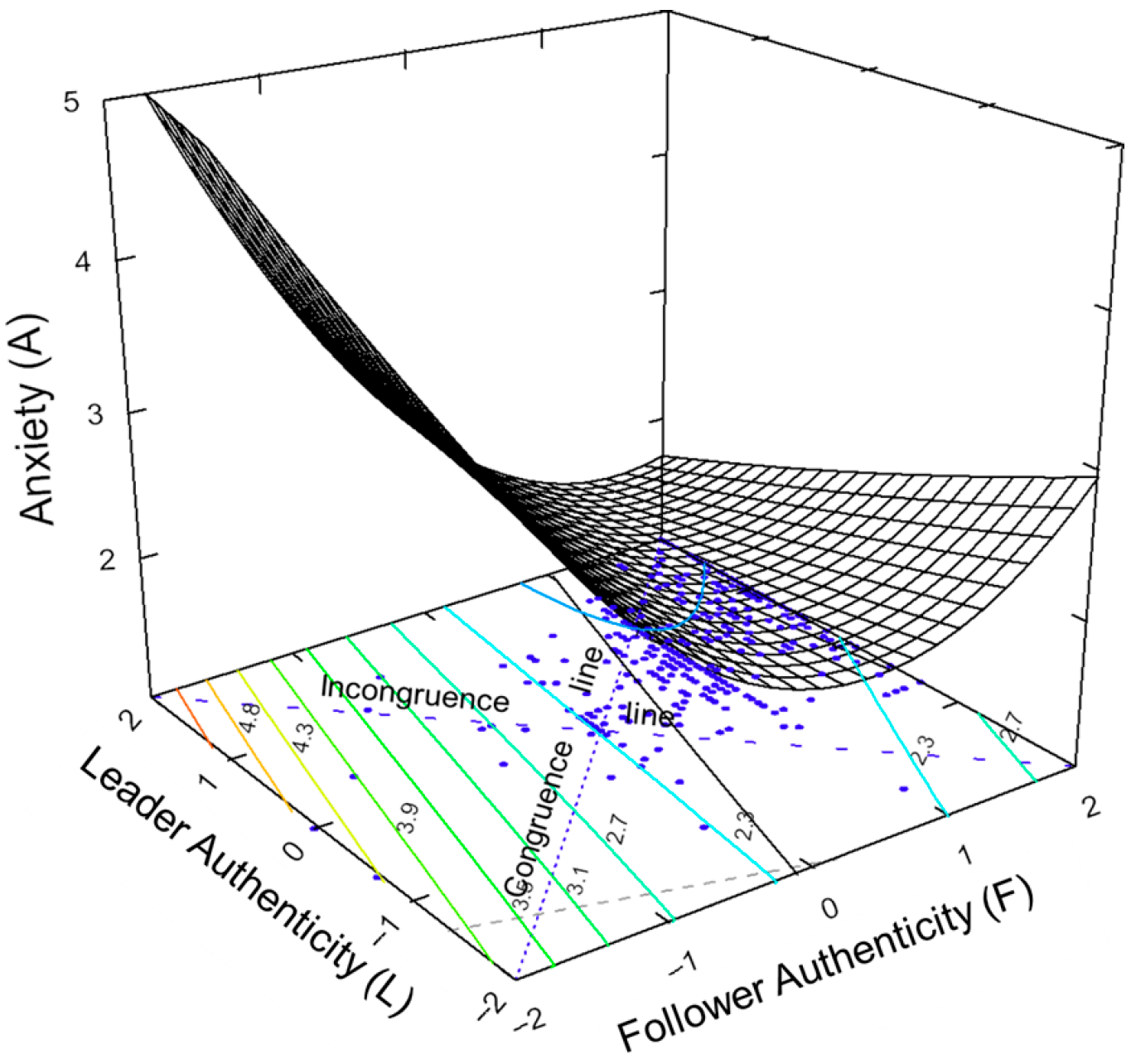

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Main Findings

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The Result of Sensitivity Analysis Using the z-Standardized Scale

| Variables | Anxiety | Turnover Intention | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | |

| Constant | 2.014 *** | 0.242 | 1.854 *** | 0.473 |

| Control | ||||

| Male | 0.026 | 0.061 | −0.184 * | 0.089 |

| Age | −0.007 | 0.007 | 0.015 | 0.010 |

| Education | −0.144 ** | 0.049 | −0.097 | 0.089 |

| Job tenure | 0.011 | 0.007 | −0.031 ** | 0.011 |

| Polynomial terms | ||||

| b1 Follower authenticity (F) | −0.347 *** | 0.038 | −0.445 *** | 0.077 |

| b2 Leader authenticity (L) | 0.002 | 0.039 | −0.025 | 0.059 |

| b3 F2 | 0.131 *** | 0.032 | 0.208 ** | 0.066 |

| b4 F*L | −0.087 | 0.048 | −0.222 ** | 0.064 |

| b5 L2 | 0.007 | 0.028 | 0.046 | 0.046 |

| Mediator | ||||

| β Anxiety | 0.310 *** | 0.084 | ||

| R2 | 0.374 *** | 0.051 | 0.429 *** | 0.050 |

| Response surface parameters | ||||

| Slope of Congruence line (a1 = b1 + b2) | −0.346 *** | 0.041 | ||

| Curvature of Congruence line (a2 = b3 + b4 + b5) | 0.050 | 0.037 | ||

| Slope of Incongruence line (a3 = b1 − b2) | −0.349 *** | 0.065 | ||

| Curvature of Incongruence line (a4 = b3 − b4 + b5) | 0.225 ** | 0.084 | ||

References

- Aldrich, H., & Herker, D. (1977). Boundary spanning roles and organization structure. Academy of Management Review, 2(2), 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, D. R., & Flynn, F. J. (2007). What breaks a leader: The curvilinear relation between assertiveness and leadership. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(2), 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aubouin-Bonnaventure, J., Fouquereau, E., Coillot, H., Lahiani, F.-J., & Chevalier, S. (2023). A new gain spiral at work: Relationships between virtuous organizational practices, psychological capital, and well-being of workers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B. J., & Gardner, W. L. (2005). Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 16(3), 315–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Biermeier-Hanson, B., Wynne, K. T., Thrasher, G., & Lyons, J. B. (2021). Modeling the joint effect of leader and follower authenticity on work and non-work outcomes. The Journal of Psychology, 155(2), 140–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, L. (2021). Does person organization fit and person-job fit mediate the relationship between public service motivation and work stress among U.S. federal employees? Administrative Sciences, 11(2), 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cable, D. M., Gino, F., & Staats, B. R. (2013). Breaking them in or eliciting their best? Reframing socialization around newcomers’ authentic self-expression. Administrative Science Quarterly, 58(1), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, R. D. (1983). Person-environment fit: Past, present, and future. In C. L. Cooper (Ed.), Stress research: Issues for the eighties (pp. 37–71). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, S. E., Hewlin, P. F., Roberts, L. M., Buckman, B. R., Leroy, H., Steckler, E. L., Ostermeier, K., & Cooper, D. (2019). Being your true self at work: Integrating the fragmented research on authenticity in organizations. Academy of Management Annals, 13(2), 633–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H. Y., & Chen, C. C. (2025). Response surface models in science and technology. Applied Sciences, 15(13), 7206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D. A., & Maxwell, S. E. (2003). Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112(4), 558–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J. R. (2002). Alternatives to difference scores: Polynomial regression analysis and response surface methodology. In F. Drasgow, & N. W. Schmitt (Eds.), Advances in measurement and data analysis (pp. 350–400). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, J. R., & Cable, D. M. (2009). The value of value congruence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(3), 654–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J. R., Caplan, R. D., & Harrison, R. V. (1996). Person-environment fit theory: Conceptual and methodological issues. In C. L. Cooper, & I. T. Robertson (Eds.), International review of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 11, pp. 289–347). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, J. R., & Cooper, C. (1990). The person-environment fit approach to stress: Recurring problems and some suggested solutions. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 11(4), 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J. R., & Parry, M. E. (1993). On the use of polynomial regression equations as an alternative to difference scores in organizational research. Academy of Management Journal, 36(6), 1577–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epitropaki, O., Kark, R., Mainemelis, C., & Lord, R. G. (2017). Leadership and followership identity processes: A multilevel review. The Leadership Quarterly, 28(1), 104–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S., Lee, Y. E., Yoon, S., Dimotakis, N., Koopman, J., & Tepper, B. J. (2024). “I Didn’t See That Coming!” A daily investigation of the effects of as-expected and un-expected workload levels. Personnel Psychology, 77(3), 1311–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, W. L., Cogliser, C. C., Davis, K. M., & Dickens, M. P. (2011). Authentic leadership: A review of the literature and research agenda. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(6), 1120–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A. M., & Schwartz, B. (2011). Too much of a good thing: The challenge and opportunity of the inverted U. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 6(1), 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanisch, K. A., & Hulin, C. L. (1991). General attitudes and organizational withdrawal: An evaluation of a causal model. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 39(1), 110–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannah, S. T., Bluhm, D., & Avolio, B. J. (2024). Hierarchical leader-leader fit: Examining authentic leader dyads and implications for junior leader outcomes. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 31(4), 453–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannah, S. T., Lester, P. B., & Vogelgesang, G. R. (2005). Moral leadership: Explicating the moral component of authentic leadership. In W. L. Gardner, B. J. Avolio, & F. O. Walumbwa (Eds.), Authentic leadership theory and practice: Origins, effects and development (pp. 43–81). Elsevier Science. [Google Scholar]

- Harman, H. (1976). Modern factor analysis. University of Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Harter, S. (2002). Authenticity. In C. R. Snyder, & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 382–394). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hewlin, P. F., Karelaia, N., Kouchaki, M., & Sedikides, C. (2020). Authenticity at work: Its shapes, triggers, and consequences. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 158, 80–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E., & Shirom, A. (2001). Conservation of resources theory: Applications to stress and management in the workplace. In R. T. Golembiewski (Ed.), Handbook of organizational behavior (pp. 57–80). Marcel Dekker. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, A. J. (1993). The importance of fit between individual values and organisational culture in the greening of industry. Business Strategy and the Environment, 2(4), 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, L. (2025). Authenticity and woman’s leadership: A qualitative study of professional business services in the UK. Journal of Work-Applied Management, 17(1), 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M. C., & Cogswell, J. E. (2023). A meta-analysis of polychronicity: Applying modern perspectives of multitasking and person-environment fit. Organizational Psychology Review, 13(3), 315–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilies, R., Morgeson, F. P., & Nahrgang, J. D. (2005). Authentic leadership and eudaemonic well-being: Understanding leader-follower outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 16(3), 373–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J. M., Patel, P. C., & Messersmith, J. G. (2013). High-performance work systems and job control: Consequences for anxiety, role overload, and turnover intentions. Journal of Management, 39(6), 1699–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jex, S. M. (1998). Stress and job performance: Theory, research, and implications for managerial practice. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, R. L., Wolfe, D., Quinn, R., Snoek, J., & Rosenthal, R. (1964). Organizational stress: Studies in role conflict and ambiguity. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J., Yammarino, F. J., Dionne, S. D., Eckardt, R., Cheong, M., Tsai, C.-Y., Guo, J., & Park, J. W. (2020). State-of-the-science review of leader-follower dyads research. The Leadership Quarterly, 31(1), 101306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkman, B. L., Chen, G., Farh, J.-L., Chen, Z. X., & Lowe, K. B. (2009). Individual power distance orientation and follower reactions to transformational leaders: A cross-level, cross-cultural examination. Academy of Management Journal, 52(4), 744–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, J., & Mainiero, L. (2021). Authentic talent development in women leaders who opted out: Discovering authenticity, balance, and challenge through the Kaleidoscope Career Model. Administrative Sciences, 11(2), 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof-Brown, A., Schneider, B., & Su, R. (2023). Person-organization fit theory and research: Conundrums, conclusions, and calls to action. Personnel Psychology, 76(2), 375–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof-Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., & Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of person-job, person-organization, person-group, and person-supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology, 58(2), 281–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntz, J. R. C., & Abbott, M. (2017). Authenticity at work: A moderated mediation analysis. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 25(5), 789–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J., Huo, Y., Wong, I. A., & Yuan, B. (2023). How (in)congruence of leader–follower learning goal orientation influences leader–member exchange and employee innovation. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 35(7), 2545–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, H., Anseel, F., Gardner, W. L., & Sels, L. (2015). Authentic leadership, authentic followership, basic need satisfaction, and work role performance: A cross-level study. Journal of Management, 41(6), 1677–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., & Wang, Y. (2016). Reliability and validity of the individual authenticity measure at work for Chinese employees. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 24, 454–458. [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales (2nd ed.). Psychology Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, F., & Avolio, B. J. (2003). Authentic leadership development. In K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton, & R. E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship: Foundations of a new discipline (pp. 241–261). Berrett-Koehler Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Lux, A. A., & Lowe, K. B. (2024). Authentic leadership: 20-Year review editorial. Journal of Management & Organization, 30(6), 1634–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marstand, A. F., Martin, R., & Epitropaki, O. (2017). Complementary person-supervisor fit: An investigation of supplies-values (S-V) fit, leader-member exchange (LMX) and work outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 28(3), 418–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R., Guillaume, Y., Thomas, G., Lee, A., & Epitropaki, O. (2016). Leader-member exchange (LMX) and performance: A meta-analytic review. Personnel Psychology, 69(1), 67–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, L. R., Sawyer, K. B., Thoroughgood, C. N., Ruggs, E. N., & Smith, N. A. (2017). The importance of being ‘me’: The relation between authentic identity expression and transgender employees’ work-related attitudes and experiences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(2), 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maunz, L. A., & Glaser, J. (2023). Does being authentic promote self-actualization at work? Examining the links between work-related resources, authenticity at work, and occupational self-actualization. Journal of Business and Psychology, 38, 347–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, D. R., Chan, A. Y. L., Hodges, T. D., & Avolio, B. J. (2003). Developing the moral component of authentic leadership. Organizational Dynamics, 32(3), 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ménard, J., & Brunet, L. (2011). Authenticity and well-being in the workplace: A mediation model. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 26(4), 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minson, J. A., & Monin, B. (2012). Do-gooder derogation: Disparaging morally motivated minorities to defuse anticipated reproach. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobley, W. H., Horner, S. O., & Hollingsworth, A. T. (1978). An evaluation of precursors of hospital employee turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 63, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monin, B., Sawyer, P. J., & Marquez, M. J. (2008). The rejection of moral rebels: Resenting those who do the right thing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(1), 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchinsky, P. M., & Monahan, C. J. (1987). What is person-environment congruence? Supplementary versus complementary models of fit. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 31(3), 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumford, M. D., & Fried, Y. (2014). Give them what they want or give them what they need? Ideology in the study of leadership. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(5), 622–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2011). Mplus user’s guide (6th ed.). Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Neider, L. L., & Schriesheim, C. A. (2011). The Authentic Leadership Inventory (ALI): Development and empirical tests. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(6), 1146–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, C., Liang, F., Meng, X., & Liu, Y. (2020). The inverted U-shaped relationship between authentic leadership and unethical pro-organizational behavior. Social Behavior and Personality, 48(11), e9416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, I.-S., Guay, R. P., Kim, K., Harold, C. M., Lee, J.-H., Heo, C.-G., & Shin, K.-H. (2014). Fit happens globally: A meta-analytic comparison of the relationships of person–environment fit dimensions with work attitudes and performance across East Asia, Europe, and North America. Personnel Psychology, 67(1), 99–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, D. K. (2003). The relationship between ethical pressure, relativistic moral beliefs and organizational commitment. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 18(6), 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillemer, J. (2024). Strategic authenticity: Signaling authenticity without undermining professional image in workplace interactions. Organization Science, 35(5), 1641–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, K. J., & Selig, J. P. (2012). Advantages of Monte Carlo confidence intervals for indirect effects. Communication Methods and Measures, 6(2), 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, J. E., Wang, D., Yeo, J. S. E., Khong, Z. Y., & Tan, C. S. (2023). Perceived authenticity, Machiavellianism, and psychological functioning: An inter-domain and cross-cultural investigation. Personality and Individual Differences, 204, 112049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, I. R., Palma-Moreira, A., & Au-Yong-Oliveira, M. (2025). Let me know what kind of leader you are, and I will tell you if I stay: The role of well-being in the relationship between leadership and turnover intentions. Administrative Sciences, 15(7), 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, C. C., Dimotakis, N., Cole, M. S., Taylor, S. G., Simon, L. S., Smith, T. A., & Reina, C. S. (2020). When challenges hinder: An investigation of when and how challenge stressors impact employee outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(10), 1181–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R. S., Lousã, E. P., Sá, M. M., & Cordeiro, J. A. (2023). First, be a good citizen: Organizational citizenship behaviors, well-being at work and the moderating role of leadership styles. Behavioral Sciences, 13(10), 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmader, T., & Sedikides, C. (2018). State authenticity as fit to environment: The implications of social identity for fit, authenticity, and self-segregation. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 22(3), 228–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwepker, C. H., Ferrell, O. C., & Ingram, T. N. (1997). The influence of ethical climate and ethical conflict on role stress in the sales force. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 25(2), 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedikides, C., & Schlegel, R. J. (2024). Distilling the concept of authenticity. Nature Reviews Psychology, 3(8), 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, E., & Davis, W. E. (2021). Authenticity predicts positive interpersonal relationship quality at low, but not high, levels of psychopathy. Personality and Individual Differences, 182, 111072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanock, L. R., Baran, B. E., Gentry, W. A., Pattison, S. C., & Heggestad, E. D. (2010). Polynomial regression with response surface analysis: A powerful approach for examining moderation and overcoming limitations of difference scores. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(4), 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L., Wang, Y., & Zhao, Y. (2021). How employee authenticity shapes work attitudes and behaviors: The mediating role of psychological capital and the moderating role of leader authenticity. Journal of Business and Psychology, 36(6), 1125–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, R. P., & Lounsbury, J. W. (2009). Turnover process models: Review and synthesis of a conceptual literature. Human Resource Management Review, 19(4), 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stouten, J., Van Dijke, M., Mayer, D. M., De Cremer, D., & Euwema, M. C. (2013). Can a leader be seen as too ethical? The curvilinear effects of ethical leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(5), 680–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, A. (2020). Living the good life: A meta-analysis of authenticity, well-being and engagement. Personality and Individual Differences, 153, 109645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-Y., Kim, J., Jin, F., Jun, M., Cheong, M., & Yammarino, F. J. (2022). Polynomial regression analysis and response surface methodology in leadership research. The Leadership Quarterly, 33(1), 101592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bosch, R., & Taris, T. W. (2014). Authenticity at work: Development and validation of an individual authenticity measure at work. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bosch, R., Taris, T. W., Wilmar, B., Schaufeli, W. B., Peeters, M. C. W., & Reijseger, G. (2019). Authenticity at work: A matter of fit? The Journal of Psychology, 153(2), 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vianen, A. E. M. (2018). Person-environment fit: A review of its basic tenets. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 75–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vleugels, W. (2024). Person-environment misfit. In M. Bal (Ed.), Elgar encyclopedia of organizational psychology (pp. 498–504). Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F. O., Avolio, B. J., Gardner, W. L., Wernsing, T. S., & Peterson, S. J. (2008). Authentic leadership: Development and validation of a theory-based measure. Journal of Management, 34(1), 89–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Womick, J., Foltz, R. M., & King, L. A. (2019). ‘Releasing the beast within’? Authenticity, well-being, and the dark tetrad. Personality and Individual Differences, 137, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A. M., Linley, P. A., Maltby, J., Baliousis, M., & Joseph, S. (2008). The authentic personality: A theoretical and empirical conceptualization and the development of the authenticity scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55(3), 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D., & Takahashi, K. (2022). Economic, organizational and psychological determinants of early turnover: Evidence from a pharmaceutical company in China. Employee Relations, 44(2), 356–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S., Koopman, J., Dimotakis, N., Simon, L. S., Liang, L. H., Ni, D., Zheng, X., Fu, S. Q., Lee, Y. E., Tang, P. M., Ng, C. T. S., Bush, J. T., Darden, T. R., Forrester, J. K., Tepper, B. J., & Brown, D. J. (2023). Consistent and low is the only way to go: A polynomial regression approach to the effect of abusive supervision inconsistency. Journal of Applied Psychology, 108(10), 1619–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Guo, Y., Zhang, M., Xu, S., Liu, X., & Newman, A. (2021). Antecedents and outcomes of authentic leadership across culture: A meta-analytic review. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 39, 1399–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y. F., Sluss, D. M., & Badura, K. L. (2024). Subordinate-to-supervisor relational identification: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 109(9), 1431–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | N | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sex (male) | 412 | 0.434 | 0.496 | |||||||

| 2 | Age | 409 | 37.112 | 6.831 | 0.075 | ||||||

| 3 | Tenure | 410 | 12.196 | 6.413 | −0.044 | 0.792 *** | |||||

| 4 | Education | 412 | 2.940 | 0.494 | 0.102 * | −0.287 *** | −0.282 *** | ||||

| 5 | Follower authenticity | 412 | 4.669 | 0.978 | 0.066 | 0.070 | 0.039 | 0.082 | |||

| 6 | Leader authenticity | 412 | 4.168 | 0.715 | 0.168 *** | −0.098 * | −0.071 | 0.129 ** | 0.317 *** | ||

| 7 | Anxiety | 412 | 1.595 | 0.695 | −0.009 | 0.014 | 0.067 | −0.151 ** | −0.533 *** | −0.112 * | |

| 8 | Turnover intention | 412 | 2.340 | 1.137 | −0.079 | −0.055 | −0.073 | −0.092 | −0.557 *** | −0.147 ** | 0.479 *** |

| Variables | Anxiety | Turnover Intention | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | |

| Constant | 2.232 *** | 0.254 | 2.174 *** | 0.467 |

| Control | ||||

| Male | 0.026 | 0.061 | −0.184 * | 0.089 |

| Age | −0.007 | 0.007 | 0.015 | 0.010 |

| Education | −0.144 ** | 0.049 | −0.098 | 0.089 |

| Job tenure | 0.011 | 0.007 | −0.031 ** | 0.011 |

| Polynomial terms | ||||

| b1 Follower authenticity (F) | −0.591 *** | 0.126 | −0.568 * | 0.242 |

| b2 Leader authenticity (L) | 0.056 | 0.111 | −0.033 | 0.198 |

| b3 F2 | 0.307 *** | 0.076 | 0.488 ** | 0.155 |

| b4 F × L | −0.185 | 0.103 | −0.472 ** | 0.137 |

| b5 L2 | 0.012 | 0.054 | 0.088 | 0.089 |

| Mediator | ||||

| β Anxiety | 0.310 *** | 0.084 | ||

| R2 | 0.374 *** | 0.052 | 0.429 *** | 0.050 |

| Response surface parameters | ||||

| Slope of Congruence line (a1 = b1 + b2) | −0.536 *** | 0.158 | ||

| Curvature of Congruence line (a2 = b3 + b4 + b5) | 0.135 | 0.079 | ||

| Slope of Incongruence line (a3 = b1 − b2) | −0.647 *** | 0.178 | ||

| Curvature of Incongruence line (a4 = b3 − b4 + b5) | 0.504 ** | 0.181 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xie, D.; Yang, Y. When Does Authenticity Benefit Employee Well-Being: A Relational Framework of Authenticity at Work. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 449. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110449

Xie D, Yang Y. When Does Authenticity Benefit Employee Well-Being: A Relational Framework of Authenticity at Work. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(11):449. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110449

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Di, and Ying Yang. 2025. "When Does Authenticity Benefit Employee Well-Being: A Relational Framework of Authenticity at Work" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 11: 449. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110449

APA StyleXie, D., & Yang, Y. (2025). When Does Authenticity Benefit Employee Well-Being: A Relational Framework of Authenticity at Work. Administrative Sciences, 15(11), 449. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110449