Independent candidate Călin Georgescu won the first round of the Romanian presidential election with a preliminary score of 22.95%, beating established political figures such as Marcel Ciolacu, Elena Lasconi, and Nicolae Ciucă. This unexpected result reflects a spectacular rise, largely supported by an intense campaign conducted on TikTok, a platform that has become a main vector of electoral mobilization in Romania. The surprise candidate was initially the target of accusations of sympathy for Russia, but he firmly denied the Russophile label, generating debate and confusion among his electorate. However, his digital communication strategy managed to capture the attention of a significant number of voters.

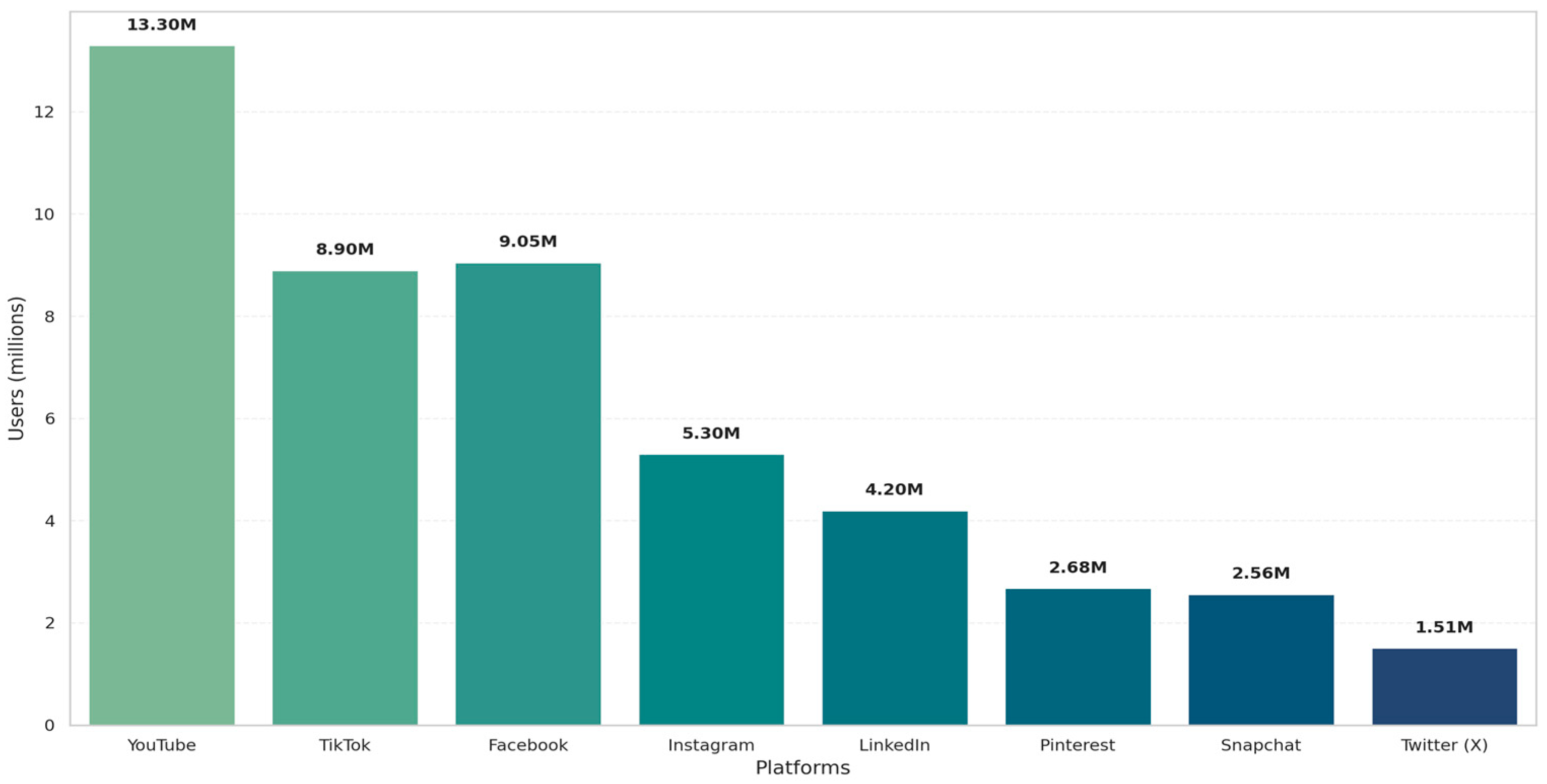

The independent candidate’s campaign focused almost entirely on TikTok, which allowed him to connect with a younger and more active online audience. TikTok, which has become the second most used social media platform in Central Europe, is playing an increasingly important role in Romania, with Romanians spending an average of 32 h and 30 min per month on TikTok, more than on any other social media platform. The success of the winner of the first round of elections has not been without controversy. Attributing a significant role to TikTok in mobilizing voters has sparked debates about the potential risks associated with digital influence. There have also been allegations of possible Russian involvement in his campaign, which has raised concerns about the manipulation of public opinion through social media. TikTok’s rapid growth in Romania and its significant influence on electoral behavior indicate that the platform has become a key tool in mobilizing voters. In the context of the 2024 presidential elections, TikTok has demonstrated that it can change electoral dynamics, attracting the attention not only of local political actors but also of international institutions concerned with protecting the integrity of democratic processes.

Two days before the second round of the presidential elections, the Constitutional Court of Romania took an unprecedented decision to annul the results of the first round of the presidential elections due to suspicions of foreign interference and electoral manipulation. This decision was influenced by documents declassified by the incumbent President, Klaus Iohannis, on 4 December, which confirmed the involvement of a foreign state actor. Accusations of disinformation and cyber manipulation were raised, including in the meetings of the Supreme Council for National Defense. The decision to annul the first round highlighted the vulnerabilities of the electoral process and generated a major political crisis: the leaders of the PSD and PNL suffered significant image losses, with Marcel Ciolacu and Nicolae Ciucă resigning from their positions as leaders of the PSD and PNL, respectively.

3.1. Analysis of the Procedures Through Which the Electoral Message Was Propagated on TikTok

If in previous discussions, we discussed aspects related to keywords and ways to set a target audience, which manifests itself differently when interacting with content that they resonate with, then the entire strategy was extremely well put together. The next stage is choosing the platform which at this moment is making video materials viral in an impressive manner, especially since the manipulation and distribution of content by artificially creating it under the guise of an electoral campaign can be overlooked. Therefore, by using resources available online, it is possible to build an internal solution through which views can be artificially increased and reactions and interactions can be amplified for materials published on TikTok. The algorithm redirects content depending on the retention rate, the interaction of users with that content, but also how they manifest themselves about the material viewed (like, share, comment, tag, etc.).

We can say that the idea was to build a series of TikTok accounts or take over existing ones, subjecting them to a series of iterations based on automation scripts that execute commands in a terminal to artificially increase views. Through this mechanism, the number of views can increase exponentially, reaching significant values, up to a million views in less than 24 h. The script sends requests to TikTok servers, simulating authentic interactions and using security keys similar to those generated by the platform. To support the process, a database is used that contains fictitious or recently created accounts without being owned by a real person, configured to appear authentic (

Çömezoğlu et al., 2024). These accounts include elements that give them credibility, such as well-chosen profile photos and videos that mimic daily activities. These accounts generate views, comments, and other forms of seemingly organic traffic, thus amplifying the distribution of the content.

Once a video reaches a certain threshold of views, TikTok activates its automatic search feature, suggesting users explore topics related to the promoted content. This mechanism triggers a “snowball” effect, in which user engagement contributes to an additional increase in the popularity of the content. Users who interact with the videos (through comments, likes, or shares) feed the algorithm, which further prioritizes that content.

Artificially amplified interactions create the illusion of social consensus and broad support for the promoted topic or candidate. The generalized emotions and themes addressed by a candidate in his speech play an important role in capturing the public’s attention and generating a sense of collective support. This technique can be used to build a credible profile of a political candidate, creating the perception of massive support from voters. The perceived popularity of a candidate can influence public opinion, causing voters to align with what appears to be a majority choice. Strategic comments, marked and amplified by automatic likes, contribute to the consolidation of this image. We can say that such a method was also used in the case of Facebook 10–15 years ago when a user wanted to artificially and quickly increase the number of likes or followers of a Facebook page. The procedure was carried out through the browser console and the injection of a Javascript script to retrieve the user ID and the page ID and automatically send an invite to all pages in the Facebook property account. A similar procedure was also carried out on Facebook when a Facebook Group community wanted to grow, and adding new users was blocked by Facebook security services, where the same script changed the method from “Invite” to “Add new member”, a similar action, but performed without being counted by Facebook. Also, during the Romanian elections from 2010 to 2014, promotion campaigns took place on social media, especially Facebook, which was the most popular social networking network, and certain applications which had access to the Facebook API and the friend list, which were called extremely harmless, including applications for shrinking users’ foreheads, games and applications through which the user found out which celebrity he matches, which animal, zodiac sign, if he will be successful in money, love, etc., in the next year.

The applications iterated the user’s data, returned a response to Facebook regarding the request made, and subsequently an invitation was sent to all the user’s other friends. What those who used such applications did not know was the fact that they were built to generate an impact, traffic, views, and advertising earnings, but most importantly “Likes”. It may seem strange, but users who interacted with those interfaces or web applications in the back-end were hidden like buttons, of political pages and candidates, products, services, etc. When a user followed the procedure by clicking on launch the application, a clear message was sent to the application server to return a response, but at the same time, the user was given a like to hundreds of Facebook pages hidden in the source code from the Algorithm 1.

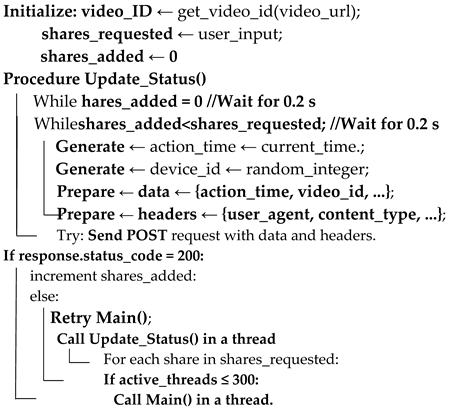

| Algorithm 1: Pseudocode TikTok Views Automation. |

![Admsci 15 00448 i001 Admsci 15 00448 i001]() |

In a word, the same principle of boosting voters was also used in previous electoral campaigns, even if their media coverage was not extremely acidic, either due to the lack of involvement of the IT&C environment or because these methods were not known. The method presented previously was also exposed by the media trusts in Romania, but at the level at which it generated impact in the online environment and that financial income was brought to those who created the application through advertising/ads campaigns, without exposing that they were also used for political purposes. If we return to the TikTok platform, through a simple script written in Python 3.13.2, we can demonstrate that multiple requests to a server can be simulated to fictitiously increase traffic and automatically generate views. It is a type of experiment already tested in small groups of programmers and, this time, the exposure of how things happened is purely educational to expose to the public the main reasons why the content on TikTok has gravitated around the independent candidate.

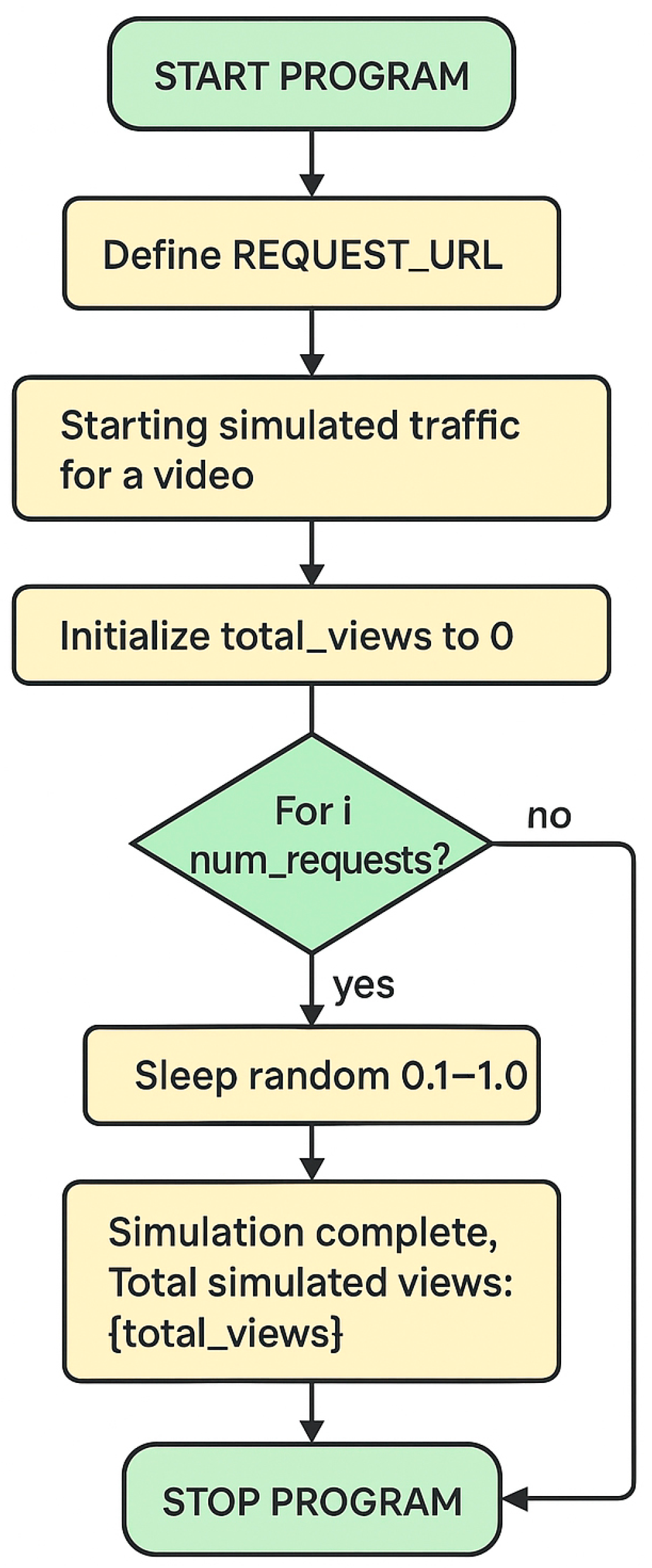

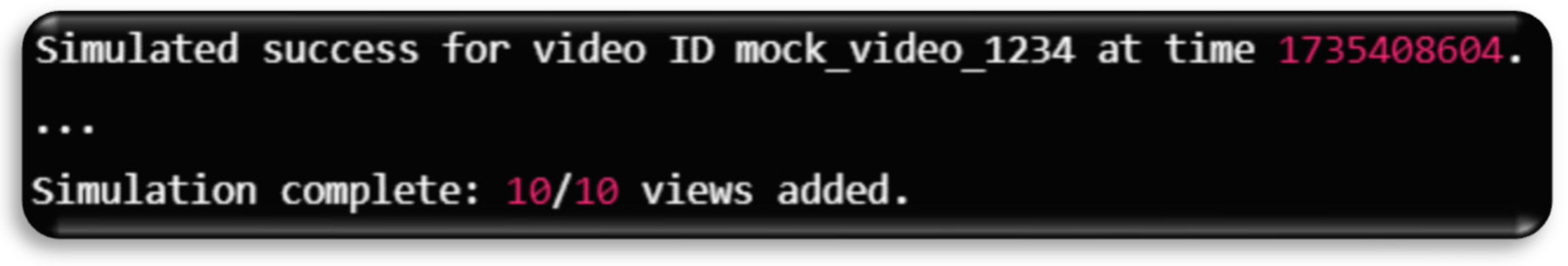

Figure 7 illustrates the use of a Python script to simulate multiple requests to a server, demonstrating how fictitious traffic and automated views can be generated on TikTok, thus highlighting the reasons for the popularity of content related to the independent candidate. This type of experiment can be extended to a controlled environment, so as not to violate ethical rules. Such a script creates “fictitious” requests to understand the principles of traffic generation. In this case, the requests do not interact with a real server, introduce delays to simulate realistic user behavior, and display the progress and total number of simulated requests. This script simulates fictitious interactions with a server to understand how traffic is generated in a controlled environment and to avoid violating the platforms’ terms of use. The script creates a loop that runs a specified number of times. For each iteration, the script emulates a request for the specified video, introduces a random delay between requests to simulate human interactions (0.1–1 s), and updates and displays the progress, indicating how many “views” have been simulated up to that point. Finally, the script performs the simulation, displaying the total number of requests sent for the specified video. According to previous presentations, we are talking about a basic input through which imports are set regarding the created accounts, and how the Video ID (the unique identifier of the video) is taken to specify for which content the traffic is simulated.

Figure 7 illustrates the high-level control flow of a prototype simulation utility used to study the effects of bursty, concurrent request patterns against a video resource. The diagram shows the principal stages: initialization of configuration parameters (target resource identifier and total request count), entry into the simulation routine, iterative generation of request events, local pacing between events, and termination reporting. The logical structure follows a common producer/worker pattern: a top-level controller establishes experiment parameters, while multiple worker activities execute request events and update shared counters under synchronization. The algorithm accepts two primary inputs, a resource identifier and a nominal request count, and orchestrates a loop that generates the requested number of events. To emulate simultaneous load, the design commonly uses concurrency primitives (e.g., threads or worker pools) together with mutual-exclusion constructs to protect shared state (such as the global view counter). Inter-event delays and randomized pacing are incorporated to produce non-uniform arrival patterns. A monitoring/aggregation step collects per-worker success/failure statistics and prints a summary on completion.

In the design and evaluation of simulated traffic algorithms, several technical and ethical considerations must be addressed to ensure responsible and reproducible experimentation. First, rate control and pacing mechanisms are essential to respect platform-imposed limits and prevent unintended service degradation; excessive burst requests can activate automated protection systems such as throttling or blocking. Concurrent execution using multi-threaded or worker-based models can enhance throughput but must employ robust synchronization primitives—such as locks or atomic counters—to avoid race conditions and maintain data integrity. Equally important is comprehensive error handling and telemetry collection, including detailed logging of success and failure rates, latency distributions, and response classifications, which enable deeper diagnostics and reproducibility of results. For larger-scale simulations, experiments should only be conducted on controlled testbeds or authorized environments, as redirecting traffic through third-party hosting or proxy networks without consent constitutes both a technical and legal violation. From an ethical and compliance perspective, all traffic simulations should be performed within a defined research framework that includes documented objectives, prior authorization from the platform owner, and safeguards to prevent spillover effects. To ensure methodological transparency, reports should include metadata such as the number of simulated requests, concurrency model, pacing policy, observed performance metrics, and a clear statement that all tests were conducted on isolated or sanctioned environments (

Nisa et al., 2021).

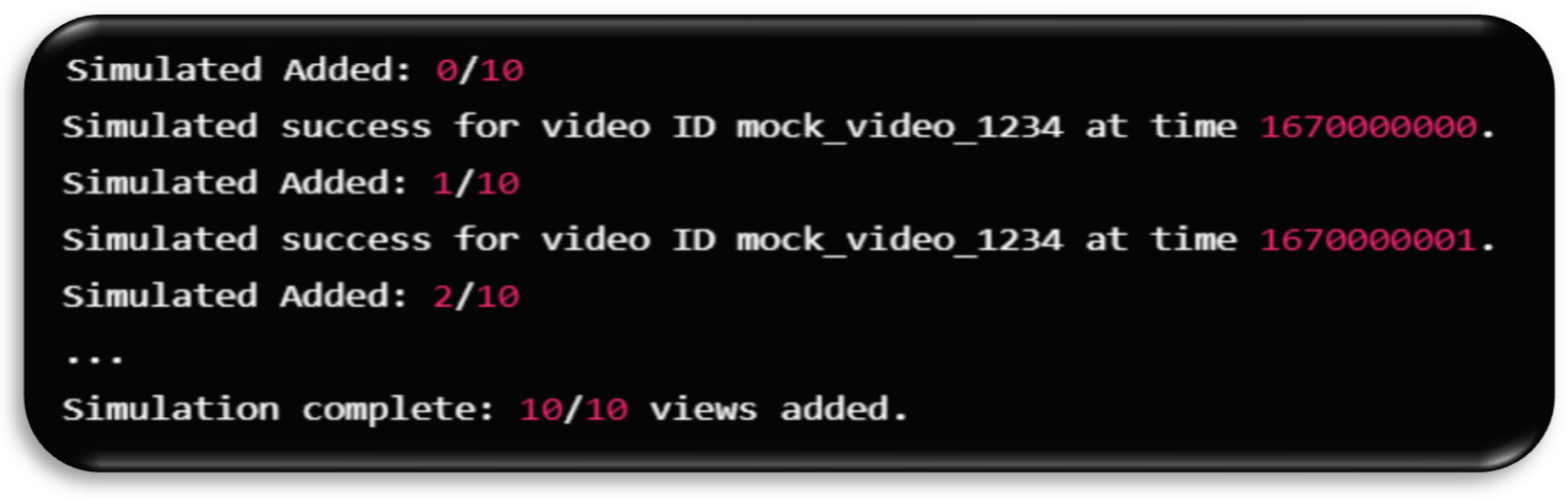

Therefore, we can specify the number of views to simulate (amount) and then the TikTok video ID (video_id), and then many threads are created to simulate simultaneous requests, emulating increased traffic. The lock mechanism is used to protect critical sections to achieve simultaneous views. In a word, the script sends simulated requests, that exceed 95% success rate, and the result of the internal tests performed, which are demonstrative, are used only for educational purposes and to validate the method used in the electoral campaign. However, there are different versions of scripts already created by software developer communities in which it is observed that they can also redirect traffic, comments, and reactions and can very easily mislead the user. The output of the demonstration script could look like this when run, and see the

Figure 8.

The script successfully generates views for a fictitious video called (mock_video_1234), each iteration being successfully recorded with a timestamp, with each view added, the script notifies the progress status, see the

Figure 9.

This comparison illustrates that artificially boosted content achieved significantly higher reach, but at the expense of authentic engagement. The findings highlight the dual effect of algorithmic manipulation: increased visibility alongside diluted audience interaction.

To illustrate the impact, comparative values were drawn from test scenarios and secondary reports: average views for organic videos reached ~3000 within 24 h, while artificially boosted videos exceeded 15,000 views in the same interval. However, the engagement ratio (likes/comments per 1000 views) dropped by over 60%, highlighting that amplification mainly inflates visibility without generating proportional interaction, see the

Table 2.

These indicative figures support the claim that social media algorithms, when manipulated, can distort perceived popularity and thereby influence voter behavior. The result of this process is that within 12–24 h, the video material can reach over 1 million views, and this number can influence the real users of the platform in making certain decisions, especially since we are talking about the use of such a tool in manipulating the masses. If we are talking about any content that does not bring information through which to influence certain legislative, governmental, and integrity aspects, we can overlook the speculation of the vulnerabilities of any platform. This time, we are talking about a well-defined architecture, multiple videos that respect a pattern and are based on a set of information that reaches the sensitive side of the users, and keywords that identify the campaign carried out, but more than that, tags that the videos must have are required, these making a direct link with all the videos that the candidate exposes. When a thousand videos in the description contain a viral tag, it is ranked in that platform and can even generate links between content in the same category. Therefore, we can say that in addition to the virtual help generated by the platform, scripting, and programming techniques, the human factor and socio-emotional analysis, direct analysis of discourse, formulation, and expression played an extremely important role in penetrating the target audience. We can say that a favorable environment was created through several techniques, marketing, branding, BigData, programming, neurolinguistic analysis, and mass psychology, but also a discourse that refers to the voice of the people, which has not been listened to at all in the last 35 years, leading to this surprise of the presidential elections in Romania.

3.3. Exposing the NLP Analysis Model and Exposing the Impact Generated by Discourse Analysis Using Advanced Algorithms

Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques were applied to examine the textual content extracted from TikTok videos, captions, and related online media sources. The goal of this analysis is to identify recurring linguistic patterns, sentiment polarity, and emotional framing associated with the 2024 Romanian presidential election discourse. The speech represents a complex construction, intended, in the case of candidates, to combine a series of themes, which would emotionally mobilize large segments of the electorate. In the case of the independent candidate, who surprised many people by advancing to the second round of the presidential elections, he raised historical, religious, and nationalist themes, using communication techniques based on emotion, in a context of deep social and political dissatisfaction. In the November 2024 elections, voters cast a vote against the traditional parties, PSD and PNL, which have been viewed by the population in recent years as being disconnected from the needs of the population. Also, the mandate of the current president of Romania has been sprinkled with dissatisfaction, thus creating fertile ground for populist speeches. Given that Romania has one of the highest inflation rates in the European Union, rising prices and poverty have amplified the population’s frustration, making it vulnerable to a discourse that acts like a dressing, offering simplified answers to complex problems. At the same time, the discourse built on the idealization of a glorious past, of “Greater Romania” and traditional values, with references to the “peasant household” and self-sufficiency, resonates with nostalgic segments of the population, but also with young people between 18 and 35 years old, who did not live through the times of communism, but perceive them as more stable, based on family or media narratives. The family is an integral part of the discourse, being considered the “backbone of society”, and references to faith and God were not slow to appear, building the relationship with voters effectively, based on trust.

Political parties and economic interests were also other keywords used in the speech of the independent candidate, who frequently criticized NATO or the EU, although he stated that he did not want Romania to leave these structures. In this context, NLP techniques and hypnotic rhetoric are used, through the repetition of the terms “people”, “peace”, “dignity” and “faith”, which were used to create strong mental associations with the values promoted. Regarding the pace of the speech, it is slow, with a series of very well-placed pauses, giving it a solemn and authoritative air. Therefore, the speech of the independent candidate resonated with disappointed, vulnerable, or marginalized voters. His figure offered them hope and meaning in a complex and difficult socio-political context. In this context, the graphic representation, made in Word Cloud below, has the role of highlighting the main keywords used in the language of the independent candidate. In the use of NLP, especially in terms of the text preprocessing process, tokenization is necessary, which involves fragmenting the text into smaller units, called tokens, which can be represented by words or linguistic segments, with the role of facilitating the labeling of parts of speech, as well as the analysis of subsequent sentiments. Regarding the independent candidate, keywords such as “people”, “sovereignty” or “family” are isolated to analyze their use in depth. Discourse analysis involves a series of logical relationships between sentences, designed to ensure textual coherence, by identifying semantic and syntactic connections between sentences. At the sign level, the emphasis is on understanding the literal meaning of words, and terms such as “peace” or “dignity” are transposed to convey emotional messages.

Figure 11 shows the main keywords used by the independent candidate in his speech, who entered the 2nd round of the presidential elections.

This WordCloud represents the most frequent lexical elements extracted from the public TikTok statements of Calin Georgescu, the independent presidential candidate. The dataset includes all verbal content (spoken or captioned) from TikTok videos published on his public profile during the final 14 days of the campaign.

- ✓

The text corpus was compiled through manual transcription and collection of visible captions and audio content.

- ✓

Standard Natural Language Processing (NLP) preprocessing was applied: stop words were removed, terms were lemmatized, and tokens were filtered for relevance.

- ✓

The size of each word in the cloud reflects its frequency of appearance across all collected videos.

- ✓

Color variation and font style have no analytical meaning and were applied automatically by the WordCloud rendering algorithm for readability and aesthetic diversity.

In the case of discourse, pragmatics uses real-world knowledge to complete textual meanings but can encounter difficulties in the case of contextual ambiguity, where interpretations vary depending on the reader’s experiences. In NLP, ambiguity is a real challenge, appearing at syntactic, semantic, and lexical levels. Also, detecting tone and themes involves identifying dominant topics, such as patriotism, faith, or independence, and evaluating the attitude expressed. Perhaps the most pervasive message he exposed in his campaigns and as a direct reproach to the political class was the following: “Do not feel the cold and hunger that this people endure.” The independent candidate frequently uses terms that evoke national unity and traditional values, such as “people” and “Romania.” Criticisms of politicians and electoral campaigns suggest an anti-establishment stance, designed to appeal to voters dissatisfied with the current political situation. References to “education” and “health” indicate priorities in his program, addressing pressing social issues.

As for the analysis of the statements of the surprise candidate, it was carried out through NLP procedures, by studying the frequency and tone of the words used in his statements, the algorithm being realized in Python. This method helps to identify linguistic patterns, sentiments, and key points in a complex text. The purpose of preprocessing is to prepare the raw content for analysis and removing noises, preserving relevant elements, converting to lowercase for non-influential, and this is conducted by converting to lowercase.lower() format for uniformity. Removal of special characters and regular expressions is performed so as not to influence semantics or punctuation, based on the re.sub function, text.lower(), then the text is split into individual words using the.split() method. We remove common and irrelevant words like “and”, “of”, and “the” from the text. The list of these words is called stop words. We use the collections Counter library to count the frequency of each word. This allows us to see which words are used most often.

When we talk about analyzing the sentiment of the speaker, we also need to evaluate the tonality of the text and establish the tonality classes, which are as follows:

- ✓

Positive (e.g., “prosperity”, “freedom”),

- ✓

Negative (e.g., “corruption”, “bankruptcy”),

- ✓

Neutral (the rest of the words that do not fit into the previous categories).

For this, we use two predefined lists:

positive_words and

negative_words. We count the words in each category and determine the proportion of each type of sentiment. To perform the presented analysis, we extract a raw text, and in this case, we are discussing 3915 words, which are passages from the candidate’s statements, then we remove the stop words and count the frequency of relevant words with that counter. Each word is validated and checked against the positivity or negativity lists, recording the number of words falling into a certain category. Sentiment analysis, based on predefined sets of positive and negative keywords, quantified the emotional tone of the text. The results showed a pre-dominantly neutral sentiment, with notable peaks in both positive (e.g., “prosperity”, “hope”) and negative (e.g., “corruption”, “injustice”) expressions. This duality reflects the balanced nature of political discourse, which often combines aspirations for improvement with criticism of existing systems. Visual representations, including bar charts of word frequency and sentiment distributions, improved the interpretability of the findings, allowing for a deeper exploration of the textual data. Graphical results confirmed the prominence of key ideological themes and provided a clear overview of sentiment dynamics. This analysis demonstrates the effectiveness of NLP in extracting semantic insights from political texts, providing a scalable and reproducible methodology for studying narrative structures, thematic underlining, and emotional underlining in public communications. Such approaches can be essential in comparative analyses of political rhetoric, tracking sentiment over time, and identifying changes in ideological focalization.

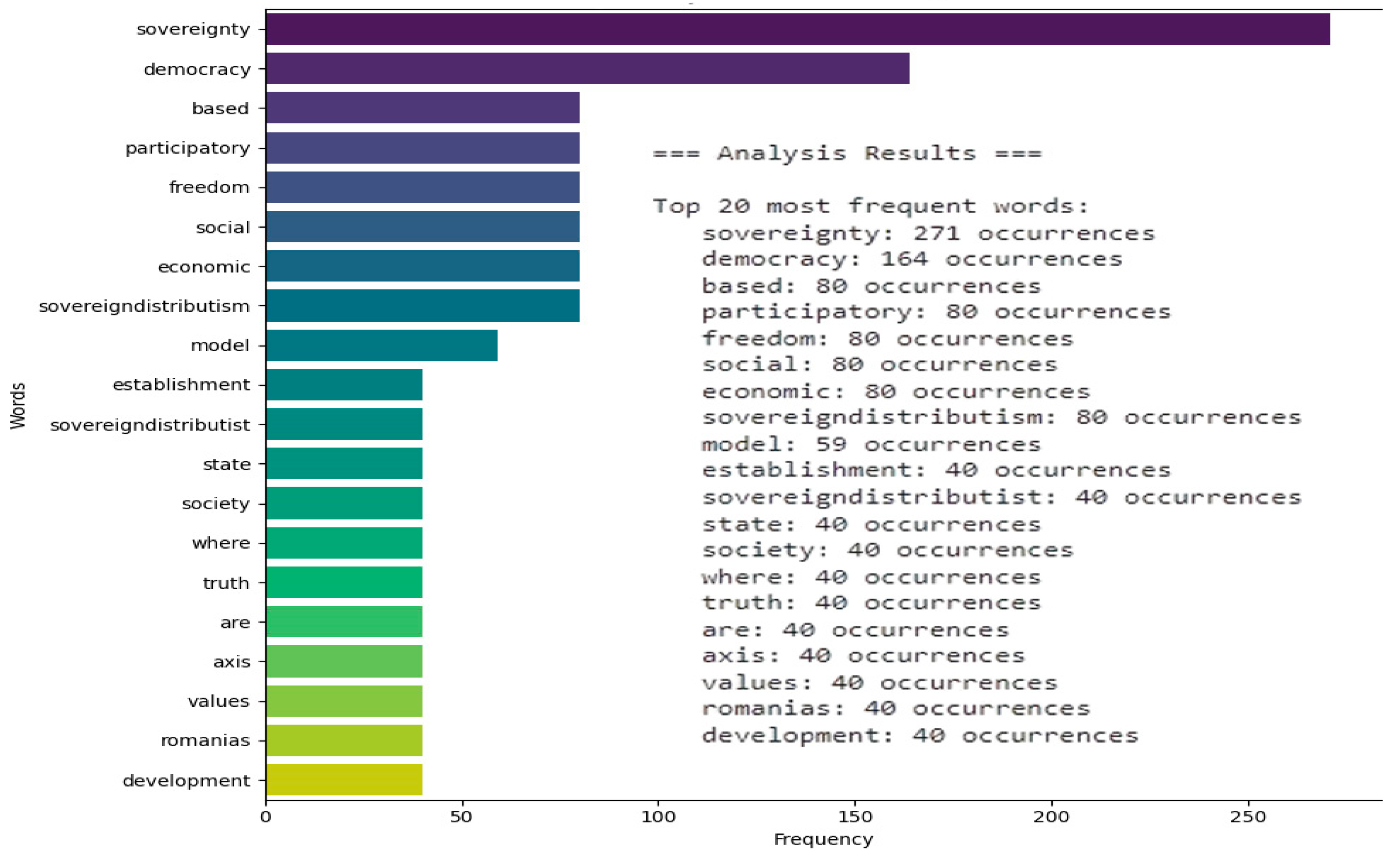

Figure 12 represents the frequency distribution of the 20 most frequently used words in the textual data analyzed.

The analysis focuses on identifying the dominant linguistic elements that shape the ideological framing of the candidate’s discourse. The problem addressed here concerns the way key political concepts are repeatedly employed to reinforce specific values and collective narratives. The dataset used for this analysis consists of textual material extracted from TikTok transcriptions and online press articles, processed through NLP-based frequency and clustering tools. Using these computational methods, the distribution and recurrence of lexical items were measured to reveal semantic patterns across the discourse. The bar chart shows that terms such as ‘sovereignty’ (271 occurrences) and ‘democracy’ (164 occurrences) dominate the discourse, emphasizing an ideological focus on national sovereignty and participatory governance. Words such as ‘freedom’, ‘social’, ‘economic’, and ‘participatory’ (each with approximately 80 occurrences) further highlight themes of societal well-being and inclusive political systems. The frequent appearance of expressions such as ‘sovereign distributism’ and ‘truth’ reflects the candidate’s emphasis on a proposed socio-economic model grounded in moral and ethical principles. Overall, the lexical distribution demonstrates a strong alignment with the overarching themes of governance, identity, and development, clearly articulating the priorities embedded in the political message.

From this analysis, it can be deduced that the candidate’s text was strategically constructed to appeal to the values, needs, and aspirations of the Romanian electorate. The repetitive use of terms such as ‘sovereignty’, ‘democracy’, ‘freedom’, and ‘participatory’ suggests a deliberate rhetorical strategy aimed at psychological resonance with the target audience. These linguistic choices are not coincidental but instead reflect ideals deeply rooted in Romania’s social and cultural consciousness. The discourse was thus structured empirically, based on an understanding of collective psychology, to convey messages that respond simultaneously to social issues and to the population’s aspirations (

Tajfel et al., 1971).

The figure shows the frequency of the 20 most used words in the public speech of candidate Călin Georgescu. The data comes from a combination of:

- (1)

Manual transcriptions of videos posted on TikTok during the campaign (made through social listening);

- (2)

Statements taken from press articles, interviews, and publications directly associated with the candidate.

The lexical analysis was performed using an automatic processing script (tokenization, lemmatization, and raw frequency), and the result highlights the dominant vocabulary with political, sovereignist, economic, and social connotations.

Detailed methodology (Materials and Methods):

N = 100 text and video materials, period: 14 pre-electoral days;

Video source: candidate’s official TikTok account + thematic redistributions;

Textual source: national newspapers (e.g., Adevărul, Mediafax), TV appearances and documented statements;

Processing: Python 3.13.2. + spaCy, in analysis window τ = 24 h.

The repetition of key terms, such as “sovereignty” and “democracy,” suggests a strategy to strengthen public confidence in national values and participatory democracy. This approach seems to have been designed to reach all social classes, from the intelligentsia to the most vulnerable communities, using common, simple but powerful language linking ideas of freedom, prosperity, and control over one’s own identity. On the other hand, word choice also conveys a communication strategy based on repetition—one of the most effective methods of reinforcing messages in social psychology. This repetitiveness serves to create a “mental anchor,” through which people identify with the candidate’s vision of society.

A combination of empathy, an understanding of social needs, and an emphasis on key ideas was used to help the messages penetrate more easily into the layers of society. Thus, the candidate addressed “in the language of Romanians,” not only linguistically, but also culturally, managing to construct a discourse that reflected what the audience wanted to hear, promoting a rhetoric of sovereignty, traditional values, and hope for a better future.

Figure 13 provides an analysis of sentiment within the candidate’s statements, segmenting the text into three categories of sentiment: positive, neutral, and negative. From the graph, we observe an overwhelming prevalence of neutral sentiments (2265), followed by positive (391), while negative sentiments are absent. This distribution reflects a discursive strategy aimed at maintaining a balanced tone and avoiding polarization. Neutral sentiments indicate descriptive and factual language, aimed at providing information and communicating ideas without generating conflict or strong emotions.

Therefore, the presence of a considerable number of positive sentiments denotes an attempt to inspire optimism, hope, and confidence in the public by emphasizing concepts such as “prosperity,” “democracy” and “freedom.” The absence of negative sentiments indicates that the discourse avoided confrontational rhetoric, focusing instead on a constructive message tailored to the needs and aspirations of the population. This analysis highlights a strategic approach in which neutral language serves as a foundation for clarity and coherence, while positive components are used to solidify key messages and mobilize the emotional support of the audience. A limitation of this analysis is the relatively small size of the textual corpus (3915 words), which constrains the statistical robustness of NLP-based findings. Nevertheless, the analysis highlights discursive patterns and strategies relevant for understanding the candidate’s rise. Future research will expand the dataset by incorporating transcripts of debates, media appearances, and social media posts, in order to strengthen the statistical validity of results.

The figure reflects the visualization of the frequency of the most recurrent words, extracted from a corpus of texts consisting of TikTok posts and press quotes associated with the candidate. The method does not automatically distinguish between positive/negative affective tone, but only the relevance of lexical recurrence. Polarity analysis is discussed in a separate section. The assessment of negative tone (e.g., labeling, attacks) was subsequently performed using polarity analysis (lexicon + NLP scores), presented in an additional subchapter.

Figure 13 presents only the raw frequency of the most recurrent lexemes, not their affective filter.

The absence of explicitly negative words in the analyzed campaign speech is not a methodological omission, but rather a reflection of the candidate’s deliberate rhetorical strategy. As an independent challenger with strong appeal in Romania’s North-Eastern region, a demographically religious and culturally conservative area, the candidate adopted a calm, spiritually infused tone throughout his public discourse. His rhetoric emphasized unity, prosperity, moral values, and national identity rather than antagonistic or confrontational language.

This discursive style is aligned with the expectations and beliefs of his primary audience, which comprises largely faith-oriented voters. The sentiment analysis reveals a predominance of neutral and positive wording, consistent with his pious and value-driven messaging. It is important to underscore that political rhetoric rooted in spiritual or transcendent framing can purposefully avoid negativity in order to maintain moral authority and emotional connection with the electorate.

Furthermore, the correlation between speech tone and voter geography is also supported by official data (e.g., RoAEP results), where the highest support was registered in the North-Eastern counties, regions historically more inclined toward religious and traditional narratives. This phenomenon should not be seen as a deviation from campaign norms, but rather as a culturally and electorally contextualized rhetorical strategy, which is both valid and theoretically documented in the field of political discourse analysis.

Figure 14 illustrates the geographical distribution of the majority votes across Romanian counties in the 2024 presidential election. It highlights a strong concentration of support for the independent candidate Călin Georgescu (marked in green) in the North-East and central–northern regions of the country, with notably high percentages in counties such as Neamț (68.44%), Botoșani (33.74%), and Bistrița-Năsăud (30.61%).

This regional pattern reinforces the broader analytical point made in relation to

Figure 13: Georgescu’s campaign was anchored in a spiritual and traditionalist discourse that resonated deeply with culturally conservative and religious communities. These regions, historically shaped by strong Orthodox Christian traditions and cohesive local networks, provided fertile ground for value-based, non-confrontational messaging centered on sovereignty, faith, dignity, prosperity, and moral integrity.

However, it is important to note that the visibility of conservative and religious narratives on TikTok does not necessarily imply that these demographic groups are directly active on the platform. Rather, such discourse was often amplified indirectly, through younger sympathizers, influencers, and algorithmic recommendation systems that favor emotionally charged or symbolic content. In contrast, the southern and western regions leaned more toward systemic candidates, reflecting differing economic priorities, media exposure, and ideological orientations. The spatial polarization observed here also mirrors digital engagement patterns, where Georgescu’s narrative achieved substantial virality in the green-marked counties. Overall, this map, when cross-referenced with sentiment and keyword analyses, supports the hypothesis that identity-driven and emotionally resonant discourse can act as a strategic mobilization vector in digitally mediated electoral campaigns, even when propagated indirectly across audience boundaries.