Employee Objectification in Modern Organizations: Who Has Swept Personal Dignity Under the Carpet?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

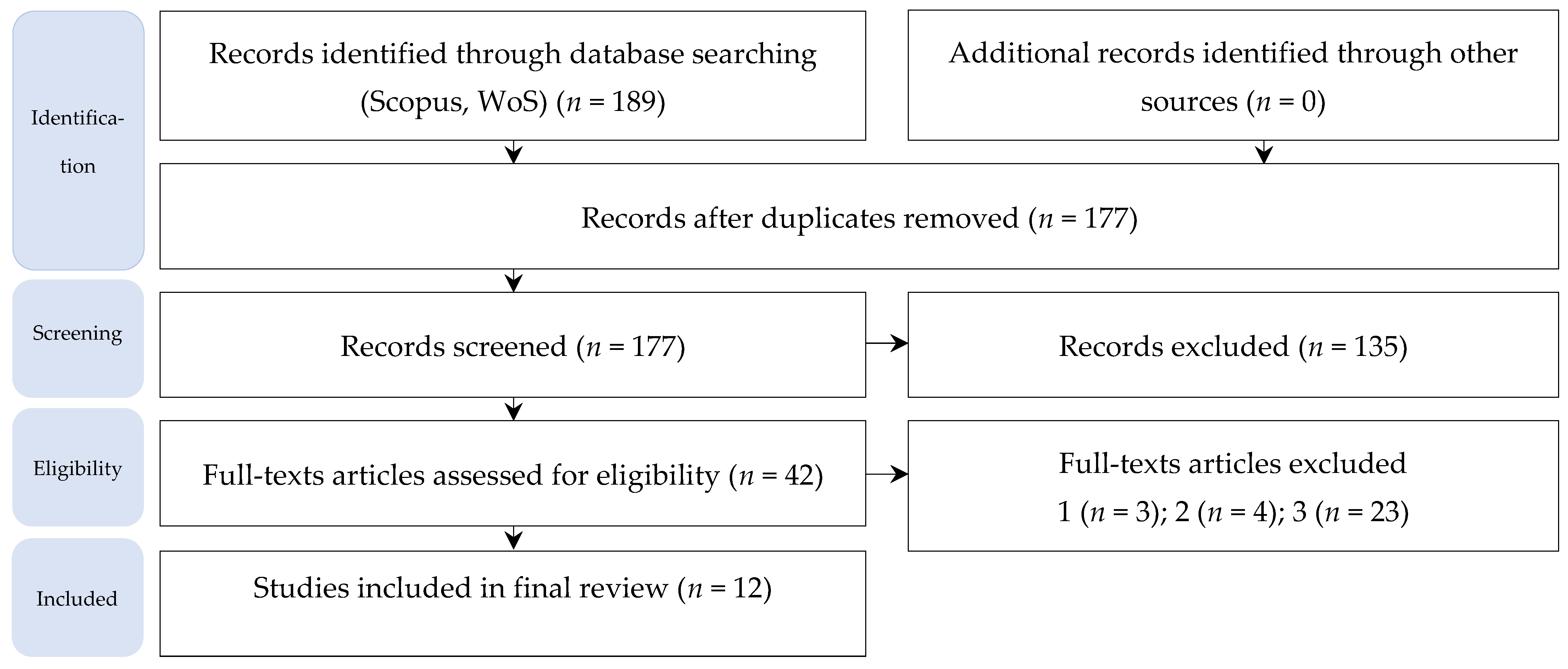

3. Methodology

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, A., Liang, D., Anjum, M. A., & Durrani, D. K. (2023). Does dignity matter? The effects of workplace dignity on organization-based self-esteem and discretionary work effort. Current Psychology, 42(6), 4732–4743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrighetto, L., Baldissarri, C., & Volpato, C. (2017). (Still) modern times: Objectification at work. European Journal of Social Psychology, 47(1), 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auzoult, L. (2021). Can meaning at work guard against the consequences of objectification? Psychological Reports, 123(3), 872–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldissarri, C., Andrighetto, L., & Volpato, C. (2022). The longstanding view of workers as objects: Antecedents and consequences of working objectification. European Review of Social Psychology, 33(1), 81–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmi, P., & Schroeder, J. (2021). Human “resources”? Objectification at work. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 120(2), 384–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohns, V. K., & Flynn, F. J. (2013). Underestimating our influence over others at work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 33, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bolton, S. C. (2010). Being human: Dignity of labor as the foundation for the spirit–work connection. Journal of Management, Spirituality and Religion, 7(2), 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury-Jones, C., Aveyard, H., Herber, O. R., Isham, L., Taylor, J., & O’malley, L. (2022). Scoping reviews: The PAGER framework for improving the quality of reporting. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 25(4), 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesens, G., Nguyen, N., & Stinglhamber, F. (2019). Abusive supervision and organizational dehumanization. Journal of Business and Psychology, 34(5), 709–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, F., Tricco, A. C., Munn, Z., Pollock, D., Saran, A., Sutton, A., White, H., & Khalil, H. (2023). Mapping reviews, scoping reviews, and evidence and gap maps (EGMs): The same but different—The “Big Picture” review family. Systematic Reviews, 12, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, K., & Ellinger, A. E. (2019). An evaluation of Web of Science, Scopus and Google Scholar citations in operations management. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 30(4), 1039–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J., Shim, S. H., & Kim, S. (2023). The power of emojis: The impact of a leader’s use of positive emojis on members’ creativity during computer-mediated communications. PLoS ONE, 18(5), e0285368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y., Jiang, T., Gaer, W., & Poon, K.-T. (2023). Workplace objectification leads to self-harm: The mediating effect of depressive moods. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 51, 1219–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Reis, R. J., Machado, M. M., Gati, H. H., & Falk, J. A. (2021). Perception of deaf people on dignity in organizations. In M. L. Mendes Teixeira, & L. M. B. d. Oliveira (Eds.), Organizational dignity and evidence-based management (pp. 105–119). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer-Daly, M. M. (2022). Dignity and bargaining power: Insights from struggles in strawberries. Industrial Relations Journal, 53(3), 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T.-A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C., Thomason, B., Margolis, J., Groves, K., Gibson, S., & Franczak, J. (2023). Dignity inherent and earned: The experience of dignity at work. Academy of Management Annals, 17(1), 218–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granulo, A., Caprioli, S., Fuchs, C., & Puntoni, S. (2024). Deployment of algorithms in management tasks reduces prosocial motivation. Computers in Human Behavior, 152, 108094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamel, J.-F., Villieux, A., Montalan, B., & Scrima, F. (2024). Tools are not meant to flourish. The mediating role of self-objectification between organizational dehumanization and psychological flourishing at work [Un outil n’est pas fait pour s’épanouir. Le rôle médiateur de l’auto-objectification entre la déshumanisation organisationnelle et l’épanouissement psychologique au travail]. Psychologie du Travail et des Organisations, 30, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harder, B. D., Harinck, F. I. E. K. E., Van Der Doef, M. A. R. G. O. T., Van Der Toorn, J. M., & Gebhardt, W. A. (2023). Current knowledge on organizational humanness and its relation to leadership: A scoping review. TPM-Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology, 30(2), 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S. R. (2023). (Not) Paying for diversity: Repugnant market concerns associated with transactional approaches to diversity recruitment. Administrative Science Quarterly, 68(3), 824–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, I. (2020). Groundwork of the metaphysic of morals (pp. 17–98). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Khademi, M., Mohammadi, E., & Vanaki, Z. (2012). Nurses’ experiences of violation of their dignity. Nursing Ethics, 19(3), 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieser, A., Nicolai, A., & Seidl, D. (2015). The practical relevance of management research: Turning the debate on relevance into a rigorous scientific research program. Academy of Management Annals, 9(1), 143–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langton, R. (2009). Sexual solipsism: Philosophical Essays on pornography and objectification. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Latemore, G., Steane, P., & Kramar, R. (2020). From Utility to Dignity: Humanism in Human Resource Management. In R. Aguado, & A. Eizaguirre (Eds.), Virtuous cycles in humanistic management. Contributions to management science. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmon, G., Jensen, J. M., & Kuljanin, G. (2022). A primer with purpose: Research implications of the objectification of weight in the workplace. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 95(2), 550–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. (2016). Beauties at Work: Sexual Politics in a Chinese Professional Organization. Nan Nü, 18(2), 326–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Cortes, O. D., Betancourt-Núñez, A., Orozco, M. F. B., & Vizmanos, B. (2022). Scoping reviews: A new way of evidence synthesis [Scoping reviews: Una nueva forma de síntesis de la evidencia]. Investigacion en Educacion Medica, 11(44), 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughnan, S., Baldissarri, C., Spaccatini, F., & Elder, L. (2017). Internalizing objectification: Objectified individuals see themselves as less warm, competent, moral, and human. British Journal of Social Psychology, 56(2), 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, K. (2015). Workplace dignity: Communicating inherent, earned, and remediated dignity. Journal of Management Studies, 52(5), 621–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, K., Manikas, A. S., Mattingly, E. S., & Crider, C. J. (2017). Engaging and Misbehaving: How Dignity Affects Employee Work Behaviors. Organization Studies, 38(11), 1505–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardosas, E., Vveinhardt, J., & Davidavičius, A. (2021). Reification in market societies: Theoretical conceptualizations and researchability. Filosofija. Sociologija, 32(1), 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marková, I. (2012). Objectification in common sense thinking. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 19(3), 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, W. (2011). Organizational contexts for environmental construction and objectification activity. Journal of Management Studies, 48(4), 804–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertz, B. A., Locander, J. A., Brown, B. W., & Locander, W. B. (2024). Dignity in the workplace: A frontline service employee perspective. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 32, 506–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, C., Nayebare, A., Neema, S., Agaba, A., & Akello, L. P. (2021). Uganda’s response to sexual harassment in the public health sector: From “Dying Silently” to gender-transformational HRH policy. Human Resources for Health, 19(1), 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, M. C. (1995). Objectification. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 24, 249–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadaki, L. (2010). What is objectification? Journal of Moral Philosophy, 7(1), 16–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M. D., Marnie, C., Colquhoun, H., Garritty, C. M., Hempel, S., Horsley, T., Langlois, E. V., Lillie, E., O’Brien, K. K., Tunçalp, Ö., Wilson, M. G., Zarin, W., & Tricco, A. C. (2021). Scoping reviews: Reinforcing and advancing the methodology and application. Systematic Reviews, 10(1), 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C. M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., & Soares, C. B. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13(3), 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, M. T., Rajić, A., Greig, J. D., Sargeant, J. M., Papadopoulos, A., & McEwen, S. A. (2014). A scoping review of scoping reviews: Advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Research Synthesis Methods, 5(4), 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirson, M. (2017). Humanistic management: Protecting dignity and promoting well-being. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock, D., Peters, M. D., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Alexander, L., Tricco, A. C., Evans, C., de Moraes, É. B., Godfrey, C. M., Pieper, D., Saran, A., Stern, C., & Munn, Z. (2023). Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 21(3), 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainz, M., Moreno-Bella, E., & Torres-Vega, L. C. (2023). Perceived unequal and unfair workplaces trigger lower job satisfaction and lower workers’ dignity via organizational dehumanization and workers’ self-objectification. European Journal of Social Psychology, 53(5), 921–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, J., & Grant, D. (2010). Psychologising the subject: HRM, commodification, and the objectification of labour. The Economic and Labour Relations Review, 20(2), 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, M. L. M., das Graças Torres Paz, M., & Alves, S. S. (2021). Dignity and Well-Being at Work. In M. L. Mendes Teixeira, & L. M. B. d. Oliveira (Eds.), Organizational dignity and evidence-based management (pp. 271–281). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valtorta, R. R., & Monaci, M. G. (2023). When workers feel like objects: A field study on self-objectification and affective organizational commitment. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 19(1), 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, J. J. (2004). Human dignity and the objectification of the human being. Analecta Husserliana, 79, 537–602. [Google Scholar]

- Vveinhardt, J. (2022). The dilemma of postmodern business ethics: Employee reification in a perspective of preserving human dignity. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 813255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vveinhardt, J., & Deikus, M. (2023). Strategies for a nonviolent response to perpetrator actions: What can christianity offer to targets of workplace mobbing? Scientia et Fides (SetF), 11(2), 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vveinhardt, J., & Deikus, M. (2025). Synderesis vs. consequentialism and utilitarianism in workplace bullying prevention. Social Inclusion, 13, 8406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphaln, K. K., Regoeczi, W., Masotya, M., Vazquez-Westphaln, B., Lounsbury, K., McDavid, L., Lee, H., Johnson, J., & Ronis, S. D. (2021). From Arksey and O’Malley and Beyond: Customizations to enhance a team-based, mixed approach to scoping review methodology. MethodsX, 8, 101375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L., Fan, A. A., & Mattila, A. S. (2015). Wearable technology in service delivery processes: The gender-moderated technology objectification effect. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 51, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X., Wang, Y., Li, M., & Kwan, H. K. (2021). Paradoxical effects of performance pressure on employees’ in-role behaviors: An approach/avoidance model. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 744404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B., Wisse, B., & Lord, R. G. (2023). How objectifiers are granted power in the workplace. European Journal of Social Psychology, 53(4), 681–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor | Features | Mechanism | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Work Structure | Work distinguishing itself by repetition of activities, fragmentary nature, and dependence on technological systems, where the employee performs strictly defined tasks without personal control | Such structure directs the observer’s attention to actions rather than to the person as a whole, which is why the employee is perceived as a means. | Andrighetto et al. (2017) |

| Status | Employees occupying lower-status positions are more often perceived through the instrumental prism, as persons performing mechanical tasks requiring obedience. | Low social or organizational status activates stereotypical expectations, due to which the person is considered less competent, with low agency, and less deserving individual attention. | Valtorta and Monaci (2023); Loughnan et al. (2017) |

| Organizational culture | The emphasis is placed on productivity, profit, and seeking goals at the expense of employees. In such organizations, workers are more likely to be viewed as resources rather than as people. | Goal orientation encourages to assess employees according to their instrumental value, perception of unique human traits, features or intentions is weakening, and attention is focused only on their functions. | Belmi and Schroeder (2021) |

| Uncertainty | Uncertainty arising from both environmental instability, change, and loss of control. | Acts as a defensive reaction that encourages ignoring human qualities. | Baldissarri et al. (2022); McKinley (2011) |

| Author | Aim | Findings | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Bohns & Flynn, 2013) | To answer the question whether people are aware of the influence they have over others in the workplace | People who tend to objectify others, undervalue their intentionality, and overestimate their own influence. | Encourage managers and employees to consider the perspectives of individuals within their sphere of influence and seek ways to reduce anxiety. |

| (Xu et al., 2021) | To explore the double sides of performance pressure. | Pressure for results can activate the sense of self-objectification and encourage one to become more involved in one’s roles. | To ensure the constructive interpretation, communication, and feedback of employees, managers must weaken their employees’ tendencies to avoid challenges and reduce their anxiousness. |

| (Newman et al., 2021) | To identify the nature, contributors, dynamics, and consequences of sexual harassment in public health sector workplaces and assess these in relation to available theories. | Unwanted sexual attention, including non-consensual touching, bullying and objectification, was related to greater anxiety and distress. | Leaders should seek solutions to end gender-based harassment and make gender equality a human resources priority in health policy. |

| (Lemmon et al., 2022) | To describe the process by which intraculturally determined body size preferences impact how observers think about and react to larger-bodied colleagues, and how these larger-bodied colleagues internalize and cope with these judgements. | The motivation for the objectification of people with large builds stems from broader Western cultural approaches to occupational health. | Educational programming and teaching to talk about many ways of implementing ‘health’. |

| (Liu, 2016) | To illuminate the importance of a local socio-cultural context in shaping the contour of sexualized control and resistance. | Women are controlled through the process of objectification, which reinforces vertical gender segregation. | |

| (Choi et al., 2023) | To examine the impacts of a leader’s use of positive emojis on members’ creativity. | The use of positive emotions reduces employees’ perception that the manager is objectifying them. | To encourage creativity, managers can actively provide positive attention and support to employees by incorporating positive emoticons into computer-mediated communication with them. |

| (Granulo et al., 2024) | To investigate how deploying algorithms in management tasks affects prosocial motivation, a crucial dimension of workplace productivity and social interactions. | Management using artificial intelligence algorithms leads to greater objectification of others. | To treat employees not only as passive recipients but also as active participants in corporate decision-making processes related to algorithmic management practices. |

| (Jackson, 2023) | To examine how a technology firm, ShopCo (a pseudonym), considered 13 different recruitment platforms to attract racial minority engineering candidates. | Hiring that is oriented to transactions (effectiveness, quantity, and reward), unlike hiring oriented to development (communality, opportunities, and ethics), is associated with employee objectification. | |

| (Zhang et al., 2023) | To examine whether subordinate power distance orientation, as an individual level construct, moderates the extent to which supervisor objectification is justified, and, furthermore, the extent to which objectifying supervisors are afforded power. | In high power distance organizations, subordinates give more power to the manager who objectifies them, because such behaviour is perceived as appropriate. | It is proposed to create a culture of low power distance, to respect individual life. |

| (Harder et al., 2023) | To provide an overview of the available body of knowledge on organizational humanness and its relation to leadership behaviour. | There is a lack of clarity regarding to what extent dehumanization and objectification are different concepts and how they pertain to a broader conception of dehumanization and humaneness, including uniquely human qualities. | |

| (Sainz et al., 2023) | To study how perceptions of economic inequality and unfairness in the distribution of resources can influence individuals’ perceptions of dehumanization and self-objectification and trigger detrimental consequences in the workplace. | Inequality and unfairness increase perceived organizational dehumanization, which is related to greater self-objectification and reducing dignity. | |

| (Shields & Grant, 2010) | To examine how, under contemporary ‘human resource management’ (HRM), labour management theory and practice have developed into a sophisticated project designed to psychologize the employee subject into a resource object. | Management seeks to make human abilities, attitudes, and emotions—the basis of the status of the employee as a social and organizational entity—classifiable, measurable, and, therefore, easier to manage. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vveinhardt, J. Employee Objectification in Modern Organizations: Who Has Swept Personal Dignity Under the Carpet? Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 447. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110447

Vveinhardt J. Employee Objectification in Modern Organizations: Who Has Swept Personal Dignity Under the Carpet? Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(11):447. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110447

Chicago/Turabian StyleVveinhardt, Jolita. 2025. "Employee Objectification in Modern Organizations: Who Has Swept Personal Dignity Under the Carpet?" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 11: 447. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110447

APA StyleVveinhardt, J. (2025). Employee Objectification in Modern Organizations: Who Has Swept Personal Dignity Under the Carpet? Administrative Sciences, 15(11), 447. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110447