Gendered Perspectives in Capacity Development and Financial Literacy in the Mining Industry in Mpumalanga Province

Abstract

1. Introduction

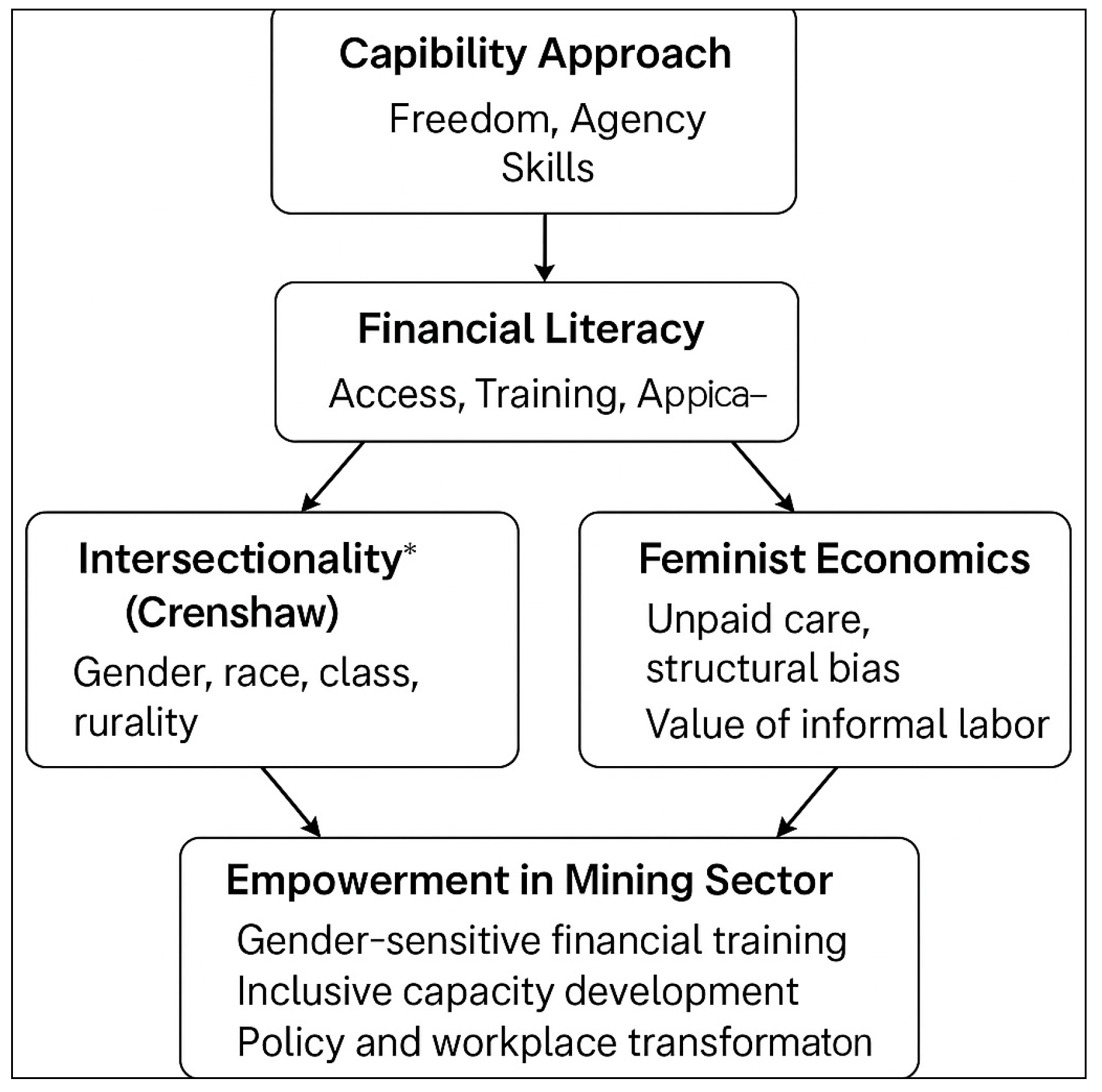

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Capability Approach

2.2. Intersectionality

2.3. Feminist Economics

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design and Methodology

3.2. Ethical Considerations

3.3. Data Availability

4. Results

4.1. Access to Financial Literacy Programs

“We hear about financial workshops, but they are not well-publicised, and no one ensures we can attend”.(Participant 4)

“I learned about budgeting from a colleague who attended a program, but nothing is offered in our department”.(Participant 8)

4.2. Gender Norms and Cultural Expectations: Negotiating Authority

“Even if I manage my finances well, my family expects me to consult my husband before making any major decisions”.(Participant 7)

“I wanted to invest in a small business, but my supervisor said it’s not appropriate for women in mining to take such risks”.(Participant 11)

“We are learning to challenge these expectations. Financial knowledge gives us the confidence to make our own decisions”.(Participant 2)

4.3. Community-Based Learning and Peer Support: A Collective Response

“We started a savings group for women in our department. It’s small, but it keeps us in check”.(Participant 3)

We share breaks together talking about bonuses to work or how to prepare our children for education”.(Participant 9)

“When we discuss with each other, we feel comfortable asking and sharing struggles. It’s not formal training”.(Participant 4)

4.4. Digital Financial Inclusion and Technological Disparities

“Yes, I have a phone, but I get nervous when I try to use those apps. If I press the wrong button, what if I lose my money?”.(Participant 5)

“When there’s a new app, I have to ask my son or husband to show me. They think I’m slow, so I stop asking”.(Participant 6)

“The apps need data all the time, and I can’t afford to keep buying bundles just to check my balance or track spending”.(Participant 10)

4.5. Perceived Empowerment and Development of Agency

“Now I can budget for my family and save for my children’s education. I feel more in control”.(Participant 2)

“I helped my sister start a small business with the savings tips I learned. It’s changing how we think about money”.(Participant 12)

“Since I started managing finances more appropriately, my husband pays more respect to my opinion. We both decide now”.(Participants 3)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abiodun, D., Hamzat, L., & Bamidele, A. (2021). Advancing financial literacy through behavioral analytics and custom digital tools for inclusive economic empowerment. International Journal of Engineering Technology Research & Management, 5(10), 130. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, A. H., Green, C., & Jiang, F. (2020). Mobile money, financial inclusion and development: A review with reference to African experience. Journal of Economic Surveys, 34(4), 753–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akala, B. (2019). Intersecting human development, social justice and gender equity: A capability option. Education as Change, 23(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriamahery, A., & Qamruzzaman, M. (2022). Do access to finance, technical know-how, and financial literacy offer women empowerment through women’s entrepreneurial development? Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 776844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, S., & Rathore, A. S. (2021). Dalit feminist theory. In Zubaan books. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (2023). Cultivate self-efficacy for personal and organizational effectiveness. In Principles of organizational behavior: The Handbook of evidence-based management (3rd ed., pp. 113–135). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Beoku-Betts, J. A., & M’Cormack-Hale, F. A. (2022). Understanding the politics of women and gender equality in Sierra Leone: Opportunities and possibilities. In War, women and post-conflict empowerment: Lessons from Sierra Leone (pp. 3–22). Zed Books. [Google Scholar]

- Chikwe, C. F., Kuteesa, C., & Ediae, A. A. (2024). Gender equality advocacy and socio-economic inclusion: A comparative study of community-based approaches in promoting women’s empowerment and economic resilience (2022). International Journal of Scientific Research Updates, 8(2), 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J., Dutz, M. A., & Usman, Z. (2020). The future of work in Africa: Harnessing the potential of digital technologies for all. World Bank Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary, H., & Jain, H. (2023). Addressing financial exclusion through financial literacy training programs: A systematic literature review. Empirical Research in Vocational Education and Training, 15(1), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortesi, S., Hasse, A., Lombana-Bermudez, A., Kim, S., & Gasser, U. (2020). Youth and digital citizenship+ (plus): Understanding skills for a digital world (2020-2). Berkman Klein Center Research Publication. [Google Scholar]

- De Haas, H. (2021). A theory of migration: The aspirations-capabilities framework. Comparative Migration Studies, 9(1), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dejaeghere, J. G. (2020). Reconceptualizing educational capabilities: A relational capability theory for redressing inequalities. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 21(1), 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebirim, G. U., Ndubuisi, N. L., Unigwe, I. F., Asuzu, O. F., Adelekan, O. A., & Awonuga, K. F. (2024). Financial literacy and community empowerment: A review of volunteer accounting initiatives in low-income areas. International Journal of Science and Research Archive, 11(1), 975–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortson, B. L., Klevens, J., Merrick, M. T., Gilbert, L. K., & Alexander, S. P. (2016). Preventing child abuse and neglect: A technical package for policy, norm, and programmatic activities. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, L., & Romero, C. (2017). In the mind, the household, or the market? concepts and measurement of women’s economic empowerment. Concepts and measurement of women’s economic empowerment (May 31, 2017). World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 8079. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Gillwald, A., Govan-Vassen, N., Banya, R., Galpaya, H., & Barrantes, R. (2023). Digitalisation for a just social compact: Global south lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Institute of Peruvian Studies, LIRNEasia, and Research ICT Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Gower, S., Jeemi, Z., Forbes, D., Kebble, P., & Dantas, J. A. (2022). Peer mentoring programs for culturally and linguistically diverse refugee and migrant women: An integrative review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helsper, E. (2021). The digital disconnect: The social causes and consequences of digital inequalities. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hilson, A. E. (2025). Women in development minerals: Artisanal and small-scale mining, governance, and the SDGs. Environmental Science & Policy, 164, 103980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilson, G., Bartels, E., & Hu, Y. (2022). Brick by brick, block by block: Building a sustainable formalization strategy for small-scale gold mining in Ghana. Environmental Science & Policy, 135, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, S., Haq, S., Jameel, A., Hussain, A., Asif, M., Hwang, J., & Jabeen, A. (2020). Impacts of rural women’s traditional economic activities on household economy: Changing economic contributions through empowered women in rural Pakistan. Sustainability, 12(7), 2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N. (2020). Women’s empowerment and economic development: A feminist critique of storytelling practices in “randomista” economics. Feminist Economics, 26(2), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N. (2021). Gender equality, inclusive growth, and labour markets. In Women’s economic empowerment (pp. 13–48). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kansake, B. A., Sakyi-Addo, G. B., & Dumakor-Dupey, N. K. (2021). Creating a gender-inclusive mining industry: Uncovering the challenges of female mining stakeholders. Resources Policy, 70, 101962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappler, S., & Lemay-Hébert, N. (2021). From power-blind binaries to the intersectionality of peace: Connecting feminism and critical peace and conflict studies. In Feminist interventions in critical peace and conflict studies (pp. 34–50). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kellner, D., & Share, J. (2019). The critical media literacy guide: Engaging media and transforming education (Vol. 2). Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari, D. (2020). Women’s economic empowerment: An integrative review of its antecedents and consequences. Journal of Poverty, Investment and Development, 56, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Lamberg, E. (2025). Shifting boundaries, dismantling brick walls: Feminist knowledge in the struggles to transform economic thinking and policy. Gender, Work & Organization, 32(1), 100–115. [Google Scholar]

- Lekwadu, M. I. (2020). The experiences, challenges and coping strategies of women residing around the mining communities: The case of Driekop community, Limpopo province, South Africa. University of South Africa (South Africa). [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie, A., & Chiang, T. H. (2023). The human development and capability approach: A counter theory to human capital discourse in promoting low SES students’ agency in education. International Journal of Educational Research, 117, 102121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magida, A. (2023). The nexus between the digital divide and social cohesion and their socio-economic drivers in South Africa [Doctoral dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand]. [Google Scholar]

- Mako Robinson, C. (2024). The power of her voice: An interpretative phenomenological study exploring the career experiences of women middle-level leaders [Doctoral dissertation, Antioch University]. [Google Scholar]

- Melubo, K. D., & Musau, S. (2020). Digital banking and financial inclusion of women enterprises in Narok County, Kenya. International Journal of Current Aspects in Finance, Banking and Accounting, 2(1), 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minow, M. (2021). Equality vs. equity. American Journal of Law and Equality, 1, 167–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzari, T., Shava, G. N., & Shonhiwa, S. (2022). Qualitative research paradigm, a key research design for educational researchers, processes and procedures: A theoretical overview. Indiana Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 3(1), 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ndlovu, P. (2024). Women’s right to access family planning, information and services during humanitarian emergencies: A case of cyclone Idai in Chipinge and Chimanimani districts of Zimbabwe [Doctoral dissertation, University of the Western Cape]. [Google Scholar]

- Nondwangu, K. (2022). Gender-barriers faced by women entrepreneurs in the South African mining industry university of pretoria (South Africa). Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/d05794ec091297b34a4cb5b3e4b3e278/1?cbl=2026366&diss=y&pq-origsite=gscholar (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Pervin, N., & Mokhtar, M. (2022). The interpretivist research paradigm: A subjective notion of a social context. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development, 11(2), 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramella, F., & Manzo, C. (2020). The economy of collaboration. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Rimmer, J. (2023). Gender transformative approaches–a silver bullet for gender equality? Investigating the effects of the GALS methodology on gender transformative change for coffee smallholders, as implemented in the circular coffee project in San Martín, Peru [Master’s thesis, Utrecht University]. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, M., Nussbaum, M., Guerrero, O., Chiuminatto, P., Greiff, S., Del Rio, R., & Alvares, D. (2022). Integrating a collaboration script and group awareness to support group regulation and emotions towards collaborative problem solving. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 17(1), 135–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, G. K. (2024). Involving people with lived experience in the evaluation of a mental health peer support project in Uganda [Doctoral dissertation, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine]. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. (2020). The possibility of social choice. In Shaping entrepreneurship research (pp. 298–339). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S. G., & Sinkford, J. C. (2022). Gender equality in the 21st century: Overcoming barriers to women’s leadership in global health. Journal of Dental Education, 86(9), 1144–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultana, F. (2020). Embodied intersectionalities of urban citizenship: Water, infrastructure, and gender in the global south. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 110(5), 1407–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D., Peng, B., Ma, R., & Sum, K.-w. R. (2025). Dispelling stigma and enduring bias: Exploring the perception of esports participation among young women. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 12(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Niekerk, A. J. (2020). Inclusive economic sustainability: SDGs and global inequality. Sustainability, 12(13), 5427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Theme | Description | Relationship with Other Themes |

|---|---|---|

| Limited access to financial literacy opportunities | Many participants reported inadequate access to financial education, especially early in their careers. | Influences digital exclusion and decision-making; linked to low levels of financial confidence. |

| Gendered barriers in workplace culture | Patriarchal norms and male-dominated leadership structures restrict women’s advancement and financial autonomy. | Shapes experiences in all other themes; exacerbates inequality and limits training access. |

| Cultural and social expectations on women’s financial roles | Traditional norms expect women to prioritise household duties and caregiving over personal economic development. | Limits their ability to invest in their own capacity development or pursue advanced roles. |

| Digital exclusion in financial tools and platforms | Participants expressed difficulties in accessing digital financial platforms due to language barriers and limited ICT training. | Reinforces financial illiteracy and reflects structural inequalities. |

| Aspirations for economic independence and leadership | Despite challenges, most women articulated strong goals for financial empowerment and leadership in the mining sector. | Motivates resistance to barriers; highlights the transformative potential of targeted programs. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baker, S.M.; Ngonyama-Ndou, T. Gendered Perspectives in Capacity Development and Financial Literacy in the Mining Industry in Mpumalanga Province. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 446. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110446

Baker SM, Ngonyama-Ndou T. Gendered Perspectives in Capacity Development and Financial Literacy in the Mining Industry in Mpumalanga Province. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(11):446. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110446

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaker, Sabelo Merrander, and TL Ngonyama-Ndou. 2025. "Gendered Perspectives in Capacity Development and Financial Literacy in the Mining Industry in Mpumalanga Province" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 11: 446. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110446

APA StyleBaker, S. M., & Ngonyama-Ndou, T. (2025). Gendered Perspectives in Capacity Development and Financial Literacy in the Mining Industry in Mpumalanga Province. Administrative Sciences, 15(11), 446. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110446