1. Introduction

Entrepreneurial intention is defined as a conscious state of mind that precedes the start of a company or entrepreneurial venture (

Bird, 1988;

Obschonka et al., 2010). Despite the growing importance of entrepreneurship for innovation and economic growth, we still lack a clear understanding of how alternative funding mechanisms operate in Widening countries. The scarcity of comparative, multi-country evidence on venture capital, business angels, crowdfunding, and grants makes this topic both timely and urgent. Previous studies have examined individual funding models or single-country cases, but there is still no comprehensive analysis of how these mechanisms jointly affect firm performance and business model adaptation across Widening countries. Studies have indicated that entrepreneurial intentions are often associated with access to finance, and that higher levels of financial literacy significantly increase the likelihood of entrepreneurial behavior (

Shahriar et al., 2024;

Rashid et al., 2025;

Audretsch et al., 2021).

Small and medium-sized enterprises, especially micro-enterprises and entrepreneurs, face difficulties in obtaining the necessary financial resources required for the development of their businesses and for reaching the scale-up phase. This issue is even more pronounced in developed countries (

Zavatta, 2008). Without adequate funding, SMEs may be unable to continue their investments and sustain day-to-day operations (

Temelkov et al., 2018). Research indicates that various financing methods positively influence creativity among entrepreneurs and, consequently, within small and medium-sized firms (

Romero Alvarez et al., 2025). Economic conditions, such as market stability and finance accessibility, serve as external elements that either facilitate or obstruct entrepreneurial efforts (

Saoula et al., 2025). Research suggests that youth entrepreneurial intentions are largely determined by business knowledge, education, and access to finance (

Rusu et al., 2022). Positive intentions to launch a business are more likely to develop when there is easier access to financial resources for early-stage enterprise financing (

Saoula et al., 2025).

The development of innovations, however, often requires financing models that differ from traditional ones (

Crudu, 2019). Traditional financing largely influences the creation of innovation within companies. However, firms often avoid relying on traditional sources of finance. The main reason is that traditional financing, such as equity capital and bank loans, tends to discourage investment in innovative projects due to their inherent riskiness (

Atanassov et al., 2007). For a company, securing financing that enables research and development is of critical importance. This study suggests that further research on the effects of different financing mechanisms across countries would yield varying results due to research factors that are difficult to capture when observing a single country (

Frimanslund et al., 2023;

Hall, 2005).

The existing literature lacks comprehensive, cross-country evidence on how alternative financing mechanisms influence firm performance and business model adaptation during the post-investment period in Widening countries. Furthermore, while global indices such as the GEI provide useful benchmarks, their link to actual firm-level financing outcomes remains underexplored. This creates a gap in understanding the extent to which financing mechanisms support the transformation of entrepreneurial intentions into entrepreneurial action in less-developed entrepreneurial ecosystems. A particular relevance of this study lies in its focus on countries that, according to the European Commission’s classification, belong to the group of Widening countries. However, although these ecosystems may appear similar at first glance, the results demonstrate that national instruments and policy frameworks influence company success in different ways.

This study aims to examine how different forms of financing influence business improvement and the transformation of entrepreneurial intentions into entrepreneurial action. The combined post-investment effects of multiple financing mechanisms are still poorly understood, especially in the context of Widening countries, even though prior research has focused on individual funding instruments or single-country cases. This study addresses this research gap by examining to what extent alternative financing mechanisms facilitate the transformation of entrepreneurial intentions into entrepreneurial actions among innovative SMEs. By analyzing firms from selected Widening countries, the research generates new insights into how financing mechanisms affect development, revenues, employment, customer base, and business model adaptation. Beyond filling a gap in existing literature, this study contributes theoretically by linking post-investment adaptation to the entrepreneurial finance framework and by providing guidance for policymakers and funding institutions in Widening regions. The findings highlight the importance of designing context-sensitive funding programs that integrate grants, venture capital, business angels, and crowdfunding to maximize post-investment outcomes. Policymakers can use these insights to align financial instruments with national innovation strategies and strengthen entrepreneurial ecosystems. Overall, the study provides one of the first cross-country analyses of alternative funding mechanisms in Widening countries and offers practical recommendations for fostering innovation-driven entrepreneurship and sustainable growth in the region.

2. Theoretical Framework

Entrepreneurship is an intentional process in which an individual’s goal is to create a business, and according to Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior, finance acts as an external enabler that transforms this intention into concrete entrepreneurial action (

Ajzen, 1980,

1991;

Lortie & Castogiovanni, 2015).

The importance of small and medium-sized enterprises (companies with fewer than 200 employees) for a country’s economy is already well known. SMEs make up a large part of the business centers of economies, and every economy strives again to promote the growth of small and medium-sized enterprises. Employment, economic growth, and innovation come from SMEs, which further strengthens their importance (

Algan, 2019). SMEs represent around 90% of all businesses, provide between 60 and 70% of jobs, and generate about half of global GDP. Despite this significance, high failure rates (

Neagu, 2016) and persistent financial constraints (

Beck & Demirguc-Kunt, 2006) indicate that the sustainability of SMEs depends strongly on the design and accessibility of financing instruments (

Vlassas et al., 2023).

The importance of small and medium-sized enterprises lies in their large role in a country’s economy. SMEs are one of the sources of entrepreneurial opportunities, innovation, and the creation of new jobs. That is why authors point out that they play a key role in a country’s economy (

Edobor & Sambo-Magaji, 2025;

Neagu, 2016).

The independence of the entrepreneur to start their own business depends on the existence of an idea, entrepreneurial culture, the level of risk the entrepreneur is willing to take, available support, and the education system. The level of entrepreneurial attitudes and perceptions influences the overall performance of the economy. Such attitudes must be constantly encouraged by governments (

Isac, 2013;

Vaduva, 2004).

In the literature, entrepreneurship is recognized as having an important role in driving innovation, economic growth, and welfare, as well as in creating jobs. Over time, researchers have had different views on the link between economic development and entrepreneurship. Innovation is also seen as a driving force of national economic development. Because of this, innovative entrepreneurship has come to be viewed as a key factor in modern economic growth (

Crudu, 2019).

Entrepreneurs boost economic growth by introducing innovative technologies, products, and services. Increased competition from entrepreneurs challenges existing firms to become more competitive. Entrepreneurs provide new job opportunities in the short and long term,

Audretsch (

2002),

Kritikos (

2024), and

Surya et al. (

2021) state that technological innovations increase business growth. In their study, they note that 97% of the growth of small and medium-sized enterprises is driven by government policies, support from venture capital, and strengthening of resource capacities. As part of the economic development strategy, based on their research, they propose technological innovations.

At the same time, entrepreneurs face financial stress because of low working capital, lack of collateral for new bank loans, and the ongoing pressure to cover interest, installments, wages, rent, and taxes (

Gautam & Gautam, 2024). However, many countries find it difficult to develop dynamic entrepreneurial ecosystems because of problems with access to finance, regulatory barriers, and inefficient capital allocation (

Myronchuk et al., 2023). These problems are especially important in the early and scaling stages of startups, when limited financial resources restrict their growth opportunities (

Prokopenko et al., 2025). According to

Onyekwelu et al. (

2023), it is essential that all stakeholders recognize the need to design financial instruments that can provide emerging entrepreneurs with access to capital.

Howell (

2017) emphasizes that innovation capital financing at the startup and early stages contributes to positive outcomes in terms of financial performance, revenue growth, business survival, and overall success. Having outlined the theoretical foundations and previous research, the following section focuses on financing entrepreneurial ventures, with particular attention to the challenges and opportunities relevant to SMEs in the Widening countries. Entrepreneurial intention reflects the motivation to start a business, but intentions alone are not sufficient. The availability and type of financing often determine whether these intentions are translated into concrete entrepreneurial action (

Howell, 2017;

Klein et al., 2019).

2.1. Entrepreneurial Venture Financing

Entrepreneurship represents the creation of new services and technologies based on the ideas and concepts of entrepreneurs, serving as the foundation of business activity. The essence of entrepreneurship lies in innovation (

Hisrich et al., 2017;

Pan et al., 2022). A very common formation of an entrepreneurial idea is a startup, where the entrepreneur’s initial concept develops into a growing company. Startups are often regarded as essential drivers of modern economic development (

Hisrich et al., 2017). Their life cycle typically passes through several stages: seed, start-up, early growth, and later stage. In the first phases, financing mostly comes from internal sources such as the founder’s capital, family and friends (the so-called 3Fs), bootstrapping, or business alliances (

Winborg & Landström, 2001). As the firm grows, it requires external financing, bank loans, government programs and grants, or professional investors such as business angels, venture capital funds, corporate investors, and later public offerings (IPO). Literature particularly emphasizes the importance of business angels and venture capital in supporting high-growth start-ups (

Harrison & Mason, 2000). Certain authors note that financing of companies begins at the seed stage. However, funding available for this phase is very limited and primarily serves to provide companies with sufficient resources to develop a prototype (

Peixoto et al., 2023).

The situation with entrepreneurship and SMEs is rather complex and challenging. For this reason, financing small business development requires a broader range of financial instruments. The lack of tradition and experience in running businesses often prevents banks from providing adequate loans to entrepreneurs and SMEs (

Zarezankova-Potevska, 2017).

Milutinović et al. (

2018) describe the main division of innovation financing as internal and external. Internal financing includes funds from retained earnings, revenues from sales, and company assets. External financing refers to sources outside the company, such as tax incentives, banks, business angels, venture capital funds, crowdfunding platforms, and microcredits.

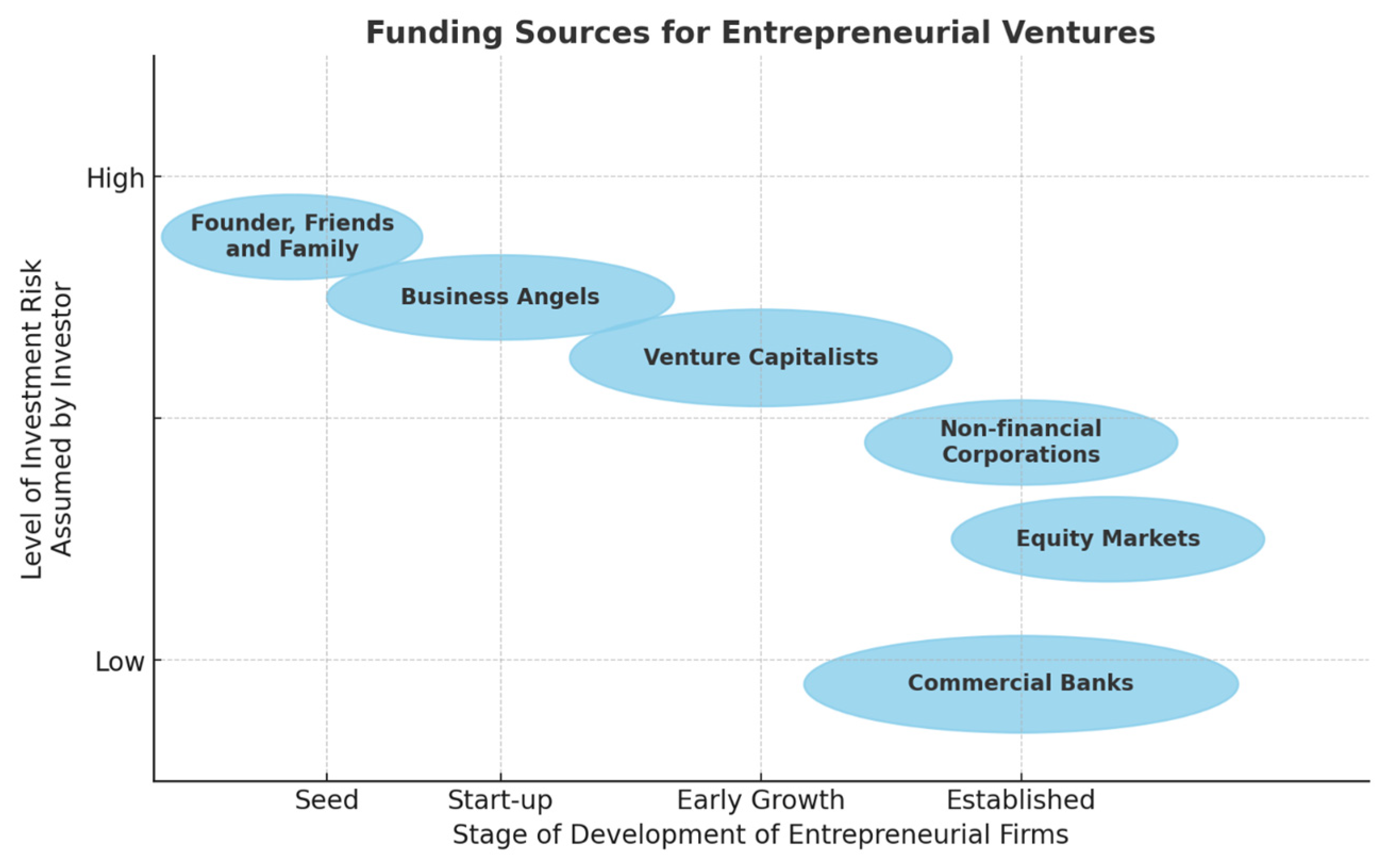

Figure 1 illustrates the alignment of funding sources with the stage of entrepreneurial firm development, showing that investors assume higher risk in the early phases (e.g., founders, friends, family, and business angels), while lower-risk financing (e.g., banks and equity markets) becomes more accessible in later, established stages (

Osnabrugge & Robinson, 2000).

As presented in

Figure 1, financing mechanisms differ not only by risk profile but also by their role in shaping firm development. This conceptual model links each financing stage with potential changes in business performance and model adaptation, providing the basis for the hypotheses tested in this study. Companies that receive this type of capital have lower chances of surviving in the market compared to those that use other forms of innovation financing. The reason is that banks, when approving credit funds, focus mainly on financial evidence of the owner’s creditworthiness rather than on the company’s human capital. In addition, some business owners are unable to meet all the conditions set by banks for granting financial resources, which makes it easier for them to seek funding from alternative sources (

Åstebro & Bernhardt, 2003).

Tax incentives have already become a common policy tool across Europe; however, these incentives only minimally reduce the tax burden of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). What makes them problematic is that they primarily benefit micro-enterprises, while SMEs often do not receive such relief. This raises a legitimate question of whether tax incentives are the right mechanism, since they do not support SMEs and entrepreneurs, but rather micro-enterprises, which contribute little to innovation or job creation. Firms, facing high risks, often cannot benefit from these incentives because they lack sufficient revenues in the early stages. Moreover, the current tax incentives are not strong enough to support innovation or growth in SMEs. The authors conclude that tax incentives create more complications than they solve when it comes to the key challenges of innovative enterprises (

Bergner et al., 2017).

Grants are another option through which entrepreneur companies can obtain financial resources for the realization of innovations. Grants prepare and stimulate companies for further growth and future rounds of financing. In addition to financial support, innovation grants also provide non-financial assistance such as mentoring and networking, which further contributes to the development of firms and creates long-term effects. Along with grants, tax incentives also influence the additional growth of companies (

Testa et al., 2019).

Hall et al. (

2016) state that subsidies in the form of alternative financing instruments, such as grants, ease financial constraints and stimulate innovation. Companies need financial support to grow. Traditional sources of funding, such as bank loans, are not designed to enhance the business development of firms.

Some authors point out that companies receiving support in the form of grants have greater chances of surviving the “valley of death.” Firms that obtain grants also find it easier to secure further financing from business angels or venture capital in later stages of development (

Islam et al., 2018). In the literature, grants appear as an instrument that makes it easier to obtain other forms of capital, such as business angels, crowdfunding platforms, and venture capital funds (

Islam et al., 2018;

Shinkle & Suchard, 2019;

Testa et al., 2019).

Business angels play an important role in the development of companies. Similarly to grants, they do not provide only capital but also add extra value. Angel investors accelerate the growth of firms when they are between the seed and early stage (

Dat, 2021).

Politis (

2008) identifies the additional value that business angels bring to companies, which is reflected in their strategic role, supervisory role, resource acquisition, and mentoring. The strategic role includes participation in shaping business strategy, including the development of business models. Besides these contributions, the study also points out that the post-investment phase has not been sufficiently researched. The authors emphasize that further investigation of this stage could provide valuable insights into the link between financing instruments and business improvement.

Venture capital investors and business angels evaluate both the market and financial aspects of the venture, with the business model canvas serving as the key entry document. Banks, on the other hand, focus on the liquidity of the company, where the business plan is the main requirement. What remains certain is that whichever source they use, firms must adapt their business models to the expectations of their financiers (

Mason & Stark, 2004). Firms in the early stages of development face difficulties in accessing traditional sources of finance due to a lack of credibility and high risk. Some studies point out that the geographical distribution of available venture capital significantly influences the extent to which it is used by companies (

Block et al., 2024;

Colombo et al., 2019). Venture capital funds provide not only financial support but also valuable knowledge, experience, and business networks. Despite negative aspects such as the cyclical nature of capital supply and the growing risk aversion among investors, venture capital remains a crucial factor for fostering innovation in the economy (

Firlej, 2018).

Crowd-funding platforms can provide startups not only with financial support but also with non-financial support, such as market insights and marketing (

Mora-Cruz & Palos-Sanchez, 2023). Crowdfunding platforms support innovation in two ways. The first is by providing firms with a new source of financing. The second is through the participation of the crowd, which gives feedback on the company’s products or services. Firms can obtain different types of information from this feedback, such as ideas for product development during and after the campaign, as well as insights into product demand. The study notes that it would be interesting to further examine the role of crowdfunding platforms and the dynamics of firm development (

Hervé & Schwienbacher, 2018).

The problem with traditional sources of financing, such as banks, lies in the requirement of liquidity to repay borrowed funds. Loans or credits obtained from banks must be repaid with interest, which for companies with unstable or non-existent customers represents an additional burden. Taking bank loans increases the risk of failure for ventures. For this reason, these companies turn to alternative sources of financing.

2.2. Alternative Financing Instrument

Hall (

2010) explains that investments in innovation differ from regular investments due to several specific characteristics. Most are directed toward research and development, design, marketing, and training, which creates intangible assets. These assets are closely tied to human capital, meaning their value often depends on the knowledge and expertise of employees. Innovation is also marked by high levels of risk and uncertainty, especially in the early stages of projects, when outcomes are difficult to predict. This uncertainty can be so extreme that standard risk assessment methods cannot be applied. In addition, intangible assets usually have little value in terms of sales, which makes debt financing less suitable. For these reasons, companies typically rely more on equity financing than on debt. While some authors recognize bank loans and tax incentives as instruments for financing firms (

Åstebro & Bernhardt, 2003;

Milutinović et al., 2018), in this study they are not considered alternative financing instruments, since they create debt and therefore increase risk. By contrast, equity-based mechanisms are designed to mitigate such risks. In this context, alternative financing instruments refer to business angels, venture capital funds, crowdfunding platforms, and grants, all of which are intended to provide firms with resources that foster growth and development (

Bessière et al., 2020;

Hall, 2010).

It is well established that different types of financing influence company performance and reduce the risk of entrepreneurial failure. However, the post-investment phase and the specific effects of various forms of capital remain insufficiently explored. The following hypotheses aim to address this gap and provide a deeper understanding of these relationships.

In this study, the financing instruments are not categorized as equity-based or non-equity-based, nor as pre- or post-investment, since such classifications do not fully reflect their operational dynamics. Venture capital and business angels represent equity-based forms, while grants and tax incentives are non-equity mechanisms. Crowdfunding, however, can take both forms, depending on the platform model. Moreover, the pre- and post-investment distinction is not applicable, as this study focuses on the effects of financing on firm performance rather than the timing of investment. Therefore, the instruments are analyzed within an integrated framework emphasizing their combined impact on business improvement and adaptation.

3. Hypotheses Development

The progressive growth of a company is influenced by combining different forms of equity-based financing, such as venture capital funds, crowdfunding platforms, or business angels. These financing instruments reduce the risks faced by firms (

Bessière et al., 2020). Early-stage financing of entrepreneurial ventures represents a vital part of enterprise development. Certain authors note that limited financial opportunities often prevent entrepreneurs from realizing their innovations. The authors point out that the shift in financing of firms, particularly the emergence of alternative financing instruments, provides entrepreneurs with greater security in carrying out their innovations (

Klein et al., 2019;

Svetek, 2022).

Gilbert et al. (

2006) and

Christian Korunka et al. (

2011) identify revenue growth, customer growth, and employment growth as the main indicators of firm performance. Some authors also point out that the companies achieving the highest growth are those that manage to introduce adequate changes in key elements of the Business Model Canvas, particularly in the dimensions related to delivering value to customers (

Slávik, 2019). Based on the literature review, the first hypothesis proposed in this study is as follows:

Hypothesis 1. Companies financed through grants, business angels, venture capital funds, or crowdfunding platforms show growth in employment, customer base, revenues, and stage of development compared to the period before financing.

The business model plays an important role for companies (

García-Gutiérrez & Martínez-Borreguero, 2016).

Teece (

2010) defines a business model as a framework that explains the logic behind value creation, supported by data and evidence that justify the value proposition for the customer. Additionally, it outlines a sustainable structure of revenues and costs for the enterprise delivering this value. It is developed at the beginning of the venture, when only basic assumptions about the market are made. At this stage, firms usually do not consider the financial sustainability of their projects (

Satheesh Raju et al., 2020). Companies that apply business models can achieve up to four times higher returns on investment. Business model innovation can ensure sustainability and accelerated growth for firms (

Djuraeva, 2021). Because of the low probability of designing a business model that works perfectly from the start, companies must constantly innovate their business models. This process of business model innovation is also referred to as pivoting. For firms, this is often an advantage, as their agility allows them to adapt and modify segments of the Business Model Canvas more easily than large corporations. However, limited financial resources restrict this advantage to only one attempt (

Comberg et al., 2014). Some authors define six factors influencing the process of business model innovation: (1) the role of the founder, (2) business model sustainability, (3) cash flow and financing, (4) market conditions, (5) company finances, and (6) new technology. Although the sample analyzed was relatively small (four companies), the findings suggest that financing methods have a significant impact on changing key elements of the Business Model Canvas (

Comberg et al., 2014). According to the resource-based view (RBV), the ability to adapt the business model after receiving external funding reflects a firm’s capacity to reconfigure and leverage its resources, which strengthens competitiveness and enhances performance. Based on these insights, the second hypothesis of this study is formulated as follows:

Hypothesis 2. Companies that adapt their business model, specifically their revenue model, after receiving alternative financing instruments are more likely to achieve positive business outcomes.

Business improvement is also reflected in networking, market expansion, support for company development, and changes in business practices. This study highlights the importance of examining the impact of alternative financing instruments on firms. It is also necessary to understand the interdependencies that arise from combining different forms of financing and their influence on the business improvement of newly established enterprises (

Clara Wijaya Rosa et al., 2019). “Widening countries” refers to EU member states with lower performance in innovation and research, aiming to bridge the innovation gap through specific programs and funding under initiatives such as Horizon Europe and Horizon 2020. These programs support entrepreneurship and startups by strengthening their business, investor, and technology readiness, thereby improving their competitiveness and participation in Europe’s innovation ecosystem. The Global Entrepreneurship Index (GEI) reflects the overall health of a country’s entrepreneurial ecosystem (

Opinium, 2025). This hypothesis seeks to demonstrate a potential relationship between the Global Entrepreneurship Index (GEI) and the access to alternative sources of financing. Institutional theory states that the level of sophistication and quality of a nation’s institutional environment, including its financial systems, innovative policies, and regulatory frameworks, has a direct impact on how easily businesses can obtain outside funding and how entrepreneurial ecosystems grow. Based on this, the third hypothesis of this study is formulated as follows:

Hypothesis 3. Countries with higher GEI, among the selected, are more frequently financed through venture capital, business angels, grants, and crowdfunding compared to countries with lower GEI.

4. Materials and Methods

The target population in this study includes innovative small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that received at least one form of alternative financing grants, venture capital, business angel investment, or crowdfunding between 2020 and 2022. In this context, innovative SMEs are defined as firms that have introduced a new or significantly improved product, service, or business process within the past three years, in line with the

OECD (

2018) and the European Commission: Directorate-General for Research and Innovation and Hollanders classification. The study focuses on countries categorized as “Widening countries” according to the European Commission’s European Innovation Scoreboard (

European Commission et al., 2023). These include Serbia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Romania, Greece, and several additional EU Member States identified as having below-EU-average innovation performance. Business improvement was assessed through a structured online questionnaire designed in Google Forms. The instrument contained 81 questions, predominantly multiple-choice items, with several open-ended questions to capture qualitative insights. The questionnaire was distributed between May and June 2025 to 1500 company contacts obtained from national innovation agency databases, incubators, and startup directories. The final valid sample included 81 firms (response rate 5.4%). Respondents were primarily owners or senior managers, ensuring access to reliable strategic and financial information. In Romania, Greece, Serbia, and Bulgaria, data were additionally collected through direct interviews, which improved the response quality and reduced item nonresponse.

The survey examined both the period before receiving financing and the period after, comparing factors such as product development stage, number of employees, changes in business revenues, customer growth or decline, and modifications to business models. These indicators were identified as key measures of business improvement.

In the survey, product development was observed as one of the indicators of business improvement. Respondents were asked to position their firms within one of six development stages: ideation, conception, commitment, validation, scaling, and establishing. Although the terminology and number of stages vary across authors, the idea of sequential development from idea generation to market establishment is well recognized in the literature (

Winborg & Landström, 2001). Regarding financing, the study focused on alternative financing instruments, namely business angels, venture capital, grants, and crowdfunding. Prior research emphasizes the importance of such sources for supporting high-growth innovative firms, particularly in overcoming early-stage financing gaps (

Howell, 2017).

Additional performance indicators included revenues and employment. Revenues were measured using multiple-choice categories ranging from less than EUR 50,000 to more than EUR 1,000,000, while employment was captured through grouped categories, starting from 1–5 employees up to more than 50 (

OECD, n.d.).

For the presentation and identification of objective scientific regularities, the following general scientific methods were applied. To determine the relationship between input and output variables, descriptive and correlation analyses were used. All responses were treated as confidential and used exclusively for research purposes. To empirically test the proposed framework and hypotheses, a survey-based study was conducted among SMEs in selected Widening countries, as explained in the following section on methodology.

Survey Instrument and Diagnostic Tests

The survey consisted of structured questions designed to capture firm characteristics, financing sources, and performance indicators before and after funding. A sample of the key items is provided in

Appendix A,

Table A1. To ensure data quality and measurement reliability, several diagnostic tests were performed. Internal consistency was excellent (Cronbach’s α = 0.920; Spearman-ordinal α = 0.890; bootstrap α ≈ 0.917, 95% CI [0.848–0.958]). Construct validity was supported by factorability indicators (KMO = 0.776; Bartlett

p < 0.001). Multicollinearity remained within acceptable limits (max VIF = 7.55), and the expected non-normality of Likert-type data was addressed through non-parametric testing. Detailed diagnostic results are presented in

Appendix B.

5. Results Analysis

In this section, we present the results of the survey. Out of a total of 81 companies, 70.4% (56 firms) received some form of financing (some firms received more than one type of financing). Among these, 33% (19 firms) were financed through business angels, 3 companies obtained crowdfunding, 24.6% (14 firms) received venture capital, and 80.7% (46 firms) benefited from grants. Companies most frequently identify grants as the most significant form of support among these financing instruments.

H1. Companies financed through grants, business angels, venture capital funds, or crowdfunding platforms show growth in employment, customer base, revenues, and stage of development compared to the period before financing.

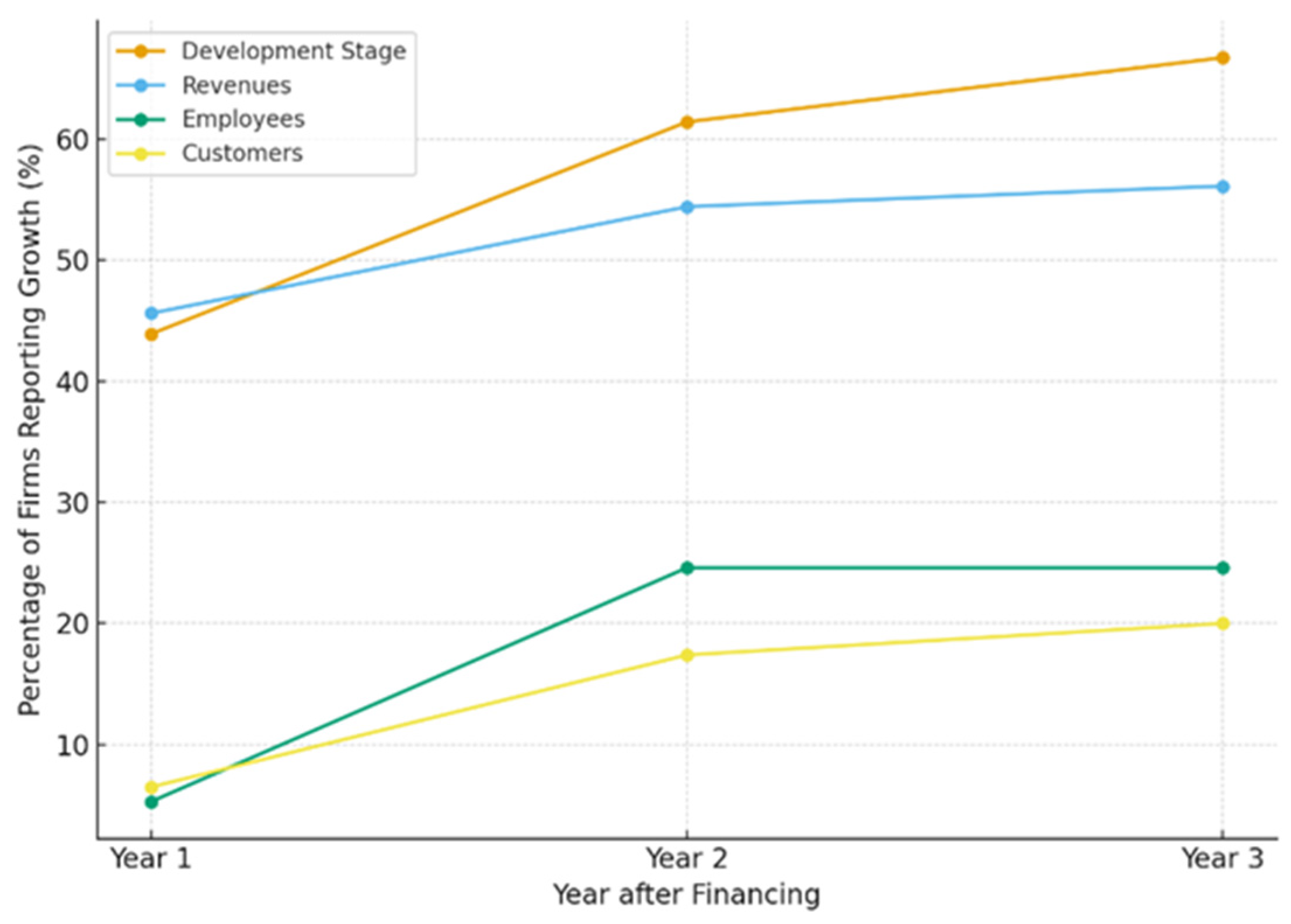

The descriptive results confirm positive trends across all four indicators when comparing the first, second, and third year after receiving financing (n = 57). As shown in

Figure 2, in the first year, 43.9% of firms reported progress in their development stage, while 36.8% remained at the same level and 19.3% regressed. By the third year, the share of firms reporting progress increased to 66.7%, with only 15.8% showing a decline. This indicates that financing supported advancement along the product development cycle. In the first year, 45.6% of companies recorded growth in revenues, while 33.3% remained stable and 21.1% experienced a decline. By the third year, 56.1% of firms reported revenue growth, suggesting that alternative financing instruments provided stability and long-term impact on financial performance. The impact on employment was weaker in the first year, with only 5.3% of companies reporting an increase in staff and the majority (80.7%) remaining stable. However, by the second and third year, more than 24% of firms reported growth in employment, showing a delayed but positive effect of financing on job creation. The effect on customer base was also gradual. In the first year, only 6.5% of firms saw growth, while 37% reported a decline. By the third year, 20% of firms had increased their customer base, and only 4.4% reported a decline. This indicates that firms need time to leverage financing to expand their market reach. However, the pace of growth varied: development stage and revenues responded more quickly, while employment and customer base showed delayed but stable positive effects. According to these trends, external financing largely speeds up a company’s internal development and revenue growth in the early years, while its effects on employment and market expansion take longer to manifest and are indicative of a phased process of business consolidation and scaling.

H2. Companies that adapt their business model, specifically their revenue model, after receiving alternative financing instruments are more likely to achieve positive business outcomes.

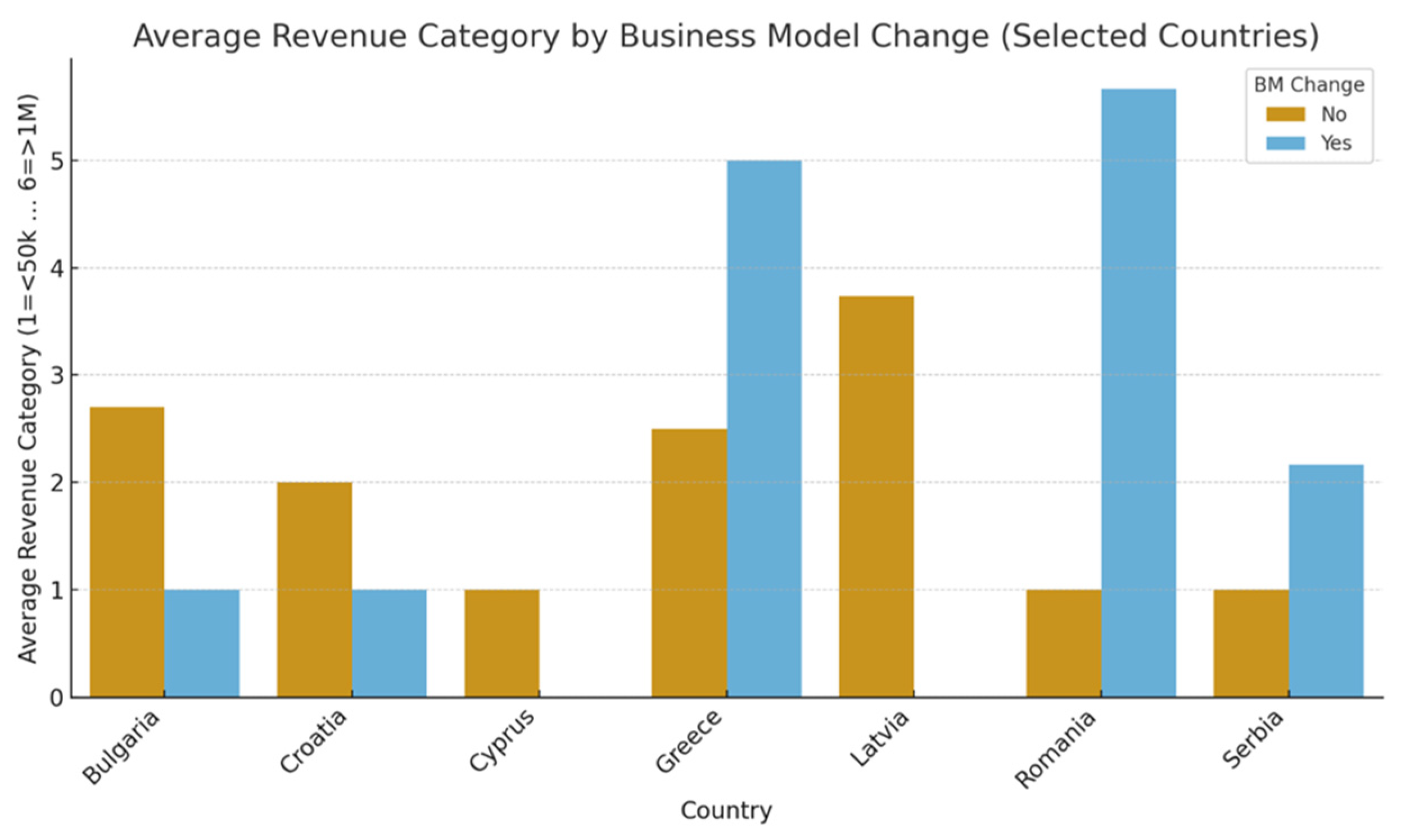

Descriptive results indicate that firms which reported changing their revenue model in the business model (15 out of 57) tended to move into higher revenue categories over time. In the first year, most firms that had not changed their business model remained concentrated in the lowest revenue category (<50,000 EUR), while firms that had adapted their revenue model appeared more frequently in higher ranges, including 50,000–100,000 EUR and even above 1,000,000 EUR. By the second and third year, this trend became more evident: firms with business model change were more represented in the 250,000–500,000 EUR and 500,000–1,000,000 EUR categories, while firms without change largely remained below 50,000 EUR. These descriptive findings suggest that business model adaptation may be linked to higher revenue performance.

To further examine this relationship, Spearman’s rank correlation was applied between business model change (binary) and revenue categories (ordinal). The correlation coefficient is a useful tool in statistics and research, as it helps us understand and quantify the relationships between different factors and variables (

Johnson & Wichern, 2002). The results showed weak and statistically insignificant associations across all three years (ρ = 0.11,

p = 0.50 in Y1; ρ = 0.14,

p = 0.45 in Y2; ρ = 0.06,

p = 0.72 in Y3). Similarly, Chi-square tests of independence between business model change and revenue categories did not indicate statistically significant results (χ

2 = 0.89,

p = 0.64 in Y1; χ

2 = 3.56,

p = 0.17 in Y2; χ

2 = 0.80,

p = 0.67 in Y3).

Taken together, the results provide partial support for H2. While descriptive evidence suggests that firms adapting their business models were more likely to achieve higher revenues in later years, the statistical tests did not confirm significant associations. This implies that business model adaptation may contribute to improved financial outcomes, but the effect is not robustly established in the current sample.

Figure 3 demonstrates notable cross-country differences in the link between business model adaptation and revenue performance. In Romania, Greece, and Serbia, firms that changed their revenue model consistently reached higher revenue categories, in some cases exceeding 500,000 EUR annually. Conversely, in Bulgaria and Croatia this pattern was reversed, with firms that did not change their revenue model reporting higher average revenues. Latvia represents a specific case where even firms without business model adaptation achieved comparatively high revenue levels.

Figure 3 indicates that firms adapting their business models achieved higher revenue levels in most countries, particularly in Romania, Greece, and Serbia, suggesting that business model adaptation is more effective in environments with stronger institutional and financial support.

H3. Countries with higher GEI, among the selected, are more frequently financed through venture capital, business angels, grant and crowdfunding compared to countries with lower GEI.

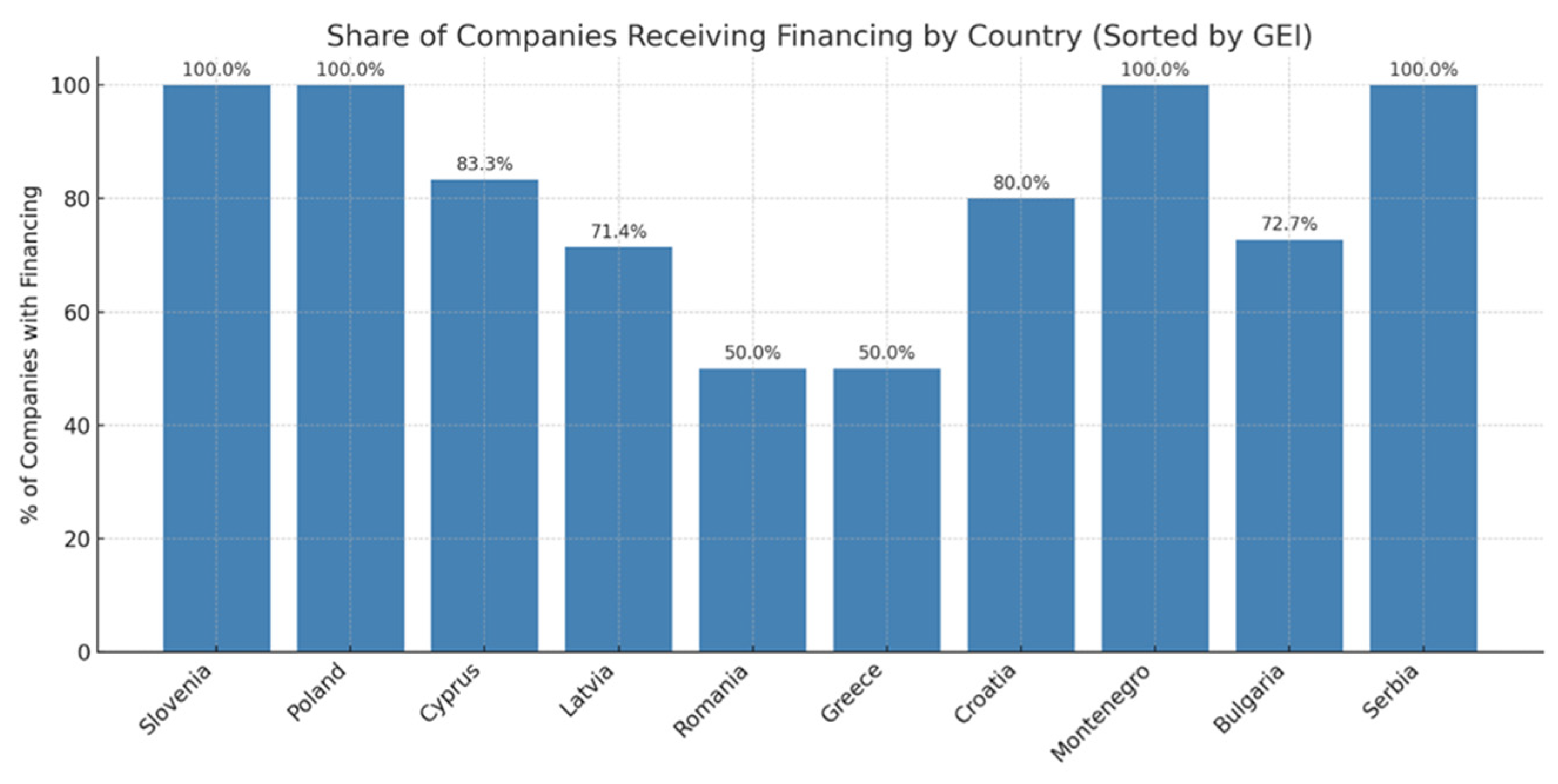

Descriptive results show heterogeneity across the countries analyzed. For instance, Slovenia, Poland, Serbia, and Montenegro reported that all surveyed firms received some form of financing (100%), while in Greece and Romania only half of the firms had access to financing. Intermediate cases include Bulgaria (72.7%), Latvia (71.4%), and Croatia (80%).

To test these associations, Spearman’s rank correlation was first calculated between the numerical values of the Global Entrepreneurial Index (GEI) and a binary indicator of whether the firm received financing. The correlation coefficient was ρ = 0.059, indicating a very weak and practically negligible correlation. This result shows that when considering GEI values as continuous, there is no systematic relationship with financing outcomes.

However, when the Innovation Index was categorized into three groups (Low < 40, Medium 40–50, High > 50), the Chi-square test of independence revealed statistically significant results (χ2 = 7.35, df = 2, p = 0.025). This indicates that the likelihood of receiving financing differs significantly depending on the innovative performance group of the country. Specifically, firms from countries with a higher innovation index were more likely to secure financing compared to those from countries with medium or lower innovation performance.

Figure 4 illustrates the share of companies that received alternative financing methods. When examining individual countries, clear differences emerge in financing access. Slovenia (GEI rank 25) and Poland (GEI rank 30), both high performers on the Global Entrepreneurship Index, reported that all surveyed firms obtained financing (100%), aligning with the expectation that stronger entrepreneurial ecosystems facilitate access to funding. A similar outcome is observed in Serbia (GEI rank 74) and Montenegro (GEI rank 60), where all firms also secured financing despite weaker GEI performance. This highlights the role of targeted national support schemes that can offset structural deficiencies. In contrast, Greece (GEI rank 48) and Romania (GEI rank 46) show markedly lower access, with only 50% of firms reporting successful financing. These results suggest that even countries with moderate GEI rankings may face institutional or systemic barriers that limit entrepreneurs’ ability to leverage available instruments. Intermediate cases include Bulgaria (GEI rank 69) and Latvia (GEI rank 44), where roughly three-quarters of firms received financing (72.7% and 71.4%, respectively). Finally, Cyprus (GEI rank 32) and Croatia (GEI rank 54) reported relatively high levels of access (83.3% and 80%), though their GEI positions differ substantially.

Figure 4 indicates that nations with stronger entrepreneurial ecosystems generally have greater access to financing, even though targeted national programs, such as those in Serbia and Montenegro, can mitigate lower GEI performance and ensure comparable funding outcomes. Taken together, these results provide only partial support for H3. While the continuous correlation between GEI and financing is negligible, categorical analysis reveals significant cross-country differences. This suggests that entrepreneurial performance influences access to financing, but the effect becomes visible mainly when comparing groups of countries rather than treating GEI as a linear scale.

The following

Table 1 provides a concise summary of all tested hypotheses to facilitate a clearer overview of the applied methods, key statistics, and final decisions.

Robustness Analysis

To ensure that the results are not driven by specific model settings, a robustness check was conducted. The regression model was re-estimated using alternative specifications, including and excluding selected control variables such as firm age, size, and country dummies. The direction, magnitude, and statistical significance of the coefficients related to alternative financing mechanisms remained consistent across specifications. These findings confirm that the identified relationships are robust and not a mere coincidence of the initial variable selection. This reinforces the reliability of empirical evidence and strengthens confidence in the study’s conclusions.

6. Discussion

This study sets out to examine how alternative financing mechanisms support the development and improvement of entrepreneurial ventures and SMEs in selected Widening countries.

It contributes to the literature by providing one of the first multi-country analyses exploring the joint effects of grants, venture capital, business angels, and crowdfunding on firm performance and business model adaptation.

Overall, the results support H1, showing that companies benefiting from alternative financing instruments improved in terms of development stage, revenues, employees, and customer base compared to the period before financing (

Christian Korunka et al., 2011;

Gilbert et al., 2006). As noted by

Howell (

2017), such sources of financing contribute to higher survival rates and the growth of startups, which is consistent with the findings of this study.

The results for H2 provide only partial support. While descriptive evidence indicates that firms which adapted their revenue models after receiving alternative financing tended to move into higher revenue categories over time, statistical tests did not confirm a significant association. This suggests that business model adaptation may enhance financial performance, but the effect is not universal and appears to depend on country-specific and sectoral conditions. The results for H2 indicate that the effect of business model adaptation on revenue performance is not uniform across countries. While firms in Romania, Greece, and Serbia that changed their revenue model consistently reached higher revenue categories, in Bulgaria and Croatia the opposite pattern emerged, and in Latvia even firms without adaptation achieved comparatively strong outcomes, confirming that the link between business model change and financial results is strongly context dependent.

The findings related to H3 are also nuanced. While some countries, such as Poland and Cyprus, clearly follow the expected pattern between GEI rank and access to financing, others such as Slovenia, Serbia, and Montenegro display similar levels of financing despite divergent GEI profiles. Moreover, countries such as Greece and Romania reveal restricted access to funding, suggesting the presence of institutional or structural barriers not captured by GEI rankings. These findings indicate that while the Global Entrepreneurship Index provides a useful context for understanding cross-country differences, it cannot fully explain financing outcomes.

These findings underline that the effect of business model change on revenue outcomes is strongly context-dependent and varies across national ecosystems. The literature emphasizes that business model innovation can significantly increase return on investment and accelerate the growth of companies (

Djuraeva, 2021;

García-Gutiérrez & Martínez-Borreguero, 2016).

Comberg et al. (

2014) further highlight that financial resources play a crucial role in enabling business model pivoting, a finding that is partially confirmed in this study. The findings show that the impact of business model adaptation on revenues is not uniform, as institutional and policy contexts influence how financing translates into performance outcomes.

This aligns with previous studies suggesting that countries with more stable markets and better access to financing are more likely to stimulate business creation. Consequently, early-stage financial support increases the chances of firms obtaining additional funding and evolving into successful enterprises (

Howell, 2017;

Klein et al., 2019;

Saoula et al., 2025). Overall, the study confirms that even among countries with comparable levels of economic development, institutional and policy differences shape the effectiveness of financing instruments and their impact on entrepreneurial outcomes. This implies that policies should be tailored to national contexts rather than assuming homogeneous effects across Widening countries.

The stronger impact of grants compared to venture capital in Widening countries can be explained by the institutional characteristics of these ecosystems. In many of these economies, venture capital markets remain underdeveloped, with a limited number of active funds and a high degree of investor risk aversion. As a result, startups often rely on public or EU-funded grant programs, which provide non-dilutive capital and require less stringent due diligence procedures. Moreover, grants are frequently accompanied by mentoring and post-investment support, which further enhance their effectiveness. By contrast, venture capital in Widening countries tends to concentrate on later-stage firms or specific technology sectors, reducing accessibility for early-stage innovative SMEs. These contextual factors help explain why grants demonstrate a higher post-financing impact in the sample surveyed.

6.1. Practical Implications

These findings offer a concrete roadmap for policymakers to redesign national funding frameworks, prioritize post-investment monitoring, and channel financial resources toward mechanisms that demonstrably enhance startup performance and innovation capacity in Widening countries.

The findings demonstrate that grants play a particularly strong role in enhancing early-stage development and innovation among SMEs in Widening countries. This is primarily due to underdeveloped venture capital markets, investor risk aversion, and the prevalence of accessible public and EU-funded schemes. Policymakers should therefore prioritize hybrid funding models that combine grants with mentorship, post-investment support, and gradual transition toward private financing. Strengthening venture capital ecosystems through tax incentives, co-investment programs, and investor education could further improve market maturity and balance the dominance of public funding.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations. The sample size of 81 companies, though informative, is relatively small and unevenly distributed across countries. The data are self-reported, which may introduce bias, and the analysis covers only a short period without longitudinal tracking. In addition, firms from different sectors were included, which may affect comparability of results.

Future research should expand the sample and employ longitudinal data to capture longer-term effects of financing. Sector-specific studies and mixed-method approaches, combining surveys with case studies or secondary financial data, could provide deeper insights into how financing mechanisms influence entrepreneurial outcomes in different institutional contexts.

7. Conclusions

This study advances the understanding of how alternative financing mechanisms influence the transformation of entrepreneurial intention into action in Widening countries. It shows that access to external funding, particularly through grants, business angels, crowdfunding, and venture capital, acts as a critical enabler that converts entrepreneurial potential into tangible outcomes. By linking financial mechanisms to institutional maturity, the findings highlight that even among economies with similar levels of development, contextual differences in policy and ecosystem structure determine the effectiveness of financing instruments and their contribution to business growth.

The study extends existing models of entrepreneurial dynamics by demonstrating that financial and institutional readiness jointly determine whether entrepreneurial potential materializes into sustainable firm development. It bridges intention-based theories of entrepreneurship with post-investment performance outcomes, thereby providing a more comprehensive view of the entrepreneurial process in transitional economies.

For policymakers, the results emphasize that one-size-fits-all approaches are ineffective. Tailored national policies should strengthen early-stage grant mechanisms while simultaneously nurturing venture capital ecosystems through tax incentives, co-investment schemes, and investor education. Supporting hybrid models that combine non-dilutive funding with mentoring and post-investment monitoring can further accelerate firm growth and innovation capacity.

Future research should expand the sample and employ longitudinal data to capture longer-term effects of financing. Comparative studies involving non-EU developing countries could further illuminate how institutional maturity moderates the relationship between financing mechanisms and entrepreneurial outcomes. Qualitative case studies would also provide a deeper understanding of post-investment effects and contextual influences within Widening innovative ecosystems.