Destination Evaluation Attributes for Tourists in Hotel and Non-Hotel Accommodation in Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Overnight Tourists

2.2. Hotel and Non-Hotel Accommodation

2.3. Destination Evaluation Attributes

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Research Scenario

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Assessment of Destination Attributes

4.2. Assessment of Destination Attributes by Type of Accommodation

4.2.1. Hotel Category

4.2.2. Non-Hotel Category

4.3. Independent Samples t-Test: Hotel Accommodation vs. Non-Hotel Accommodation

4.4. Neural Network Analysis

4.4.1. Neural Network Analysis at a Global Level

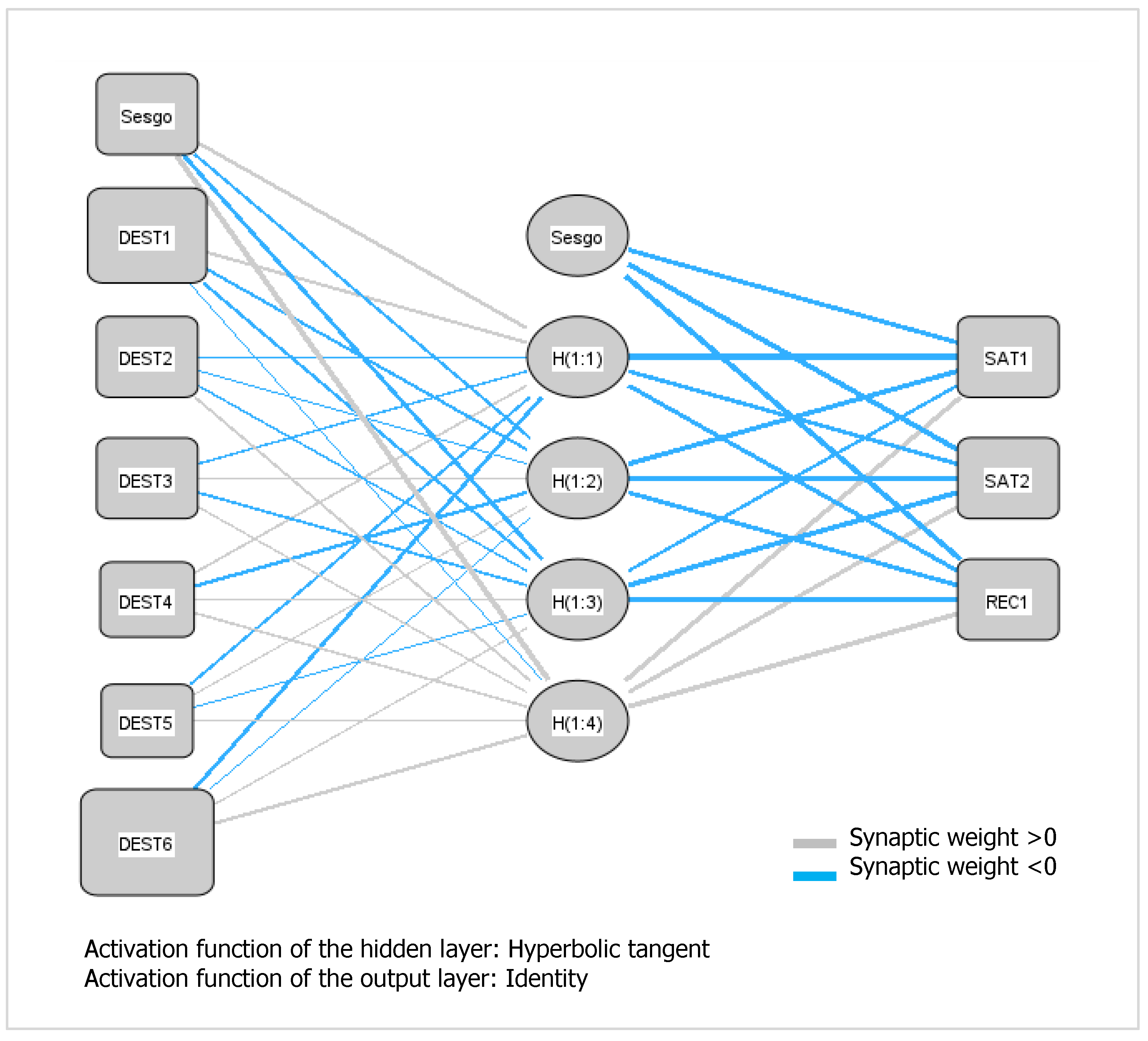

4.4.2. Neural Network Analysis for Hotel Category

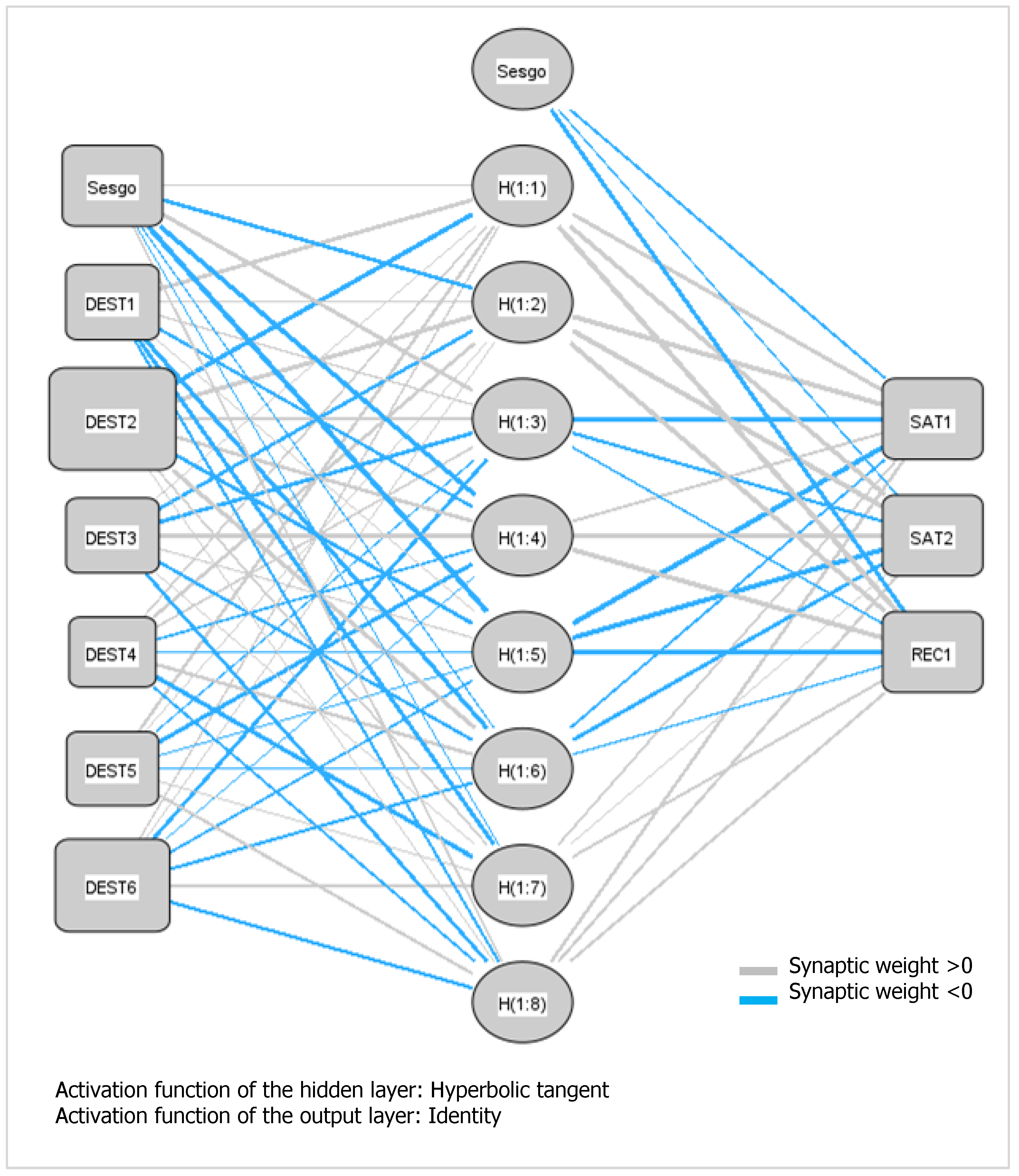

4.4.3. Neural Network Analysis for Non-Hotel Category

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

This research has been co-funded by the European Social Fund (ESF+) and Junta de Extremadura within the framework of “Individual Research Grant for the Recruitment of Pre-doctoral Research Staff in Training within the Extremadura Science, Technology and Innovation System (SECTI)” (Reference No. PD 23012).

This research has been co-funded by the European Social Fund (ESF+) and Junta de Extremadura within the framework of “Individual Research Grant for the Recruitment of Pre-doctoral Research Staff in Training within the Extremadura Science, Technology and Innovation System (SECTI)” (Reference No. PD 23012).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DMO | Destination Management Organizations |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technologies |

| INE | Instituto Nacional de Estadística (Spanish Statistical Office) |

References

- Alegre, J., & Garau, J. (2010). Tourist satisfaction and dissatisfaction. Annals of Tourism Research, 37, 52–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaya-Molinar, C. M., Sosa-Ferreira, A. P., Ochoa-Llamas, I., & Moncada Jiménez, P. (2017). The perception of destination competitiveness by tourists. Investigaciones Turísticas, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atsız, O., & Akova, M. (2021). Cultural destination attributes, overall tourist satisfaction and tourist loyalty: First timers versus repeaters. Advances in Hospitality and Tourism Research, 9(2), 268–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badoni, M., Rawat, B., & Aggarwal, M. (2025). Socio-demographic analysis of destination selection factors for Himalayan hill destinations. F1000Research, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, M., & Wicherts, J. M. (2014). Outlier removal, sum scores, and the inflation of the type I error rate in independent samples t tests: The power of alternatives and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 19(3), 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera-Martínez, A. M., Santana-Talavera, A., & Parra-López, E. (2025). Destination competitiveness through the lens of tourist spending: A case study of the Canary Islands. Sustainability, 17(7), 3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichler, B., Pikkemaat, B., & Peters, M. (2021). Exploring the role of service quality, atmosphere and food for revisits in restaurants by using an e-mystery guest approach. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 4(3), 351–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braimah, S. M., Solomon, E. N.-A., & Hinson, R. E. (2024). Tourists satisfaction in destination selection determinants and revisit intentions: Perspectives from Ghana. Cogent Social Sciences, 10, 2318864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celotto, E., Ellero, A., & Ferretti, P. (2015). Conveying tourist ratings into an overall destination evaluation. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 188, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chen, C. M., Chen, S. H., Lee, H. T., & Tsai, T. H. (2016). Exploring destination resources and competitiveness—A comparative analysis of tourists’ perceptions and satisfaction toward an island of Taiwan. Ocean & Coastal Management, 119, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheraghzadeh, M., Rahimian, M., & Gholamrezai, S. (2024). Effective factors on tourist satisfaction with the quality of ecotourism destinations (Case study: Bisheh waterfall in Lorestan province, Iran). Environment, Development and Sustainability, 26, 28699–28726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croes, H. (2008). Accommodation portfolio and market differentiation: The case of Aruba. Tourism, 56(2), 185–197. [Google Scholar]

- Dann, G. M. (1981). Tourism motivations: An appraisal. Annals of Tourism Research, 8, 187–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davras, Ö., & Özperçin, İ. (2021). The relationships of motivation, service quality, and behavioral intentions for gastronomy festival: The mediating role of destination image. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure & Events, 15(4), 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A., Sarstedt, M., Fuchs, C., Wilczynski, P., & Kaiser, S. (2012). Guidelines for choosing between multi-item and single-item scales for construct measurement: A predictive validity perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 434–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrovski, D. (2016). Urban gastronomic festivals—Non-food related attributes and food quality in satisfaction construct: A pilot study. Journal of Convention & Event Tourism, 17(4), 247–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escandón-Barbosa, D., & Hurtado-Ayala, A. (2014). Los determinantes de la orientación exportadora y los resultados en las pymes exportadoras en Colombia. Estudios Gerenciales, 30(133), 430–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. (2023a). Arrivals of residents/non-residents at tourist accommodation establishments. Annual data on tourism industries. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tin00174/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Eurostat. (2023b). Nights spent at tourist accommodation establishments by residents/non-residents. Annual data on tourism industries. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tin00175/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Eusébio, C., & Vieira, A. L. (2013). Destination attributes’ evaluation, satisfaction and behavioural intentions: A structural modelling approach. International Journal of Tourism Research, 15, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallon, P., & Schofield, P. (2006). The dynamics of destination attribute importance. Journal of Business Research, 59, 709–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, M., Höpken, W., & Lexhagen, M. (2014). Big data analytics for knowledge generation in tourism destinations—A case from Sweden. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 3(4), 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Diaz, B., Gomez, M., & Molina, A. (2015). Configuration of the hotel and non-hotel accommodations: An empirical approach using network analysis. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 48, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J., & Jang, S. (2010). Effects of service quality and food quality: The moderating role of atmospherics in an ethnic restaurant segment. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 29(3), 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höpken, W., Fuchs, M., & Lexhagen, M. (2018). Big data analytics for tourism destinations. In M. Khosrow-Pour (Ed.), Advanced methodologies and technologies in network architecture, mobile computing, and data analytics (4th ed., pp. 28–45). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INE. (2025a). Estancia media de los viajeros por residencia y categoría. Alojamientos de turismo rural: Encuesta de ocupación e índice de precios. Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxi/Datos.htm?tpx=68574#_tabs-tabla (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- INE. (2025b). Estancia media de los viajeros por residencia y categoría. Hoteles: Encuesta de ocupación, índice de precios e indicadores de rentabilidad. Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxi/Datos.htm?tpx=69885#_tabs-grafico (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- International Business Machines. (2019). IBM SPSS neural networks 26. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/SSLVMB_26.0.0/pdf/en/IBM_SPSS_Neural_Network.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Jumanazarov, S., Kamilov, A., & Kiatkawsin, K. (2020). Impact of Samarkand’s destination attributes on international tourists’ revisit and word-of-mouth intention. Sustainability, 12, 5154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T., Han, S., & Park, J. H. (2022). What drives long-stay tourists to revisit destinations? A case study of Jeju Island. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 27(8), 856–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, E., & Chun-Der, C. (2024). Artificial intelligence innovation of tourism businesses: From satisfied tourists to continued service usage intention. International Journal of Information Management, 76, 102757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalicic, L., Marine-Roig, E., Ferrer-Rosell, B., & Martin-Fuentes, E. (2021). Destination image analytics for tourism design: An approach through Airbnb reviews. Annals of Tourism Research, 86, 103100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Xu, L., Tang, L., Wang, S., & Li, L. (2018). Big data in tourism research: A literature review. Tourism Management, 68, 301–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y. C., Tsai, H. Y. M., Liang, A. R. D., & Chang, H. Y. (2024). Role of destination attachment in accommodation experiences of historical guesthouses. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 24(1), 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B., Prideaux, B., & Thompson, M. (2023). The relationship between accommodation type and tourists’ in-destination behaviour. Tourism Recreation Research, 50(1), 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsalve-Castro, C., & Hernández-Rueda, S. I. (2015). Gestión de la calidad del servicio en la hotelería como elemento clave en el desarrollo de destinos turísticos sostenibles: Caso Bucaramanga. Revista EAN, 78, 160–173. [Google Scholar]

- Muskat, B., Hörtnagl, T., Prayag, G., & Wagner, S. (2019). Perceived quality, authenticity, and price in tourists’ dining experiences: Testing competing models of satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 25(4), 480–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussalam, G. Q., & Tajeddini, K. (2016). Tourism in Switzerland: How perceptions of place attributes for short and long holiday can influence destination choice. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 26, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutinda, R., & Mayaka, M. (2012). Application of destination choice model: Factors influencing domestic tourists’ destination choice among residents of Nairobi, Kenya. Tourism Management, 33, 1593–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, D. (2015). Tourist resources and tourist attractions: Conceptualization, classification and assessment. Cuadernos de Turismo, 35, 481–484. [Google Scholar]

- Nield, K., Kozak, M., & LeGrys, G. (2000). The role of food service in tourist satisfaction. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 19(4), 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J. Y., & Schuett, M. A. (2010). Exploring expenditure-based segmentation for rural tourism: Overnight stay visitors versus excursionists to fee-fishing sites. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 27(1), 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R. L., & Swan, J. E. (1989). Consumer perceptions of interpersonal equity and satisfaction in transactions: A field survey approach. Journal of Marketing, 53(2), 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omo-Obas, P., & Anning-Dorson, T. (2023). Cognitive-affective-motivation factors influencing international visitors’ destination satisfaction and loyalty. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Insights, 6(5), 2222–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, N. M., Ribeiro, M. A., & Prayag, G. (2023). Psychological determinants of tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: The influence of perceived overcrowding and overtourism. Journal of Travel Research, 62, 644–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pestana, M. H., Parreira, A., & Moutinho, L. (2020). Motivations, emotions and satisfaction: The keys to a tourism destination choice. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 16, 100332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Fernández, J. I., Casado-Montilla, J., Carrillo-Hidalgo, I., & Durán-Román, J. L. (2024). Does type of accommodation influence tourist behavior? Hotel accommodation vs. rural accommodation. Anatolia, 35(2), 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radojevic, T., Stanisic, N., Stanic, N., & Davidson, R. (2018). The effects of traveling for business on customer satisfaction with hotel services. Tourism Management, 67, 326–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rašovská, I., Kubickova, M., & Ryglová, K. (2021). Importance–performance analysis approach to destination management. Tourism Economics, 27(4), 777–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J. R., Crouch, G. I., & Hudson, S. (2000). Assessing the role of consumers in the measurement of destination competitiveness and sustainability. Tourism Analysis, 5(2–3), 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Rochon, J., Gondan, M., & Kieser, M. (2012). To test or not to test: Preliminary assessment of normality when comparing two independent samples. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 12(81), 1471–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romão, J., Neuts, B., Nijkamp, P., & Shikida, A. (2014). Determinants of trip choice, satisfaction and loyalty in an eco-tourism destination: A modelling study on the Shiretoko Peninsula, Japan. Ecological Economics, 107, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoso, H. B., Wang, J. C., & Windasari, N. A. (2022). Impact of multisensory extended reality on tourism experience journey. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 13(3), 356–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, P., Coromina, L., Camprubi, R., & Kim, S. (2020). An analysis of first-time and repeat-visitor destination images through the prism of the three-factor theory of consumer satisfaction. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 17, 100463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzadi, M., Malik, S. A., Ahmad, M., & Shabbir, A. (2018). Perceptions of fine dining restaurants in Pakistan: What influences customer satisfaction and behavioral intentions? International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 35(3), 635–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B., Ao, C., Wang, J., Mao, B., & Xu, L. (2020). Listen to the voices from tourists: Evaluation of wetland ecotourism satisfaction using an online reviews mining approach. Wetlands, 40, 1379–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štumpf, P., Janeček, P., & Vojtko, V. (2022). Is visitor satisfaction high enough? A case of rural tourism destination, South Bohemia. European Countryside, 14(2), 346–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travar, I., Todorović, N., Pavlović, S., & Parra-López, E. (2022). Are image and quality of tourist services strategic determinants of satisfaction? Millennials’ perspective in emerging destinations. Administrative Sciences, 12, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I. P., & Pesonen, J. (2016). Impacts of peer-to-peer accommodation use on travel patterns. Journal of Travel Research, 55(8), 1022–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Tourism. (2025). Glossary of tourism terms. UNWTO. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/glossary-tourism-terms#H (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Veloso, M., & Gómez-Suárez, M. (2023). Customer experience in the hotel industry: A systematic literature review and research agenda. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 35(8), 3006–3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, J., & Salam, A. (2019). Testing statistical assumptions in research (1st ed.). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Vojtko, V., Štumpf, P., Rašovská, I., McGrath, R., & Ryglová, K. (2022). Removing uncontrollable factors in benchmarking tourism destination satisfaction. Journal of Travel Research, 61(1), 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J., Hong, Q., Cao, M., Liu, Y., & Fujita, H. (2022). A group consensus-based travel destination evaluation method with online reviews. Applied Intelligence, 52, 1306–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y., Zhang, Z., Fong, D. K. C., & Law, R. (2018). Can staying overnight affect traveler satisfaction? Evidence from a gambling destination. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 23(9), 907–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, A., Yuksel, F., & Bilim, Y. (2010). Destination attachment: Effects on customer satisfaction and cognitive, affective and conative loyalty. Tourism Management, 31(2), 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulvianti, N., Aimon, H., & Abror, A. (2022). The influence of environmental and non-environmental factors on tourist satisfaction in halal tourism destinations in West Sumatra, Indonesia. Sustainability, 14, 9185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item Code | Construct | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| [DEST_1] | Tourism resources of the area (Alegre & Garau, 2010; Eusébio & Vieira, 2013; Mussalam & Tajeddini, 2016; Travar et al., 2022; Štumpf et al., 2022) | All natural or cultural elements available in a given destination. |

| [DEST_2] | Adequacy of tourism resources (Fallon & Schofield, 2006; Jumanazarov et al., 2020; Eusébio & Vieira, 2013; Celotto et al., 2015; Mussalam & Tajeddini, 2016; Schofield et al., 2020; Omo-Obas & Anning-Dorson, 2023) | Implementation of infrastructures, facilities, equipment, accessibility elements, and signage that enable their use by visitors. |

| [DEST_3] | Possibility of engaging in activities (Mutinda & Mayaka, 2012; Jumanazarov et al., 2020; Schofield et al., 2020; Travar et al., 2022; Štumpf et al., 2022) | The extent to which tourists perceive the existence and accessibility of tourism-related experiences and activities at the destination. |

| [DEST_4] | Tourism information services (Mussalam & Tajeddini, 2016; Romão et al., 2014; Jumanazarov et al., 2020; Štumpf et al., 2022) | Set of resources and tools designed to assist, inform, and provide guidance to tourists regarding the destination’s offerings. |

| [DEST_5] | Quantity of food service provision (Fallon & Schofield, 2006; Celotto et al., 2015; Jumanazarov et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2022) | The number of establishments and facilities providing gastronomic and beverage offerings in the destination. |

| [DEST_6] | Quality of food service provision (Eusébio & Vieira, 2013; Mussalam & Tajeddini, 2016; Jumanazarov et al., 2020; Schofield et al., 2020; Travar et al., 2022; Zulvianti et al., 2022) | The perceived quality of establishments and facilities offering gastronomy and beverages at the destination. |

| [DEST_7] | Overall assessment of services (Eusébio & Vieira, 2013; Jumanazarov et al., 2020; Atsız & Akova, 2021; Štumpf et al., 2022; Papadopoulou et al., 2023; Omo-Obas & Anning-Dorson, 2023; Braimah et al., 2024) | Visitor’s assessment by comparing prior expectations with the experience at the destination, integrating both rational evaluations of attributes and emotional responses (Lalicic et al., 2021). |

| [DEST_8] | Overall assessment of the area (Eusébio & Vieira, 2013; Mussalam & Tajeddini, 2016; Schofield et al., 2020; Papadopoulou et al., 2023; Badoni et al., 2025) | The general assessment of the destination, considering its overall offer and evaluation of attributes. |

| [DEST_9] | Willingness to recommend to a friend (Eusébio & Vieira, 2013; Mussalam & Tajeddini, 2016; Jumanazarov et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2020; Papadopoulou et al., 2023) | The traveller’s intention to recommend the destination to friends, relatives, and other potential tourists. |

| Accommodation Typology | Number | Bedplaces | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hotel accommodation (rural and urban) | 12,798 | 1,163,339 | |

| Non-hotel accommodation | Camp sites | 522 | 272,705 |

| Hostels | 1203 | 69,269 | |

| Tourist apartments | 6178 | 421,474 | |

| Rural tourism accommodations | 15,482 | 140,359 | |

| All typologies | 23,363 | 903,807 | |

| Destination Attributes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | M |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tourism resources of the area | 0.5 | 1.0 | 6.6 | 28.8 | 63.2 | 4.53 |

| Adequacy of tourism resources | 5.0 | 1.2 | 8.4 | 33.2 | 56.8 | 4.45 |

| Possibility of engaging in activities | 6.0 | 1.4 | 9.2 | 29.9 | 59.0 | 4.45 |

| Tourism information services | 1.1 | 2.5 | 13.6 | 31.1 | 51.7 | 4.30 |

| Quantity of food service provision | 1.5 | 2.8 | 11.7 | 29.4 | 54.7 | 4.33 |

| Quality of food service provision | 1.3 | 2.1 | 10.5 | 30.8 | 55.4 | 4.37 |

| Marketing Results | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | M |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall assessment of services | 0.6 | 1.3 | 7.5 | 33.2 | 57.4 | 4.46 |

| Overall assessment of the area | 0.4 | 0.9 | 5.7 | 29.6 | 63.4 | 4.55 |

| Willingness to recommend to a friend | 1.1 | 1.1 | 4.0 | 21.9 | 71.8 | 4.62 |

| Destination Attributes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | M |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tourism resources of the area | 0.5 | 1.2 | 7.1 | 29.6 | 61.5 | 4.50 |

| Adequacy of tourism resources | 0.5 | 1.4 | 9.4 | 34.0 | 54.7 | 4.41 |

| Possibility of engaging in activities | 0.6 | 1.5 | 10.4 | 31.2 | 56.3 | 4.41 |

| Tourism information services | 1.1 | 2.7 | 14.5 | 32.0 | 49.7 | 4.26 |

| Quantity of food service provision | 1.4 | 2.8 | 11.3 | 29.8 | 54.7 | 4.34 |

| Quality of food service provision | 1.2 | 2.2 | 10.6 | 31.2 | 54.7 | 4.36 |

| Marketing Results | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | M |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall assessment of services | 0.6 | 1.4 | 8.0 | 34.1 | 55.9 | 4.43 |

| Overall assessment of the area | 0.4 | 1.0 | 6.6 | 31.0 | 61.1 | 4.51 |

| Willingness to recommend to a friend | 1.2 | 1.2 | 4.8 | 23.6 | 69.3 | 4.59 |

| Destination Attributes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | M |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tourism resources of the area | 0.4 | 0.8 | 6.0 | 28.0 | 64.8 | 4.56 |

| Adequacy of tourism resources | 0.4 | 1.0 | 7.4 | 32.3 | 58.9 | 4.48 |

| Possibility of engaging in activities | 0.5 | 1.2 | 8.1 | 28.5 | 61.7 | 4.50 |

| Tourism information services | 1.1 | 2.3 | 12.7 | 30.2 | 53.7 | 4.33 |

| Quantity of food service provision | 1.5 | 2.9 | 12.0 | 28.9 | 54.6 | 4.32 |

| Quality of food service provision | 1.4 | 1.9 | 10.4 | 30.3 | 56.0 | 4.38 |

| Marketing Results | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | M |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall assessment of services | 0.6 | 1.2 | 7.0 | 32.2 | 59.0 | 4.48 |

| Overall assessment of the area | 0.3 | 0.7 | 4.9 | 28.2 | 65.8 | 4.58 |

| Willingness to recommend to a friend | 1.0 | 1.0 | 3.3 | 20.3 | 74.4 | 4.66 |

| Hotel Category | Non-Hotel Category | Confidence Interval | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Destination attributes | ||||||

| DEST_1 | 4.50 | 0.729 | 4.56 | 0.679 | [−0.070; −0.045] | <0.001 *** |

| DEST_2 | 4.41 | 0.759 | 4.48 | 0.711 | [−0.087; −0.060] | <0.001 *** |

| DEST_3 | 4.41 | 0.785 | 4.5 | 0.740 | [−0.100; −0.072] | <0.001 *** |

| DEST_4 | 4.26 | 0.885 | 4.33 | 0.865 | [−0.082; −0.050] | <0.001 *** |

| DEST_5 | 4.34 | 0.885 | 4.32 | 0.902 | [−0.003; 0.030] | 0.111 ns |

| DEST_6 | 4.36 | 0.848 | 4.38 | 0.850 | [−0.031; 0.000] | 0.056 ns |

| Marketing results | ||||||

| SAT_1 | 4.43 | 0.750 | 4.48 | 0.728 | [−0.060; −0.034] | <0.001 *** |

| SAT_2 | 4.51 | 0.698 | 4.58 | 0.653 | [−0.083; −0.058] | <0.001 *** |

| REC_1 | 4.59 | 0.741 | 4.66 | 0.685 | [−0.088; −0.063] | <0.001 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sánchez-Vargas, E.; López-Salas, S.; Pasaco-González, B.-S.; Moreno-Lobato, A. Destination Evaluation Attributes for Tourists in Hotel and Non-Hotel Accommodation in Spain. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 418. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110418

Sánchez-Vargas E, López-Salas S, Pasaco-González B-S, Moreno-Lobato A. Destination Evaluation Attributes for Tourists in Hotel and Non-Hotel Accommodation in Spain. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(11):418. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110418

Chicago/Turabian StyleSánchez-Vargas, Elena, Sergio López-Salas, Bárbara-Sofía Pasaco-González, and Ana Moreno-Lobato. 2025. "Destination Evaluation Attributes for Tourists in Hotel and Non-Hotel Accommodation in Spain" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 11: 418. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110418

APA StyleSánchez-Vargas, E., López-Salas, S., Pasaco-González, B.-S., & Moreno-Lobato, A. (2025). Destination Evaluation Attributes for Tourists in Hotel and Non-Hotel Accommodation in Spain. Administrative Sciences, 15(11), 418. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110418