1. Introduction

In recent years, growing attention from entrepreneurship scholars and practitioners has been directed toward understanding how individuals navigate the path to entrepreneurial careers (

Dong et al., 2020;

Fatoki, 2020). This interest is largely driven by the widespread recognition of entrepreneurship as a key engine for job creation, innovation, and broader economic and social advancement (

Karimi et al., 2014). In light of persistent challenges such as unemployment, poverty, and inequality, research on entrepreneurial intention (EI) has become crucial for uncovering how individuals develop entrepreneurial aspirations, how new ventures are formed, and what factors influence this process (

Krueger et al., 2000;

Malebana, 2014). These insights are essential for informing targeted strategies and policies that foster and support entrepreneurial activity, particularly in developing countries (

Ndofirepi, 2020;

Nergui, 2020).

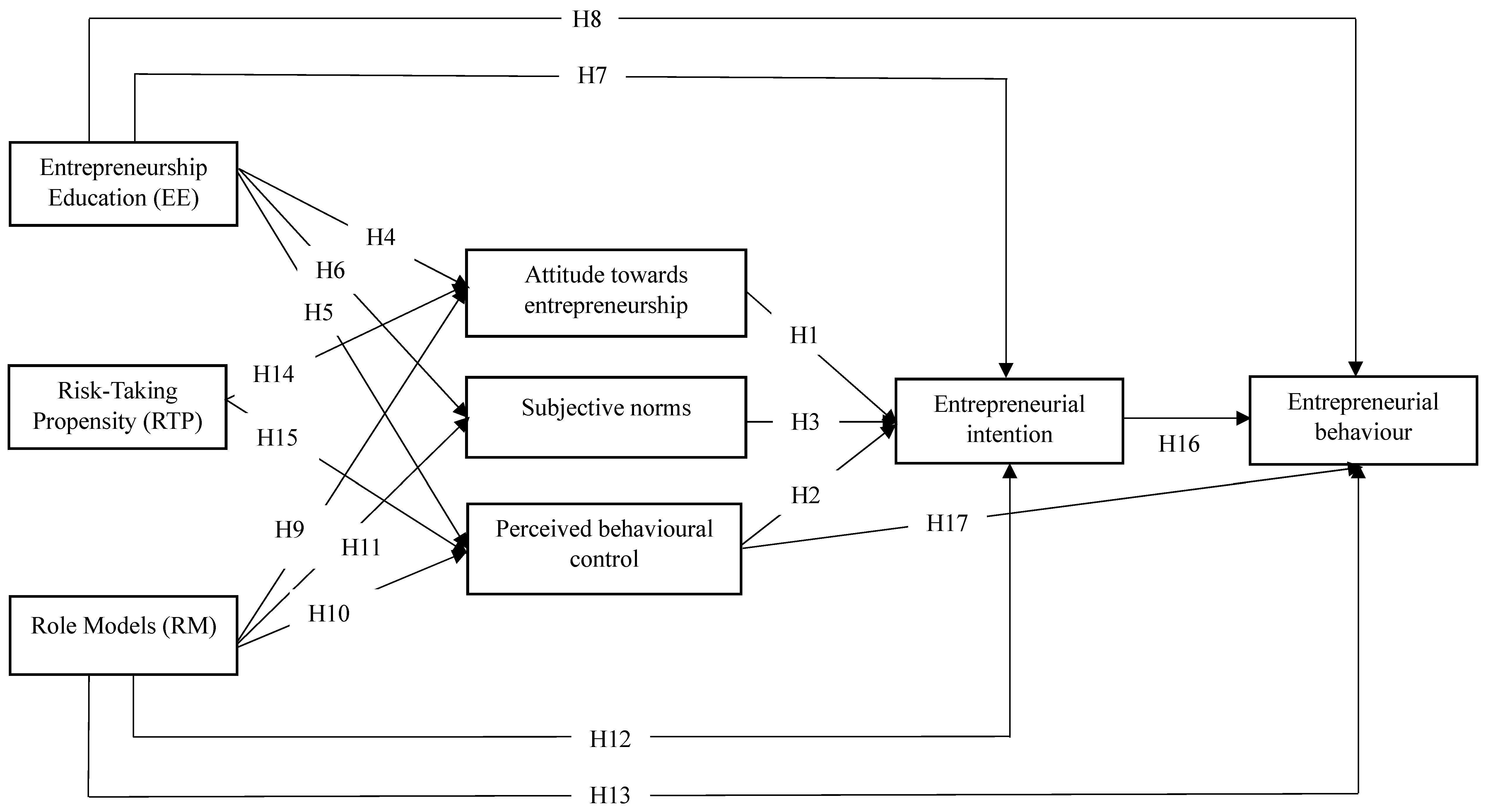

Despite the widely acknowledged benefits of entrepreneurship, limited understanding remains regarding the factors shaping EI and subsequent behaviour, particularly among students, a youth demographic often exposed to high levels of unemployment. To fill this gap in the literature, this study examines the influence of entrepreneurship education (EE) and role models (RMs) on the antecedents of EI, EI, and subsequent entrepreneurial behaviour (EB) among university and Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) college students, drawing from the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB). The study further investigates the impact of risk-taking propensity (RTP) on attitude toward behaviour (ATB) and perceived behavioural control (PBC) and explores the direct effects of EI and PBC on EB.

The South African context makes this investigation particularly urgent. Youth unemployment in South Africa remains a pressing challenge, with rates reaching 59.6% among those aged 15–24 and 40.5% among those aged 25–34 (

Statistics South Africa, 2025). Alarmingly, even individuals with vocational qualifications and university degrees face significant unemployment rates of 37.3% and 23.9%, respectively (

Statistics South Africa, 2025). These figures strongly underscore the urgency of the study and the need to promote entrepreneurship as a viable career pathway for graduates. They also signal an immediate need for policy intervention and highlight the responsibility of higher education institutions to implement strategies that promote entrepreneurship as a viable and appealing career option (

Mothibi & Malebana, 2019;

Wijayanti & Noviani, 2025). University and vocational graduates, in particular, have the potential to drive job creation through entrepreneurial ventures and should be encouraged to see themselves as potential employers rather than mere job seekers (

Maulida et al., 2024;

Wijayanti & Noviani, 2025). Strengthening EE and support can cultivate EI and better equip individuals to establish and sustain their own businesses (

Maulida et al., 2024).

Prior research has consistently highlighted the role of EE in shaping entrepreneurial outcomes. EE provides students with the skills and knowledge critical to undertaking entrepreneurial careers (

Hassan et al., 2020;

Otache, 2019), fostering entrepreneurial thinking and preparing them for future business ventures (

Sorakraikitikul et al., 2024). EE has also been shown to enhance entrepreneurial attitudes (

Ndofirepi & Rambe, 2017), strengthen self-efficacy perceptions (

Liñán et al., 2013), foster RTP (

Yasin & Khansari, 2021), and positively influence EI (

Ferdousi et al., 2025). EE also contributes towards the development of the capacity to identify and act on entrepreneurial opportunities through the generation of new ideas and the mobilisation of necessary resources (

Al-Omar et al., 2024;

Lavelle, 2019). Given the crucial role of EE in assisting graduates to transition into entrepreneurship by transforming intentions into actual business ventures (

Ferdousi et al., 2025), further research is needed to deepen understanding of its effects on the antecedents of EI, EI itself, and subsequent EB. Such insights could inform more targeted and evidence-based policy interventions aimed at stimulating entrepreneurial activity. Extensive reviews by

Mahlaole and Malebana (

2021) and

Mothibi et al. (

2024) highlight inconsistent and mixed findings regarding the effects of EE on both EI and its antecedents, which varied between gender, duration of the programme and sample studied. Additionally, while most of prior research has either tested the impact of EE on the antecedents of EI or EI itself, little research, if any exists, examined the effects of EE on both the antecedents of EI, EI and EB.

In addition to EE, role models (RMs) play an important role in shaping entrepreneurial aspirations. Previous studies indicate that by observing others and identifying with their actions, individuals learn and develop the capacity to generate ideas about how certain behaviours, such as starting a business, are performed and how they ought to be performed (

Liñán & Santos, 2007;

Peng et al., 2020). In particular, exposure to entrepreneurial RMs empowers students to develop the skills and knowledge required to pursue entrepreneurship (

Moreno-Gómez et al., 2020;

Mothibi, 2018;

Yang, 2017) and enhances the attractiveness and credibility of an entrepreneurial career choice (

Malebana, 2016). While previous research has examined the effect of entrepreneurial role models on the antecedents of EI and on intention itself (

Choukir et al., 2019;

Malebana, 2016;

Mothibi, 2018), considerable variation exists in how these effects are reported across different studies and contexts. It has also been found that not all role models affect EI and its antecedents (

Malebana & Mothibi, 2023;

Malebana, 2016). For example,

Moreno-Gómez et al. (

2020) found that exposure to entrepreneurial role models had a significant positive effect on EI among students, whereas

Efrata et al. (

2021) reported no such effect.

Mothibi et al. (

2024) reported insignificant effects of RMs on both PBC and ATB. Additionally,

Malebana and Mothibi (

2023) observed that family members and friends who run businesses, and knowledge of someone who is an entrepreneur have no influence on EI and its antecedents. There is a lack of studies that test the impact of RMs on both the antecedents of EI, EI and EB using the TPB. These inconsistencies and gaps highlight the need for deeper investigation into the mechanisms through which entrepreneurial RMs shape the antecedents of EI, as well as EI itself and subsequent behaviour.

Entrepreneurship, by definition, involves individuals taking various forms of risk in the exploitation of market opportunities (

Anwar & Saleem, 2019). Accordingly, RTP is widely regarded as a key characteristic that distinguishes entrepreneurs from non-entrepreneurs (

Antoncic et al., 2018;

Keelson et al., 2025). Findings from previous research suggest that individuals with a higher RTP are more likely to develop intentions to become entrepreneurs (

Razak et al., 2020), exhibit a favourable perception of entrepreneurship, and express confidence in their ability to launch a business (

Anwar et al., 2021;

Karimi et al., 2017). In addition, individuals with high RTP are more likely to engage in EB (

Mothibi et al., 2024,

2025). However,

Munir et al. (

2019) reported that risk-taking propensity had an insignificant negative statistical effect on students’ intentions to become business owners. These divergent findings underscore the inconsistency in prior research. While RTP has long been recognised as a central entrepreneurial trait, the specific ways in which it shapes the antecedents of EI remain underexplored, particularly in the context of TVET institutions, more so in a developing country such as South Africa.

This study advances the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) by incorporating EE and entrepreneurial RMs as additional independent variables influencing not only the antecedents of EI but also EI itself and subsequent EB. By doing so, it offers a more nuanced and holistic understanding of the drivers behind EI and actions. Furthermore, existing research has largely concentrated on university students, often overlooking learners in TVET institutions. Given the unique characteristics and needs of this group, addressing this gap is essential. This research adds to existing knowledge by exploring these relationships among both TVET and university students in South Africa, offering new perspectives on the varied pathways leading to entrepreneurial behaviour.

In line with the purpose of this study, the paper is structured as follows. The next section presents a review of the relevant literature and the formulation of research hypotheses, supported by a conceptual model. This is followed by a description of the research methodology, presentation of the results, and a discussion of the key findings. The paper closes with a final section that outlines its key contributions, reflects on its limitations, and identifies potential areas for future investigation.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Evaluation

Data were analysed using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) implemented in SmartPLS 4 (version 4.0.8.3). The analysis began with a thorough evaluation of the measurement model to ensure construct reliability and validity. Reliability was assessed using factor loadings, Cronbach’s alpha, and composite reliability (CR), while convergent validity was established through average variance extracted (AVE). Discriminant validity was confirmed using the Fornell–Larcker criterion, and the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT).

The factor loadings were assessed based on the guideline recommending a minimum acceptable value of 0.50 (

J. F. Hair et al., 2020,

2019). Following the removal of 11 items with insufficient loadings,

Table 2 shows that the remaining items had loadings ranging from 0.570 to 0.885, all exceeding the recommended threshold. These retained indicators exhibited strong loadings on their respective constructs and maintained satisfactory internal consistency.

Construct reliability was further confirmed through Cronbach’s alpha (CRA) and composite reliability (CR). As recommended by

J. F. Hair et al. (

2020), reliability coefficients between 0.70 and 0.90 reflect an acceptable to high level of internal consistency. As presented in

Table 2, all latent constructs achieved Cronbach’s alpha (α) and composite reliability (CR) values exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.70, with CRA ranging from 0.721 to 0.922 and CR ranging from 0.781 to 0.938. These results provide strong evidence of internal consistency among the measurement items, confirming that the constructs were reliably captured by the survey instrument.

Convergent validity was examined using the Average Variance Extracted (AVE), which reflects the extent to which a construct explains the variance of its indicators. As recommended by

Sarstedt et al. (

2017), AVE values of 0.50 or higher indicate adequate convergent validity. As shown in

Table 2, all constructs achieved AVE values above this threshold, ranging from 0.524 to 0.683. These results confirm that each construct sufficiently captures the variance of its associated measurement items, thereby demonstrating satisfactory convergent validity (

J. F. Hair et al., 2020).

Discriminant validity was first assessed using the Fornell-Larcker criterion, which posits that the square root of the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each construct should be greater than its correlations with other constructs (

Fornell & Larcker, 1981). As shown in

Table 3, the square roots of the AVE values are greater than the corresponding inter-construct correlations, confirming that the model meets the criteria for satisfactory discriminant validity.

To further verify discriminant validity, the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio was employed, as recommended by

J. Hair and Alamer (

2022). HTMT is considered a more stringent criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based SEM (

J. Hair & Alamer, 2022).

Table 4 presents the HTMT values for each pair of latent constructs. All HTMT values were below the recommended threshold of 0.85 (

J. Hair & Alamer, 2022), indicating that the constructs are empirically distinct from one another. These findings provide additional confirmation that the measurement model demonstrates satisfactory discriminant validity.

4.2. Structural Model Evaluation

To evaluate the structural model,

J. Hair and Alamer (

2022) recommend examining potential collinearity issues, the coefficient of determination (R

2), path coefficients (β), and their corresponding t-values using a bootstrapping procedure with 5000 resamples. In addition to these fundamental metrics, researchers are also encouraged to report predictive relevance (Q

2) and effect sizes (f

2) to ensure a more comprehensive assessment.

Collinearity issues were assessed using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), with a threshold value of less than 5, as recommended by

Sarstedt et al. (

2017). VIF values exceeding this threshold indicate potential multicollinearity among the constructs. As shown in

Table 2, all VIF values are below the critical threshold of 5, ranging from 1.00 to 4.116. This indicates the absence of multicollinearity in the research model and supports the validity of the indicators.

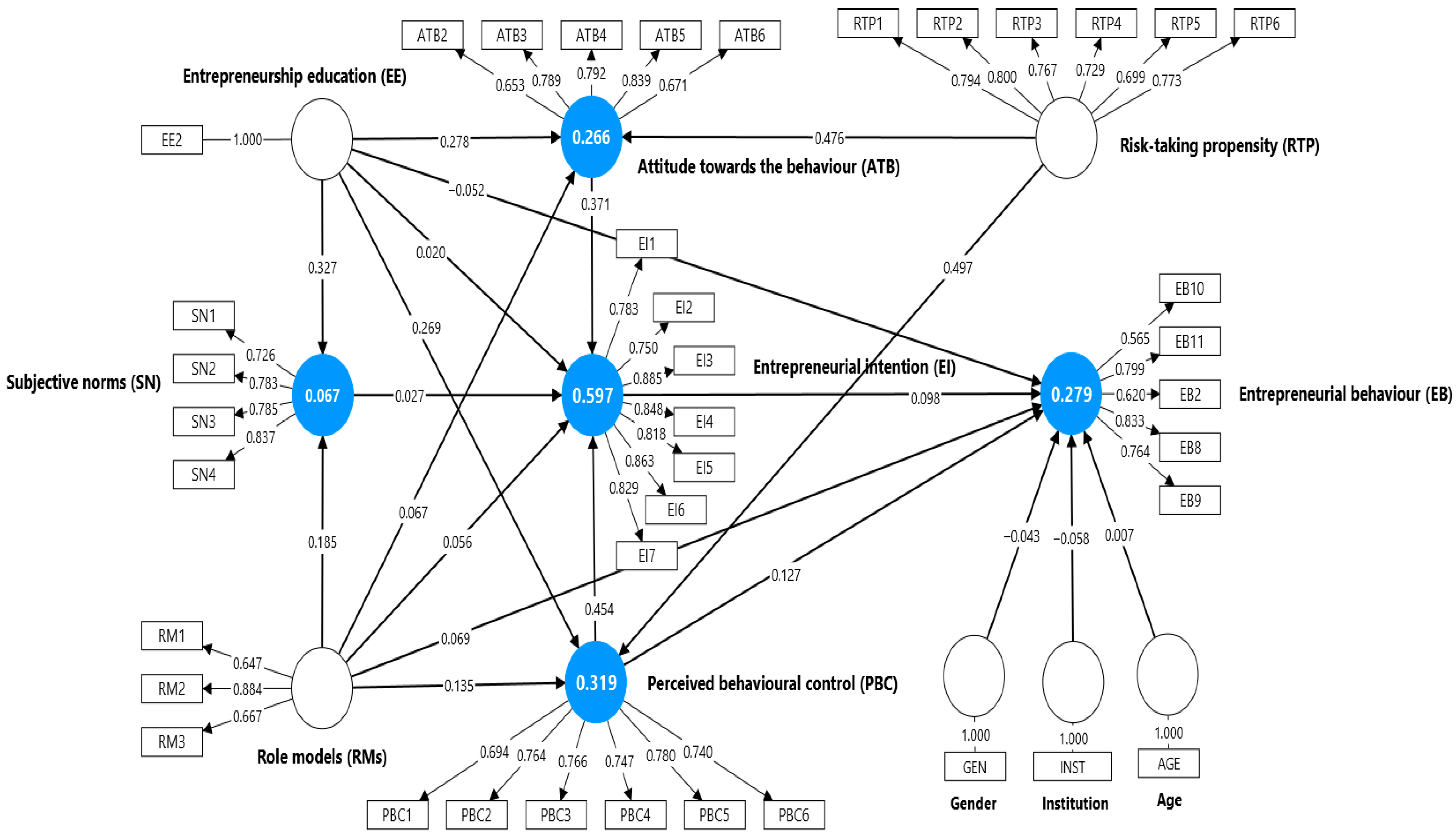

The coefficient of determination (R

2) was used to assess the model’s predictive power and to determine the extent to which the independent variables explain variance in the dependent variables. Demographic factors (age, gender, and institution) were included in the structural model as control variables and we tested their effects on EB. As depicted in

Figure 2, the exogenous constructs collectively explain 59.7% of the variance in Entrepreneurial Intentions (EI) (R

2 = 0.597). Specifically, Entrepreneurship Education (EE), Role Models (RM), and Risk-Taking Propensity (RTP) together account for 26.6% of the variance in Attitude Toward Behaviour (ATB) (R

2 = 0.266) and 31.9% of the variance in Perceived Behavioural Control (PBC) (R

2 = 0.319). EE and RM alone explain 6.7% of the variance in Subjective Norms (SN) (R

2 = 0.067). Furthermore, EE, RM, PBC, and EI collectively explain 27.9% of the variance in Entrepreneurial Behaviour (EB) (R

2 = 0.279).

Furthermore, effect sizes (f

2) were calculated to assess the individual contribution of each exogenous variable to the R

2 value of its corresponding endogenous variable. Following

Sarstedt et al. (

2017) guidelines, effect sizes are interpreted as minor (f

2 = 0.02), moderate (f

2 = 0.15), and large (f

2 = 0.35). As presented in

Table 5, the results show that the exogenous latent variables exhibited varying levels of influence on the endogenous latent variable, with effects ranging from negligible to minor, moderate, and, in some instances, large.

The predictive capability of the structural model was evaluated using Q

2 values, which assess the model’s ability to accurately reproduce observed data through the PLS estimation. A Q

2 value above zero signifies that the model possesses predictive relevance, while a value below zero indicates a lack thereof (

J. Hair & Alamer, 2022). As shown in

Table 6, all Q

2 values for the endogenous constructs are above zero, ranging from 0.046 to 0.309. This confirms that the model exhibits satisfactory predictive relevance across all constructs.

4.3. Analysis of Structural Paths for Hypothesis Testing

Results from the structural model (

Table 7) show that EE has a significant positive effect on ATB (β = 0.278,

p < 0.001), PBC (β = 0.269,

p < 0.001), and SN (β = 0.327,

p < 0.001). These findings suggest that exposure to EE fosters more positive attitudes toward entrepreneurship, strengthens individuals’ confidence in their ability to undertake entrepreneurial tasks, and increases perceived societal expectations to pursue entrepreneurial careers. However, EE does not exert a significant direct effect on EI (β = 0.020,

p = 0.370) or EB (β = −0.053,

p = 0.100), indicating that its influence operates indirectly through its impact on ATB, PBC, and SN. Accordingly, H4, H5, and H6 are supported, while H7 and H8 are not.

In relation to RM, the structural model results reveal that RM has a significant positive effect on EB (β = 0.070, p < 0.001), PBC (β = 0.135, p = 0.001), and SN (β = 0.185, p < 0.001). These findings suggest that the presence of RMs enhances individuals perceived capability to engage in entrepreneurial tasks and increases the perceived social pressure to pursue entrepreneurship, thereby promoting actual EB. However, RM does not have a significant effect on ATB (β = 0.067, p = 0.055) or EI (β = 0.056, p = 0.053), suggesting that the influence of role models is primarily mediated through PBC and SN rather than direct changes in attitudes or intentions. Accordingly, H10, H11, and H13 are supported, whereas H9 and H12 are not supported.

Findings related to RTP show significant positive effects on both ATB (β = 0.476, p < 0.001) and PBC (β = 0.497, p < 0.001). These findings indicate that individuals with a higher tendency to take risks are more likely to view entrepreneurial activity favourably and feel more capable of successfully performing entrepreneurial tasks. This underscores RTP as a critical personality trait that strengthens key antecedents of entrepreneurial intention. Therefore, H14 and H15 are supported.

Concerning the antecedents of intention, both ATB (β = 0.371, p < 0.001) and PBC (β = 0.454, p < 0.001) have strong, significant effects on EI. These results suggest that individuals who hold favourable attitudes toward entrepreneurship and perceive themselves as capable of executing entrepreneurial tasks are more likely to form strong EIs. In contrast, SN did not significantly influence EI (β = 0.027, p = 0.224), indicating that perceived social pressure does not play a substantial role in intention formation in this context. Accordingly, H1 and H2 are supported, whereas H3 is not supported.

Lastly, both EI (β = 0.096, p < 0.001) and PBC (β = 0.130, p < 0.001) significantly and positively influence EB. Additionally, PBC exerts a strong positive effect on EI (β = 0.454, p < 0.001), reinforcing its dual role in shaping both intention and behaviour. These findings suggest that individuals who feel confident in their entrepreneurial capabilities are more likely to form intentions to start a business and to act on those intentions. Moreover, the results highlight the mediating role of EI in translating antecedents into actual entrepreneurial behaviour. Therefore, H16 and H17 are supported.

In addition to the hypothesised relationships, demographic factors (age, gender, and institution) were included in the structural model as control variables to account for potential confounding effects on entrepreneurial behaviour. The results indicate that age (β = 0.007, p = 0.363) and gender (β = −0.042, p = 0.246) did not have a significant influence on entrepreneurial behaviour. Institution (β = −0.058, p = 0.069) also showed no significant effect, although the relationship was marginal. These findings suggest that entrepreneurial behaviour in this study was not explained by demographic characteristics but rather by the theoretical constructs under investigation.

5. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of EE and role RMs on EI, its antecedents, and subsequent EB among university and TVET college students. In addition, the study investigated the effect of RTP on ATB and PBC, as well as the direct influence of both EI and PBC on EB.

The findings showed that EE had a positive and significant effect on ATB, PBC, and SN; however, its direct effect on both EI and EB was found to be insignificant. These results align with those of

Duong (

2022) and

Silesky-Gonzalez et al. (

2025) who found that EE had a positive and statistically significant effect on ATB, PBC, and SN, but not on EI. However, the findings partially contradict those of

Tsaknis et al. (

2024) who reported that EE had a statistically significant effect on EI and PBC, but not on ATB or SN. These findings suggest that exposure to EE can enhance students’ confidence in their ability to perform entrepreneurial tasks, foster positive attitudes toward pursuing an entrepreneurial career, and increase their perception of social support or pressure to engage in entrepreneurial activity. The lack of a direct effect of EE on both EI and EB suggests that EE plays a preparatory role by shaping key psychological factors (ATB, PBC, and SN), which, in line with the TPB, mediate the relationship between external influences such as EE and the formation of intention. This highlights that the role of EE is more indirect than direct, extending previous findings by clarifying its function within the TPB framework.

The findings indicate that RMs have a positive and significant effect on PBC, SN, and EB, while their effect on ATB and EI was found to be insignificant. These findings support previous studies showing that RMs have a significant effect on PBC and SN, but not on ATB (

Aloulou, 2016) or EI (

Moreno-Gómez et al., 2020;

Saoula et al., 2025). These findings suggest that exposure to RMs can increase individuals’ confidence and perceived capability to start a business, enhance their perceived sense of prevailing social support or approval for entrepreneurial activity, and motivate actual enactment of EB, possibly through inspiration, informal guidance, or access to networks. However, the findings of this study contradict previous research that reported a statistically significant effect of RMs on ATB, PBC, and SN (

Choukir et al., 2019;

Feder & Niţu-Antonie, 2017;

Fellnhofer & Mueller, 2018), as well as on EI (

Malebana, 2016;

Maziriri et al., 2019). The lack of a significant effect of RMs on both ATB and EI may be attributed to contextual factors, such as the perceived relevance and accessibility of role models, and highlights that the influence of RMs may operate primarily through behavioural and social pathways (PBC, SN, and EB) rather than directly shaping attitudes or intentions. This provides a deeper theoretical understanding of how RMs function within the TPB framework among the study population.

The findings of this study further revealed RTP has a positive and significant effect on both ATB and PBC. These results align with those of

Caputo et al. (

2025), who also found a statistically significant effect of RTP on ATB and PBC. However, they contradict studies reporting an insignificant effect of RTP on PBC (

Munir et al., 2019) and on ATB (

Farrukh et al., 2018). These findings suggest that individuals with a higher propensity to take risks tend to have more positive attitudes toward EB and feel greater control over their ability to perform such behaviour. In other words, RTP plays an important role in shaping both the mindset and perceived capability needed to engage in entrepreneurship.

Additionally, the results indicate that both ATB and PBC have a positive and significant effect on EI, whereas SN do not. These findings corroborate prior research that reported significant effects of ATB and PBC on EI, but found no significant effect of SN (

Krueger et al., 2000;

Mothibi et al., 2024). These results suggest that an individual’s ATB and their perceived ability to perform entrepreneurial activities are more critical drivers of EI than external social expectations. In contrast, studies such as that by

Amrouni and Azouaou (

2024) reported that SN had a significant positive effect on EI, while ATB and PBC were not significant predictors.

Regarding the effect of both EI and PBC on EB, the study found that both variables have a significant positive influence on EB. Demographic variables had no effect on EB. These findings corroborate those of previous studies that reported a significant effect of both EI and PBC on EB (

Kautonen et al., 2015;

Mothibi et al., 2025;

Nergui, 2020;

Shiri et al., 2017;

Valencia-Arias & Restrepo, 2020). However, the results contradict the findings of other studies, which reported that EB is significantly influenced by EI only, with no significant effect from PBC (

Iskandar & Said, 2021;

Joensuu-Salo et al., 2020;

Linan & Rodríguez-Cohard, 2015). The significant positive effects of both EI and PBC on EB suggest that EI alone may be insufficient to drive entrepreneurial action, particularly among student populations who often face structural and resource-related constraints. In such contexts, PBC plays a crucial role by reflecting students’ confidence in their ability to overcome obstacles and engage in entrepreneurial activities.