Abstract

This exploratory study aims to identify the state of well-being of a select group of women leaders in a Mexican university by analyzing the relationship between their perception of happiness and their satisfaction with their life and work. Through the application of a psychometric battery, this work examined how these leaders manage their well-being within an environment that is simultaneously empowering and demanding. Methodologically, a descriptive statistical analysis was performed, including a correlation analysis of all items. As a result, the research identified positive correlations between the variables age and positive perceptions of work and life, which are strongly associated with high personal and professional satisfaction. In addition, people who find their work rewarding and feel that their life is close to their ideal tend to be more satisfied in general. Although this study intended to be exploratory, it also sought to contribute a deeper understanding of the well-being status of women in university leadership positions in Mexico. In doing so, it filled an important gap in the literature on gender, leadership, and well-being in Latin American academia by highlighting the complexity of managing and supporting women in leadership positions.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, interest in the health and well-being of academicians in higher education institutions has grown significantly. Most studies have focused on the well-being of students, leaving a notable lack of attention to the well-being of employees, especially those in leadership positions (Cuesta-Valiño 2021). This lack is even more pronounced regarding women in leadership roles. Their unique experiences and specific challenges are often not adequately addressed in research. The university, as a social microcosm, reflects the power dynamics and gender roles in society. In Mexico, where patriarchal structures and traditional cultural norms still predominate in many sectors, women leaders face specific barriers that can affect their physical, emotional, and professional well-being (Campos-García 2020).

This study focuses on the well-being status of a select group of women leaders at a Mexican university, acknowledging the unique challenges and opportunities they face in a particularly diverse cultural and educational context. Through the application of a psychometric battery, this work examined how these leaders manage their well-being in an environment that is simultaneously empowering and demanding, considering their states of happiness, life satisfaction, and job satisfaction. Methodologically, this study employed descriptive statistical analysis, including a correlation analysis of all variables. Although this study intended to be exploratory, it also sought to contribute a deeper understanding of the well-being status of women in university leadership positions in Mexico.

This text is structured by beginning with an exhaustive review of previous literature related to life satisfaction, job satisfaction, and how these aspects are related to happiness and overall well-being. It then details the methodology used in this study, including the hypothesized relationships, the variables considered, the instruments used, and the process of implementation and data analysis. After establishing this framework, the results are presented and analyzed using the theoretical framework to identify and discuss the main findings. Finally, the text concludes by presenting the limitations of this study and suggesting possible future research lines that could expand and deepen these findings.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Life Satisfaction

Life satisfaction refers to people’s overall assessment of their existence as positive or satisfying (Nani et al. 2024). This concept encompasses multiple dimensions, such as emotional well-being, mental and physical health, and perceptions of personal fulfillment and achievement. For workers, and especially for leaders in institutions, life satisfaction is critical, as it directly influences their ability to manage stress, make effective decisions, and foster a positive environment (Alonderiene and Majauskaite 2016). In academic environments such as universities, where challenges are continuous and expectations high, maintaining a high level of life satisfaction can be crucial for leadership sustainability and institutional success (Rubino et al. 2022). Moreover, university leaders often face the duality of administrative and academic pressures; life satisfaction is a buffer against professional burnout. A fulfilling personal life allows leaders to maintain energy, keep a balanced perspective, and improve their interactions with colleagues and students (Asma 2023). This not only enhances their individual quality of life but also facilitates more effective management, thus boosting productivity and the organizational climate of the entire university (Samad et al. 2022).

For women in university leadership positions, life satisfaction takes on additional dimensions and particular challenges. Historically, women have faced structural barriers and gender biases that can affect both their personal well-being and life satisfaction (Merma-Molina et al. 2022). Therefore, achieving a high degree of life satisfaction is crucial for female leaders to remain resilient and effective (Rohit et al. 2023). An enriching and fulfilling personal life provides them with the emotional and psychological tools necessary to face and overcome professional challenges, thus promoting balanced and empathetic leadership (Caroline et al. 2022).

2.2. Job Satisfaction

In terms of job satisfaction, this concept encompasses individuals’ perceptions of their work environment, the tasks they perform, and the relationships they cultivate in the professional environment (Mahadev et al. 2023). Job satisfaction is particularly critical for leaders in educational institutions, as high job satisfaction not only improves individual performance but also translates into more effective leadership and the promotion of a healthy and productive academic environment (Mugira 2022). Leaders who are satisfied with their work tend to be more innovative, more committed to the mission of the institution, and better able to motivate and retain academic talent.

Specifically, in the context of universities, where success depends mainly on the synergy between administration, faculty, and students, leaders’ job satisfaction becomes an essential element that directly impacts the morale and efficiency of the entire university community (Cerci and Dumludag 2019). Leaders who experience high role satisfaction are better able to manage the pressures inherent in their positions and foster a work environment that prioritizes the well-being and professional development of all its members, thus ensuring continuous progress and innovation within the institution (Horoub and Zargar 2022).

Job satisfaction is fundamental to fostering a culture of equality and diversity within institutions. Satisfied women leaders not only demonstrate more commitment and productivity but also act as role models for other women in the academic community, fostering a more inclusive climate (Padmanabhanunni et al. 2023). Job satisfaction enables them to implement policies and practices that proactively address gender disparities and promote a fairer and more motivating work environment for all, which is essential for continued institutional advancement and innovation (Beddow 2018).

2.3. The State of Happiness as a Fundamental Part of Well-Being

Happiness, understood as an experience of satisfaction and fulfillment, is vital to people’s overall well-being. From a psychological perspective, happiness correlates with positive emotions and a sense of purpose in life, which are elements that contribute to mental and physical health (Schnurr 2008). In this context, well-being is a multidimensional condition that includes emotional stability, personal satisfaction, and optimal health, all of which are reinforced by happiness (Cuesta-Valiño 2021).

The relationship between happiness and well-being manifests significantly in the workplace. Happy workers tend to be more productive, show higher levels of commitment to their work, and have stronger interpersonal relationships with their colleagues (Cruz-Tarrillo 2023). Happiness at work translates into lower rates of absenteeism and turnover and fosters a more creative and cooperative work environment. These characteristics are particularly valuable in high-demand contexts such as educational institutions (Wang and Milyavskaya 2020).

Happiness amplifies life satisfaction. Individuals reporting high levels of happiness generally evaluate their lives more positively, which reinforces their overall well-being. This positive feedback loop of joy and life satisfaction is critical for maintaining good mental health and promoting a balanced and fulfilling lifestyle (Setiyowati and Irtaji 2017).

Happiness also profoundly influences job satisfaction. In environments where individuals feel joy and contentment with their daily tasks, there is greater alignment with organizational goals and more enthusiasm for collective success (Bautista et al. 2023). This becomes especially relevant in leadership roles, where the ability to convey positivity inspires and motivates entire teams, improving everyone’s overall performance and job satisfaction (Raime et al. 2022).

Regarding women leaders, the gender perspective adds complexity to the relationship between happiness and well-being. Women in leadership positions often face unique challenges, including differentiated performance expectations and the need to negotiate their roles in traditionally male-dominated structures (Demircioglu 2014). For them, happiness is not only an essential component of their personal and professional well-being but also a powerful tool for overcoming obstacles and biases in the workplace (Strukova and Polivanova 2023). When these leaders experience high levels of personal and job satisfaction, they are better equipped to implement policies that benefit all employees, thus attaining a fairer and more motivating environment (Campos-García 2020).

Furthermore, happy women in leadership roles can redefine cultural norms and expectations in their institutions (Salas-Vallina 2018). By demonstrating that it is possible to balance personal life with challenging professional demands, these women not only improve their well-being but also become role models for other aspiring leaders, expanding opportunities and improving the work climate for future generations of women (Milhouse 2006). In this sense, happiness is an indispensable element of overall well-being, and its impact is even more significant for women leaders in academia. By fostering happiness and satisfaction in all aspects of life, these leaders enrich their experiences and contribute to the well-being and progress of their communities and organizations (Burkinshaw and White 2017).

3. Methodology

This exploratory and quantitative study aimed to analyze the correlation between happiness among a group of female managers at a higher education institution in Mexico and their states of personal and occupational satisfaction. The research design intended to measure the participants’ perceptions of their states of happiness, individual and job satisfaction objectively. For this measurement, a psychometric battery combined three standardized instruments to quantify these variables, thus facilitating comparisons and rigorous analyses of the data.

The hypothesis of this study is the following:

H1:

Personal and occupational satisfaction is positively correlated with levels of subjective happiness in female managers in a higher education institution in Mexico, suggesting that higher levels of satisfaction in these variables are associated with higher levels of happiness.

In this sense, the following variables are proposed:

- Independent variables: life satisfaction and job satisfaction.

- Dependent variable: level of subjective happiness

This hypothesis is based on the theory that happiness is multifaceted and can be significantly influenced by well-being in different areas of life, especially in personal and professional environments.

3.1. Context and Sample

This research occurred in a private higher education institution in Mexico. The university has campuses throughout Mexico, so the sample included women from different parts of the country. The study participants were 204 women, with an average age of 43 years, who held managerial positions in the institution and voluntarily participated in the research. The sample was selected with a confidence level of 90% and a margin of error of 10% from the approximate total population of 2430 female managers in positions with the characteristics, including administrative and academic leaders. Notably, the quantitative data collection adhered to the ethical parameters set by the institution, respecting the terms and conditions for organizational research, including the care and confidentiality of the results, which can only be used for academic purposes.

3.2. Data Collection Instruments

This study utilized three validated and standardized instruments:

- Sonja Lyubomirsky’s General Happiness Scale: This scale, developed by Sonja Lyubomirsky, is known as the “Subjective Happiness Scale” (SHS). This self-assessment tool measures a person’s overall level of happiness using a scale that includes questions that assess the extent to which people consider themselves to be happy or unhappy relative to peers (comparison). This scale can be helpful in understanding managers’ perceptions of their happiness in personal and comparative contexts.

- Diener, Emmons, Larsen, and Griffin’s “Satisfaction with Life Scale” (SWLS) measures a person’s overall satisfaction with life. It comprises a series of statements that participants rate according to their agreement or disagreement, providing an overall measure of life satisfaction. This scale is particularly relevant for assessing how women managers feel about their lives in general, beyond the work environment.

- Wrzesniewski, McCauley, Rozin, and Schwartz’s “Work-Life Survey” assesses how people perceive their work activity in three categories: job, career, and vocation. The survey seeks to understand the meaning and satisfaction people find in their work, which is crucial for assessing their well-being at work. The survey helps understand how university managers’ work influences their overall well-being and how this aspect integrates into their total life.

These three scales can be interrelated to provide a holistic view of the well-being of women in a sample. While the Lyubomirsky and Diener scales give a general overview of personal well-being and life satisfaction, the Wrzesniewski survey specifically assesses the work dimension, which indeed connects to the concept of general well-being. Combining these tools makes it possible to obtain a complete picture that integrates personal and professional aspects of well-being.

3.3. Implementation and Data Analysis

In order to obtain the data, contact was made with different areas of the educational institution, as well as with leaders who were in charge of women leaders who could participate in this study. The application was carried out by means of digitalizing the instruments into a single Microsoft form, ensuring that each participant expressed their desire to participate and was aware that their responses would be used for research purposes. The implementation was carried out in Spanish.

It is important to note that this implementation is supported by the interdisciplinary research group R4C of the Institute for the Future of Education of the Tecnológico de Monterrey, with the approval of the institutional ethics committee ID: IFE-2024-01, which assessed the implementation as low risk. The entire study was carried out in accordance with the terms and conditions of the Research for Challenges Privacy Notice (https://tec.mx/es/aviso-privacidad-research-challenges (accessed on 18 March 2024)).

Methodologically, this study employed a descriptive statistical analysis, including a correlation analysis.

4. Results

For the sake of clarity, this paper first presents the results by instrument and then aggregates them with the correlation of all items.

4.1. State of General Happiness (SHS)

This instrument’s results show that the participants generally perceive themselves as quite happy. The mean of 3.56 on a scale of 1 to 5 indicates that the majority consider their level of happiness to be high; the moderate standard deviation (0.580) suggests low variability in their perceptions. Furthermore, when compared to the majority of people around them, respondents considered themselves slightly happier, with a mean of 3.01 and a more significant dispersion (0.866), suggesting a variable perception of relative happiness.

In terms of resilient happiness, participants tended to see themselves as people who enjoy life and maintain a positive attitude despite circumstances, with a mean of 3.87 (high) and a low dispersion (0.516). On the other hand, although some see themselves as less happy than they would like, the mean of 2.10 suggests that, in general, they do not see themselves as unhappy. However, there is moderate variability (0.723) in these perceptions. Overall, the results reflect positive self-perceptions of happiness among the respondents (Table 1).

Table 1.

General happiness status.

Regarding the question “In general, I consider myself…” (see Figure 1), the majority of female managers considered themselves to be moderately happy, with a significant portion describing themselves as very happy, indicating a high degree of personal satisfaction. Few identified themselves as unhappy, reflecting a low level of overall dissatisfaction. There were no neutral responses, suggesting that respondents had a clear perception of their happiness. Overall, the responses indicated a level of optimism or satisfaction with life among the female managers in the study.

Figure 1.

In general, I consider myself to be.

In the second item, the majority indicated feeling happier than the people around them, suggesting a high degree of personal satisfaction (see Figure 2). A good proportion also considered themselves to be moderately happier, supporting the idea that these women generally felt happier compared to others. A small segment saw themselves as equally happy as their peers, and a few considered themselves moderately less happy, with none in the less happy category. This distribution reflects a sense of confidence or accomplishment associated with their leadership positions and professional success (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Compared to most people around me, I consider myself.

Regarding the third item (see Figure 3), which focused on the ability to maintain a state of happiness despite circumstances, the majority responded “Many times”, indicating that they tend to be very happy and enjoy life despite challenges. A significant proportion responded “Always”, suggesting a high capacity for resilience and a consistently positive approach. A small segment responded, “Sometimes”, indicating that while they are generally happy, some circumstances affect their moods. Very few selected “Few times”, and none chose “Never.” This pattern suggests a high level of psychological well-being and a tendency toward optimism among women in leadership roles, which is helpful in facing challenges.

Figure 3.

Some people tend to be very happy. They enjoy life regardless of what happens, coping with most circumstances. To what extent do you consider yourself such a person?

The fourth item (see Figure 4) addresses the frequency with which participants consider themselves less happy than they would like to be, without being depressed. Most responded, “Few times”, suggesting that they do not usually feel unhappy without apparent cause. This indicates that, although they are not always extremely happy, they do not experience a noticeable lack of happiness in their daily lives. A significant portion responded, “Sometimes”, indicating that they occasionally feel that they are not as happy as they would like to be, but not consistently. A small fraction responded, “Many times”, and none chose “Always”, indicating that few chronically felt less happy than desired. A relevant segment responded, “Never”, showing that some female managers never feel unhappy without an apparent reason. These results reflect a balance in the perceived happiness and well-being among women managers, indicating that most did not feel persistently unhappy or dissatisfied, despite the challenges of their roles.

Figure 4.

Some people tend to be very unhappy. Although they are not depressed, they do not seem as happy as they would like to be. To what extent do you consider yourself such a person?

4.2. Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS)

Initially, the survey participants reported high levels of satisfaction and closeness to their real lives (Table 2). The majority felt that their lives were close to their ideal (mean 8.12 out of 10), with a variability of 1.051. In addition, they considered their life conditions to be excellent (8.25/10) and expressed a high level of satisfaction with their life (8.58/10). In general, the majority were happy in life to the point that, if they were born again, they would change almost nothing (7.96/10).

Table 2.

Satisfaction with Life.

However, to have a better view of the results of these questions, we used meter or indicator graphs, specifically the Net Promoter Score (NPS). Although these graphs are more common in the business world, we believe that they are more explanatory than a bar chart. It is important to note that the sum of the percentages shows a difference of 3–4%, which corresponds to several responses that are not significant.

In the first question (Figure 5), the responses were grouped into promoters (35%), passives (53%), and detractors (8%). An NPS of 28 suggests that the majority perceived their life to be close to ideal, reflecting significant satisfaction. However, the predominance of passives indicates that, although the majority were satisfied, they did not feel fully realized. This highlights the potential for improving the personal and professional fulfillment of these female managers to close the gap between their current situation and their ideal life.

Figure 5.

Generally speaking, my life is close to my ideal.

In the second question (Figure 6), the results show that 44% of female managers were promoters, considering their living conditions to be excellent, reflecting a high degree of satisfaction. Passives, who constituted 43%, were satisfied, but they were not satisfied enough to promote this perception actively. Detractors, 9%, indicated specific areas of dissatisfaction. An NPS of 37, generally considered good, suggests that the majority were quite happy with their living conditions. However, the significant presence of passives indicates that, although many were satisfied, they did not feel that their living conditions met the highest standard of excellence uniformly. This positive perception of living conditions contributes to professional and personal performance, providing a stable and satisfying environment that facilitates effective leadership and individual well-being.

Figure 6.

In general terms, my living conditions are excellent.

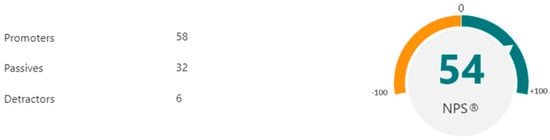

In the third item (Figure 7), the overall life satisfaction of the participants was evaluated, with the following results: 58% were promoters, indicating a high degree of satisfaction; 32% were passive, being moderately satisfied but without reaching the level of promoters; and 6% were detractors, reflecting only a few with significant dissatisfaction. An NPS of 54 is evidence of a high level of overall satisfaction among women managers, suggesting that most found their lives are rewarding and satisfying. This result is an excellent indicator of personal well-being, and the low percentage of detractors reinforces the idea of minimal dissatisfaction. A high level of personal satisfaction can also positively impact their performance in leadership roles, as satisfaction with personal life tends to improve work effectiveness and motivation.

Figure 7.

In general terms, I am satisfied with my life.

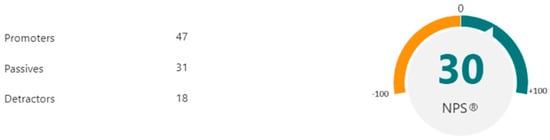

In the fourth item (Figure 8), the participants’ perception of the statement “If I were born again, I would change almost nothing in my life” was evaluated, with the following results: 47% were promoters, indicating a high degree of satisfaction and acceptance with their current life; 31% were passive, showing satisfaction, but with some reservations about possible changes; and 18% were detractors, expressing a significant desire to change substantial aspects of their life if they had the opportunity. An NPS of 30 indicates that a notable majority of women managers felt that they had lived a satisfying life and made good decisions overall. This satisfaction reflects personal well-being and can influence how they approach future challenges and opportunities, providing a sense of security and confidence in their choices and lived experiences. Although there is room for improvement in how some retrospectively perceived their lives, most felt positive and content with their experiences and decisions.

Figure 8.

If I were born again, I would change almost nothing about my life.

4.3. Working Life Perception Survey

The survey results reveal a high overall satisfaction among respondents with their work. Most respondents found their work rewarding, with a mean of 4.41 on a scale of 1 to 5, and believed that it contributes positively to the world (4.39). In addition, they enjoyed talking about their work with others (4.45). Many had aspirations to advance their careers, expecting to be in a higher level position in five years (4.13), and would choose their current working life again (4.27). However, there was notable variability in looking forward to retirement (mean 2.87) and anticipation of weekends (mean 3.51), indicating some level of job burnout.

On the other hand, while some respondents took work home (mean 2.92) and thought about work outside of working hours (mean 2.83), many did not expect to be in the same job in five years (mean 2.32), reflecting a desire for career change or advancement. Financial motivation plays a moderate role in their work, with a mean of 2.92, and while work is important to many (3.66), not all saw it as an absolute life necessity (2.68). Combined, these results suggest considerable job satisfaction but also indicate areas of attrition and aspirations for change in the future (Table 3).

Table 3.

Perception of working life.

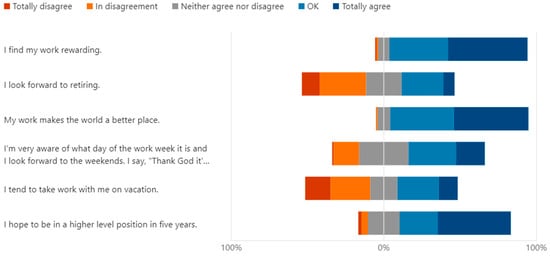

We separated the specific responses into blocks of six items for better analysis. The results of the first group of items (Figure 9) suggest that women managers showed a high level of satisfaction and positive valuation of their work, characterized by perceived gratification and belief in the positive impact of their job roles on the world. There was a clear ambition to move up the career ladder in the next five years, reflecting an optimistic view of career development. Although some expressed a desire to retire, a significant proportion still found satisfaction in their current jobs and did not anxiously anticipate retirement. Most valued work–life balance, showing a tendency not to take work with them on holidays, although there was a minority who did, possibly due to intense work demands or high levels of professional commitment. These findings suggest a healthy mix of job satisfaction, job purpose, and growth expectations, indicating a balanced execution of managerial responsibilities and personal well-being.

Figure 9.

Perception of working life—items 1–6.

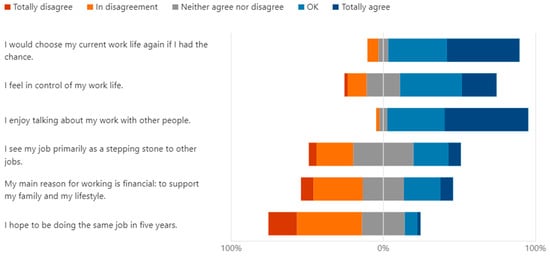

The results of questions 7–12 (Figure 10) show that the majority of women managers were delighted with their current careers and would choose their current working life again if they could. They felt in control of their work roles and enjoyed sharing their work with others, indicating a high level of commitment and pride in what they do. While some saw their job as a stepping stone, many valued their current positions as stable and rewarding in the long term. Financial motivation was not uniformly dominant, with some also seeking personal fulfillment, challenge, or social contribution. Most expected to continue doing the same work for the next five years, reflecting satisfaction and positive perspectives of their continued development and contribution in their current roles. These findings underline the diversity of motivations and expectations among female managers, providing a detailed picture of how they perceive their working lives and future aspirations.

Figure 10.

Perception of working life—items 7–12.

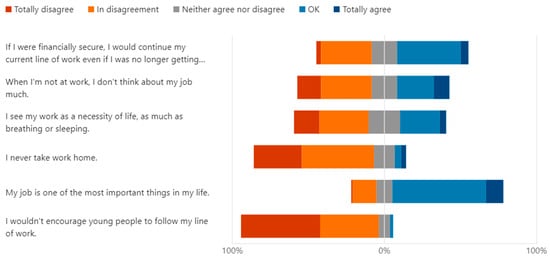

Items 13–18 (Figure 11) revealed that women managers showed strong commitment and deep identification with their work. Many would continue in their current careers even without additional remuneration, highlighting a significant emotional commitment beyond financial security. The ability to disconnect from work outside working hours varied considerably, reflecting different approaches to stress management and work–life balance. Some saw their work as essential to their existence, while others did not. Most recognized that work extends beyond official hours, typically in high-responsibility roles. In addition, many perceived their work as one of the most essential things in their lives. They would encourage young people to pursue a similar career, which underlines their satisfaction and the meaning they found in their professional roles. These responses provide a rich insight into how these women value their work and its impact, both personally and for future generations.

Figure 11.

Perception of working life—items 13–18.

4.4. Relationship between the Level of Happiness and the Perception of Personal and Job Well-Being

The results of the Pearson correlation table (Appendix A) present several significant correlations between different variables related to perceived happiness and job satisfaction. First, age shows significant positive correlations with several key aspects of personal satisfaction and perception among the participants. Notably, as age increases, so do positive perceptions of how close life is to the desired ideal (r = 0.264, p < 0.05), the consideration of living conditions as excellent (r = 0.318, p < 0.01), general satisfaction with life (r = 0.204, p < 0.05), degree of job gratification (r = 0.264, p < 0.05), enjoyment in talking about their work with others (r = 0.252, p < 0.05), and willingness to continue working even without pay if they were financially secure (r = 0.272, p < 0.01).

Second, the strong positive correlation between overall self-rated happiness (item 2) and favorable comparison with others (item 3) stands out, indicating that those who considered themselves very happy tended to perceive their lives more positively compared to their peers (r = 0.421, p < 0.01). In addition, those who reported high levels of happiness (item 4) also showed positive correlations with overall self-rated happiness (r = 0.389, p < 0.01) and favorable comparison with others (r = 0.295, p < 0.01). In contrast, the perception of being less happy than desired (item 5) correlates negatively with several measures of personal satisfaction and perceived happiness.

Third, it is evident that people who consider their life to be close to their ideal (item 6) show significant positive correlations with overall life satisfaction (r = 0.787, p < 0.01) and perception of excellent living conditions (r = 0.679, p < 0.01). Likewise, finding work rewarding (item 10) is positively associated with general life satisfaction (r = 0.457, p < 0.01) and considering life close to the ideal (r = 0.486, p < 0.01).

Finally, regarding the work and personal domain, those who tended to take work on holidays (item 14) showed negative correlations with life satisfaction (r = −0.323, p < 0.01) and considering life close to the ideal (r = −0.291, p < 0.01). On the other hand, those who would choose their current working life if they had the opportunity (item 16) showed positive correlations with the consideration of life close to the ideal (r = 0.385, p < 0.01) and life satisfaction (r = 0.459, p < 0.01).

5. Discussion

The hypothesis proposed in this study, which postulates a positive correlation between personal and job satisfaction and levels of subjective happiness among women leaders in a higher education institution in Mexico, is confirmed by the following findings:

- The data reflect high satisfaction in both personal and professional life among female leaders, indicating good emotional balance and overall well-being. The literature suggests that personal well-being can positively impact job performance and satisfaction (Judge et al. 2001). This phenomenon is also supported by resource and job demands theory, which suggests that resources such as a sense of achievement and control over work can buffer the impact of high job demands, mitigating burnout and promoting engagement (Bakker and Demerouti 2007). These aspects, which reflect high levels of satisfaction, are directly related to greater subjective happiness, confirming the study hypothesis.

- Despite the reported high satisfaction, concerns related to work–life balance were also observed, such as difficulty in disconnecting from work and the tendency to bring work home, which are factors known to lead to burnout and negatively affect mental health (Sonnentag 2012). The effective management of work–life balance is crucial and supported by research emphasizing the importance of flexible organizational policies (Kossek et al. 2011), suggesting that improvements in this area could further raise the levels of subjective happiness.

- Women leaders showed strong identification with their work roles, seeing their work as essential to their lives. While this strong identification can be a source of motivation and satisfaction, it also carries risks during periods of job change or uncertainty (Ashforth 2001). The caution expressed about recommending their careers to young people suggests an awareness of the challenges inherent in their roles, which may also influence their general well-being and subjective happiness.

- The diverse motivations for working, from financial reasons to the pursuit of personal fulfilment, reflect a plurality of drivers behind these women’s careers. This highlights the need for a human resource management approach that recognizes and cultivates these different motivations to maximize satisfaction and performance (Kristof-Brown et al. 2005). The alignment between personal motivations and job characteristics can significantly improve job satisfaction and thus the levels of subjective happiness.

In terms of correlations between all variables, age and positive perceptions of work and life strongly correlate with higher personal and career satisfaction. People who find their work rewarding and feel that their life is close to their ideal tend to be more satisfied in general. The negative correlations between performing work on holidays and life satisfaction suggest that a better separation between work and personal life may contribute to greater happiness. In addition, financial motivations moderately impact perceptions of work, indicating that personal satisfaction and control over working life are crucial factors in the respondents’ overall happiness.

All these findings strongly support the initial hypothesis, showing a clear correlation between personal and occupational satisfaction and subjective happiness. These results suggest that interventions aimed at improving satisfaction in these domains could have a direct and positive impact on the happiness of managers in higher education.

6. Conclusions

This study contributes theoretically and practically to spotlighting job satisfaction and personal well-being among women in leadership positions. The theoretical implications of this study are that high personal and professional satisfaction among women leaders supports the theory of job resources and demands, highlighting that emotional balance and personal well-being can increase job performance. Furthermore, the strong identification of these women with their work coincides with work identity theory, suggesting that the fusion of self-concept with career success can be both motivating and risky in periods of job uncertainty. The diverse work motivations observed also reflect the person–job fit theory, highlighting the importance of aligning individual motivations with job characteristics to enhance job satisfaction and performance.

The practical implications of this study highlight two critical areas for organizational development. First, the implementation of flexible policies that balance the work and personal lives of women leaders is crucial to mitigate burnout and promote mental health. It involves adapting organizational strategies to manage work and personal responsibilities effectively. Second, organizations must provide strong support for women in leadership roles by fostering support networks that recognize and promote diverse work motivations. This approach can not only increase job satisfaction but also enhance performance in their leadership roles.

6.1. Methodological Limitations

This exploratory and initial study does not claim to achieve a comprehensive understanding of the subjective well-being of women in leadership positions. Instead, it seeks to establish a foundation on which future studies can be built. Furthermore, this study focuses specifically on the context of a private university in Mexico, considering the particularities that this environment can imprint on the experience of well-being. By focusing on women in leadership positions, the research provides valuable findings on how gender and power dynamics influence well-being in the workplace.

The results, although limited by the scope of the quantitative methodology, are significant and relevant, as they provide a starting point for deeper discussions and developing future research that could adopt mixed or qualitative approaches further to explore the narrative and personal experiences of women managers. The findings of this study provide valuable information for policymakers and the university authorities interested in improving the well-being of their staff. They highlight the importance of fostering emotional well-being to enhance work efficacy and satisfaction and emphasize the need for flexible policies that promote a better work–life balance. Additionally, they underscore the gender dynamics and “double burden” faced by women in leadership positions. Moreover, these results allow for the recognition and development of various work motivations, which can maximize both satisfaction and performance. These insights offer a solid foundation for future research and the development of evidence-based policies aimed at creating healthier and more equitable work environments.

6.2. Future Research

To advance understanding of the dynamics and needs of women leaders, we propose several lines of future research. First, longitudinal studies should examine how the perceptions and satisfaction of these women evolve over time and in response to various organizational interventions. In addition, extending the sample to different sectors and regions would improve the generalization of results and reveal cultural variations in job satisfaction and well-being. It would be equally beneficial to investigate the effectiveness of specific policies and organizational practices designed to improve work–life balance and overall satisfaction among women in leadership positions. Complementing these quantitative approaches with qualitative studies would provide a deeper understanding of the experiences and perceptions of these leaders in specific work contexts. In sum, these lines of research would not only strengthen support for women leaders but also improve organizational effectiveness as a whole by promoting a more equitable and satisfying work environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.O.-M. and J.C.V.-P.; methodology, E.M.G.-L.; software validation, E.M.G.-L.; formal analysis, E.M.G.-L.; investigation, V.O.-M. and J.C.V.-P.; resources, J.C.V.-P.; data curation, E.M.G.-L.; writing—original draft preparation, V.O.-M.; writing—review and editing, J.C.V.-P.; visualization, E.M.G.-L.; supervision, J.C.V.-P.; project administration, J.C.V.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The present study was validated by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Tecnologico de Monterrey, who assessed the research as low risk. ID. IFE-2024-01.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions and data presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial and technical support of Writing Lab, Institute for the Future of Education, Tecnologico de Monterrey, Mexico, in producing this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. All co-authors have seen and agree with the contents of the manuscript and there is no financial interest to report.

Appendix A. Pearson Correlation

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | In general, I consider myself | 0.199 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Compared to most of the people around me, I consider myself: | 0.085 | 0.421 ** | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | Some people tend to be very happy. They enjoy life no matter what happens, coping with most circumstances. How happy do you consider yourself to be? | 0.282 ** | 0.389 ** | 0.295 ** | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | Some people tend to be very unhappy. Although they are not depressed, they don’t seem as happy as they would like to be. How happy do you consider yourself to be? | −0.084 | −0.286 ** | −0.349 ** | −0.316 ** | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | Generally speaking, my life is close to my ideal. | 0.264 * | 0.639 ** | 0.345 ** | 0.389 ** | −0.330 ** | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | The conditions of my life are excellent. | 0.318 ** | 0.426 ** | 0.350 ** | 0.410 ** | −0.366 ** | 0.679 ** | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | I am satisfied with my life. | 0.204 * | 0.593 ** | 0.460 ** | 0.366 ** | −0.389 ** | 0.787 ** | 0.658 ** | |||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | If I were born again, I would change almost nothing about my life. | 0.090 | 0.335 ** | 0.187 | 0.096 | −0.192 | 0.493 ** | 0.374 ** | 0.494 ** | ||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | I find my work rewarding. | 0.264 * | 0.441 ** | 0.226 * | 0.304 ** | −0.212 * | 0.486 ** | 0.310 ** | 0.457 ** | 0.315 ** | |||||||||||||||||

| 11 | I am looking forward to retirement. | 0.020 | −0.101 | 0.011 | −0.047 | 0.041 | 0.034 | 0.036 | −0.092 | 0.123 | −0.100 | ||||||||||||||||

| 12 | My work makes the world a better place. | 0.056 | 0.322 ** | 0.465 ** | 0.233 * | −0.358 ** | 0.280 ** | 0.124 | 0.370 ** | 0.208 * | 0.235 * | −0.074 | |||||||||||||||

| 13 | I am very conscious of what day of the work week it is, and I look forward to the weekends. I say, “Thank God it’s Friday!” | −0.255 * | −0.151 | −0.055 | −0.183 | 0.124 | −0.197 | −0.063 | −0.290 ** | 0.020 | −0.213 * | 0.431 ** | 0.012 | ||||||||||||||

| 14 | I tend to take work with me on holidays. | −0.063 | −0.342 ** | −0.132 | −0.238 * | 0.042 | −0.291 ** | −0.226 * | −0.323 ** | −0.001 | −0.263 * | 0.156 | −0.099 | 0.276 ** | |||||||||||||

| 15 | I hope to be in a higher-level position in five years. | −0.045 | 0.024 | 0.149 | 0.201 | −0.152 | −0.138 | 0.051 | −0.033 | −0.013 | −0.027 | −0.061 | 0.037 | 0.063 | −0.116 | ||||||||||||

| 16 | I would choose my current work life again if I had the opportunity. | 0.077 | 0.339 ** | 0.294 ** | 0.362 ** | −0.346 ** | 0.385 ** | 0.237 * | 0.459 ** | 0.159 | 0.549 ** | −0.177 | 0.325 ** | −0.353 ** | −0.196 | −0.039 | |||||||||||

| 17 | I feel in control of my work life. | 0.175 | 0.444 ** | 0.293 ** | 0.352 ** | −0.365 ** | 0.480 ** | 0.366 ** | 0.397 ** | 0.194 | 0.546 ** | −0.131 | 0.284 ** | −0.161 | −0.222 * | −0.035 | 0.395 ** | ||||||||||

| 18 | I enjoy talking about my work with other people. | 0.252 * | 0.443 ** | 0.422 ** | 0.284 ** | −0.345 ** | 0.385 ** | 0.310 ** | 0.454 ** | 0.416 ** | 0.552 ** | −0.007 | 0.488 ** | −0.155 | −0.222 * | 0.071 | 0.433 ** | 0.473 ** | |||||||||

| 19 | I see my job mainly as a stepping stone to other jobs. | −0.093 | −0.087 | −0.051 | −0.019 | −0.017 | −0.085 | −0.019 | −0.139 | −0.138 | −0.035 | 0.182 | −0.214 * | 0.177 | −0.091 | 0.219 * | −0.103 | 0.088 | −0.102 | ||||||||

| 20 | My main reason for working is financial: to support my family and my lifestyle. | −0.109 | −0.237 * | 0.012 | −0.112 | 0.050 | −0.196 | −0.200 | −0.250 * | −0.343 ** | −0.195 | 0.118 | −0.201 | 0.185 | 0.077 | 0.223 * | −0.265 * | −0.142 | −0.262 * | 0.298 ** | |||||||

| 21 | I hope to be doing the same job in five years. | −0.083 | −0.035 | 0.127 | 0.041 | −0.108 | 0.091 | 0.085 | 0.039 | −0.037 | 0.267 ** | 0.107 | 0.088 | −0.013 | 0.071 | −0.123 | 0.179 | 0.284 ** | 0.105 | −0.108 | 0.135 | ||||||

| 22 | If I were financially secure, I would continue my current line of work even if I were no longer being paid. | 0.272 ** | 0.203 | 0.203 | 0.213 * | −0.304 ** | 0.233 * | 0.211 * | 0.173 | 0.292 ** | 0.428 ** | −0.165 | 0.246 * | −0.102 | −0.024 | 0.067 | 0.326 ** | 0.376 ** | 0.470 ** | −0.075 | −0.253 * | 0.230 * | |||||

| 23 | When I am not at work, I don’t think much about my job. | 0.190 | 0.192 | 0.220 * | 0.249 * | −0.279 ** | 0.212 * | 0.261 * | 0.223 * | 0.071 | 0.040 | 0.043 | −0.035 | −0.150 | −0.411 ** | 0.078 | 0.129 | 0.059 | 0.027 | 0.106 | 0.022 | 0.010 | 0.132 | ||||

| 24 | I see my work as a necessity of life, as much as breathing or sleeping. | 0.010 | −0.086 | 0.069 | 0.058 | 0.012 | −0.058 | 0.092 | −0.148 | −0.134 | 0.066 | −0.040 | −0.060 | 0.001 | 0.214 * | 0.198 | 0.108 | 0.073 | −0.006 | 0.080 | 0.049 | 0.046 | 0.144 | −0.151 | |||

| 25 | I never take my work home with me. | 0.096 | 0.109 | 0.197 | 0.260 * | −0.108 | 0.196 | 0.188 | 0.142 | 0.027 | 0.111 | 0.028 | 0.072 | −0.084 | −0.438 ** | −0.010 | 0.093 | 0.095 | 0.040 | 0.197 | 0.070 | −0.043 | 0.110 | 0.474 ** | −0.073 | ||

| 26 | My work is one of the most important things in my life. | 0.050 | 0.139 | 0.005 | 0.156 | –0.015 | 0.165 | 0.063 | 0.094 | 0.155 | 0.156 | –0.009 | 0.193 | 0.082 | 0.094 | 0.119 | 0.008 | 0.151 | 0.343 ** | 0.004 | –0.130 | –0.070 | 0.215 * | –0.357 ** | 0.068 | –0.166 | |

| 27 | I would not encourage young people to follow my kind of work. | 0.117 | −0.137 | −0.270 ** | −0.226 * | 0.199 | −0.252 * | −0.174 | −0.324 ** | −0.155 | −0.494 ** | 0.198 | −0.231 * | 0.229 * | 0.139 | −0.078 | −0.526 ** | −0.391 ** | −0.371 ** | 0.006 | 0.070 | −0.220 * | −0.219 * | −0.040 | −0.117 | −0.053 | −0.012 |

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). * Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

References

- Alonderiene, Rasa, and Monika Majauskaite. 2016. Leadership style and job satisfaction in higher education institutions. International Journal of Educational Management 30: 140–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, Blake. 2001. Role Transitions in Organizational Life: An Identity-Based Perspective. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Asma, Yazmin. 2023. The effect of job satisfaction on work accidents: Empirical study in Algerian electricity and gas company—Hassi Messaoud. Business Ethics and Leadership 7: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Arnold, and Evangelina Demerouti. 2007. The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology 22: 309–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, Teresa, Guy Roman, Michel Khan, Min Lee, Saul Sahbaz, Leslie Duthely, Arnold Knippenberg, María Macias-Burgos, Albert Davidson, Chai Scaramutti, and et al. 2023. What is well-being? A scoping review of the conceptual and operational definitions of well-being. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science 7: e227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beddow, Helen. 2018. Women’s leadership and well-being: Incorporating mindfulness into leadership development programs. Development and Learning in Organizations 33: 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkinshaw, Paula, and Kate White. 2017. Fixing the Women or Fixing Universities: Women in HE Leadership. Administrative Sciences 7: 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-García, Iciar. 2020. The Female Way to Happiness at Work: Happiness for Women and Organisations. In The Pursuit of Happiness and the Traditions of Wisdom. Cham: Springer, pp. 559–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroline, Ngoci, Caleb Ogbogo, and Nadine Clarion. 2022. Job autonomy, workload and home-work conflict as predictors of job satisfaction among employed women in academia. European Journal of Educational Management 5: 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerci, Paul, and Debrin Dumludag. 2019. Life Satisfaction and Job Satisfaction among University Faculty: The Impact of Working Conditions, Academic Performance and Relative Income. Social Indicators Research 147: 785–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Tarrillo, Javier. 2023. Effect of servant leadership on happiness at work of university teachers: The mediating role of emotional salary. Problems and Perspectives in Management 21: 449–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuesta-Valiño, Pablo. 2021. Happiness Management. A Social Well-being multiplier. Social Marketing and Organizational Communication, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demircioglu, Emine. 2014. Organization Performance and Happiness in the Context of Leadership Behavior (Case Study Based on Psychological Well-Beings). MPRA Paper No. 61484. Munich: University Library of Munich. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/61484/1/MPRA_paper_61484.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Horoub, Irman, and Payar Zargar. 2022. Empowering leadership and job satisfaction of academic staff in Palestinian universities: Implications of leader-member exchange and trust in leader. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 1065545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judge, Timothi, Carl Thoresen, Joyce Bono, and Greg Patton. 2001. The job satisfaction–job performance relationship: A qualitative and quantitative review. Psychological Bulletin 127: 376–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kossek, Ellen, Boris Baltes, and Rusell Matthews. 2011. How work-family research can finally have an impact in organizations. Industrial and Organizational Psychology 4: 352–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristof-Brown, Amy, Ryan Zimmerman, and Eren Johnson. 2005. Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of person-job, person-organization, person-group, and person-supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology 58: 281–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadev, Bhanu, Sumit Kundu, Manish Pandey, Nan Mishra, and Ankit Adarsh. 2023. An assessment of self-rated life satisfaction and its correlates with physical, mental and social health status among older adults in India. Dental Science Reports 13: 9117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merma-Molina, Gladys, Melina Urrea-Solano, Sandra Baena-Morales, and Diego Gavilán-Martín. 2022. The satisfactions, contributions, and opportunities of women academics in the framework of sustainable leadership: A case study. Sustainability 14: 8937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milhouse, Vanessa. 2006. Women, Organizational Development, and the New Science of Happiness. Advances in Developing Human Resources 21: 276–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugira, Arnold. 2022. Leadership Perspective Employee Satisfaction Analysis. Journal of Management and Human Resources 2: 127–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nani, Fransica, Ida Hamidah, Ray Ketut, and Riyan Sudiarditha. 2024. Uncovering research clusters in job satisfaction and organizational commitment: A VOS viewer approach. International Journal of Research and Review 11: 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhanunni, Anita, Theo Pretorius, and Sharief Isaacs. 2023. Satisfied with life? The protective function of life satisfaction in the relationship between perceived stress and negative mental health outcomes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20: 6777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raime, Suhaila, Mohd Shamsudin, Roshiri Hashim, and Nurul Abd. 2022. Perceived leaders’ empathy, recognition, monetary compensation and employees’ happiness among universities’ academicians. International Journal of Advanced Research in Education and Society 4: 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohit, Karthik, Ravi Krishnan, Paul Antony, Rajesh Bh, Sowmya Padmapriya, and Umesh Vasudevan. 2023. A predictive modelling of factors influencing job satisfaction through a CNN-BiGRU algorithm. Paper presented at the 2023 International Conference on Self Sustainable Artificial Intelligence Systems (ICSSAS), Erode, India, October 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rubino, Rusmin, Arif Sikumbang, Sirojul Kholil, and Bachtial Helmi. 2022. Leaders’ Personal Communication and the Job Satisfaction of Private Higher Education Employees. Khazanah Social 4: 567–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Vallina, Andres. 2018. Liderazgo femenino y felicidad en el trabajo: El papel mediador del intercambio líder-colaborador. Búsqueda 5: 146–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, Abdul, Michael Muchiri, and Saqib Shahid. 2022. Investigating leadership and employee well-being in higher education. Personnel Review 51: 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnurr, Stephanie. 2008. Surviving in a man’s world with a sense of humour: An analysis of women leaders’ use of humour at work. Leadership 4: 299–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiyowati, Ninik, and Istif Irtaji. 2017. Happiness in Higher Education Leader. Journal of Management and Marketing Review 2: 136–41. Available online: http://gatrenterprise.com/GATRJournals/pdf_files/JMMR%20Vol%202(3)/20.Ninik-Setiyowati-JMMR-2(3)-2017.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2024). [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, Sabine. 2012. Psychological detachment from work during leisure time: The benefits of mentally disengaging from work. Current Directions in Psychological Science 21: 114–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strukova, Anna, and Kira Polivanova. 2023. Well-Being in Education: Modern Theories, Historical Context, Empirical Studies. Available online: https://psyjournals.ru/en/journals/jmfp/archive/2023_n3/Strukova_Polivanova (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Wang, Juhuan, and Marina Milyavskaya. 2020. Simple pleasures: How goal-aligned behaviors relate to state happiness. Current Opinion in Psychology 32: 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).