Exploring Purpose-Driven Leadership: Theoretical Foundations, Mechanisms, and Impacts in Organizational Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

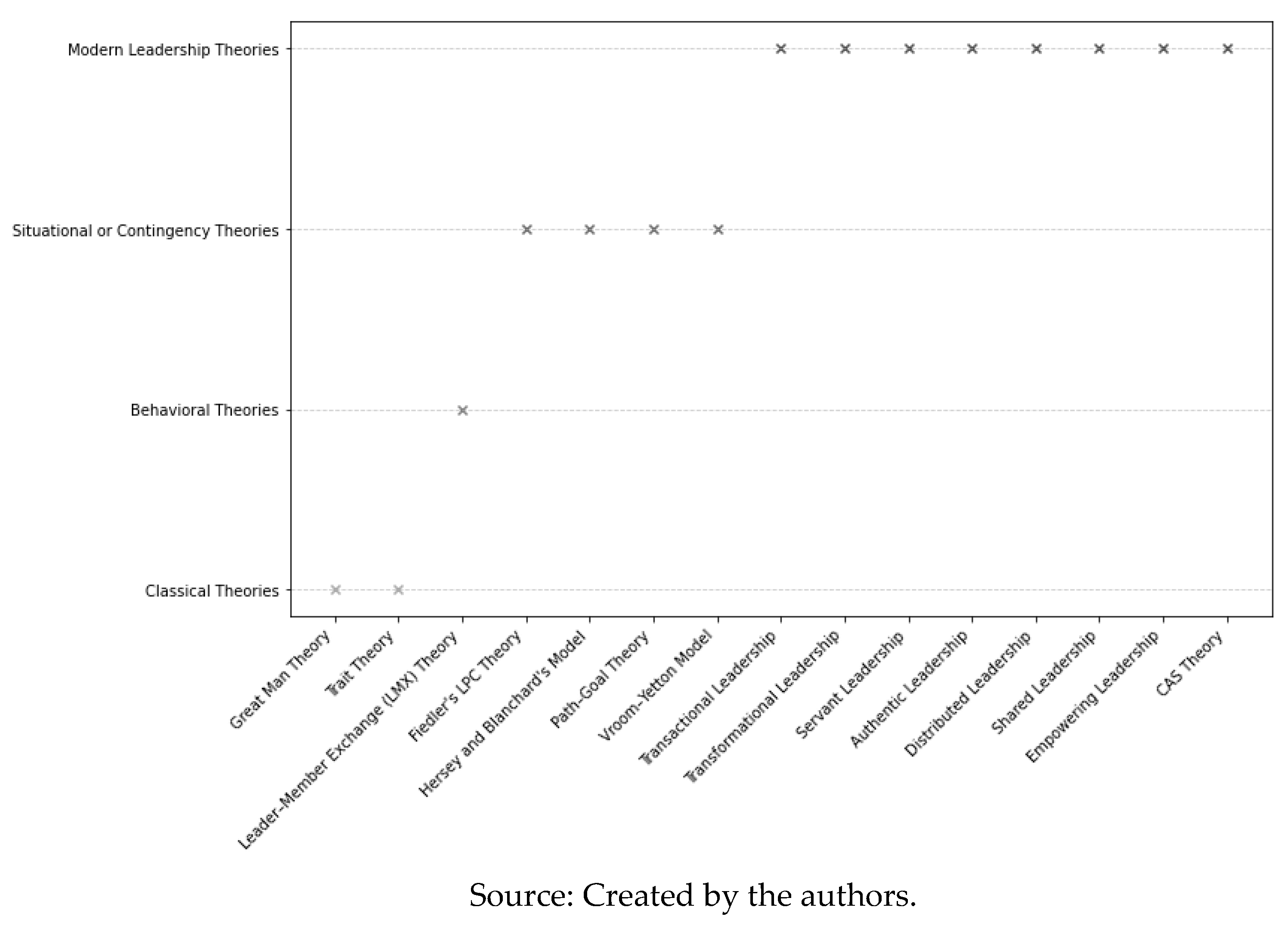

2. Theoretical Perspectives on Leadership: An Evolutionary Analysis

3. Purpose-Driven Leadership: A New Perspective on Leadership

4. Methodology

- 1.

- Population (P): Leaders and organizations adopting purpose-driven approaches.

- 2.

- Intervention (I): Implementation of Purpose-Driven Leadership strategies.

- 3.

- Comparison (C): Examination of how possible moderators and mediators influence the effectiveness of Purpose-Driven Leadership.

- 4.

- Outcomes (O):

- Conceptualization of Purpose-Driven Leadership.

- Importance of Purpose-Driven Leadership in contemporary research and practice.

- Theoretical foundations of Purpose-Driven Leadership.

- Mechanisms and impacts of Purpose-Driven Leadership.

- The role of purpose in navigating times of VUCA.

- Measurement approaches for purpose in leadership.

- 5.

- Study design (S): Theoretical and empirical studies.

5. Findings

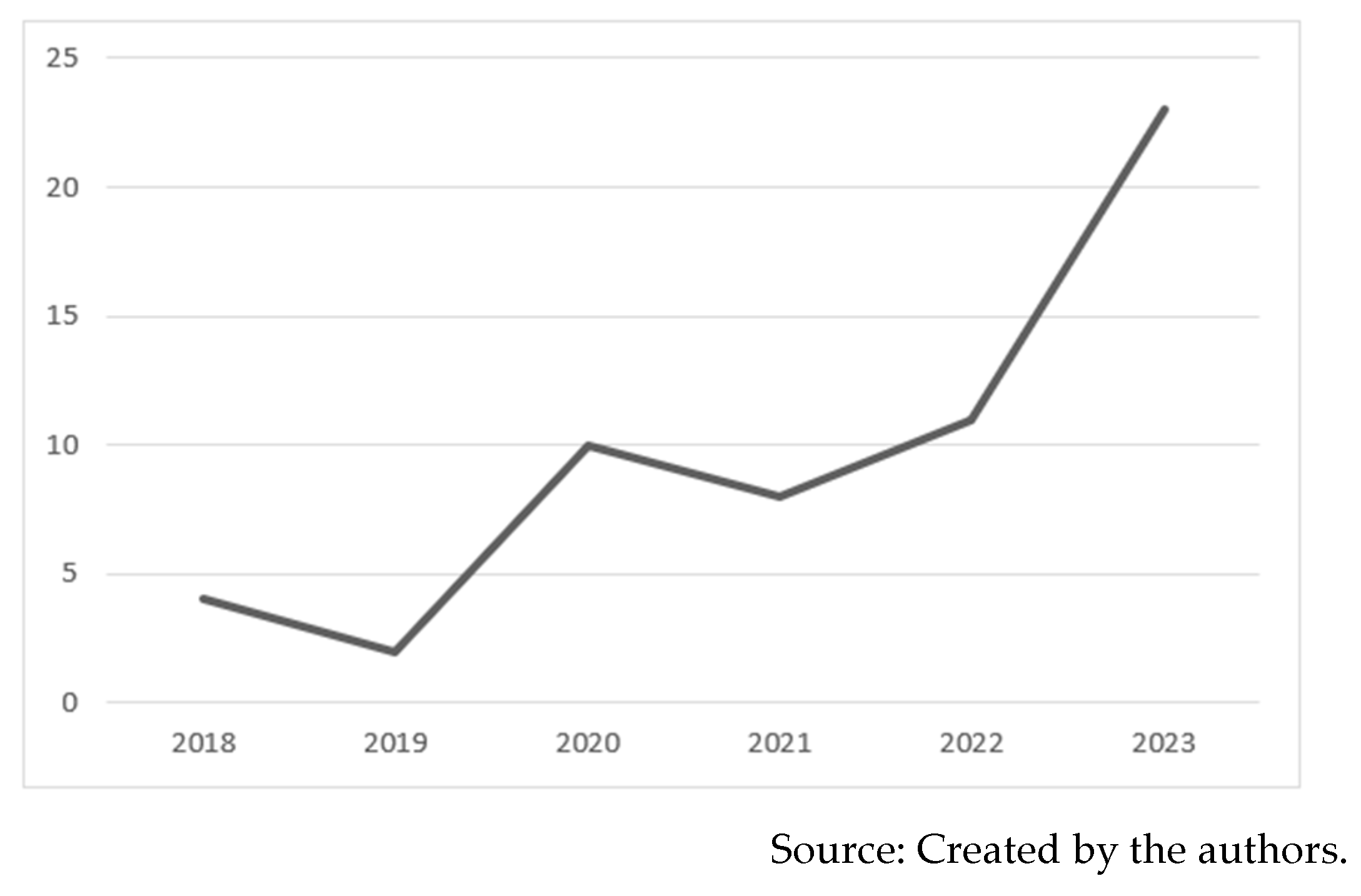

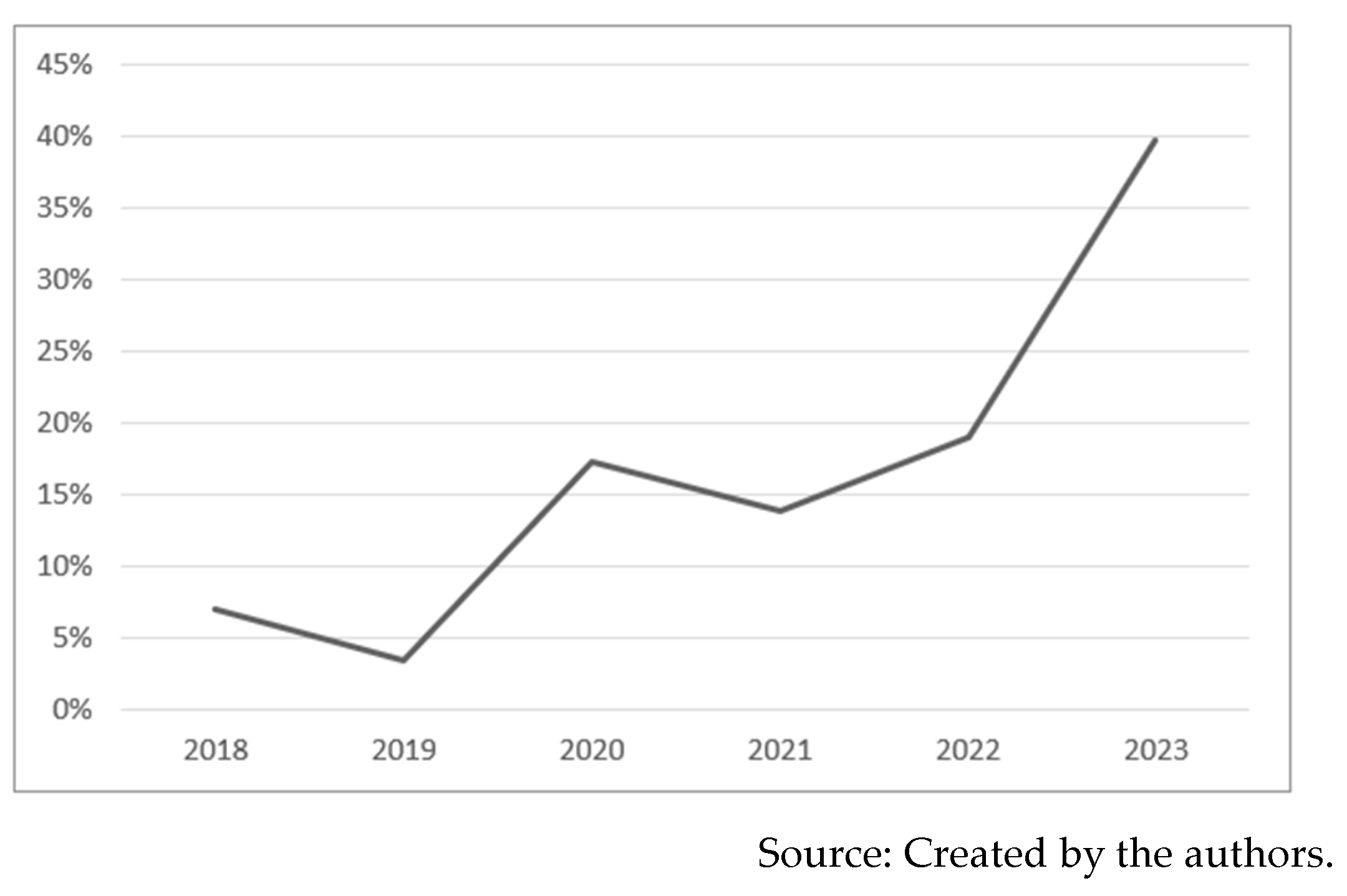

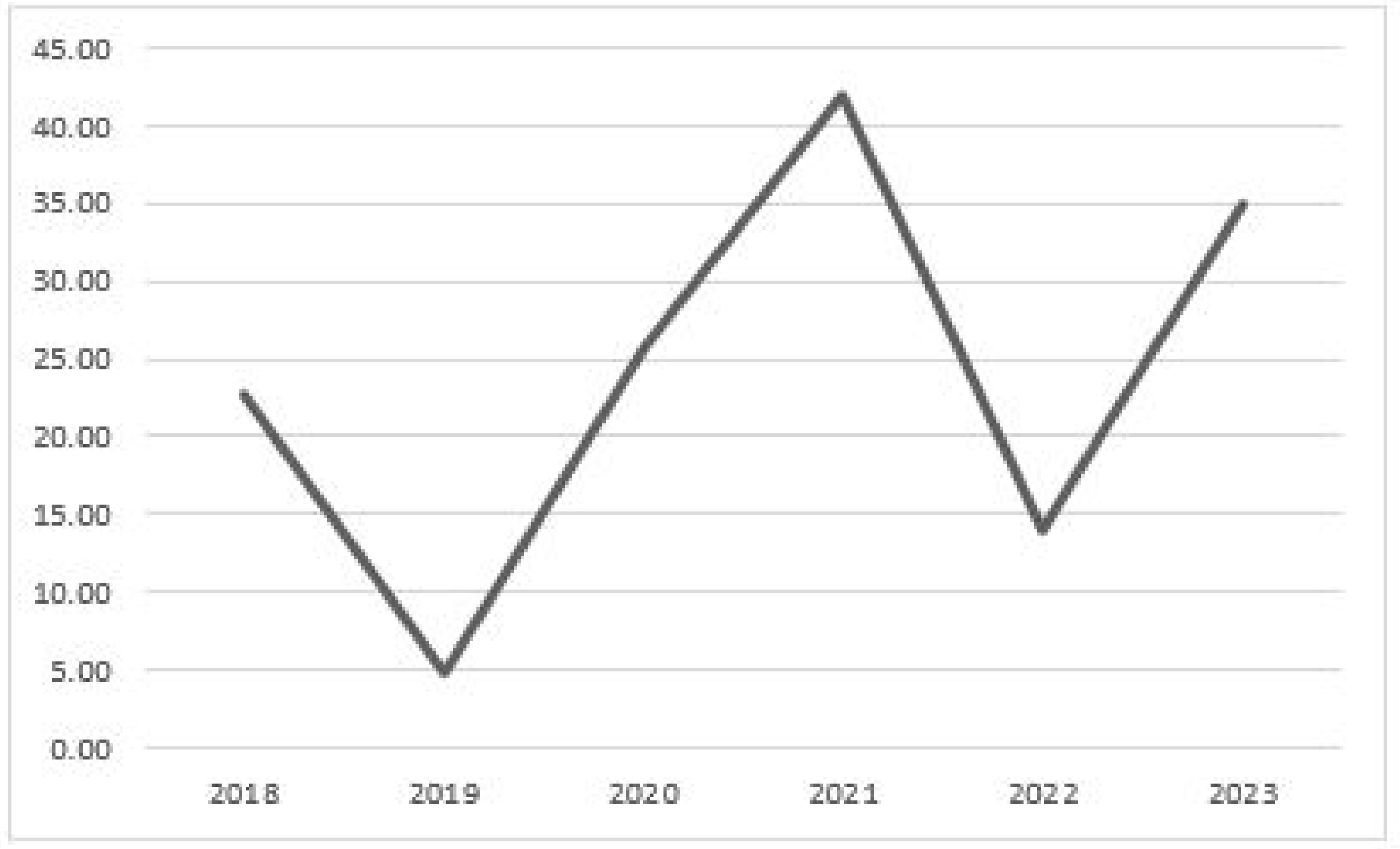

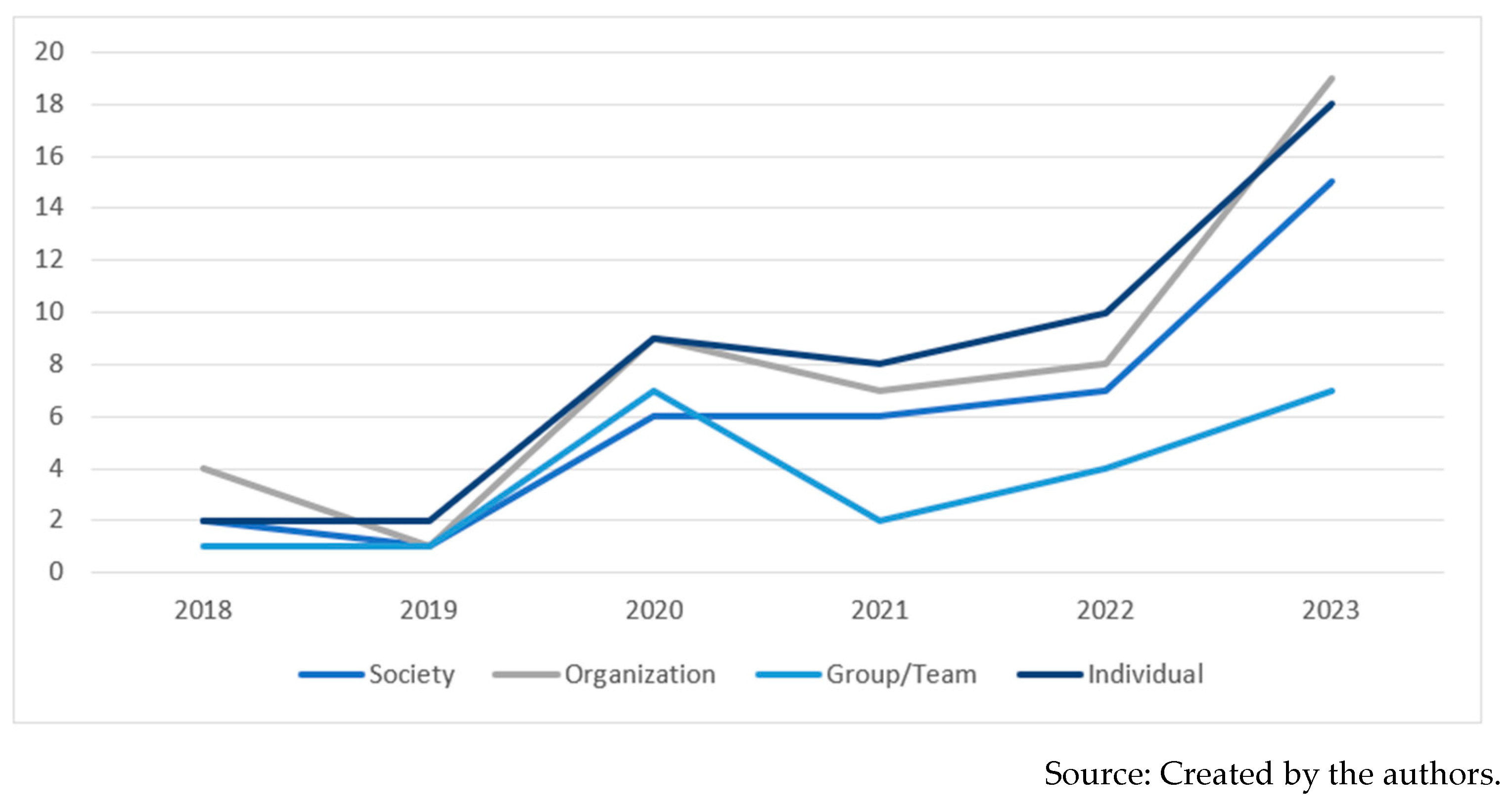

5.1. Purpose-Driven Leadership Research Landscape

5.2. Purpose, Organizational Purpose, and Purpose-Driven Leadership

- Consistency: Purpose does not manifest as a fleeting intention but is grounded in its enduring nature (Gavarkovs et al. 2023; Jasinenko and Steuber 2023; Knippenberg 2020). Demonstrating resilience against ephemeral shifts in external conditions or situational variances, purpose consistently maintains its vigor and steadfastness (Rindova and Martins 2023; Trachik et al. 2020). It acts as a constant lodestar amid the dynamic terrains of both personal and professional spheres (Bhattacharya et al. 2023; Qin et al. 2022; Rindova and Martins 2023).

- Generality: In contradistinction to a limited, task-centric objective, purpose is distinguished by its comprehensive scope (By 2021; Gavarkovs et al. 2023; Jasinenko and Steuber 2023). Instead of being confined to proximate tasks or circumscribed aims, purpose spans a more expansive purview (By 2021; Gavarkovs et al. 2023; Jasinenko and Steuber 2023). This ubiquity of purpose guarantees its applicability across multifarious contexts (By 2021; Gavarkovs et al. 2023; Jasinenko and Steuber 2023).

- Two dimensions:

- -

- Internal Dimension: The internal dimension of purpose refers to the individuals’ intrinsic motivations and impulses, which are connected to their sense of purpose (Crane 2022; Knippenberg 2020). It serves as a source of meaning, supporting the rationale of every decision, direction, or objective delineated (Handa 2023; Jasinenko and Steuber 2023). This introspective aspect emphasizes the congruence and alignment between an individual and their purpose (Gavarkovs et al. 2023; Jasinenko and Steuber 2023).

- -

- External Dimension: Beyond its internal impact, the influence of purpose extends to the external environment, through the efforts generated by the individual within their context (By 2021; Gavarkovs et al. 2023; Handa 2023; Jasinenko and Steuber 2023). This is underpinned by the individual’s commitment to promoting positive change in a broader environment (Ocasio et al. 2023; Qin et al. 2022).

- Daily embodiment and expression: Purpose manifests as a palpable instantiation in quotidian activities since it is part of every decision and action made (By 2021; Jasinenko and Steuber 2023). Such perennial articulation provides consistency and influences daily activities (Bronk et al. 2023; Hurth and Stewart 2022; Ocasio et al. 2023).

5.2.1. Attributes of Purpose-Driven Leadership

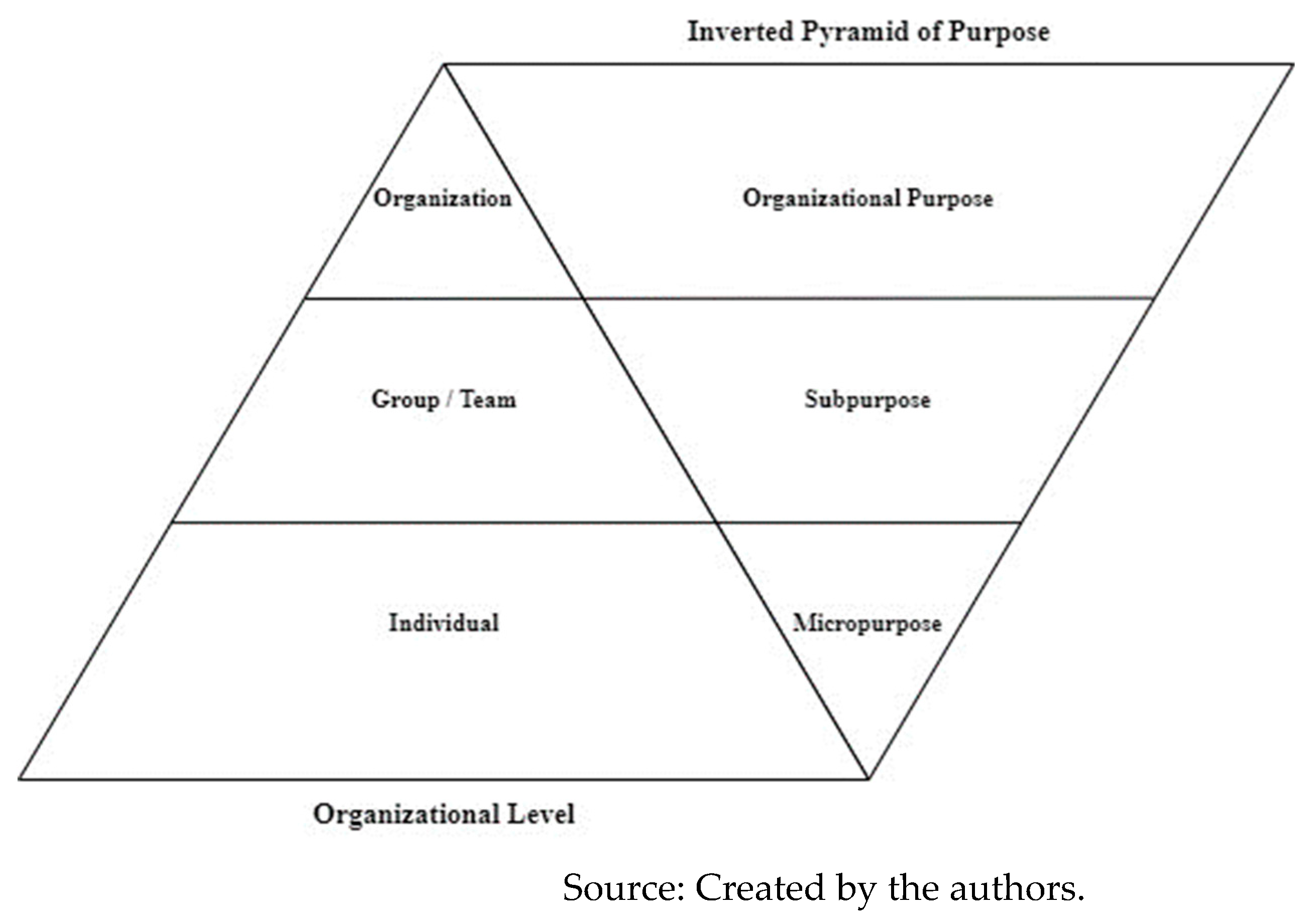

5.2.2. Purpose-Driven Leadership Construct Conceptualization

5.3. Theoretical Foundations of Purpose-Driven Leadership

5.4. Mechanisms and Impacts of Purpose-Driven Leadership

5.4.1. Potential Antecedents

5.4.2. Potential Outcomes

5.4.3. Potential Mediators

5.4.4. Potential Moderatos

5.5. Purpose-Driven Leadership as a Guiding Light

5.6. Measurement Approaches for Purpose-Driven Leadership

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbas, Muhammad, and Raza Ali. 2023. Transformational versus transactional leadership styles and project success: A meta-analytic review. European Management Journal 41: 125–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adobor, Henry, William Phanuel Kofi Darbi, and Obi Berko O. Damoah. 2021. Strategy in the era of “swans”: The role of strategic leadership under uncertainty and unpredictability. Journal of Strategy and Management. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguileta-Clemente, Carmen López, Julinda Molares-Cardoso, and V. Badenes Plá. 2023. The purpose as a dynamizer of corporate culture and value generator: Analysis of the websites of IBEX-35 Spanish companies Carmen. Revista Internacional de Relaciones Públicas 13: 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahinful, Gabriel Sam, Jeff Danquah Boakye, and Nana Dwomoh Osei Bempah. 2023. Determinants of SMEs’ financial performance: Evidence from an emerging economy. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship 35: 362–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almandoz, Juan. 2023. Inside-out and outside-in perspectives on corporate purpose. Strategy Science 8: 139–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amah, Okechukwu Ethelbert, and Kabiru Oyetuunde. 2020. The effect of servant leadership on employee turnover in SMEs in Nigeria: The role of career growth potential and employee voice. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 27: 885–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anshori, Lutfi Isa, Purnamie Titisari, Sri Wahyu Lelly Hana Setyanti, Raden Andi Sularso Handriyono, and Arnis Budi Susanto. 2023. The Influence of Servant Leadership on Motivation, Work Engagement, Job Satisfaction and Teacher Performance of Vocational Hight School Teachers in Jember City. Quality—Access to Success 24: 261–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakis, John, George Banks, Nicolas Bastardoz, Michael Cole, David Day, Alice Eagly, Olga Epitropaki, Roseanne Foti, William Gardner, Alex Haslam, and et al. 2019. The Leadership Quarterly: State of the journal. The Leadership Quarterly 30: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azungah, Theophilus. 2018. Qualitative research: Deductive and inductive approaches to data analysis. Qualitative Research Journal 18: 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Mayangzong, Xinyi Zheng, Xu Huang, Tiantian Jing, Chenhao Yu, Sisi Li, and Zhiruo Zhang. 2023. How serving helps leading: Mediators between servant leadership and affective commitment. Frontiers in Psychology 14: 1170490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baquero, Asier. 2023. Authentic leadership, employee work engagement, trust in the leader, and workplace well-being: A moderated mediation model. Psychology Research and Behavior Management 16: 1403–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnard, Caa Iaa. 1938. The Functions of the Executive. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, Bernard. 1985. Leadership and Performance: Beyond Expectations. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berraies, Sarra. 2023. Mediating effects of employees’ eudaimonic and hedonic well-being between distributed leadership and ambidextrous innovation: Does employees’ age matter? European Journal of Innovation Management 26: 1271–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C. B., Sankar Sen, Laura Marie Edinger-Schons, and Michael Neureiter. 2023. Corporate Purpose and Employee Sustainability Behaviors. Journal of Business Ethics 183: 963–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brendel, William, Sang Won Byun, and Mi Hee Park. 2023. Ways of Being: Assessing Presence and Purpose at Work. Journal of Management Spirituality & Religion 20: 53–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronk, Kendall Cotton, Caleb Mitchell, Elyse Postlewaite, Anne Colby, William Damon, and Zach Swanson. 2023. Family purpose: An empirical investigation of collective purpose. The Journal of Positive Psychology 19: 662–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brower, Holly H., F. David Schoorman, and Hwee Hoon Tan. 2000. A model of relational leadership. The Leadership Quarterly 11: 227–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Ryan P., Lebena Varghese, Sarah Sullivan, and Sandy Parsons. 2021. The Impact of Professional Coaching on Emerging Leaders. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring 19: 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunderson, Stuart, and Anjan V. Thakor. 2022. Higher purpose, banking and stability. Journal of Banking & Finance 140: 106138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, James MacGregor. 1978. Leadership. Manhattan: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- By, Rune Todnem. 2021. Leadership: In pursuit of purpose. Journal of Change Management 21: 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, Cam, and Linda A. Hayes. 2016. Self-efficacy and self-awareness: Moral insights to increased leader effectiveness. Journal of Management Development 35: 1163–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavesi, Alice, and Eliana Minelli. 2022. Servant leadership and employee engagement: A qualitative study. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal 34: 413–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capon, Noel, John Farley, and Scott Hoenig. 1990. Determinants of Financial Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Management Science 36: 1143–59. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2632657 (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Castillo, Elizabeth A., and Mai P. Trinh. 2019. Catalyzing capacity: Absorptive, adaptive, and generative leadership. Journal of Organizational Change Management 32: 356–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavazotte, Flavia, Sylvia Freitas Mello, and Lucia B. Oliveira. 2020. Expatriate’s engagement and burnout: The role of purpose-oriented leadership and cultural intelligence. Journal of Global Mobility: The Home of Expatriate Management Research 9: 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Katherine S. 2023. Purpose and process: Power, equity, and agenda setting. New Directions for Student Leadership 2023: 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen-Salem, Amanda, Marco Tulio F. Zanini, Fred O. Walumbwa, Ronaldo Parente, Daniel M. Peat, and Jaclyn Perrmann-graham. 2021. Communal solidarity in extreme environments: The role of servant leadership and social resources in building serving culture and service performance. Journal of Business Research 135: 829–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, Thomas. 2020. The contest on corporate purpose: Why Lynn Stout was right and Milton Friedman was wrong. Accounting, Economics and Law: A Convivium 10: 20200145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cline, Michaela, Paige Roberts, Timothy Werlau, Paloma Hauser, and Cheryl Smith-Miller. 2022. Three good things: Promote work–life balance, reduce burnout, enhance reflection among newly licensed RNs. Nursing Forum 57: 1390–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consoli, Sal. 2021. Uncovering the hidden face of narrative analysis: A reflexive perspective through MAXQDA. System 102: 102611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordoba, Emmeline Lagunes, Suzanne Shale, Rachel Clare Evans, and Derek Tracy. 2022. Time to get serious about distributed leadership: Lessons to learn for promoting leadership development for non-consultant career grade doctors in the UK. BMJ Leader 6: 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabtree, Benjamin F., Jenna Howard, William L. Miller, DeANN Cromp, Clarissa Hsu, Katie Coleman, Brian Austin, Margaret Flinter, Leah Tuzzio, and Edward H. Wagner. 2020. Leading Innovative Practice: Leadership Attributes in LEAP Practices. The Milbank Quarterly 98: 399–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, Bret. 2022. Eudaimonia in Crisis: How Ethical Purpose Finding Transforms Crisis. Humanistic Management Journal 7: 391–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofaro, Matheo, Christopher Neck, Pier Luigi Giardino, and Christopher B. Neck. 2023. Self and shared leadership in decision quality: A tale of two sides. Management Decision 61: 2541–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, Mohit Ranjan, Pramod Pathak, and Mohit Ranjan Das. 2018. Spirituality at Workplace: A Report from Ground Zero. Purushartha—A Journal of Management Ethics and Spirituality 11: 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhamija, Pavitra, Andrea Chiarini, and Shara Shapla. 2023. Technology and leadership styles: A review of trends between 2003 and 2021. The TQM Journal 35: 210–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, Kiril. 2022. Organizational Leadership through the Massive Transformative Purpose. Economic Alternatives 28: 318–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorasamy, Nirmala. 2010. Enhancing an ethical culture through purpose-directed leadership for improved public service delivery: A case for South Africa. African Journal of Business Management 4: 56–63. Available online: http://search.proquest.com/docview/1663906542?accountid=40690%5Cnhttp://link.periodicos.capes.gov.br/sfxlcl41?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:journal&genre=article&sid=ProQ:ProQ%3Apqrl&atitle=Enhancing+an+ethical+culture+through+purpo (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Edgar, Stacey. 2023. Artisan social enterprises in Zambia: Women leveraging purpose to scale impact. Social Enterprise Journal 20: 140–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenschmidt, Eve, Elina Kuusisto, Katrin Poom-Valickis, and Kirsi Tirri. 2019. Virtues that create purpose for ethical leadership: Exemplary principals from Estonia and Finland. Journal of Beliefs & Values 40: 433–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, Satu, and Helvi Kyngäs. 2008. The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing 62: 107–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enslin, Carla, Michelle Wolfswinkel, and Marlize Terblanche-Smit. 2023. Responsible leadership through purpose-driven brand building: Guidelines for leaders in Africa. South African Journal of Business Management 53: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, Fred E. 1964. A Contingency Model of Leadership Effectiveness. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 1: 149–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzsimmons, Lexis Bajalia, Yufan Sunny Qin, and Eve R. Heffron. 2022. Purpose vs. mission vs. vision: Persuasive appeals and components in corporate statements. Journal of Communication Management 26: 207–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischer, Holger. 2021. Corporate Purpose: A Management Concept and its Implications for Company Law. SSRN Electronic Journal 18: 161–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Lihua, Zhiying Liu, and Suqin Liao. 2018. Is distributed leadership a driving factor of innovation ambidexterity? An empirical study with mediating and moderating effects. Leadership & Organization Development Journal 39: 388–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Qinghua, Abdul Aziz Abdul Rahman, Hui Jiang, Jaward Abbas, and Ubaldo Comite. 2022. Sustainable Supply Chain and Business Performance: The Impact of Strategy, Network Design, Information Systems, and Organizational Structure. Sustainability 14: 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartenberg, Claudine, and Todd Zenger. 2023. The Firm as a Subsociety: Purpose, Justice, and the Theory of the Firm. Organization Science 34: 1965–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavarkovs, Adam G., Rashmi A. Kusurkar, and Ryan Brydges. 2023. The purpose, adaptability, confidence, and engrossment model: A novel approach for supporting professional trainees’ motivation, engagement, and academic achievement. Frontiers in Education 8: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisler, Cheryl. 2018. Coding for Language Complexity: The Interplay Among Methodological Commitments, Tools, and Workflow in Writing Research. Written Communication 35: 215–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, Alfonso J., Gabriela Bittencourt Gonzalez Mosegui, Rosana Zenezi Moreira, and Mauro J. Eguizabal. 2023. The moderating role of employee proactive behaviour in the relationship between servant leadership and job satisfaction. International Journal of Organizational Analysis 32: 422–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graen, George B., and Mary Uhl-Bien. 1995. Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. The Leadership Quarterly 6: 219–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenleaf, Robert Kiefner. 1977. Servant Leadership: A Journey into the Nature of Legitimate Power and Greatness. Mahwah: Paulist Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gwartz, Evan, and Kirsty Spence. 2020. Conscious capitalism and sport: Exploring higher purpose in a professional sport organization. Sport Management Review 23: 750–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haar, Jarrod M., and Candice Harris. 2023. A moderated mediation study of high performance work systems and insomnia on New Zealand employees: Job burnout mediating and work-life balance moderating. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 34: 68–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, Philip, and Jasna Kovačević. 2022. Mapping the intellectual lineage of educational management, administration and leadership, 1972–2020. Educational Management Administration and Leadership 50: 192–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handa, Manoj Chandra. 2023. The leading wisdom development framework: An integrated roadmap for cultivating a sense of purpose and meaning. Journal of Advanced Academics 34: 32–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartnell, Chad, Amanda Christensen-Salem, Fred O. Walumbwa, Derek Stotler, Flora Chiang, and Thomas A. Birtch. 2023. Manufacturing motivation in the mundane: Servant leadership’s influence on employees’ intrinsic motivation and performance. Journal of Business Ethics 188: 533–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersey, Paul, Kenneth H. Blanchard, and Walter E. Natemeyer. 1979. Situational Leadership, Perception, and the Impact of Power. Group & Organization Studies 4: 418–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, Niamh, Aishling Flaherty, and Patricia Mannix McNamara. 2022. Distributed Leadership: A Scoping Review Mapping Current Empirical Research. Societies 12: 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, Giang Hien, Elisabeth Wilson-Evered, Leonie Lockstone-Binney, and Tuan Trong Luu. 2021. Empowering leadership in hospitality and tourism management: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 33: 4182–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Paul C., Joseph Chacko Chennattuserry, Xiyue Deng, and Margaret M. Hopkins. 2021. Purpose-driven leadership and organizational success: A case of higher educational institutions. Leadership & Organization Development Journal 42: 1004–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurth, Victoria, and Iain S. Stewart. 2022. Re-purposing Universities: The Path to Purpose. Frontiers in Sustainability 2: 762271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingen, Ramon van, Pascale Peters, Melanie De Ruiter, and Henry Robben. 2021. Exploring the meaning of organizational purpose at a new dawn: The development of a conceptual model through expert interviews. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 675543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Jamil Ul, Owais Nazir, and Zillur Rahman. 2023. Sustainably engaging employees in food wastage reduction: A conscious capitalism perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production 389: 136091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itzkovich, Yariv, Sibylle Heilbrunn, and Ana Aleksic. 2020. Full range indeed? The forgotten dark side of leadership. Journal of Management Development 39: 851–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, Kirsten, Monica Bianchi, Rosa Dilae Pereira Costa, Keren Grinberg, Gerardina Harnett, Marie_Louise Luiking, Stefan Nilsson, and Janet Mary Elizabeth Scammell. 2022. Clinical leadership in nursing students: A concept analysis. Nurse Education Today 108: 105173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasinenko, Anna, and Josephina Steuber. 2023. Perceived organizational purpose: Systematic literature review, construct definition, measurement and potential employee outcomes. Journal of Management Studies 60: 1415–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jønsson, Thomas Faurholt, Esther Bahat, and Massimilano Barattucci. 2021. How are empowering leadership, self-efficacy and innovative behavior related to nurses’ agency in distributed leadership in Denmark, Italy and Israel? Journal of Nursing Management 29: 1517–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, Timothy A., Joyce E. Bono, Remus Ilies, and Megan W. Gerhardt. 2002. Personality and leadership: A qualitative and quantitative review. Journal of Applied Psychology 87: 765–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, Sarah. 2023. The promises and perils of corporate purpose. Strategic Science 8: 288–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempster, Steve, and Brad Jackson. 2021. Leadership for What, Why, for Whom and Where? A Responsibility Perspective. Journal of Change Management 21: 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempster, Steve, Marian Iszatt-White, and Matt Brown. 2019. Authenticity in leadership: Reframing relational transparency through the lens of emotional labour. Leadership 15: 319–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Sunmi, Seok Hee Jeong, and Myoung Hee Seo. 2022. Nurses’ ethical leadership and related outcome variables: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Nursing Management 30: 2308–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knippenberg, Daan Vaaaa. 2020. Meaning-based leadership. Organizational Psychology Review 10: 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, Howard K., Cathy C. Tso, Cyra Perry Dougherty, Emily E. Lazowy, Chelsea P. Heberlein, and Fawn A. Phelps. 2023. Exploring the spiritual foundations of public health leadership. Frontiers in Public Health 11: 1210160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konadu, Kingsley, Abigail Opaku Mensah, Samuel Koomson, Ernest Mensah Abraham, Joshua Amuzu, and Joan-Ark Manu Agyapong. 2023. A model for improving the relationship between integrity and work performance. International Journal of Ethics and Systems. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumpulainen, Milka, and Marko Seppänen. 2022. Combining Web of Science and Scopus datasets in citation-based literature study. Scientometrics 127: 5613–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaVoi, Samantha, and Eric Haley. 2021. How Pro-Social Purpose Agencies Define Themselves and Their Value: An Emerging Business Model in the Advertising-Agency World. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 42: 372–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, Crystal, and Dan Weberg. 2023. Leading through times of transformation: Purpose, trust, and co-creation. Nurse Leader 21: 380–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Clif P., and Maryam Aldossari. 2022. “One of these things is not like the others”: The role of authentic leadership in cross-cultural leadership development. Leadership and Organization Development Journal 43: 1252–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Qin, and Lingfeng Yi. 2023. Survival of the fittest: The multiple paths of entrepreneurial leadership driving adaptive innovation in uncertain environment. European Journal of Innovation Management 26: 1150–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, Robert G., Paola Gatti, and Susanna L. M. Chui. 2016. Social-cognitive, relational, and identity-based approaches to leadership. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 136: 119–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losada-Vazquez, Angel. 2022. Organizational learning at purpose-driven enterprise: Action–research model for leadership improvement. Sustainability 14: 1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Shiwen, and Jiseon Ahn. 2023. Assessment of job meaning based on attributes of food-delivery mobile applications. Current Issues in Tourism 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luedi, Markus M. 2022. Leadership in 2022: A perspective. Best Practice & Research Clinical Anaesthesiology 36: 229–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magasi, Chacha. 2021. The role of transformational leadership on employee performance: A perspective of employee empowerment. European Journal of Business and Management Research 6: 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martela, Frank, and Anne B. Pessi. 2018. Significant work is about self-realization and broader purpose: Defining the key dimensions of meaningful work. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, Seth-Aaron, and Nahari Leija. 2023. Distinguishing Servant Leadership from Transactional and Transformational Leadership. Advances in Developing Human Resources 25: 141–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methley, Abigail M., Stephen Campbell, Carolyn Chew-Graham, Rosalind McNally, and Sudeh Cheraghi-Sohi. 2014. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Services Research 14: 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meynhardt, Timo, Josephina Steuber, and Maximilian Feser. 2023. The Leipzig Leadership Model: Measuring leadership orientations. Current Psychology 43: 9005–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, David, Alessandro Liberati, Jennifer Tetzlaff, and Douglas G. Altman. 2009. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine 6: e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouton, Nico. 2019. A literary perspective on the limits of leadership: Tolstoy’s critique of the great man theory. Leadership 15: 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulyani, Sri, Anas A. Salameh, Aan Komariah, Anton Timoshin Nik Alif Amri NikHashim, R. Siti Pupi Fauziah, Mulyaningsih Mulyaningsih, Israr Ahmad, and Sajid Mohy Ul din. 2021. Emotional Regulation as a Remedy for Teacher Burnout in Special Schools: Evaluating School Climate, Teacher’s Work-Life Balance and Children Behavior. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 655850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Julia S., Ying Chen, Tyler J. VanderWeele, and Eric S. Kim. 2022. What makes life purposeful? Identifying the antecedents of a sense of purpose in life using a lagged exposure-wide approach. SSM Population Health 19: 101235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazir, Owais, Jamid Ul, and Zillur Rahman. 2021. Effect of CSR participation on employee sense of purpose and experienced meaningfulness: A self-determination theory perspective. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 46: 123–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Nguyen Thi Thao, Nguyen Phong Nguyen, and Tu Thanh Hoai. 2021. Ethical leadership, corporate social responsibility, firm reputation, and firm performance: A serial mediation model. Heliyon 7: e06809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ocasio, William, Mathew Kraatz, and David Chandler. 2023. Making Sense of Corporate Purpose. Strategy Science 8: 123–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunfowora, Babatunde, Meena Andiappan, Madelynn Stackhouse, and Christianne Varty. 2023. CEO ethical leadership as a unique source of substantive and rhetorical ethical signals for attracting job seekers: The moderating role of job seekers’ moral identity. Journal of Organizational Behavior 44: 1380–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olin, Karolina, Charlotte Klinga, Mirjam Ekstedt, and Karin Pukk-Härenstam. 2023. Exploring everyday work as a dynamic non-event and adaptations to manage safety in intraoperative anaesthesia care: An interview study. BMC Health Services Research 23: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, Matthew J., Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M. Tetzlaff, Ellie A. Akl, Sue E. Brennan, and et al. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panojan, Pavalakanthan, Kanchana K. S. Perera, and Rajaratnam Dilakshan. 2022. Work-life balance of professional quantity surveyors engaged in the construction industry. International Journal of Construction Management 22: 751–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pate, Larry B., and Donald C. Heiman. 1987. A Test of the Vroom-Yetton Decision Model in Seven Field Settings. Personnel Review 16: 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, Robin, Daan Westra, Arno J. A. van Raak, and Dirk Ruwaard. 2023. So Happy Together: A Review of the Literature on the Determinants of Effectiveness of Purpose-Oriented Networks in Health Care. Medical Care Research and Review 80: 266–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowar-Sulej, Katarzyna, and Qaisar Iqbal. 2023. Leadership styles and sustainable performance: A systematic literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production 382: 134600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponting, Sandra SunAh. 2020. Organizational identity change: Impacts on hotel leadership and employee wellbeing. The Service Industries Journal 40: 6–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Martos, Manuel, Leire Gartzia, José María Augusto-Landa, and Esther Lopez-Zafra. 2023. Transformational leadership and emotional intelligence: Allies in the development of organizational affective commitment from a multilevel perspective and time-lagged data. In Review of Managerial Science. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Yufan Sunny, Marica W. DiStaso, Alexis Fitzsimmons, Eve Heffron, and Linjuan Rita Men. 2022. How purpose-driven organizations influenced corporate actions and employee trust during the global COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Strategic Communication 16: 426–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, Puneet. 2020. The rising interest in workplace spirituality: Micro, meso and macro perspectives. Purushartha 13: 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashmi, Kumari, and Aakanksha Kataria. 2022. Work–life balance: A systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 42: 1028–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, Carlos, and Miquel Bastons. 2018. Three dimensions of effective mission implementation. Long Range Planning 51: 580–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindova, Violina P., and Luis L. Martins. 2023. Moral imagination, the collective desirable, and strategic purpose. Strategy Science 8: 170–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, Dennis Caaa. 2020. Discovering Purpose: A Life-Long Journey. New Directions for Student Leadership 2020: 123–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, Hector, Michael Pirson, and Roy Suddaby. 2021. Business with Purpose and the Purpose of Business Schools: Re-Imagining Capitalism in a Post Pandemic World: A Conversation with Jay Coen Gilbert, Raymond Miles, Christian Felber, Raj Sisodia, Paul Adler, and Charles Wookey. Journal of Management Inquiry 30: 354–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salhieh, Loay, Ala’a Mehiar, Ismail Abushaikha, Hendrik Reefke, and Loay Bani-Ismail. 2023. The strategic fit between strategic purchasing and purchasing involvement: The moderating role of leadership styles. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management 41: 559–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, Uzma, Muhammad Aamir, Yu Bichao, and Zhongwen Chen. 2023. Authentic leadership, perceived organizational support, and psychological capital: Implications for job performance in the education sector. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 1084963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarwar, Uzma, Samina Zamir, Kiran Fazal, Yang Hong, and Qi Zhan Yong. 2022. Impact of leadership styles on innovative performance of female leaders in Pakistani Universities. PLoS ONE 17: e0266956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavenato, Martin, and Frances Chu. 2021. PICO: What it is and what it is not. Nurse Education in Practice 56: 103194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selznick, Philips. 1957. Leadership in Administration: A Sociological Interpretation. In American Sociological Review. Berkeley: University of California Press, vol. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Shahab, Moh Ali, Agus Sobari, and Udin Udin. 2018. Empowering Leadership and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Mediating Roles of Psychological Empowerment and Emotional Intelligence in Medical Service Industry. International Journal of Economics and Business Administration VI: 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoukat, Muhammad Haroon, Syed Asim Shah, and Dilnaz Muneeb. 2023. Shared leadership and team performance in health care: How intellectual capital and team learning intervene in this relationship. The Learning Organization 30: 426–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Sanjay Kumar, Manlio Del Giudice, Shlomo Y. Tarba, and Paola De Bernardi. 2022. Top Management Team Shared Leadership, Market-Oriented Culture, Innovation Capability, and Firm Performance. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 69: 2544–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, Hilke, and Ganga S. Dhanesh. 2023. Care-based relationship management during remote work in a crisis: Empathy, purpose, and diversity climate as emergent employee-organization relational maintenance strategies. Public Relations Review 49: 102371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Ronny, and Ferdi Antonio. 2022. New insights on employee adaptive performance during the COVID-19 pandemic: Empirical evidence from Indonesia. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation 18: 175–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, Kaitlyn, Tatiana Penconek, Bruna Moreno Dias, Greta G. Cummings, and Andrea Bernardes. 2023. Authentic leadership, organizational culture and the effects of hospital quality management practices on quality of care and patient satisfaction. Journal of Advanced Nursing 79: 3102–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Geir, and Lars Glasø. 2018. Situational leadership theory: A test from a leader-follower congruence approach. Leadership & Organization Development Journal 39: 574–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trachik, Benjamin, Emma H. Moscardini, Michelle L. Ganulin, Jen L. McDonald, Ashlee B. McKeon, Michael N. Dretsch, Raymond P. Tucker, and Walter J. Sowden. 2022. Perceptions of purpose, cohesion, and military leadership: A path analysis of potential primary prevention targets to mitigate suicidal ideation. Military Psychology 34: 366–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trachik, Benjamim, Raymond P. Tucker, Michelle L. Ganulin, Julie C. Merrill, Matthew L. LoPresti, Oscar A. Cabrera, and Michael N. Dretsch. 2020. Leader provided purpose: Military leadership behavior and its association with suicidal ideation. Psychiatry Research 285: 112722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuin, Lars Van, Wilmar B. Schaufeli, Anja Van den Broeck, and Williem van Rhenen. 2020. A corporate purpose as an antecedent to employee motivation and work engagement. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 572343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandagriff, Susan. 2023. Do We Know What We Publish? Comparing Self-Reported Publication Data to Scopus and Web of Science. Serials Review 49: 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VERBI Software. 2022. MAXQDA 2022 [Computer Software]. Available online: https://www.maxqda.com (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Vugt, Mark, and Christopher Rueden. 2020. From genes to minds to cultures: Evolutionary approaches to leadership. The Leadership Quarterly 31: 101404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, Dayna Herbert, and Rebecca J. Reichard. 2020. On Purpose: Leader Self-Development and the Meaning of Purposeful Engagement. Journal of Leadership Studies 14: 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Oliver. 2018. Restorying the Purpose of Business: An Interpretation of the Agenda of the UN Global Compact. African Journal of Business Ethics 12: 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xhemajli, Ariana, Mimoza Luta, and Emin Neziraj. 2022. Applying distributed leadership in micro and small enterprises of kosovo. WSEAS Transactions On Business And Economics 19: 1860–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccaro, Stephen J. 2007. Trait-based perspectives of leadership. American Psychologist 62: 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Liming, Miles Yang, Zhenyuan Wang, and Grant Michelson. 2023. Trends in the Dynamic Evolution of Corporate Social Responsibility and Leadership: A Literature Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Journal of Business Ethics 182: 135–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Jinlong, Zhenyu Liao, Kai Chi Yam, and Russell E. Johnson. 2018. Shared leadership: A state-of-the-art review and future research agenda. Journal of Organizational Behavior 39: 834–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Journal | Publications per Journal | Journal | Citations per Journal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy Science | 4 | Frontiers in Psychology | 143 |

| Frontiers in Psychology | 3 | Journal of Change Management | 49 |

| Journal of Change Management | 2 | Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management | 44 |

| New directions for student leadership | 2 | Organizational Psychology Review | 24 |

| Purushartha | 2 | Service Industries Journal | 24 |

| Aspect | Individual Purpose | Organizational Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Nature | A consistent and generalized intention to do something that is simultaneously personally meaningful and holds relevance to the world (Gavarkovs et al. 2023; Jasinenko and Steuber 2023). It acts as a foundational and central self-organizing life aim, guiding and stimulating goals and behaviors (By 2021; Gavarkovs et al. 2023), and providing a sense of meaning (Brendel et al. 2023; Jasinenko and Steuber 2023). | The foundational reason why the organization exists (Bhattacharya et al. 2023; Dimitrov 2022; Kaplan 2023) that guides all the activities (Fitzsimmons et al. 2022; Hong et al. 2021), provides direction (Ingen et al. 2021; Tuin et al. 2020) and unification (Almandoz 2023; Ingen et al. 2021), and drives meaning (Kaplan 2023; Rindova and Martins 2023). It is rooted rooted in the deepest level of an organization’s identity (Hurth and Stewart 2022; Ponting 2020). |

| Core components | 1. Consistency: Enduring nature (Gavarkovs et al. 2023; Jasinenko and Steuber 2023; Knippenberg 2020), and resilience against changes (Rindova and Martins 2023; Trachik et al. 2020). 2. Generality: Comprehensive scope, applicable in many contexts (By 2021; Gavarkovs et al. 2023; Jasinenko and Steuber 2023). 3. Embodiment: Manifestation in daily activities and decisions (By 2021; Jasinenko and Steuber 2023). | 1. Authenticity: Genuine reflection of organizational values (Jasinenko and Steuber 2023; Walker and Reichard 2020). 2. Magnitude: Global scope and potential (Almandoz 2023; Dimitrov 2022). 3. Significance: Impact on internal and external stakeholders (Handa 2023; Ingen et al. 2021; Martela and Pessi 2018). 4. Aspiration: Ambition for significant future objectives (Crane 2022; Ingen et al. 2021; Tan and Antonio 2022). 5. Direction/Guidance: Providing a path or route (Ingen et al. 2021; Tuin et al. 2020). 6. Unification: Connecting individuals around a shared purpose (Almandoz 2023; Ingen et al. 2021). 7. Transformative: Capacity to bring change or innovation (Dimitrov 2022; Hurth and Stewart 2022). 8. Inspiration: Energizing actions and behaviors (Ingen et al. 2021; Islam et al. 2023; Jasinenko and Steuber 2023). |

| Dimensions/Perspectives | Internal: Individuals’ intrinsic motivations (Crane 2022; Knippenberg 2020). External: Impact on the external context (By 2021; Gavarkovs et al. 2023; Handa 2023; Jasinenko and Steuber 2023). | Inside-Out: Intrinsic motivations and values that drive an organization (Ocasio et al. 2023; Rindova and Martins 2023). Outside-In: External demands, societal needs, environmental considerations (Almandoz 2023; Ocasio et al. 2023; Rindova and Martins 2023). |

| Expression | Found in everyday actions, decisions, and goals (By 2021; Jasinenko and Steuber 2023). | Embodied in the organization’s identity, activities, and stakeholder interactions (Fitzsimmons et al. 2022; Hong et al. 2021). |

| Mediator | Outcomes | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Stakeholder trust and legitimacy | License to operate | Crane (2022), Enslin et al. (2023), and Kaplan (2023) |

| Stakeholders’ wellbeing | ||

| Organizational reputation | ||

| Employee organizational trust | ||

| Organizational performance | ||

| Employee performance | Organizational performance | Gwartz and Spence (2020), Ponting (2020), Roberts (2020), Tan and Antonio (2022) |

| Financial value | ||

| Work effectiveness | ||

| Wellbeing | Employee performance | Hurth and Stewart (2022), Ponting (2020), Trachik et al. (2020), and Trachik et al. (2022) |

| Fulfillment of human needs | ||

| Mitigate the risk of suicide | ||

| Work engagement | ||

| Meaning/Significance | Self-realization | Almandoz (2023), Gavarkovs et al. (2023), Handa (2023), Jasinenko and Steuber (2023), Kempster et al. (2019), and Kempster and Jackson (2021) |

| Fulfillment of human needs | ||

| Shared identity | ||

| Organizational cohesion | ||

| Shared identity | Organizational cohesion | Cavazotte et al. (2020), Crane (2022), Kaplan (2023), Knippenberg (2020), and Ponting (2020) |

| Sense of oneness | ||

| Employee organizational trust | ||

| Job satisfaction | Employee performance | Gavarkovs et al. (2023), Jasinenko and Steuber (2023), Martela and Pessi (2018), Ponting (2020), Rey and Bastons (2018) |

| Work engagement | ||

| Employee organizational trust | ||

| Employee turnover reducing | ||

| Motivation | Job satisfaction | Kaplan (2023), Meynhardt et al. (2023), Tuin et al. (2020), and Walker and Reichard (2020) |

| Work engagement | ||

| Employee performance | ||

| Guidance/Direction | Organizational commitment | By (2021), Ingen et al. (2021), Islam et al. (2023), Peeters et al. (2023), and Rindova and Martins (2023) |

| Alignment to change management | ||

| Organizational learning | ||

| Work effectiveness | ||

| Organizational commitment | Employee performance | Bhattacharya et al. (2023), Brendel et al. (2023), Islam et al. (2023), Qin et al. (2022), and Tan and Antonio (2022) |

| Work engagement | ||

| Organizational performance | ||

| Alignment to change management | ||

| Employee turnover reducing | ||

| Trust | Organizational cohesion | Bunderson and Thakor (2022), Lawson and Weberg (2023), and Qin et al. (2022) |

| Stakeholder trust and legitimacy | ||

| Employee organizational trust | ||

| Sense of oneness | Shared identity | Brendel et al. (2023), Cavazotte et al. (2020), Trachik et al. (2020), and Trachik et al. (2022) |

| Meaning | ||

| Trust | ||

| Organizational cohesion | ||

| Mitigate the risk of suicide | ||

| Self-realization | Self-efficacy | Martela and Pessi (2018), and Tuin et al. (2020) |

| Meaning | ||

| Significance | ||

| Resilience | ||

| Self-efficacy | Self-realization | Brown et al. (2021), Handa (2023), Martela and Pessi (2018), and Nakamura et al. (2022) |

| Adaptability/Agility | ||

| Resilience | ||

| Work effectiveness | ||

| Employee performance | ||

| Adaptability/Agility | Organizational performance | Dimitrov (2022), Gavarkovs et al. (2023), Lawson and Weberg (2023), and Tan and Antonio (2022) |

| Resilience | ||

| Competitive advantage | ||

| Alignment to change management | ||

| Resilience | Self-realization | Crane (2022), Handa (2023), Kaplan (2023), Trachik et al. (2020), and Trachik et al. (2022) |

| Adaptability/Agility | ||

| Organizational performance | ||

| Creativity/Innovation | Work engagement | Kaplan (2023), Meynhardt et al. (2023), Ocasio et al. (2023), and Rindova and Martins (2023) |

| Organizational learning | ||

| Organizational performance | ||

| Work engagement | Employee performance | Cavazotte et al. (2020), Jasinenko and Steuber (2023), Nazir et al. (2021), Tan and Antonio (2022), and Tuin et al. (2020) |

| Job satisfaction | ||

| Motivation | ||

| Work effectiveness | Employee performance | Knippenberg (2020), Peeters et al. (2023), and Tan and Antonio (2022) |

| Financial value | ||

| Organizational performance | ||

| Employee organizational trust | Organizational commitment | Bunderson and Thakor (2022), and Qin et al. (2022) |

| Stakeholder trust and legitimacy | ||

| Shared identity | ||

| Employee turnover reducing | ||

| Alignment to change management | Organizational learning | Brendel et al. (2023), Dimitrov (2022), Losada-Vazquez (2022), Ponting (2020), and Qin et al. (2022) |

| Organizational commitment | ||

| Adaptability/Agility | ||

| Organizational performance | ||

| Organizational learning | Creativity/Innovation | Crane (2022), Losada-Vazquez (2022), and Peeters et al. (2023) |

| Organizational performance | ||

| Alignment to change management | ||

| Organizational culture | ||

| Positive effects on individuals outside the organization | Stakeholders’ wellbeing | Ingen et al. (2021) |

| Organizational reputation | ||

| Employer attractiveness | ||

| Organizational culture | Organizational learning | Bunderson and Thakor (2022); Dimitrov (2022), Gwartz and Spence (2020), Hong et al. (2021), and Losada-Vazquez (2022) |

| Employer attractiveness | ||

| Organizational performance | ||

| Employee organizational trust | ||

| Marketing | Employer attractiveness | Enslin et al. (2023), Fitzsimmons et al. (2022), and Ponting (2020) |

| Organizational reputation | ||

| Financial value | ||

| Organizational reputation | Stakeholder trust and legitimacy | Almandoz (2023), Hong et al. (2021), Jasinenko and Steuber (2023), and Qin et al. (2022) |

| License to operate | ||

| Marketing | ||

| Employer attractiveness | ||

| Competitive advantage | Financial value | Dimitrov (2022), Enslin et al. (2023), Fitzsimmons et al. (2022), Kaplan (2023), and Ocasio et al. (2023) |

| Organizational performance | ||

| Creativity/Innovation | ||

| Organizational cohesion | Sense of oneness | Almandoz (2023), Bronk et al. (2023), Trachik et al. (2020), and Trachik et al. (2022) |

| Significance |

| Moderator | Outcomes | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Perception of impact | Meaning | Ingen et al. (2021) |

| Motivation | ||

| Job satisfaction | ||

| Resilience | ||

| Employee performance | ||

| Employer attractiveness | ||

| Autonomy | Wellbeing | Bhattacharya et al. (2023), Crane (2022), Gavarkovs et al. (2023), Ingen et al. (2021), Jack et al. (2022), Martela and Pessi (2018), Nazir et al. (2021), and Walker and Reichard (2020) |

| Motivation | ||

| Sense of oneness | ||

| Creativity/Innovation | ||

| Authenticity | Meaning | Crane (2022), Ingen et al. (2021), Kempster et al. (2019), and Martela and Pessi (2018) |

| Trust | ||

| Motivation | ||

| Balance (Work-life balance) | Employee performance | Ingen et al. (2021), Nazir et al. (2021), and Ponting (2020) |

| Meaning/Significance | ||

| Work engagement | ||

| Positive effects on individuals outside the organization | ||

| Communication | Organizational performance | Bhattacharya et al. (2023), Ingen et al. (2021), Knippenberg (2020), and Qin et al. (2022) |

| Shared identity | ||

| Organizational commitment | ||

| Adaptability/agility | ||

| Work effectiveness | ||

| Organizational culture | ||

| Organizational cohesion |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ribeiro, M.F.; Costa, C.G.d.; Ramos, F.R. Exploring Purpose-Driven Leadership: Theoretical Foundations, Mechanisms, and Impacts in Organizational Context. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14070148

Ribeiro MF, Costa CGd, Ramos FR. Exploring Purpose-Driven Leadership: Theoretical Foundations, Mechanisms, and Impacts in Organizational Context. Administrative Sciences. 2024; 14(7):148. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14070148

Chicago/Turabian StyleRibeiro, Marco Ferreira, Carla Gomes da Costa, and Filipe R. Ramos. 2024. "Exploring Purpose-Driven Leadership: Theoretical Foundations, Mechanisms, and Impacts in Organizational Context" Administrative Sciences 14, no. 7: 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14070148

APA StyleRibeiro, M. F., Costa, C. G. d., & Ramos, F. R. (2024). Exploring Purpose-Driven Leadership: Theoretical Foundations, Mechanisms, and Impacts in Organizational Context. Administrative Sciences, 14(7), 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14070148