Abstract

Collaboration in interorganizational networks requires specific governance choices to align participants with collective goals. However, these choices often fail to mitigate conflicts and may catalyze tensions that lead to disaffiliation. This study investigates four critical tensions identified in existing literature: (1) efficiency versus inclusion in decision-making; (2) flexibility versus stability; (3) internal versus external legitimacy; and (4) unity versus diversity. Through a case study of a credit union that disaffiliated from a cooperative network, we explore how these tensions manifest and their repercussions on both the network’s functionality and the behavior of its members. Our findings reveal that such governance tensions can be harmful both to the network and to the participating organizations. Tensions between unity and diversity, stability and flexibility, and external and internal legitimacy can compromise the effectiveness of the network and even hinder participating organizations in conducting their business. In extreme situations, these tensions contribute to the strategic decision to disaffiliate. This research extends theoretical understanding by delineating the specific impact of governance tensions on exit decisions within interorganizational networks.

1. Introduction

In the current context of rapid economic change and environmental uncertainty, organizations are increasingly recognizing the challenges of achieving their objectives independently (van den Oord et al. 2023). The evolving market demands arising from competitive pressures underscore the deficiencies of individual companies acting alone, necessitating other means of acquiring essential resources (Dagnino et al. 2015). To overcome these challenges, organizations often engage in external collaboration (Vahlne and Johanson 2021; De Pourcq and Verleye 2022), forming interorganizational networks (i.e., Wegner et al. 2011; Vahlne and Johanson 2021; De Pourcq and Verleye 2022) to share resources and collectively pursue common goals (Camarinha-Matos and Molina 2010).

Since interorganizational networks promise countless benefits, past research offers multiple explanations of network drivers, including partner geographical location, industry traits, the charisma of key decision-makers, and firm-level uncertainties, among others (Novoselova 2022). Much of the existing literature focuses on why connections exist between organizations while often neglecting to explain why they dissolve. This oversight fails to recognize the inherent fragility of networks, which are prone to disintegration as they evolve experiencing the termination or replacement of relationships (Harini and Thomas 2021). The vulnerability arises from the networks’ non-hierarchical structure, lack of a single governing authority, and temporal asynchronies among members, frequently leading to relationship tensions (Jarvenpaa and Välikangas 2022). These tensions have been well documented in the literature for some time (i.e., Provan and Kenis 2008; Roth et al. 2012; Schmidt et al. 2019; Fortes et al. 2023), and are known to emerge from the competing demands of network governance. Tensions related to network governance manifest in four ways, namely (1) efficiency versus inclusion in decision-making; (2) flexibility versus stability; (3) internal versus external legitimacy; and (4) unity versus diversity (Provan and Kenis 2008; Saz-Carranza and Ospina 2011). Governance tensions are pivotal in explaining why organizations might choose to disaffiliate from interorganizational networks. However, this phenomenon remains poorly understood, particularly in the context of cooperativism.

This study focuses on the Brazilian National Cooperative Credit System (henceforth NCCS), a three-tiered network of credit cooperativism governed by a distinct entity established in accordance with the Network Administration Organization (NAO) governance mode. The first tier comprises single credit unions. The second tier is constituted of cooperative centers and interorganizational networks formed by single credit unions. The third tier consists of confederations, which are also interorganizational networks formed by cooperative centers with self-focused activities (Brasil 1971, 2022). Despite the cohesive structure of the NCCS, which is currently made up of 818 single credit unions, 221 credit unions notably remain independent from the 34 cooperative centers that comprise the system. Single credit unions are independent organizations that are not currently affiliated with any second- or third-tier interorganizational network. Many have previously been members of a cooperative center (Camelo et al. 2021), suggesting potential issues with governance.

This paper examines the critical case of a credit union that opted to leave the cooperative center. It addresses the following research question: How do governance tensions impact collaboration in cooperative centers, prompting credit unions to disaffiliate from the interorganizational networks to which they belong? The study aims to empirically identify the governance tensions that precipitated this departure, providing valuable insights into the dynamics that may compel organizations to exit an interorganizational network. Our study thus responds to the call identified by van den Oord et al. (2023), which notes that more evidence is needed to understand the variations in outcomes across different network governance modes. Our results contribute to organizational theory by delineating the impact of paradoxical governance tensions on disaffiliation from interorganizational networks. Furthermore, they contribute to practice by helping network managers mitigate tensions inherent to governance and thereby learn how to sustain collaboration.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Interorganizational Networks

Organizations invariably operate within networks, regardless of their market, size, or configuration. Even small organizations, in which decision-making is highly centralized, manage a range of external relationships, implying some level of network involvement (Shipilov 2012). Nevertheless, interorganizational networks represent a more distinctly defined phenomenon. Herein, an interorganizational network is defined as an arrangement involving three or more autonomous organizations that coordinate their actions to achieve collective objectives while maintaining their independence (Roth et al. 2012). Networks thus consist of individual connections formed among organizations that maintain multiple, simultaneous relationships with various actors at any given moment (Harini and Thomas 2021). Within an interorganizational network, each participant organization contributes unique individual resources, thereby enhancing overall outcomes through synergy (Dagnino et al. 2015). This interconnection of diverse but complementary resources is crucial, as interdependence is one of the most prominent drivers in forming interorganizational arrangements. It allows organizations to manage and leverage their interdependencies effectively (Gulati and Gargiulo 1999).

Nooteboom et al. (1997) highlighted that, to derive the full benefits of networking, organizations must seek partners with whom they can (1) share the costs and risks of the intended collaboration, (2) enhance their resources/competencies, (3) access complementary skills, and (4) increase competitiveness. The propensity of organizations to engage with others sharing similar origins or domains (e.g., individual and organizational goals)—known as homophily—serves not only as a motivator for creating or joining an interorganizational network but also simplifies the collaboration processes (Provan and Kenis 2008). Despite the efforts to conduct joint activities and potentially achieve shared benefits, organizations that operate in an interorganizational network remain free to fulfill individual strategic objectives unilaterally (Wegner et al. 2011; Roth et al. 2012). As a result, networks often cannot fulfill ambitions of collective benefits because of the heterogeneous expectations and strategic agendas of the participants, including differences in time horizons of short- versus long-term goals (Jarvenpaa and Välikangas 2022).

2.2. The Governance of Interorganizational Networks

When organizations engage in networks, they often compromise individual freedoms in favor of collective interests. This compromise generally only extends insofar as participants’ individual interests can coexist with those of the network. Network governance concerns the structures and processes used by organizations to direct, coordinate, allocate resources, and oversee activities across a network to facilitate collective action and accountability (van den Oord et al. 2023). Given the interdependence required to achieve common objectives, the multiple relationships, and the complexity of operations, networks exemplify a typological definition of governance (Wang and Ran 2022).

Stoker (1998) points out several basic premises underpinning the concept of network governance: (1) organizations do not exist in isolation; they must interact and integrate with others, contributing to collective actions; (2) organizations exchange resources to survive and achieve their objectives, whether these are pursued individually or jointly, thereby creating interdependencies; and (3) the dynamics of interaction and the established rules of the game within the network are crucial for obtaining results.

Network governance entails both structural and instrumental dimensions. The structural dimension concerns the governance framework and is divided into three elements: centralization, characterized by the hierarchical structure in place; specialization, which dictates control over network actors and limits their actions; and formalization, characterized by formally established rules, norms, and forums. The instrumental dimension involves the practical application of the structural framework. It comprises the coordination mechanisms, incentive systems (tangible or intangible) to shape behavior towards meeting network goals, and the monitoring and evaluation of both the network outcomes and the participant behavior (Roth et al. 2012).

Three ideal types of governance modes are employed by interorganizational networks: (1) self-governed network or shared-participant mode; (2) lead organization mode; and (3) network administrative organization (NAO) mode. Self-governed networks comprise a simplified and decentralized governance mode in which all network members jointly participate in decision-making. This mode requires high commitment and effort from its participants and is typically suitable for emerging networks with few participants and low formalization (Provan and Kenis 2008). In the lead organization governance mode, one member takes on leadership and is responsible for governance (Provan and Kenis 2008). This is a common mode in supply chain networks, such as car manufacturers and their suppliers. In the network administrative organization (NAO) mode, a separate entity is created to coordinate the network’s activities and reduce opportunistic behavior (Nooteboom et al. 1997). The NAO acts as the network’s managerial hub, potentially with its own staff, executive body, and offices, and is responsible for maintaining network cohesion and managing complexities associated with shared governance (Roth et al. 2012; Provan and Kenis 2008). Strategic decisions are made by the board, while operational decisions are made by the NAO’s managers (Saz-Carranza et al. 2016). According to a recent review by van den Oord et al. (2023), the NAO is the most frequently examined mode in empirical studies. This is likely because power is concentrated in the administrative entity, making it more susceptible to experiencing tensions that could reduce network effectiveness.

2.3. Tensions in the Governance of Interorganizational Networks

The concept of tension within the literature on interorganizational networks is multifaceted. Tensions are sometimes interpreted as paradoxes, as negative consequences arising from these paradoxes, or as conflicting relationships between two or more elements (Fortes et al. 2023). Traditionally viewed through a negative lens, these tensions can also strengthen partnerships, enhance resource sharing, build trust, and improve regulatory frameworks when addressed creatively (Lee 2022). The governance of interorganizational networks is marked by at least four fundamental tensions or paradoxes: (1) efficiency versus inclusion; (2) flexibility versus stability; (3) internal versus external legitimacy; and (4) unity versus diversity (Provan and Kenis 2008; Saz-Carranza and Ospina 2011; Schmidt et al. 2019).

Inclusive and collective decision-making, which incorporates a broad range of participants, tends to enhance the effectiveness of NAOs by introducing diverse perspectives and fostering horizontal relations. The multiplicity of actors leads to more viewpoints, interpretive tendencies, and opinions, which turns decision-making into a more democratic and creative process (Schmidt et al. 2019). However, the complexity of governance escalates with the number of participants, complicating decision-making processes and necessitating significant resource allocation. This introduces a tension between the efficiency of decision-making and the breadth of participation (Provan and Kenis 2008). Research in the retail construction material industry by Schmidt et al. (2019) highlights two critical contingent challenges in balancing participative inclusivity with decision-making efficiency: trust in network management and the geographic dispersion of members. Unlike previous studies that predominantly focus on trust among participants in interorganizational relations, this study finds that trust in management enhances decision-making efficiency by reducing the need for extensive inclusion. Conversely, geographic dispersion hinders inclusion by creating barriers to member interaction in the decision-making process.

The dichotomy between network flexibility and stability presents another tension. Stability, essential for long-term sustainability and for ensuring legitimacy, is marked by well-structured processes and promotes trust, knowledge sharing, and interdependence (Provan and Kenis 2008). Conversely, flexibility allows networks to quickly respond to emerging demands. The adaptability of interorganizational networks and their potential for rapid collective articulation are important attributes for responding to challenges promptly. The conflict lies in the fact that, to guarantee stability, it is necessary to formalize decision-making processes that strengthen governance, which can in itself stifle flexibility—which is precisely the key advantage of networks over hierarchies (Provan and Kenis 2008).

For interorganizational networks to thrive, they must maintain internal legitimacy such that members see their interests and objectives reflected in the network’s actions. It turns out that interorganizational networks, regardless of the mode of governance adopted, also need to guarantee competency at the network level so that internal and external expectations are met, creating external legitimacy (Provan and Kenis 2008). Tensions between internal and external legitimacy occur precisely when there is a perception of imbalances in the allocation of efforts and resources (Provan and Kenis 2008). Investigating an interorganizational network composed of partners in the supply chain of a North American car factory, Kim and Choi (2021) identify that high integration and collaboration between participating organizations positively impact the internal legitimacy of the network. In contrast, the authors find that aspects of the structural dimension, such as coordination and control, negatively impact external legitimacy. In the context of the healthcare industry, Romiti et al. (2020) state that NAO structures tend to accommodate both internal and external legitimacies better, reducing the potential for this tension to manifest.

Lastly, the tension between unity versus diversity within networks is critical. While unity through integration strengthens the network (Saz-Carranza and Ospina 2011) via consensus on objectives, diversity is essential for the development of new resources. Diversity comprises the different resources and organizational and cultural characteristics of network members, in addition to individual forms of action and organizational processes that, when combined, can result in synergistic gains in new resources (Saz-Carranza and Ospina 2011). It is important to highlight that NAOs are developed to promote and guarantee unity (Provan and Kenis 2008; Saz-Carranza and Ospina 2011). Consensus of goals is a critical success factor in governance, since members operating in interorganizational networks in which network-level objectives are aligned experience greater engagement (Schmidt et al. 2019). At the same time, as the search for unity is highly relevant to the sustainability and efficiency of the network, diversity plays a fundamental role in developing skills and leveraging synergy (Saz-Carranza and Ospina 2011). The tension between unity and diversity occurs when striving for unity inhibits plurality and the convergence of diverse elements at the network level.

The four tensions presented can be revealed through discomfort or conflict between participants, according to their priorities and individual interests. They also influence the decision of a network member to leave or remain. Interestingly, Lee’s (2022) study reveals how network tensions pertaining to accountability can be viewed as opportunities as well, emphasizing that the strategic management of these tensions enhances the mission and the accountability of the entire network.

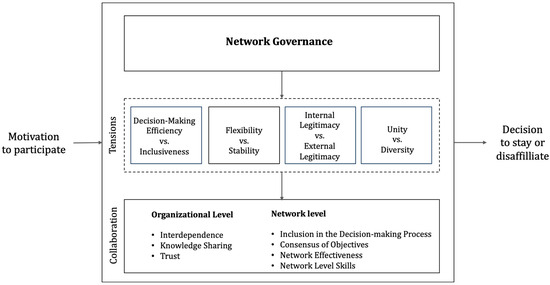

Figure 1 displays the tensions that emerge in network governance and their impact on the network and organizational levels, which leads to the decision of network members to stay or disaffiliate. This study empirically explores how governance tensions affect network cohesion and continuous collaboration.

Figure 1.

Research framework. Source: The authors.

3. Method

The empirical context defined in this study refers to interorganizational networks that face the evasion of members. Specifically, we analyze the withdrawal of a credit union from a cooperative center (NAO) to which it was affiliated. Participation in such a cooperative center, which aggregates several credit unions, is encouraged by the Central Bank of Brazil. This body regulates and supervises the financial institutions under the NCCS in the country (Central Bank of Brazil 2022). Our research aims to explain how governance tensions within cooperative centers can lead to single credit unions opting to leave. To achieve this, we adopt a case study approach. This method is recommended when the phenomenon under study is a contemporary issue and the researchers have the opportunity to access contextual data with the intention of exploring how and why changes happened (Yin 2009). The case study method is also prevalent in existing literature examining governance tensions within interorganizational networks (Fortes et al. 2023). Thus, the unit of analysis in our study is at the network level. Our focus lies on the governance of an interorganizational network operating in the NAO mode (i.e., cooperative center) and on how emerging governance tensions impact the decisions of network members (i.e., single credit unions) to disaffiliate.

3.1. Case Selection

The NCCS in Brazil comprises 818 single credit unions. Among them, 597 are affiliated with one of the 34 cooperative centers, leaving 221 credit unions independent and not affiliated with any cooperative center (Central Bank of Brazil 2022). In August 2021, Mundo Coop magazine presented the results of a research study entitled “Systemic Integration of Independent Credit Unions: Expectations and Challenges” (Camelo et al. 2021). The results stem from a field study on independent credit unions, which included the participation of 58 (26%) of the 221 unaffiliated credit unions at that time. When asked about their history of participation in a cooperative center, 31 reported having joined a cooperative center that they later left (Camelo et al. 2021).

Our case selection criteria are as follows: (1) cooperative centers that had experienced the disaffiliation of credit unions; (2) instances of disaffiliation that occurred within the last 12 months; (3) willingness of both the cooperative center and the credit union to participate in the study. By following this criteria, we identified a case for empirical research, which we describe below.

The cooperative center subject of this study is named “IntegraCoop”1. Operating nationally, it comprises 11 credit unions whose assets exceed 1.35 billion US dollars. It offers a variety of business support solutions to participants, such as core banking systems, billing, payments and receipts, financial centralization, payroll services, and risk and compliance management. The services offered by IntegraCoop support its members in attending to more than seventy thousand customers. The credit union in this study, known as “Aurora Union”, operates in the southern region of Brazil. It serves over seven thousand customers and manages assets totaling more than 13.5 million US dollars. Aurora Union offers a range of services including funding investment options, credit, and pension plans, as well as benefits in health, education, and consumption that are subsidized through partnerships with other organizations. Its tenure in IntegraCoop lasted approximately two and a half years, from 2018 to early 2022, when it opted for disaffiliation.

3.2. Data Collection

Semi-structured interviews were carried out based on interview protocols specifically developed for this research. The interview protocol (available upon request) comprised straightforward, objective questions for all participants that facilitated conversational interviews, allowing interviewees to expand on their responses within the guided framework of the inquiries (Stake 2016). The questions focused on the reasons behind the decision to disaffiliate; however, throughout the interviews, participants were free to address issues beyond the questions posed.

Two interview protocols were developed, tailored respectively to the informants from the credit union, Aurora, and the cooperative center, IntegraCoop. The interview protocol regarding Aurora Union was validated in July 2022 through its application to a similar disaffiliation scenario that occurred in 2018. Validation involved two individuals engaged in a separate disaffiliation process. Afterwards, a few adjustments were implemented to refine questions and more accurately probe the constructs under study.

Ten interviews were carried out with informants of the two organizations—five from Aurora Union and five from IntegraCoop. For Aurora, the interviewees include one board member, three executive board representatives (one of whom had left the organization but was authorized to participate), and one senior manager, all of whom are actively involved in decision-making processes related to affiliation and disaffiliation, as well as daily governance activities. For IntegraCoop, the interview subjects were three executive board members who handle governance-related tasks, one superintendent, and one senior manager who works directly with representatives of the affiliated credit unions. All interviews were recorded via videoconferencing tools (e.g., Microsoft Teams) and transcribed for analysis.

Table 1 categorizes the interviewees as follows: (1) ‘CO’ prefix for interviews conducted within Aurora Union; (2) ‘CE’ prefix for interviews conducted within IntegraCoop; (3) numbering from 01 to 05, in chronological order. Pseudonyms were assigned to participants to improve the paper’s readability.

Table 1.

Categorization of interviewees.

Prior to conducting interviews, a comprehensive review of 13 documents was undertaken to enhance the understanding of the events under investigation (available upon request). For Aurora Union, we accessed and analyzed documents related to the affiliation and disaffiliation processes. These included meeting notes and materials presented at those meetings, as well as a management adequacy plan that was submitted and approved by the Central Bank of Brazil following the disaffiliation. Additionally, we reviewed the credit union’s bylaws, financial statements, and management reports from before, during, and after its involvement with the cooperative center. Regarding IntegraCoop, our analysis included the organizational chart, management reports, and balance sheets covering the period before, during, and after Aurora Union’s participation. We also examined the internal regulations of IntegraCoop’s formally constituted committees and its bylaws.

3.3. Coding and Data Analysis

The analysis of the responses was methodically structured into two coding rounds using a deductive approach, focusing on governance issues. The first coding round concentrated on network governance, where the categories comprised the structural (coordination, incentives, and control) and instrumental (centralization, formalization, and specialization) dimensions. Additionally, this round examined collaboration, categorizing responses into individual (interdependence, knowledge sharing, and trust) and collective aspects (decision-making process inclusion, consensus of objectives, network effectiveness, network efficiency, and network-level competencies).

After that, the second round specifically addressed tensions in the context of network governance. This alignment supports the study’s goal to explain how governance tensions in the context of cooperative centers may lead to disaffiliation. Responses were, therefore, coded based on their potential link to the disaffiliation decision.

Table 2 presents a summary of the coding schema used in the analysis.

Table 2.

Coding of constructs.

4. Findings

4.1. Context

Organizations may join networks for various reasons. A cooperative center, for example, provides a range of services to its participants, including payroll management, financial centralization, current accounts, marketing, internal controls, and auxiliary supervision—namely conducting audits required by regulatory bodies. Specifically, Aurora Union’s decision to join IntegraCoop was driven by the desire for scale and agility. By transferring several operational processes to the cooperative center, the credit union could expand the product portfolio offered to its customers. This indicates a clear alignment between the services provided by IntegraCoop and the expectations of Aurora Union. Additionally, the findings reveal that incentives from the industry’s main regulatory body, the Central Bank of Brazil, played a significant role in encouraging single credit unions to affiliate with cooperative centers.

4.2. Governance Tensions at IntegraCoop

4.2.1. Efficiency versus Inclusiveness

The governance structures of cooperative centers are legally mandated and organized hierarchically. As evidenced by the reviewed documents of our studied case, the board of directors—a key administrative body outlined in the bylaws—includes a representative from each member’s credit union, ensuring broad inclusion and representation in decision-making. As explained by a top manager from IntegraCoop: “Our board of directors is made up of representatives from each single organization, okay? Everyone is on the board. There’s a representative from each credit union with a seat on the board” (Rafael).

IntegraCoop operates within the instrumental dimension to promote the greatest possible inclusion within its governance, mainly through formalization and centralization. It uses formally established forums, such as risk and compliance committees and business committees, which consist of top managers from single credit unions. These committees discuss various topics before the board of directors’ meetings. Executive directors from single credit unions are convened to discuss these topics, aiming to consolidate arguments or even make preliminary decisions on certain issues. Although these forums have a technical focus, they play a crucial role in shaping strategic decisions.

According to the evidence collected, the expectation is that deliberations at the board level are to be replicated within the internal environments of credit unions. This enables representatives who serve as board members at IntegraCoop to engage in more objective deliberations during meetings. Interviewees highlight that this approach aims to maximize inclusion in the decision-making process and encourage active participation. However, the adopted governance structure is complex and requires extensive resource allocation, including the involvement of top managers from all affiliated credit unions, which compromises the efficiency of the decision-making process.

Furthermore, decisions that are not strategically significant, and thus do not necessitate high-level intervention, are still escalated to the upper echelons of IntegraCoop, further straining resources. Representatives from both IntegraCoop and Aurora Union have expressed that, despite substantial efforts and resource allocation across various levels, the outcomes are often unsatisfactory. This sentiment is captured by Mariana, who noted,

“[The decision-making process] does not have a rational flow. It is a construction that you try to support, going up the forums, even going up the ladder, but sometimes, it can reach the top regarding technical matters and be destroyed in terms of politics. So, there is no rationality.”

Despite these challenges, the well-established forum structures are perceived as positive, as put forward by one of the representatives from Aurora Union:

“(…) there was this group of directors who (…) met at face-to-face meetings, systematically, where all the executives were present. There was this exchange. They also promoted monthly agendas for the financial managers. The Compliance committee’s agenda, where they brought this enhancement to meet such demand, or guidance on some process. Anyway, these forums were good, they helped with knowledge.”(Sofia)

Generally, the tension between the efficiency of the decision-making process and the inclusion of participants manifests when the latter requires an excessive allocation of resources, which impacts the network’s ability to make decisions efficiently. In the case under study, the high degree of inclusion of credit union representatives is supported by various forums and meetings, which necessitate significant resources to manage. Although these efforts are intended to enhance interaction among participants and accelerate the decision-making process, the final outcomes do not always mirror these intentions. This scenario is characterized by a fundamental tension between decision-making efficiency and participant inclusion, with a clear prioritization of inclusion at the expense of efficiency. However, since Aurora appreciated inclusion, this tension alone did not prompt the withdrawal from IntegraCoop.

4.2.2. Flexibility versus Stability

The trade-off between flexibility and stability within IntegraCoop was evident through the responses about the network’s responsiveness to challenges. Representatives express concerns that the existing governance structure compromised flexibility. As one executive from the cooperative center explains: “Here we see a very strong implementation at the three levels, and this has positive issues and negative issues, right? In a way, it somewhat hampers decisions” (Isabella).

The most striking evidence of the trade-off focused on the decision-making process. When asked about the network’s ability to adapt quickly in unusual situations, the answers reveal a lack of flexibility. The governance protocol mandates strict adherence to established procedures, even in urgent situations. This is encapsulated by the requirement to convene extraordinary meetings of the board of directors for certain decisions, as detailed in the following excerpt:

“You must follow the rite [protocol]. Sometimes, you can even arrange an extraordinary meeting, but you must follow the procedure for some things. You cannot decide without going through the appropriate forums. Executives must pass some decisions; some decisions need to be passed by the board of directors; you cannot escape that”.(Mariana)

Interviewees from Aurora Union underscore how IntegraCoop’s operational and management processes not only created communication barriers across different levels but also slowed down the response time to emerging issues, diminishing the network’s overall effectiveness. The difficulty in adapting to the varied needs of the various credit unions also suggests that the emphasis on stability stifled IntegraCoop’s flexibility. Aurora Union respondents report numerous challenges faced in addressing their unique requirements, contributing to a negative perception of the network’s effectiveness. The difficulty in addressing the particularities of Aurora Union was negatively impacted by the stability-oriented approach adopted by IntegraCoop, as reported by one of the executives from Aurora Union:

“Due to our need to adjust processes, we here sought the headquarters with an agenda for our needs, when possible, right? And there wasn’t this space of ten to fifteen minutes, a window: let’s talk about how the operation is going. That never happened”.(Ana)

Overall, the collected evidence suggests that the emphasis on maintaining stability in governance and operations directly restricts IntegraCoop’s ability to be flexible. This rigidity in adapting to new circumstances underscores a fundamental tension between stability and flexibility within the network. Ultimately, the persistent inability of IntegraCoop to accommodate the unique and evolving needs of Aurora Union, exacerbated by a stability-focused governance structure that restricts flexibility, was a decisive factor in Aurora Union’s decision to disaffiliate from the network.

4.2.3. Internal Legitimacy versus External Legitimacy

Evidence points to difficulties pertaining to the network’s internal legitimacy. Despite the availability of resources and support from IntegraCoorp, some participants, such as Aurora Union, sought assistance from other credit unions, which were perceived to be more adept in certain matters. A top manager from the cooperative center voices this issue:

“Credit unions one and two have representatives who talk more and express themselves better than others. And, consequently, when another credit union wants to exchange an idea on a certain matter, it often does not look for IntegraCoop. It contacts that credit union directly that stood out in that committee talking about that matter”.(Rafael)

The interviewees from Aurora Union feel that existing asymmetries negatively impacted their ability to align their distinct needs with collaborative attributes at the network level. This was particularly evident in how the apportionment of IntegraCoorp’s expenses did not align with Aurora Union’s financial capacity, adding to the internal legitimacy issues. Moreover, Aurora Union’s employees highlight discomfort arising from differences, especially when it comes to directing efforts to meet the credit union’s specific needs. This perception was not exclusive to representatives of the Aurora Union. According to the reviewed reports on the performance of individual credit unions within the network, IntegraCoop representatives explicitly acknowledged the difficulties faced by Aurora Union in acquiring competencies at the network level.

In addition, operational and management processes within IntegraCoop created communication barriers, hindering timely responses to emerging situations and affecting the network’s overall effectiveness. Aurora Union respondents report difficulties adapting to the asymmetrical nature of IntegraCoop, which they believe detracts from the network’s effectiveness.

The perceptions of internal legitimacy and interdependence were further complicated by the network’s difficulty in developing new resources. An account from one of the respondents shows that, in some situations, the services offered by IntegraCoop to its affiliates did not meet expectations. Furthermore, there was no feeling of security regarding the equal provision of these services. An executive board member at Aurora Union shares his frustration:

“I asked about a demand from the Central Bank, and the person at IntegraCoop replied: I do not know; I did not even know that this existed; it is the central department that does it. However, the central department is not doing it. And then I was disappointed, you know? Because I thought: damn, who can guarantee that they are not doing it for their credit unions? So, I started to realize that there are two standards, right?”(Lucas)

The performance was contrary to expectations, underscoring the deficiencies in IntegraCoop’s internal legitimacy. The services provided failed to achieve the anticipated results for the individual credit unions. This shortfall had significant repercussions; members began to disengage from IntegraCoop due to the unsatisfactory service delivery. As Mariana from the cooperative center reports, “We were unable to activate our members. Our members stopped doing business with us because they could not access the channels due to technology difficulties. Some left.” The decline in membership of individual credit unions was corroborated by the documents reviewed.

When directly questioned about the reasons for disaffiliation, additional insights concerning internal legitimacy were uncovered. Nearly all representatives from Aurora Union cite the high costs and lack of perceived benefits from their participation in IntegraCoop as critical factors in their decision. These concerns about costs, combined with not achieving anticipated results, significantly hastened Aurora Union’s exit process.

Regarding external legitimacy, continuous efforts were evident to ensure its maintenance. Strengthening IntegraCoop remained a priority, with intensive work directed toward achieving significant outcomes at the network level, as highlighted by one of the IntegraCoop executives during the interview: “The work is hard for the cooperative center, okay? Mainly in terms of promoting the business, right? IntegraCoop must grow; it has to go there and run a campaign and do something, right? Raise resources and grant credit, in short” (Rafael).

When dealing with the impacts of disaffiliation, concerns about external legitimacy also emerge in the interviews. Representatives from Aurora Union observe that the focus on maintaining external legitimacy often came at the expense of internal legitimacy. This shift in focus resulted in the neglect of individual needs, as highlighted by an executive director of the credit union: “They [IntegraCoop] do not want to know [about our context]. They only arrive with the number: you have to increase the number of customers, you have to increase this and that. But they are not so worried about the difficulties we are having here.” (Ana).

Based on the findings, there was a clear deficiency in internal legitimacy. Interviews highlight that Aurora Union, among others, did not have its unique needs met, which was further corroborated by documents showing that these needs were sometimes addressed through resources from other credit unions not affiliated with IntegraCoop. Meanwhile, efforts to ensure external legitimacy were relentless and effective, as demonstrated in the annual reports. The annual reports detailed IntegraCoop’s consistent growth, including expansion into new regions, increased service user numbers, and brand strengthening across various sales points of the affiliated credit unions, alongside improved financial performance. These observations confirm the persistent tension between internal and external legitimacy in the case under study, which significantly contributed to the decision to disaffiliate.

4.2.4. Unity versus Diversity

The first indicator of unity within IntegraCoop is the mandatory use of the brand, as evidenced by public information on the IntegraCoop website and corroborated by documents that mandate this branding requirement. This adherence was further confirmed through observations of the electronic environments of individual credit unions.

Interview data shows that efforts to foster unity were mirrored internally at the governance level. The governance framework and processes of IntegraCoop were designed to encourage consensus among participants, which has generally been successful according to the collected reports. Representatives from Aurora Union frequently perceived and acknowledged this consensus, indicating its prevalence.

Further information from IntegraCoop representatives reveals that their strategy for achieving consensus focused on aligning with the convergent characteristics of the participants, aiming to cater to the majority’s needs as a way to promote unity. This approach consistently emphasizes the identification and support of objectives that converged across the network, prioritizing skills and resources that benefit the collective. Nevertheless, this pursuit of unity in objectives, particularly those that enhance network-level competencies, faced challenges due to the diversity among the credit unions. The asymmetries not only affected the effectiveness of the network but also brought to light varying perceptions of interdependence among the members. The evidence suggests that while the strategies aim to unify, the inherent differences among credit unions occasionally hindered these efforts, impacting overall network effectiveness:

“This duality of independence they have acting alone, different from the cooperative center one, is difficult to manage. Moreover, the more credit unions you have, the more difficult this exercise is because the singularity is very strong. Their attempt to make the local model predominate is very strong, you know? We keep talking about the issue of goal convergence. We must converge on goals to get where IntegraCoop wants”.(Tiago)

Interviewees from Aurora Union point out that, during discussions with IntegraCoop, these asymmetries challenged the network’s unity, even if the strategies implemented to ensure that unity helped mitigate these effects. The approach to managing these asymmetries evolved over time. Initially, the focus was on accommodating the individual needs and characteristics of individual credit unions, but it shifted towards enhancing overall effectiveness and optimizing resources at the network level.

Representatives from IntegraCoop note that while efforts to promote unity have been effective in addressing the direct impacts of asymmetries, they inadvertently limit the benefits that diversity brings. IntegraCoop did not perceive the individual resources and characteristics of credit unions as positive, as one executive highlighted:

“For example, Credit Union A has a business structure that will soon have the same level as IntegraCoop’s. You often hear that they have even more knowledge than IntegraCoop. Another Credit Union B on the subject of, for example, Compliance. Soon, it will believe, or others will see, that it has another structure at the same level or more than the one from IntegraCoop”.(Rafael)

This scenario illustrates that while attempts to ensure unity are crucial, they also reduce the potential to leverage the diverse resources and advantages inherent in individual credit unions. This dynamic underscores a significant tension between unity and diversity within IntegraCoop, as the efforts to maintain cohesion sometimes overshadowed the value brought by the unique contributions of its members. As a direct outcome of this tension, Aurora Union chose to cease collaboration with IntegraCoop.

Our findings are summarized in Table 3, which outlines the four identified tensions and how they manifested within the network under study. For each tension verified, the table details its influence on the decision to leave the network.

Table 3.

Synthesis of findings.

5. Discussion

Our findings confirm the empirical presence of four governance tensions in the case studied, consistent with previous research by Provan and Kenis (2008), Saz-Carranza and Ospina (2011), and Schmidt et al. (2019). Notably, regarding the tension between decision-making efficiency and participant inclusion, there was no direct evidence linking this tension to the decision to disaffiliate. Although the excessively hierarchical process and the need to revisit decisions caused some discomfort and potentially impacted the speed and cost of decision-making, these factors did not significantly influence the choice to leave.

The investigation revealed that asymmetries between participating organizations were a predominant underlying cause of the remaining tensions. The deficiencies in the network’s effectiveness, which prevented the credit union from acquiring network-level competencies, were primarily due to asymmetries between the participating organizations. Previous literature suggests that disparities in power and resources often drive organizations to leave networks (Gulati and Sytch 2007; Gulati et al. 2011; Baraldi et al. 2012; Huxham et al. 2000). At IntegraCoop, the inability to manage these asymmetries significantly exacerbated three tensions: flexibility versus stability, internal legitimacy versus external legitimacy, and unity versus diversity. These tensions decisively influenced Aurora Union’s determination to disaffiliate, as its individual needs frequently went unmet due to a lack of flexibility, sometimes undermining unity and at other times internal legitimacy.

The difficulty in meeting individual needs was a significant reason for Aurora Union’s decision to leave. Challenges in managing asymmetries exposed flaws that reduced the network’s effectiveness, triggering tensions between unity and diversity, as well as internal and external legitimacy, and flexibility and stability. McNamara et al. (2019) demonstrate that the most prominent causes for the failure of collaboration in the context of interorganizational networks are the low representation of some participants and the difficulty of contextual interpretation due to cultural issues or consonance of objectives. Aurora Union was unable to realize the expected benefits of participating in IntegraCoop, ultimately leading to its decision to disaffiliate. This issue extended beyond IntegraCoop’s internal environment, influencing its members to the extent that they ceased doing business with the network.

It is discernible that the reasons for Aurora Union’s disaffiliation could have been anticipated during its initial evaluation for affiliation with IntegraCoop. Our findings reveal shortcomings even in the entry process, which overlooked the significance of asymmetries among participants. Recognizing these asymmetries is crucial when selecting participants, as they significantly impact network dynamics. While asymmetries were not directly cited as causes for the specific tensions between unity and diversity, stability versus flexibility, or internal and external legitimacy, IntegraCoop’s inability to manage and balance differences among credit unions critically contributed to these tensions. In this case study, the disparities among participants emerged as a decisive element in triggering the three pivotal tensions.

The results of this study corroborate Schmidt et al.’s (2019) observations that inefficiencies in the decision-making process adversely affect network effectiveness. Consistent with the critical factors they identify, both the number of members and the competencies at the network level emerged as significant sources of tension. It is important to note, however, that the tension between decision-making efficiency and participant inclusion, while present, did not influence Aurora Union’s decision to disaffiliate.

Our findings regarding the tension between flexibility versus stability offer a nuanced perspective that both differs from and complements the findings of Chen (2021). While they highlight the positive effects of flexible governance design on enhancing network stability, our study demonstrates that inflexible governance structures can detrimentally affect network flexibility. A key difference in our findings is related to the impact of flexibility on network stability. Unlike Chen (2021), who notes that increased flexibility could positively influence stability, our study does not find evidence to support this relationship.

The results about the tension between internal and external legitimacy do not confirm the findings of Kim and Choi (2021). Integration and collaboration between participants are not sufficient to guarantee internal legitimacy, as the authors observe in their chosen field. In terms of external legitimacy, our study did not detect significant influences from structural dimensions regarding this aspect. Contrary to Romiti et al. (2020), who suggest that the NAO governance model might effectively balance external and internal legitimacy, such a trend was not evident in our case. The tension between these two forms of legitimacy was pronounced and, according to our findings, significantly contributed to explaining Aurora Union’s decision to disaffiliate from IntegraCoop.

In terms of the tension between unity versus diversity, our findings are in line with those of Maron and Benish (2022), with both studies indicating that unity can negatively impact diversity. Practices to enforce unity, as Saz-Carranza and Ospina (2011) propose, may compromise network effectiveness and diminish diversity. This specific tension played a direct role in Aurora Union’s decision to leave the network, as IntegraCoop’s pursuit of unity entailed a lesser prioritization of maintaining diversity within the network.

6. Conclusions

This study explores the phenomenon of an organization’s departure from an interorganizational network through the lens of network governance tensions, as proposed by Provan and Kenis (2008) and Saz-Carranza and Ospina (2011). The empirical context focuses on a single credit union that ceased its participation in a cooperative center governed by an NAO-type mode after approximately two years. This investigation highlights the critical role that governance tensions play in influencing an organization’s decision to disaffiliate, underscoring the complexities of maintaining collaboration within such networks.

From a theoretical perspective, our research enriches the existing literature on network governance by delineating the mechanisms through which governance tensions impact interorganizational networks and their member organizations. Our findings not only align with but also extend previous studies by Schmidt et al. (2019), Maron and Benish (2022), and Chen (2021), by demonstrating specific manifestations and detrimental effects of such tensions in a novel empirical context. Most notably, our analysis explains how tensions between flexibility and stability, external and internal legitimacy, as well as between unity and diversity, compromise network effectiveness and impair the operational capabilities of the involved organizations. Crucially, we establish a causal link between these three governance tensions and organizational decisions to disaffiliate, thereby providing a pivotal theoretical contribution that outlines the potential extremities of governance conflicts within interorganizational networks—which had not yet been examined in extant literature (van den Oord et al. 2023).

Concerning managerial contributions, this study offers valuable recommendations for single credit unions either already affiliated with or considering joining a cooperative center, as well as for the cooperative centers themselves. Single credit unions join networks seeking various benefits, from reduced operational costs to gains in scale and in revenue. However, for these benefits to materialize, the decision to affiliate must be approached with caution. One pivotal lesson from this study is the critical nature of the affiliation decision. Beyond identifying needs to be met, a credit union’s intentions for joining must be explicitly clear. If a credit union’s goals conflict with the cooperative center’s need for unity, as demonstrated in the case studied, it can adversely affect all members involved.

This research is subject to several limitations. First, it involves a retrospective analysis of a specific case, which prevented real-time data collection. Our analysis relied on a recollection of reports, documents, and interviews which are not free from biases. Second, being a single case study limits the generalizability of the findings. Future research could benefit from a multiple case study approach or other methodologies that allow for a broader observation of empirical contexts. This could yield more comprehensive results or reveal novel theoretical insights. Additionally, pre-testing research protocols with respondents could enhance the clarity and precision of the data collected.

As suggestions for future studies, a deeper exploration into the tension between internal and external legitimacy within networks is recommended. Although this study did not capture all elements related to external legitimacy, further research could develop this field more thoroughly. Additionally, investigating the interrelationships between elements of governance tensions in interorganizational networks could provide valuable insights. Future work might specifically focus on the interactions and potential synergies among the elements that constitute the four identified tensions in network governance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.A.; Methodology, G.A. and A.B.; Investigation, G.A.; Data curation, G.A. and A.B.; Formal analysis, G.A., A.B. and D.W.; Validation, A.B. and D.W.; Project administration, G.A.; Writing—original draft, G.A. and A.B.; Writing—review & editing, A.B., D.W. and G.A.; Visualization, G.A., A.B. and D.W.; Supervision, D.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research did not involve personal information or sensitive data of the interviewees, so it was not necessary to submit it to the ethics committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study. The study and its purpose were explained to all the respondents who participated in this study. The anonymity and confidentiality of the data were maintained at all times.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | Fictitious names were adopted both for the cooperative center and credit union to preserve anonymity. |

References

- Baraldi, Enrico, Espen Gressetvold, and Debbie Harrison. 2012. Resource interaction in inter-organizational networks: Foundations, comparison, and a research agenda. Journal of Business Research 65: 266–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. 1971. Lei nº 5.764, de 16 de Dezembro de 1971. Define a Política Nacional de Cooperativismo, Institui o Regime. Jurídico das Sociedades Cooperativas, e dá Outras Providências. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l5764.htm (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Brasil. 2022. Lei Complementar nº 196, de 24 de Agosto de 2022. Altera a Lei Complementar nº 130, de 17 de abril de 2009 (Lei do Sistema Nacional de Crédito Cooperativo), para Incluir as Confederações de Serviço Constituídas por Cooperativas Centrais de Crédito Entre as Instituições Integrantes do Sistema Nacional de Crédito Cooperativo e Entre as Instituições a Serem Autorizadas a Funcionar pelo Central Bank of Brazil; e dá Outras Providências. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/Leis/LCP/Lcp196.htm (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Camarinha-Matos, Luis M., and Arturo Molina. 2010. Trust, value systems and governance in collaborative networks. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing 21: 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camelo, Felipe, José Afonso Queiroz, Lucio César de Faria, and Marcelo Carfora. 2021. Integração Sistêmica das Cooperativas Independentes: Expectativas e desafios. Available online: https://www.mundocoop.com.br/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Integrac%CC%A7a%CC%83o-Siste%CC%82mica-das-Cooperativas-Independentes.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2022).

- Central Bank of Brazil. 2022. Panorama do Sistema Nacional de Crédito Cooperativo. Available online: https://www.bcb.gov.br/estabilidadefinanceira/coopcredpanorama (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Chen, Jinhua. 2021. Governing collaborations: The case of a pioneering settlement services partnership in Australia. Public Management Review 23: 1295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagnino, Giovanni Battista, Gabriella Levanti, Anna Mina, and Pasquale Massimo Picone. 2015. Interorganizational network and innovation: A bibliometric study and proposed research agenda. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 30: 354–77. [Google Scholar]

- De Pourcq, K., and K. Verleye. 2022. Governance dynamics in inter-organizational networks: A meta-ethnographic study. European Management Journal 40: 273–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortes, Marcos Vinícius Bitencourt, Lara Agostini, Douglas Wegner, and Anna Nosella. 2023. Paradoxes and Tensions in Interorganizational Relationships: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 16: 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, Ranjay, and Martin Gargiulo. 1999. Where do interorganizational networks come from? American Journal of Sociology 104: 1439–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, Ranjay, and Maxim Sytch. 2007. Dependence asymmetry and joint dependence in interorganizational relationships: Effects of embeddedness on a manufacturer’s performance in procurement relationships. Administrative Science Quarterly 52: 32–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, Ranjay, Dovev Lavie, and Ravindranath Madhavan. 2011. How do networks matter? The performance effects of interorganizational networks. Research in Organizational Behavior 31: 207–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harini, K. N., and Manoj T. Thomas. 2021. Understanding interorganizational network evolution. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 36: 2257–75. [Google Scholar]

- Huxham, Chris, Siv Vangen, and Colin Eden. 2000. The challenge of collaborative governance. Public Management an International Journal of Research and Theory 2: 337–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvenpaa, Sirkka Liisa, and Liisa Välikangas. 2022. Toward temporally complex collaboration in an interorganizational research network. Strategic Organization 20: 110–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Yusoon, and Thomas Y. Choi. 2021. Supplier relationship strategies and outcome dualities: An empirical study of embeddedness perspective. International Journal of Production Economics 232: 107930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Seulki. 2022. When tensions become opportunities: Managing accountability demands in collaborative governance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 32: 641–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maron, Asa, and Avishai Benish. 2022. Power and conflict in network governance: Exclusive and inclusive forms of network administrative organizations. Public Management Review 24: 1758–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, Madeleine W., Katrina Miller-Stevens, and John C. Morris. 2019. Exploring the determinants of collaboration failure. International Journal of Public Administration 43: 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooteboom, Bart, Hans Berger, and Niels G. Noorderhaven. 1997. Effects of trust and governance on relational risk. Academy of Management Journal 40: 308–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoselova, Olga A. 2022. What matters for interorganizational connectedness? Locating the drivers of multiplex corporate networks. Strategic Management Journal 43: 872–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provan, Keith G., and Patrick Kenis. 2008. Modes of network governance: Structure, management, and effectiveness. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18: 229–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romiti, Anna, Mario Del Vecchio, and Gino Sartor. 2020. Network governance forms in healthcare: Empirical evidence from two Italian cancer networks. BMC Health Services Research 20: 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, Ana Lúcia, Douglas Wegner, José Antônio Valle Antunes Júnior, and Antonio Domingos Padula. 2012. Diferenças e inter-relações dos conceitos de governança e gestão de redes horizontais de empresas: Contribuições para o campo de estudos. Revista de Administração (São Paulo) 47: 112–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saz-Carranza, Angel, and Sonia M. Ospina. 2011. The behavioral dimension of governing interorganizational goal-directed networks—Managing the unity-diversity tension. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 21: 327–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saz-Carranza, Angel, Susanna Salvador Iborra, and Adria Albareda. 2016. The power dynamics of mandated network administrative organizations. Public Administration Review 76: 449–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, Joel Ricardo Rocha, Dougla Wegner, and Marcos Vinícius Bitencourt Fortes. 2019. A governança de redes interorganizacionais: Uma análise da tensão entre eficiência e inclusão no processo decisório. Revista de Empreendedorismo e Gestão de Pequenas Empresas 8: 319–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipilov, Andrew. 2012. Strategic multiplexity. Strategic Organization 10: 215–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stake, Robert E. 2016. Pesquisa Qualitativa: Estudando Como as Coisas Funcionam. Porto Alegre: Penso Editora. [Google Scholar]

- Stoker, Gerry. 1998. Governance as theory: Five propositions. International Social Science Journal 50: 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahlne, Jan-Erik, and Jan Johanson. 2021. Coping with complexity by making trust an important dimension in governance and coordination. International Business Review 30: 101798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Oord, Steven, Patrick Kenis, Jorg Raab, and Bbart Cambré. 2023. Modes of network governance revisited: Assessing their prevalence, promises, and limitations in the literature. Public Administration Review 83: 1564–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Huanming, and Bing Ran. 2022. Network governance and collaborative governance: A thematic analysis on their similarities, differences, and entanglements. Public Management Review 25: 1187–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, Douglas, Aurora Carneiro Zenn, and Byron Fabrício Acosta Andino. 2011. O último que sair apaga as luzes: Motivos para a desistência da cooperação e encerramento de redes de empresas. Revista de Negócios 16: 30–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Robert K. 2009. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Newcastle upon Tyne: Sage, vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).