Abstract

This study examines the impact of international trade activities on employment in the Portuguese textiles and apparel industry from 2010 to 2017. It finds evidence that imports and exports have a persistent, negative, and significant effect on overall job creation, with this impact intensifying over the long-run. Additionally, the increasing elasticity of substitution between imports and exports indicates that private companies of this industry have benefited from a win–win situation characterised by higher production volumes and lower marginal costs. By applying an unsupervised machine-learning method, followed by a discrete choice analysis to infer the firm-level propensity to possess green capital, we identify a phenomenon termed the green international trade paradox. This study also reveals that international trade activities positively influence green job creation in firms lacking green capital if and only if these players are engaged in international markets while negatively affecting firms already endowed with green technologies. As such, empirical results suggest that the export-oriented economic model followed over the last decade by the Portuguese textiles and apparel industry has not necessarily generated new domestic employment opportunities but has significantly altered the magnitude and profile of skill requirements that employers seek to identify in new workforce hires.

1. Introduction

The textiles and apparel industry (TAI) is a vital component of the European economy, playing a significant role in both employment and international trade. The European Commission (EC) reports that exports of textiles and apparel from the European Union (EU) account for more than 30% of the world’s total market exports (EC 2015a). Although currently dealing with a negative trade balance, exports (imports) of the TAI in European member states are growing on average at a rate of 13% (4%), respectively (EC 2015a). In addition to the evidence of convergence in the trade balance, European TAIs are gaining international prominence due to their size, quality, design, flexibility, and innovation in new products. The EC has been responsible for this outstanding performance, as it guarantees a level playing field through the application of Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) and World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules, while simultaneously being actively engaged in third-party dialogues (e.g., Colombia, China) on sensitive topics such as industrial and regulatory policies (EC 2015b).

Within the European territory, emphasis is given to the Euro-Mediterranean Dialogue on the Textile and Clothing Industry (EUROMED), which was launched in 2014 (EUROMED 2014). This agreement is not only the unique industry-based dialogue celebrated between Mediterranean countries, but it is also extremely important as a driver of economic growth, social development and political stability for the Euro-Mediterranean region. Indeed, EC (2015b) reports that the trade value of TAIs in this European area amounts to €35 billion per year and 35% of EU products have this region as final destination. Unsurprisingly, the TAI is considered the second-most relevant industry after oil and gas in this transnational jurisdiction from Europe. The Euro-Mediterranean region also has a strategic role by ensuring the possibility to maintain the entire production chain geographically located in the European territory, thereby enabling the persistence of onshoring practices and the promotion of cost savings. The European Skills Council (ESC) recognises that European TAIs are experiencing a renaissance era marked by innovation and technical developments, which are affecting several business organisations (ESC 2014).

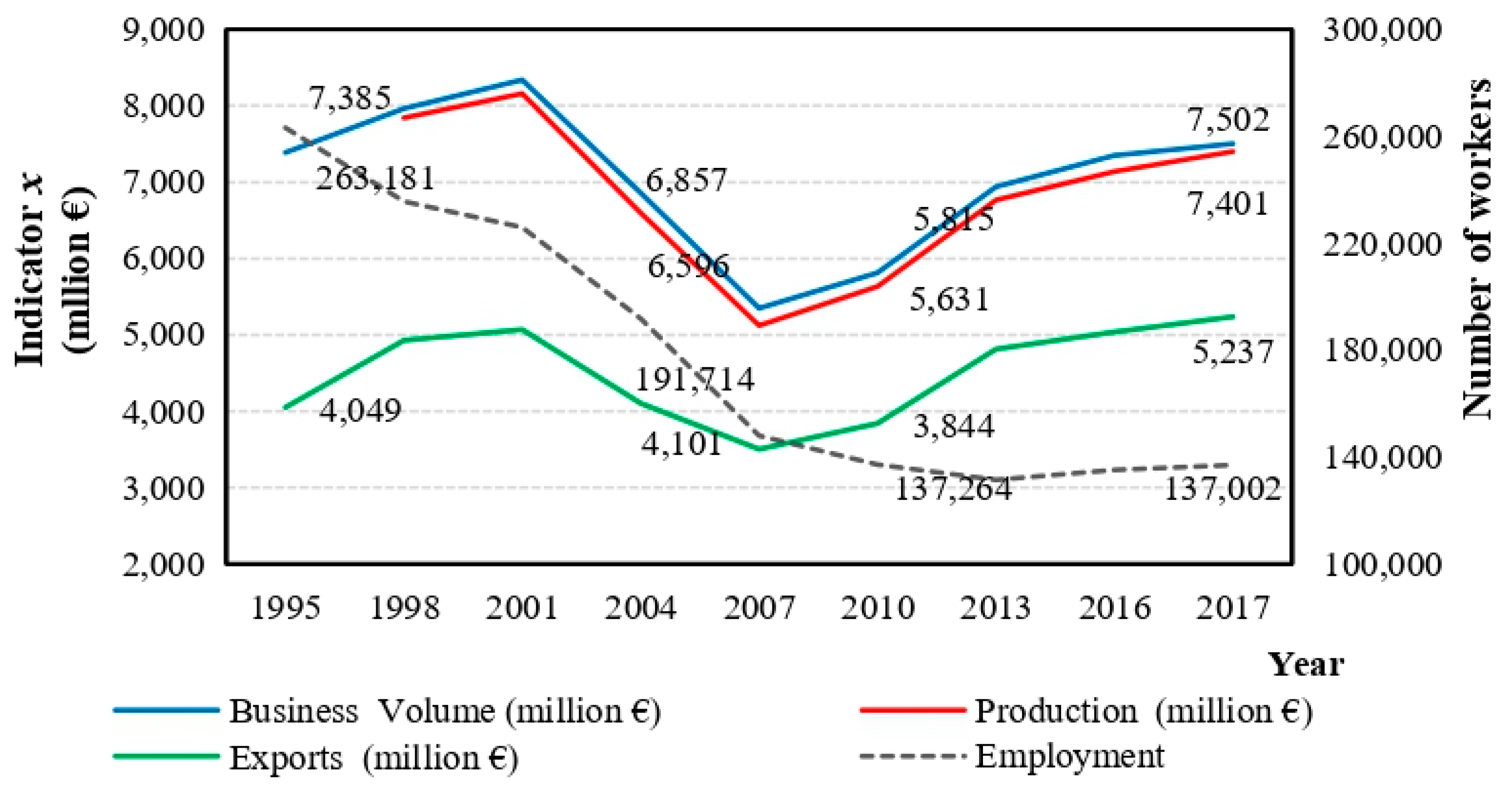

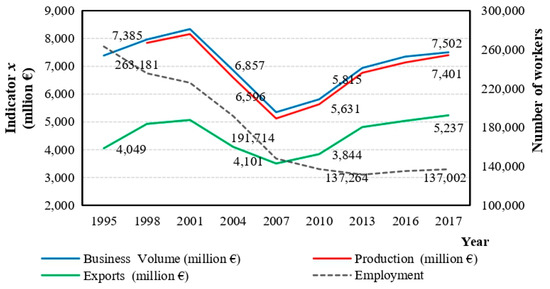

This shift in paradigm has been particularly visible in Portugal. Since China’s entry into the WTO in 2001, and by the end of the Multi-Fiber Agreement in 2005, the Portuguese textiles and apparel industry (PTAI) lost more than 100,000 jobs, which created a need to reinvent it. After a decade and a half, the PTAI seems to have recovered in fundamental indicators. As clarified in Figure 1, this industry has contributed nearly €7.2 billion in terms of production to the national gross domestic product (GDP) and generated a private spending on goods and services of approximately €7.3 billion by the end of 2016. It also employed more than 135,000 workers, which is almost 20% of the total manufacturing employment in Portugal. Associação Têxtil e de Vestuário em Portugal (ATP), which is the most relevant association of textiles and apparel in the country, confirms that the total number of employees increased almost 3% between 2015 and 2016 (ATP 2018).

Figure 1.

Evolution of key indicators in the PTAI (1995–2017). Source: own development based on data from ATP (2018).

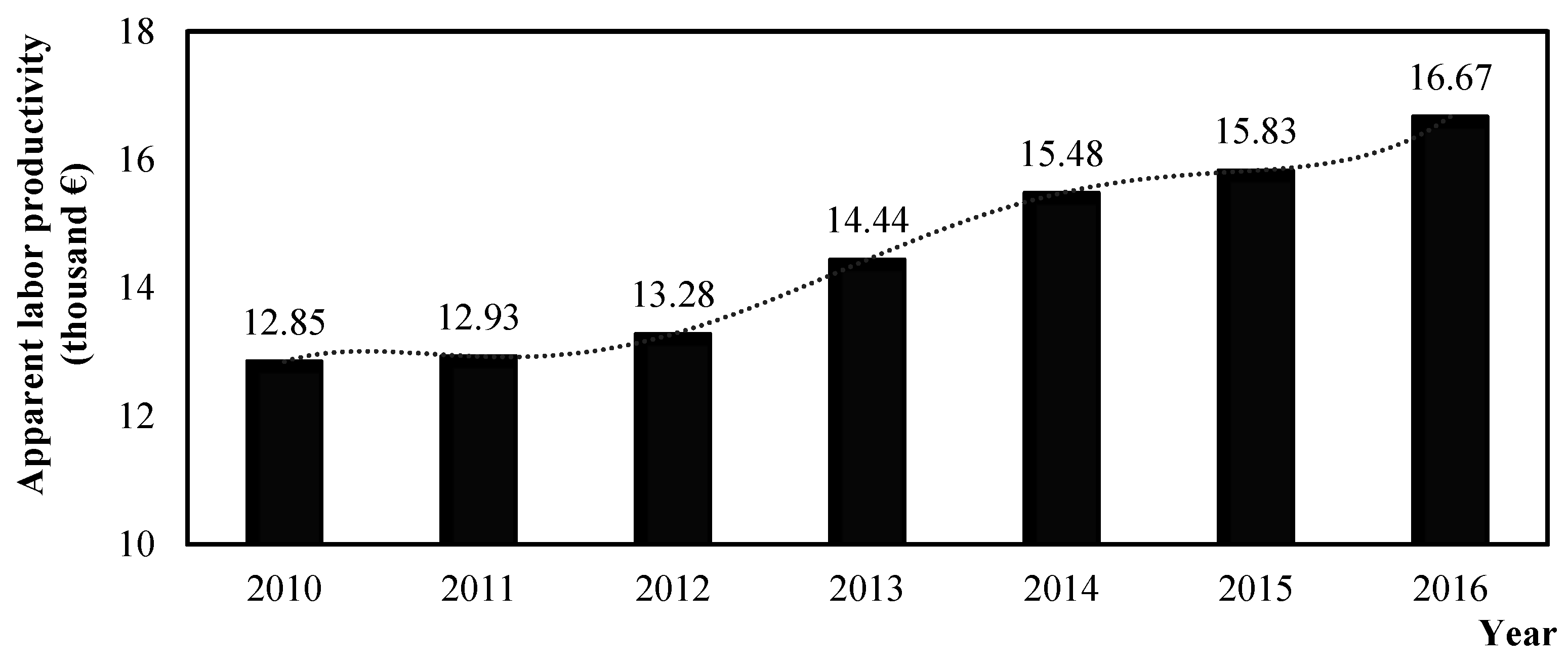

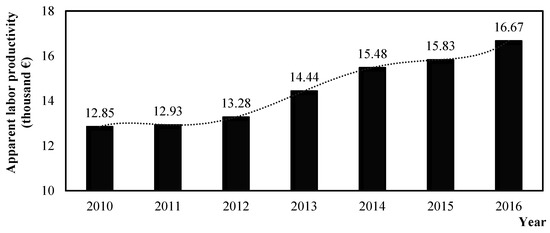

Moreover, this evolution is not only felt in absolute value but also in relative terms. Figure 2 shows the evolution of PTAI’s apparent labour productivity during the 2010–2017 period. This economic indicator has evolved positively, going from €12.8 thousand to €16.7 thousand between 2010 and 2016. Nevertheless, ATP (2018) reports that such a threshold remains below the national average, which was €23.1 thousand in 2016. This productivity gain has been complemented by the improvement in several domains of the economic activity, such as industrial know-how and technological innovations, upgrade of design and quality attributes, quicker time-to-market responses, higher degree of flexibility and reliability, creation of added value services, and development of structured and dynamic clusters backed up by competence centres (Hodges and Link 2019). Furthermore, despite the relevance of Europe as the main destination market for goods and services created by PTAI companies, ATP (2018) clarifies that the United States of America (USA) is becoming a relevant destination market for Made in Portugal products. As such, two stylised facts seem to characterize the evolution of PTAI since 2010:

Figure 2.

Evolution of the apparent labour productivity in the PTAI (2010–2016). Source: own development based on data from ATP (2018)1.

- The recovery of this industry relied on a significant increase in exports; and

- There was a downward trend in the number of workers, which has been slightly reversed in recent years.

Nevertheless, it is relevant to highlight that the literature focused on assessing the dynamics of TAIs has been silent about two aspects:

- Generically, on clarifying the association of the relation between international trade activities (i.e., imports and exports) and employment growth opportunities; and

- For the case of PTAI companies, on identifying explanatory variables with significant impact on employment or, equivalently, drivers behind the persistence (reversal) of job destruction between 2010 and 2014 (2015 and 2017), respectively.

Although several reasons may be pointed out from a theoretical point of view (e.g., efforts to enhance the product innovation through technological developments; greater agility and organisation, while maintaining the experience of old guard entrepreneurs combined with the technical knowledge of a new generation of managers), the unique conclusion expressed by specialists so far is that PTAI companies tend to operate sub-optimally, relative to firms from different manufacturing industries (Marques and Guedes 2016). Motivated by this fact, firm-level data were collected to satisfy the research gap of identifying whether international trade activities have a significant impact on employment in the PTAI during the period 2010–2017. In this body of literature, recent studies present differing views on the impact of international trade activities in the TAI. Some studies emphasize negative outcomes, such as layoffs and plant closures (Kabish 2023; Ruteri 2023; Majumder and De 2023), while others highlight opportunities for innovation and adaptation in response to the evolving global environment (Keough and Lu 2021; Khan et al. 2022; Lu 2022a, 2024a, 2024b; Laurits and Lu 2023; Botwinick and Lu 2023; Carswell and De Neve 2024).

Additionally, this study brings the novelty of analysing the impact of international trade on employment by differentiating between employment defined in a broad sense and green employment. Employment in the EU-28 environmental economy rose from 2.8 million full-time equivalents (FTEs) in 2000 to 4.5 million FTEs in 2016, generating €746 billion of output and €303 billion of value added in 2016 (Eurostat 2022). These trends in employment and value added indicate considerably faster growth than that observed in the GDP. Moreover, ILO (2018) claims that actions to limit global warming up to 2 degrees Celsius will create more than 6 million green jobs worldwide. Like other environmentally concerned industries, the PTAI helps manage pollution and natural resources, covering inter alia resource efficiency, waste management, air pollution, controlling and cleaning up soil, as well as recycling, renewable energy, low carbon footprint, and water supply. Green employment also accommodates economic activities such as the design of sustainable clothing, eco-production, and many other jobs, which are impacted indirectly. In this sense, the growth of green employment can be interpreted as a challenge for enabling PTAI’s sustainable development.

Knowing that the promotion of this industry in international markets is currently viewed as a priority to consolidate the global relevance of Portugal, the main goal of this study is to understand the effect of international trade on employment in the PTAI by applying a panel data analysis and several extensions based on unsupervised machine learning, discrete choice, and limited dependent variable models. Since the final sample consists of 5557 registered firms, this research guarantees the extrapolation of richer information relative to past studies. In this body of literature, recent studies have focused on a variety of institutional elements as determinants of the green transition. These include the impact of renewable raw material sourcing, production re-evaluation, and recycling methods (Brydges 2021; Hartley et al. 2022); the mediating role of product innovation in the relationship between economic performance and green entrepreneurial orientation (GEO) and green transformational leadership (GTL) (Asad et al. 2024); the urgent need for updated infrastructure and cutting-edge vital inputs (Tumpa et al. 2019; Virtanen et al. 2019; Sandvik and Stubbs 2019; Todeschini et al. 2020); the impact of internal pressures, such as process innovation and digitalisation (Yang et al. 2023), and external pressures, such as environmental regulations and media (Kazancoglu et al. 2021; Andersén 2021; Bressanelli et al. 2022; Reike et al. 2023); and the impact of information sharing among employees (Cao et al. 2019). It is also remarkable that the recent penetration of gaming elements (e.g., avatars) into the TAI has prompted an empirical analysis of the mediating role of brand coolness on the equity maintained by TAI companies (Salem et al. 2023). Notably, none of these recent studies have addressed the impact of international trade on green capital endowment and green job creation, nor have they analysed whether green capital significantly mediates the relationship between green employment and international trade. Motivated by this gap and using data from the PTAI, this study aims to address three key research questions:

- What is the relationship between green capital endowment and international trade? Is this relationship statistically significant? What is the impact of exports and imports on the proliferation of green capital in the PTAI?

- What is the relationship between green job creation and international trade? Is this relationship statistically significant? What is the impact of exports and imports on the proliferation of green jobs in the PTAI?

- Does green capital mediate the relationship between green employment and international trade in the PTAI?

The goal is to complement ongoing research on the TAI, which often concentrates on specific organisational aspects, by examining how international trade activities impact the effectiveness of the green transition in terms of both green employment and green capital.

Methodologically, this study has the concern to control for the presence of heteroscedasticity and endogeneity. Initially, it performs a panel data analysis to infer the impact of international trade activities on the proliferation of employment defined in a broad sense. Afterwards, it uses an unsupervised machine-learning method to capture a proxy of green capital and green employment and then executes statistical inference to understand the role of international trade activities on the penetration of green employment by considering a two-step approach that consists of adopting a discrete choice analysis to estimate the likelihood of firms’ green capital adoption followed by the application of several limited dependent variable models, while controlling for the presence of self-selection bias, to infer the firm-level propensity to create green jobs. Finally, it performs a mediation analysis to identify statistically significant mediators of the relationship between green employment and international trade.

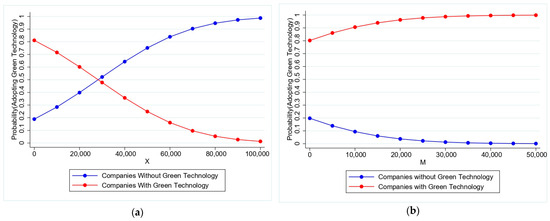

The main results can be summarised as follows. Firstly, the analysis demonstrates that international trade activities have a permanent, negative, and significant effect on job creation when this is defined in a broad sense. This is confirmed through the identification of the mechanism through which PTAI companies benefit from the appropriation of knowledge spillovers when they interact with international peers. Although globalisation ensures the absorption of technological progress, this is being used by PTAI companies to satisfy alternative ends other than promoting new employment opportunities. Moreover, the negative impact of exports and imports is unambiguously stronger in the long-run, which implies that public policy measures conceived to support this industry should not be characterised by structural breaks after their initial uptake. Secondly, this study confirms that the imposition of geographical restrictions on international trade activities do not necessarily lead to a stronger negative effect on PTAI’s job creation. In light of the recent pandemic that affected the world, this result suggests that employment opportunities in the PTAI tend to face less adverse effects compared to other manufacturing industries. Thirdly, we provide evidence that exports and imports have a stronger impact on employment in companies located in the north of Portugal and whose juridical form is representative of a greater realisation of own capital, which may legitimize the imposition of discriminatory clauses when deemed necessary, proportionate, and appropriate. Fourthly, results suggest that international trade activities do not necessarily create green jobs in companies endowed with green capital. However, differently from the case of employment defined in a broad sense, as companies without green capital have been able to participate in international trade, this stylised fact has allowed to maintain a stabilised level of employment from 2015 onwards. In this context, a discussion is presented to claim that better targeting and coordination of labour market measures and tools are essential to create the necessary conditions to support green employment in the PTAI, bridge skill gaps and labour shortages, and anticipate changes in human capital needs. Results also confirm that international trade activities have a positive (negative) and significant effect on the creation of green jobs in firms without (with) green capital, respectively. This is not only indicative of a short-run transition that may reflect a structural transformation of this industry due to marginal productivity gains caused by the penetration of green technologies, but also reflects that niche employment opportunities are being created, some traditional jobs are being replaced, and others are being relocated to firms without green capital if and only if these have the chance to participate in international markets. Overall, the results of this study suggest that the economic model oriented to exports followed the last decade by the PTAI does not necessarily promote new employment opportunities in the domestic market, but it has contributed to modifying the profile of skills required of the labour force.

The manuscript has the following organisation: Section 2 presents a literature review, clarifies research hypotheses, and provides a mathematical background to support the empirical approach. Section 3 displays econometric details. Results are clarified in Section 4. A discussion is presented in Section 5. Conclusions are presented in Section 6. Appendix A, Appendix B and Appendix C contain details not exposed in the main text for the sake of brevity.

2. Theory

2.1. Literature and Research Hypotheses

This study quantifies the impact of international trade activities on employment and green employment in the PTAI. Since this research goal necessarily requires the comprehension of several conceptual elements, an exhaustive literature review has been relegated to Appendix C for the sake of brevity. We divide it into smaller parts as follows:

- General effects of the 2005 international trade’s liberalisation on employment;

- Role of the international trade on employment;

- Role of firm-specific characteristics on employment;

- Past contributions focused on evaluating determinants of employment in the TAI; and

- Employment defined in a broad sense vs. the penetration of green employment.

2.1.1. Impact of the TAI’s Internationalisation on Employment

The first point discusses that the TAI’s internationalisation has had a profound impact on employment, particularly following trade liberalisation after 2005. The TAI is widely regarded as a key pillar of the global economy, significantly contributing to job creation and economic growth, especially in low- and middle-income countries (Eppinger 2022). Additionally, this industry plays a crucial role in increasing household income and providing access to affordable clothing for economically disadvantaged households (Xu et al. 2024).

However, the rapid expansion of the TAI has led to pressing sustainability challenges (Millward-Hopkins et al. 2023). The industry’s product lifecycle tends to be short, while its global supply chain is highly fragmented, with competitive advantages often centred around product design and style differentiation (Tumpa et al. 2019). Textile production processes are also energy-intensive and rely on chemicals that present significant environmental concerns (Reike et al. 2023). Developed countries, particularly in Europe and the USA, have witnessed considerable declines in their manufacturing sectors, largely due to competition from low-cost producers in developing countries. A significant consequence has been the sharp drop in employment, particularly in low-skilled jobs. The lack of adequate training programs at the company level has also emerged as a barrier to the adoption of environmentally sustainable innovations within organisations. This, in turn, has resulted in a shortage of a skilled workforce capable of effectively implementing decarbonisation and circularity practices (Todeschini et al. 2020). Mishra et al. (2023), underscoring the critical need for training both managers and workers to ensure alignment with technological advancements and operational improvements.

It is not surprising, then, that researchers hold differing views on the impact of international trade activities in the TAI. Some researchers focus on the negative outcomes, such as layoffs and plant closures (Kabish 2023; Ruteri 2023; Majumder and De 2023), while others highlight the potential for innovation and adaptation to the evolving global environment (Keough and Lu 2021; Khan et al. 2022; Lu 2022a, 2024a, 2024b; Laurits and Lu 2023; Botwinick and Lu 2023; Carswell and De Neve 2024). In light of these findings, we adopt the optimistic perspective and propose the following hypothesis:

H1.

The elasticity of substitution of imports by exports has a positive effect on employment.

This hypothesis aligns with the notion that the trade-off between imports and exports in the PTAI may positively impact employment, as companies adjust to international trade dynamics by adapting their workforce and production processes.

2.1.2. Role of Geographical Reach and Scope

The second point addresses the role of geographical reach and scope in shaping how international trade affects employment in the TAI. Past evaluations, using the Heckscher–Ohlin–Samuelson (HOS) framework, suggest that trade liberalisation typically leads to a redistribution of employment between import-substitute sectors and export-oriented sectors. In this framework, import growth often results in job losses in domestic industries, while export expansion boosts employment by creating new opportunities in global markets. However, the literature remains divided on whether the overall net effect of international trade on employment is positive or negative, particularly due to the shifting demands for different types of skills required for modern jobs. One of the key issues in this debate is the transformation of the labour market within the TAI, where globalisation has driven companies to adopt new technologies and business models that alter the traditional skills required for employment. As firms engage in international trade, they face pressures to adapt to global standards, often resulting in a demand for higher-skilled workers while reducing the reliance on lower-skilled labour (Xu et al. 2024). This shift in skill requirements complicates the assessment of trade’s net impact on employment, as it may increase job opportunities for some while causing displacement for others.

Additionally, the sustainability agenda plays a significant role in shaping the geographical scope of TAI companies’ operations (Eppinger 2022). It is widely accepted that the TAI must address environmental challenges comprehensively and transition towards sustainable practices. For instance, TAI companies have increasingly adopted decarbonisation strategies aimed at reducing carbon emissions throughout their supply chains (Guo et al. 2024). These efforts include shifting from a linear business model to a circular economy model, which extends product lifecycles, enhances recycling of second-hand clothing, and fosters new employment opportunities by creating jobs in recycling and circular production processes (Hartley et al. 2022).

Moreover, the geographical reach of a firm’s international trade activities is critical to its ability to absorb the positive spillover effects of international trade on employment (Krugman 1995). Firms with a broad geographic presence can leverage international knowledge, innovations, and market access to enhance job creation. However, companies operating within more geographically restricted markets, such as those limited to EU territories, may find it easier to comply with region-specific regulations and standards, thereby benefiting more directly from the localised nature of trade relationships within the EU. This allows firms to better manage their labour needs and ensure compliance with sustainability goals, especially when it comes to eco-friendly practices. Given the importance of geographical considerations in determining the employment outcomes of international trade, the following hypothesis is formulated:

H2.

Exports and imports have a stronger impact on employment in PTAI companies when international trade activities are geographically restricted to regions inside the EU territory.

This hypothesis posits that limiting trade activities to the EU can amplify the positive employment effects of exports and imports. This is likely due to the closer alignment of trade regulations, labour standards, and sustainability practices within the EU, which may better support employment growth in the PTAI.

2.1.3. Role of Juridical Form and Own-Capital Realisation

The third point explores how firm-specific factors—such as innovation, product differentiation, juridical form, and the skill level of employees—affect employment within the TAI. Research shows that firms adjust differently to global competition based on their size, age, efficiency, and governance structures (Hodges and Link 2019). Moreover, Nouinou et al. (2023) review decision-making processes in Industry 4.0 within the TAI, identifying trends like data-driven, real-time, decentralised, integrated, and sustainable decision-making. These factors, crucial to modern competitive strategies, influence how firms manage employment during transitions to digitalised and globalised production processes.

One of the most crucial factors determining how well firms can adapt to these challenges is their juridical form, which reflects how they are structured in terms of ownership and capital realisation (Ribeiro and Soares 2024). Firms with higher capital endowment are generally better equipped to invest in technological innovations and manage the high fixed costs associated with scaling up production and expanding globally. Smaller firms, or those without sufficient innovation capacity, may struggle to compete and might downsize as a result.2 For instance, in a recent study focused on the PTAI, Santos and Castanho (2022) highlight that smaller firms in the PTAI performed better during periods of global economic crisis compared to larger firms. This was likely due to the higher fixed costs that larger firms face, which makes them more vulnerable to economic downturns when global orders decline. Their analysis also underscores the importance of factors such as management experience and organisational flexibility in determining a company’s resilience during such periods. Moreover, Portugal is one of Europe’s leading textile exporters, and the performance of PTAI firms has implications for the country’s broader economic sustainability. However, Santos and Castanho (2022) overlook a key point: the fact that more than 98% of PTAI firms are small- and medium-sised enterprises (SMEs), which can introduce a self-selection bias in their empirical analysis. Larger firms, with their higher fixed costs, are more likely to perform worse in times of crisis, which skews the empirical results if self-selection is not properly accounted for. Given that juridical form and capital endowment play crucial roles in how firms respond to international trade dynamics and employment demands, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3.

Exports and imports have a stronger effect on employment in PTAI companies whose juridical form is representative of a greater endowment of own capital realisation.

This hypothesis suggests that firms with a juridical form reflecting a higher degree of capital investment are better positioned to leverage the benefits of international trade for employment growth. These firms are more likely to have the financial and technological resources necessary to capitalise on export opportunities and mitigate the negative effects of increased competition from imports.

2.1.4. Role of Clustering and Agglomeration Effects

The fourth point examines the role of agglomeration and clustering effects within the TAI, focusing on various factors influencing employment and the implications of regional concentration. Recently, X. Chen et al. (2024) conducted a systematic review of 68 papers on decarbonisation in textile supply chains. Their study led to the development of a comprehensive conceptual framework that integrates antecedents, decarbonisation practices, influential factors, and outcomes. This review also suggests that regional characteristics, including the countries in which firms operate, play a crucial role in shaping decarbonisation and employment patterns.

A notable aspect of the TAI is the geographical concentration of companies, particularly in Portugal, where firms are clustered into three main regions (ATP 2018). This spatial concentration suggests that the role of regional characteristics and clustering effects should be considered when assessing employment trends and industry dynamics. Moreover, Han and Jeon (2019) and Jeong et al. (2021) claim that understanding the concept of revitalisation and the impact of spatial characteristics is essential for analysing the TAI.

Lu (2022b) also clarifies that while the TAI is global, its trade patterns remain predominantly regional. Countries often engage in import and export activities with partners within the same region (Dicken 2015). Given the exacerbation of this regional concentration, it is crucial to explore how international trade affects employment in the TAI within specific clusters. Consequently, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4.

Exports and imports have a stronger effect on employment in PTAI companies belonging to the North of Portugal.

This hypothesis investigates the differential impact of international trade on employment within various regional clusters, contributing to better understanding the role of clustering and agglomeration effects in the PTAI.

2.1.5. Impact of the TAI’s Internationalisation on Green Jobs

The focus on sustainable development within the TAI has increasingly shifted towards green practices. However, much of the existing research remains theoretical, concentrating on strategies such as renewable raw material sourcing, production re-evaluation, and recycling methods (Brydges 2021). These studies often lack practical applicability and fail to address emerging trends in green employment (Xu et al. 2024). Consequently, the fifth point explores the impact of internationalisation on green jobs, particularly as it pertains to the transition towards sustainable and eco-friendly production practices in the TAI.

Recent literature suggest that GEO has gained prominence over traditional entrepreneurial orientation as a critical factor in enhancing the performance of entrepreneurial firms while mitigating ecological impacts (Muangmee et al. 2021; Asad et al. 2024). GEO focuses on integrating environmental considerations into business practices, which aligns with the broader goals of sustainable development and can influence the creation of green jobs.

Dynamic capability theory (DCT) further supports this notion by explaining how enterprises can adopt, adapt, and innovate in ways that align with consumer preferences and competitive pressures (Hasegan et al. 2018; Zahid et al. 2022; Asad et al. 2024). Accordingly, firms that leverage their dynamic capabilities effectively can enhance their green innovation efforts. This view posits that the ability to develop and share knowledge among employees contributes significantly to green innovation, which is increasingly demanded in the current information era (Cao et al. 2019).

From a resource-based view (RBV), GLT is identified as a vital resource that significantly impacts the performance of entrepreneurial firms (Barney 1991). Effective use of organisational resources can lead to superior performance, especially in green product innovation, which necessitates a focus on environmental preservation (Andersén 2021). Past literature has examined green entrepreneurial orientation and GTL independently, as well as dynamic capabilities and RBV approaches as separate constructs (Hamdoun 2020).

The growing emphasis on green employment is evident from international initiatives such as the Green Jobs Initiative (UNEP 2008). These initiatives highlight the role of green jobs in reducing energy consumption, minimising pollution, and supporting sustainable development. The ongoing debate revolves around defining green jobs, measuring their impact, and understanding their contribution to the broader transition towards a circular economy (Vona et al. 2019). In light of the above theoretical frameworks and practical considerations, the following hypothesis is articulated:

H5.

International trade activities have a positive impact on the creation of green jobs.

This hypothesis evaluates how internationalisation drives the growth of green jobs, contributing to sustainable development and supporting the transition towards more eco-friendly industry practices.

While H1 and H2 correspond to direct effects due to their focus on the immediate impact of international trade characteristics (i.e., elasticity of substitution and contingency measures) on employment, H3 and H4 correspond to indirect effects since their concern relies on the influence of firm-specific characteristics (i.e., juridical form and location) on international trade activities (i.e., exports and imports), which, in turn, affect the employment dynamics of PTAI. Finally, H5 identifies whether international trade activities foster a differentiated impact between employment defined in a broad sense vis-à-vis the availability of green jobs.

2.2. Mathematical Formalisation: Transitioning from the Theory into the Empirical Analysis

While most academic studies only select the set of inputs to be used in the empirical analysis by relying on postulates from existing studies, this research complements such a view by providing a mathematical foundation to justify the deterministic component of the multiple linear regression model to be employed. A Cobb–Douglas production function is assumed to represent characteristics of the supply side, which implies that the real output of firm in period is given by

where stands for the real output, represents the capital stock, represents labour units, is the elasticity of output with respect to capital, β is the elasticity of output with respect to labour, and represents the technological progress or the improvement in total factor productivity, which occurs at the rate representative of Newton’s giant shoulders effect. Economically speaking, this effect suggests that the more past inventions help to boost the rate of current inventions, the faster the growth rate will be. From a theoretical point of view, profit maximisation requires labour (capital) being set at the level where marginal revenue is equal to wage (marginal cost ), respectively. Knowing that, each firm yields

the marginal revenue of capital and labour, respectively, corresponds to

Given the concern related to the effects on the labour factor, can be re-expressed as a function of , and

such that

Substituting the previous expression in Equation (1) yields

Taking the natural logarithm of this expression, one obtains

where , and with , , and . Similar to Greenaway et al. (1999), the technical efficiency of production processes is assumed to increase over time. Additionally, the rate of technology adoption and increases in x-efficiency are assumed to be correlated with changes in international trade. However, while Greenaway et al. (1999) assume a Cobb–Douglas production function to represent the variation of parameter A for a given exogenous change in the magnitude of imports and exports, this study extends their framework by considering that parameter A also varies based on substitutability patterns between imports and exports. This refinement, which requires one to rely on a variable elasticity of substitution (VES) production function, ensures the necessary flexibility to clarify how the evolution of PTAI based on international trade affects its technological progress because the representative parameter of the elasticity of substitution between imports and exports turns out to be affected by the size of both inputs. Historically, the VES production function was firstly introduced in Hicks (1932). Thenceforth, Vinod (1972, 1976) adopted it to analyse the telecommunications industry, and, more recently, Ramcharran (2001) and Kouliavtsev et al. (2007) have used it to formalise the textile industry’s strategic behaviour. Formally, one hypothesises that the technological progress varies in the following manner

where captures the firm-specific time trend, corresponds to imports, corresponds to exports, captures the sensitivity of technological progress with respect to the time trend, is the elasticity of technological progress with respect to imports, x is the elasticity of technological progress with respect to exports and captures the sensitivity of technological progress with respect to the interaction term that represents the international trade dynamics. This specification assumes constant technology across firms and over time, despite the fact that the elasticity of substitution is allowed to vary in both dimensions. Although this assumption may not be completely innocuous because the universe of PTAI companies is expected to be heterogeneous, the time period under analysis is relatively short. As such, the key property that the previous function brings seems to constitute a sufficient condition to allow the capture of international trade patterns on the formation of technological progress at the firm level. The marginal rate of technical substitution (MRTS) measures the rate at which both factors can be interchanged, while holding parameter constant. For each firm, MRTS is formally equal to the ratio of marginal revenue products

Based on Vinod (1972), the scale elasticity corresponds to the sum of all input elasticities

The elasticity of substitution between and at the technological progress level faced by firm is given by

which depends on both and levels. Since the expression of parameter in natural log form is given by

the substitution of the previous expression in Equation (2) allows one to obtain the estimable static panel data model

with , and . The remaining parameters are given as follows: , , , , and . In terms of a panel regression model equation, the previous expression becomes

where:

- is the total employment of firm in period ;

- is a firm-specific intercept term;

- is a period-specific trend factor;

- is the average real wage of firm in period , with marginal cost normalised to 1;

- is a measure of real output (e.g., gross value added (GVA), business volume, sales) representative of firm in period ;

- is the import volume of firm in period ;

- is the export volume of firm in period ;

- is the disturbance term, which may include a random component in addition to a white noise.

Two caveats are worth detailing. First, Equation (3) can be used to accommodate different regression models by applying appropriate restrictions. For instance, introducing the constraint , = 0 , and assuming that is white noise implies the definition of a pooled regression, which can be estimated by ordinary least squares (OLS). Similar reasoning is applied to the inference of two-way fixed effects or random effects models. Second, Equation (3) can be extended to a log–log regression model grounded by a dynamic panel data approach aimed at quantifying the impact of time-lagged covariates on the target. The need of including a dynamic component (e.g., lagged dependent variable) into the regression model is theoretically justified by the fact that adjustment costs in the level of employment frequently require short-term deviations from the steady-state equilibrium. Moreover, since the employment measure is the aggregation of workers potentially characterised by holding distinct adjustment costs, additional lags may be necessary to control for heterogeneity (i.e., unit-specific effects) (Nickell 1986). A longer lag structure may also be needed if serially correlated shocks are present in the data. Furthermore, lagged dependent variables may be introduced when bargaining considerations are internalised (e.g., expectations on future wages and output levels). Purely specifying dynamics in terms of lags applied to the dependent variable implicitly imposes a common evolution for employment. This restriction may be relaxed by introducing a lag structure in some regressors of interest (i.e., exports and imports).

3. Methods

3.1. Data

The dataset was downloaded from the Sistema de Análisis de Balancos Ibéricos (SABI). After pre-processing raw data, the final sample consists of 5557 registered companies, whose operational activity covers the 18 four-digit sectors of the PTAI over the period between 2010 and 2017. Firm-level data include observations on the following:

- The number of workers (L).

- Average wage (W).

- Import volume (M).

- Export volume (X).

- GVA (Q).

The development of several robustness checks required the collection of information on the following:

- Juridical form (JF).

- Own capital founded or not by family funds (Fam).

- Maturity (i.e., years since market entry) of firms (AGE).

- The segmentation of import and/or export volumes by origin and/or destination market (i.e., outside the EU territory vs. inside the EU territory).

Furthermore, using a dummy variable, PTAI companies were agglomerated based on the geographical place of the respective cluster in order to distinguish between clusters located in the north of the country and clusters located in any other region of the country. Additional controls were included in the deterministic component of the regression model when unsupervised machine learning is used to study the formation of green capital and green employment in the PTAI, whose details are clarified in Section 3.2.

3.1.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for the period 2010–2017 after all the selected variables measured in nominal terms being deflated through the appropriate price index, but before introducing a logarithmic form.

Table 1.

Summary statistics.

On average, a PTAI company has 24 workers and €326 corresponds to the average net wage paid to the representative worker. On average, the import (export) value of PTAI companies is equal to €678 (221) thousand, respectively. PTAI companies provide, on average, a contribution of €286 thousand to the domestic economic activity of Portugal. Overall, PTAI’s business is characterised by a high degree of heterogeneity due to the considerably high standard deviation that transversely affects the selected explanatory variables.

3.1.2. Preliminary Statistical Tests to Evaluate the Satisfaction of Classical Hypotheses

Recall that deterministic component of the multiple linear regression model is based on our extension of the mathematical model seminally proposed by Greenaway et al. (1999). To reinforce this theoretical ground, we analyse beforehand:

- Multicollinearity through the correlation matrix and variance inflation factor (VIF) statistics and, as confirmed by the panoply of results exposed in Table 2, conclude that all explanatory variables should be used to explain the target.

Table 2. Correlation matrix and VIF statistics.

Table 2. Correlation matrix and VIF statistics. - Specification through the Ramsey RESET test3 and, from the test statistic whose outcome is , conclude that a linear model cannot properly explain the target due to the rejection of the null hypothesis; as such, the introduction of logarithmic form in the target and explanatory variables, as specified in Equation (3), is the appropriate option for this case study.

- Homoscedasticity, whose Breusch–Pagan test detects the presence of heteroscedasticity (, p-value = 0.000), thus creating the need to apply the Huber–White procedure to restore the classical hypothesis of homoscedasticity.

- The absence of autocorrelation and the exogeneity of regressors were also inspected.

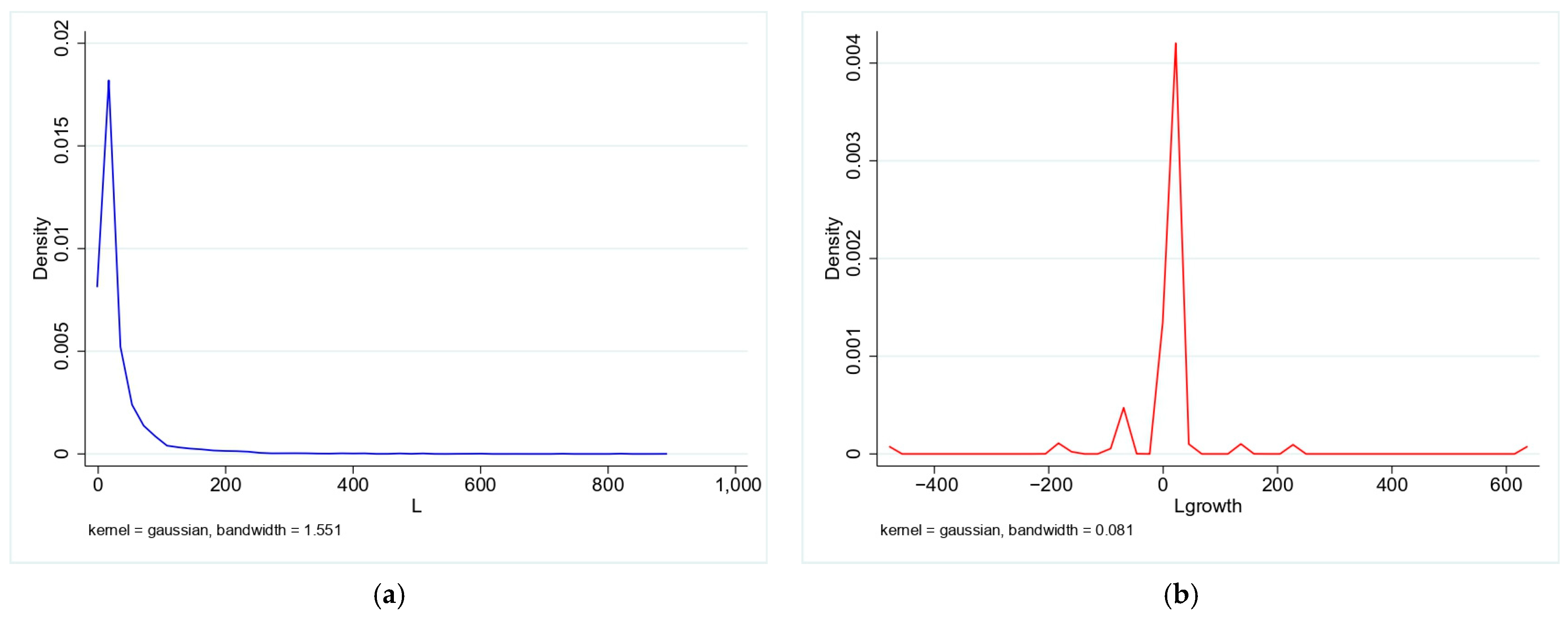

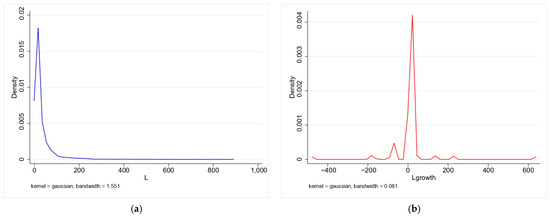

In the literature focused on assessing employment dynamics and trends, studies can be observed that analyse either developed countries (Bottazzi and Secchi 2006; Bottazzi et al. 2011) or developing countries (Yu et al. 2015; Mathew 2017). Moreover, it is transversally accepted that the distribution of employment level and employment growth rate is heavy tailed. Figure 3 allows for inferring that both distributions exhibit this property in the PTAI. The level of employment is also right-skewed, thereby reflecting a positive skewness since more than 80% of PTAI companies have less than 10 workers. Similar to past studies, the majority (a small number) of PTAI companies contain a low (high) number of employees, which means that the business tissue is predominantly characterised by the presence of SMEs, respectively.

Figure 3.

Kernel density estimation: (a) level of employment in the PTAI (2010–2016); (b) growth rate of employment in the PTAI (2010–2016).

3.2. Empirical Strategy to Analyse Employment Defined in a Broad Sense

The empirical assessment is focused on a panel data analysis, which follows five main steps summarised as follows:

We start by considering three static panel data models—pooled OLS (POLS), fixed effects, and random effects—to evaluate the behaviour of the dependent variable based on the deterministic component described by Equation (3). Under the POLS, explanatory variables are assumed to have a common impact across firms. This may be questionable because, for instance, each PTAI company may exhibit specific characteristics. Firm-specific fixed effects allow for unaccounted differences between firms, which are constant over time. Therefore, taking the first difference transformation of Equation (3) may be necessary in order to transform firm-specific fixed effects and accommodate time-specific fixed effects. However, Baltagi (2008) warns that the lagged dependent variable can be serially correlated with unobserved fixed effects in the residuals, which causes bias and inconsistency in the estimated coefficient of the lagged target. To overcome this debility, Anderson and Hsiao (1981) suggest complementing the first difference transformation of Equation (3) with the use of a lagged dependent variable as instrument to ensure consistent estimates of parameters.

The second task consists of applying two different types of dynamic panel data models aimed at incorporating dynamic adjustments of the dependent variable over time. On this domain, the generalised method of moments (GMM) technique of Arellano and Bond (1991) and Blundell and Bond (1998) was adopted in this study. Exploiting it allows for controlling for the endogeneity of the lagged dependent variable in cases where there is correlation between explanatory variables and disturbance terms. Surpassing the endogeneity problem is particularly relevant because, for instance, exports and imports are likely to influence GVA which, in turn, is likely to have a significant effect on employment, thereby reflecting that reverse causality can exist, at least from a theoretical perspective. To mitigate this source of concern, Arellano and Bond (1991) and Blundell and Bond (1998) propose the use of instrumental variables to infer moment conditions by means of applying a difference GMM model. The basic idea is to eliminate individual fixed effects by proceeding with the first difference in the regression equation in first place. Then, the lagged dependent variable is regarded as the corresponding instrumental variable of endogenous variables in the difference equation, which allows for exploiting the orthogonality conditions between the dependent variable and the disturbance term. Bond et al. (2001) confirm that the difference GMM model may suffer from the weak instruments problem in finite samples, being thus characterised by a poor estimation precision since the endogeneity problem can still persist. A solution to this concern is proposed by Arellano and Bover (1995), which consists of including additional moment restrictions through a system GMM model where a system of two equations is defined: an equation in differences instrumented by lagged levels and an equation in levels instrumented by lagged differences. This method not only introduces more moment conditions to increase the efficiency of instruments, but it also transforms existing instruments to make them uncorrelated with fixed effects. In addition to reducing the imprecision and potential bias related to the difference GMM estimator, the system GMM estimator is able to correct the unobserved heterogeneity problem, omitted variable bias and measurement errors (Blundell and Bond 1998). Additionally, Roodman (2009) clarifies that a system GMM estimator is efficient in the sense that it expands the instrument set as the panel progresses and the number of potential lags increases. When resorting to dynamic panel data models, the lagged dependent variable is used as the internal or endogenous instrument, while dummy variables representing years 2010 and 2013 are used as external or exogenous instruments to dissuade concerns related to endogeneity.4 Furthermore, it is important to highlight that the number of instruments must be lower than the number of units or groups of the panel in GMM. Otherwise, estimates are considered invalid (Roodman 2009).

The third step consists of following the rule-of-thumb proposed in Bond et al. (2001) to choose between the difference GMM model and the system GMM model. Initially, the dynamic model is estimated through POLS and fixed effects. The coefficient associated with the lagged dependent variable under the POLS (fixed effects) serves as the upper (lower) bound of reference, respectively. Thenceforth, the dynamic model is estimated through difference GMM. If the coefficient associated with the lagged dependent variable is close or below the fixed effects estimate, then the GMM estimate is downward-biased because of weak instrumentation, so that the system GMM estimator should be adopted.

The fourth action consists of executing a test to check for the presence of autocorrelation and a test to check the validity of external instruments. On the one hand, the system GMM estimator is said to be robust to heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation as long as the differenced equation is free of second- or higher-order serial correlation. The respective validity is based on the calculation of test statistics, which are normally distributed under the null hypothesis of no serial correlation. The key idea is that the number of instrumental variables must not exceed the number of endogenous variables to ensure that moment conditions are not overly constrained. Thereafter, for lagged endogenous variables and weak exogenous variables to be valid as instruments, it is necessary that the transient disturbances in the base model are free of autocorrelation (Blundell and Bond 1998). To satisfy this purpose, we consider the Arellano–Bond test for first-order (i.e., AR(1)) and second-order (i.e., AR(2)) serial correlation in first-differenced residuals (Arellano and Bond 1991). Because first differences in independently and identically distributed (iid), idiosyncratic errors will be serially correlated, rejecting the null hypothesis of no serial correlation in the first differenced error at order one does not imply that the model is incorrectly specified. However, rejecting the null hypothesis that the differenced error term is not second- or higher-order serially correlated implies that the moment conditions are not valid. Contrarily, failure to reject the null hypothesis of no second-order serial correlation implies that the original error term is serially uncorrelated, and the moment conditions are correctly specified. As a result, we restrict the focus on analysing the observed p-value associated with the AR(2) statistic. If the AR(2) statistic test is not significant, such that the observed p-value is above the critical p-value of 0.05, then the null hypothesis cannot be rejected, and, consequently, the absence of second-order serial correlation cannot be rejected.

On the other hand, the validity of moment conditions can be tested by Sargan and Hansen—in case of heteroscedasticity—tests, whose null hypothesis is that instruments are overall exogenous and, thus, valid. The Sargan test statistic has a good behaviour only when disturbances are homoscedastic (Iqbal and Daly 2014). Additionally, the Sargan test may have a low power to reject the null hypothesis; instruments may be only valid when the sample size is small and tend to over-reject the null hypothesis of serial uncorrelated errors in case of one-step GMM estimations (Bowsher 2002). Based on the debilities associated with the Sargan test and knowing that the Hansen test is the most widely adopted statistical test in econometrics practical work (Chen and Sun 2014), this is the one considered to assess the validity of instruments. If the Hansen test is not significant such that the observed p-value is above the critical p-value of 0.05, then the null hypothesis cannot be rejected, and thus, the exogeneity of instruments cannot be rejected.

Recent studies focused on econometric aspects recognise that combining lagged instrumental variables with the GMM technique may not be adequate, given that, under this circumstance, researchers are simultaneously trying to control for unobserved heterogeneity, while, at the same time, lagged and endogenous regressors are included, which can cause estimation problems (e.g., lack of significance and loss of statistical validity for inference), particularly when the panel is either weakly or strongly balanced due to missing data. Moreover, criticism can emerge with respect to the presence of omitted variable bias. To dissuade these sources of concern, Moral-Benito et al. (2019) propose an alternative method that consists of estimating coefficients through a linear dynamic panel data model that resorts to a quasi-maximum likelihood (QML) estimator under a structural-equation-modelling (SEM) approach. As detailed in Appendix A, the choice of random effects for the linear dynamic QML–SEM model is justified by the set of arguments exposed in Bell and Jones (2015). Consequently, the fifth step introduces this improvement based on the rationale that it is substantially more efficient than the GMM technique when the normality assumption is satisfied, mitigates selectivity problems, and suffers less from finite sample biases (Williams et al. 2018).

3.3. Empirical Strategy and Measurement Tools to Analyse the Penetration of Green Employment

Regarding the extension that allows for distinguishing between employment defined in a broad sense and green employment, one should start by emphasising that the empirical identification of the penetration of green employment in any industry is challenging because of five main reasons, which are summarised as follows:

- It is not easy to define what a green job is because of the ample spectrum of actions devoted to environmental concerns and sustainability.

- Empirical evidence on green employment is still limited in terms of timespan and scope due to data constraints.

- Addressing environmental challenges entails adapting the skill base and, thus, the composition of the labour force, which suggests that the definition of green employment is expected to be mutable due to its dynamic nature.

- Uncoordinated data collection by national statistical offices frequently fosters different statistical accounts even within a given national jurisdiction.

- The literature presents different methods to define green employment, namely:

- A strand of studies measures green jobs through the definition of a dichotomous variable, thus disregarding the continuous nature of green activities.

- Some studies approximate the share of green employment with the share of green capital over total production, thus inferring green jobs indirectly from industry and/or product characteristics; therefore, this approach does not capture the effective engagement of workers with activities that use green technologies and environmentally efficient production processes.

- Other studies quantify workers’ dedication to green activities by computing the ratio between green occupational tasks and the total number of occupational tasks, thus disregarding that green occupational tasks exist because firms previously adopt technologies that require different skills (also known as green skills), regardless of whether the type of occupation is permanent or not.

Given these sources of ambiguity, a robust ensemble approach is used to identify and measure the penetration of green employment in the PTAI, which is summarised as follows:

- In a first stage, an unsupervised machine-learning model—principal component analysis (PCA)—is applied to endogenously determine latent dimensions capable of representing green capital and green employment; and

- In a second stage, a two-step procedure is considered to distinguish between the following:

- The first step—capital-based—discrete choice (i.e., yes or no probabilistic decision with respect to the endowment of green technologies and environmentally efficient production processes by PTAI companies); and

- The second step—labour-based—continuous choice (i.e., knowing that PTAI companies have previously implemented green technologies and environmentally efficient production processes, it consists of assessing determinants of green employment by applying three distinct estimation methods: OLS estimation, Cragg’s model, and Heckman’s selection model).

This robust ensemble approach reduces the estimation bias and reinforces the notion that all occupations are potentially interconnected with green activities, at least up to a certain extent, since these are contingent on the ex-ante adoption of green technologies and environmentally efficient production processes at the firm level. Furthermore, aligning with contemporary conceptual frameworks (Salem et al. 2023; Asad et al. 2024), an SEM approach is employed to analyse the role of two mediators in the relationship between international trade and green employment:

- The accommodation of green technologies and environmentally friendly processes by PTAI companies; and

- The maturity of PTAI companies.

In doing so, a novel contribution is provided to the literature, which consists of giving a dynamic, though realistic, notion of the penetration of green jobs in PTAI companies.

4. Results

4.1. Benchmark Analysis: Impact of International Trade on Employment Defined in a Broad Sense

4.1.1. Coefficients

Table 3 presents benchmark outcomes, which are subject to interpretation and discussion. Two different models are empirically tested:

Table 3.

Estimated coefficients of the QML–SEM regression model with random effects.

- Model (A) disregards the interaction term between imports and exports.

- Model (B) incorporates the strategic interaction between exports and imports.

As described in Equation (3), this means that model (B) captures the endogenous mechanism whereby PTAI companies initially benefit from the appropriation of knowledge spillovers given their engagement in international trade activities. Thenceforth, the appropriated know-how affects the internal technological progress of PTAI companies, which turns out to influence the employment dynamics. As such, international trade activities can be interpreted as having a purely direct and isolated effect on the dependent variable only in the case of model (A).

Let us start by focusing on the results of model (A). In terms of statistical significance, all estimated coefficients are significant at the 1% level. In terms of sign, wages, exports, and imports affect employment negatively. While the wage effect is expected, a similar effect is not applied to international trade activities, where the results indicate that a higher degree of openness to international markets has a permanent, negative, and significant effect on employment in the PTAI. Although several reasons justify the efficiency gain caused by the combination of increasing exports with decreasing employment, it should be emphasised the gradual replacement of labour-intensive goods by capital goods, which are characterised by technological refinements (e.g., at the level of machinery and equipment) throughout the entire value chain.

The reduction in employment for increasing import volumes can be justified by the increase in outsourcing practices in traditional activities of the upstream market (e.g., input purchases), which promotes external dependence from developing countries at the wholesale market level. Although increasing the dependence on foreign suppliers implies that PTAI companies are more likely to face input price volatility, it also exacerbates a reduction in domestic labour needs.

The previous outcomes are counterbalanced by the permanent, positive, and significant effect of GVA on employment. This result suggests that the willingness to hire remains high when PTAI companies deal with favourable economic contexts (e.g., increasing consumer purchasing power). Moreover, the lagged dependent variable affects employment positively, which suggests the persistence of a positive autocorrelation. In terms of the magnitude of effects, all covariates have an inelastic relation with the dependent variable because estimated coefficients are below the unit value. In fact, most estimates are close to zero, which reflects the high degree of rigidity that characterises the PTAI’s labour market. The strongest elasticity is observed in GVA, where a 1% increase implies a 0.66% employment growth in the short-run, ceteris paribus. Although the value increases to 0.954, it remains inelastic in the long-run. We also emphasize that the sensitivity of employment in relation to exports is weaker than its sensitivity in relation to imports ( −0.030 −0.024). Lastly, results demonstrate that all impacts on the dependent variable are unambiguously stronger in the long-run.

Let us now reflect on the results of model (B). One can observe that the estimated coefficient associated with the covariate XM is permanently negative and significantly affects the dependent variable, which implies that the enhancement of the internal technological progress boosted by the intensification of export and import volumes does not contribute to increase the level of domestic employment. Results also reveal that the sign of X coefficient is positive, which validates the argument that exports promote domestic employment presented in Greenaway et al. (1999). However, the estimated coefficient does not exhibit statistical significance, as does the estimated coefficient associated with imports. In fact, both elasticities are negative, meaning that they affect firms’ output negatively, which discourages job creation. Both have an inelastic nature and a redundant increase of 1 percentage point (p.p.) in terms of magnitude once adjusting for the long-run equilibrium. Despite the negative impact of international trade activities on employment, benefits from the absorptive capacity of external knowledge can be particularly relevant for the economic growth of a small open economy like Portugal. Knowing that model (B) captures the effectiveness of the absorptive capacity of PTAI companies, it brings the technical advantage of avoiding the overestimation of the capital elasticity (i.e., 0.063 in model A vs. 0.057 in model B). As expected, similar is not applied to the labour factor due to the long-term adjustment mechanism previously detailed.

4.1.2. Scale and Substitution Elasticities

To obtain estimates on the theoretical constructs clarified in Section 2.1, we combine the estimated coefficients of model (B) with the time series of , , and . Regarding the marginal productivity on imports (MPM) and the marginal productivity on exports (MPX), we briefly report that PTAI companies tend to exhibit a positive and increasing value over time in the 2010–2017 period, which is consistent with reports from other manufacturing industries (ATP 2018).

While a few firms experience adverse productivity shocks on exports between 2010 and 2011, a steady growth is observed in the MPX for most firms from 2012 to 2014. In general, the 2015–2017 period is characterised by the same upward trend, but with the provision that some major jumps are identified. Therefore, the best performance of PTAI companies in terms of exports has been achieved in recent years. PTAI companies are also characterised by upward adjustments in imports. Once confronting marginal productivities, results show that the MPM surpasses the MPX in most PTAI companies during 2010–2017.

Short-run- and long-run-scale elasticities are constructed as the sum of marginal elasticities of both international trade activities plus the adjustment caused by the interaction term between imports and exports. The scale elasticity measures the percentage variation between imports and exports caused by the distortion in transacted volumes in favour (disfavour) of exports (imports), which means that a higher (lower)-scale elasticity indicates a stronger substitutability pattern of imports by exports caused by the increasing (decreasing) variation in exports relatively to imports, respectively. In other words, a stronger (weaker) relative importance of exports is not verified due to additional firms changing their behavioural nature from being import-dependent to become export promoter but merely due to the higher (lower) transacted volume of exports relative to imports, respectively. Overall, scale elasticities are relatively stable across PTAI companies. Average values are bounded between −0.015 and 0.099 in the 2010–2017 period, which reflects the accommodation of all types of possibilities: decreasing, constant, and increasing returns. At the individual level, a considerable number of PTAI companies faced substantial positive changes in the scale elasticity over time, thereby reflecting that PTAI companies may actually export more, but their trading profile has not changed significantly. Increases in the scale elasticity were identified in almost 40% of observations, despite some being relatively modest. A few firms felt a modest decline in the scale elasticity from 2010 to 2011, which turned out to be readjusted in subsequent years, particularly in the biennium 2015–2016.

In terms of the elasticity of substitution of imports by exports, Table 4 shows that the global mean value for the PTAI is equal to 0.605, and annual mean values are between 0.5 and 0.7. Therefore, results are consistent with the theoretical expectation of negatively sloped isoquants () as well as with the empirical regularity of finding substitution elasticities within the unit interval. The interpretation of the global mean value reveals that a 1% increase in imports implies a 0.6% increase in exports, so that we cannot corroborate that the good performance of PTAI companies is attributed to business models oriented to exports. Instead, the inelastic nature suggests that the good performance of PTAI companies is predominantly caused by the reformulation of their cost structure, mainly in the wholesale market, which is currently more flexible than in any other historical period. Nevertheless, pronounced differences are found in the variation and magnitude of the elasticity of substitution between imports and exports across PTAI companies: approximately 55% exhibit a rise in , while near 48% define a modest increase (i.e., ). The complementary fraction suggests that fewer firms are characterised by a decline in the elasticity of substitution of imports by exports, with only 8% of the sample corresponding to a strong drop. The analysis of the magnitude of effects indicates that, on average, declines were smaller than increments, which is consistent with the effort to promote a substitutability.

Table 4.

Estimated scale and substitution elasticities of imports by exports in the PTAI.

Table 4 also shows that the annual mean value of the elasticity of substitution between imports and exports follows a non-monotone configuration since it increased between 2010 and 2014, decreased from 2014 to 2015, but increased again from 2015 to 2017. The positive trend reflects the reduction in external dependence and enhancement of the external penetration, which suggests that PTAI companies are moving to a business logic characterised by increasing exports. As such, empirical results demonstrate that H1 is rejected in the PTAI’s context: the elasticity of substitution of imports by exports has a negative effect on employment.

In what follows, four robustness checks are applied to model (A). We disregard the interaction term between exports and imports since this refinement is only mandatory to find evidence about H1. Moreover, the qualitative nature of results remains unchanged regardless of whether the covariate XM is included or not.

4.1.3. Geographical Restrictions on International Trade

At first glance, it may seem paradoxical to analyse this particularity in the context of a globalised world. However, recent experiences have demonstrated that geographical restrictions on international trade can be imposed due to some exogenous shock (e.g., COVID-19, Brexit, Russia–Ukraine conflict). Two cases are covered by this refinement:

- The circumstance where the Portuguese international trade is restricted to regions belonging to the European territory (i.e., the analogous situation to that observed under the COVID-19 pandemic).

- The circumstance where the Portuguese international trade is restricted to regions outside the European territory (i.e., the analogous situation to that observed under the Brexit).

Estimated coefficients are presented in Table 5. Model (A) covers the first case, while model (B) covers the second case. Results in model (A) indicate that all explanatory variables are statistically significant. Moreover, all covariates remain with the same sign, relative to the benchmark analysis, thereby reflecting that the EU territory is the main destination market of PTAI companies. If the Portuguese international trade is restricted to regions inside the EU territory, then a negative impact on employment is expected to persist. Differently, results in model (B) indicate that all explanatory variables are statistically significant with the exception of exports to countries outside the EU. Although the positive sign of the estimate suggests that it is not necessarily true that the domestic employment is reduced, the absence of significance on the dependent variable undermines its statistical validity. The lack of significance suggests that additional efforts are needed to increase the reputation of PTAI companies in destination markets outside the EU.

Table 5.

Impact of international trade’s geographical restrictions on PTAI’s employment.

The validation of H2 requires to restrict the attention to model (A) and compare the estimated coefficients of X and M with those obtained in the benchmark analysis. If both coefficients have a stronger magnitude under this extension, then H2 is not rejected. However, results indicate failure to provide evidence in favour of a stronger negative impact of exports and imports on employment when the international trade is restricted to regions inside the EU territory. The estimated short-run coefficient of exports (−0.024, p-value < 0.01), the estimated long-run coefficient of exports (−0.035, p-value < 0.01), the estimated short-run coefficient of imports (−0.030, p-value < 0.01), and the estimated long-run coefficient of imports (−0.043, p-value < 0.01) under the benchmark analysis are all higher than the respective value obtained under this extension.

From an economic point of view, the rejection of H2 is justified by the diversification of supply sources and new destination markets of PTAI companies, which reduces their dependence on the EU market, particularly with respect to exports. As such, the effort of PTAI companies to conquer new destination markets implicitly has a detrimental impact on domestic employment.

4.1.4. Alternative Dependent Variable Measured in Relative Terms

Table 6 provides outcomes considering the employment growth rate (i.e., Lgrowth) as the dependent variable. Results show that covariates have a qualitatively similar influence on employment growth and employment level.

Table 6.

Robustness check: changing the type of dependent variable to a relative measure.

The main difference is that wage is no longer statistically significant and, thus, one cannot corroborate that wages and employment growth have a negative relation. Moreover, the magnitude of effects is unambiguously stronger when employment growth is the dependent variable since this is elastic to changes in exports, imports, and GVA. Finally, there is evidence of convergence in employment growth since the lagged dependent variable presents a negative and significant coefficient, whose magnitude is below the unit value.

4.1.5. Firm-Specific Control Variable: Own-Capital Realisation

While past contributions normally include age and size as firm-specific characteristics, our database allows for considering two original features: magnitude and source of own-capital realisation.

In model (A), we consider a dummy variable ‘JF’ that takes the value 1 if a Sociedade Anónima is established, which is a type of firm with limited responsibility that requires a minimum amount of €50,000 for constitution. Otherwise, the dummy variable takes value 0, which captures cases where either Sociedade por Quotas or Sociedade Unipessoal por Quotas is established.

In turn, model (B) follows Hodges and Link (2017) by considering a dummy variable ‘Fam’ that takes the value 1 if 100% of the own capital comes from family funds, while taking the value 0 otherwise.

Results in Table 7 confirm that the magnitude and source of own-capital realisation do not significantly affect the dependent variable, which suggests that employment fluctuations can occur regardless of the type of juridical form and funding source of PTAI companies. Thereafter, the database is segmented by the criterion used to define the dummy variable JF. This allows for isolating the effect of covariates strictly representative of Sociedades Anónimas on the dependent variable to confirm the validity of H3. Results in column C correspond to the case where only the covariates representing Sociedades Anónimas affect the dependent variable, while estimated coefficients of the alternative possibility (i.e., Sociedades por Quotas and Sociedades Unipessoais por Quotas) are presented in column D. The comparison between estimated coefficients of covariates X and M reveals that exports and imports of Sociedades Anónimas have the strongest impact on employment both in the short- and long-run horizon, which implies that H3 cannot be rejected. Another interesting finding is that wages only have a negative and significant effect on employment in the set of Sociedades por Quotas and Sociedades Unipessoais por Quotas. We also conclude that the positive impact of GVA on employment is stronger for Sociedades Anónimas, thereby meaning that these exhibit a higher propensity to hire.

Table 7.

Impact of the magnitude and source of own capital realisation on PTAI’s employment.

4.1.6. Geographical Control Variable: Location of PTAI Companies

Data reveal that the majority of PTAI companies is located in the north of Portugal. This is not surprising since two important clusters are located in this region, which has a strong tradition of developing textiles and apparel (ATP 2018). Bearing in mind the objective of validating H4, we construct a dummy variable ‘Cluster’ that takes value 1 if the firm is located in the north of Portugal, while taking value 0 otherwise. The empirical strategy consists of understanding whether the additive effect has a significant impact on employment and analyse whether the effect of covariates X and M on employment is stronger for the cluster of firms from the north of Portugal compared to clusters from other parts of the country.

Results in column A of Table 8 confirm that the physical location of PTAI companies does not have a significant effect on the dependent variable, which means that employment is transversely affected by international trade activities, wages, and GVA. Column B shows outcomes related to PTAI companies located in the north of Portugal, while estimated coefficients of the alternative case are presented in column C. The comparison between estimated coefficients of covariates X and M reveals that that exports and imports of PTAI companies located in the north of Portugal have the strongest impact on employment both in the short- and long-run horizon, thereby meaning that H4 cannot be rejected. Indeed, exports of firms from other parts of the country lack statistical significance on employment, and imports of firms are merely weakly significant.

Table 8.

Impact of the location of firms on PTAI’s employment.

We finalise this subsection by emphasising that the significant and negative sign of X and M estimated coefficients is resilient to the inclusion of several control variables. This suggests that the participation of PTAI companies in international markets has reduced employment opportunities defined in a broad sense. Given the strategic relevance of the Euro-Mediterranean region as the main wholesale supplier of the EU, these results reflect that the persistence of onshoring practices in Europe will be a challenging task in the future. Considering that these ensure positive returns to EU Member States, a transnational coordination seems mandatory to ensure the sustainability of TAI jobs in Europe (Clarke-Sather and Cobb 2019).

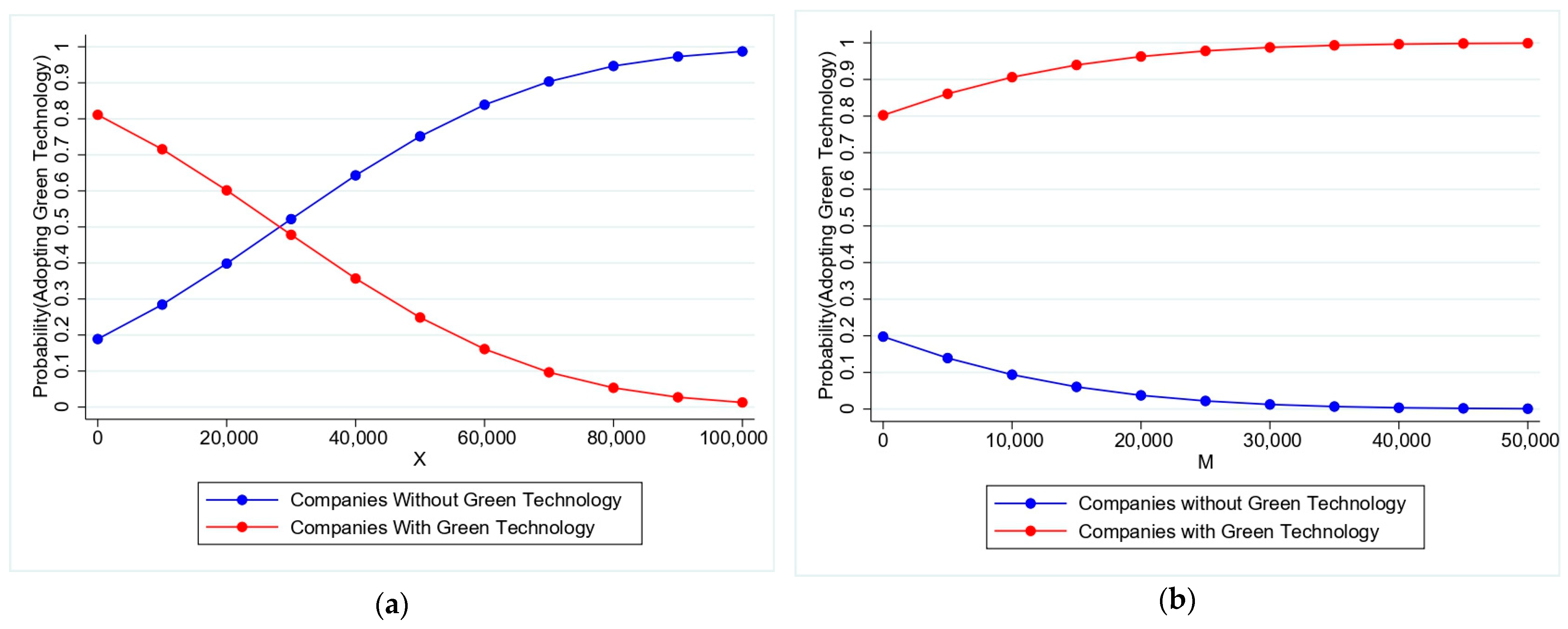

4.2. Extension: Analysing the Penetration of Green Employment in the PTAI

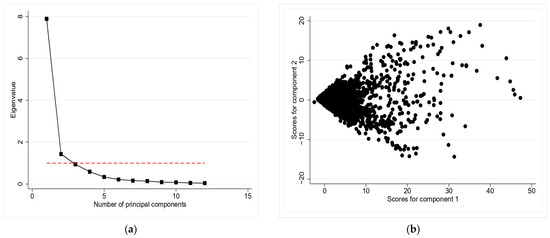

4.2.1. First Stage of the Ensemble Approach: Determination of Green Capital and Green Jobs

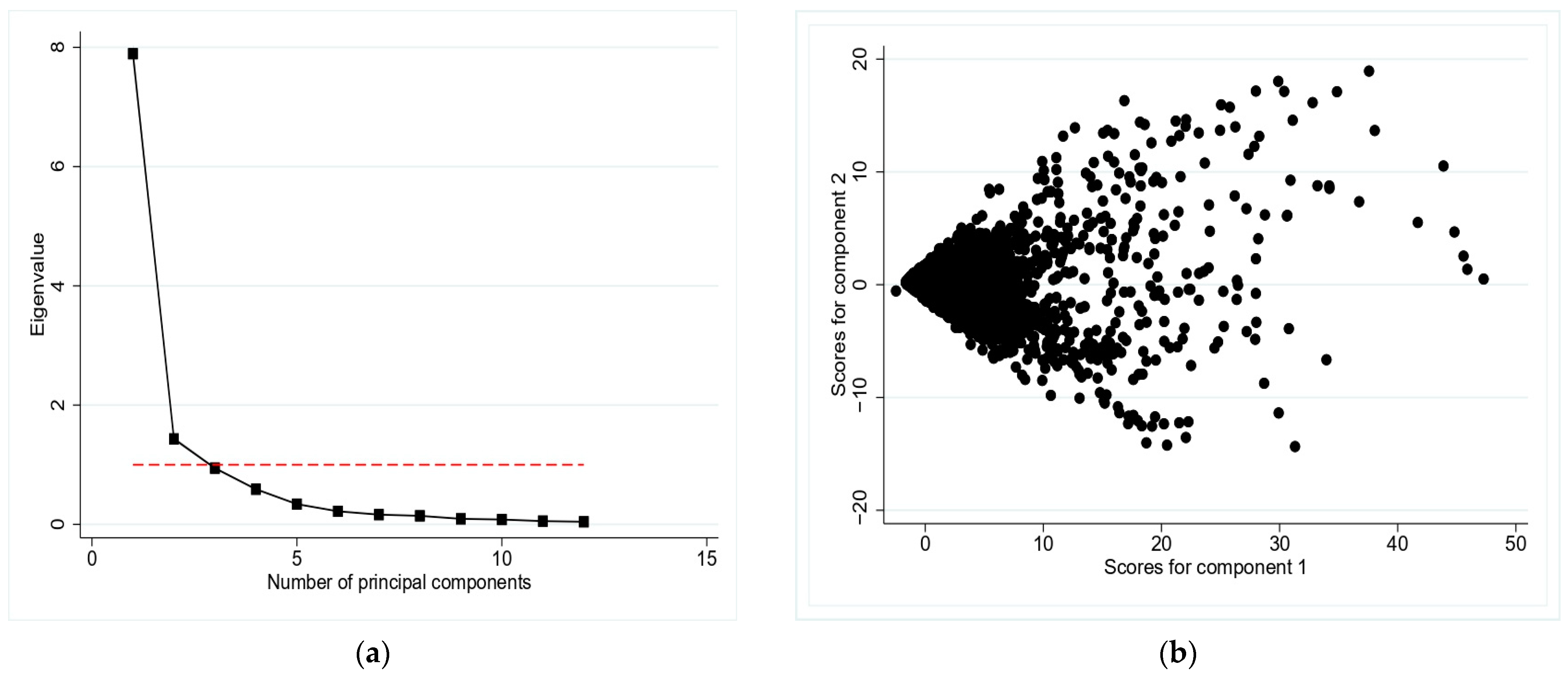

Following Bai and Ng (2003), we start by identifying relevant dimensions of the PTAI through a PCA. Because of using this unsupervised machine-learning method, covariates no longer have to take a logarithmic form. In addition to L, W, X, M, and Q, and knowing that the available data to perform this kind of analysis are scarce and limited, this extension considers the following:

- Labor factor lagged in time up to 5 periods (, , , , ).

- Maturity of firms (AGE).

- GVA of high and medium-high technologies (HMH).