Asymmetric Vacillation in the FMCG Industry: A Case Comparison of Procter & Gamble and Unilever

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Question

Organizational Vacillation Theory

3. Methodology

4. Result: Differences in Organizational Structures between Procter & Gamble and Unilever

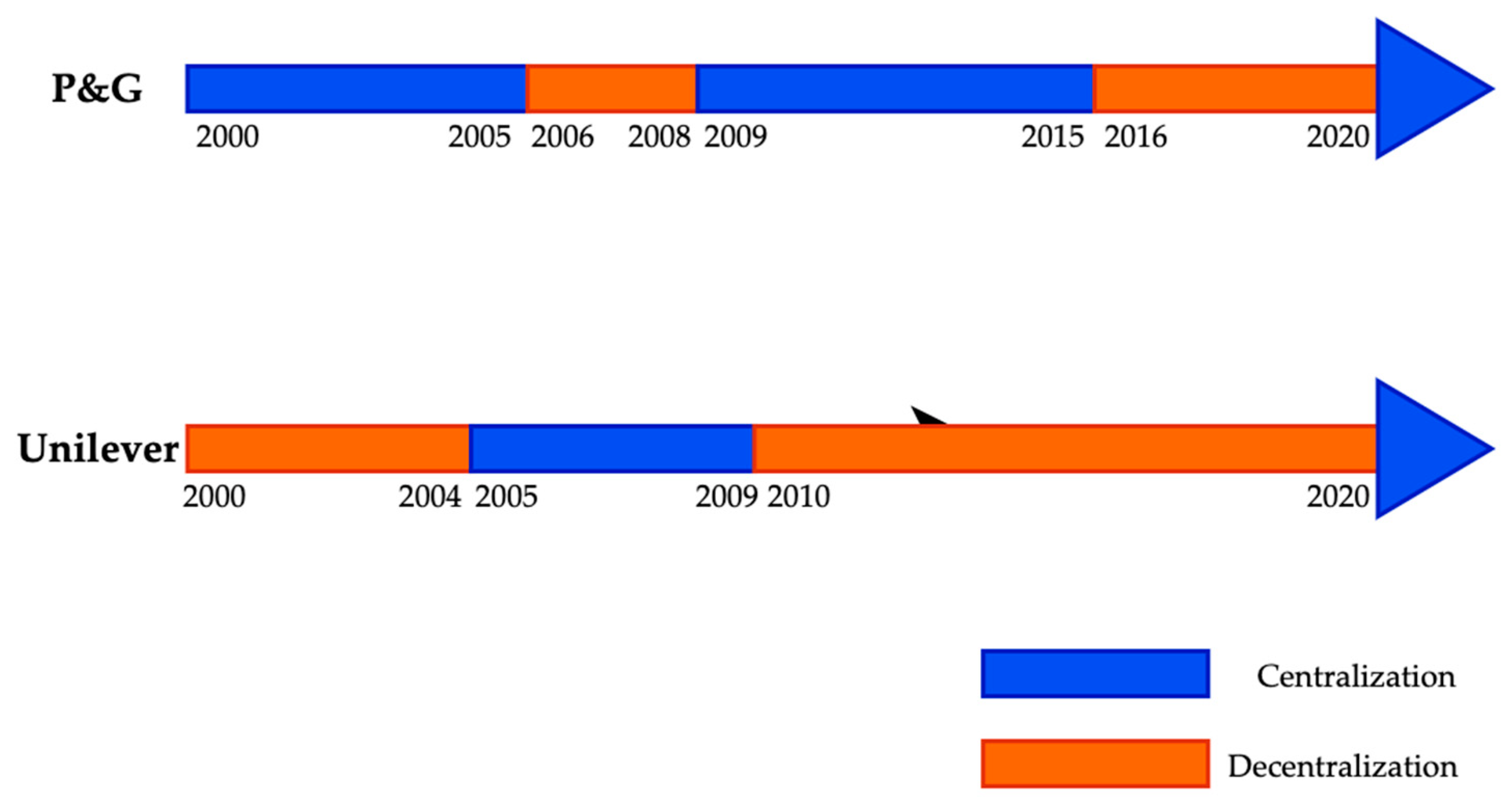

4.1. Procter & Gamble

4.1.1. The Business History of Procter & Gamble before 2000

4.1.2. Organizational Vacillation of Procter & Gamble after 2000

- Epoch 1: Centralization—The Organization 2005 Program (2000–2005)

- Epoch 2: Decentralization (2006–2008)

- Epoch 3: Centralization (2009–2015)

- Epoch 4: Decentralization (2016–2020)

4.2. Unilever

4.2.1. The Business History of Unilever before 2000

4.2.2. Organizational Vacillation of Unilever after 2000

- Epoch 1: Regionally decentralized structure begins (2000–2004)

- Epoch 2: A centralized Unilever: The One Unilever Program (2005–2009)

- Epoch 3: The move back to decentralization (2010–2020)

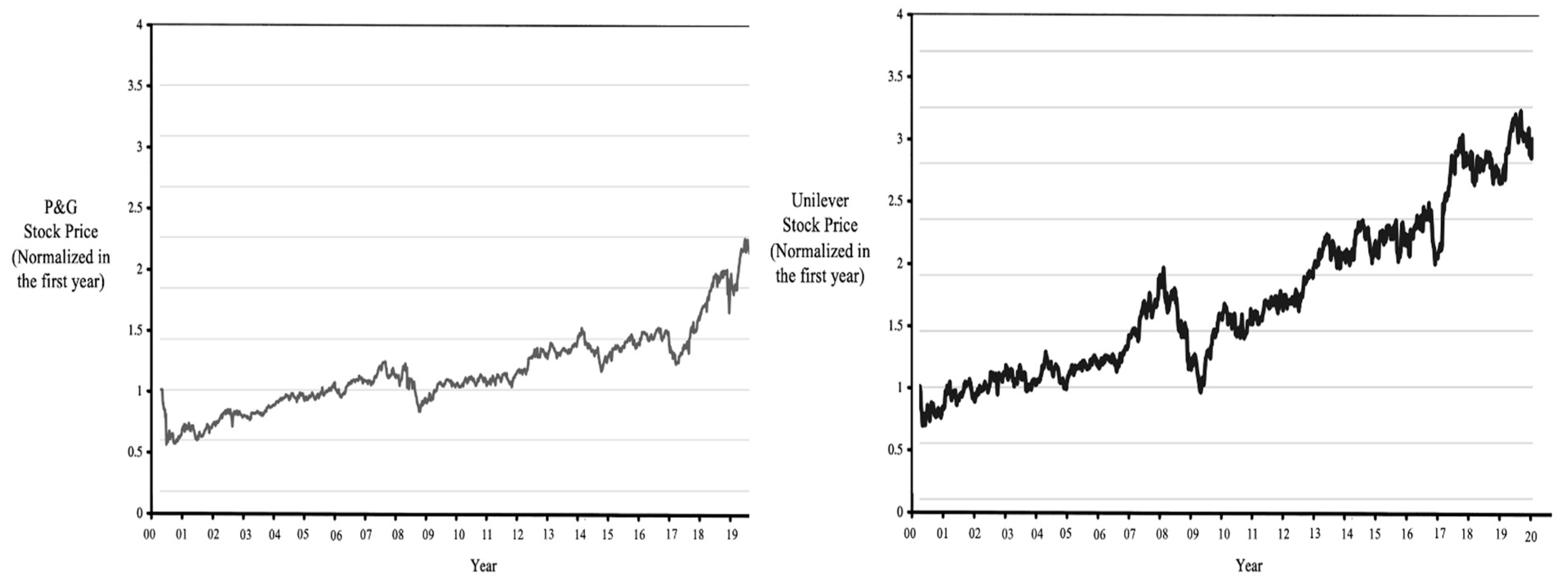

4.3. Comparing the Two Cases

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderson, Paul A. 1983. Decision making by objection and the Cuban missile crisis. Administrative Science Quarterly, 201–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriopoulos, Constantine, and Marianne W. Lewis. 2009. Exploitation-exploration tensions and organizational ambidexterity: Managing paradoxes of innovation. Organization Science 20: 696–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumgarden, Peter, Jackson Nickerson, and Todd R. Zenger. 2012. Sailing into the wind: Exploring the relationships among ambidexterity, vacillation, and organizational performance. Strategic Management Journal 33: 587–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Bruce, and Scott D. Anthony. 2011. How P&G Tripled Its Innovation Success Rate. Harvard Business Review. June. Available online: https://hbr.org/2011/06/how-pg-tripled-its-innovation-success-rate (accessed on 6 April 2021).

- Brown, Shona L., and Kathleen M. Eisenhardt. 1997. The art of continuous change: Linking complexity theory and time-paced evolution in relentlessly shifting organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly 42: 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandola, Sagar. 2016. Unilever Inmarko Case Study. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/24935262/Unilever_Inmarko_Case_Study (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Cummings, Stephen. 1995. Centralization and decentralization: The neverending story of separation and betrayal. Scandinavian Journal of Management 11: 103–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, Deborah, Robert G. Eccles, Nitin Nohria, and James D. Berkley. 1993. Beyond the Hype: Rediscovering the Essence of Management. Administrative Science Quarterly 38: 693–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dow, Douglas. 2000. A Note on Psychological Distance and Export Market Selection. Journal of International Marketing 8: 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesl, Martin. 2018. Why Unilever Is Right to Consolidate Its Headquarters in Rotterdam. The Conversation. Available online: https://theconversation.com/why-unilever-is-right-to-consolidate-its-headquarters-in-rotterdam-93454 (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- Gwynn, Simon. 2017. Unilever: We’re Launching More Local Innovations than Ever before. Campaign US. October 19. Available online: https://www.campgainlive.com/article/unilever-were-launching-local-innovations-ever/1447812 (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Hall, David J., and Maurice A. Saias. 1980. Strategy follows structure! Strategic Management Journal 1: 149–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, Michael T., M. Diane Burton, and James N. Baron. 1996. Inertia and Change in the Early Years: Employment Relations in Young, High Technology Firms. Industrial and Corporate Change 5: 503–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutzschenreuter, Thomas, Ingo Kleindienst, Florian Groene, and Alain Verbeke. 2014. Corporate strategic responses to foreign entry: Insights from prospect theory. The Multinational Business Review 22: 294–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Geoffrey. 2002. Merchants to Multinationals: British Trading Companies in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Oxford: OUP Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Junni, Paulina, Riikka M. Sarala, Vas Taras, and Shlomo Y. Tarba. 2013. Organizational ambidexterity and performance: A meta-analysis. Academy of Management Perspectives 27: 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Jingoo, Ribuga Kang, and Sang-Joon Kim. 2017. An empirical examination of vacillation theory. Strategic Management Journal 38: 1356–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassotaki, Olga. 2022. Review of organizational ambidexterity research. SAGE Open 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, Benjamin. 2000. Fisher-General Motors and the Nature of the Firm. The Journal of Law and Economics 43: 105–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luger, Johannes, Sebastian Raisch, and Markus Schimmer. 2018. Dynamic balancing of exploration and exploitation: The contingent benefits of ambidexterity. Organization Science 29: 449–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey & Co. 2020. Perspectives on Retail and Consumer Goods. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/retail/our%20insights/perspectives%20on%20retail%20and%20consumer%20goods%20number%208/perspectives-on-retail-and-consumer-goods_issue-8.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2021).

- Mintzberg, Henry. 1979. The Structuring of Organizations. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson, Jack A., and Todd R. Zenger. 2002. Being efficiently fickle: A dynamic theory of organizational choice. Organization Science 13: 547–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Chang Hoon, and Farok Contractor. 2014. A Regional Perspective on Multinational Expansion Strategies: Reconsidering the Three-stage Paradigm. British Journal of Management 25: S42–S59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okechukwu, Agburum, and Kenneth C. Adiele. 2019. Physic Distance and International Marketing Effectiveness of Fast-Moving Consumer Goods of Multinational Companies in Nigeria. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 8: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Omran, Hagar. 2018. P&G to more focus on expanding localizing its production. Daily News. July 4. Available online: https://www.dailynewsegypt.com/2018/07/04/pg-to-more-focus-on-expanding-localizing-its-production/ (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Oraman, Yasemin, M. Omer Azabagaoglu, and I. Hakki Inan. 2011. The firms’ survival and competition through global expansion: A case study from the food industry in FMCG sector. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 24: 188–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, Charles A., and Michael L. Tushman. 2011. Organizational ambidexterity in action: How managers explore and exploit. California Management Review 53: 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinfield, Lawrence T. 1986. A field evaluation of perspectives on organizational decision-making. Administrative Science Quarterly 31: 365–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piskorski, Mikolaj Jan, and Alessandro L. Spadini. 2007. Procter & Gamble: Organization 2005 (A). Harvard Business School Case 707-519, January 2007. (Revised October 2007). Massachusetts: Harvard Business School. [Google Scholar]

- Pitman, Simon. 2016. P&G Boss Targets Leaner and More Decentralized Business, in First Public Address. Cosmetics Design North America. February 22. Available online: https://www.cosmeticsdesign.com/Article/2016/02/22/P-G-boss-targets-leaner-and-more-decentralized-business-in-first-public-address (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Procter & Gamble. 1999. Procter & Gamble 1999 Annual Report. Available online: https://www.pginvestor.com/financial-reporting/annual-reports/ (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Procter & Gamble. 2000. Procter & Gamble 2000 Annual Report. Available online: https://www.pginvestor.com/financial-reporting/annual-reports/ (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Procter & Gamble. 2001. Procter & Gamble 2001 Annual Report. Available online: https://www.pginvestor.com/financial-reporting/annual-reports/ (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Procter & Gamble. 2003. Procter & Gamble 2003 Annual Report. Available online: https://www.pginvestor.com/financial-reporting/annual-reports/ (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Procter & Gamble. 2004. Procter & Gamble 2004 Annual Report. Available online: https://www.pginvestor.com/financial-reporting/annual-reports/ (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Procter & Gamble. 2006. Procter & Gamble 2006 Annual Report. Available online: https://www.pginvestor.com/financial-reporting/annual-reports/ (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Procter & Gamble. 2007. Procter & Gamble 2007 Annual Report. Available online: https://www.pginvestor.com/financial-reporting/annual-reports/ (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Procter & Gamble. 2010. Procter & Gamble 2010 Annual Report. Available online: https://www.pginvestor.com/financial-reporting/annual-reports/ (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Procter & Gamble. 2013. Procter & Gamble 2013 Annual Report. Available online: https://www.pginvestor.com/financial-reporting/annual-reports/ (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Procter & Gamble. 2015. Procter & Gamble 2015 Annual Report. Available online: https://www.pginvestor.com/financial-reporting/annual-reports/ (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Procter & Gamble. 2021. P&G History. February 12. Available online: https://us.pg.com/pg-history/ (accessed on 12 February 2021).

- Raisch, Sebastian, Julian Birkinshaw, Gilbert Probst, and Michael L. Tushman. 2009. Organizational ambidexterity: Balancing exploitation and exploration for sustained performance. Organization Science 20: 685–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Córdova, Carolina, Amanda J. Williamson, Julio A. Pertuze, and Gustavo Calvo. 2022. Why one strategy does not fit all: A systematic review on exploration-exploitation in different organizational archetypes. Review of Managerial Science 17: 2251–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solberg, Carl Arthur. 2002. The perennial issue of adapation or standardization of international marketing communication: Organizational contingencies and performance. Journal of International Marketing 10: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinchcombe, Arthur L. 1965. Social structure and organizations. In Handbook of Organizations. Edited by James March. Chicago: Rand McNally, pp. 142–93. [Google Scholar]

- Swamynathan, Yashaswini. 2016. P&G Needs to be More Agile, Says New CEO Taylor. February 19 U.S.. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-procter-gamble-ceo-idUKKCN0VR2FT (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Tweh, Bowdeya, and Alexander Coolidge. 2014. P&G to Create 800 Jobs at New Dayton-Area Warehouse. Cincinatti.com. May 16. Available online: https://www.cincinnati.com/story/money/2014/05/15/pg-dayton-distribution-center/9119273/ (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Unilever. 2003. Unilever 2003 Annual Report. Available online: https://www.unilever.com/investors/annual-report-and-accounts/archive-of-annual-report-and-accounts/ (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Unilever. 2005. Unilever 2005 Annual Report. Available online: https://www.unilever.com/investors/annual-report-and-accounts/archive-of-annual-report-and-accounts/ (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Zimmermann, Alexander, Sebastian Raisch, and Laura B. Cardinal. 2018. Managing Persistent Tensions on the Configurational Perspective on Ambidexterity. Journal of Management Studies 55: 739–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Centralization | Decentralization | |

|---|---|---|

| Annual report |

|

|

| Media |

|

|

| Major keywords |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kang, J.; Lee, S.; Choi, S. Asymmetric Vacillation in the FMCG Industry: A Case Comparison of Procter & Gamble and Unilever. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13080187

Kang J, Lee S, Choi S. Asymmetric Vacillation in the FMCG Industry: A Case Comparison of Procter & Gamble and Unilever. Administrative Sciences. 2023; 13(8):187. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13080187

Chicago/Turabian StyleKang, Jisoo, Seungyeon Lee, and Seungho Choi. 2023. "Asymmetric Vacillation in the FMCG Industry: A Case Comparison of Procter & Gamble and Unilever" Administrative Sciences 13, no. 8: 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13080187

APA StyleKang, J., Lee, S., & Choi, S. (2023). Asymmetric Vacillation in the FMCG Industry: A Case Comparison of Procter & Gamble and Unilever. Administrative Sciences, 13(8), 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13080187