Abstract

This research draws upon an institutional theory framework to explore the underlying factors that influence opportunity-driven and necessity-driven entrepreneurship. The objective is to analyze how the institutional environment either supports or impedes the establishment and expansion of ventures within the Thai hospitality industry. By examining the interplay between the country’s institutional determinants and entrepreneurial behaviors, the study contributes to the existing body of academic literature on entrepreneurship and institutional theory. Furthermore, education support is treated as a moderator in the relationship between the three determinants of the institutional environment theory: regulatory, cognitive, and normative dimensions, and opportunity-necessity-driven entrepreneurship activity. This study adopted a mixed methods approach. For the quantitative approach, national data were mainly collected from the GEM and IEF databases from 2015 to 2018 (n = 939) using binary logistic regression to validate the hypotheses. Regarding the qualitative approach, data were obtained through in-depth interviews with 20 hotel and restaurant entrepreneurs. The findings indicated that the normative and cognitive determinants have a direct impact on both opportunity-driven and necessity-driven entrepreneurship activity. Additionally, the study reveals that the relationship between a regulative environment and opportunity-necessity entrepreneurship activity is moderated by educational support. The results provided new insights into Thailand’s hospitality-oriented entrepreneurship at large.

1. Introduction

Entrepreneurial activities play a crucial role in the evolution of society, the promotion of new economic models, and the development of a country’s wealth and employment opportunities (Fu et al. 2019). Entrepreneurs contribute to the overall progress and prosperity of a nation by generating employment opportunities, stimulating investment, and introducing innovative solutions to societal challenges, thereby benefiting both the economy and individuals’ welfare.

Thailand is widely recognized as a highly popular global tourist destination, creating the tourism sector as a pivotal contributor to the country’s national economy. With diverse exceptional tourist attractions scattered throughout the country, Bangkok stands out as a prominent and enduringly popular destination, consistently receiving numerous accolades in the field of tourism. Notably, Bangkok was honored with the esteemed “World’s Best Honor” award by Travel and Leisure Magazine in multiple years, including 2008, 2010, 2011, 2012, and 2013. Furthermore, it was recognized as the “Favorite Leisure City in the World” at the 2019 Business Traveler China Awards Ceremony (Krungsri Research 2021). Consequently, the hospitality industry, as the cornerstone of Thailand’s tourism sector, has witnessed intense competition and continual expansion to cater to a growing clientele. The hotel industry places a strong emphasis on service quality, recognizing that exceptional service leads to increased customer satisfaction and loyalty (Lu et al. 2015). The economic impact of the combined hotel and food service sectors made a substantial contribution of THB1.03 trillion, equivalent to 6.1% of Thailand’s GDP in 2019 (Krungsri Research 2021).

The contribution of hospitality entrepreneurship is also considered the backbone of economic development in several nations. For example, Lee et al. (2017) postulated that early-stage café entrepreneurial activities can drive local economic development in Malaysia. Similarly, Wang et al. (2019) explained that studying motivating factors toward entrepreneurial activities in the tourism and hospitality sector can nurture economic development in China. Skokic et al. (2016) emphasized the key drivers of immense economic impact on national development, such as the socio-economic environments for hotel entrepreneurial activities in Croatia. From a global perspective, Li et al. (2020) articulated that the relationship of the country-level institutional environment plays a catalytic role in fostering hospitality-oriented entrepreneurial aspirations and activities. The interrelationship between entrepreneurship and institutions has underscored the significance of a conducive institutional environment as a pivotal determinant in nurturing entrepreneurial pursuits and fostering robust economic growth (Henrekson and Sanandaji 2011). Consequently, Boettke and Fink (2011) focused on the imperative of establishing and upholding robust institutions that represented the instrumental in cultivating economic growth and facilitating overall development.

While previous research has investigated hospitality-oriented entrepreneurial activities and business environments at the country level, further work is needed, particularly with qualitative approaches to examine how changes in business environments immensely impact entrepreneurial activities. Notably, Fu et al. (2019) reviewed and included 108 articles that vastly contributed to entrepreneurship in the hospitality industry, and they found that the amount of research articles on tourism and hospitality entrepreneurship is lower than anticipated. According to the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor study, entrepreneurial aspirations can be categorized into two types: necessity-motivated entrepreneurship (starting a business due to limited employment options) and opportunity-motivated entrepreneurship (launching a business due to available economic opportunities) (Reynolds et al. 2002). Understanding both opportunity and necessity-based entrepreneurship provides insight into the reasons why individuals start their ventures. Additionally, examining institutional environments (including regulatory, cognitive, and normative dimensions) and their relationship with the opportunity/necessity of entrepreneurial activities offers valuable insights into how regulations, policies, and the nation’s entrepreneurial culture influence hospitality-oriented entrepreneurial activities at large. Governments in many countries have invested in supporting and incubating entrepreneurial initiatives and trajectories. As a result, educational institutions play a role in enhancing and facilitating entrepreneurial activities. Walter and Block (2016) suggested that entrepreneurship education and support at universities foster entrepreneurial decision-making, which is embedded within the country, subsequently facilitating entrepreneurial activities.

Based on the above-mentioned reasoning, the primary aim of this study is to investigate the determinants influencing opportunity-driven and necessity-driven entrepreneurship within the Thai hospitality industry through the lens of institutional theory. The central focus lies in analyzing how the institutional environment either facilitates or obstructs the establishment and expansion of ventures in this sector. By delving into the dynamic interplay between the country’s institutional factors and entrepreneurial behaviors, the research aims to make a significant contribution to the scholarly discourse on entrepreneurship and institutional theory. As such, our study makes a substantial contribution by examining the influence of diverse institutional environments on various forms of entrepreneurial motivation, while also considering the moderating role of educational support within Thailand’s hospitality industry. Furthermore, this research aims to enhance the existing literature on hospitality entrepreneurship by offering fresh insights into both macro- and micro-level situational contexts within the country. To achieve comprehensive findings, our study employs a combination of quantitative and qualitative methodologies.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Institutional Theory and Entrepreneurship

Drawing upon the theory of institutional theory, the theory underlines the understanding of political, social, and cultural institutions that shape the values, norms, and behaviors of individuals in society (Bruton et al. 2010; North 1990). Scott (1995) further expands on this concept by conceptualizing institutions as three interrelated systems: cognitive constructions, normative rules, and regulative processes. These multifaceted systems provide a comprehensive understanding of how institutions influence entrepreneurial phenomena and have been widely employed in entrepreneurship research to explore various aspects of the field. In summary, the works of Bruton et al. (2010), North (1990), and Scott (1995) provided distinctive viewpoints on institutional theory, examining its impact on entrepreneurship in emerging economies, its role as the rules of the game in shaping economic behavior, and its influence on organizational behavior and structure, respectively. Collectively, these works have enriched our understanding of the importance of institutions in various contexts within the realms of economics and social sciences.

It is known that three determinants of institutional pillars are interconnected and serve as a foundation for individuals’ decision-making processes, particularly regarding entrepreneurial actions and engagement (Zhai et al. 2019). This perspective aligned with the findings of Bruton et al. (2010), who concluded that institutional environments play a crucial role in driving the success of entrepreneurial activities. On the other hand, Hwang and Powell (2005) suggested that institutional factors simultaneously created both entrepreneurial opportunities and constraints, directly influencing the rate of entrepreneurial activity. This concept is consistent with the work of Dheer (2017) who argues that individuals’ perceptions regarding the feasibility and desirability of starting a new business are inherently shaped by the institutional frameworks within their respective countries. The relationship between environmental determinants and entrepreneurial activity was examined by Alvarez et al. (2011), which compared regional differences in Spain. The research’s conclusions suggested that diverse institutional contexts in various regions of Spain had an impact on entrepreneurial activity. The study showed that areas with favorable institutional settings, such as those with encouraging policies and resources, had higher levels of entrepreneurial activity. In the same vein, the work of Urbano et al. (2019) provided a comprehensive review of research conducted over twenty-five years on the interplay between institutions, entrepreneurship, and economic growth. The study highlights the key findings and insights gained from various studies in this field. It examined the role of institutions in fostering entrepreneurship and its subsequent impact on economic growth.

Therefore, it is recognized that the nature of institutional environments plays a crucial role in the economic process, highlighting the importance of investigating how each institutional dimension influences individuals’ intentions to establish their own businesses (Kumar and Borbora 2016).

2.2. Opportunity-Necessity-Driven Entrepreneurship

The research conducted by Reynolds et al. (2002) highlights the significance of contextual factors, such as social, economic, and political conditions, in shaping individuals’ likelihood of engaging in entrepreneurial endeavors. Exploring this realm of entrepreneurship offers valuable insights into the potential contributions of entrepreneurial activities to economic growth and employment generation. Furthermore, identifying different categories of entrepreneurs helps us comprehend the supportive environments that foster entrepreneurial pursuits (Hessels et al. 2008). However, there remains a lack of consensus and a need for further exploration regarding the entrepreneurial involvement of both opportunity-driven and necessity-driven entrepreneurs (Van der Zwan et al. 2016).

In the well-established strand of entrepreneurship literature, opportunity-based entrepreneurs are those who decide to launch their own firm as a result of a perceived opportunity. They engage in entrepreneurial activities driven by various factors, including the desire for success, independence, and social advancement (Bosma and Harding 2006). According to the research conducted by Van der Zwan et al. (2016), opportunity-motivated entrepreneurs tend to carefully plan their path to independence and establish ventures within their area of expertise (Wennekers et al. 2005). This strategic approach is associated with higher survival rates and business growth (Liñán et al. 2013).

On the other hand, those who are self-employed because of necessity are considered to practice necessity-based entrepreneurship (Reynolds et al. 2002). This type of entrepreneurship typically arises from various factors such as unemployment, familial issues, or personal dissatisfaction with their current circumstances, compelling them to start their own businesses (Van der Zwan et al. 2016). Necessity entrepreneurs often operate in consumer-focused industries, reflecting their preference for more accessible and less challenging market segments (Sambharya and Musteen 2014). Consequently, this form of entrepreneurship is associated with lower levels of uncertainty and has a higher likelihood of achieving success (Valdez et al. 2011).

The incorporated variables in the study sought to analyze the influence of institutional environments, encompassing regulatory, cognitive, and normative dimensions, on entrepreneurial activities. Regulations, policies, and a nation’s entrepreneurial culture all wield significant influence over the landscape of hospitality-oriented entrepreneurship. Gaining an understanding of these institutional factors is crucial for identifying the challenges or opportunities that entrepreneurs encounter in the industry. Also, this study considers the substantial investment by governments in supporting entrepreneurial endeavors in numerous countries, and the significance of entrepreneurship education and university support becomes evident. By honing entrepreneurial decision-making skills through education, universities can actively contribute to cultivating a more dynamic entrepreneurial ecosystem within the nation. Consequently, this fostering of a robust ecosystem can fuel the growth of hospitality-oriented entrepreneurial activities, fostering economic development and driving innovation within industry.

2.3. Regulative Environment and Opportunity/Necessity-Driven Entrepreneurship Activities

Regulatory institutions play a crucial role in shaping the regulatory environment within a country. Regulatory institutions can either establish or adopt a model of rational actor behavior that includes laws, rules, policies, and government initiatives aimed at promoting specific socially acceptable behaviors, which in turn impact entrepreneurship (Bruton et al. 2010; Stenholm et al. 2013). The regulatory dimension influences entrepreneurial activity during the formation stage by either facilitating or impeding the process and guiding entrepreneurial behavior through the implementation of regulations (Baumol and Strom 2007).

Economies with fewer restrictions, freer markets, and lower entry barriers tend to offer more entrepreneurial opportunities and lower start-up costs (Ayyagari et al. 2007). On the other hand, economies with strict government regulations tend to constrain the growth and expansion of businesses (Capelleras et al. 2008). As such, government regulations and regulatory policies are essential in fostering an atmosphere where opportunity-driven businesses can thrive. Entrepreneurs have more freedom to investigate and take advantage of opportunities when there are fewer regulations, freer marketplaces, and lower entry barriers. Government programs that remove obstacles to growth and entry, make it easier to access resources, and provide training and support materials can further improve the entrepreneurial ecosystem for opportunity-driven entrepreneurship (Van Stel et al. 2007).

Furthermore, government regulations and legislation also play a crucial role in shaping the environment that fosters necessity-oriented entrepreneurship. In certain cases, complex and burdensome legal frameworks can create barriers to traditional employment, leading individuals to opt for self-employment as a more viable option. Moreover, the decision to pursue necessity-driven entrepreneurship can be influenced by government initiatives aimed at assisting individuals in financial distress or providing them with the necessary training and resources to embark on entrepreneurial ventures (Dzingirai 2021). Therefore, the first two hypotheses have been formulated as follows:

H1.

Regulative environment influences opportunity-driven entrepreneurship.

H2.

Regulative environment influences necessity-driven entrepreneurship.

2.4. Normative Environment and Opportunity-Necessity-Driven Entrepreneurship Activities

Normative institutions are considered as societal norms, values, and beliefs to control human conduct. While values are desirable standards or goals, social norms are the accepted ways to achieve some valued ends (Scott 2008). Both of these are accepted, spread, and socially shared by people (Veciana and Urbano 2008). Values and norms in the entrepreneurial world guide people’s perceptions of entrepreneurship and also determine what people and organizations must do in terms of social obligations and levels of interaction (Bruton et al. 2010). According to Busenitz et al. (2000), the normative dimension in a specific nation affects how people view being an entrepreneur as a desired professional path that commands respect and status. Culture is referred to as the collective programming of the mind, much like normative institutions (Hofstede 2001), and it has a different impact on entrepreneurial activity and economic outcomes in every nation (Williams and McGuire 2010). According to the GEM model, entrepreneurial, cultural, and social norms result from a collection of beliefs and attitudes about entrepreneurship that is specific to a given context (Levie and Autio 2008). These attitudes and beliefs help society accept entrepreneurship as a respectable career path and a high status (Aleksandrova and Verkhovskaya 2016). Based on these factors, the normative environment that reflects societal approval can support a nation’s entrepreneurial climate and encourage people to start their own businesses.

The study by Li et al. (2020) focused specifically on the normative side and explored how the institutional environment affected the opportunity and necessity of entrepreneurship in the hospitality industry. The research’s conclusions showed that the normative institutional context has a big impact on entrepreneurial activity in the hospitality industry. It was discovered that opportunity entrepreneurship in the industry is facilitated by a favorable normative environment, characterized by societal norms and values that support and encourage entrepreneurship. In such a setting, people were more likely to view entrepreneurship as an attractive and viable career option, which increased the incidence of opportunity-driven entrepreneurial activity. In contrast, an unsupportive normative environment was linked to a higher prevalence of necessity-driven entrepreneurship, which was prompted by individuals’ few options and external pressure. As such, the significance of creating a favorable normative environment greases the wheel of entrepreneurship activity and development (Li et al. 2020). Based on the above-mentioned literature, hypotheses 3 and 4 have been formulated as follows:

H3.

Normative environment influences opportunity-driven entrepreneurship.

H4.

Normative environment influences necessity-driven entrepreneurship.

2.5. Cognitive Environment and Opportunity-Necessity-Driven Entrepreneurship Activities

The cognitive environment encompasses subjective values, ideas, and cultural influences that shape the behavior and perception of entrepreneurship (Bruton et al. 2010; Stenholm et al. 2013). It is crucial to understand how entrepreneurship is perceived and how it impacts individuals’ attitudes toward independent thinking, risk-taking, and undertaking new ventures (Harrison 2008). Self-efficacy, which relates to individuals’ confidence in their ability to engage in entrepreneurial activities, plays a significant role in the cognitive framework. It influences an individual’s decision to pursue entrepreneurship and validates the feasibility of entrepreneurial opportunities (Busenitz et al. 2000). Moreover, an individual’s perception of an opportunity has been found to be a strong predictor of their inclination to start or join a business, leading to increased entrepreneurial activity (Stuetzer et al. 2014). This is in line with the work of Li et al. (2020) that found cognitive environments, such as self-efficacy and the perception of entrepreneurial opportunities, play a significant role in determining whether individuals choose to engage in entrepreneurship. These cognitive factors can predict an individual’s propensity to start a business and influence their decision-making process in the hospitality sector. This notion aligns with the findings of Roomi et al. (2018) that the cultural-cognitive aspect of an institution also mirrors how individuals perceive their cognitive capabilities, which play a crucial role in facilitating their involvement in entrepreneurial endeavors. Hence, our hypothesis proposes a relationship between the institutional environment’s cognitive determinant and entrepreneurship activity in the hospitality sector that is motivated by both opportunity and necessity as follows.

H5.

Cognitive environment influences opportunity-driven entrepreneurship.

H6.

Cognitive environment influences necessity-driven entrepreneurship.

2.6. The Moderating Role of Educational Support

Educational support can include various forms such as education programs, training, entrepreneurship courses, mentorship programs, business networks, and financial assistance tailored for aspiring entrepreneurs. These resources aim to enhance individuals’ knowledge, skills, and confidence in embarking on venture creation and activity. The work of Bergmann et al. (2018) aligns with this notion. They investigated the entrepreneurship ecosystem in higher education establishments. The study looked at the numerous elements that affect entrepreneurship in academic settings and investigated how universities might support an entrepreneurial ecosystem by examining the programs, initiatives, and policies put in place by academic organizations to encourage entrepreneurship among staff, faculty, and students. Therefore, it is crucial to foster an entrepreneurial culture through educational support to promote creativity, knowledge sharing, and the growth of entrepreneurial abilities. As such, according to institutional theory, individuals’ intents and behaviors, including their goals for entrepreneurship, are significantly shaped by the sociocultural and educational context in which they are entrenched (Wannamakok and Liang 2019).

Considering educational support as a moderator aligns with the work of De Clercq et al. (2013) who have incorporated the education system within the country as the moderator into their framework to investigate nations’ entrepreneurial activities. This was confirmed by the work of Wannamakok and Liang (2019) that business environments and the role of entrepreneurship education can influence entrepreneurial aspirations. By increasing or lessening the effect of the regulatory environment on entrepreneurial activity, educational support can also play a moderating function in the entrepreneurship context. For instance, educational support can give entrepreneurs the information and abilities they need to successfully negotiate the regulatory intricacies in a highly regulated environment with multiple bureaucratic obstacles, lowering entry barriers and encouraging entrepreneurial activity. As such, the level of business and management education that provides good and adequate preparation for starting up and growing new firms within the country should be taken into consideration. Hence, the last three hypotheses propose a relationship between the institutional environment determinants and opportunity-necessity-driven entrepreneurship activity in the Thai hospitality industry as follows.

H7.

Educational support moderates the relationship between a regulative environment and opportunity(a)-necessity entrepreneurship(b).

H8.

Educational support moderates the relationship between normative environment and opportunity(a)-necessity entrepreneurship(b).

H9.

Educational support moderates the relationship between cognitive environment and opportunity(a)-necessity entrepreneurship(b).

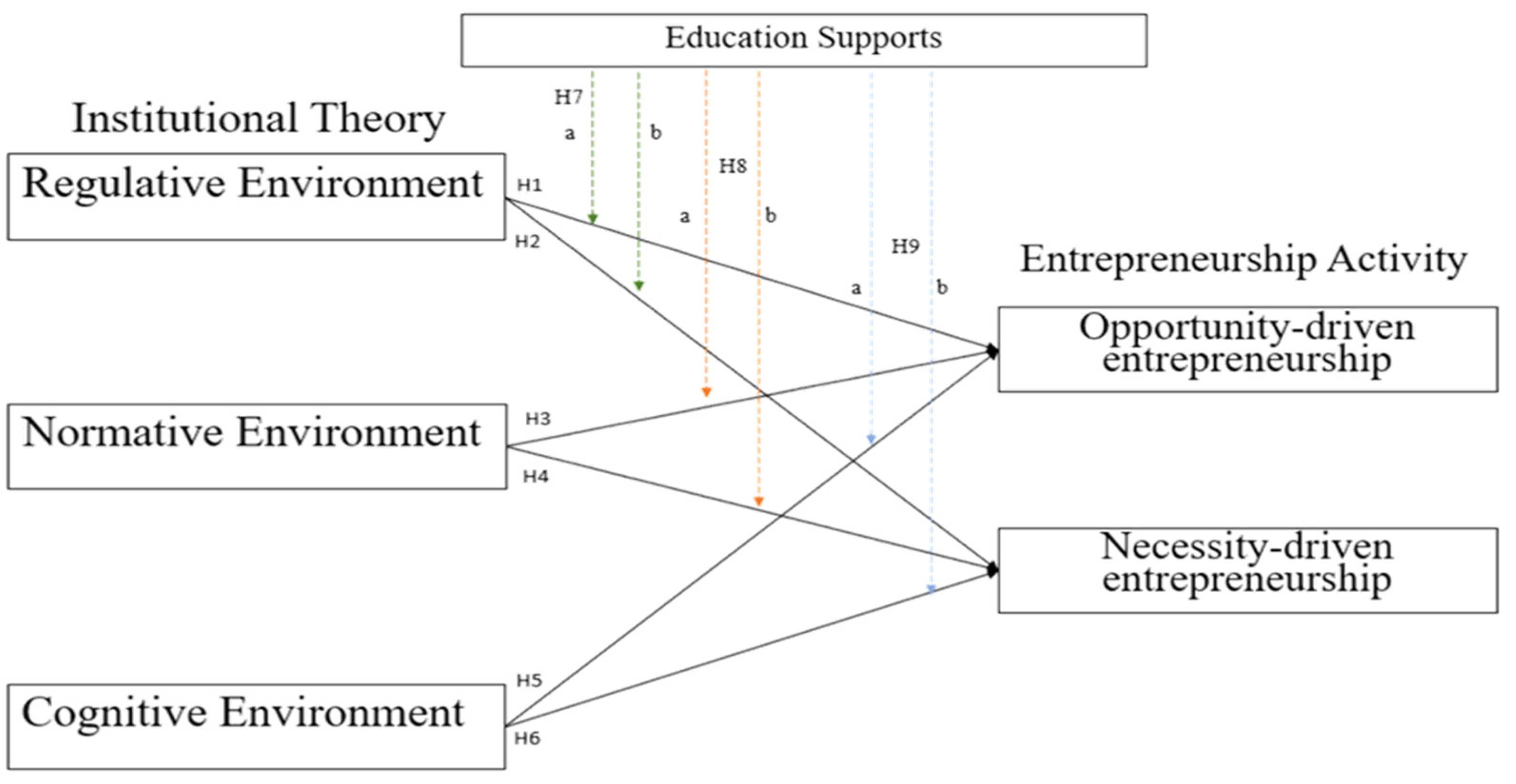

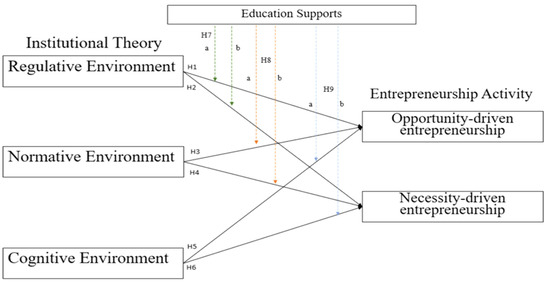

In this study, we utilize a theoretical framework (Figure 1) to conceptualize the above-mentioned relationships. Thus, the framework provides a comprehensive model for understanding the interactions among these key factors.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework.

3. Methodology

This mixed-method research followed the sequential explanatory approach of Creswell et al. (2003). Sequential explanatory employed a research design that utilizes both quantitative and qualitative methods in two consecutive phases. Quantitative data were collected and analyzed using statistical techniques to uncover patterns and relationships within the data, providing general conclusions about the research population.

Subsequently, the second phase involved gathering qualitative data through methods like interviews, focus groups, or open-ended surveys to delve deeper into the quantitative findings. This qualitative data offered explanations, context, and insights, helping to understand the reasons behind the quantitative results, to explore participants’ perspectives and experiences.

The integration of both quantitative and qualitative approaches in a sequential explanatory design allows researchers to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the research topic. This design proved particularly beneficial when initial quantitative findings raised intriguing questions or unexpected results, warranting further exploration in the qualitative phase. By combining these methods, researchers could provide a more nuanced and meaningful interpretation of the research findings, enhancing the validity and reliability of the research outcomes and leading to well-informed and comprehensive conclusions.

3.1. Quantitative Approach

The research extensively relies on secondary data obtained from reputable professional institutions to establish a robust and reliable dataset. One significant source derived from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM), a multinational research institution that consistently and comprehensively evaluates entrepreneurship and its characteristics across various countries and time periods. GEM’s extensive research project aims to gather representative data from as many countries as possible. The survey questions employed by GEM encompass a wide range of variables related to social values, personal attributes, and diverse entrepreneurial activities. To minimize translation errors and cultural biases, the survey questions were designed to elicit binary responses (yes/no) (Bergmann et al. 2014; Bosma and Harding 2006).

Additionally, another valuable data source stemming from the arguments presented in Adam Smith’s renowned book, “The Wealth of Nations,” which serves as the basis for the development of the Economic Freedom Index. According to these arguments, the presence of fundamental institutions that safeguard individuals’ freedom to pursue their own economic interests has led to enhanced prosperity for society at large. The index includes data from 117 countries, primarily consisting of developing and emerging market economies, which have demonstrated improvements in their overall Economic Freedom Score. Out of 970 Thai entrepreneurs classified as hospitality-oriented, the study included a total of 939 valid samples for further analysis using binary logistic regression. The choice of adopting binary logistic regression is based on the nature of the research question and the type of data being analyzed. Binary logistic regression is a frequently employed statistical method when the outcome variable is binary or categorical with only two levels. It proves especially valuable in examining the connection between predictor variables and a binary outcome, such as yes/no scenarios. By estimating the probability of an event happening based on the predictor variable values, binary logistic regression also offers insights into the odds ratio, which indicates the strength and direction of the relationship between the predictors and the outcome. Given that the research question of this study involves predicting a binary outcome using predictor variables, binary logistic regression is indeed the appropriate statistical approach to address the objectives of the research. More specific details regarding this index are provided in Appendix A.

3.2. Qualitative Approach

Data Collection

A technique used in sample selection is quota sampling. To ensure representativeness in accordance with the researcher’s goals, it entails determining the sample’s structure. The quantity and features of the groups to be included in the sample are decided by defining the sample’s types of business. In the realm of qualitative research, the interview protocol plays a pivotal role in unraveling the nuanced fabric of human experiences and perspectives. Therefore, we delve into the meticulously crafted interview protocol employed in a study focusing on Thai hospitality-oriented entrepreneurs. By delving into the strategic utilization of quota sampling, the meticulous questionnaire design, and the significance of in-depth interviews, we uncover the layers of meticulous planning that underpin this research endeavor.

The journey commences with a distinct approach known as quota sampling, a deliberate method chosen to ensure a sample composition aligned with the researcher’s goals. Drawing inspiration from Yang and Banamah’s (2014) work, the study predefines both the desired number and specific characteristics of participant groups. The resultant sample pool, consisting of 10 Thai hotel entrepreneurs and 10 restaurant entrepreneurs, is thus meticulously tailored to capture the essence of the hospitality industry’s entrepreneurial landscape in Thailand.

To fortify the effectiveness of the interview process, a preliminary pilot study was meticulously orchestrated. This trial run involved mock interviews, a calculated rehearsal allowing researchers to fine tune the final questionnaire design. The questionnaire, a comprehensive instrument, artfully interweaves a spectrum of dimensions ranging from individual and company information to entrepreneurial motivation, educational support, and the multifaceted institutional environment theory. By incorporating these diverse facets, the researchers aimed to glean a holistic understanding of the entrepreneurs’ intricate world.

Guided by the wisdom imparted by Guion et al. (2001), the study embraced in-depth interviews as a qualitative research cornerstone. Acknowledging the power of interviews in unearthing participants’ viewpoints, experiences, and subjective interpretations, the researchers embarked on a journey of meticulous preparation. The interview protocol blueprint demanded meticulous groundwork, encompassing the delineation of research objectives, the identification of suitable interview subjects, and the crafting of a comprehensive interview guide. This guide, akin to a compass, charted the course of the discussions, defining the themes and questions to be explored in the conversations.

Having set the stage, the researchers embarked on the process of data collection, reaching out to potential participants via email and social media. This proactive outreach garnered a collection of 20 Thai hospitality-oriented entrepreneurs, each of whom willingly embraced the research’s backdrop and objectives. The procedural intricacies were transparently communicated, and participants were assured of their autonomy to withdraw from the study at any juncture. This commitment to ethical considerations was further solidified through the administration of informed consent forms, which every participant willingly signed.

The interviews themselves, conducted in the Thai language, exhibited a remarkable range, spanning from 30 to 60 min. This temporal variance allowed for the organic unfolding of discussions while accommodating the idiosyncrasies of each entrepreneur’s narrative. The dynamic interviews were meticulously captured in both audio and content formats, ensuring that no subtlety or nuance escaped documentation. Subsequent efforts transformed the interviews into English, a process serving as a cornerstone of precision in both phrasing and content.

Moreover, the researchers went beyond the interviews themselves, engaging in a reflective practice. Brief reflections following each interview not only enriched the researchers’ own insights but also contributed to the continual refinement of the interview protocol.

In summary, this interview protocol weaves together various strategic elements, from quota sampling to questionnaire design and the utilization of in-depth interviews, creating a comprehensive tapestry for the study of Thai hospitality-oriented entrepreneurs. The meticulous planning, ethical considerations, and commitment to capturing authentic experiences serve as hallmarks of a qualitative research endeavor driven by a quest for profound understanding. The qualitative question items can be demonstrated in the Appendix B. The detailed Interviewee demographic description is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Interviewee demographic description.

4. Results

4.1. Quantitative Results

All of the constructs were correlated in Table 2, and Table 3 revealed that the model fit was verified by including the entire model. Binary logistic regression was finally used to ensure that nine assumptions were met. To further explain, Table 2 shows that, as implied by the statement, the correlations between various elements were quantified and established using statistical analysis. Table 3 shows that the model performed well because it was able to include all of the variables. Binary logistic regression was employed and presented in Table 4 and Table 5 to confirm that certain assumptions were met. In statistical analysis, this approach is frequently used to examine the connections between factors and forecast results.

Table 2.

Correlation results.

Table 3.

Goodness-of-fit statistics.

Table 4.

Model summary results (Dependent: Opportunity Entrepreneurship; n = 939).

Table 5.

Model summary results (Dependent: Necessity Entrepreneurship; n = 939).

The analysis of correlations demonstrated that all of the significant variables were interrelated, as presented in Table 2. Additionally, the data analysis utilized Hosmer and Lemeshow’s approach, employing binary logistic regression and frequency calculations to assess how individuals fit into specific categories. All of the predictor variables were included in the analysis, as indicated in Table 3, and the chi-square test revealed that all three models were statistically significant (p < 0.001). This suggests that the complete models exhibited a much better fit and performance compared to the null model. Furthermore, the Omnibus test consistently yielded significant results (p < 0.01), indicating that the coefficients of the hypotheses were not zero. Therefore, the Hosmer–Lemeshow test (HL test) is widely recognized as a goodness-of-fit test for binary logistic regression (Paul et al. 2013).

According to Table 4, Model 1 initially included control variables of background, education level, and cultural support for the entrepreneurship index. The results indicated that these control variables had a slightly significant contribution to opportunity entrepreneurship activity in all three models. Then, independent variables were added to test H1, H3, H5, H7(a), H8(a), and H9(a) where Thai hospitality-oriented entrepreneurs’ perceptions of regulative, normative, and cognitive environments are introduced to examine their opportunity-driven entrepreneurship activity in Model 2. The results showed that Thai hospitality-oriented entrepreneurs’ perceptions of the regulative environment did not play a critical role in embracing their opportunity-driven entrepreneurship activities (β = 0.173, n.s.), rejecting hypothesis 1. This suggests that regulations may have some influence on entrepreneurship endeavors in the hospitality industry, but they were not considered essential in determining whether business owners would undertake opportunity-driven business activities. Instead, factors such as resource availability, market demand, and rivalry were believed to play a bigger role in influencing entrepreneurial behavior.

On the other hand, Thai hospitality-oriented entrepreneurs’ perceptions of the normative (β = 0.511, p ** < 0.01) and cognitive environments (β = 0.540, p *** < 0.001) play a vital role in nurturing opportunity-driven entrepreneurship activity, confirming hypotheses 3 and 5, accordingly. The study’s findings revealed that normative and cognitive environment perceptions of Thai entrepreneurs significantly encourage opportunity-driven entrepreneurship activity in the hospitality sector. These elements may affect an entrepreneur’s drive, risk-taking tendencies, and decision-making processes, which, in turn, impact how well they can spot and seize business opportunities. Thus, Thai entrepreneurs are more likely to engage in opportunity-driven activities if they believe their social environment supports entrepreneurship.

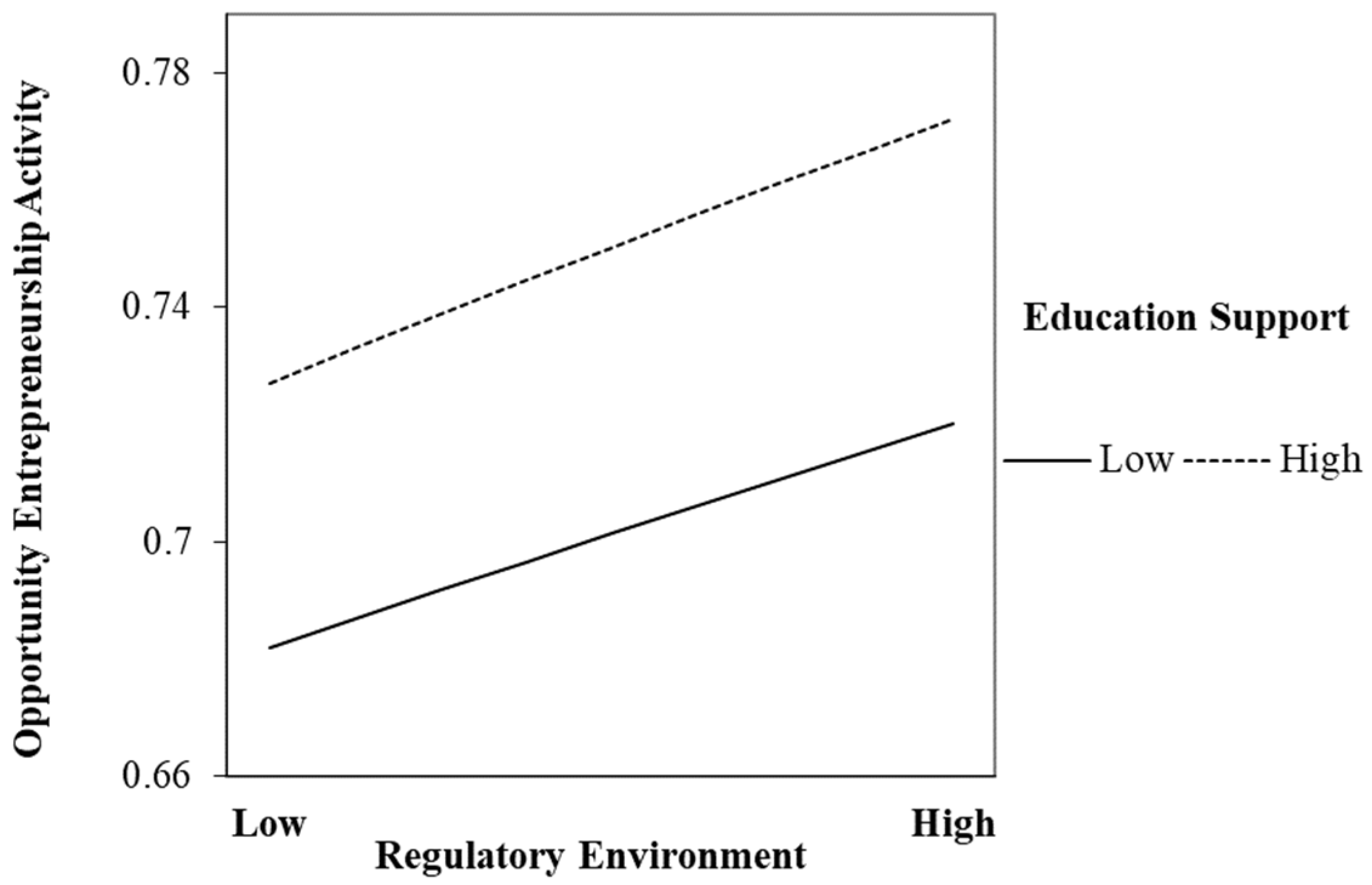

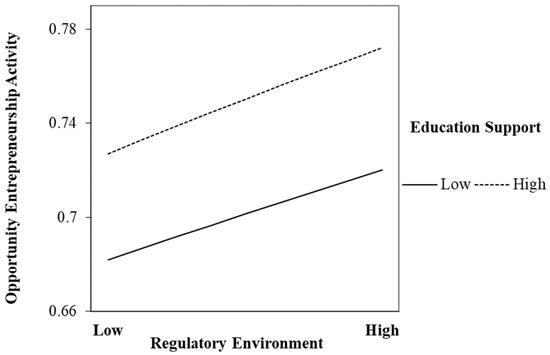

In Model 3, the moderating role of educational support had been included to further examine the relationship between the three dimensions of institutional environment theory and opportunity-driven entrepreneurship activity, validating H7(a), H8(a), and H9(a). The results showed that the moderating role of educational support strengthens the relationship between Thai hospitality-oriented entrepreneurs’ perceptions of the regulative environment and opportunity-driven entrepreneurship activities (β = 1.157, p * < 0.05), accepting hypothesis 7(a). This suggests that entrepreneurs who want to start their own firms might benefit from educational support programs that provide them with the knowledge and skills needed to understand business legislation, navigate the regulatory environment, and discover business prospects.

However, the results showed that the moderating role of educational support did not play a critical role in enhancing the relationship between normative environments (β = 0.042, n.s.) and cognitive environments (β = 0.048, n.s.) toward opportunity-driven activities, rejecting H8(a) and H9(a). To provide a more comprehensive interpretation of the obtained results, we conducted a plot of the interaction effect, as shown in Figure 2 below. According to the plot, the positive relationship between the regulatory environment and opportunity-driven entrepreneurship is strengthened when Thai entrepreneurs perceive higher educational support.

Figure 2.

The moderating effect of educational support on the relationship between regulatory environment and opportunity entrepreneurship activity.

Table 5 indicates that Model 1 was initially incorporated into the study, which involved including control variables such as background, education level, and cultural support for the entrepreneurship index. The outcomes revealed that these control variables had a minor, yet significant effect on the necessity entrepreneurship activity in all three models. Subsequently, independent variables were introduced to validate H2, H4, and H6, which involved examining the necessity-driven entrepreneurship activity of Thai hospitality-oriented entrepreneurs’ regulative, normative, and cognitive environment perceptions in Model 2. The findings demonstrated that the regulative perceptions of hospitality-focused entrepreneurs in Thailand play a crucial role in their adoption of necessity-driven entrepreneurial pursuits. This is supported by a statistically significant beta coefficient of 0.240 at a significance level of p * < 0.05, thereby confirming hypothesis 2. In this sense, Thailand’s hospitality-focused entrepreneurs and their necessity-driven entrepreneurial activities are significantly impacted by their regulatory attitudes. These perspectives include the business owners’ understanding and interpretation of the legal and political framework that governs their operations, including the laws, regulations, and guidelines that have an impact on their businesses. Similarly, the results show that Thai hospitality-oriented entrepreneurs’ normative (β = −0.540, p ** < 0.01) and cognitive environment perceptions (β = −1.557, p *** < 0.001) are critical factors in fostering necessity-driven entrepreneurship activity, validating hypotheses 4 and 6, respectively. This implies that Thai hospitality-oriented entrepreneurs’ normative and cognitive environment perceptions can also influence their necessity-driven entrepreneurship activity.

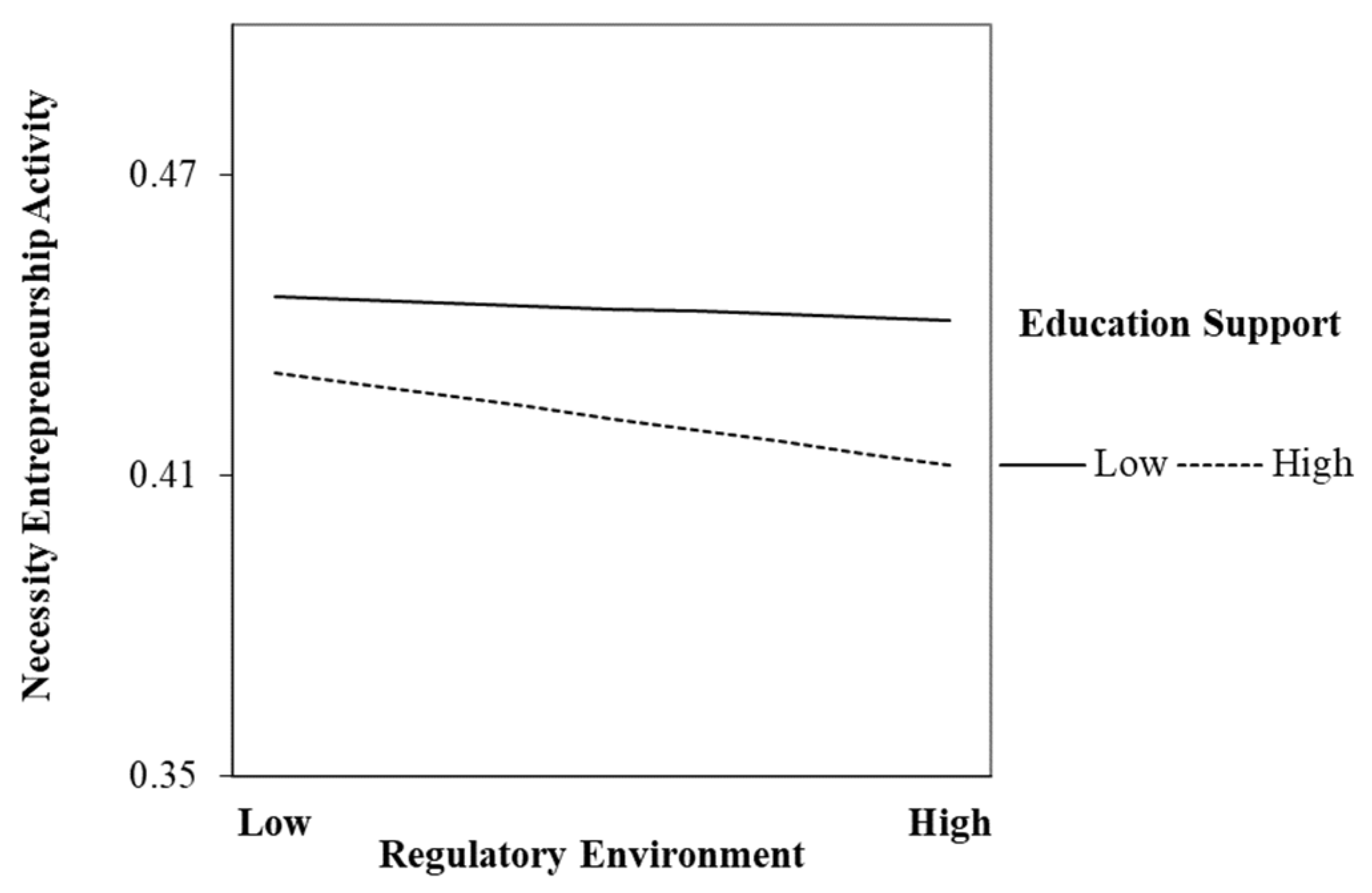

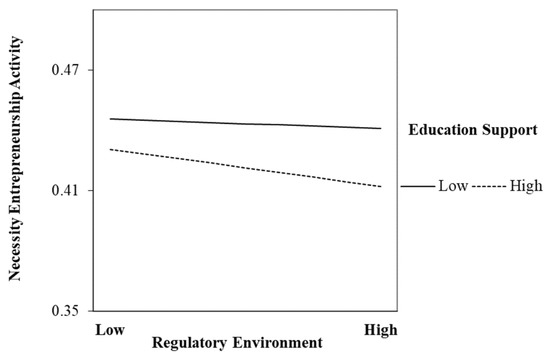

To evaluate the relationship between the three dimensions of institutional settings theory and necessity-driven entrepreneurship activity, the study introduced the moderating impact of educational support in Model 3, supporting H7(b), H8(b), and H9(b). The results showed that educational support fuels the relationship between regulative attitudes of Thai hospitality-oriented entrepreneurs and necessity-driven entrepreneurial activities (β = −1.129, p * < 0.05), supporting hypothesis 7(b). This means that educational support can enhance entrepreneurs’ understanding of the regulatory environment, thereby enabling them to comply with regulations and obtain necessary permits and licenses. This compliance has the potential to foster a favorable perception of the regulatory milieu, which in turn can catalyze necessity-driven entrepreneurship.

In contrast, the empirical data evinces that the moderating effect of educational support did not play a pivotal role in enhancing the association between normative environments (β = 0.042, n.s.) and cognitive environments (β = 0.048, n.s.) with respect to activities propelled by necessity-oriented entrepreneurship, thereby rejecting the hypotheses H8(b) and H9(b).

Furthermore, we plotted the interaction effect of the significant result. According to Figure 3 below, the relationship between the regulatory environment and necessity-driven entrepreneurship activity is nurtured when Thai entrepreneurs perceive lower educational support.

Figure 3.

The moderating effect of educational support on the relationship between the regulatory environment and necessity entrepreneurship activity.

Table 6 summarizes the causal relationships between the three determinants of institutional theory and opportunity-necessity-oriented entrepreneurship activities, as well as the overall hypothesis outcomes.

Table 6.

The summary of hypothesis outcomes (n = 939).

4.2. Qualitative Results

4.2.1. The Regulatory Landscape in Thailand: Driving Forces and Barriers

Thai hospitality entrepreneurs are significantly impacted by business regulations and laws. In the hospitality industry, the regulatory environment, which includes laws, regulations, and government efforts, can either support or impede entrepreneurial activity. The Thai government has put in place several laws and policies to encourage entrepreneurship in the hospitality sector. These regulations include financial incentives, business registration processes, and particular initiatives geared toward the growth of the travel and hospitality industries. Most of the interviewees agreed that business regulations for hotel entrepreneurship are considered the bottleneck of entrepreneurship initiatives and activities. Here are some opinions shared by the interviewees:

“When I initiated my hotel business, I encountered several regulations and rules. The process took quite a few months, which was too long. The timeframe should be adjusted to be faster than this. While the law itself is considered supportive for doing business, the extensive time and numerous inspections have been challenging.”—Interviewee A

“In Thailand, the permit application process for hotel enterprises involves multiple organizations, including municipal, district, and provincial offices. However, there is a lack of cooperation among these organizations, leading to slow processing times. As a result, corporate operations are delayed, and some enterprises, like hostels, face difficulties in obtaining the required permits or licenses.”—Interviewee D

“Hotel establishments were initially required to physically submit guest registration documents at the district office. Later, an online submission system was introduced; however, its functionality falls short of providing optimal support. As a result, this leads to slow operational procedures within hotel businesses. Furthermore, the regulation and supervision of accommodation providers lack clarity, which creates competition between hotels and alternative lodging options.”—Interviewee H

Furthermore, some of the interviewees expressed their concerns and opinions on business regulations that appear to favor foreign investors and impose higher tax burdens on local entrepreneurs. This disparity creates an uneven playing field and puts local businesses at a disadvantage. The regulations may offer preferential treatment or exemptions to foreign investors, granting them privileges and incentives not available to local enterprises. Consequently, local businesses face a heavier tax burden and may struggle to compete with their foreign counterparts. Such discrepancies in business regulations can impede the growth and development of domestic enterprises, leading to potential economic imbalances and challenges for local entrepreneurs.

“There are flaws in the way business is conducted, particularly in how regulations seem to favor powerful stakeholders and foreign investors. As a result, foreigners tend to dominate industries like hotels, restaurants, and tourism. It is unclear whether these operations adhere to tax laws and licensing requirements. Surprisingly, despite the prevalence of Chinese and Russian business owners, international entrepreneurs, especially in areas like Phuket and Pattaya, tend to avoid official examinations. The negative effects of state-supported investment policies have significantly impacted Thai businesses in various sectors.”—Interviewee B

“The tax system is one aspect that is not favorable for business owners. Start-ups and recently formed firms often begin as solo projects, and some people register their businesses to gain access to finance. Significant taxes must be paid when shares are sold to raise funds for management purposes.”—Interviewee D

However, restaurant entrepreneurs have different opinions and concerns from hotel entrepreneurs. Most restaurant entrepreneurs considered business regulations for restaurant entrepreneurship are found to grease the wheel of business initiatives and activities. Here are some exampled opinions of the interviewees.

“The process of launching a business in Thailand is not particularly difficult or fraught with obstacles. However, there might be rules and directives in place to set standards.”—Interviewee K

“Starting a business in Thailand is easy as individuals can operate without registering as a legal entity. This flexibility allows entrepreneurs to begin and run businesses as sole proprietors or partnerships using their personal identity. However, it’s essential to be aware of potential limitations and considerations regarding legal liability, tax obligations, and access to certain benefits and protections associated with registered legal entities.”—Interviewee O

“Thailand has rules in place that make it easier for people to do business in general, enabling common people to do so without the necessity for corporate registration.”—Interviewee P

“Individuals can form numerous types of businesses in Thailand, such as sole proprietorships, SMEs (Small and Medium-sized Enterprises), or corporate entities, depending on the size and nature of the firm.”—Interviewee T

4.2.2. Social Norms as a Factor Influencing the Legitimacy of Entrepreneurship

In the normative determinant, the majority of Thai hotel and restaurant entrepreneurs expressed agreement that social norms within the country still uphold the legitimacy of being an entrepreneur. The ease of doing business in a country can significantly influence the perception of entrepreneurship’s legitimacy. When the process of starting and operating a business is favorable, efficient, and transparent, it fosters a positive environment that encourages more individuals to engage in entrepreneurial activities. This ease of doing business creates a supportive atmosphere in which potential entrepreneurs feel more confident and empowered to establish legitimate firms. Here are some examples of opinions shared by the interviewees:

“In general, when we observe a company with a large customer base and positive reception, it often sparks the desire to follow suit. We might believe that starting a similar business now would allow us to ride the current trend and attract a significant audience as well. The success and popularity of such a firm can serve as a motivating factor for aspiring entrepreneurs to enter the market and capitalize on the existing demand and interest.”—Interviewee H

“It may be perceived positively depending on how smoothly the channels run, how good the technological capabilities are, and the availability of financial management information from diverse sources. These elements contribute to making the business more agile and convenient.”—Interviewee I

“The majority of Thais choose to leave their employment and become entrepreneurs because they believe that entrepreneurship offers the potential to improve their standard of living.”—Interviewee M

“The majority of Thais perceive the ease of doing business and hold a favorable attitude toward entrepreneurs.”—Interviewee P

“Thais view entrepreneurship as a straightforward way of earning revenue while enjoying the flexibility of being their own boss. This overall impression is favorable.”—Interviewee S

4.2.3. The Cognitive Views of Entrepreneurship

The cognitive environment determinant of an institutional theory also reflects how individuals perceive their cognitive ability, which is crucial in facilitating their participation in entrepreneurial ventures. Most Thai hotel and restaurant entrepreneurs have personally known someone who started a business in the past 2 years. They also believe that the perception of individuals who serve as role models or inspirations for entrepreneurship is commendable. This perception can influence their entrepreneurial intention and enable them to learn how to be successful in real-world business, thereby motivating them to engage in entrepreneurial activities. Specifically, the interviews suggest the following:

“The perception of success depends on the kind of award the business has received. For instance, if a business is awarded by a prestigious platform like Agoda, it can gain more visibility through national media and increased promotion. This recognition and publicity contribute to a positive perception of success in the entrepreneurial community.”—Interviewee H

“Personally, I often encounter successful restaurant owners who gain fame through online media, like Instagram. Their insights and experiences inspire others to consider entrepreneurship positively.”—Interviewee M

“Chefs in the culinary sector create internet content showcasing various techniques, gaining millions of followers. Web programs featuring recipes from different chefs also provide valuable learning opportunities.”—Interviewee S

4.2.4. The Role of Educational Support and Entrepreneurship

As entrepreneurs with a higher educational background, particularly those pushed by possibilities, they frequently benefit from vast social networks that promote business growth. This advantage arises from individuals’ extensive exposure to educational support, which allows them to establish relationships and gain access to key resources. Based on our interview findings, all Thai hospitality-oriented entrepreneurs agreed and emphasized the importance of educational support and that educational institutes can assist them in applying the knowledge they acquire to improve their business operations. Particularly, the interviews suggest the following:

“The university offers extensive support in the business area, providing case studies and examples from successful entrepreneurs to inspire us to learn from their vivid experiences.”—Interviewee S

“The available case studies can be applied to my own firm, enabling me to adapt, address challenges, and take preventive measures effectively.”—Interviewee J

“Universities play a crucial role in assisting entrepreneurs and students by filtering and organizing knowledge, ideas, and changing situations, guiding them in the right direction for their firms. They offer advice on current business strategies to adapt to ever-changing circumstances. Learning and exchanging knowledge with teachers and peers become essential for entrepreneurs to stay on track. Additionally, relevant theories from books remain critical for running a business successfully.”—Interviewee D

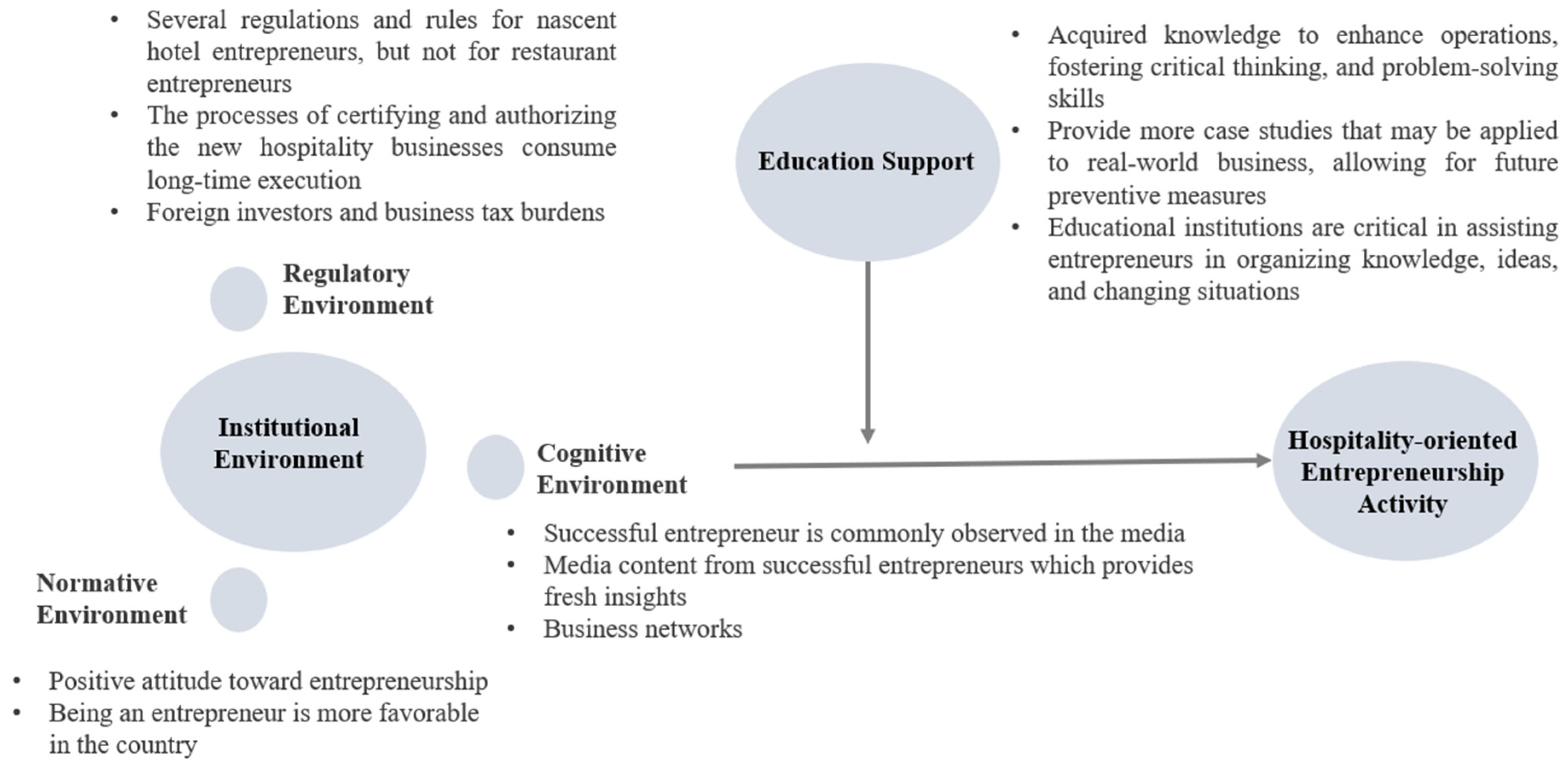

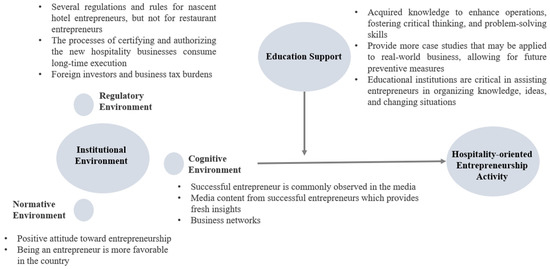

In summary, Figure 4 illustrates the interview results based on Thai hotel and restaurant entrepreneurs.

Figure 4.

The summarized interview results of Thai hotel and restaurant entrepreneurs.

5. Discussion

Entrepreneurship is critical to society’s growth, economic development, and job opportunities. The tourism industry in Thailand contributes significantly to the national economy. In this sense, the hospitality business, which is driven by exceptional service, is a cornerstone of Thailand’s tourism industry. In numerous nations, hospitality entrepreneurship is acknowledged as a catalyst for economic development, and the institutional environment and educational assistance are important elements influencing entrepreneurial activities. This study aims to explore how changing business environments affect entrepreneurship by considering a combination of quantitative and qualitative research methods to examine the influence of institutional contexts and educational support on entrepreneurial endeavors within Thailand’s hospitality industry.

Government regulations and legislation significantly impact the environment for necessity-oriented entrepreneurship. Complex and burdensome legal frameworks can discourage traditional employment and push individuals toward self-employment. In this sense, government initiatives that provide financial assistance, training, and resources to individuals in financial distress can also influence the decision to pursue necessity-driven entrepreneurship (Dzingirai 2021). The attitudes of necessity-driven entrepreneurs toward regulations have a notable impact on their engagement in entrepreneurial activities. This encompasses their understanding and interpretation of the legal and political framework that governs their businesses. The findings of Fuentelsaz et al. (2018) aligned with our results. They explicate their empirical evidence and confirm the correlation between economic freedom and entrepreneurial endeavors. This means that individuals and businesses have the freedom and ability to engage in economic activities without undue restrictions or interference from the government or other external entities. As such, economies with higher levels of economic freedom are typically associated with increased entrepreneurial activity, innovation, and economic growth. Notably, the study reveals that Thai opportunity-driven entrepreneurs view the regulatory environment as a hindrance and do not have a substantial impact on their involvement in entrepreneurial activities in the Thailand context. This reconciles most of the Thai hotel and restaurant entrepreneurs’ perspectives during interview sessions, where they identified various areas of concern such as regulations, new business registration processes, taxation, and foreign competition. Therefore, the findings suggested that entrepreneurs who pursue businesses in the hospitality industry out of necessity are strongly influenced by the presence of favorable regulatory institutions. Furthermore, the study findings indicated that normative and cognitive environment perceptions among Thai hospitality-oriented entrepreneurs are crucial in fostering opportunity-necessity-driven entrepreneurial activity. This can be explained by previous research that shows that personal cognitive schemas and societal norms play a significant role in shaping the level of entrepreneurial activities (Stenholm et al. 2013).

This can be explained by the fact that the normative environment plays a significant role in motivating both opportunity-driven and necessity-driven hospitality entrepreneurship. Consequently, local governments should tailor their policies to encourage different types of hospitality entrepreneurship based on specific entrepreneurial objectives (Li et al. 2020). Considering that the connection between institutional environment determinants and opportunity-driven and necessity-driven entrepreneurship in the hospitality sector can be strengthened through educational support, this study investigated these relationships and discovered that educational support only impacts the association between the regulatory dimension and both types of entrepreneurships in the hospitality industry. This can be explained by the work of Verheul et al. (2005) that governments often implement favorable policies to promote entrepreneurship and enhance societal appreciation for entrepreneurial endeavors. These efforts are commonly facilitated through educational systems and media channels.

Although numerous studies indicate a positive relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial aspirations and activities (e.g., Rauch and Hulsink 2015; Kautonen et al. 2015), there is also conflicting evidence that suggests a potential negative influence (e.g., De Clercq et al. 2013). This disparity indicates that the outcomes of entrepreneurship education can be contingent upon the surrounding environmental conditions. Therefore, entrepreneurship is influenced by the interplay between individuals and their contextual surroundings. Recent meta-analyses have emphasized the need for exploring potential factors and the moderating effects of educational support (Wannamakok and Liang 2019; Walter and Block 2016). In line with this, our findings also support the suggestions put forward by Wannamakok and Liang (2019) who proposed exploring the interplay between education determinants and institutional contexts and their impact on the outcomes and growth of new ventures. This can be achieved through the utilization of theoretical and empirical analysis to present various perspectives on the contextual nature of entrepreneurship education in relation to a country’s institutional environments (Walter and Block 2016) accordingly.

6. Conclusions

The findings of this study indicated that regulatory perceptions among Thai-oriented entrepreneurs did not significantly influence their engagement in opportunity-driven entrepreneurship activities. Instead, normative, and cognitive environment perceptions were found to play a crucial role in nurturing opportunity-driven entrepreneurship in the hospitality sector. Additionally, the study examined the moderating role of educational support and found that it strengthened the relationship between regulatory perceptions and opportunity-driven entrepreneurship. However, educational support did not have a significant impact on the relationship between normative and cognitive environments and opportunity-driven activities. On the other hand, the significant role of regulative perceptions strongly influences their engagement in necessity-driven entrepreneurial activities. In this sense, normative and cognitive environment perceptions were found to be crucial determinants in fostering necessity-driven entrepreneurship. The study also introduced the moderating effect of educational support and found that it positively strengthens the relationship between regulative attitudes and necessity-driven entrepreneurship. However, educational support did not have a significant impact on the association between normative and cognitive environments and necessity-driven activities.

7. Theoretical Implications

This study adds to the current literature by investigating the influence of the country-level institutional environment in hospitality entrepreneurship, an area that has received little attention in previous tourism and hospitality entrepreneurship studies. Unlike previous studies that focused primarily on personal and destination characteristics, our research stressed the relevance of examining the institutional environment in the context of tourism and hospitality entrepreneurship. Furthermore, our research not only examined the impact of the country’s institutional framework on hospitality entrepreneurship, but it also conducted a comparison analysis between the hospitality sector and the larger all-industry sector. This comparative method provides useful insights into the distinguishing qualities of hospitality entrepreneurship.

This study also introduces novel insights into the diverse forms of entrepreneurial motivation in the context of hospitality entrepreneurship. The empirical findings suggested that necessity-driven hospitality entrepreneurs are positively influenced by favorable regulatory institutions, while normative institutions act as encouraging factors for their endeavors. Conversely, opportunity-driven hospitality entrepreneurship is positively influenced by cognitive and normative institutions. To the best of our knowledge, this study is one of the pioneering works that examine the differential impacts of various institutional environments on different types of entrepreneurial motivation in the tourism and hospitality industry. By doing so, we contribute to a more comprehensive and thorough understanding of the intricate relationships between the macro-level institutional environment and micro-level entrepreneurial motivation in the realm of hospitality entrepreneurship.

8. Practical Implications

The Thai government must keep pace with the rapidly evolving global landscape in terms of sustainable production, services, and food. The progress in these areas within Thailand has been relatively sluggish compared to more developed countries. If the government can disseminate knowledge and implement policies that support sustainable practices in the hotel and food industries, it will contribute to long-term sustainability and progress in the country. For instance, incentivizing sustainable practices can be achieved through measures such as tax reductions or the acceptance of carbon credits as tax deductions for hotels that generate them and reduce plastic consumption. Moreover, when a hotel adheres to environmental, social, and governance (ESG) policies, the government should acknowledge and commend them as role models for others. However, it is crucial for the government to ensure transparency and fair evaluation criteria in their actions.

In terms of knowledge development, there are training programs available to enhance the competencies of personnel from government agencies that promote education. These programs aim to provide access to funding sources for entrepreneurs. The role of educational institutions is paramount in equipping entrepreneurs with knowledge, shaping their attitudes, providing access to networks and resources, facilitating adaptation to changing contexts, and driving economic and societal impact. By addressing the needs of entrepreneurs in navigating the institutional landscape, educational support plays a vital role in fostering a conducive environment for entrepreneurial success. As a result, offering training programs for personnel in the hospitality industry can enhance their skills and capabilities, thereby contributing to the development of human resources in the hospitality sector.

Finally, the related authority should facilitate access to affordable financing options, and providing tax incentives for new entrepreneurs are essential measures to promote entrepreneurship. By granting access to funding sources with low-interest rates, aspiring entrepreneurs can obtain the necessary capital to start their businesses. Furthermore, reducing tax burdens for new businesses can alleviate financial constraints and encourage more individuals to venture into entrepreneurship. These measures collectively foster a supportive environment for new entrepreneurs and stimulate economic growth.

9. Limitation and Future Research

The primary limitation of this study lies in its exclusive emphasis on perceptions and their influence on entrepreneurial activities, disregarding potential contributions from other factors. While examining the impact of regulatory, normative, and cognitive environment perceptions on opportunity-driven and necessity-driven entrepreneurship, the study failed to consider external factors or individual characteristics that might also shape entrepreneurial behavior. This narrow focus may restrict the overall comprehension of the intricate interplay of elements influencing entrepreneurship in the hospitality sector. To attain a more comprehensive understanding, future research could encompass a broader array of variables and factors, facilitating a deeper exploration of the dynamics that shape entrepreneurial activities in this industry. By addressing these research areas, it can contribute to significant progress in understanding hospitality-oriented entrepreneurship, offering valuable insights and guidance for policymakers, practitioners, and aspiring entrepreneurs in the industry. These future studies have the potential to enrich the existing knowledge landscape and provide practical implications for the development and support of entrepreneurial endeavors within the hospitality sector.

Author Contributions

In the process of developing this study, W.W. and W.Y. played crucial roles by generating the main conceptual ideas. W.W. took the lead in shaping the research approach, where he skillfully employed both quantitative and qualitative methodologies. Specifically, W.W. managed the quantitative analysis and also delved into the qualitative exploration alongside W.Y. The project administration was skillfully overseen by W.Y., ensuring smooth coordination. W.W. led the research investigation, spearheading the entire journey of exploration. Additionally, the authors collectively secured the necessary funding, with contributions from both W.W. and W.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Internal funding from research department, Dusit Thani College, Bangkok. Thailand.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Institutional Review Board Statement and ethical approval. Therefore, the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all interviewees involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions. The study’s findings and conclusions were drawn from the available data within these constraints, and any potential implications stemming from the unavailable data should be interpreted in light of these restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Quantitative Variables

| Variable | Index | Level | Measurement/Source |

| Dependent Variables | |||

| Opportunity-driven entrepreneurship activity Necessity-driven entrepreneurship | GEM 2015–2018 | Individual Level | 1 = Opportunity/Necessity entrepreneurship, 0 = otherwise (Li et al. 2020) |

| Independent Variables | |||

| Cognitive Environment Do you know someone personally who started a business in the past 2 years? | GEM 2015–2018 | Country Level | 1 = Yes, 0 = otherwise (Junaid et al. 2019) |

| Normative Environment In my country, it is easy to start a business. | Country Level | 1 = Yes, 0 = otherwise (Arabiyat et al. 2019) | |

| Regulative Environment The country’s regulatory framework allows and facilitates individuals to run businesses. | IEF 2015–2018 | Country Level | A qualitative assessment (0–100) (Li et al. 2020; Fuentelsaz et al. 2018) |

| Moderating Effect | |||

| Educational Support In my country, colleges and universities provide good and adequate preparation for starting up and growing new firms. In my country, the level of business and management education provides good and adequate preparation for starting up and growing new firms. | GEM 2015–2018 | Country Level | 9 Likert’s Scale (Ranging from 1 = Completely fail to 9 = Completely true) (Sá and de Pinho 2019) |

Appendix B. Qualitative Question Items

The questionnaire for the qualitative approach can be broken down into 5 parts as follows.

Part 1: Personal Data

- 1.

- Age: _________ years

- 2.

- Gender: O female O male

- 3.

- Are you currently a self-employed entrepreneur? O yes O noIf not, do you intend to start your own business? O yes O no

- 4.

- When did you officially start the company? ____/____ (Month/year)

- 5.

- In which industry did you start the company?__-_______________________________

- 6.

- Please briefly describe the activities of your company:__________________________Part 2: Entrepreneurial motivation in Thailand

- 7.

- How would you describe the entrepreneurial motivation of a typical Thai person?

- 8.

- What was your motivation to become an entrepreneur?

- 9.

- Does Thailand offer good business opportunities for your company? O yes O no Why?

- 10.

- How and when did you recognize the opportunity for your business?Part 3: Resources Human capital

- 11.

- Do you think educational institutions could/should improve their entrepreneurial education? O yes O noCan you elaborate and provide suggestions?

- 12.

- Do you think colleges and universities provide good and adequate preparation for starting up and growing new firms?

- 13.

- Do you think the level of business and management education provides good and adequate preparation for starting up and growing new firms?

- 14.

- Did you work in/own a start-up before this one? O yes O noIf yes, how many years of entrepreneurship experience did you have before this company?

- 15.

- Entrepreneurship experience ______ years

In which industries have you gained work experience (If not restaurant and hotel industry)?

Part 4: Product and Market Knowledge

- 16.

- At the time of the market entry did you have a complete business plan?O yes O no If yes, how frequently did you adjust it?__________________________________

- 17.

- Please submit 100 points to the following two statements regarding the time of the first market entry.your business……… was driven by a market/economic opportunity ______ points… was driven by the necessity of doing a business ______ pointsPart 5: Thailand Perspectives

- 18.

- Does the Thailand Government support start-ups? O yes O noIf yes, how and in which stages? Any policy that you have recognized?

- 19.

- Does the country’s regulatory framework allow and facilitate individuals to run businesses? Please explain and provide examples.

- 20.

- How important have the technological/innovation advances in recent years been for your business? Why?

- 21.

- Do Thai people think and post a positive opinion about being an entrepreneur?

- 22.

- Do successful hospitality entrepreneurs appear in the media? Example?

References

- Aleksandrova, Ekaterina A., and Olga R. Verkhovskaya. 2016. Motivations to Start Businesses: Institutional Context. Working Paper No. 2 (E). Saint Petersburg: Graduate School of Management, St. Petersburg State University. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, Claudia, David Urbano, Alicia Coduras, and José Ruiz-Navarro. 2011. Environmental conditions and entrepreneurial activity: A regional comparison in Spain. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 18: 120–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabiyat, Talah S., Metri Mdanat, Mohamed Haffar, Ahmad Ghoneim, and Omar Arabiyat. 2019. The influence of institutional and conductive aspects on entrepreneurial innovation: Evidence from GEM data. Journal of Enterprise Information Management 32: 366–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyagari, Meghana, Thorsten Beck, and Asli Demirguc-Kunt. 2007. Small and medium enterprises across the globe. Small Business Economics 29: 415–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumol, William J., and Robert J. Strom. 2007. Entrepreneurship and economic growth. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 1: 233–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, Heiko, Mario Geissler, Christian Hundt, and Barbara Grave. 2018. The climate for entrepreneurship at higher education institutions. Research Policy 47: 700–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, Heiko, Susan Mueller, and Thomas Schrettle. 2014. The use of global entrepreneurship monitor data in academic research: A critical inventory and future potentials. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing 6: 242–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boettke, Peter, and Alexander Fink. 2011. Institutions first. Journal of Institutional Economics 7: 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosma, Niels, and Rebecca Harding. 2006. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor: GEM 2006 Summary Results. London: Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Consortium. [Google Scholar]

- Bruton, Garry D., David Ahlstrom, and Han-Lin Li. 2010. Institutional theory and entrepreneurship: Where are we now and where do we need to move in the future? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 34: 421–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busenitz, Lowell W., Carolina Gomez, and Jennifer W. Spencer. 2000. Country institutional profiles: Unlocking entrepreneurial phenomena. Academy of Management Journal 43: 994–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelleras, Joan-Lluis, Kevin F. Mole, Francis J. Greene, and David J. Storey. 2008. Do more heavily regulated economies have poorer performing new ventures? Evidence from Britain and Spain. Journal of International Business Studies 39: 688704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, John W., Vicki L. Plano Clark, Michelle L. Gutmann, and William E. Hanson. 2003. ADVANCED MIXED. In Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage, p. 209. [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq, Dirk, Dominic S. K. Lim, and Chang Hoon Oh. 2013. Individual–level resources and new business activity: The contingent role of institutional context. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 37: 303–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dheer, Ratan J. S. 2017. Cross-national differences in entrepreneurial activity: Role of culture and institutional factors. Small Business Economics 48: 813–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzingirai, Mufaro. 2021. Challenges to Necessity-Driven Nascent Entrepreneurship. In Handbook of Research on Nascent Entrepreneurship and Creating New Ventures. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 194–210. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Hui, Fevzi Okumus, Ke Wu, and Mehmet Ali Köseoglu. 2019. The entrepreneurship research in hospitality and tourism. International Journal of Hospitality Management 78: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentelsaz, Lucio, Juan P. Maicas, and Javier Montero. 2018. Entrepreneurs and innovation: The contingent role of institutional factors. International Small Business Journal 36: 686–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guion, Lisa A., David C. Diehl, and Debra McDonald. 2001. Conducting an In-Depth Interview. Gainesville: University of Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, EDIS. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, Lawrence E. 2008. The Central Liberal Truth: How Politics Can Change a Culture and Save It from Itself. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Henrekson, Magnus, and Tino Sanandaji. 2011. The interaction of entrepreneurship and institutions. Journal of Institutional Economics 7: 47–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessels, Jolanda, Marco Van Gelderen, and Roy Thurik. 2008. Entrepreneurial aspirations, motivations, and their drivers. Small Business Economics 31: 323–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, Geert. 2001. Culture’s recent consequences: Using dimension scores in theory and research. International Journal of Cross-Cultural Management 1: 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Hokyu, and Walter W. Powell. 2005. Institutions and entrepreneurship. In Handbook of Entrepreneurship Research. Boston: Springer, pp. 201–32. [Google Scholar]

- Junaid, Danish, Zheng He, Amit Yadav, and Lydia Asare-Kyire. 2019. Whether analogue countries exhibit similar women’s entrepreneurial activities? Management Decision 58: 759–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautonen, Teemu, Marco Van Gelderen, and Matthias Fink. 2015. Robustness of the theory of planned behavior in predicting entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 39: 655–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krungsri Research. 2021. Thailand Industry Outlook 2018–20: Hotel Industry. Available online: https://www.krungsri.com/en/research/industry/industry-outlook/services/hotels/io/io-hotel-21 (accessed on 24 April 2023).

- Kumar, Gunjan, and Saundarjya Borbora. 2016. Facilitation of entrepreneurship: The role of institutions and the institutional environment. South Asian Journal of Management 23: 57. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Sanghyeop, Kai-Sean Lee, Bee-Lia Chua, and Heesup Han. 2017. Independent café entrepreneurships in Klang valley, Malaysia. Challenges and critical factors for success: Does family matter? Journal of Destination Marketing and Management 6: 363–74. [Google Scholar]

- Levie, Jonathan, and Erkko Autio. 2008. A theoretical grounding and test of the GEM model. Small Business Economics 31: 235–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]