Towards the Voluntary Adoption of Integrated Reporting: Drivers, Barriers, and Practices

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. “Adoption” of Integrated Reporting

[1] improve the quality of information available to providers of financial capital to enable a more efficient and productive allocation of capital; [2] promote a more cohesive and efficient approach to corporate reporting that draws on different reporting strands and communicates the full range of factors that materially affect the ability to create value over time; [3] enhance accountability and stewardship for the broad base of capitals (financial, manufactured, intellectual, human, social and relationship, and natural) and promote understanding of their interdependencies; and [4] support integrated thinking, decision-making and actions that focus on the creation of value over the short, medium and long term.

2.2. Drivers, Barriers, and Practices to Adoption of Integrated Reporting

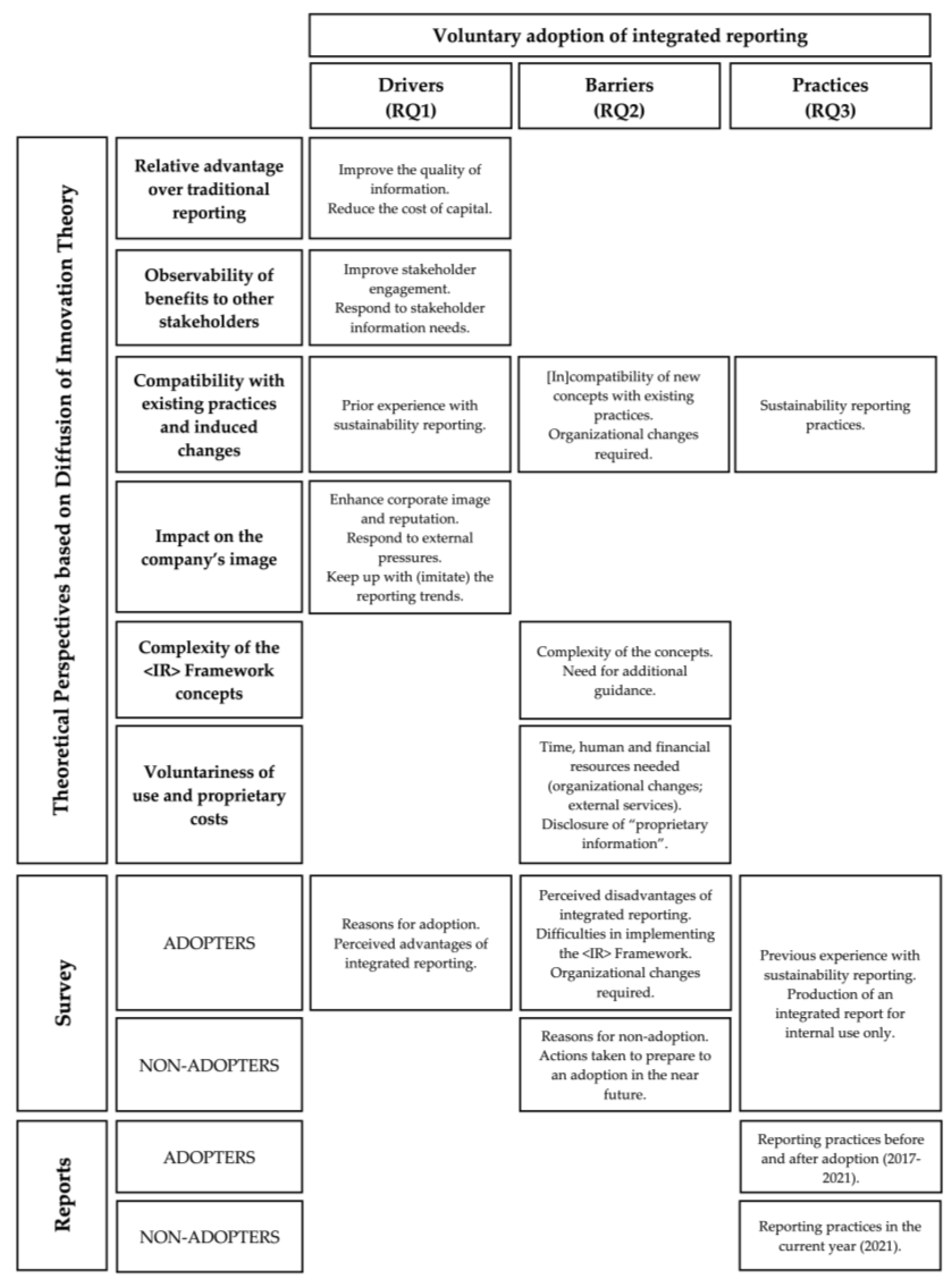

2.2.1. Theoretical Approach

- Relative advantage: the degree to which an innovation is perceived as being better than the idea it supersedes.

- Compatibility: the degree to which an innovation is perceived as consistent with the existing values, past experiences, and needs of potential adopters.

- Complexity: the degree to which an innovation is perceived as relatively difficult to understand and use.

- Trialability: the degree to which an innovation can be experimented with before it is adopted.

- Observability: the degree to which the results of an innovation are observable to others.

- Image: the degree to which use of an innovation is perceived to enhance one’s image or status.

- Voluntariness of use: the degree to which use of innovation is perceived as being voluntary or of free will.

- The perception that integrated reporting has a relative advantage over traditional reporting, particularly in improving the quality of information available to providers of financial capital.

- The observability of the benefits of integrated reporting, particularly to stakeholders other than providers of financial capital.

- The compatibility of integrated reporting with existing reporting practices and/or with existing internal procedures.

- The perceived impact on the company’s image or status of following the best practice and keeping up with its peers.

- The complexity of concepts in the <IR> framework, such as “connectivity”, and the [in]compatibility of new concepts such as “integrated thinking” with existing practices (“siloed” thinking).

- As it is a voluntary practice (voluntariness of use), it will only be adopted if the perceived benefits outweigh the costs.

2.2.2. Empirical Evidence

- Relative advantage over traditional reporting

- Observability of benefits to other stakeholders

- Compatibility with existing practices and induced changes

- Impact on the company’s image

- Complexity of the <IR> Framework concepts

- Voluntariness of use and proprietary costs

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Framework for the Analysis

3.2. Methods and Data

4. Results

4.1. Drivers for the Adoption of Integrated Reporting (RQ1)

4.2. Barriers to the Adoption of Integrated Reporting (RQ2)

4.3. Reporting Practices towards the Adoption of Integrated Reporting (RQ3)

4.3.1. The Reporting Practices of “Adopters”

4.3.2. The Reporting Practices of “Non-Adopters”

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adhariani, Desi, and Charl de Villiers. 2019. Integrated reporting: Perspectives of corporate report preparers and other stakeholders. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 10: 126–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, Mitali P., Sumit Lodhia, and Gerard W. Stone. 2021. Preparers’ perceptions of integrated reporting: A global study of integrated reporting adopters. Accounting and Finance 62: 1381–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, Mitali P., Sumit Lodhia, and Gerard W. Stone. 2022. Enablers and barriers to the involvement of accountants in integrated reporting. Meditari Accountancy Research 30: 676–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baboukardos, Diogenis, and Gunnar Rimmel. 2016. Value relevance of accounting information under an integrated reporting approach: A research note. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 35: 437–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bananuka, Juma, Zainabu Tumwebaze, and Laura Orobia. 2019. The adoption of integrated reporting: A developing country perspective. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting 17: 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, Mary E., Steven F. Cahan, Li Chen, and Elmar R. Venter. 2017. The economic consequences associated with integrated report quality: Capital market and real effects. Accounting, Organizations and Society 62: 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, Cristiana, and Andrew W. Stark. 2018. Environmental, social and governance disclosure, integrated reporting, and the accuracy of analyst forecasts. The British Accounting Review 50: 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, Jenna J., and Cynthia E. Clark. 2016. The business case for integrated reporting: Insights from leading practitioners, regulators, and academics. Business Horizons 59: 273–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carels, Candice, Warren Maroun, and Nirupa Padia. 2013. Integrated reporting in the South African mining sector. Corporate Ownership & Control 11: 957–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo, Cecília, and Cristiana Ribeiro. 2022. Mandatory non-financial information disclosure under European Directive 95/2014/EU: Evidence from Portuguese listed companies. Sustainability 14: 4860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaidali, Panagioula, and Michael J. Jones. 2017. It’s a matter of trust: Exploring the perceptions of Integrated Reporting preparers. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 48: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CMVM. 2021. Modelo de relatório para divulgação de informação não financeira pelas sociedades emitentes de valores mobiliários admitidos à negociação em mercado regulamentado. Available online: https://www.cmvm.pt/pt/Legislacao/ConsultasPublicas/CMVM/Documents/Modelo%20de%20Informa%C3%A7%C3%A3o%20N%C3%A3o%20Financeira.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Connelly, Brian L., S. Trevis Certo, R. Duane Ireland, and Christopher R. Reutzel. 2011. Signaling theory: A review and assessment. Journal of Management 37: 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Graaff, Brigitte, and Bert Steens. 2023. Integrated reporting: Exploring supervisory board members’ perspectives on the motives, drivers and benefits. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change 19: 191–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Villiers, Charl, and Pei-Chi K. Hsiao. 2018. Integrated Reporting. In Sustainability Accounting and Integrated Reporting. Edited by Charl de Villiers and Warren Maroun. London: Routledge, pp. 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- de Villiers, Charl, Leonardo Rinaldi, and Jeffrey Unerman. 2014. Integrated reporting: Insights, gaps and an agenda for future research. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 27: 1042–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, Colin, and John Burns. 2010. Integrated reporting at Novo Nordisk. In Accounting for Sustainability: Practical Insights. Edited by Anthony Hopwood, Jeffrey Unerman and Jessica Fries. London: Routledge, pp. 215–32. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, Douglas W., and Robert E. Verrecchia. 1991. Disclosure, liquidity, and the cost of capital. The Journal of Finance 46: 1325–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragu, Ioana-Maria, and Adriana Tiron-Tudor. 2013. The Integrated Reporting Initiative from an Institutional Perspective: Emergent Factors. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences 92: 275–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumay, John, and Tim Dai. 2017. Integrated thinking as a cultural control? Meditari Accountancy Research 25: 574–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumay, John, Cristiana Bernardi, James Guthrie, and Matteo La Torre. 2017. Barriers to implementing the International Integrated Reporting Framework: A contemporary academic perspective. Meditari Accountancy Research 25: 461–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, Ronald A. 1985. Disclosure of nonproprietary information. Journal of Accounting Research 23: 123–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, Robert G., and Michael P. Krzus. 2010. One Report: Integrated Reporting for a Sustainable Strategy. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Farneti, Federica, Federica Casonato, Monica Montecalvo, and Charl de Villiers. 2019. The influence of integrated reporting and stakeholder information needs on the disclosure of social information in a state-owned enterprise. Meditari Accountancy Research 27: 556–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, Ruhama B., and Alexandro Barbosa. 2022. Factors associated with the voluntary disclosure of the integrated report in Brazil. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting 20: 446–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiori, Giovanni, Francesca di Donato, and Maria F. Izzo. 2016. Exploring the effects of corporate governance on voluntary disclosure: An explanatory study on the adoption of integrated report. In Performance Measurement and Management Control: Contemporary Issues. Edited by Marc J. Epstein, Frank Verbeeten and Sally K. Windener. Bradford: Emerald Group Publishing, pp. 83–108. [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrmann, Stephan. 2019. A multi-theoretical approach on drivers of integrated reporting: Uniting firm-level and country-level associations. Meditari Accountancy Research 28: 168–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, Isabel-María, and Ligia Noguera-Gámez. 2017a. Integrated information and the cost of capital. International Business Review 26: 959–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, Isabel-María, and Ligia Noguera-Gámez. 2017b. Integrated reporting and stakeholder engagement: The effect on information asymmetry. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 24: 395–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, Isabel-Maria, Nicola Raimo, and Filippo Vitolla. 2021. CEO power and integrated reporting. Meditari Accountancy Research 29: 908–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibassier, Delphine, Michelle Rodrigue, and Diane-Laure Arjaliès. 2018. Integrated reporting is like God: No one has met Him, but everybody talks about Him. The power of myths in the adoption of management innovations. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 31: 1349–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girella, Laura, Paola Rossi, and Stefano Zambon. 2019. Exploring the firm and country determinants of the voluntary adoption of integrated reporting. Business Strategy and the Environment 28: 1323–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girella, Laura, Stefano Zambon, and Paola Rossi. 2022. Board characteristics and the choice between sustainability and integrated reporting: A European analysis. Meditari Accountancy Research 30: 562–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunarathne, Nuwan, and Samanthi Senaratne. 2017. Diffusion of integrated reporting in an emerging South Asian (SAARC) nation. Managerial Auditing Journal 32: 524–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haji, Abdifatah A., and Mutalib Anifowose. 2016. The trend of integrated reporting practice in South Africa: Ceremonial or substantive? Sustainability 7: 190–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IIRC. 2011. Towards Integrated Reporting: Communicating Value in the 21st Century. IIRC. Available online: https://www.integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/IR-Discussion-Paper-2011_spreads.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- IIRC. 2012a. Towards Integrated Reporting: Communicating Value in the 21st Century: Summary of Responses to the September 2011 Discussion Paper and Next Steps. IIRC. Available online: https://www.integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/Discussion-Paper-Summary1.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- IIRC. 2012b. Draft Framework Outline. IIRC. Available online: https://www.integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/Draft-Framework-Outline.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- IIRC. 2012c. Capturing the Experiences of Global Businesses and Investors—The Pilot Programme 2012 Yearbook. IIRC. Available online: https://www.integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/THE-PILOT-PROGRAMME-2012-YEARBOOK.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- IIRC. 2013a. Business and Investors Explore the Sustainability Perspective of Integrated Reporting—IIRC Pilot Programme 2013 Yearbook. IIRC. Available online: https://www.integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/IIRC-PP-Yearbook-2013.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- IIRC. 2013b. The International <IR> Framework. Available online: https://www.integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/13-12-08-THE-INTERNATIONAL-IR-FRAMEWORK-2-1.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- IIRC. 2021. International <IR> Framework. Available online: https://www.integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/InternationalIntegratedReportingFramework.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Kannenberg, Linda, and Philipp Schreck. 2019. Integrated reporting: Boon or bane? A review of empirical research on its determinants and implications. Journal of Business Economics 89: 515–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıç, Merve, Ali Uyar, Cemil Kuzey, and Abdullah S. Karaman. 2021. Does institutional theory explain integrated reporting adoption of Fortune 500 companies? Journal of Applied Accounting Research 22: 114–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Oliver, and Robert E. Verrecchia. 1994. Market liquidity and volume around earnings announcements. Journal of Accounting and Economics 17: 41–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, Alexander, Janina Rochell, Christian Klein, and Bernhard Zwergel. 2020. Integrated reporting of environmental, social, and governance and financial data: Does the market value integrated reports? Business Strategy and the Environment 29: 1750–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, Ana I., and Daniela Penela. 2022. From little seeds to a big tree: A far-reaching assessment of the integrated reporting stream. Meditari Accountancy Research 30: 1514–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNally, Mary-Anne, Dannielle Cerbone, and Warren Maroun. 2017. Exploring the challenges of preparing an integrated report. Meditari Accountancy Research 25: 481–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, Nandita, Mohamed Nurullah, and Adel Sarea. 2022. An empirical study on company’s perception of integrated reporting in India. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting 20: 493–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Gary C., and Izak Benbasat. 1991. Development of an instrument to measure the perceptions of adopting an information technology innovation. Information Systems Research 2: 192–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete-Oyarce, José, Juan A. Gallegos, Hugo Moraga-Flores, and José L. Gallizo. 2021. Integrated Reporting as an academic research concept in the area of business. Sustainability 13: 7741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishitani, Kimitaka, Jeffrey Unerman, and Katsuhiko Kokubu. 2021. Motivations for voluntary corporate adoption of integrated reporting: A novel context for comparing voluntary disclosure and legitimacy theory. Journal of Cleaner Production 322: 129027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwachukwu, Chijioke. 2021. Systematic review of integrated reporting: Recent trend and future research agenda. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting 20: 580–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktorina, Megawati, Sylvia V. Siregar, Desi Adhariani, and Aria F. Mita. 2022. The diffusion and adoption of integrated reporting: A cross-country analysis on the determinants. Meditari Accountancy Research 30: 39–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permatasari, Ika, and I. Made Narsa. 2022. Sustainability reporting or integrated reporting: Which one is valuable for investors? Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change 18: 666–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, Fiona A., and Martin Samy. 2015. Factors affecting the diffusion of integrated reporting: A UK FTSE 100 perspective. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 6: 190–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, Fiona A., and Martin Samy. 2020. Rationales for integrated reporting adoption and factors impacting on the extent of adoption: A UK perspective. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 11: 351–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, Pablo, Carmen Correa, and Carlos Larrinaga. 2019. Is integrated reporting transformative? An exploratory study of non-financial reporting archetypes. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 10: 617–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, Everett M. 1983. Diffusion of Innovation, 3rd ed. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, Adriana, and Mercedes Luque-Vílchez. 2021. The implementation of sustainability reporting in a small and medium enterprise and the emergence of integrated thinking. Meditari Accountancy Research 29: 966–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriya, Sushila, and Parthvi Rastogi. 2021. A systematic literature review on integrated reporting from 2011 to 2020. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting 20: 558–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, Michael. 1973. Job Market Signaling. Quartely Journal of Economics 87: 355–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyn, Maxi. 2014. Organisational benefits and implementation challenges of mandatory integrated reporting: Perspectives of senior executives at South African listed companies. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 5: 476–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velte, Patrick. 2021. Archival research on integrated reporting: A systematic review of main drivers and the impact of integrated reporting on firm value. Journal of Management and Governance 26: 997–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velte, Patrick, and Martin Stawinoga. 2017. Integrated reporting: The current state of empirical research, limitations and future research implications. Journal of Management Control 28: 275–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veltri, Stefania, and Antonella Silvestri. 2015. The Free State University integrated reporting: A critical consideration. Journal of Intellectual Capital 16: 443–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veltri, Stefania, and Antonella Silvestri. 2020. The value relevance of corporate financial and nonfinancial information provided by the integrated report: A systematic review. Business Strategy and the Environment 29: 3038–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrecchia, Robert E. 1983. Discretionary disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Economics 5: 179–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitolla, Filippo, and Nicola Raimo. 2018. Adoption of integrated reporting: Reasons and benefits—A case study analysis. International Journal of Business and Management 13: 244–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, Annika, Michel Charifzadeh, and Fabian Diefenbach. 2020. Voluntary adopters of integrated reporting: Evidence on forecast accuracy and firm value. Business Strategy and the Environment 29: 2542–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Shan, Roger Simnett, and Wendy Green. 2017. Does integrated reporting matter to the capital market? Abacus 53: 94–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| “Adopters” | “Non-Adopters” | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 4 companies | 40 companies | 44 |

| Surveys answered | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Reports analyzed | 4 companies (2017–2021) | 40 companies (2021) |

| Company 1 | Company 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Position of the respondent | Sustainability Officer | Investor Relations Officer |

| Department responsible for the preparation of the integrated report | Shared responsibility for the departments of: Planning and Control, Accounting and Finance, and Sustainability. | Investor Relations Department |

| Company 3 | Company 4 | Company 5 | Company 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position of the respondent | Chief Financial Officer | Director of the investor relations department | Director of the reporting department and investor relations | Group accounting manager |

| What Was the Reason for Your Company to Publish an Integrated Report According to the <IR> Framework? | ||

|---|---|---|

| Company 1 | Company 2 | |

| The company was required by a certain entity to do so. (If possible, please mention the entity in the comment box) | √ | |

| Because it is good for the company’s image to keep up with the latest reporting trends. | ||

| To follow the reporting practices of other companies. (If possible, please mention in the comment box if they were competing companies, companies from the same sector and/or the same stock exchange) | √ | |

| Because integrated reporting provides more relevant information compared to traditional reporting. | ||

| Another reason. Which one? | ||

| Please Indicate Your Degree of Agreement/Disagreement Regarding the Advantages for Your Company of Publishing an Integrated Report According to the <IR> Framework. Scale: 1—Strongly Disagree; 2—Disagree; 3—No Opinion; 4—Agree; 5—Strongly Agree | ||

|---|---|---|

| Company 1 | Company 2 | |

| It allows a better identification of the “capitals”. | Strongly agree | Agree |

| It improves the company’s image. | Agree | |

| It improves the conditions for access to bank financing. | Agree | |

| It allows for better risk identification and management. | Agree | |

| It allows for better capital management and the creation of more value. | Agree | |

| It allows for attracting new customers. | Agree | Disagree |

| It allows access to new suppliers. | ||

| It increases stock liquidity and reduces the cost of equity capital. | No opinion | |

| It allows the disclosure of information about intellectual capital not presented in the financial statements. | No opinion | Agree |

| What Organizational Changes Have Taken Place to Start Preparing and Publishing the Integrated Report According to the <IR> Framework? | ||

|---|---|---|

| Company 1 | Company 2 | |

| Creation of a specific department. Which department? | ||

| Creation of a specific committee in the governance structure. Which committee? | √ | |

| Hiring more employees. For which functions? | ||

| Acquisition of technological resources. Which ones? | √ “Platform for publishing the report” | √ |

| Outsourcing services. Which ones? | √ “Support for structuring the Integrated Report in the first year.” | √ |

| Other changes. Please indicate which. | ||

| No organizational changes were needed. | ||

| The IIRC Structure for Integrated Reporting Mentions a Set of Principles and Concepts. Please Indicate Your Opinion Regarding the Difficulty of Implementing These Principles/Concepts. Scale: 1—Very Easy; 2—Easy; 3—No Opinion; 4—Difficult; 5—Very Difficult. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Company 1 | Company 2 | |

| Strategic focus and future orientation | Difficult | Easy |

| Connectivity of information | Easy | Difficult |

| Stakeholder relationships | Easy | |

| Materiality | Difficult | |

| Conciseness | Difficult | Very Difficult |

| Reliability and completeness | Easy | |

| Consistency and comparability | Easy | |

| Value creation | Easy | No opinion |

| The capitals (financial, manufactured, natural, intellectual, human, social, and relationship) | Easy | No opinion |

| Please Indicate Your Degree of Agreement/Disagreement Regarding the Disadvantages for Your Company of Publishing an Integrated Report According to the <IR> Framework. Scale: 1—Strongly Disagree; 2—Disagree; 3—No Opinion; 4—Agree; 5—Strongly Agree | ||

|---|---|---|

| Company 1 | Company 2 | |

| The transition from traditional reporting to integrated reporting is very costly. | Disagree | Strongly agree |

| Integrated reporting is more expensive than traditional reporting even after the transition. | Strongly disagree | Agree |

| Integrated reporting exposes aspects of the company’s strategy to competitors. | ||

| Integrated reporting makes the risks to which the company is subject more visible, compared with traditional reporting. | Disagree | Agree |

| What Are the Reasons Why Your Company Has Not Yet Started the Process towards the Publication of the Integrated Report According to the <IR> Framework? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Company 3 | Company 4 | Company 5 | Company 6 | |

| Integrated reporting relies on concepts that are difficult to implement. | ||||

| The transition from traditional to integrated reporting is very costly. | √ | √ | ||

| Integrated reporting is more expensive than traditional reporting even after the transition. | √ | |||

| Integrated reporting exposes aspects of the company’s strategy to competitors. | ||||

| Integrated reporting makes the risks to which the company is subject more visible, compared with traditional reporting. | ||||

| The company does not consider any advantages or disadvantages as long as integrated reporting is not mandatory. | √ | |||

| Other reasons. Which ones? | √ | √ | ||

| Company | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | CTT | GALP | SONAE | NOS |

| 2017 | MR&FS + CGR + SR | IR | MR&FS + CGR + SR | UR |

| 2018 | IR | IR | UR | UR |

| 2019 | IR | IR | UR | UR |

| 2020 | IR | IR | IR | UR |

| 2021 | IR | IR | IR | IR |

| Company | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | CTT | GALP | SONAE | NOS |

| 2017 | SDG, CDP | IIRC, GRI, UNGC, SDG, EITI, TCFD | GRI, UNGC, SDG | GRI, UNGC, SDG |

| 2018 | IIRC, GRI, SGD, CDP | IIRC, GRI, UNGC, SGD, TCFD | GRI, UNGC, SGD | GRI, UNGC, SGD |

| 2019 | IIRC, GRI, SGD, CDP | IIRC, GRI, UNGC, SGD, TCFD | GRI, UNGC, SGD | GRI, UNGC, SGD |

| 2020 | IIRC, GRI, SGD, CDP | IIRC, GRI, UNGC, SGD, TCFD, SASB, WORLD ECONOMIC FORUM | IIRC, GRI, UNGC, SGD | GRI, UNGC, SGD |

| 2021 | IIRC, GRI, SGD, CDP CMVM | IIRC, GRI, UNGC, SGD, TCFD, SASB, WORLD ECONOMIC FORUM CMVM | IIRC, GRI, UNGC, SGD, TCFD | IIRC, GRI, UNGC, SGD, TCFD |

| Year | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Company | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

| CTT | Limited Assurance | Limited Assurance | |||

| ISAE 3000 | ISAE 3000 | ||||

| KPMG | KPMG | EY | |||

| GALP | Reasonable assurance on the Carbon Footprint. Limited Assurance on the remaining non-financial information | ||||

| ISAE 3000 | |||||

| PWC | |||||

| SONAE | External verification | Limited Assurance | Limited Assurance | ||

| - | ISAE 3000 | ISAE 3000 | |||

| EY | KPMG | KPMG | |||

| NOS | Limited Assurance | Limited Assurance | |||

| ISAE 3000 | ISAE 3000 | ||||

| EY | EY | ||||

| N. of Companies | Corporate Reports | Frameworks Applied | Assurance Provided | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | 2 | UR | GRI, SASB, TCFD, UNGC, WORLD ECNOMIC FORUM, SGD, CDP | Limited Assurance ISAE 3000 EY, PWC |

| Group 2 | 3 | MR&FS + SR MR&FS + CGR + SR | GRI, TCFD, WORLD ECONOMIC FORUM, SGD, CMVM | Limited Assurance ISAE 3000 PWC, KPMG |

| Group 3 | 15 | MR&FS MR&FS + CGR + SR UR | GRI, SASB, TCFD, UNGC, WORLD ECONOMIC FORUM, SGD, CMVM | - |

| Group 4 | 20 | MR&FS MR&FS + CGR MR&FS + CGR + SRR | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carmo, C.; Correia, I.; Leite, J.; Carvalho, A. Towards the Voluntary Adoption of Integrated Reporting: Drivers, Barriers, and Practices. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13060148

Carmo C, Correia I, Leite J, Carvalho A. Towards the Voluntary Adoption of Integrated Reporting: Drivers, Barriers, and Practices. Administrative Sciences. 2023; 13(6):148. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13060148

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarmo, Cecília, Inês Correia, Joaquim Leite, and Amélia Carvalho. 2023. "Towards the Voluntary Adoption of Integrated Reporting: Drivers, Barriers, and Practices" Administrative Sciences 13, no. 6: 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13060148

APA StyleCarmo, C., Correia, I., Leite, J., & Carvalho, A. (2023). Towards the Voluntary Adoption of Integrated Reporting: Drivers, Barriers, and Practices. Administrative Sciences, 13(6), 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13060148