Abstract

This paper aims to assess workers’ well-being through a survey of Italian firms by exploring the factors of leadership styles, ethical behavior, and organizational identification. In recent years, also due to the COVID-19 pandemic and technological progress, workers’ well-being has increasingly become a fundamental driver for company strategy and governance. Workers are increasingly interested in their well-being and work–life balance rather than just their level of remuneration or position at work. The company’s ability to strategically retain capable collaborators is, therefore, fundamental, especially in light of the recent increase in resignations. Based on a sample of workers in Italian firms during the post-COVID-19 period (the year 2022), this paper evaluates whether leadership styles, ethical behavior, and organizational identification are related to workers’ well-being beyond the workplace. The empirical model allows for a clear and effective evaluation of several characteristics, enabling a more comprehensive understanding of the data that support management’s strategic decisions regarding worker well-being policies.

1. Introduction

The term “well-being” is widely used in modern society, as it has always been important for the physical and psychological evolution of humanity. Well-being is generally linked to a satisfying quality of life, and it is considered crucial to reach happiness and health. The issue of well-being is important in various fields of research and applications. In recent years, well-being has often been associated with job topics and, in particular, with the organization and management of firms. Indeed, people spend a lot of their time at work, and undoubtedly, work-related issues can affect the overall level of well-being of individuals. A workplace that prioritizes worker well-being provides employees with a supportive environment that promotes good health, happiness, and success. Hence, emphasizing worker well-being benefits both employees and companies, as it leads to a happier and more productive workforce, which contributes to the company’s overall success and growth (Tortia 2008; Zhang et al. 2022; Moreira et al. 2023). Moreover, companies that promote well-being have a better chance of preserving their employees so as to retain the best collaborators and fight against the recent phenomenon of the so-called Great Resignation (Tessema et al. 2022; Serenko 2023). Managers should consider how to use available human capital to preserve and improve the well-being of the workers. The well-being of workers has implications for society, families, and even the productivity of firms.

Hence, some recent studies have highlighted the need to look deeper into the well-being of workers in firms in light of important transformations during the pandemic period and technological progress. The COVID-19 pandemic has played a significant role in the level of workers’ well-being, not only out of fear of exposure to the virus but especially about the concerns of financial insecurities, as well as the increased level of anxiety and stress (Foti et al. 2023). The pandemic period changed people’s way of working and work habits, which had significant impacts on job satisfaction, well-being, and work–life balance. For example, the policy regulations related to the containment of the COVID-19 virus have introduced a wide range of measures to incentivize and—in many cases—mandate a temporary shift to working from home. Remote working has also had significant importance in the current post-COVID-19 emergency period, posing necessary reflections on the new drivers of worker well-being. Hence, an important topic is a blurred boundary between the start and end of the workday (Fan and Moen 2022). Moreover, work settings and digital equipment are, in many cases, inadequate with at-home workstation adjustment costs initially borne by employees themselves (Rudnicka et al. 2020). The linkages between workers’ well-being and technological progress have a twofold direction. Indeed, technological progress can improve productivity, ensuring higher wages and higher possibilities of job retention. However, technological progress and automation, such as artificial intelligence, for example, can negatively impact well-being through the increase of stress and insecurities in job perspectives. The positive or negative consequences depending on how technological progress is applied and managed (Johnson et al. 2020; Nazareno and Schiff 2021).

To promote workers’ well-being, and in light of recent social transformations, several authors have studied certain managerial aspects within companies, such as organizational identification, ethical behavior, and leadership styles. Recent studies have highlighted the role of leadership style on employees’ well-being, considering that different leadership styles (e.g., autocratic, participative, laissez-faire) affect the workers’ psychological well-being differently. Hence, corporate governance should consider the best leadership style to increase workers’ well-being (Scheidlinger 1994; Avolio et al. 2009; Bass and Riggio 2006; Bryman 2013; Inceoglu et al. 2018). Organizational identification refers to the extent to which individuals feel a sense of attachment and commitment to the organization they work for. When individuals identify with an organization, they see themselves as part of it and perceive the goals, values, and interests of the organization as their own (Wiesenfeld et al. 2001; Riketta 2005; Sillince and Golant 2018). Workers with high organizational identification could have higher job satisfaction and lower levels of stress, with a positive effect in terms of well-being and work–life balance (Knight and Haslam 2010; Conroy et al. 2017; Greco et al. 2022; Andrade and Neves 2022; Garraio et al. 2023). Some recent research has suggested that an ethical climate and positive working environment could be another important driver to improve workers’ well-being. The ethical climate could be associated with a perception of trust toward colleagues and corporate governance. The greater feeling of trust could reduce the levels of stress and anxiety, with positive implications on productivity and motivation (Victor and Cullen 1988; Briggs et al. 2012; Teresi et al. 2019; Su and Hahn 2022). However, the direct connection between leadership styles, ethical climate, organizational identification, and workers’ mental well-being beyond the workplace remains understudied in recent literature, as these items have been explored mostly in terms of their impact on job performance and well-being in relation to the working environment. It is worth considering that working hours take up a large part of the day and, therefore, company dynamics can have an impact on the general mental well-being of workers outside the working context.

To the best of our knowledge, there are no conclusive results about these aspects related to workers’ well-being, and no previous studies have investigated whether these factors together contribute to better workers’ mental well-being beyond the workplace. In addition, a recent study examined whether COVID-19 could play a role in facilitating or constraining these patterns (Foti et al. 2023). Thus, we extend our main analysis by investigating the influence of leadership style, organizational identification, and ethical climate together on workers’ well-being (the so-called WHO-5 Well-Being Index) beyond the workplace in the post-COVID-19 emergency period. The study allowed us to map these variables across two medium–large-sized Italian companies also with offices abroad. In total, 390 responsive workers were surveyed in the year 2022 through a self-administered questionnaire developed on the Qualtrics Platform.

There are several motivations at the basis of the analysis. It is an under-researched issue, but relevant for the management and success of companies, above all, to avoid the resignation of good collaborators. This study applies a suitable methodology with an application of a structured questionnaire survey and econometric analysis. Moreover, the focus on general well-being outside the firms contributes to the managerial literature about the suitable drivers to be used; it has interesting implications for future research, as well as useful applications of managerial practices and social implications, allowing a more comprehensive understanding of the data that support managements’ strategic decisions regarding worker well-being policies. The main results of the empirical analysis identified that workers’ general well-being was positively associated with organizational identification, the ethical friendship climate, and the participative style of leadership. Otherwise, the job stressor index seems to be negatively related to general workers’ well-being. These results can support the strategic choices of management in policies toward workers’ well-being to retain capable collaborators and prevent potentially expensive resignations.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 specifically presents the theoretical approach and hypothesis; Section 3 describes the research design and the methodology followed; Section 4 presents the results. Section 5 provides the discussion and implications, and Section 6 offers the conclusions, limitations, and future research directions.

2. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Theoretical Background

Well-being is a very important issue for the workers, as well as for the success of the companies. The interest in well-being can be traced back thousands of years, and it has always been very important to people’s lives. It refers to an overall state of psychological and physical satisfaction experienced by individuals. It describes personal traits that establish how an individual reacts in circumstances of pressure, stress, and opportunities. Recently, the concept of well-being has received significant attention in the fields of management and psychology (Yadeun-Antuñano 2019).

The conceptualization of well-being has been addressed mainly through the objective approach and the subjective approach (Brown et al. 2012; Knox et al. 2015). The objective well-being approach relates to observable and quantifiable data as social, physical, and economic indicators. Policymakers, academics, and companies often use objective measures to compare an individual’s or population’s well-being. In the objective approach, workers’ well-being is measured based on whether the job contributes to satisfying their needs and achieving their goals (Budd and Spencer 2015). Therefore, the objective approach depends on ”job quality” measures, i.e., job features and working conditions (Felstead et al. 2019; Howell and Kalleberg 2019). The objective approach has also been criticized for focusing on the characteristics of the job and for ignoring the wider meanings that work has in people’s lives (Nikolova and Cnossen 2020).

The subjective well-being approach admits that individuals’ well-being cannot be completely assessed only through objective or external indicators. Subjective well-being emphasizes the crucial role of an individual’s own perspectives in defining their general well-being by assuming that people are the best judge of their work and satisfaction. Indeed, the most important measure of subjective well-being is job satisfaction (Stone and Mackie 2014; Graham et al. 2018). A critical aspect of job satisfaction as a proxy of worker well-being is that workers may feel satisfied in an objectively bad job (Brown et al. 2012). Well-being can be considered from different points of view, and it can be influenced by several drivers of the company organization.

It is worth considering that working hours absorb a large part of the day. The time spent at work seems to be a crucial component of people’s utility and subjective well-being. Therefore, company dynamics can also have an impact on the general mental well-being of workers outside the working context (Bryson and MacKerron 2017). Research has indicated that work contributes to overall satisfaction (Blanchflower and Oswald 2011). In this framework, global changes, digital transformation, and technological progress are modifying some drivers of well-being so as to question some managerial and organizational theories. In recent years, workers’ well-being has been assessed with great interest, and many studies have attempted to investigate it further. It is crucial for companies and managers to recognize the main drivers of overall well-being and to identify the elements to improve workers’ lives according to the economic successes of the companies.

Hence, while the WHO-5 questionnaire primarily focuses on assessing only mental well-being at an individual level in several psychological and clinical topics (Topp et al. 2015; Cosma et al. 2022), it can also be applied in the context of management studies to measure workers’ well-being in organizations and beyond the workplace. In this context, the theoretical framework of mental workers’ well-being, as captured by the WHO-5, can draw from various management and organizational behavior theories that are worth exploring.

2.2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

A systematic analysis of the recent literature allowed us to recognize the main areas of research interest in management and psychological studies about workers’ well-being. We obtained the following main topics: job stressors, organizational identification, leadership style, and ethical climate.

Recent studies have suggested that job stress may be associated with negative health and mental well-being outcomes (Karasek 1979). For example, Tyssen et al. (2000) found evidence that job stress is a risk factor for poor mental well-being among working adults in Norway. Law et al. (2020) also indicated a strong relationship between job stress and the poor mental health of young workers. The relationship between job stress and negative mental well-being is well established. Hence, the literature has shown that high levels of stress at work can lead to psychological consequences in overall well-being (Mensah 2021). The stress associated with carrying out a professional activity was often underestimated. Stress was considered physiological both by the workers themselves and by the employers. Recently, however, there has been more talk of so-called burnout syndrome (Schaufeli and Bakker 2004). On the basis of the most recent studies conducted, we hypothesized, therefore, that the level of job stressors is associated with workers’ overall mental well-being.

H1.

Job stressors will be associated with a worse level of mental well-being, according to WHO-5.

Recent studies have highlighted how management can direct some organizational variables to improve worker satisfaction and well-being. Organizational identification, leadership style, and ethical climate seem to be the most important drivers on this topic.

Organizational identification is defined as the process through which individuals develop a connection with the organization for which they are working (Ashforth and Mael 1989). This connection is not merely a cognitive process of recognizing membership in an organization but also involves an emotional bond and dedication toward the organization (Pratt 1998). Recent literature has shown how highly “identified” individuals also commonly (although not indisputably; see Conroy et al. 2017 for a review) report higher levels of a number of outcomes in the workplace, such as higher job satisfaction, lower work-related stress and lower turnover intentions (Wegge et al. 2006; Lee et al. 2015).

In addition, two recent meta-analyses (Steffens et al. 2017; Greco et al. 2022) have highlighted the positive effects of organizational identification on individuals’ overall well-being and health. The findings of Steffens et al. (2017) revealed a strong positive association between organizational identification and health, particularly in relation to well-being and psychological health (rather than stress and physical health). The meta-analysis by Greco et al. (2022) also confirms how organizational identification has an impact, especially on certain aspects of individual well-being: in particular, out of the five sub-components considered (self-esteem, psychological well-being, engagement, stress, and burnout), this effect is most noticeable on self-esteem and psychological well-being. Similarly, other recent studies confirmed that organizational identification has a positive impact not only on work-related variables but also on overall personal well-being, intended as self-esteem, satisfaction with life, and self-efficacy (Harris and Cameron 2005), psychological well-being (Hameed et al. 2022), enhanced happiness and reduced stress (De Giorgio et al. 2023). However, the specific effects of organizational identification on individual mental well-being are as yet mostly unexplored. These findings led us to hypothesize a positive association between organizational identification and workers’ mental well-being.

H2.

Organizational identification will be associated with a higher level of mental well-being, according to WHO-5.

Leadership is a crucial concept in organizational behavior that has garnered significant attention in the past few decades. Scholars define leadership as the process of influencing others to contribute toward attaining group goals (Haslam 2004). Consequently, leadership has become the subject of intense investigation as it is closely tied to organizational success. Scholars have distinguished between various “leadership styles”, sets of behaviors employed by leaders to influence subordinates’ conduct (Bass and Riggio 2006), which have become important points of discussion in leadership research (Judge et al. 2002; Judge and Piccolo 2004; Brown et al. 2005). The present study examined the primary leadership styles identified by Lewin et al. (1939) and revisited by Scheidlinger (1994), namely authoritative (or autocratic), democratic (or participative), and laissez-faire (or ‘let it be’). Authoritative leadership is based on the leader’s ability to direct and control their subordinates. The leader sets clear goals for their subordinates and provides them with a sense of autonomy and empowerment (Bass and Riggio 2006). Democratic leadership is based on the idea that collaboration and teamwork can lead to more effective decision-making (Gastil 1994). The leader invites subordinates to participate in the decision-making process and values their ideas and opinions. Democratic leadership is associated with open communication, shared decision-making, and a focus on building relationships and trust among team members (Avolio et al. 2009). Laissez-faire leadership is a hands-off approach in which the leader provides little direction or guidance to their subordinates. Instead, subordinates are given complete autonomy and responsibility for their work. Laissez-faire leadership is often associated with an “avoidance or absence of leadership” (Judge and Piccolo 2004), which emphasizes the importance of autonomy within an organization (Bryman 2013).

Previous literature has extensively explored the association between managerial leadership and employees’ well-being. Numerous studies have highlighted how leadership styles based on control are linked with poor job well-being and psychological health among employees (Nyberg 2009; Kuoppala et al. 2008; Inceoglu et al. 2018). A study conducted by Anna Nyberg (2009) showed, in particular, that autocratic and self-centered leadership styles are related to poor employee mental health, vitality, and increased behavioral stress. Furthermore, laissez-faire leadership has also been linked to employee psychological distress, although its relation varies widely depending on the organization’s structure and personnel skills (Skogstad et al. 2007). Indeed, the effects of laissez-faire leadership on distress can be mediated by the occurrence of specific workplace stressors, such as exposure to workplace bullying.

On the other hand, participative management styles have been found to be associated with higher levels of satisfaction at work (Kim 2002) and employee engagement (Chan 2019). However, as pointed out in the meta-analysis by Inceoglu et al. (2018), the majority of the literature investigating leadership and well-being has mostly focused on transformational and transactional leadership styles, as defined by Bass (1985) and has taken into account elements of well-being strictly related to the work context, such as job satisfaction (Hobman et al. 2011; Bhatti et al. 2012; Braun et al. 2013). The direct connection between autocratic, participative, and laissez-faire leadership and employees’ overall well-being beyond the workplace, on the other hand, remains understudied in recent literature, as these leadership styles have been explored mostly in terms of their impact on job performance (Huang et al. 2010; Ahmed Iqbal et al. 2021). These findings led us to hypothesize a different association between different leadership styles and workers’ mental well-being.

H3.

The effects on workers’ mental well-being according to WHO-5 vary across the different leadership styles.

The ethical climate was defined by Victor and Cullen (1988) as a set of shared perceptions of organizational conventions, norms, and procedures that can be either informal or codified (through formalized regulations and policies). Ethical work climates shape workers’ perceptions and behaviors and, in particular, those climates that promote prosocial behavior—commonly defined as “ethical climate(s) of friendship” (Pagliaro et al. 2018; Teresi et al. 2019)—have been shown to be more strongly associated with work performance, organizational identification, and commitment (Treviño et al. 1998; DeConinck 2011; Briggs et al. 2012) than those that suggest a more individualistic behavior—“ethical climate(s) of self-interest.” However, while previous research has demonstrated the positive associations between prosocial ethical climates and organizational outcomes, the direct effects of these climates on individual general well-being are, to date, mostly unexplored. Based on recent studies, we hypothesized that differences in ethical climate are associated with workers’ overall mental well-being.

H4.

The effects on workers’ mental well-being according to WHO-5 vary across the different ethical work climates.

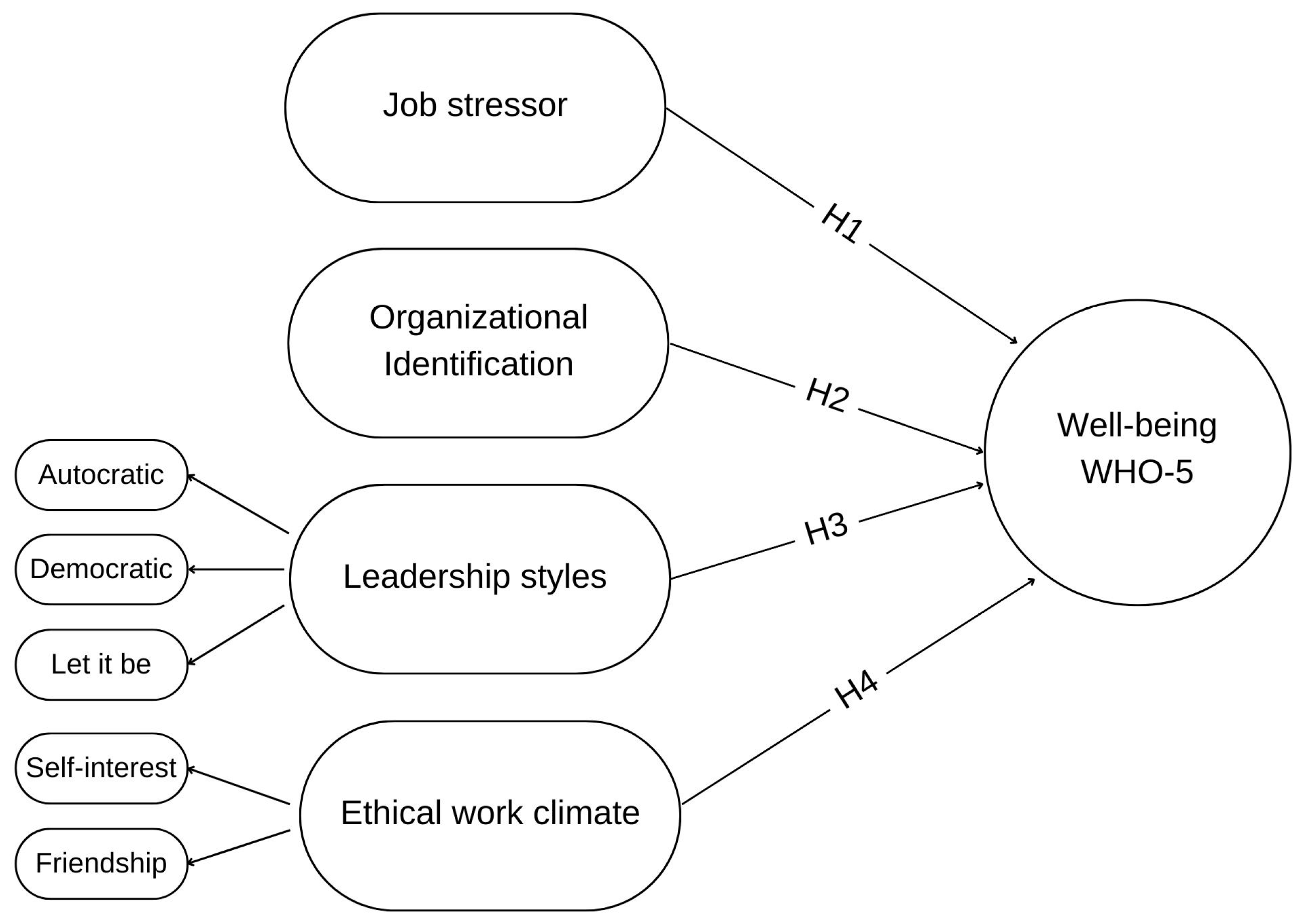

The following research model summarizes the hypotheses formulated in this study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Research model.

The hypotheses of this work are based on the assumption that the time spent at work occupies most of the day. It is plausible that work dynamics are associated with workers’ overall mental well-being. This is reflected in daily activities, family, and social life. Nonetheless, such workers’ mental well-being could play a crucial role in job performance. This involves the necessity of a high concentration of management on these aspects to improve the well-being of workers’ lives and their performance in the company.

3. Research Method

3.1. Design, Participants, and Procedures

The analyses were based on data collection through questionnaires administered in the year 2022. Following a dedicated link, participants were redirected to a questionnaire hosted through Qualtrics software. Participants were informed of the ethical approval and data storage and processing procedures, all in compliance with Regulation (EU) 2016/679 GDPR. Following the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki, participants were informed of their right to refuse to participate in the study or to withdraw consent to participate at any time without reprisal.

The study involved two medium–large-sized Italian companies also with offices abroad. The research reached a total of 390 participants, distributed as shown in Table 1. As can be seen from the table, male respondents represented 64.1% of the sample (compared to 35.9% of women), and the majority of respondents belonged to Generation X and Millennials, which comprised 75% of the total sample. Regarding the tenure in the company, most were respondents with over 10 years of experience (41.9%), 33.3% of respondents had between one and five years, and 14.4% of respondents had between six and ten years. Only 10.4% of the respondents have a tenure of less than one year.

Table 1.

Descriptive analysis of the sample: gender, age, tenure.

3.2. Measures

Well-being index was measured using the World Health Organization—Five Well-Being Index (WHO-5), which is a short self-reported measure of current mental well-being (WHO 1998; Topp et al. 2015). Participants were asked to answer on a six-point Likert scale from 1 (at no time) to 6 (all the time). The value of Cronbach’s Alpha for our survey was α = 0.834. Perceived job stressors were measured using a 6-point Likert scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 6 (completely agree) of 15 questions. For example, workers were asked to rate the following items: “My job is physically tiring”,; “I am constantly under pressure from a heavy workload”,; “My job promotion prospects are poor”.

Organizational identification was assessed through the Italian adaptation of the original six-item scale by Mael and Ashforth (1992) revised for organizational contexts (e.g., “When someone criticizes my organization, I take it as a personal insult”, “The successes of my company are my successes”, “If my company was spoken about badly in the news, I would feel embarrassed”); from 1, “strongly disagree”, to 6, “strongly agree”).

Autocratic leadership was assessed through the six-item scale on a six-point Likert scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 6 (completely agree). They were asked the following questions: “In my experience with this company, employees are supervised closely as to make sure that they do their job”; “In my experience with this company, it is fair to say that most employees are considered to be lazy”; “In my experience with this company, as a rule, supervisors are given rewards or punishments in order to be motivated and achieve organizational objectives”; “In my experience with this company, supervisors think that most employees feel insecure about their work and need direction”; “In my experience with this company, supervisors are the chief judges of the achievements of the members of the group”; “In my experience with this company, supervisors giver orders and clarify procedures”.

Democratic (participative) leadership was assessed through the six-item scale on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 6 (completely agree). Workers were asked to rate the following items: “In my experience with this company, employees are part of the decision-making process”; “In my experience with this company, generally supervisors provide guidance without pressure”; “In my experience with this company, the communication between employees and supervisors is frequent and supportive”; “In my experience with this company, as a rule, supervisors help employees accept responsibility for completing their work”; “In my experience with this company, it is the supervisors’ job to help employees find their passion”; “In my experience with this company, people are considered to be competent and able to do a good job when given a task”.

‘Let it be’ leadership was assessed through the six-item scale on a six-point Likert scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 6 (completely agree). Workers were asked to rate the following items: “In my experience with this company, in complex situations, supervisors let employees work problems out on their own”; “In my experience with this company, leaders stay out of the way of employees as they do their work”; “In my experience with this company, as a rule, leaders allow employees to appraise their own work”; “In my experience with this company, supervisors give employees complete freedom to solve problems on their own”; “In my experience with this company, generally speaking, employees are given little input from their supervisors”; “In my experience with this company, people are left to do their job autonomously”.

The ethical climate of friendship and self-interest were assessed through the six-item scale on a six-point Likert scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 6 (completely agree) (Cullen et al. 1993; Lo Presti et al. 2017). Workers were asked to rate the following items to assess the ethical climate of friendship: “In my company, people care about each other for the good of all concerned”; “In my company, above all, people are concerned with what is best for their colleagues”; “ My company cares about the well-being of each individual”; “In my company, people have the interests of other colleagues at heart”; “In my company, people are primarily concerned with what is best for other colleagues”; “In my company, before making a decision, one expects the interests of the people involved to be taken into account”. The items used to assess the ethical climate of self-interest were as follows: “In my company, people mostly tend to look out for their own interests”; “In my company, there is no place for personal moral and ethical principles”; “In my company, people protect their own interests first”; “In my company, people are primarily concerned with what is best for themselves”.

3.3. Model

The general model (1) used to provide evidence of the model for estimating general workers’ Well-Being Index (WHO-5) is as follows:

where jobstr indicates the level of job stress of the respondents; oi is the level of the organizational identification; lea_aut indicates authoritative leadership style; lea_dem indicates democratic leadership style; lea_let indicates the ‘let it be’ leadership style; eth_friend takes into account the ethical friendship climate; eth_self considers the self-interest ethical climate; and ε is the residual. The model used is an ordinary least-squares (Ols) method, which is a linear regression useful to estimate the unknown parameters in a model.

4. Results

Table 2 shows the correlations between the variables considered in the model and the descriptive statistics. It can be seen that the independent variables were not highly correlated with each other and, therefore, each independent variable contributed unique and non-redundant information to the analysis. There was, therefore, no multicollinearity problem, and the coefficients could be interpreted more reliably due to the absence of highly correlated variables. The values of Cronbach’s alpha coefficients showed a high level of trustworthiness.

Table 2.

Correlation between the main covariates, descriptive statistics, and Cronbach’s Alphas.

Table 3 reports the empirical evidence of the survey. Column (1) shows the econometric results for job stressors and organizational identification. Columns (2) and (3) report the results considering the leadership styles and the firm’s ethical climate in different steps. Models (2) and (3) report a reduced number compared to the total number of participants in model (1) due to the lack of answers to some survey questions by the participants.

Table 3.

Workers’ well-being (WHO-5) as the dependent variable. Ols, estimations econometric model.

The econometric results clearly show a strong negative connection between job stressors and workers’ well-being, corresponding to the many studies that have suggested how job stress may be associated with negative health and mental well-being outcomes. This trend occurred across all model specifications. Job stressors can have a negative influence on worker satisfaction and contribute to mental health problems beyond the workplace (H1). Hence, job stress can affect personal lives and social relations, with repercussions on the general well-being of the worker and on his work productivity.

The results show a positive relationship between organizational identification and workers’ mental well-being (H2). This trend occurred clearly across all model specifications. Overall, we can state that organizational identification and well-being are closely connected, and the strengthening of one can lead to improvements in the other. Indeed, organizational identification refers to the degree to which employees feel a sense of belonging and attachment to their organization. Workers who recognize higher levels of organizational identification show higher levels of well-being. This is important not only for personal life but also for better performance in the workplace.

The consideration of the various leadership styles reveals some interesting reflections. By distinguishing leadership style, models (2) and (3) show that only democratic leadership was positively associated with higher workers’ well-being (H3). Leaders that invite their subordinates to participate in the decision-making process, as well as to share opinions and ideas, can drive more effective collaboration and trust among team members. Authoritative and ’let it be’ leadership styles appeared to have no statistically significant impact on workers’ well-being.

Furthermore, the perception of the ethical climate seems to be another driver in the consideration of workers’ well-being. Indeed, the ethical climate is a crucial component of a healthy work environment and can have a large impact on employee satisfaction, productivity, and the overall success of the organization. The results of model (3) indicate that when employees perceived an ethical climate of friendship, this was associated with greater workers’ mental well-being (H4). The ethical climate of self-interest, on the other hand, did not seem to contribute to improving the well-being of workers.

5. Discussion

Recent studies have highlighted that job stressors, organizational identification, leadership style, and ethical climate seem to be the most important drivers of job performance and well-being in the workplace. Our results confirm the idea that these variables have an effective role and can also explain workers’ mental well-being (so-called WHO-5 Well-Being Index) beyond the workplace. The focus of this research was to investigate the linkages between working aspects (job stressors, organization identification, leadership styles, and ethical work climate) and workers’ overall mental well-being in the post-COVID-19 period. Indeed, the pandemic period of COVID-19 could have caused stressful effects on the mental well-being of workers regardless of company drivers (Foti et al. 2023).

The main results show that job stressors had a significant and negative relation with workers’ mental well-being (Hypothesis 1). This confirms the association between work dynamics and private life, reinforcing earlier findings by Karasek (1979), Tyssen et al. (2000), and Mensah (2021). These authors found that stress at work has an important role in several fields of private and social life. The opportunity of reducing the job stressor can operate as a driving force to improve the standard of living of the workers, identifying bridges between better workers’ well-being and the improvement of labor productivity.

Concerning the effect of organizational identification, we found that individuals with higher levels of organizational identification held more positive mental well-being (H2). Such findings appear to confirm results from previous literature about job satisfaction effects inside the workplace (Wegge et al. 2006; Lee et al. 2015; Greco et al. 2022). Increasing the sense of organizational identification with the company can be a challenging task for management.

Recently, several studies have investigated the utility of splitting leadership styles to grasp the possible impacts on worker satisfaction, calling for new insights to measure this topic (Huang et al. 2010; Ahmed Iqbal et al. 2021). Indeed, the connection between leadership styles such as autocratic, participative, and laissez-faire leadership and employees’ overall well-being remains an under-researched topic, as leadership styles have been explored mostly in terms of their impact on job performance. Hence, our results show that participative leadership is also positively associated with the workers’ overall mental well-being (H3). Such results suggest additional insights with respect to the previous literature, which has been focused only on the workplace (Kim 2002; Chan 2019). Furthermore, workers’ behavior has been recently associated with ethical work climate, highlighting the positive association between ethical climate and organizational outcomes (Treviño et al. 1998; DeConinck 2011; Pagliaro et al. 2018), as well as work performance and commitment. Our results extend this framework by demonstrating that the ethical climate of friendship also has positive effects on mental well-being outside the workspace (H4).

The findings of this article represent a valuable contribution toward a deeper understanding of workers’ well-being, with implications from research, management, and policymaking standpoints as follows.

5.1. Implications for Research

The insights gained from this research on a sample of workers in Italian firms contribute to the current debate on the best managerial organizational practices, highlighting how (and which) factors can significantly affect workers’ well-being.

Furthermore, the findings of relationships between leadership styles, ethical behavior, organizational identification, and workers’ well-being beyond the workplace are interesting. Since these effects have not been consistently found in the literature, future studies in this direction may be needed to investigate these relationships further.

Indeed, alongside the established factors extensively examined in current literature, such as workers’ well-being inside the workplace, our study uncovered significant correlations between managerial drivers and workers’ overall well-being. Nonetheless, further examinations may be necessary to investigate this phenomenon for a larger number of workers and in other countries to test any differences due to the specific national culture.

5.2. Practical Implications

The results of the study confirm the growing importance held by workers’ mental well-being in the governance of the companies and the growing role of managers in leading the best practices to improve workers’ well-being according to business success. Managers can take practical actions to improve company management regarding job stress, organizational identification, leadership style, and corporate ethical climate.

The opportunity of reducing job stressors can operate as a driving force to improve the standard of living of workers. Management should examine whether their collaborators constantly feel under pressure due to a heavy workload, which forces workers to work very quickly without leaving room for reflection. Management should also investigate other important causes that could increase stress at work, such as the ability of employees to develop new skills and the feeling of recognition for the work done.

Another result of this work suggests that individuals with higher levels of organizational identification have more positive mental well-being. This result can be achieved by representing the company in an ethical and transparent way to the outside world through the correct manager’s behavior. A company is a community of people with common interests, and shared values united to achieve a common goal. Workers want to identify with an organization that is not just focused on profits: people want to work for an organization whose values they share, and they want to be proud of what they produce and admire the colleagues they work with (DeConinck 2011). This has a positive effect on workers’ general mental well-being.

Following that participative leadership is positively associated with workers’ overall mental well-being, managers could improve workers’ overall well-being by following several drivers. For example, managers could involve workers in the decision-making process, communicate frequently and in a supportive manner, and encourage workers to take responsibility when it comes to performing their work. These suggestions could increase the involvement of workers in company objectives and the perception of being an important piece in company dynamics and not just an executive tool. These aspects have an impact on general mental well-being and, therefore, on the social aspects of private life, with undoubted positive effects on productivity in carrying out the work (Sutarto et al. 2021).

Moreover, managers could create clear ethical standards that lead the workers’ behavior through a specific code of conduct or by encouraging open communication and a culture of transparency. However, recent literature has shown that a good example of manager behavior (honesty, integrity) can be much more effective for creating a suitable ethical climate in a company than formal procedures (the so-called ‘Tone at the Top’). Tone at the Top underlines how “the example must come from the top management”, who must promote the growth of an ethical climate by acting on the drivers of culture and solid corporate values. The Tone at the Top describes the ethical atmosphere in the workplace created by the behavior of the top of the organization. Whatever the level of “tone” is, it will play a significant role in the behavior of the company’s workers (Patelli and Pedrini 2015; Onesti and Palumbo 2023).

6. Conclusions

This study focused on the analysis of the relationship between organizational identification, leadership styles, ethical behavior, and workers’ mental well-being. We aimed to fill the following gaps in the literature: one concerning the limited presence of studies about this topic in the post-pandemic COVID-19 period and the other regarding the considerations of the main factors linked to the workers’ well-being together in the same model. Finally, we tested the influence of job stressors, organizational identification, leadership style, and ethical climate on workers’ general mental well-being (so-called WHO-5 Well-Being Index) beyond the workplace. The paper is based on data obtained through questionnaires administered in the year 2022 hosted through Qualtrics software. The study involves two medium–large-sized Italian companies also with offices abroad, reaching a total of 390 participants.

The results show a negative relationship between job stressors and mental workers’ well-being. Moreover, our study identified that the level of organizational identification, participative leadership, and the ethical climate of friendship has a positive relation with workers’ mental well-being. Our findings represent a valuable contribution toward a deeper understanding of this topic, with implications from both research and management. Indeed, the insights gained from this research contribute to the current consideration of workers’ well-being, highlighting that well-being outside the workplace can significantly affect the general consideration of workers both in private and social life, as well as productivity at work. The results of the study confirm the importance of management actions in fixing the general mental well-being of workers. Indeed, our study highlights how management can engage specific actions to favor the main drivers related to the improvement of well-being, such as better organizational identification and a participative leadership style, a good example—Tone at the Top—to create a suitable and ethical climate. The company’s ability to strategically retain capable collaborators is becoming increasingly fundamental, especially in light of the recent increase in resignations. Being able to ensure high workers’ well-being through suitable managerial policies can greatly benefit the success and performance of the company.

The present study has certain limitations that need to be considered for future research. First, the empirical models have a cross-sectional design. This setting does not allow us to definitively define the causal inferences about the relationship between the considered variables. Future research could overcome this limit by proposing longitudinal data for the study of the same variables. Moreover, we cannot exclude a potential limitation of the use of self-report measures, although we checked the internal consistency of the answers and eliminated possible outliers. We eliminated potential bias through the anonymity of the response. Further studies could adopt the implicit methods to reveal an individual’s hidden or subconscious biases as a so-called implicit association test to avoid potential bias in the answer of the participants. In addition, future research might consider a higher number of participants for a higher number of firms. Despite these limitations, the results of this study show that the relationship between the main drivers of company management and workers’ mental well-being is worth investigating. This appears to support the strategic choices of management in the workers’ well-being policies.

Funding

This research was funded by European Social Fund—PON, grant number 53-I-14750-1.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to Regulation (EU) 2016/679 GDPR.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahmed Iqbal, Zulfiqar, Ghulam Abid, Muhammad Arshad, Fouzia Ashfaq, Muhammad Ahsan Athar, and Qandeel Hassan. 2021. Impact of Authoritative and Laissez-Faire Leadership on Thriving at Work: The Moderating Role of Conscientiousness. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 11: 667–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, Cláudia, and Paula C. Neves. 2022. Perceived Organizational Support, Coworkers’ Conflict and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Mediation Role of Work-Family Conflict. Administrative Sciences 12: 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, Blake E., and Fred Mael. 1989. Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review 14: 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, Bruce J., Fred O. Walumbwa, and Todd J. Weber. 2009. Leadership: Current theories, research, and future directions. Annual Review of Psychology 60: 421–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, Bernard M. 1985. Leadership and Performance beyond Expectations. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, Bernard M., and Ronald E. Riggio. 2006. Transformational Leadership. New York: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, Nadeem, Ghulam M. Maitlo, Naveed Shaikh, Muhammad A. Hashmi, and Faiz M. Shaikh. 2012. The impact of autocratic and democratic leadership style on job satisfaction. International Business Research 5: 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchflower, David G., and Andrew J. Oswald. 2011. International happiness: A new view on the measure of performance. Academy of Management Perspectives 25: 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Susanne, Claudia Peus, Silke Weisweiler, and Dieter Frey. 2013. Transformational leadership, job satisfaction, and team performance: A multilevel mediation model of trust. The Leadership Quarterly 24: 270–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, Elten, Fernando Jaramillo, and William A. Weeks. 2012. The influences of ethical climate and organization identity comparisons on salespeople and their job performance. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management 32: 421–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Andrew, Andy Charlwood, and David A. Spencer. 2012. Not all that it might seem: Why job satisfaction is worth studying despite it being a poor summary measure of job quality. Work, Employment and Society 26: 1007–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Michael E., Linda K. Treviño, and David A. Harrison. 2005. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 97: 117–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, Alan. 2013. Leadership and Organizations. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bryson, Alex, and George MacKerron. 2017. Are You Happy While You Work? The Economic Journal 127: 106–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budd, John W., and David A. Spencer. 2015. Worker well-being and the importance of work: Bridging the gap. European Journal of Industrial Relations 21: 181–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Simon C. H. 2019. Participative leadership and job satisfaction: The mediating role of work engagement and the moderating role of fun experienced at work. Leadership & Organization Development Journal 40: 319–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, Samantha, Christine A. Henle, Lynn Shore, and Samantha Stelman. 2017. Where there is light, there is dark: A review of the detrimental outcomes of high organizational identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior 38: 184–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosma, Alina, András Költő, Yekaterina Chzhen, Dorota Kleszczewska, Michal Kalman, and Gina Martin. 2022. Measurement Invariance of the WHO-5 Well-Being Index: Evidence from 15 European Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 9798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, John B., Bart Victor, and James W. Bronson. 1993. The ethical climate questionnaire: An assessment of its development and validity. Psychological Reports 73: 667–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giorgio, Andrea, Massimiliano Barattucci, Manuel Teresi, Giovanni Raulli, Chiara Ballone, Tiziana Ramaci, and Stefano Pagliaro. 2023. Organizational identification as a trigger for personal well-being: Associations with happiness and stress through job outcomes. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 33: 138–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeConinck, James B. 2011. The effects of ethical climate on organizational identification, supervisory trust, and turnover among salespeople. Journal of Business Research 64: 617–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Wen, and Phyllis Moen. 2022. Working More, Less or the Same During COVID-19? A Mixed Method, Intersectional Analysis of Remote Workers. Work and Occupations 49: 143–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felstead, Alan, Duncan Gallie, Francis Green, and Golo Henseke. 2019. Conceiving, designing and trailing a short-form measure of job quality: A proof-of-concept study. Industrial Relations Journal 50: 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foti, Giulia, Giorgia Bondanini, Georgia Libera Finstad, Federico Alessio, and Gabriele Giorgi. 2023. The Relationship between Occupational Stress, Mental Health and COVID-19-Related Stress: Mediation Analysis Results. Administrative Sciences 13: 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garraio, Carolina, Maria I. Barradas, and Marisa Matias. 2023. Organisational and Supervisor Support Links to Psychological Detachment from Work: Mediating Effect of Work-family Conflict on Dual-earner Couples. Applied Research Quality Life 18: 957–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastil, John. 1994. A definition and illustration of democratic leadership. Human Relations 47: 953–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, Carol, Kate Laffan, and Sergio Pinto. 2018. Well-being in metrics and policy. Science 362: 287–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greco, Lindsey M., Jeanine P. Porck, Sheryl L. Walter, Alex J. Scrimpshire, and Anna M. Zabinski. 2022. A meta-analytic review of identification at work: Relative contribution of team, organizational, and professional identification. Journal of Applied Psychology 107: 795830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, Imran, Muhammad U. Ijaz, and Meghna Sabharwal. 2022. The impact of human resources environment and organizational identification on employees’ psychological well-being. Public Personnel Management 51: 71–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Gregory E., and James E. Cameron. 2005. Multiple Dimensions of Organizational Identification and Commitment as Predictors of Turnover Intentions and Psychological Well-Being. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue Canadienne des Sciences du Comportement 37: 159–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, Alexander S. 2004. Psychology in Organizations. New York: Sage Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobman, Elisabeth V., Chris J. Jackson, Nerina L. Jimmieson, and Robin Martin. 2011. The effects of transformational leadership behaviours on follower outcomes: An identity-based analysis. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 20: 553–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, Davis R., and Arne L. Kalleberg. 2019. Declining job quality in the United States: Explanations and evidence. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 5: 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Xu, Joyce Iun, Aili Liu, and Yaping Gong. 2010. Does participative leadership enhance work performance by inducing empowerment or trust? The differential effects on managerial and non-managerial subordinates. Journal of Organizational Behavior 31: 122–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inceoglu, Ilke, Geoff Thomas, Chris Chu, David Plans, and Alexandra Gerbasi. 2018. Leadership behavior and employee well-being: An integrated review and a future research agenda. The Leadership Quarterly 29: 179–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Anya, Shanta Dey, Helena Nguyen, Markus Groth, Sadhbh Joyce, Leona Tan, Nicholas Glozier, and Samuel B. Harvey. 2020. A review and agenda for examining how technology-driven changes at work will impact workplace mental health and employee well-being. Australian Journal of Management 45: 402–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, Timothy A., and Ronald F. Piccolo. 2004. Transformational and transactional leadership: A meta-analytic test of their relative validity. Journal of Applied Psychology 89: 755–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, Timothy A., Joyce E. Bono, Remus Ilies, and Megan W. Gerhardt. 2002. Personality and leadership: A qualitative and quantitative review. Journal of Applied Psychology 87: 765–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karasek, Robert A., Jr. 1979. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quartely 24: 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Soonhee. 2002. Participative management and job satisfaction: Lessons for management leadership. Public Administration Review 62: 231–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, Craig, and S. Alexander Haslam. 2010. Your Place or Mine? Organizational Identification and Comfort as Mediators of Relationships Between the Managerial Control of Workspace and Employees’ Satisfaction and Well-being. British Journal of Management 21: 717–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, Angela, Chris Warhurst, Dennis Nickson, and Eli Dutton. 2015. More than a feeling: Using hotel room attendants to improve understanding of job quality. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 26: 1547–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuoppala, Jaana, Anne Lamminpää, Juha Liira, and Harri Vainio. 2008. Leadership, job well-being, and health effects—A systematic review and a meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 50: 904–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, P. C. F., L. S. Too, Peter Butterworth, K. Witt, N. Reavley, and A. J. Milner. 2020. A systematic review on the effect of work-related stressors on mental health of young workers. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 93: 611–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Eun-Suk, Tae-Youn Park, and Bonjin Koo. 2015. Identifying organizational identification as a basis for attitudes and behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin 141: 1049–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, Kurt, Ronald Lippitt, and Raplh K. White. 1939. Patterns of aggressive behavior in experimentally created “social climates”. The Journal of Social Psychology 10: 269–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Presti, Alessandro, Stefano Pagliaro, Massimiliano Barattucci, and Davide Marcato. 2017. Examining the behavioral effects of ethical climate. The role of organizational identification and moral disengagement. Paper presented at the 18th Conference of the European Association of Work and Organizational Psychology, Dublin, Ireland, May 19. [Google Scholar]

- Mael, Fred, and Blake E. Ashforth. 1992. Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior 13: 103–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, Aziz. 2021. Job Stress and Mental Well-Being among Working Men and Women in Europe: The Mediating Role of Social Support. International Journal of Environment Research and Public Health 18: 2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, Ana, Tiago Encarnação, João Viseu, and Manuel Au-Yong-Oliveira. 2023. Conflict (Work-Family and Family-Work) and Task Performance: The Role of Well-Being in This Relationship. Administrative Sciences 13: 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazareno, Luísa, and Daniel S. Schiff. 2021. The impact of automation and artificial intelligence on worker well-being. Technology in Society 67: 101679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolova, Milena, and Femke Cnossen. 2020. What makes work meaningful and why economists should care about it. Labour Economics 65: 101847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyberg, Anna. 2009. The Impact of Managerial Leadership on Stress and Health among Employees. Solna: Karolinska Institutet (Sweden). [Google Scholar]

- Onesti, Gianni, and Riccardo Palumbo. 2023. Tone at the Top for Sustainable Corporate Governance to Prevent Fraud. Sustainability 15: 2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliaro, Stefano, Alessandro Lo Presti, Massimiliano Barattucci, Valeria A. Giannella, and Manuela Barreto. 2018. On the effects of ethical climate (s) on employees’ behavior: A social identity approach. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patelli, Lorenzo, and Matteo Pedrini. 2015. Is Tone at the Top Associated with Financial Reporting Aggressiveness? Journal of Business Ethics 126: 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, Michael G. 1998. To Be or not To Be. Central questions in organizational identification. Identity in Organizations 24: 171–207. [Google Scholar]

- Riketta, Michael. 2005. Organizational identification: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior 66: 358–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnicka, Anna, Joseph W. Newbold, Dave Cook, Marta E. Cecchinato, Sandy Gould, and Anna L. Cox. 2020. Eworklife: Developing Effective Strategies for Remote Working during the COVID-19 Pandemic. In Eworklife: Developing Effective Strategies for Remote Working during the COVID-19 Pandemic. The New Future of Work Online Symposium. Available online: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10106475/1/Eworklife%20developing%20effective%20strategies%20for%20remote%20working%20during%20the%20COVID-19%20pandemic.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- Schaufeli, Wilmar B., and Arnold B. Bakker. 2004. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior 25: 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidlinger, Saul. 1994. The Lewin, Lippitt and White study of leadership and “social climates” revisited. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy 44: 123–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serenko, Aleaxander. 2023. The Great Resignation: The great knowledge exodus or the onset of the Great Knowledge Revolution? Journal of Knowledge Management 27: 1042–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillince, John A. A., and Ben D. Golant. 2018. Making connections: A process model of organizational identification. Human Relations 71: 349–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skogstad, Anders, Ståle Einarsen, Torbjørn Torsheim, Merethe S. Aasland, and Hilde Hetland. 2007. The destructiveness of laissez-faire leadership behaviour. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 12: 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffens, Niklas K., Alexander S. Haslam, Sebastian C. Schuh, Jolanda Jetten, and Rolf van Dick. 2017. A meta-analytic review of social identification and health in organizational contexts. Personality and Social Psychology Review 21: 303–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, Arthur A., and Christopher Mackie. 2014. Subjective Well-Being: Measuring Happiness, Suffering, and Other Dimensions of Experience. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Wei, and Juhee Hahn. 2022. A multi-level study on whether ethical climate influences the affective well-being of millennial employees. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 1028082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutarto, Auditya P., Shanti Wardaningsih, and Wika H. Putri. 2021. Work from home: Indonesian employees’ mental well-being and productivity during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Workplace Health Management 14: 386–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teresi, Manuel, Davide D. Pietroni, Massimiliano Barattucci, Valeria A. Giannella, and Stefano Pagliaro. 2019. Ethical climate (s), organizational identification, and employees’ behavior. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessema, Mussie M., Goitom Tesfom, Marcy A. Faircloth, Mussie Tesfagiorgis, and Paulos Teckle. 2022. The “Great Resignation”: Causes, Consequences, and Creative HR Management Strategies. Journal of Human Resource and SustainabOility Studies 10: 161–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topp, Christian W., Søren D. Østergaard, Susan Søndergaard, and Per Bech. 2015. The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 84: 167–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortia, Ermanno C. 2008. Worker well-being and perceived fairness: Survey-based findings from Italy. The Journal of Socio-Economics 37: 2080–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, Linda K., Kenneth D. Butterfield, and Donald L. McCabe. 1998. The ethical context in organizations: Influences on employee attitudes and behaviors. Business Ethics Quarterly 8: 447–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyssen, Reidar, Per Vaglum, Nina T. Grønvold, and Øivind Ekeberg. 2000. The impact of job stress and working conditions on mental health problems among junior house officers. A nationwide Norwegian prospective cohort study. Medical Education 34: 374–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victor, Bart, and John B. Cullen. 1988. The organizational bases of ethical work climates. Administrative Science Quarterly 33: 101–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegge, Jürgen, Rolf Van Dick, Gary K. Fisher, Christiane Wecking, and Kai Moltzen. 2006. Work motivation, organisational identification, and well-being in call centre work. Work & Stress 20: 60–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. 1998. Wellbeing Measures in Primary Health Care/The Depcare Project. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Wiesenfeld, Batia M., Sumita Raghuram, and Raghu Garud. 2001. Organizational identification among virtual workers: The role of need for affiliation and perceived work-based social support. Journal of Management 27: 213–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadeun-Antuñano, Monica. 2019. Indigenous perspectives of wellbeing: Living a good life. In Good Health and Well-Being. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 436–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Zhe, Juan Wang, and Ming Jia. 2022. Multilevel Examination of How and When Socially Responsible Human Resource Management Improves the Well-Being of Employees. Journal of Business Ethics 176: 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).