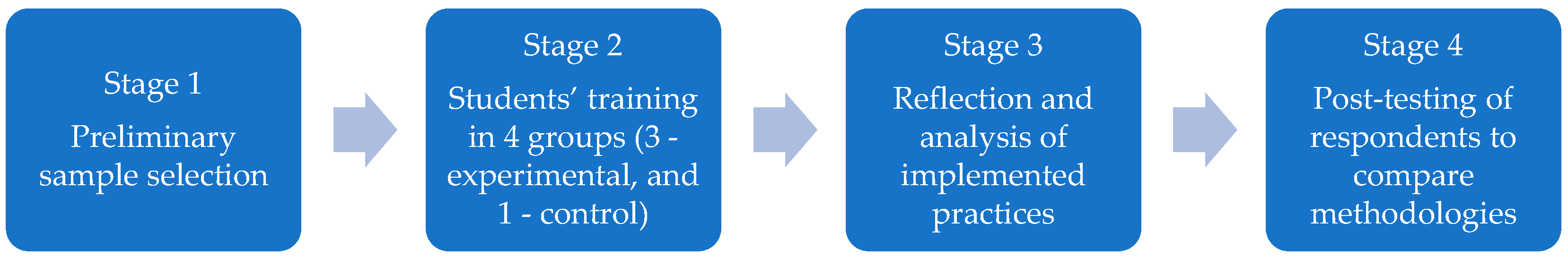

3.1. First Phase

According to the first survey, the majority of students answered that entrepreneurship did not require special education. This was stated by more than 50% of respondents. Another 22% said that they had doubts, but 26% stated that they were confident that special education was essential. Yet, when asked about the need for special training and courses, 56% gave a positive answer, and 20% said they were sure that it was not necessary. A total of 24% of respondents indicated uncertainty in their responses. The statement that the university was capable of imparting adequate knowledge and skills was disagreed with by 57 percent of students. A total of 64% of students expressed support for this statement, while 8% disagreed and 28% indicated uncertainty. Among the student respondents, 51% disagreed with the notion that entrepreneurship necessitates a distinct societal position, whereas 38% expressed the belief that such a distinct position is indeed required. Additionally, 13% of the students did not provide a definitive response to this question.

The survey suggests that 62% of students were not ready to start businesses after graduation, while 19% answered that it was possible, with another 19% being undecided. In addition, a majority of students (56%) expressed the need for practical, hands-on experience to establish businesses. Conversely, 19% of students stated that such experience was not required, while 25% remained undecided on the matter. According to the findings, a significant proportion of students (30%) expressed confidence in possessing adequate skills to initiate entrepreneurial ventures. Conversely, a majority (47%) acknowledged their insufficient skill set for commencing businesses, while 23% of the students remained uncertain in their assessment. Upon evaluation, it was revealed that 53% of students expressed their lack of willingness to embark on entrepreneurial endeavors upon graduation. In contrast, 34% of students indicated their readiness to commence business ventures, while 13% remained undecided on the matter. Opinions on entrepreneurial skills were divided almost equally: 39% answered that they could start businesses, with 41% considering themselves not ready and 20% remaining undecided (See

Table 1).

The presented data suggest that most students do not believe it necessary to receive special education, but see the need to have the skills necessary to run their businesses. Students believe they can obtain such skills and relevant expertise during employment. Very few students are ready to become entrepreneurs after graduation.

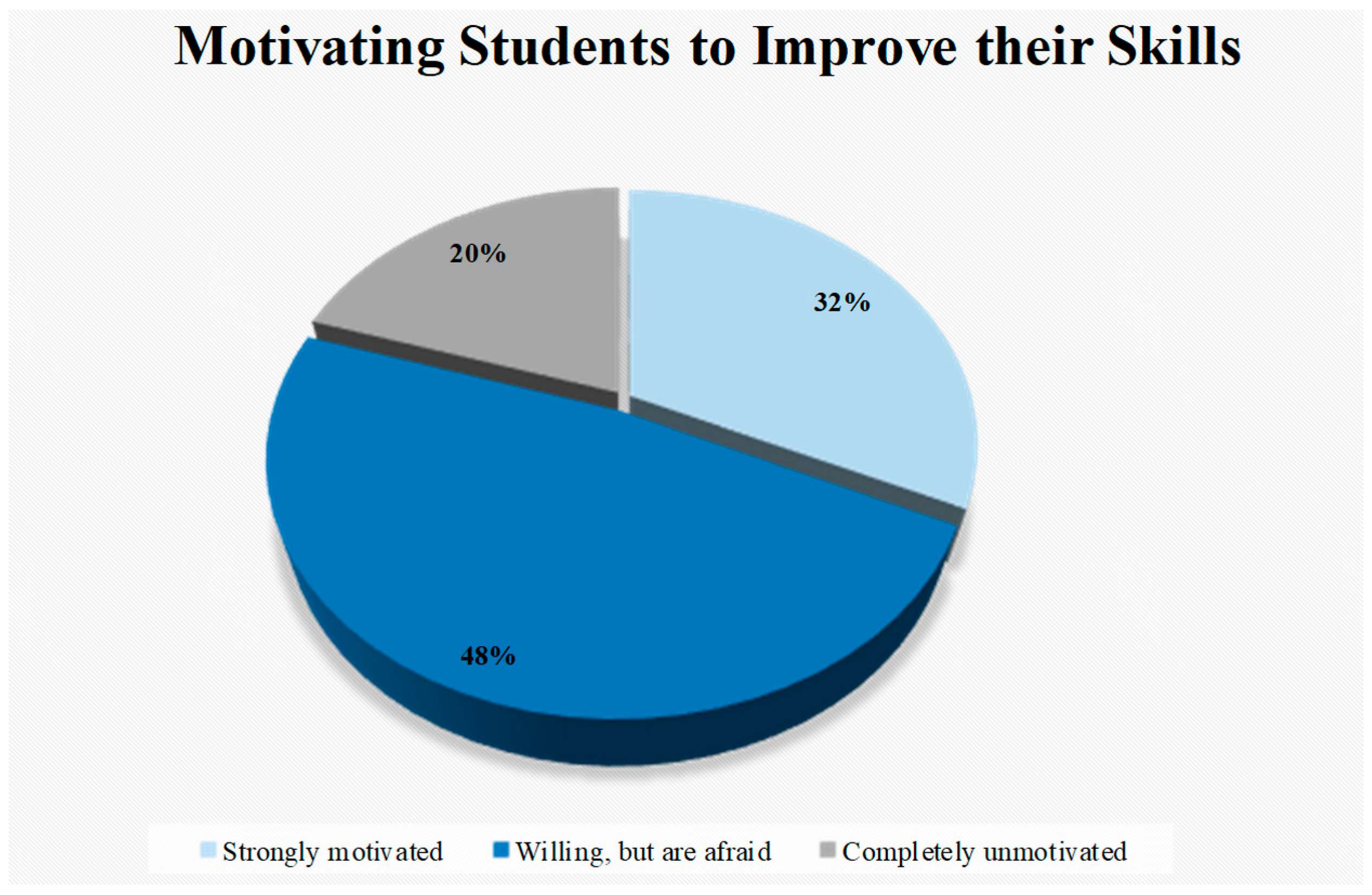

The second survey focused on students’ motivations to improve their entrepreneurial skills. The findings were as follows: 32% of students were strongly motivated to improve their entrepreneurial skills.

3.2. Second Phase

The first phase of the research (which consisted of surveys on the motivation and competence among students before the experiment and the introduction of new practices) revealed that many students had doubts or a lack of motivation to start a business at all. A large portion of students were ready to try entrepreneurship.

After the first phase, the students were divided into four groups, and work on implementing the relevant approaches began.

The first group was trained using the approaches applied in U.S. universities. The second group was trained using the European method—sharing expertise among students and entrepreneurs and communicating with businessmen. The third group relied on the Korean approach to improve students’ motivation and knowledge of entrepreneurship. The fourth (control) group was set up to monitor the effectiveness of alternate methods in comparison with those currently used to improve entrepreneurial competence.

The U.S. methods introduced for the first group involved several of the 11 practices that are widely used in the U.S. and appear to be effective. More specifically:

Combination of the traditional program and additional classes;

Involvement of students in the teaching of undergraduates;

Conducting joint classes and research with students from other universities;

Such U.S. practices should reinforce the mission of universities and the traditional value of education. Several aspects are important to U.S. universities and play a particular role in the design of learning activities:

Careful choice of partners with whom to share expertise, followed by discussion of the community, university, or partner needs;

The partner’s sensitivity and responsiveness to the research and teaching requirements, and their willingness to promote innovation;

Proactive exchange and sharing of discoveries, talented students, research findings, and assistance with uptake by the partner (

Crawley et al. 2020).

Ongoing sharing and exchange of knowledge, discoveries, research findings, and discussions take place both formally and informally, and provide more proactive approaches and opportunities to conducting collaborative projects, sharing maps, and participating together in professional development.

3.4. South Korean Methods for Enhancing Student Competence and Knowledge Transfer

The South Korean method is based on improving students’ motivations to learn and gain additional knowledge (

Hytti et al. 2010). This was the approach chosen for the third group of students. According to the survey, a large proportion of students did not want or were afraid to become entrepreneurs. Aside from fears of not being able to handle their businesses, such situations also result from a lack of motivation. The Korean method focuses on improving motivation.

Professional development depends primarily on the student’s desires and needs. Each student establishes personal goals that encompass both their aspirations and the capabilities to be attained throughout their academic journey. In this way, knowledge sharing and professional development are related to motivation. We broke these down into six main points addressing the reasons for becoming an entrepreneur:

Professional achievements: The goal is to enhance students’ abilities to advance and build their careers and to provide additional professional and entrepreneurial development opportunities;

Social security is about enhancing students’ abilities to contribute to society through entrepreneurial skills;

Social relation provides incentives to learn entrepreneurship and gain new skills while paying special attention to building communication with others;

Expectations encompass fulfilling the requirements and desires of various stakeholders in students’ lives, including their loved ones, parents, teachers, and friends;

Social escape—meeting the goal of escaping an unpleasant and boring life;

Cognitive interest—this involves the students’ desire to improve their knowledge and skills, making it possible to enjoy learning and receive new information (

Good and Brophy 1990).

The study focuses on exploring how students can adjust their learning. According to this study, adaptation and assimilation have a positive effect on entrepreneurial learning, and mediate between the six motivation factors and entrepreneurial intentions. The study suggested that motivation for professional achievements increased by 10%, motivation to acquire new knowledge increased by 15%, and the entrepreneurial intentions of students increased by 12%. The study validated the premise that motivation for entrepreneurial achievements positively affects the development of entrepreneurial competence among students.

When students improve their skills, share knowledge, and improve their competence, they can later propose new ways of working and methods for business development (

Krueger et al. 2000).

The South Korean research focuses on students’ motivations to develop and enhance their entrepreneurial competence. The results show that many students want to improve their entrepreneurial competencies, specifically through knowledge sharing. For example, engineering and economics students can exchange information based on the six motivation factors listed above.

The fourth group was the control group. For students in this group, the same knowledge-sharing and professional development techniques commonly used at Russian universities were applied. The education system in the Russian Federation has only recently begun to focus its attention on the development of entrepreneurial skills among students. The learning model used to focus on state academic standards, which did not address improving entrepreneurial competence, but rather focused on training high-end professionals in specific areas (

GEM 2021).

Increased interest in the development of entrepreneurial competence requires choosing the most appropriate teaching methods to build effective knowledge in entrepreneurship. Innovative and creative methods of transferring knowledge, designed to teach students to analyze problems from different perspectives, should be implemented. The ideal approach seems to focus on developing the key skills that are necessary for strong entrepreneurial competence. The foundation comprises a combination of essential skills, including planning, qualitative analysis, and the capacity to navigate unforeseen and critical situations effectively (

Glukhikh 2016).

Case methods, training programs, master classes, communication between students, and knowledge sharing with businesses are effective methods that are not widely used, but are desirable. They profile themselves to be operational, but, due to some difficulties, they are not applied in the training of students (

Glukhikh 2015).

At this point, the case method and very rare instances of training programs and master classes are used. Such methods can be quite effective if used with the required frequency.

3.5. Third Phase

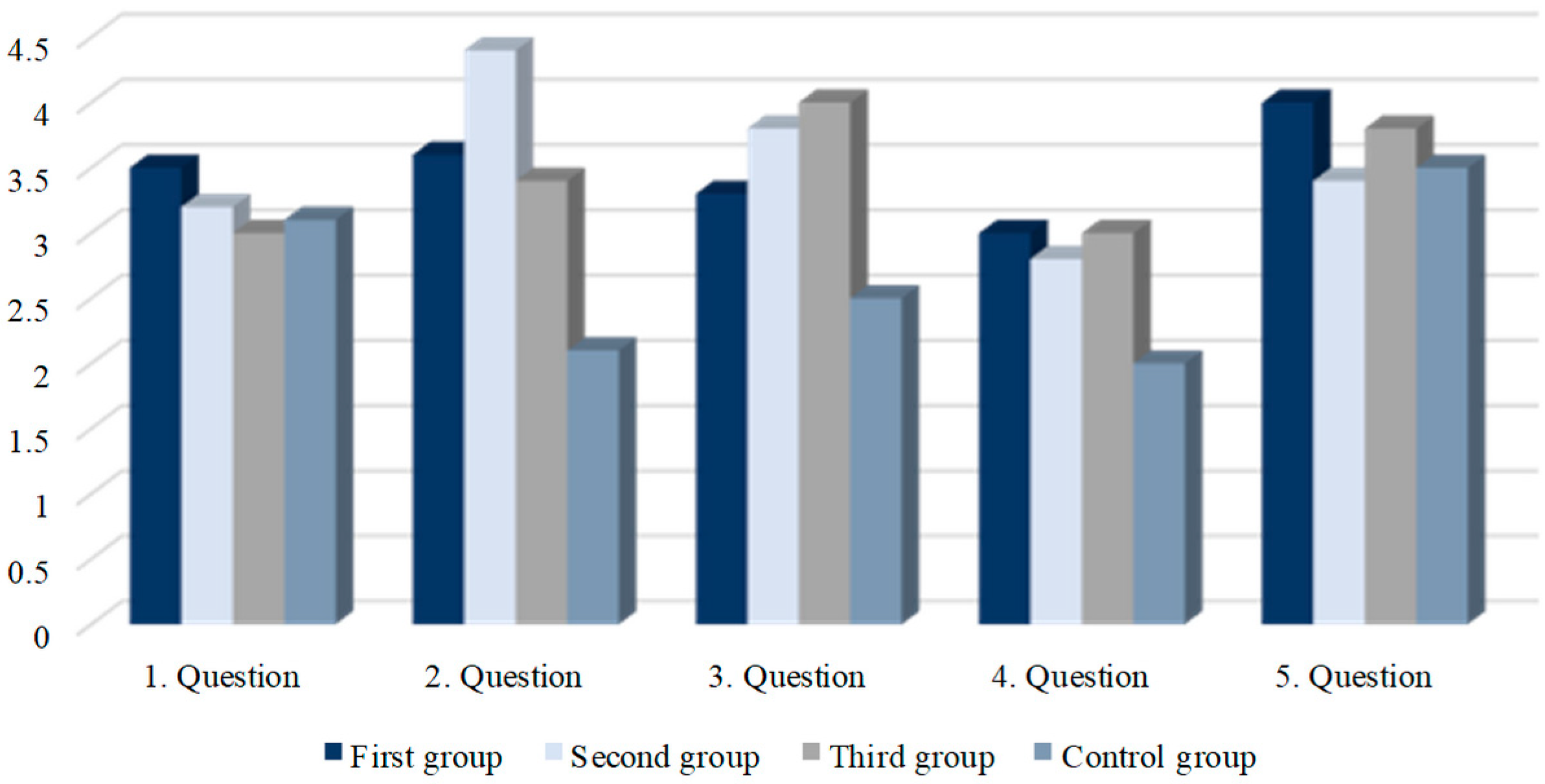

The practices existing in other countries were adopted from November 2020 to June 2021, and afterward, to measure their effectiveness, it was necessary to test how the students’ attitudes to sharing knowledge and improving entrepreneurial competence changed. Two tests were conducted to evaluate the implementation of the new methods. In the first case, students were asked to rate their skill improvements on a five-point scale. The students were required to answer the following questions:

Question: How do you assess your knowledge and abilities at the beginning of your training?

Question: Was the training effective?

Question: How can you assess your competence after the introduction of new methods?

Question: How much has your level improved?

Question: How do you rate your ability to start a business? (See

Figure 3).

These findings suggest that at the beginning of the study, students mostly rated their skills and knowledge at the same level—3.5 out of 5 points. The results from the implementation of the new methods imply that the European methodology was believed to be the most effective, rated 4.4 out of 5 points, while the least effective methods were used in the control group, who were trained without any changes introduced (2.8 out of 5 points). Improved competence was observed in the group that used the European methods (with a score of 3.8 out of 5 points) and South Korean methods (with a score of 4 out of 5 points). Yet, the U.S. innovations were rated slightly lower, with a score of 3.3 out of 5 points, and the absence of innovations in the control group was rated even lower, with 3 out of 5 points. The improvement in entrepreneurial competence was almost identical in the three groups which relied on the new ways of sharing knowledge, but it was significantly lower in the group in which new techniques were not used. Interestingly, at the end of the study, students in all four groups rated their opportunities to start a business almost identically.

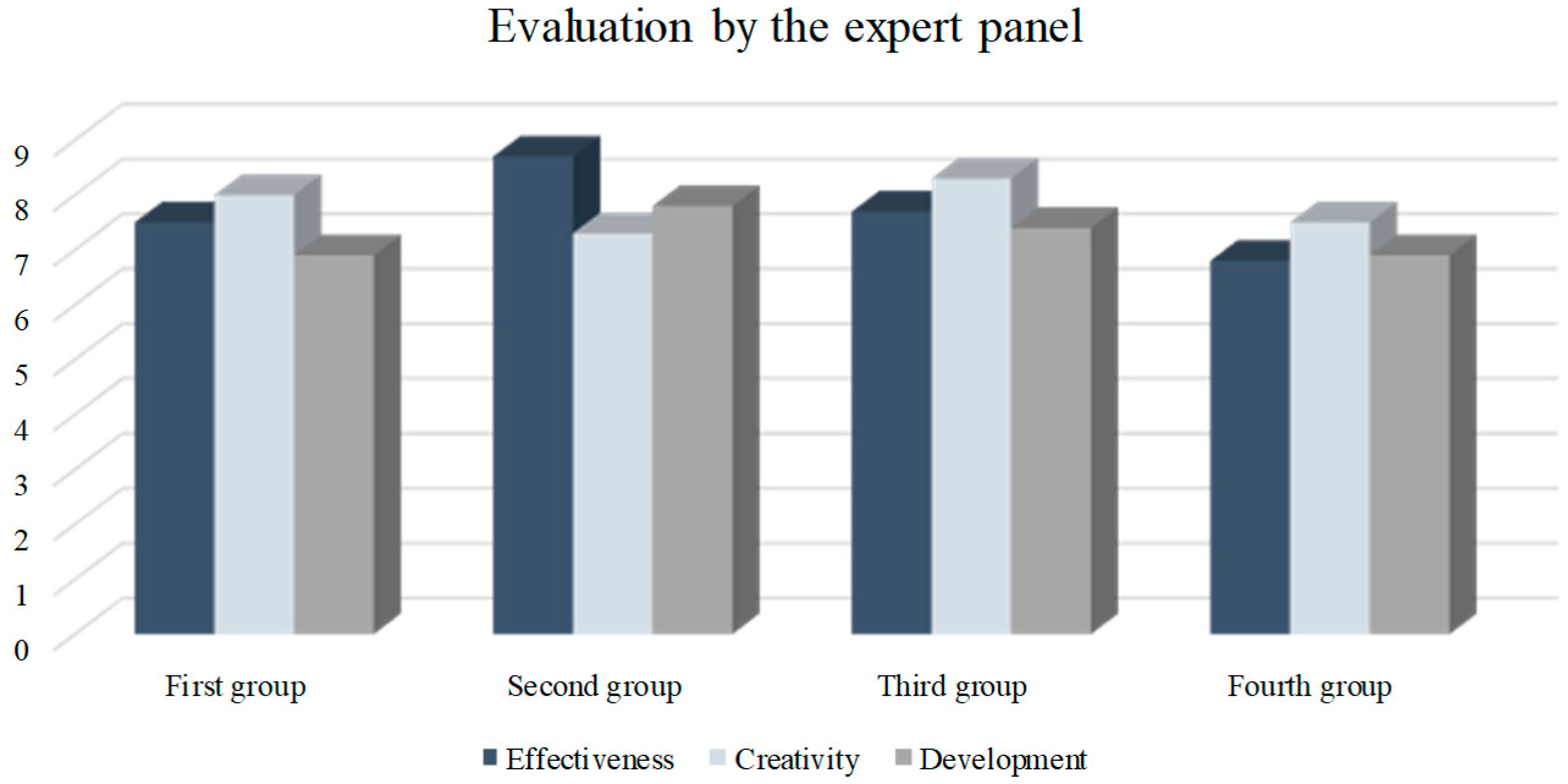

To ensure a more objective evaluation of the outcomes associated with the implementation of information exchange methods, a decision was made to assess the students’ knowledge through testing. A critical situation that could arise with the development of their businesses was chosen, and each student was instructed to come up with ways out of it. The students’ answers were evaluated by a panel that included:

The heads of the departments of economics, economics and international business (with advanced study of Chinese), and economics and international business (with advanced study of English);

Several entrepreneurs who acted as consultants and facilitators of master classes for the second and fourth groups of students during the experiment.

Students were graded on a ten-point scale in three categories: solution effectiveness, creativity, and development opportunities (see

Figure 4).

According to the evaluation by the expert panel, the students’ knowledge after the experiment improved the most in the second group, for which training was based on the European methodology. They demonstrated a good understanding of problem-solving, with an average score of 8.7 out of 10 points for all students and an average of 7.8 out of 10 points for development opportunities. Their creativity remained essentially the same as that of the other students, with a score of 7.3. The highest creativity was demonstrated by the students who were taught the Korean methods—they were rated 8.3 out of 10 points. They showed good problem-solving skills, with a score of 7.7 out of 10 points, and skills to build development schemes, with a score of 7.4 out of 10 points. Students in the first group demonstrated improved performance on approximately all criteria. The expert panel gave 7.5 points for their ability to solve problems effectively, 8 points for creativity, and 6.9 points for development skills. Although students of the fourth group, where no teaching methods were added, showed good knowledge (6.8 points for effectiveness, 7.5 points for creativity, and 5 points for development), they still lagged behind groups in which the methods adopted in other countries were used.

3.6. Fourth Phase

The responses related to the category of business creation were particularly interesting. One of the respondents from the experimental group stated that “he had never wanted to have his own business before, but now he will seriously consider it”. Additionally, students in this category provided various motivations for starting a business, such as “contributing to society by creating a useful product”. In contrast, students from the control group expressed a desire to start their own businesses based on financial incentives, stating, “I want a business to achieve financial stability”.

Similar studies in the United States, Europe, and South Korea were analyzed for comparison purposes.

Critical and creative thinking methods were used in the United States. They were only able to show their effectiveness if students were sufficiently engaged. The U.S. researchers relied on the methods of building students’ skills and personal development, activity, and engagement as the basis of their research. The following methods of improving learning effectiveness through information exchange were used: introduction of additional classes, student involvement in the learning process, and joint research with students from other universities. U.S. scholars emphasize the importance of various activities in enhancing entrepreneurial competence, specifically the sharing of knowledge. U.S. universities rely on a combination of prior theoretical knowledge and personal experience. The quality of learning is based on human psychology (

Hytti et al. 2010).

During the U.S. study, three methods were used to collect data. As in this study, students were surveyed on their level and quality of motivation, as well as their academic interest in learning and improving entrepreneurial competence. For the next phase, tests were developed from several typical questions. Two groups were involved in the study—an experimental and a control group (

Anwer 2019).

The research findings suggested that the experimental group members were more satisfied with their learning than the control group students. Collaboration with students from other universities, an independent design of classes, and participation in events led to more involvement in the process than the usual lectures. Accordingly, learning became more effective, and the quality of students’ knowledge improved (

Yusuf 2008).

Schmitz et al. (

2017) observed a noticeable rise in motivation and engagement in the educational process.

European studies were conducted at several universities in five countries: France (2 universities), the United Kingdom (1 university), Spain (2 universities), Austria (2 universities), and Poland (1 university). The research involved students of different majors and study years. The main criterion for selection was the absence of previous experience in entrepreneurship. The methods introduced at these universities involved:

Improving the competence in and awareness of entrepreneurship;

Analysis of market opportunities;

Providing students with the knowledge they need to develop their businesses;

Improving innovation management skills.

The study was based on supplementing traditional teaching methods, such as lectures or case studies, with new practices, particularly the sharing of knowledge among students and businesses or business owners. Based on the experience gained in master classes, students tried their hands at problem-solving, conducting creative activities, and applying their skills and knowledge during the workshops (

Ghandour et al. 2021;

Ndou et al. 2019).

This study suggests that proper development of businesses and good entrepreneurial competence require not only theoretical, but also practical, knowledge gained by sharing experiences with entrepreneurs who can teach students to solve sophisticated situations while running their businesses. This would make it possible to stay close to real-world contexts and to observe the progress of building one’s own enterprises in a “natural” environment (

Fayolle 2013).

European researchers also focused on the involvement of universities in improving the entrepreneurial competence among students as the main motive and source of knowledge (

Nahm et al. 2002). Supporting students in their entrepreneurial careers was assumed to incline more students to set up their businesses. Alternatively, a negative attitude by universities was anticipated to adversely affect entrepreneurial competence. This study focuses on the transfer of knowledge and motivation from universities to students, rather than on the importance of sharing knowledge with entrepreneurs and improving competence by acquiring knowledge from experienced businessmen (

Sesen 2013).

Separate studies have highlighted the importance of the popularity of entrepreneurial careers among students. The specific feature of this opinion is that the desire to acquire and exchange new knowledge, and to improve competence, is based on motivation (

Bae et al. 2014). A critical aspect to consider is the role of universities in establishing context that significantly contributes to the cultivation of entrepreneurial ambition. This, in turn, influences motivation and subsequently fosters competence among individuals (

Zhang et al. 2014).

In South Korea, motivation was tested using a seven-point Likert scale. A total of 736 respondents participated in the study, of which 80% were male and 20% were female. The survey was conducted over a year through an online and paper survey. The utilization of the Q-Sort method facilitated a reliable estimation and validation of the findings. Its elements were subsequently sorted into structures that were disassembled by experts (

Pariseau and Kezim 2007).

The study made it clear that many students are ready to improve their entrepreneurial competence and are interested in learning. Students are willing to improve their knowledge and skills. The study indicated that a substantial proportion of students who exhibited a willingness to enhance their competencies were driven by a compelling motivational factor. These findings show that strongly motivated students are more likely to improve their competence and, accordingly, to channel their energy into this area, learn, and become effective entrepreneurs (

Lee and Wong 2007).

Korean researchers tend to emphasize the importance of role models in the development of entrepreneurial competence among students. Close contact with role models is an important factor in gaining useful information and confidence. It is efficacious in fostering the development of entrepreneurial skills and enhancing the requisite knowledge for initiating business ventures. Role models can make a significant contribution to shaping young people’s expectations of their future careers and the specific features of their entrepreneurial identities. Connections with entrepreneurs play a crucial role in building entrepreneurial competence among students. An empirical analysis suggested that role models have a significant impact on students’ development and awareness of their competence (

Zhang et al. 2014).

Entrepreneurship education plays an essential role in building entrepreneurial competence and the intention to conduct business (

Fernández-Pérez et al. 2019;

Sun et al. 2017). Its development provides students with the opportunity to choose among a variety of options for an entrepreneurial career (

Schmidt and Van der Molen 2001). This implies that the development of skills, motivation, knowledge, and competence among students to achieve meaningful results has a positive impact on business development and quality (

Sun et al. 2017).

Given present-day developments, many countries become interested in improving entrepreneurial competence. In the U.S., sharing knowledge among students and between universities is a well-established practice. These studies often focus on knowledge sharing between universities and businesses. This practice is widely adopted and aimed at fostering a strong entrepreneurial interest among students through interaction and knowledge exchanges with individuals who possess significant expertise in the field.

Given the current economic developments, researchers in the United States concur that entrepreneurial learning is a crucial practice for university students. U.S. universities are making great efforts to promote entrepreneurial education by teaching entrepreneurship and making connections with businesses (

Crawley et al. 2020).

Some case studies suggest that such learning is effective as a proactive experiential method and allows students to learn about business models, approaches, and marketing strategies. These methods prioritize the interdisciplinary approach, which is quite common in U.S. universities, and blended learning strategies. Such methods of knowledge sharing will help students to build their entrepreneurial careers later (

Schmidt et al. 2006).

On the other hand, based on the research conducted by

Badawi et al. (

2019), several competencies should not be developed for future entrepreneurs. These include training in outdated information technologies and programs, skills that contradict the values of the company or other ethical values, and others.

European studies have focused primarily on knowledge sharing among students and businesses. Universities are considered to be important areas for innovations and the sustainable development of the economy, with the case method playing a significant role. This method focuses on solving various business issues in real-world contexts, so that students learn how to discover ways out of difficult situations over the course of their studies. The effectiveness of such approaches has been demonstrated, as students trained under these methods exhibit enhanced comprehension of real-world business contexts, analytical thinking skills, and improved teamwork, as evidenced by

Garlick et al. (

2006) and

Zvonnikov and Chelyshkova (

2017).

In South Korea, researchers have not emphasized the importance of educational techniques and methods as strongly as the techniques and methods of motivating the students themselves (

Kim and Park 2018). They focus primarily on developing the willingness of university students to improve their entrepreneurial competence.

The methods used in Russian universities combine many of those that are widely used in foreign educational institutions. Similarly to European approaches, case studies are utilized as a teaching method. The main difference is that Russian society does not perceive students as a way to promote innovations, and businesses are not particularly ambitious in cooperation with universities (

Breznitz and Etzkowitz 2016). There are significant similarities between the methods used in the Russian Federation and those in South Korea: more specifically, the focus on improving the motivation and interest among students.

The methods used in the United States and Europe appear to be effective according to the evaluations by the students themselves, who rated the European method 4.4 out of 5 points and the U.S. method 3.6 out of 5 points. The expert panel also confirmed the observed improvements. The European method scored 8.7 out of 10 points, and the U.S. method scored 7.5 out of 10 points. Therefore, it makes sense to introduce such techniques in the training of economics students. For example, the information exchange not only among students or between students and instructors, but also between universities and businesses, will expand students’ understanding of the current developments on the market and prepare entrepreneurs for future challenges.

The obtained data indicate that additional stimulation of entrepreneurial abilities yields a positive effect within any experimental model. Overall, several activities have been identified that have positive expectations regarding students’ entrepreneurial competencies:

- -

Business simulations: Business simulations (often in the United States) allow students to experience the challenges and advantages of running a business;

- -

Entrepreneurship education programs (training): entrepreneurship education programs provide students with the knowledge and skills necessary for starting their own businesses;

- -

Mentoring programs: Mentoring programs connect students with experienced entrepreneurs who can provide advice and support, drawing on the influencers of their time;

- -

Competition: This approach indirectly emerges in all forms of entrepreneurial competence development, considering competitions and contests as a means of acquiring competency (

Ferreras-Garcia et al. 2021).