1. Introduction

Time orientation is generally defined as a society’s attitude towards time. Time orientation can be broadly classified into two categories: short-term and long-term orientation(

Sternad and Kennelly 2017). In the corporate world, time orientation is linked to strategic intent and the planning horizon of companies. Short-term orientation is an attitude that dominates in Western society, primarily because leaders and managers evaluate and judge based on their short-term successes.

Kaplan (

2018) argues that most managers understand the necessity of long-term orientation, but the systems that their respective organisations use only reward short-term results. One of the most common justifications for focusing on short-term goals is the extent of the challenge associated with evaluating long-term goals. This challenge can be avoided by transforming the long-term strategy into multiple short-term strategies. This transformation is complex and even impossible in some cases.

As reiterated by

Saether et al. (

2021), most of the current global problems (including, but not limited to, environmental, economic dependencies, and technological developments) cannot be solved with short-term orientation. They require long-term strategies. In the business world, product or business development regularly requires long-term planning and commitment. The business world is dynamic and it becomes increasingly competitive with every passing day, thus fuelling the culture of short-term reactive strategies (

Brigham et al. 2014). The question raised in this study concerns whether these short-term strategies are sufficient, or whether they need to be changed. This research tries to analyse the link between short-term benefits for managers and the increasing tendency to focus on short-term strategies in business.

The research objective requires a comparison of the benefits and shortcomings of short- and long-term orientation for managers in developed nations. Research objectives are essential for any research project, as they enable a focussed approach and they help to avoid scope creep. To achieve the research objectives, a set of research questions has been defined, which would act as the guiding light for the research and analysis. These research questions are:

- (1)

What are the factors that have a direct impact on short-term versus long-term orientation in organisations?

- (2)

How can a focus on long-term orientation be achieved with the current extreme short-term system?

- (3)

Does the dominant western bonus system for managers support or create a short-term focus?

- (4)

How important is the awareness and involvement of the employees in terms of achieving long-term strategic orientation?

When seeking the answers to these questions, an attempt was made to construct the essentials of a basic framework that can be adopted by organisations wishing to adopt a long-term orientation strategy. This research project, and this article plan, contributes to the field with the latest data collected from managers of three western economies. This not only proves the existence of short-term orientation in businesses, but it also highlights how businesses prioritise personal gain over company benefit.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Mixed Methods

The mixed method research approach is one in which two or more gathering tools are used simultaneously to obtain results. This research work used both quantitative and qualitative approaches to acquire the results. Questionnaires were used as part of the quantitative strand of mixed methods. At the same time, qualitative questions were added to the questionnaire in order to ascertain the ‘pulse’ at the base of the organisational pyramid. The reasoning behind using a mixed methods approach is that it allows the users to triangulate results. The survey results are then compared with the interview results of 30 open conversion interviews to ascertain the consistency and reliability of the research results.

3.2. Sample and Sampling Techniques

This research uses purposive sampling in order to understand the problem at hand. Purposive sampling is a type of sampling wherein each sample or respondent has an equal and fair chance of being chosen from the population. The selection of respondents, or sample for this research project, is chosen based on simple random sampling using NCSS Statistical Software. The respondents for this research project belong to a list of 598,876 companies that were provided by the respective chambers of commerce of Germany, the UK, and the United States. A targeted total of 100 valid respondents were received from UK companies, 100 from the United States, and 100 respondents from Germany. These companies are sector agnostic, and the list consists of companies of different sizes per their turnover. Sectors that are long-term oriented by nature (such as pharma, high-tech, etc.) were excluded.

3.3. Philosophy behind the Mixed Method Approach

The philosophical justification behind choosing a mixed methods approach is based on its ability to draw upon the benefits of both quantitative and qualitative approaches. This is central in achieving data results, as a mixed approach using quantitative and qualitative tools leads to more consistent and reliable results. Using a quantitative tool, such as a questionnaire, will allow the researcher to code the most important variables that explain the problem. Coding variables later on in the research project also enables correlations between variables to be found, thus allowing the impact of one variable on the other to be explained. The coding method is straightforward and it allows the researcher to gather results. Cross-tabulation allows the researcher to study the impact of one variable on the other and fully understand the correlations between variables. Similarly, the interview tool allows the researcher to understand the deep connotations in the minds of the respondents.

3.4. Questionnaires Approach—Rationale

Questionnaires are data-gathering tools that allow the researcher to collect data with the help of a list of questions asked by respondents. This is of central importance because questionnaires allow researchers to collect data systematically. The list of questions for respondents was pre-formulated. In some cases, critics have argued that questionnaires are a weak tool because they ignore respondents’ opinions, given that they are restricted to choosing from a list of given answers (

Cheung 2014).

There are different types of questionnaires. Close-ended questionnaires are composed of a list of questions that have a list of answers at the end; one or more answer is then chosen by the respondents. This myopic view has limited reliability as it only includes the opinion of the researchers and it does not take any input from the respondents; hence, involving respondents and their views is central to any research findings. Open-ended questionnaires only have a list of questions formulated by the researcher. The answers are not given for these questions, rather, they are left for the respondents to highlight any important variable for that question. Critics have also criticised this questionnaire type as there exists the possibility that the respondents may lose sight of what is actually being asked. This research uses semi-structured questionnaires. These questionnaire types draw on the benefits of both open-ended and close-ended questionnaires. The list of questions was distributed among respondents. The list of questions carries a choice of answers that are given at the end. Mostly, the answers were written in an objective format so that the respondents did not become demotivated and did not have to think hard. These answers were given as choices for respondents to state their answers. A Likert scale from 1–4 (with 1 as strongly agree and 4 as strongly disagree) was chosen for the respondents. The idea of using the Likert scale is to avoid the tendency of the respondents to choose the middle value, which results in spurious outcomes.

Questionnaires were distributed among 632 managers in the companies, and the responses of 300 valid questionnaires were recorded. From each company, only the leading manager (CEO, President, or General Manager) was invited to participate.

4. Results and Discussion

The current research project seeks to investigate the factors that are directly related to the selection of the short-term orientation approach within an organisation. The questions were designed in such a format so that the respondents did not need to spend too much time on them. Moreover, the responses were recorded in such a way that data entry in Excel became easier for further analysis. The survey results presented in this chapter show managers’ responses from small, medium, and large-scale organisations in three countries (Germany, the UK, and the USA). Both the qualitative and quantitative approach has been used for data analysis.

The questions were intended to record basic information about the organisation and to understand how the strategy is being implemented in the organisation. Furthermore, the data collected from the questionnaire found that multiple factors merged to contribute to the adoption of short-term orientation. Principal Component Analysis was performed to reduce these factors to limited components. Some of the key factors that emerged as part of the selection process of long-term vs short-term approaches by the managers included:

- -

Geographic location of the organisation;

- -

Age of the organisation since inception;

- -

Size of the organisation based on turnover;

- -

Performance-based approach in the organisation—annual;

- -

Orientation of managers.

Some of the factors have been introduced in the questionnaire, which we feel are important for long-term orientation selection, but understanding these factors at all levels is still a challenge for organisations; therefore, these factors are primarily included for data collection purposes. All sets of factors were subjected to a regression analysis to check if it would be possible to forecast the orientation of the organisation based on an understanding of the factors. These factors included:

- -

Adoption of long-term orientation depends on shareholders’ preferences;

- -

Emphasis on long-term strategy;

- -

Finding whose responsibility it is to implement a long-term strategic orientation;

- -

Understanding whether global issues need long-term orientation.

Once the data were collected, the results were analysed. The analysis was performed using MS Excel as a tool. The findings are as follows:

Table 1 provides a summary of the results that have been recorded as a response to questionnaires that were circulated. The responses were purely based on the understanding of the respondents and how they interpreted the questions.

4.1. Age of the Company

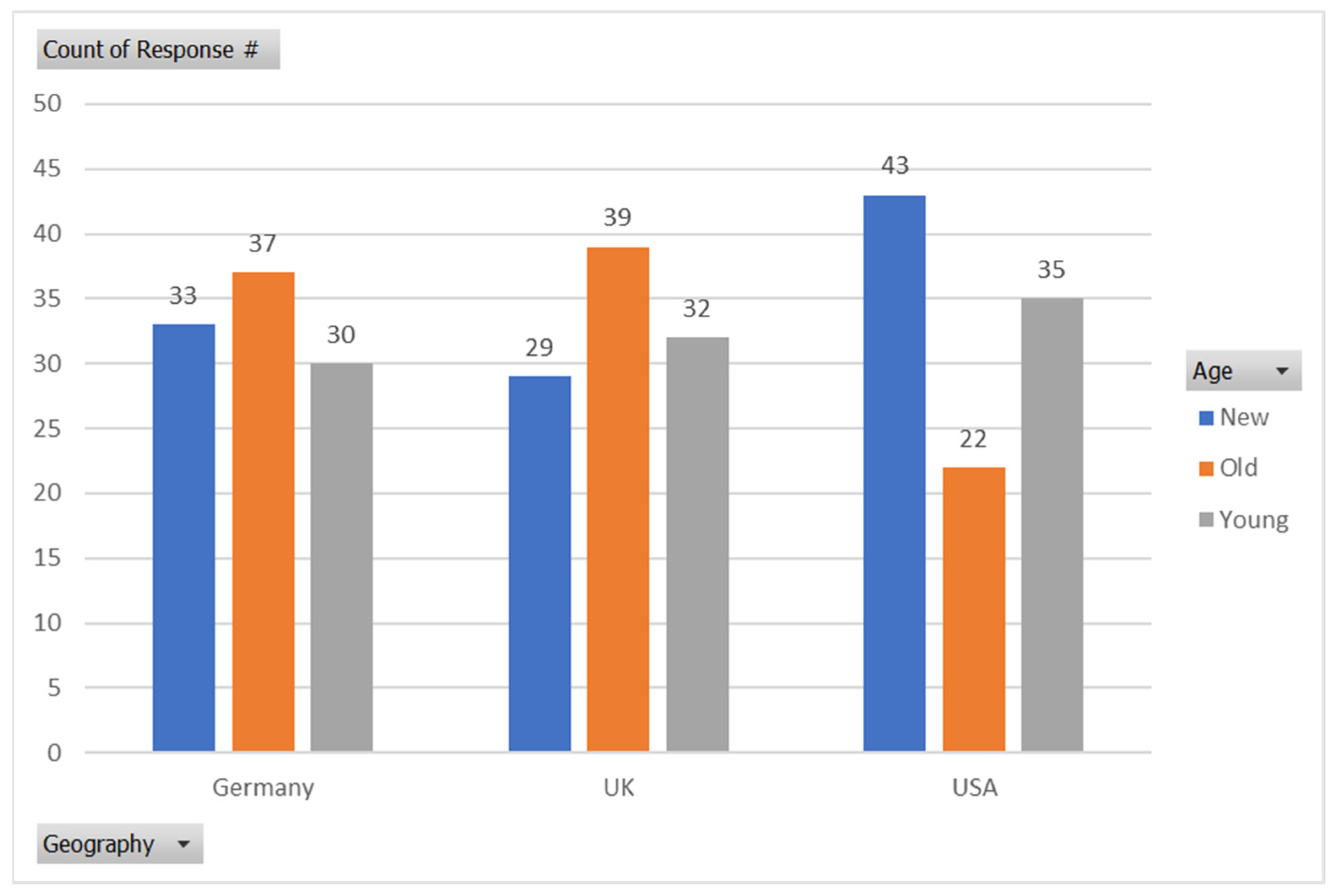

Next, we performed a similar analysis on the time from the inception date of the organisation to the current date; this was considered to be the age of the organisation. Three different age brackets have been defined: zero to five years (New), six to ten years (Young), and greater than ten years (Old). This distribution of the companies across geographies, based on age, is graphically shown in

Figure 1:

The data distribution shows that the prevalence of new companies is skewed towards the USA, whereas more old companies tend to exist in Germany and the UK. The list of young companies is almost consistent, at ~32% of the total count across geographies.

4.2. Size of the Organisation

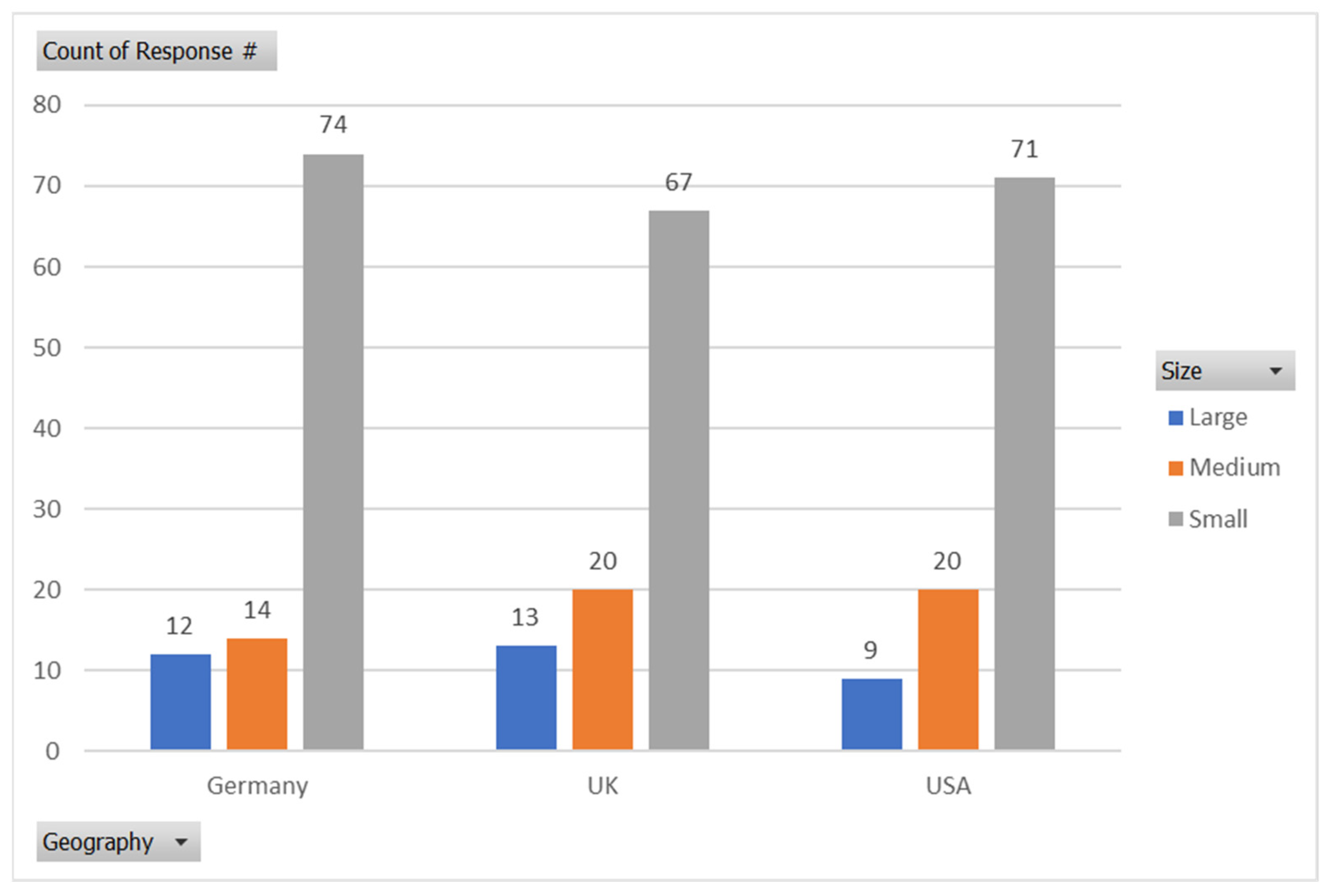

The next factor in the sequence is the turnover or size of the organisation. The size of the organisation has also been picked up as one of the factors that impacts the implementation of a long-term strategy in the organisation. Similar to the last two cases, companies have been categorised into three sizes: large, medium, and small. Large organisations have a turnover of more than USD 100 million annually; medium organisations have a turnover of USD 50–99 million annually; and small organisations do have a turnover of USD 1–49 million annually. The distribution of the companies in the sample, as per their sizes across the locations, has been shown graphically:

It can be observed from

Figure 2 that the sample size population is skewed towards small-scale companies across all locations; however, the UK has the maximum number of medium and large-scale companies.

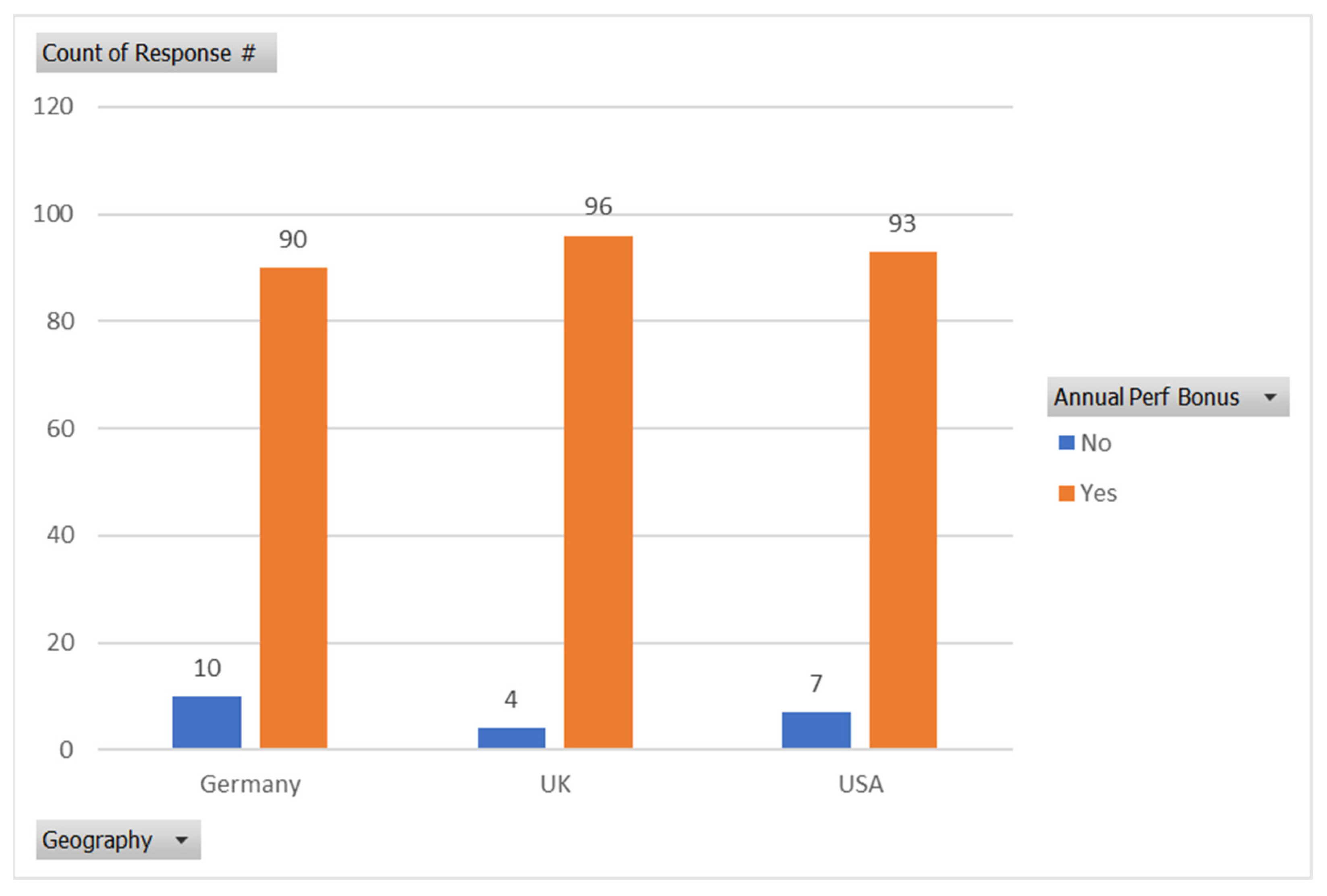

4.3. Annual Performance Bonus Policy

The next factor to be discussed is the applicability of annual performance bonuses in the organisation. As discussed in our previous section, it has been observed that organisations that have annual performance bonuses in place tend to overlook long-term strategies. From the data that we have collected and shown in

Figure 3, we found that ~93% of the total companies have an annual performance-linked bonus policy across geographies.

4.4. Orientation of Managers around LTO

In the literature review section, we noted that managers need to move towards long-term strategic orientation; this is because they mediate the gap between strategy formulation and execution. When collecting data related to this factor, we aimed to understand if the orientation of managers impacts the implementation of a long-term strategy in the organisation. The distribution of managers having long-term strategic intent is given in

Figure 4:

As is evident in

Figure 4, more than 70% of managers/companies do not have an emphasis on long-term strategy. This is main objective of our research—to delve deeper into the reasons why managers do not emphasize long-term orientation strategies.

4.5. Awareness and Record-Keeping Factors

Several questions were asked to understand the reasons behind the lack of emphasis on long-term orientation strategies. A 4-point Likert scale questionnaire was circulated among managers to capture their input on various factors that could lead to emphasis on short term orientation within the organization.

4.6. Shareholders’ Preferences and Expectations

Another factor that can influence the adoption of a strategy is the preference of the shareholders. The shareholders might be short-term oriented and they may demand a direct dividend on an annual basis. Alternatively, the shareholders might be patient, and they might have faith that the management are ready to create wealth by investing in an organisation on a long-term basis. In such a case, the profits of an organisation are reinvested for expansion and growth purposes. As the recording of these data was based on responses from the business manager population, there might be a difference in terms of what was recorded and what actually happens. This is why this particular factor has been assessed, to check the understanding level, awareness, and knowledge of the respondents.

4.7. Management Focus on Short Term Orientation Only

In an attempt to suggest frameworks for the organisation, to help them shift from a short-term orientation to a long-term orientation strategy, the baseline data must be formed in accordance with the inclinations of employees. This particular factor, of taking the viewpoints of employees into account, has been included in this study. The employees were asked to confirm whose responsibility is to implement a long-term oriented strategy. Generally, strategies tend to be formulated at the top, and then they percolate down towards the bottom of the pyramid; however, it is very important that every individual is held responsible and accountable for the implementation of the strategy, and that they follow the same strategy. Therefore, this question has been asked to collect baseline data concerning the implementation date of the strategy. The question clearly asks if management takes responsibility for long-term strategy implementation or not, and if management is focusing only on short term strategies.

4.8. Bonus Linked to Short Term Strategy

This is the most common underlying reason for managers to resort to short-term orientation. They claim that since their annual bonus is linked to short term plans and their performance on those plans, they do not feel motivated enough to adopt and practice long-term strategic intent.

4.9. Ease of Implementation

Managers often claim that short term strategies are more objective and can be measured in real time; thus, they are easy to implement and follow. This factor can be a significant motivator for managers, enabling them to rely and practice short term strategies.

4.10. Dynamic Business Environment

We are living in a continuously changing business environment. The business landscape is rapidly changing, and thus, thinking and strategizing for the long-term seems useless. This view has been appropriately supported by the recent COVID-19 pandemic, wherein great swathes of business activity came to a complete halt for more than a year (may be a greater period of time in other locations). Such a scenario is not predictable at all; therefore, managers feel that relying on short term strategies allows them to be agile and flexible when there are swift changes in the business environment. Therefore, managers feel that the benefits of short-term orientation strategies outweigh any benefits that may be obtained through long-term orientation strategies. This factor can be an important contributor towards the intent of managers to adopt short-term over long-term orientation strategies.

4.11. Self-Centered Approach of Personal Growth

There has been a culture wherein performance bonuses are given annually, and these bonuses are linked to the performance of the individual over the year. The managers are not married to the companies, and therefore, they only take a short-term, self-centered view of the strategic growth of the organization. The argument behind short term orientation is that the bonuses, promotions, and target achievements of the managers are recorded on a short-term basis, which, regarding the short-term orientation approach, helps them obtain maximum benefits.

4.12. Sustainability—Importance of Long-Term Orientation

As the name suggests, sustainability concerns maintaining the desired state for a longer period of time. Sustainability is often used as a synonym for long-term orientation; therefore, it becomes imperative to check the understanding of the relationship between sustainability and long-term orientation strategies in an organisation. Once again, the responses are based on the understanding of individuals, and this understanding can be used to define the future strategies within the organisation. If we replace sustainability with a long-term orientation strategy, as was evident from our literature review, both are compatible with one another.

Once all the factors were explained, the individual responses were recorded on a 4-point Likert scale, wherein 1 is strongly agree and 4 is strongly disagree. The descriptive analysis of the responses to the factors impacting short term orientation is given in

Table 2:

Any mean value less than two shows agreement among the respondents, and any value greater than two represents disagreement among the respondents. The highest value was obtained for ‘Shareholders’ Preference’, which means that the shareholders do not agree on the issue of reinvesting dividends for the growth of the organization; this is a long-term strategy. Rather, they believe in realizing short-term profits, which are primarily taken in the form of dividends. This also can be linked to dynamism in business. The dynamic business environment can be further extrapolated and applied to uncertainty in business. Investors therefore tend to prioritize realizing profits rather than consider long-term prospects. Such an approach from the investors is detrimental to the long-term prospects of the company, as the reinvestment of dividends is the cheapest funding option available to the companies. In case the shareholders demand high dividends, the management will be forced to either curtail the capital expenses or to look for external options for capital funding.

From the managers’ standpoint, they are inclined to adopt short term strategies because their bonuses are clearly linked to short term strategies. This is evident from the mean value of responses to this issue, which is 2.440. Moreover, it is worth noting that the standard deviation of these responses is very high, at 1.05; therefore, there are significant differences in the responses received. Such a deviation allows us to capture underlying emotions, as indicated by the fact that the respondents chose either disagree and strongly disagree as their main choice. As the annual bonus is linked with annual performance and short-term strategy, the managers are inclined to adopt a myopic short-term approach to their company’s strategy. They are likely to always be keen to have short term goals, as it tends to lead to monetary gains for employees in the form of better annual bonuses. In sum, if both managers, as well as investors, are keen to obtain financial benefits from the company, short-term strategies will always prevail over long-term interests.

A similar issue may be seen with regard to the ‘Ease of Managing’ and Dynamic Business Environment’ factors. The management emphasizes long-term strategies here, and this is evident from the responses received from the managers; however, when it comes to the actual execution of a strategy, little action occurs. Therefore, it would be fair to infer that management talks about the long-term strategy but it fails to execute a strategy and align employee welfare with long-term orientation strategies.

Each variable in the equation represents a direction or dimension. In the above table, we have analyzed seven underlying factors; this means if we make a predictive model using these seven variables, it will be a seven-dimensional equation. However, seven variables are difficult to model and are parametrically cumbersome to handle; thus, it would be beneficial to reduce the dimensions of the model while maintaining the essence of it. For such purposes, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was used. It is a factor reduction technique that allows one to reduce the dimensions of an equation or model.

This technique is based on calculating the eigen values and eigen matrices of the correlation and covariance of the factors. The first step is to find the covariance and then correlation. Both the calculations are tabulated in

Table 3:

4.13. Correlation Analysis

Once all these factors have been investigated individually, the next step is to check the result when all the factors work at the same time in order to establish the interrelationship between these factors, and to find out how these factors will behave when a long-term strategy is implemented in an organisation.

Table 4 shows the resulting correlation matrix:

When analyzing the correlation matrix, it was found that the factors were significantly less correlated with each other. The maximum magnitude of correlation was 0.07 on the positive side and 0.14 on the negative side. Both the values are very low; therefore, eliminating or combining the factors using the correlation matrix was not possible, and thus, we resorted to using the PCA technique in which the eigen matrix was calculated for all the factors, along with their contribution to the model.

Once the eigen values and eigen matrix were calculated using MS Excel (using the addin tool), the eigen values for each factor were calculated. These eigen values are given below. If we assume a standard deviation of one, the sum of all the eigen values is seven. The cumulative sum of the components is also seven, and the percentage contribution for explaining the factors is given in

Table 5:

As is evident, the maximum eigen value of factor one is 1.265, and it contributes to 18% of the explanation of the factors. Similarly, the contribution of all the factors is given. The PC4, or the fourth factor, is highlighted because until this point, 63% of the results could be explained; thus, we have chosen the top four factors and reduced the dimensionality of the model by three factors. If we look at the relationships between our seven initial factors with four components, we obtain the following observations. The resulting factor distribution is shown in

Table 6:

The highlighted cells are ones that have values above the threshold for each component. The factors ‘Ease’, Personal Growth’, and ‘Dynamic Business Environment’ can be related to PC1. The factors ‘Emphasis on LTO’ and ‘Shareholders Preference’ can be related to PC2, and so on. It is worth noting that ‘Emphasis on LTO’ has a negative contribution to PC2 because there is little emphasis on LTO and the consensus strongly disagrees with this. This is also the case with the factor ‘Bonus linked to LTS’. This factor also contributes negatively to PC3. Moreover, if one wants to understand the factors of short-term orientation and the impact this has on the company, the four factors which have been explained above would be sufficient to explain 63% of the relationship. These results are based on the overall understanding of the responses of the respondents to the questionnaire. These results might change with a change in sample size and a change in geographic composition.

Standalone analysis of the results gathered from the questionnaire responses clearly state that the managers are very selfish in their approach. Their personal gain is more important to them than company growth. This is the reason that managers always look forward to planning, executing, and achieving short term goals. Although they agree that long-term initiatives and long-term targets are important for the company, the monetary gains in the form of annual performance bonuses are linked to short term target achievement, and thus, they all tend to think and act on short term orientation strategies. This inference is in line with the studies performed by

Kaplan (

2018). Similarly, shareholders also want to achieve profits over a short period of time. This can be attributed to uncertain business environments, the cyclicality of the asset classes, geopolitical tensions, and the overall investment behavior of the stakeholders.

5. Conclusions

It is evident from the literature analysis of different viewpoints (sociology, finance, organizational strategy, and sustainability), as well as empirical research, that companies which are large, settled, and located in the western world are inclined to plan for long-term oriented strategies. The managers and employees understand the benefits of long-term orientation, and they are willing to work on long-term growth and a sustainable business model for the company. Several other factors have also been discussed as a part of this research, which requires work from the senior management of the organization to create a culture, motivate the managers, and convince the shareholders to develop a mindset wherein long-term orientation strategies are prioritized. The challenges that managers face are changing rapidly; therefore, adopting a long-term perspective is needed, along with a prevalent short-term tactical view. A culture that values preserving money has enough money to make long-term investments; therefore, having patience is the key for many cultures (

Wang et al. 2015). As only 34% of the shareholders in our study seem to not to follow this logic, and still prefer short-term benefits over potentially higher long-term returns, the role of top mangers becomes even more important with regard to the future implementation of LTO. Similarly, employee contributions do not synergize, nor do they achieve any results for the company; it is associated with loss and shame, which has become the driving force for workers. Research conducted by Hofstede argues that since different cultures have different time orientations, most western countries, such as America, choose a short-term orientation strategy for their business. Conversely, countries such as Thailand choose long-term orientation, as it is argued that their cultures prefer long-term orientation (

Bruce and Taylor 1991). It has therefore been stressed that managers that belong to countries that value long-term orientation strategies have a completely futuristic view of their strategies. This is also an important factor to consider because businesses must expect to bear the results in the long run only, and hence, short-term is considered myopic (

Wang et al. 2015). Additionally, it is worth mentioning that these managers need to have a great deal of patience in order to let go of any short-term benefits and to ensure that long-term goals are achieved robustly. With regard to the example of the US, the managerial stance is skewed towards the short-term. Only 27% of all American respondents expressed a preference towards LTO. It is important to note that American culture divides its time into several categories by adopting strategies, such as meeting deadlines and making schedules (

Wang et al. 2015). The discourse that centers around the field of business and finance argue that adopting short-term orientation strategies by business managers is considered to be myopic (

Brigham et al. 2014); therefore, managers must consider long-term strategies to maximize the value for shareholders and stakeholders. The results of the interviews also indicate that professionally, managers do prefer long-term strategies but prioritize short-term strategies that lead to annual bonus payments. Indeed, 87% (261 out of 300) of the participants confirmed that LTO strategies would benefit the business; nevertheless, 88% of the respondents still prioritize personal gain over company benefit. This is a serious argument which must lead to an overall review of existing performance evaluation systems that involve bonuses.

As more companies commit to the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), long-term orientation becomes more of a focus. Companies that wish to adopt a framework for a long-term strategic orientation need to start with the basics; for instance, creating awareness about the benefits of long-term orientation. The learning and development teams, in partnership with the HR teams of these companies, need to plan a series of training modules, and an on-the-job learning environment should be created to provide employees with a common understanding of the concept and benefits of LTO. Furthermore, managers need to play a stronger and more transparent role in communicating messages from senior management to employees, with regard to strategies and their implications. This process is not an overnight affair, but adherence to LTO will require businesses to imbibe the implications and its benefits of long-term orientation as a part of its culture. Additionally, the existing performance evaluation systems that include bonuses need to be revised to better support long-term goals; therefore, to summarize, a new framework should be focused on LTO by supporting the managers’ intent, convincing the shareholders of a long-term view, and creating an overall long-term strategic culture in the organization. Each individual in the organization needs to feel a degree of responsibility and accountability so that the long-term objectives are adhered to, which should its success. Only then will organizations be able to build a sustainable business model for themselves, society, and the global marketplace at large.